Teaching the Poetry of Latter-day Saint Scripture

Roger G. Baker

Roger G. Baker, “Teaching the Poetry of Latter-day Saint Scripture,” Religious Educator 3, no. 2 (2002): 201–214.

Roger G. Baker was an associate professor of English at BYU and emeritus professor at Snow College in Ephraim, Utah when this was published.

Comfort ye,

comfort ye my people. (Isaiah 40:1)

[1] Heaven knows we need the comfort, and so do the students who come to our classes. Why does God give it to us in the form of two parallel lines quoted from Isaiah? Why poetry instead of discourse or prose? At least a third of the Old Testament comes to us in poetic form, and the other standard works are sprinkled with poetry as lavishly as mountain flowers on a green meadow. Why so much poetry in scripture? Maybe God gives us His comfort in poetic form because of this form’s potent effect, because poetry works deeper and more lastingly than the prescriptive drugs of archaic prose, or because poetry gets further into our systems and does more ultimate good.

Poetry is more comforting than other forms of expression. In using Isaiah’s poetic repetition as the first words of the Messiah, Handel multiplied the biblical repetition, having the tenor sing the passage twice in the recitative like a mother soothingly rubbing her child’s hurt. Poetic repetition works well for other reasons besides the additional comfort. We remember the poetic because of the repetition, especially when it includes a crescendo of an idea. In the first phrase of Isaiah’s poem, we aren’t sure who “ye” is. When the second line amplifies the idea to “ye people,” it makes “ye” the people of the speaker, God’s people. Comfort is for His people, even people who live at different times and in different countries and speak different languages. We are the “my people” of this poem in Isaiah.

So the poetry becomes ours as we read ourselves into it. And everybody can. Putting the poetry into repetition of an idea, as Isaiah does, not only makes the idea memorable but also makes the idea something we feel is translatable into other cultures. Meter and rhyme can seldom survive the shift to different kindreds, tongues, and peoples, but the idea of comfort can.

Isaiah’s poem continues:

The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness,

Prepare ye the way of the Lord,

make straight in the desert a highway for our God.

Every valley shall be exalted,

and every mountain and hill shall be made low:

and the crooked shall be made straight,

and the rough places plain:

And the glory of the Lord shall be revealed,

and all flesh shall see it together:

for the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it. (Isaiah 40:3–5)

The voice crying in the wilderness is the voice of John the Baptist quoting Isaiah (see Matthew 3:1–3). This message offers comfort, and the poem tells us how to get it: prepare a way for the coming of the Lord. It even shows us how to do that: make a straight highway for God in the desert. It gives detailed instructions for that special highway building—the laying out, the leveling, the grading. This straight highway is wider than a straight and narrow path because it is God’s highway. It may even foreshadow the way on which Jesus made His triumphal entry into Jerusalem as prophesied in Zechariah 9:9 (see Matthew 21:1–11).

These “lines upon lines” follow each other organically, with lines coupled each to each in natural symmetry. The exalted valley is followed by the low mountain—two contrasting views of the same landscape. The crooked is straightened and the rough becomes smooth—one idea seen from two angles. Finally, when God steps onto His highway and walks toward us, the fully integrated glory is revealed, and we all see it together. That natural crescendo from revelation to actual seeing sums up the miraculous movement of scriptural poetry.

That conceptual poetry allows all to see it together in our own language, just as it says in Doctrine and Covenants 90:11:

For it shall come to pass in that day,

that every man shall hear the fulness of the gospel

in his own tongue,

and in his own language,

through those who are ordained unto this power,

by the administration of the Comforter,

shed forth upon them for the revelation of Jesus Christ.

Our modern technology struggles toward simultaneous translation, but something gets lost in the translation as computers speak with Fortran tongue. What God tore asunder at the biblical tower we try to make as one, translating our scriptures so that all the world will not only hear the message together but experience the same beauty. The miracle of biblical poetry is that its essential poetic qualities reach across cultures. Nothing is lost in the translation.

