Mark Taggart, "David W. Patten: Faithful Friend or Heel Lifter?," Religious Educator 26, no. 2 (2025): 59–74.

Mark Taggart Lewis (lewismarkt@churchofjesuschrist.org) works for Seminaries and Institutes in Tooele County and is pursuing a PhD in curriculum and instruction at Utah State University.

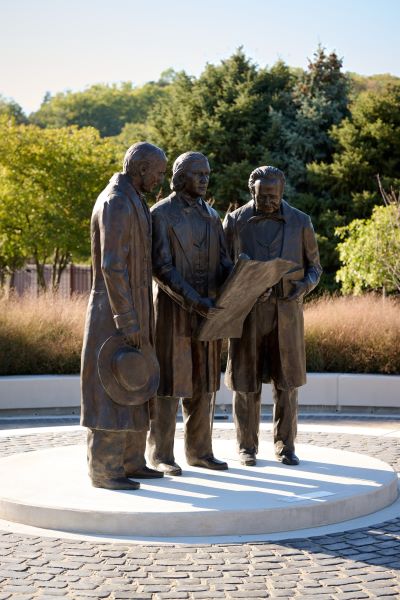

In 1843 Joseph Smith remarked, “Of the first Twelve Apostles chosen in Kirtland and ordained under the hands of Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and myself, there have been but two, but what have lifted their heel against me, namely Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

In 1843 Joseph Smith remarked, “Of the first Twelve Apostles chosen in Kirtland and ordained under the hands of Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and myself, there have been but two, but what have lifted their heel against me, namely Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

ABSTRACT: In 1843 Joseph Smith reflected on his experiences with the original members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in this dispensation, remarking that only Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball had not “lifted their heel” against him. Of the remaining ten members of the Quorum, nine faced documented disciplinary action or openly opposed Joseph, but David W. Patten did not. Patten’s loyalty, martyrdom, and frequent commendations from Joseph, the Lord, and his contemporaries make Patten’s exclusion from Joseph’s 1843 praise of Brigham and Heber puzzling. Those who knew Patten spoke at length of his faithfulness and often listed his name alongside Joseph and Hyrum as the great martyrs of the faith. Later historians, however, have spoken less favorably, suggesting that Patten’s rebellion may simply be poorly documented. Contextual clues may also suggest that because Patten died in 1838, he simply was not on Joseph’s mind when he made his 1843 remark in 1843. Ultimately, David Patten’s case serves as a caution against hasty characterizations of historical figures.

KEYWORDS: church history, 1820–1844, Joseph Smith, apostle

Under Joseph Smith’s direction, the first Quorum of the Twelve Apostles was organized and set apart in Kirtland, Ohio, on February 14, 1835. That fledgling body of leaders would face many challenges to their faith and commitment over the next few years. One of these was the collapse of the Kirtland Safety Society—part of the Panic of 1837, a national financial crisis.[1] These events tested the faith and strained the commitment of many members of the Church and most members of the newly formed Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Many Church members and some in the Quorum of the Twelve felt that Joseph had misled them to unwisely invest in the bank before its collapse. Some Apostles even went so far as to try to excommunicate Joseph Smith and other Church leaders and obtain control and leadership over the Church.[2] Joseph went to Jackson County in an effort to help hold the Church together but was met with even more difficulty when he arrived in Missouri.[3] Betrayal, rumor, suspicion, and violence erupted among the Latter-day Saints during the Mormon War in Missouri in 1838—another fierce trial of faith for Joseph and those members of the Quorum of the Twelve that were not disaffected by events related to the 1837 bank panic.

In the years that followed, Joseph witnessed official disciplinary actions against nine of the original twelve members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.[4] Reflecting on that original Quorum of the Twelve, Joseph remarked to his scribe Thomas Bullock on May 28, 1843, “Of the first Twelve Apostles chosen in Kirtland and ordained under the hands of Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and myself, there have been but two, but what have lifted their heel against me, namely Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball.”[5] Offering few clues regarding the context, Bullock dutifully recorded the comment in the official history of the Church. Joseph had come to value greatly the contributions of many of the Apostles, but he made this note of special gratitude for those two who had never worked against him and instead stood loyally by his side in the work of the unfolding restoration.

However, Joseph’s statement raises questions when reflecting on the turbulent, early times in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. First, many of the nine Apostles that worked against the Church had completely returned to full fellowship by the time Joseph made the above remark in 1843 and were contributing powerfully in God’s kingdom. Additionally, there was another Apostle besides Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball that had not received official Church discipline during the Kirtland crisis in 1837, the tribulations of the Mormon War in 1838, or the five years prior to Joseph’s comment. That Apostle was David W. Patten. How did any actions on the part of Patten compare to the actions of the other nine Apostles who had been formally disciplined? Why did Joseph imply inclusion of Patten among those who had “lifted their heel” against him if he did not see fit to officially discipline him?

