Using Writing to Enhance Learning in Religious Education: Practical Ideas for Classroom Use

Dennis A. Wright

Dennis A. Wright, “Using Writing to Enhance Learning in Religious Education: Practical Ideas for Classroom Use,” Religious Educator 3, no. 3 (2002): 115–121.

Dennis A. Wright was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this was published.

[1] Writing is essential to the kingdom of God. Adam and Eve kept a book of remembrance and taught their children to read and write (see Moses 6:5–6). Prophets and others called of God recorded the prophecies and histories of their peoples. The Nephites wrote to persuade their children and brethren to believe in Christ (2 Nephi 25:23). They kept the commandment “that all men . . . shall write the words which [the Lord spoke] unto them” (2 Nephi 29:11). Peter, Paul, and John wrote epistles expounding doctrine and strengthening the Saints. Joseph Smith wrote his prayers, recorded his visions, and sent letters of comfort to the Saints. The Lord esteems the writings of His servants so highly that He has declared He will judge the whole world from their books (see 3 Nephi 27:25–26).

But all the books have not been written. As students and teachers of the gospel, we have our own opportunity to write the words that God speaks to us. This invitation is extended to all the Saints, not just the prophets. Paul taught, “He that prophesieth speaketh unto men to edification, and exhortation and comfort” (1 Corinthians 14:3). As a church, we seek to edify others through our sacrament talks, via the lessons we teach, and in our missionary efforts. The process of thinking and writing enhances the service we offer. When we help our students learn how to ponder the gospel of Jesus Christ through classroom and personal writings, we teach students to act upon an important principle of edification. When we encourage students to communicate their faith through writing as well as through speaking, we provide an important opportunity for the Spirit to witness the truth.

As religious educators, we have a unique responsibility to help our students explore the gospel through their writing and thus improve their ability to communicate its truths with others. The act of writing encourages thinking and pondering, which enhances communication skills. Writing, as a learning vehicle, enables students to probe more deeply the wonders of God’s word. Through writing, students can clarify their thoughts and feelings and enhance their learning.

Religious educators have enough to teach without supplementing their curriculum with writing classes. That is why I have been careful to suggest activities that have an immediate classroom application. This article offers helpful tools to encourage student writing. It presents a variety of teaching ideas that will help students use writing to enhance their experience in religious education. The suggestions include various types of writing activities for different experience levels and explanations of how students benefit from each activity. My objective is to provide a list of “idea starters” that can be modified according to teachers’ individual gifts as instructors and the needs of the different classes they teach. Certain ideas may complement your style of teaching; others may work for one class and not another; and some may simply be too much for you and your class. I encourage you to experiment with the activities so you can discover what works best for you.