The King James Version

The Bible “is by and large a shaped text. Someone (or some One) who deeply loved language, cared about form, and was sensitive to literary structure and not averse to the sheer delights of wordplay passed a hand over the text and crafted it in certain ways.”[2] Jewish novelist Chaim Potok’s words describe no translation of the Bible better than the King James Version (KJV). The 1611 translators, steeped in the language of Shakespeare, obviously in love with words, crafted a remarkably poetic translation.

The KJV is neither the most up-to-date translation nor the most historically reliable. Joseph Smith thought Martin Luther’s German translation more accurate than other translations. Nor does the fact that the KJV remains the most widely used English Bible explain fully why it is the Bible of Joseph Smith and the Restoration.[3] A surprising part of the reason the King James translation has become the official Bible of Latter-day Saints is that it contains some of the most important poetry in the world. That literary quality becomes apparent when we read other translations of Genesis 1:4 [4]

KJV (1611) And God saw the light, that it was good.

NEB (1946–70) And God saw that the light was good.

NAB (1970) God saw how good the light was.

NJB (1985) God saw that light was good.

NRSV (1989) And God saw that the light was good.

REB (1989) And God saw the light was good.

Since “we believe the Bible to be the word of God as far as it is translated correctly” (eighth article of faith), we should desire to look closely at the light in these disparate translations for both poetic and theological differences. When we ask students at Brigham Young University if they see differences in the translations of this passage, they usually tell us that the KJV seems more poetic. The KJV is the only translation that includes that pause in the middle, the pause creating a balanced poetic rhythm on each side of the comma. There was no punctuation in ancient Hebrew, but the King James translators have captured well here the feel of its poetry. The idea after the pause builds on the previous idea in the same natural crescendo we saw in Isaiah.

Readers may also discern a theological difference—the King James translation makes God the principal actor. He sees to it that light is good. In other versions, He seems rather to notice that it is good. The NJB has the most passive God, who merely notices that “light was good.” The NAB translators assume that degrees of goodness exist, writing “God saw how good the light was”; and readers of the NAB could wonder if there is somewhat good light, good light, awesome light. The Joseph Smith Translation emphasizes those differences more emphatically, preserving the poetic pause with a semicolon and putting the passage in first person so that God is the speaker. Moses 2:4 puts it: “And I, God, saw the light; and that light was good.”

Beyond those describable differences, many of us feel something within the phrasing of the King James Version that makes it the best in our literary ears. An argument can be made that some current, modern language translations may be more accurate because they use such older sources as the Dead Sea Scrolls.[5] But to many readers, the KJV reads as if it were translated in a time when people delighted in reading the Bible aloud, and those Renaissance voices remain as music in our modern ears.

The Essence of Scriptural Poetry[6]

Italians have a cynical saying that translations are like wives: the beautiful ones are not faithful, and the faithful ones are not beautiful. The difficulty of translating poetry can be seen in translations of Japanese haiku. A precise language translation should preserve both the five-seven-five syllable count and the rhyme of the first line with the third, but this is impossible if the meaning is to be translated. The translators of the version below on the left, Earl Miner and Babette Deutsch, try to preserve the syllable count. The translations on the right, by Harold G. Henderson, preserve the poetic structure by making the first and third lines rhyme.

| The lightning flashes! | A lightning gleam: |

And slashing through the darkness, A night-heron’s screech. | Into darkness travels A night heron’s scream |

| (Matsu? Bash, 1644–94) | |

The falling flower I saw drift back to the branch Was a butterfly. | Fallen flowers rise Back to the branch—I watch: Oh . . . butterflies! (Moritake, 1452–1540)[7] |

When reading these English translations of Japanese poetry, we might wonder what the original sounded like and how much is lost in the translation. Now imagine that instead of translating Japanese poetry, we have the assignment to translate sacred text from its first language to a second—the most important poetry ever written, scripture.

