“A Voice of Gladness for the Living and the Dead” (D&C 128:19)

Susan Easton Black

Susan Easton Black, “‘A Voice of Gladness for the Living and the Dead’ (D&C 128:19),” Religious Educator 3, no. 2 (2002): 137–149.

Susan Easton Black was a professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this was published.

Years before the Prophet Joseph Smith announced the doctrine of baptism for the dead, glimpses of the glorious principle were revealed to him. In 1836 in an upper room of the Kirtland Temple, the Prophet exclaimed, “I [see] Fathers Adam and Abraham, and my father and mother, [and] my brother, Alvin, that has long since slept.” In reference to Alvin, he “marveled how it was that he had obtained an inheritance in that kingdom, seeing that he had departed this life before the Lord had set His hand to gather Israel the second time, and had not been baptized for the remission of sins.” When Joseph sought clarification as to how his beloved brother could have inherited celestial glory, the voice of the Lord declared, “All who have died without a knowledge of this Gospel, who would have received it if they had been permitted to tarry, shall be heirs of the celestial kingdom of God; . . . for I, the Lord, will judge all men according to their works, according to the desires of their hearts.”[1]

In July 1838, in reply to the query, “What has become of all those who have died since the days of the apostles?” Joseph answered, “All these who have not had an opportunity of hearing the gospel, and being administered unto by an inspired man in the flesh, must have it hereafter, before they can be finally judged.”[2]

Two years passed before Joseph again spoke of the deceased hearing the gospel of Jesus Christ. The occasion was the funeral of Seymour Brunson, a high councilor and bodyguard of the Prophet. Forty-year-old Brunson died on 10 August 1840 in Joseph Smith’s home.[3] “For awhile he desired to live and help put over the work of the Lord but gave up and did not want to live,” stated his descendants. “After calling his family together, blessing them and bidding them farewell,” he succumbed.[4] Heber C. Kimball, witness to Brunson’s death, wrote to John Taylor, “Semer Bronson is gon. David Paten came after him. the R[o]om was full of Angels that came after him to waft him home.”[5]