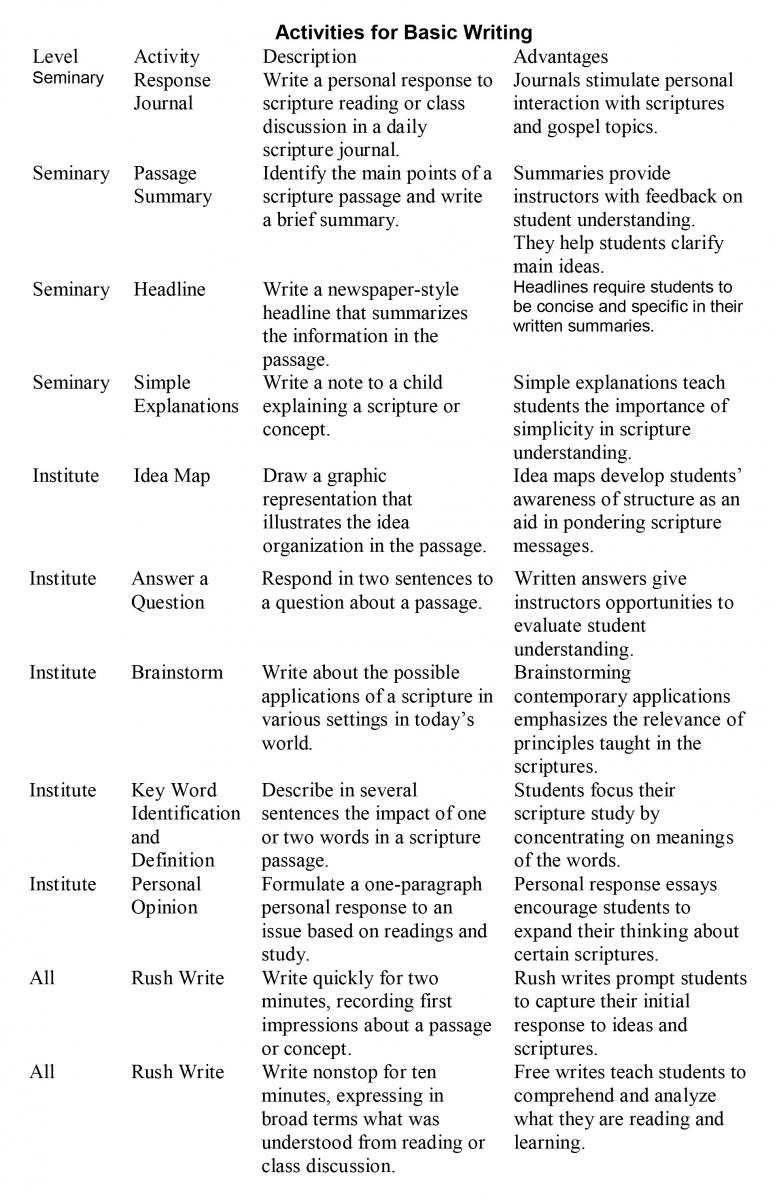

1. Ideas for Basic Writing

The activities for basic writing are simple and direct. Their purpose is to help students interact with course material through writing. They encourage students to think openly and directly about the scriptures while providing the teacher with continuous feedback concerning student progress and the effectiveness of the course. I have suggested an experience level that is best suited for each activity. However, you may find that with modification, the activities can be used at all levels.