Luckily, in scripture the essential qualities are translatable. That process is so natural that as readers we often do not even recognize we are reading scriptural poetry. Only three of the forty-two chapters of the book of Job are not poetry. All passages except the first two chapters and verses 7 through 17 in the last chapter are written in a poetic form in most modern translations, just as the verses from Isaiah that began this article are written. But though our Authorized Version is much more poetic than modern language translations, its poetry wasn’t printed in poetic form as it is in this article, in some cases because the translators thought they were translating ideas, not poetic forms.[8]

Parallelism

The essence of Hebrew poetry and other ancient sacred poetry is thought rhyme, two glances at a similar idea. The glances are usually separated by a pause. Sacred literature that has this parallel thought rhyme includes poetry in the literature of Qumran, Ugaritic texts, Sumero-Akkadian literature, ancient Greek and Latin literatures, the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Bible. There is a good review of this ancient poetry in Chiasmus in Antiquity, edited by John Welch.[9] It seems thoroughly appropriate that the most translated poetry, biblical poetry, retains its most important poetic quality in translation.

Parallel poetry was first recognized by Bishop Robert Lowth in 1753 in his Lectures on the Sacred Poetry of the Hebrews, as described in The Bible as Literature: “The key to Hebrew poetry . . . is that it is a structure of thought rather than of external form and that a Hebrew poem is composed by balancing a series of sense units against one another according to certain simple principles of relationship.”[10]

You can easily experience the effect of parallel thought rhyme in class or in the privacy of your own home without appearing unduly stupid. Hold an arm out straight and, with one eye closed, point to a small object like a light switch, thermostat, or mark on the wall. After the object is in sight, keep the pointing arm still and change eyes. It appears your aim is off. Blinking from eye to eye will make it look as if the aim changes for each eye when, in fact, the aim stays the same. Each eye takes a slightly different picture from a slightly different angle.

When we look with both eyes open, the two different snapshots are merged into one complete picture. Our brain puts the two pictures together so we get depth perception. If we had only one eye, we would lose our sense of depth, our three-dimensional view of our world. Sacred literature, with its two looks at the same idea, provides us spiritual depth perception, a good argument for teaching the poetry of scripture:

The heavens declare the glory of God;

and the firmament showeth his handywork. (Psalm 19:1)

“Heavens” and “firmament” are synonyms. “Declare” and “showeth” are synonyms. “Glory of God” and “handiwork” are near synonyms. Both lines look at the same ideas from a slightly different angle. This most common type of parallelism, synonymous parallelism, is easiest to recognize:

Wash me throughly from mine iniquity,

and cleanse me from my sin. (Psalm 51:2)

He maketh the deep to boil like a pot:

he maketh the sea like a pot of ointment. (Job 41:31)

He that sitteth in the heavens shall laugh:

the Lord shall have them in derision. (Psalm 2:4)

Linguists reinforce the idea that each view from the literary binocular is slightly different by suggesting that no true synonyms are possible. No matter how close the meaning of two words, they are not actually synonyms unless they do not change meaning. In that nonrepeatability principle lies the craft of parallel poetry. The second line must parallel the first but at the same time be different from the first. The second line adds to the idea of the first, amplifying or altering or adding to it.

Obvious as the poetic form of the Bible seems to us, we should keep in mind that no distinction may have existed between poetry and prose to the early Bible writers. James L. Kugel points out that biblical Israelites had no terms corresponding to poetry and prose, so “there is no indication that they thought of their sacred writings as falling under one of these two general headings.”[11] The idea that the poetry was not written self-consciously makes the scriptures even more remarkable, suggesting the hand of some One who inspires His scribes.

The opposite kind of parallelism from synonymous is antithetical. In this, the second contrasts with the first when the writer presents an opposite thought:

A virtuous woman is a crown to her husband:

but she that maketh ashamed is as rottenness in his bones. (Proverbs 12:4)

Antonyms are less obvious than synonyms, but we can see that a “virtuous woman” is in some ways the opposite of “she that maketh ashamed” and that “a crown to her husband” is the opposite of “rottenness in his bones.” “Chariots” and “horses” aren’t exactly opposite, but they are different in function, the one pulling, the other pulled:

Some trust in chariots,

and some in horses. (Psalm 20:7)

Three more examples may make us more aware of the pattern of antithetical parallelism:

He asked water,

and she gave him milk. (Judges 5:25)