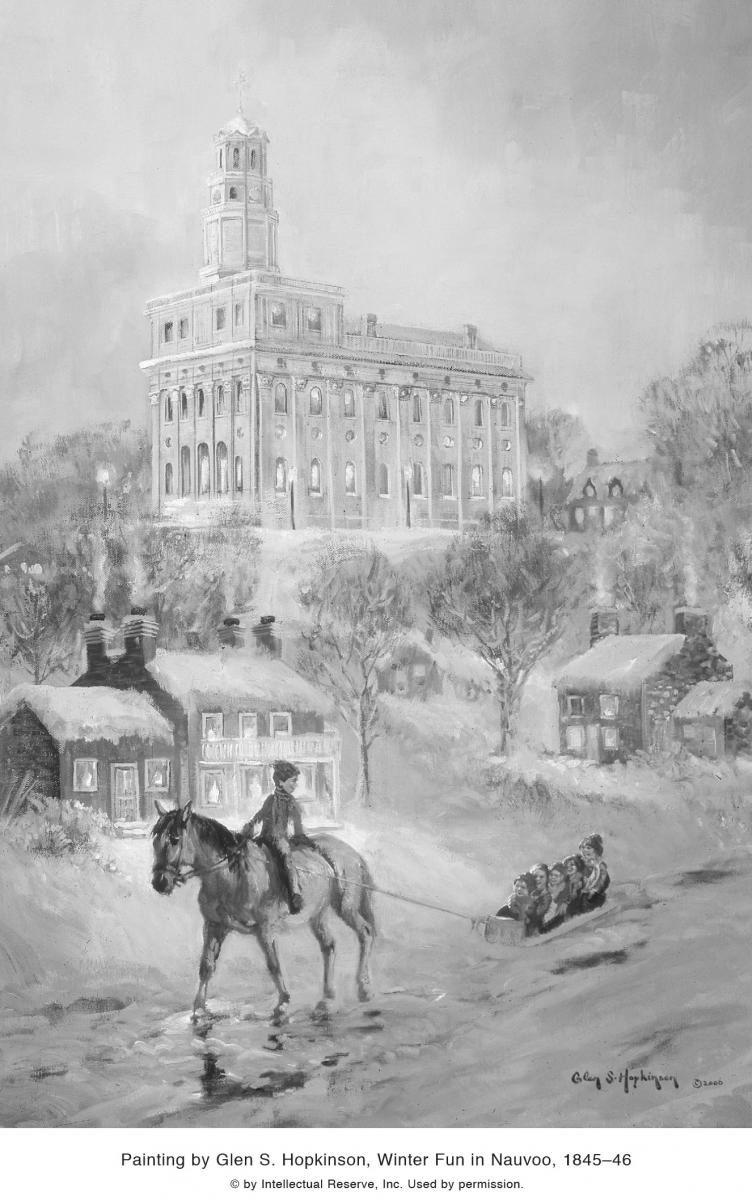

Five days after Brunson’s demise, on 15 August 1840, his funeral was held at the burial ground located on the bluff overlooking Nauvoo. According to Heber C. Kimball, the procession to the burial ground was “judged to be one mile long.”[6] Once the processional reached the site, mourners listened as the Prophet eulogized his bodyguard. Although there is no known text of his discourse, the History of the Church states: “[Seymour Brunson] has always been a lively stone in the building of God and was much respected by his friends and acquaintances. He died in the triumph of faith, and in his dying moments bore testimony to the Gospel that he had embraced.”[7]

Baptisms for the Dead

Although his statements were grand, it was the Prophet’s announcement of the doctrine of baptism for the dead that captured the imagination of the mourners. According to Simon Baker, Joseph Smith read 1 Corinthians 15 and acknowledged that the Apostle Paul was “talking to a people who understood baptism for the dead, for it was practiced among them”[8] (see John 3:5). Then, seeing among those assembled at the burial ground a widow whose son had died without baptism, the Prophet added, “This widow [had read] the sayings of Jesus ‘except a man be born of water and of the spirit he cannot enter the kingdom of heaven,’ and that ‘not one jot nor tittle of the Savior’s words should pass away, but all should be fulfilled.’” He announced that the fulfillment of the Savior’s teaching had arrived, that the Saints could now “act for their friends who had departed this life, and that the plan of salvation was calculated to save all who were willing to obey the requirements of the law of God.”[9]

Heber C. Kimball wrote of his wife’s reaction to the new doctrine: “A more joyfull Season [says] She never Saw be fore on the account of the glory that Joseph set forth.”[10] Jane Nyman, whom historians suggest was the widow Joseph saw at the funeral, did more. Following the funeral, she pleaded with Harvey Olmstead to baptize her in behalf of her deceased son, Cyrus Livingston Nyman. Her request was granted. Witnessing the first baptism for the dead in the dispensation of the fulness of times was Vienna Jacques. On horseback, she rode into the Mississippi River to hear and observe the ceremony. Although the witness, the proxy for the deceased, and the words pronounced by Harvey Olmstead are not acceptable today, Joseph Smith gave his approval of the baptismal ordinance in behalf of Cyrus Nyman.

From that time forward, Saints in Nauvoo waded knee-deep into the Mississippi River to be baptized as proxy for their deceased kindred and friends (see D&C 127; 128). And Joseph continued to receive revelations that clarified this glorious new doctrine. “The Saints have the privilege of being baptized for those of their relatives who are dead, whom they believe would have embraced the Gospel, if they had been privileged with hearing it, and who have received the Gospel in the spirit, through the instrumentality of those who have been commissioned to preach to them while in prison,” declared the Prophet.[11]

“I could lean back and listen. Ah what pleasure this gave me,” penned Wandle Mace. “[The Prophet] would unravel the scriptures and explain doctrine as no other man could. What had been mystery he made so plain it was no longer mystery. . . . I ask, who understood anything about these things until Joseph being inspired from on high touched the key and unlocked the door of these mysteries of the kingdom?”[12] Brigham Young added, “[Joseph] took heaven, figuratively speaking, and brought it down to earth; and he took the earth, brought it up, and opened up, in plainness and simplicity, the things of God.”[13]