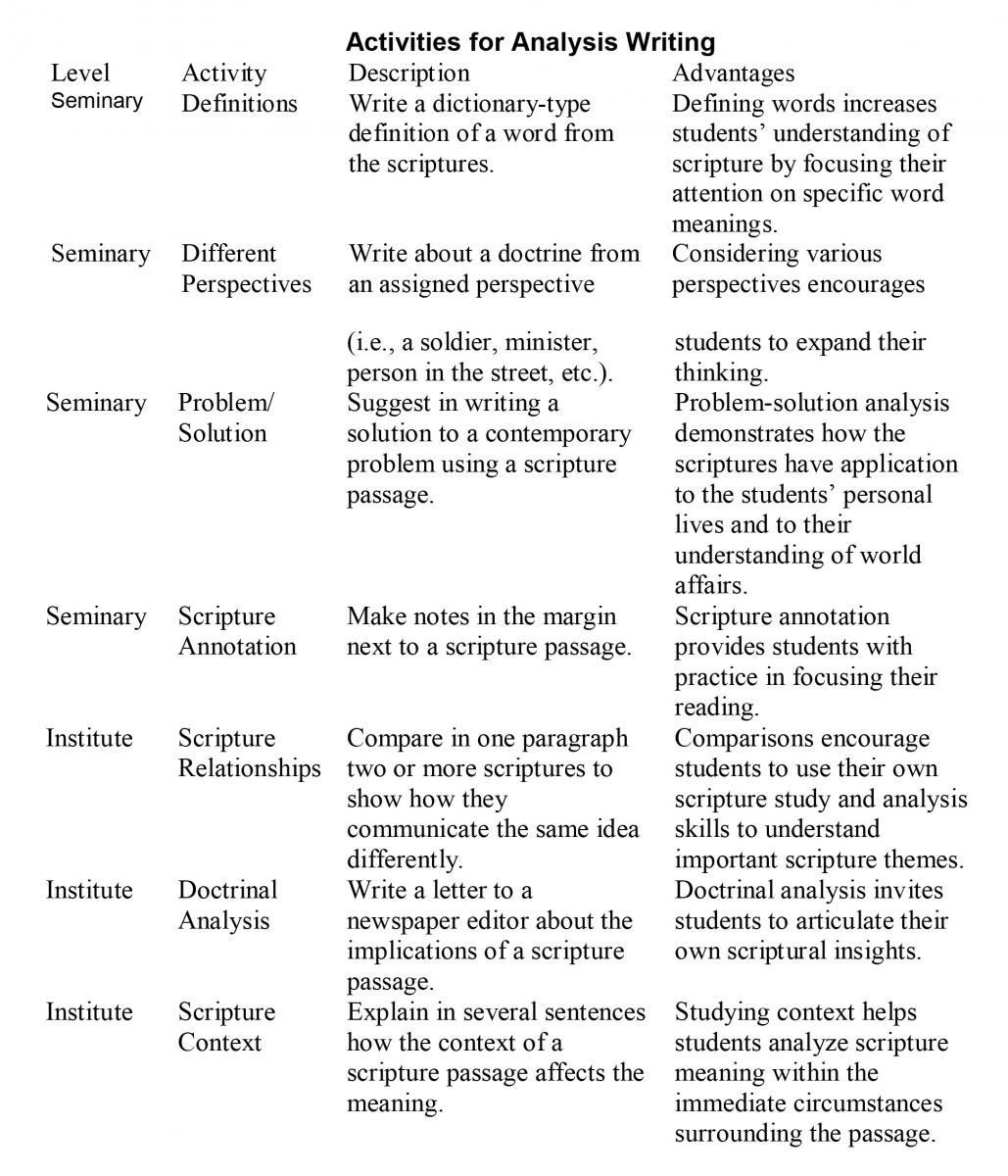

2. Ideas for Analysis Writing

Students should be invited and encouraged to use writing to specifically examine their own thoughts and insights. Analytical writing requires students to develop confidence in their skill as thinkers and writers in religion. These activities require in-class time for writing. Teachers should understand that the quiet time during which students are writing can be just as productive as the time during which the teacher is talking. Students benefit from feedback regarding their writing. By providing such help, teachers encourage students’ understanding of how writing promotes clear thinking.

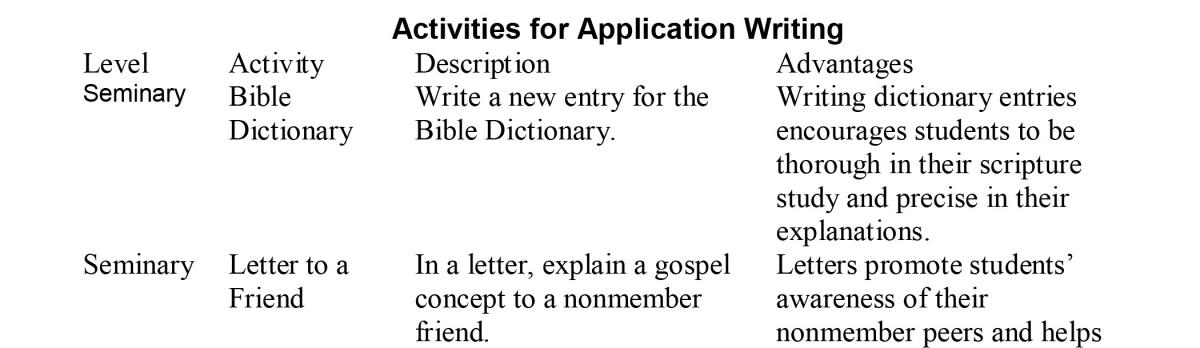

3. Ideas for Application Writing

Application writing provides students with an opportunity to write using forms common in the Church. These are similar to analysis papers except they require the student to be aware of a particular type of writing. Instructors can help students by providing models as part of the activity. One benefit of this activity is that it helps students learn how the structure of writing interacts with the content.