For the Lord knoweth the way of the righteous:

but the way of the ungodly shall perish. (Psalm 1:6)

My son, keep thy father’s commandment,

and forsake not the law of thy mother. (Proverbs 6:20)

Climactic and synthetic parallelism are so similar we can group them as synthetic. Synthetic parallelism, instead of echoing or contrasting, completes:

The Lord reigneth;

let the earth rejoice. (Psalm 97:1)

In this form, the idea grows with the addition of each parallel line:

When I consider thy heavens, the work of thy fingers,

the moon and the stars, which thou hast ordained;

What is man, that thou art mindful of him?

and the son of man, that thou visitest him?

For thou hast made him a little lower than the angels,

and hast crowned him with glory and honour.

Thou madest him to have dominion over the works of thy hands;

thou hast put all things under his feet:

All sheep and oxen, yea, and the beasts of the field;

the fowl of the air, and the fish of the sea,

and whatsoever passeth through the paths of the seas. (Psalm 8:3–8)

The progress is line upon line: after heavens with moon and stars are ordained, we see man, and the Psalmist asks why Jehovah is mindful of man. We then learn that man is only a little lower than the angels and, in a natural progression of idea, crowned with glory, with dominion over works of his hands and under his feet. That dominion is emphasized when the writer specifies that oxen, beasts, fowls, and fish are under the dominion of man.