“If the dead rise not at all, why are they then baptized for the dead?” Joseph asked his followers. “If we can, by the authority of the Priesthood of the Son of God, baptize a man in the name of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, for the remission of sins, it is just as much our privilege to act as an agent, and be baptized for the remission of sins for and in behalf of our dead kindred, who have not heard the Gospel, or the fullness of it.”[14]

Most memorable were Joseph’s words, “Brethren, shall we not go on in so great a cause? Go forward and not backward. Courage, brethren; and on, on to the victory! Let your hearts rejoice, and be exceedingly glad. Let the earth break forth into singing. Let the dead speak forth anthems of eternal praise to the King Immanuel, who hath ordained, before the world was, that which would enable us to redeem them out of their prison; for the prisoners shall go free” (D&C 128:22).

Of the Prophet’s teachings, Wilford Woodruff penned, “I remember well the first time I read the revelation given through the Prophet Joseph concerning the redemption of the dead—one of the most glorious principles I had ever become acquainted with on earth. . . . Never did I read a revelation with greater joy than I did that revelation.”[15] So welcome had been Joseph’s words that his admonition that those who neglect this great work for the dead “do it at the peril of their own salvation” was not disturbing.[16]

Baptisms in the Mississippi

Latter-day Saints from Nauvoo to Quincy, Illinois, and even as far away as Kirtland, Ohio, entered river waters to be baptized as proxy for departed loved ones. Bathsheba Smith recalled Joseph Smith “baptizing for the dead in the Mississippi River.”[17] Aroet Hale wrote, “The Prophet set the pattern for the baptism of the dead. He went into the Mississippi River and baptized over 200. Then the apostles and other elders went into the river and continues the same ordinance. Hundreds were baptized there.”[18] Wilford Woodruff wrote of that occasion, “Joseph Smith himself . . . went into the Mississippi rover one Sunday night after meeting, and baptized a hundred. I baptized another hundred. The next man, a few rods from me, baptized another hundred. We were strung up and down the Mississippi baptizing for our dead. . . . Why did we do it? Because of the feeling of joy that we had, to think that we in the flesh could stand and redeem our dead.”[19]

Among those entering baptismal waters in August 1840 was William Clayton: “I was baptized first for myself and then for my Grandfather Thomas and Grandmother Ellen Clayton, Grandmother Mary Chritebly and Aunt Elizabeth Beurwood.”[20] Although he and others would question the lack of structured organization of these first baptisms, for the practice varied up and down the river and few recorded the events of the day, joy overcame any sense of neglect to properly regulate the ordinance.[21] “We attended to this ordinance without waiting to have a proper record made,” confessed Wilford Woodruff. He lamented, “Of course, we had to do the work over again. Nevertheless, that does not say the work was not of God.”[22]

Latter-day Saints seemed to intuitively know that “the greatest responsibility in this world that God has laid upon us is to seek after our dead” and were eager to comply.[23] A flury of letters were sent from hopeful proxies to distant relatives asking for genealogical information about kindred dead. Jonah Ball wrote, “I want you to send me a list of fathers relations his parents & Uncles & their names, also Mothers. I am determined to do all I can to redeem those I am permitted to.”[24] Sally Carlisle Randall asked a relative to “write me the given names of all our connections that are dead as far back as grandfathers and grandmothers at any rate.” She then added, “I expect you will think this [baptism for the dead] is a strange doctrine but you will find it is true.”[25]

A Baptismal Font

Jonah Ball and Sally Randall knew of the important work for the dead, and they were eager to be proxies for loved ones in the Mississippi River. But it would not be long for them and others until the season of baptizing in the river ended. “God decreed before the foundation of the world that that ordinance should be administered in a font prepared for the purpose in the house of the Lord,” Joseph explained.[26] Then, on 3 October 1841, he declared, “There shall be no more baptisms for the dead, until the ordinance can be attended to in the Lord’s House.”[27] The Lord explained, “This ordinance belongeth to my house, and cannot be acceptable to me, only in the days of your poverty, wherein ye are not able to build a house unto me. . . . And after this time, your baptisms for the dead, by those who are scattered abroad, are not acceptable unto me” (D&C 124:30, 35).