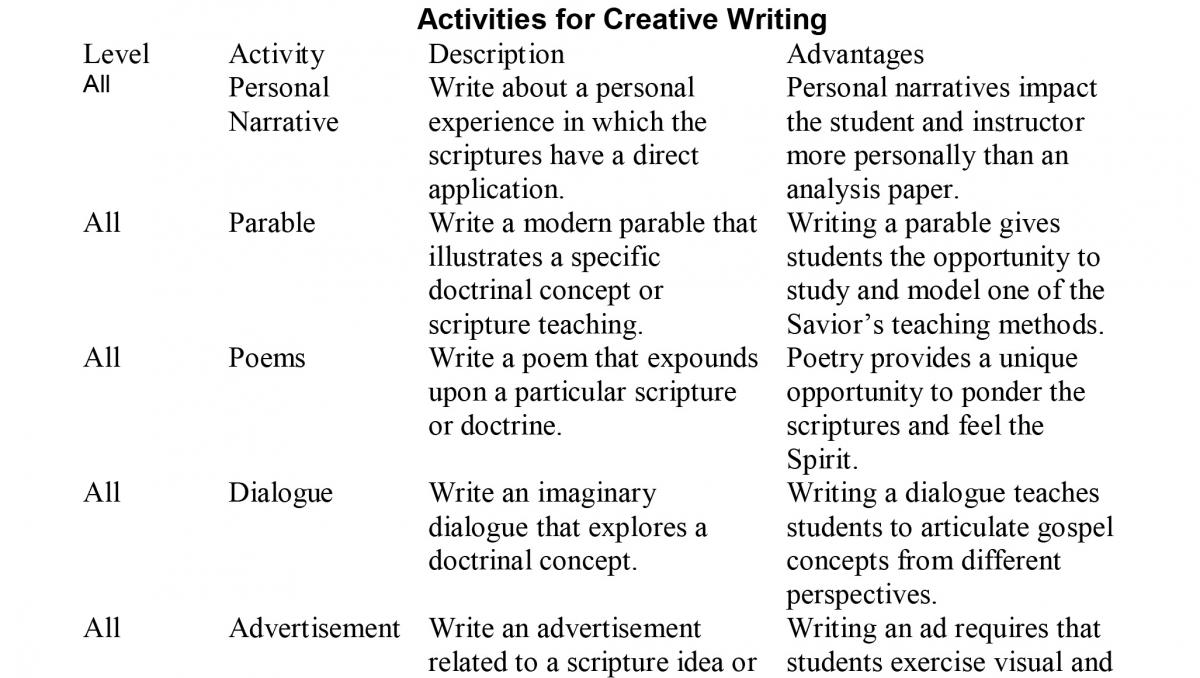

4. Ideas for Creative Writing

Creative-writing assignments are usually a welcome option for students. They provide an opportunity to explore their creative talents in relation to the scriptures. Often, these activities result in some of the most innovative insights, giving students and teachers a chance to take pleasure in the aesthetic side of religious writing. Note that the ideas below are suitable for all experience levels.