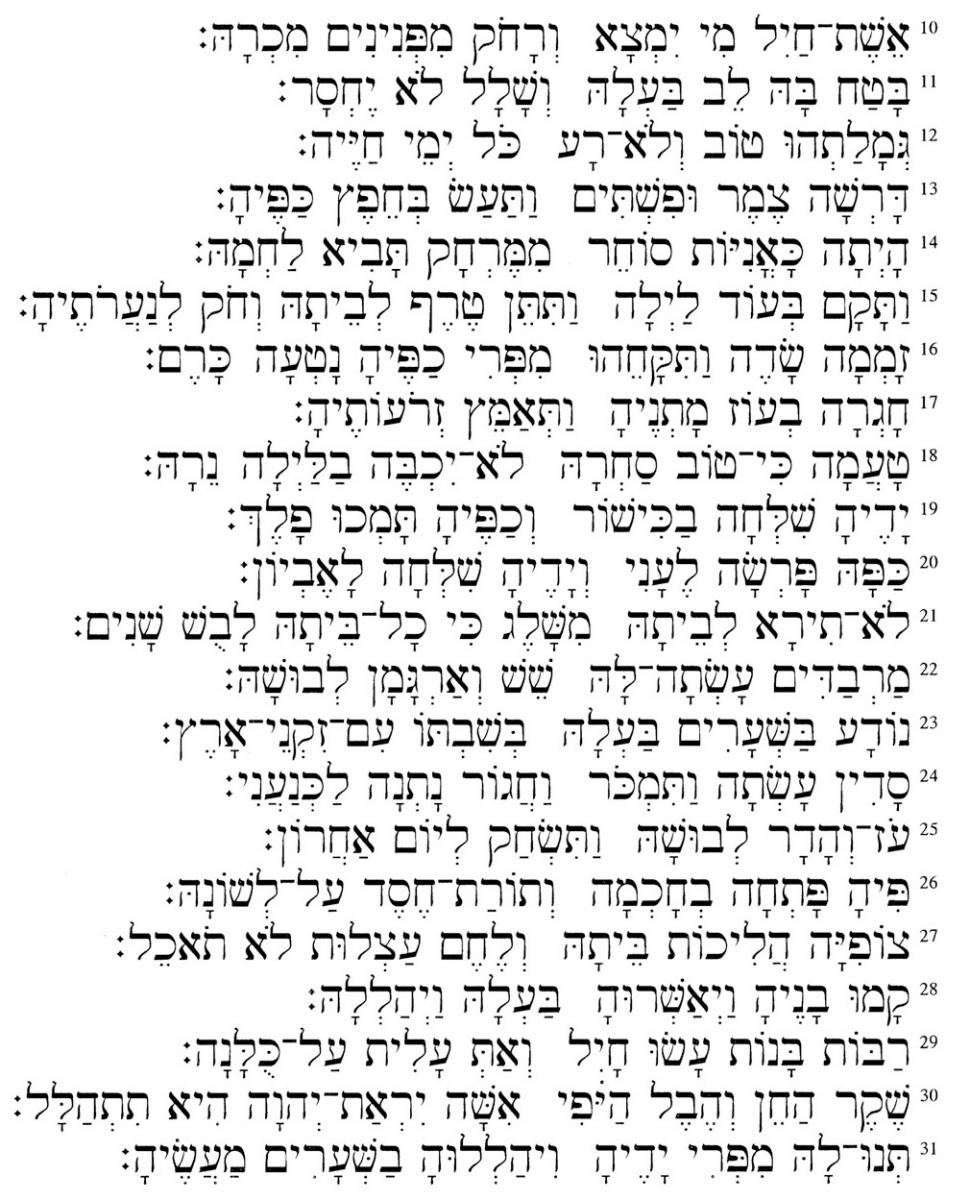

The form of parallelism can be seen in Hebrew even by those of us who do not read Hebrew. Look at the modern Hebrew version of Proverbs 31:10–31, the virtuous woman:[12]

Notice that gap in the center of each line, the blank line that weaves its way vertically down the text? That’s the division between this list of parallel thoughts. The idea is more obvious in the NRSV translation that is titled Ode to a Capable Wife.

There is something else poetic in these superb lines. English borrowed the word alphabet from the first two letters of the Hebrews, aleph ` ttt and beth ttt. The first line of the Proverbs poem begins with aleph, the second with beth, and the poem continues with each letter of the Hebrew alphabet in order. The use of letters this way in a poem is called an acrostic. It is a poetic form we use when we write a poem with each line starting the letter of some name:

ttt M is for the many things she gives me.

O is that she’s only growing old.

T is for the tears she said to save me.

H if for her heart as pure as gold. . . ttt And so on until the students gripe how “cheesy” this is, even for MOTHER.

Parallelism characterizes poetry in all scripture, not just the Bible. The promise in Doctrine and Covenants 89:18–21 for those who keep the Word of Wisdom is pure poetry:[13]

And all saints who remember to keep and do these sayings,

walking in obedience to the commandments,

shall receive health in their navel

and marrow to their bones;

And shall find wisdom and great treasures of knowledge,

even hidden treasures;

And shall run and not be weary,

and shall walk and not faint.

And I, the Lord, give unto them a promise,

that the destroying angel shall pass by them,

as the children of Israel,

and not slay them.

Notice that the first two lines are parallel and that each following pair is also parallel.

Chiasmus

After getting used to some of the principles of parallel lines, we can easily notice a common and elegant pattern in scriptural poetry: chiasmus. The form is named for the Greek letter chi (ttt), which originally represented the back-and-forth motion of plowing a field. Like parallelism, it is intimately related to the way we see.

When each eye takes a picture from a slightly different angle, it projects the image on the retina at the back of the eyeball. Nerves from the retina separate, some from each eye going to each side of the brain. The point at which the nerves cross is called the optic chiasm, a suggestion that our eyes and brain may be hardwired for this chiastic form.

The chiasm of scriptural poetry is like the refreshing reflection of the mountain in the lake. The reflection and the mountain converge at the base. The summit of the mountain and the summit of the reflection are parallel ideas. The lake is never perfectly still, so the real image and the reflected image are always a little different; but on a still day, we have difficulty telling which image is which. The dual view offers depth.

The structure of the chiasm is A/

A

B

C

D

E

D’

C’

B’

A’

Two obvious examples occur in the first two verses of Psalm 76:

1. In Judah is God known: his name is great in Israel.

A In Judah

B Is God known

B’ his name is great

A’ in Israel

2. In Salem also is his tabernacle, and his dwelling place in Zion.

A In Salem also

B is his tabernacle,

B’ and his dwelling place

A’ In Zion

It gets a bit more complex in Jeremiah 2:27–28:

A but in the time of their trouble they will say,

B Arise, and save us.