After thirteen and a half months (15 August 1840 to 3 October 1841), baptisms for the dead in the river halted while William Weeks, architect of the Nauvoo Temple, prepared drawings for a baptismal font for the Nauvoo Temple. Weeks drew twelve oxen shouldering a molten sea, symbolic of the encampment of the twelve tribes encircling the tabernacle during the days of Moses.

According to the Historical Record, “President Smith approved and accepted a draft for the font made by Brother Wm. Weeks.”[28] His acceptance led Weeks to stop other architectural activities and begin carving a set of twelve oxen to support the proposed font. After laboring six days, he assigned Elijah Fordham, a convert from New York City, to complete the carving. Elijah, assisted by John Carling and others, spent eight months perfecting the oxen and the font and completing the ornamental moldings for the baptistry area of the Nauvoo Temple.[29]

When their work was finished, Joseph Smith wrote a detailed description of the font:

The baptismal font is situated in the center of the basement room, under the main hall of the Temple; it is constructed of pine timber, and put together of staves tongued and grooved, oval shaped, sixteen feet long east and west, and twelve feet wide, seven feet high from the foundation, the basin four feet deep, the moulding of the cap and base are formed of beautiful carved wood in antique style. The sides are finished with panel work. A flight of stairs in the north and south sides lead up and down into the basin, guarded by side railing.

The font stands upon twelve oxen, four on each side, and two at each end, their heads, shoulders, and fore legs projecting out from under the font; they are carved out of pine plank, glued together, and copied after the most beautiful five-year-old steer that could be found in the country, and they are an excellent striking likeness of the original; the horns were formed after the most perfect horn that could be procured.[30]

The font attracted the attention of newspaper reporters from Missouri to New York. A correspondent from the St. Louis Gazette wrote that “the idea of this font seems to have been revealed to the prophet, directly by the plan of the molten sea of Solomon’s temple.”[31] A writer for the New York Spectator announced, “In the basement is the font of batisms, . . . one of the most striking artificial curiosities in this country.”[32] Graham’s American Monthly Magazine published an engraving of the Nauvoo Temple, depicting the font outside the temple “so that it could be seen” by its readers.[33]

It wasn’t just reporters who were attentive to the font. Visitors to Nauvoo often gazed upon the molten sea and the temple walls. Emily Austin wrote that “acquaintances and strangers . . . were almost constantly coming to see” the font and the rising temple walls.[34] Some of the visitors mused that the font was the eighth wonder of the world.[35] Reverend Moore wrote, “The basement of this temple is laid—and in the basement is the baptismal font, supported by 12 oxen. In this I learned that persons are baptized for the dead, and for restoration to health.”[36]

Acknowledging the many curious speculations about the font, Joseph Smith stated to Brigham Young, “This fount has caused the Gentile world to wonder.”[37] Yet, for little children, the font was not a wonder but was wonderful. “The Prophet Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum lifted my sister Cynthia and myself up on the oxen which held up the fount, this pleased us very much and we thought it the most wonderful place we had ever seen,” recalled Abigail Morman.[38] But for adult members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, adulations were subdued, for they were inclined to speak in reverent whispers of the opportunities that awaited them in continuing their work of baptism for kindred dead. They knew that the wooden font was in its place on Temple Hill, water for the font was channeled from a nearby well, and the temporary frame walls and a roof were protecting the structure from gaping eyes. To them it was time again to resume their important work.