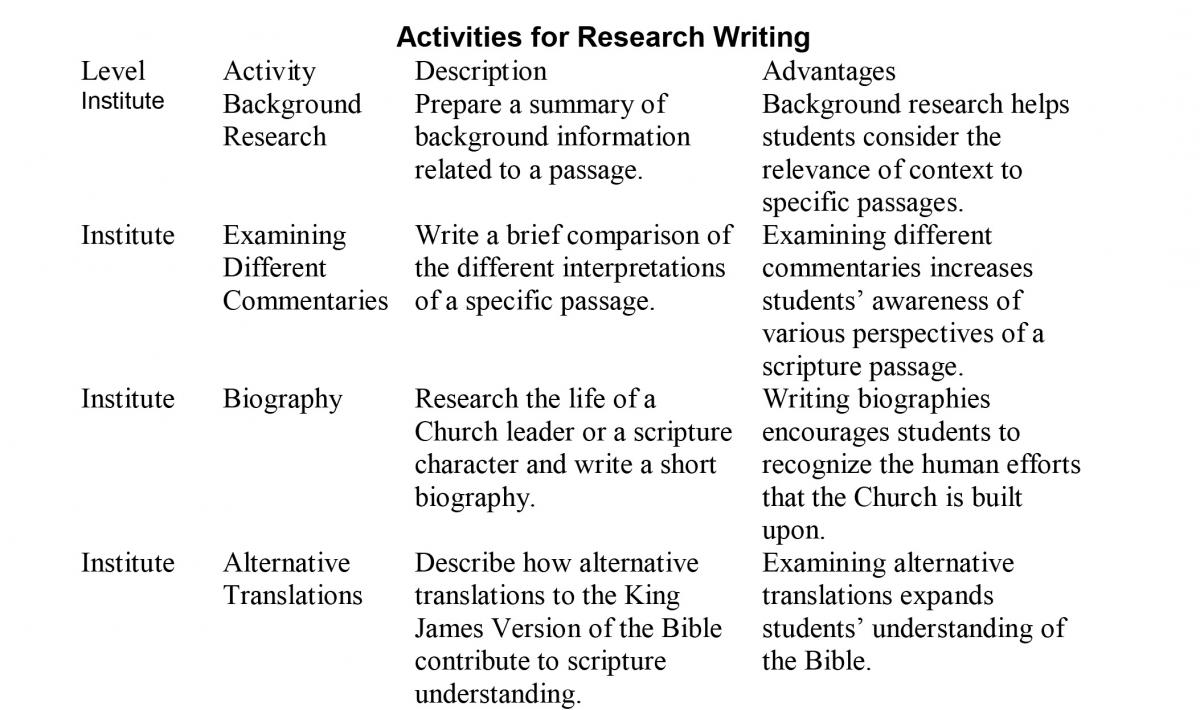

5. Ideas for Research Writing

Research writing provides an opportunity for an in-depth examination of scriptural ideas. It promotes the exploration of new thoughts through reading and pondering information from a variety of sources. Students can use research activities as a way to complement course material and take responsibility for self-directed learning. Although a formal research paper is usually not required in seminary or institute, informal research writing can enhance learning and add to class discussion. Although research activities are suggested only for the institute level, in certain circumstances, they could be adapted for seminary purposes.

Final Thoughts

Before trying any of the suggested ideas, you should determine how you want to use writing to enhance learning. You will need to consider purposefully your students and your teaching objectives. Once you have determined the role of writing in your class, carefully introduce the writing activities. Help students understand that writing magnifies learning and that it is an important part of your class. The expectations of the assignments must be clear to the students. When they see a definite starting point for the activity and a defined product expectation, they will be more likely to overcome the natural resistance that all writers face. Remember that for most students, writing in a religious education setting may seem unusual at first. Reassure them by explaining the importance of writing in the learning process. It will be helpful if you begin with small, easy writing activities to build student confidence and to demonstrate how writing will be used to facilitate classroom discussion.

Once your students start writing, remember that for writing to be meaningful, it should be read by someone. Students will write with greater interest if they know that their teacher or others will be reading what they have written. You will find that most students enjoy sharing and discussing what they have written, providing classroom discussion with more personal and specific insights. Using student writing as part of a class discussion also promotes spontaneity and variety.

As with all new things, both you and your students will experience a learning curve when you use writing activities. Your success in implementing writing will depend upon your interest and your determination to establish a new expectation in your class. You may find that in using writing as a way to enhance learning, you will have found another way to write the law upon the hearts of your students (see Hebrews 8:10). That is, after all, our prime objective as religious educators.

Notes

[1] The author wishes to acknowledge Erica Griggs and Casey Nelson, student research assistants at Brigham Young University, for their contributions to this article. This article was based on material from the Writing to Learn Guidebook published by Religious Education at Brigham Young University as part of the series Resources for Religious Educators. A bibliography of resources that support the content of this article follows:

Bizzell, Patricia and Bruce Herzberg, The Bedford Bibliography for Teachers of Writing, 4th ed. Boston: Bedford Books of St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

Connors, Robert and Cheryl Glenn, eds., The Saint Martin’s Guide to Teaching Writing, 3d ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995.

Howard, Rebecca Moore and Sandra Jamieson, The Bedford Guide to Teaching Writing in the Disciplines: An Instructor’s Desk Reference. Boston: Bedford Books of St. Martin’s Press, 1995.

Hult, Christine A., Research and Writing across the Curriculum. Boston: Allyn and Bacon: 1996.

Tate, Gary, Edward P. J. Corbett, and Nancy Myers, The Writing Teacher’s Source Book, 3d ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Trimble, John R., Writing with Style: Conversations on the Art of Writing. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1975.