C But where are thy gods

C’ that thou hast made thee?

B’ let them arise, if they can save thee

A’ in the time of thy trouble.

We might more easily visualize the ttt form if it is shown graphically the way Lynn Johnson proposes for the scripture that states the chiastic form. “But many that are first shall be last; and the last shall be first” (Matthew 19:30):

But many that are first shall be last;

and the last shall be first.[14]

Following is an extended example from Jeremiah 2:5–9 in which bold italics have been added to make the structure look more obvious:

Thus saith the Lord,

A What iniquity have your fathers found in me,

that they are gone far from me

B and have walked after vanity, and are become vain?

C Neither said they,

Where is the Lord

D that brought us up out of the land of Egypt,

that led us through the wilderness,

through a land of deserts and of pits,

through a land of drought,

and of the shadow of death,

through a land that no man passed through,

and where no man dwelt?

E And I brought you into a plentiful country,

to eat the fruit thereof

and the goodness thereof;

D’ but when ye entered, ye defiled my land,

and made mine heritage an abomination.

C’ The priests said not,

Where is the Lord?

And they that handle the law knew me not:

the pastors also transgressed against me,

B’ and the prophets prophesied by Baal,

and walked after things that do not profit.

A’ Wherefore I will yet plead with you,

saith the Lord,

and with your children’s children will I plead.[15]

Klein and Blomberg offer helpful commentary on this example. They note that C’ repeats the wording of C while D’ recalls the emphasis on land in D and that B’ clarifies the vanity in B as a reference to the prophecies of Baal’s prophets. “The terms ‘fathers’ (A) and ‘grandchildren’ [children’s children] (A’) parallel each other.” The center E line is the “structural hinge and states the text’s main point. . . . The frames, A/

Chiasmus, like parallelism, appears in all scripture. This form holds in translation and should not be thought of as just a biblical form. It is scriptural. It is found in all the standard works, as noted by John W. Welch, editor of Chiasmus in Antiquity. One example from the Book of Mormon noted by Welch is perhaps a model of the form.

As an old man blessing his firstborn son Helaman, Alma relives his conversion, but now he retells and reshapes it within a meticulous chiastic framework that not only contrasts the intense agony of his conversion with its exuberant joy but also frames that conversion with twelve precisely flanking elements that surround the focal point of that conversion, namely Alma’s reliance on “one Jesus Christ, a Son of God.”[17]

a) My son give ear to my words (1)

b) Keep the commandments and ye shall prosper in the land (1)

c) Do as I have done (2)

d) Remember the captivity of our fathers (2)

e) They were in bondage (2)

f) He surely did deliver them (2)

g) Trust in God (3)

h) Supported in trials, troubles, and afflictions (3)

i) I know this not of myself but of God (4)

j) Born of God (5)

k) I sought to destroy the church (6–9)

l) My limbs were paralyzed (10)

m) Fear of being in the presence of God (14–15)

n) Pains of a damned soul (16)

o) harrowed up by the memory of sins (17)

p) I remembered Jesus, Christ, as son of God (17)

p’) I cried, Jesus, son of God (18)

o’) Harrowed up by the memory of sins no more (19)

n’) Joy as exceeding as was the pain (20)

m’) Long to be in the presence of God (22)

l’) My limbs received strength again (23)

k’) I labored to bring souls to repentance (24)

j’) Born of God (26)

i’) Therefore my knowledge is of God (26)

h’) Supported under trials, troubles, and afflictions (27)

g’) Trust in him (27)

f’) He will deliver me (27)

e’) As God brought our fathers out of bondage (28–29)

d’) Retain in remembrance their captivity (28–29)

c’) Know as I do know (30)

b’) Keep the commandments and ye shall prosper in the land (30)

a’) This according to his word (30)[18]

Many other genres appear in scripture poetry. About 40 percent of biblical psalms are “laments,” a form that overlays parallel lines. These poems follow a five-stage format of addressing God, describing a problem, asserting faith, asking for help, and then thanking God. Many more forms of the psalm alone are evident—praise psalms, petitions, supplications, vows, and even love psalms. All those forms, like chiasm, are built upon the thought echoes of parallelism.