Baptisms in the Temple

On 8 November 1841, the baptismal font was dedicated by the Prophet Joseph Smith. Two weeks after the dedication, baptisms were performed in the font on Sunday, 21 November 1841. Acting as officiators on that date were Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and John Taylor. They baptized about forty persons in the presence of the Twelve, who had assembled to witness the ordinances.[39] Reuben McBride was the first of the forty baptized that day. He was followed by Samuel Rolfe. Joseph instructed Rolfe to wash in the font and promised him that if he would do so, his hand, which had been seriously afflicted, would be healed. Rolfe followed the Prophet’s admonition and dipped his hand in the font, and within a week his hand had healed.[40]

The blessing of healing in baptismal waters was to be repeated again and again in the wooden font, as was the baptismal ordinances for kindred dead. Joseph Hovey recalled one such incident: “I, Joseph, did prosper well in good health but my wife, Martha, was not so well as myself. . . . She was very low. But she was healed by going to the baptismal font and was immersed for her health and baptized for her dead.”[41] That the Nauvoo Temple font was “for the baptism of the living, for health, for remission of sin, and for the salvation of the dead” was well known and accepted by the Saints. That the font was in continual use in 1841 is clear. Historian M. Guy Bishop counted 6,818 baptismal ordinances completed in the river and the wooden font in 1841 (see table below).[42]

|

Nauvoo Baptisms for the Dead, 1841 |

||

|

Sex of Proxy |

Number |

Percentage |

|

Male |

3,715 |

54.48 |

|

Female |

3,027 |

44.39 |

|

Undetermined |

76 |

1.11 |

|

Total |

6,818 |

|

|

Baptisms for the Opposite Sex |

2,937 |

43.10 |

|

Relationship of Deceased to Proxy |

Number |

Percentage |

|

Uncle/ |

1,667 |

24.45 |

|

Grandparent |

1,580 |

23.17 |

|

Parent |

1,015 |

14.89 |

|

Sibling |

969 |

14.21 |

|

Cousin |

714 |

10.47 |

|

In-law |

251 |

3.68 |

|

Friend |

203 |

2.98 |

|

Spouse |

116 |

1.70 |

|

Child |

106 |

1.56 |

|

Niece/ |

92 |

0.35 |

|

Grandchild |

16 |

0.23 |

|

Undetermined |

89 |

1.31 |

|

Total |

6,818 |

|

The Need for Order

As shown in these statistics, a major religious activity in 1841 in Nauvoo was serving as proxies for kindred dead. However, the religious activity is greater than noted. The statistics do not reflect those who were baptized for the dead but failed to have their proxy work recorded. In their enthusiasm to complete the ordinances, they failed to heed the Lord’s directive, “Let all the records be had in order, that they may be put in the archives of my holy temple, to be held in remembrance from generation to generation, saith the Lord of Hosts” (D&C 127:9). The Prophet admonished the Saints: “All persons baptized for the dead must have a recorder present, that he may be an eyewitness to record and testify of the truth and validity of his record. It will be necessary, in the Grand Council, that these things be testified to by competent witnesses. Therefore let the recording and witnessing of baptisms for the dead be carefully attended to from this time forth. If there is any lack, it may be at the expense of our friends; they may not come forth.”[43]

Even after this injunction, problems of recording baptismal work were still apparent. The wooden font on Temple Hill was in such demand that adult converts and children who had reached the age of eight years sought other locations in which to continue their baptismal work. They rationalized that the crowded font and the possibility of interfering with the manual labor on the temple opened the way for them to once again do baptismal work in the Mississippi River. On Monday, 30 May 1842, Wilford Woodruff wrote of being baptized for the dead in the river under the hands of George Albert Smith and added, “I also baptized brother John Benbow for six of his dead kindred and his wife for six of her dead friends.”[44] Harrison Burgess wrote, “Sabbath day in August [1843], I was called on to administer baptism in the Mississippi River. On this occasion I administered one hundred and sixty baptisms before I came out of the water.”[45]

A visitor to Nauvoo, Charlotte Haven, observed these later river baptisms with a friend as they walked along the river bank. “We followed the bank toward town, and rounding a little point covered with willows and cottonwoods, we spied quite a crowd of people, and soon perceived there was a baptism. Two elders stood knee-deep in the icy water, and immersed one after another as fast as they could come down the bank. We soon observed that some of them went in and were plunged several times. We were told that they were baptized for the dead who had not had the opportunity of adopting the doctrines of the Latter Day Saints.”[46]

So frequent were river baptisms that William Marks, president of the Nauvoo Stake, convened a conference for the purpose of appointing recorders for baptisms for the dead wherever they occurred. Additional records still lacked proper recording, but this did not stop the Latter-day Saints from wading into the Mississippi. It was not until the death of Joseph Smith on 27 June 1844 that river baptisms stopped. As the Saints mourned his loss, even the wooden font on Temple Hill stood still.

Not until Brigham Young returned to Nauvoo in August 1844 was the question of resuming this great work for the dead raised. Brigham replied that he “had no counsel to give upon that subject at present, but thought it best to attend to other matters in the meantime.”[47] Other Apostles held differing views. In August 1844, Wilford Woodruff and his wife Phoebe went into the Mississippi River “to be baptized for some of our dead friends.”[48] On the afternoon of 24 August 1844, “several of the Twelve Apostles were baptized for their dead” in the font.[49] The work of baptizing for the dead continued until January 1845. By this time 15,722 recorded baptisms for the dead had been performed.

The Stone Font

In January 1845, the wooden font was removed from the Nauvoo Temple site. Joseph Smith had expressed his premonition that the wooden font was only a temporary structure. He said to Brigham Young that “this fount has caused the Gentile world to wonder,” and then he added that “a sight of the next one will make a Gentile fade away.”[50] It was Brigham Young who on 6 April 1845 announced the need for a new font: “There was a font erected in the basement story of the Temple, for the baptism of the dead, the healing of the sick and other purposes; this font was made of wood, and was only intended for the present use; but it is now removed, and as soon as the stone cutters get through with the cutting of the stone for the walls of the Temple, they will immediately proceed to cut the stone for and erect a font of hewn stone. This font will be of an oval form and twelve feet in length and eight wide, with stone steps and an iron railing; this font will stand upon twelve oxen, which will be cast of iron or brass, or perhaps hewn stone.”[51]

On 6 June 1845, nearly six months after Brigham’s announcement, architect William Weeks was invited to meet with “the Twelve to discuss the work of replacing the wooden baptistery with a stone one.”[52] Weeks agreed with the plans, and Brigham Young agreed to supervise the font construction. “We have taken down the wooden fount that was built up by the instructions of Brother Joseph,” said Brigham Young to an assemblage of the Saints. “This has been a great wonder to some, and says one of the stone-cutters the other day, ‘I wonder why Joseph did not tell us the fount should be built of stone.’ The man that made that speech is walking [in] darkness. He is a stranger to the spirit of this work and knows nothing. In fact he does not know enough to cut a stone for the house of God. There is not a man under the face of the heavens that has one particle of the spirit about him, but knows that God talks to men according to their circumstances.”[53]

The first stone for the new font was laid on 25 June 1845 by stonecutters after they finished their daily work on the temple.[54] Through their combined labors, they erected a font that resembled the discarded wooden structure—but with more intricate details. For example, their cutting of the stone oxen was “perfectly executed so that the veins in the ears and nose were plainly seen.”[55] The “horns were perfectly natural, with small wrinkles at the bottom.” And each stone ox was painted white and “had the appearance of standing in water halfway up to their knees.” The craftsmen even constructed an iron railing to protect the font from “the soiling hand of the curious visitor.”[56]

Visitor Buckingham wrote a description of the stone font: “The font is of white lime-stone, of an oval shape, twelve by sixteen feet in size on the inside, and about four and a half feet to five feet deep. It is very plain, and rests on the backs of twelve stone oxen or cows, which stand immersed to their knees in the earth. It has two flights of steps, with iron banisters, by which you enter and go out of the font, one at the east end, and the other at the west end. The oxen have tin horns and tin ears, but are otherwise of stone, and a stone drapery hangs like a curtain down from the font, so as to prevent the exposure of all back of the four [fore] legs of the beasts.” [57]