Though parallelism is its basic form, the poetry is not only in the parallels. The poetry is in the symbols—in the shepherd, the bread, the water. The poetry is in the meanings, the implications of psalm and parable. Most of all, the poetry is in the feelings, ultimately the spiritual feelings scriptural poetry evokes. The poetry makes us experience, makes us remember, or makes us feel. At the heart of those feelings we experience what we need most—comfort, divine comfort:

Comfort ye,

comfort ye my people.

Notes

[1] A revision of this paper has been submitted to Covenant Communications as the first chapter of a proposed book to be coauthored with Steven C. Walker. The working title of the book is Favorite Poems from Latter-day Saint Scripture. Steve also reviewed and edited this article.

[2] Chaim Potok, “The Novelist and the Bible,” in A Complete Literary Guide to the Bible, ed. Leland Ryken and Tremper Longman III (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1993), 489–98.

[3] J. Reuben Clark Jr., Why the King James Version, Classics in Mormon Literature (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1979). The 1979 edition is a reprint of the 1956 version of Clark’s book. It is mostly a review of earlier scholarship, and it summarizes most of the reasons the Church has adopted the King James Version or Authorized Translation of 1611 as the official English language Bible.

[4] The abbreviations for versions other than the King James Version (KJV) are as follows: NEB = New English Bible; NAB = New American Bible; NJB = New Jerusalem Bible; NRSV = New Revised Standard Version; and REB = Revised English Bible.

[5] The New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), translated in 1989, is the most recent example of a modern language translation that uses the Dead Sea Scrolls and so notes this in the footnotes. These emendations are noted with a Q Ms to indicate a manuscript found at Qumran by the Dead Sea. Although this translation is in the lineage of the KJV, it is not as poetic, and the effort to make the text gender neutral can be annoying.

[6] Many of the examples in this paper were first published by Roger Baker, Teaching the Bible as Literature (Norwood, Massachusetts: Christopher Gordon Publishers, 2002). The material on poetry from chapter 8 of this text is printed here by permission.

[7] Laurence Perrine, Literature: Structure, Sound, and Sense (New York: Harcourt Brace, Jovanovich, 1984), 722. This text includes both of the translations of these poems.

[8] All citations from the Bible in this article use the Latter-day Saint edition of the King James Version, but often the passages are printed in a poetic format, as are passages from the other standard works.

[9] John W. Welch, ed., Chiasmus in Antiquity: Structures, Analyses, Exegesis (Provo, Utah: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, 1981). This text is especially valuable for its index of poetic, particularly chiastic passages, in ancient texts used as sacred literature in the Church.

[10] John B. Gabel, Charles B. Wheeler, and Anthony D. York, The Bible as Literature: An Introduction (New York: Oxford, 1996) 35.

[11] James L. Kugel, The Great Poems of the Bible: A Reader’s Companion with New Translations (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999), 25.

[12] Leland Ryken, How to Read the Bible as Literature (Grand Rapids: Academe Books, 1984), 104.

[13] Brian Best of the BYU English Department showed me this passage and used it as an example in his Bible as literature course.

[14] D. Lynn Johnson, “Hidden Treasures in the Word of Wisdom,” This People, spring 1995, 48–56. This reading of section 89 of the Doctrine and Covenants explores the possibility that the entire section may be a chiasmus pointing to the central message of the Word of Wisdom.

[15] William W. Klein and others, Introduction to Biblical Interpretation, ed. Kermit A. Ecklebarger (Dallas: Word Publishing, 1993), 238. Klein indicates that the example (slightly modified) comes from W. G. E. Watson, “Chiastic Patterns in Biblical Hebrew Poetry,” in Welch, ed., Chiasmus in Antiquity, 141. Klein is cited here because of the commentary he offers.

[16] Klein and others, Introduction to Biblical Interpretation, 239.

[17] Welch, Chiasmus in Antiquity, 206.

[18] Welch, Chiasmus in Antiquity, 206.