On 20 January 1846, the Times and Seasons reported that “the Font, standing upon twelve stone oxen, is about ready.”[58] But a certificate dated 16 December 1845 in the Archives of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints suggests that Theodore Rogers had “privilege of the Baptismal Font” prior to the newspaper announcement.[59] This corresponds to the time in which the endowment was being given in the upper story of the Nauvoo Temple. However, a question remains as to who used the font and whether baptisms for the dead were actually performed there. We know that on one occasion, “Young men and maidens came with festoons of flowers to decorate the twelve elaborately carved oxen, upon which rested the baptismal laver,” yet we are uncertain about whether baptisms were performed.[60]

Preparations to Go West

If baptisms were not performed in the stone font, then the question should be asked, “Why did the Saints not continue with this important work?” The answer is not found in neglect but in a change of emphasis. The Saints had turned their energy to receiving their endowments in the upper story of the Nauvoo Temple and making preparations for the trek west. Perhaps stonecutter Joseph Hovey described it best on 1 December 1845: “I finished my work on the baptismal font and made arrangement to . . . put up a shop and go to work ironing wagons to go to California.”[61]

The great work for the dead ended in Nauvoo in 1845. Only faded holographic baptismal records remain to tell of the unselfish deeds of the early Saints in behalf of their deceased loved ones. Saints of today should express gratitude for the deeds of the early Saints and for the records that reveal the first “ordinance remembrances” in behalf of the deceased in this dispensation.

Notes

[1] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2d ed., rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 2:380; hereafter cited as HC.

[2] Elders’ Journal 1 (July 1838): 43. Answers to the twenty questions in the Elders’ Journal bear the editorial pen of Joseph Smith.

[3] Seymour Brunson, son of Reuben Brunson and Sarah Clark, was born 18 September 1798 in Orwell, Addison County, Vermont. He was baptized in January 1831 and ordained an elder on 21 January 1831. He served on the Far West and Nauvoo High Council. He was a major in the Far West Militia, a lieutenant-colonel in the Nauvoo Legion, and a colonel in the Hancock County Militia (see “A Short Sketch of Seymour Brunson, Sr.,” Nauvoo Journal 4 (spring 1992): 3–5.

[4] Arlene Bishop Hecker, “History of Seymour Brunson,” (n.p., n.d.), 4; copy in author’s possession.

[5] Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, The Words of Joseph Smith (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1980), 49.

[6] Ehat and Cook, The Words of Joseph Smith, 49.

[7] HC, 4:179.

[8] Journal History of the Church, 15 August 1840, as quoted in Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 49.

[9] Journal History of the Church, as quoted in Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 49.

[10] Journal History of the Church, as quoted in Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 49.

[11] Joseph Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 179.

[12] Wandle Mace, Autobiography, typescript, 94, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[13] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 8:228.

[14] HC, 4:569; D&C 128:16.

[15] Wilford Woodruff, Journal, 6 April 1891, Archives of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

[16] HC, 4:426.

[17] Bathsheba Smith, “Recollections,” Juvenile Instructor 27 (1892): 344.

[18] Aroet Hale, Autobiography, typescript, 7–8, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[19] Wilford Woodruff, Journal, 6 April 1891.

[20] William Clayton, Journal, 9 May 1841, Archives of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

[21] “Local congregations were granted much latitude in the performance of vicarious baptisms. The Quincy Branch, for example, met in November 1840 and appointed two brethren, James M. Flake and Melvin Wilbur, to officiate in all of the branch’s proxy baptisms” (M. Guy Bishop, “‘What Has Become of Our Fathers?’ Baptism for the Dead at Nauvoo,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 23, no. 2 [summer 1990]: 87–88).

[22] Wilford Woodruff, Journal, 6 April 1891.

[23] HC, 6:313.

[24] Jonah Ball, letter to relatives, 19 May 1843, in Bishop, “What Has Become of Our Fathers?” 93.

[25] Sally Carlisle Randall, letter to family, 21 April 1844, Ball, letter to relatives, in Bishop, “What Has Become of Our Fathers?” 93–94.

[26] Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, 308.

[27] HC, 4:426.

[28] Andrew Jenson, The Historical Record (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson, 1889), in Dale Verden Boman, “The LDS Temple Baptismal Font: Dead Relic, or Living Symbol” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1985), 8.

[29] Descendants of John Carling claim that he drew and carved the model for the first ox (see “John Carling” [n.p., n.d.], 2, Lands and Records Office, Nauvoo, Illinois).

[30] HC, 4:446.

[31] Nauvoo Neighbor, 12 June 1844, 3.

[32] New York Spectacular, in Boman, “The LDS Temple Baptismal Font,” 32.

[33] Graham’s American Monthly Magazine 34 (1849): 257; see also Improvement Era, July 1962, 516.

[34] Emily M. Austin, Mormonism; or Life among the Mormons, in Boman, “The LDS Temple Baptismal Font,” 6.

[35] Cincinnati Atlas, clipping, Harvard Library—MSAM W-2213, in Joseph Earl Arrington, “History of the Construction of the Nauvoo Temple,” Archives of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

[36] Excerpts from the diary of George Moore, 1, in Donald Q. Cannon, “Reverend George Moore Comments on Nauvoo, the Mormons, and Joseph Smith,” Western Illinois Regional Studies 5 (spring 1982): 6–16.

[37] Boman, “The LDS Temple Baptismal Font,” 10.

[38] Stephen Joseph Morman, Autobiography, typescript, 5, Lands and Records Office, Nauvoo, Illinois.

[39] Willard Richards, George A. Smith, and Wilford Woodruff performed the confirmations (see HC, 4:454).

[40] Edward Stevenson, Selections from the Edward Stevenson Autobiography, 1820–1897, ed. Joseph Grant Stevenson (Provo, Utah: Stevenson’s Genealogical Center, 1986), 83.

[41] Joseph Hovey, Journal, typescript, 16, Lands and Records Office, Nauvoo, Illinois.

[42] Bishop, “What Has Become of Our Fathers?” 88; Nauvoo Baptisms for the Dead, Book A, Archives of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

[43] HC, 5:141.

[44] Wilford Woodruff, Journal, 6 April 1891.

[45] Statement of Harrison Burgess, Recorded 1 August 1845 by Bradford [W. Elliott], Lands and Records Office, Nauvoo, Illinois.

[46] Charlotte Haven, “A Girl’s Letters from Nauvoo,” Overland Monthly 16 (July–December 1890): 629–30.

[47] HC, 7:254.

[48] Scott G. Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal (Midvale, Utah: Signature Books, 1985), 2:455.

[49] HC, 7:261.

[50] Boman, “LDS Temple Baptismal Font,” 10.

[51] HC, 7:358.

[52] Joseph Earl Arrington, “William Weeks, Architect of the Nauvoo Temple,” BYU Studies 19 (spring 1979): 350.

[53] Dale Verden Boman, “The LDS Temple Baptismal Font,” 10.

[54] The men selected to cut the stone for the font were William W. Player, Benjamin T. Mitchell, Charles Lambert, William Cottier, Andrew Cahoon, Daniel S. Cahoon, Jerome Kimpton, Augustus Stafford, Ben Anderson, Alvin Winegar, William Jones, and Stephen Hales Jr. Stone artisan Francis Clark, who arrived in Nauvoo in April 1841, did much of the fine carving on the oxen.

[55] Austin, Mormonism; or Life Among the Mormons, in Boman, “The LDS Temple Baptismal Font,” 6.

[56] L. O. Littlefield, letter from Nauvoo to the editor of the New York Messenger, 30 August 1845, in Arrington, “History of the Construction of the Nauvoo Temple.” See also Virginia Harrington and J. C. Harrington, Rediscovery of the Nauvoo Temple: Report on Archaeological Excavations (Salt Lake City: Nauvoo Restoration, Inc., 1971), 32.

[57] Harrington, Rediscovery of the Nauvoo Temple, 33.

[58] Times and Seasons, 20 January 1846.

[59] Harrington, Rediscovery of the Nauvoo Temple, 33.

[60] Harpers Monthly Magazine 6 (April 1853): 615, in Arrington, “History of the Construction of the Nauvoo Temple.”

[61] Joseph Hovey, Journal, 1 December 1845, 26.