The Nine Apostles Receiving Church Discipline

For the nine officially disciplined members of the original Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, each had their clear public moments of direct opposition to Joseph Smith, making Joseph’s characterization of their past interactions with him understandable. Space in this article does not allow for a detailed treatment on each of these men, but the following summary table contains the length of their disaffection, any characterizing moments of that disaffected period, and the eventual conclusion of each of these Apostles’ relationships with the Church[6]:

| Name | Length of Disaffection | Characterizing Moments | End Result of Membership |

| John F. Boynton | Disfellowshipped briefly in 1837. Excommunicated in 1838. Never returned. | Seized control of the Kirtland Temple, attempted to excommunicate Joseph (calling him a fallen prophet).[7] | Visited Joseph in Nauvoo in 1842 and the Saints in Salt Lake City in 1872 but never returned to Church membership. |

| Orson Hyde | Disfellowshipped briefly in 1835. Left the Church in October 1838, returned in January 1839, and was reinstated in the Quorum in June 1839. | Signed affidavits against the Saints in Missouri.[8] | President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. |

| Luke S. Johnson | Disfellowshipped with Lyman in September 1837 for a few days. Excommunicated in April 1838, until reuniting with the Saints in 1846. | Seized control of the Kirtland Temple, attempted to excommunicate Joseph (calling him a fallen prophet). | Bishop in Salt Lake Valley. |

| Lyman E. Johnson | Disfellowshipped for a few days in September 1837. Excommunicated April 11, 1838, and never returned. | Seized control of the Kirtland Temple, attempted to excommunicate Joseph (calling him a fallen prophet). | Excommunicated former member—never returned to the Church. |

| Thomas B. Marsh | Excommunicated from the Church in absentia on March 17, 1839. | Signed affidavits against the Saints in Missouri. | Rejoined the Church in Utah in 1857. |

| William E. McLellin | Briefly disfellowshipped in 1835. Excommunicated in fall 1837 and never returned. | Criticized the wording of the Doctrine and Covenants, rebuked the Presidency frequently, joined Missouri mobs in pillaging Far West. | Associated briefly with several different Latter-day Saint movements, concluding with the Hedrickites. |

| Orson Pratt | Faltered briefly in 1837.[9] Excommunicated in August 1842, rebaptized months later. Reinstated in the Quorum of the Twelve in January 1843. | Faith shaken during 1837 financial crisis, serious conflict between himself and Joseph over his wife, Sarah Pratt.[10] | Served faithfully as an Apostle until his death. |

| William Smith | Temporarily suspended from the Quorum of the Twelve in 1838. Suspended again in May 1841. Excommunicated in October 1845 by Brigham Young. | Frequent battles and physical altercations with Joseph and opposition to other Church leaders.[11] Failure to fulfill assignments. | Briefly affiliated with other Latter-day Saint groups, eventually joining the RLDS movement. |

| Parley P. Pratt | Temporarily disaffected from the Church and tried by the Kirtland high council. While the council found him guilty, there is no record of his being excommunicated or disfellowshipped. | During the 1837 financial crisis, spoke out against Joseph Smith and brought charges against the Prophet.[12] Publicly preached against Joseph.[13] Made efforts to persuade John Taylor away from the Church.[14] | Moved West with the Saints to Utah and served many missions for the Church before being murdered on a mission in Arkansas. |

The Case of David W. Patten

David Patten’s implicit inclusion on the list of those who “lifted the heel” is a puzzling one. Many biographers write only glowingly of Patten’s faith and commitment to the Church, despite Patten’s fatal involvement in a misguided enterprise in Missouri that resulted in the death of several Latter-day Saints and himself, placing him among the Church’s first martyrs. While Patten lay dying, Joseph noted that among the final words Patten spoke to his spouse was the plea, “O! do not deny the faith.”[15] In the days surrounding Patten’s death and funeral, Joseph recorded his contemporaneous opinion of Patten—that he was “a very worthy man, beloved by all good men who knew him . . . , a man of God; and strong in the faith.”[16] Relevant to the thesis of this article, Joseph also recorded an explicit contrast between Patten and an Apostle the Church had taken action against: “how different his fate from that of the Apostate Thomas B. Marsh.”[17] After Patten’s death but before his funeral, Joseph visited David’s home and remarked, “There lies a man who has done just as he said he would—he has ‘laid down his life for his friends.’”[18] In a revelation given a few years later on January 19, 1841, the Lord used Patten’s life as an ideal example, urging the Saints to finish their work so that God may receive them “even as I did my servant David Patten” (Doctrine and Covenants 124:19). Later in the same section, the Lord declares, “David Patten I have taken unto myself; behold, his priesthood no man taketh from him” (v. 130). David Patten’s ministry was filled with a dozen short missions and numerous healings and other miracles. He stood up to mobs, spoke truth boldly, and refused to back down in the face of opposition.[19] David Patten was beloved by the Church, Joseph Smith, and the Lord. So why, then, was he not lauded with Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball when Joseph made his remarks regarding the original Quorum of the Twelve Apostles?

Hypothesis 1: Patten’s Opposition to Joseph Is Simply Less Well-Known

Perhaps David Patten did have a moment of serious disaffection or conflict with Joseph Smith that has simply gone uncirculated or—at the least—simply has not been circulated well in the more frequently trod portions of Church history. Such lesser-known factors could explain why Joseph’s 1843 statement excluded him from the company of Heber C. Kimball and Brigham Young.

Patten’s Rebuke from God in 1835

In a revelation dated November 3, 1835, that is not part of the Doctrine and Covenants, the Lord rebukes many of the Twelve for not living the law of consecration as fully as they ought: “Nevertheless the sin which he [William Smith] hath sinned against me, is not even now more grievous than the sin with which my Servant David W. Patten, my Servant Orson Hyde, and my Servant Wm. E. McLel[l]in, have sinned against me, and the residu are not sufficiently humble before me.”[20] The Lord goes on to rebuke the Twelve regarding their temporal inequality. While this does show that David Patten was not above reproach, it would be extreme to assert that this revelation is why Joseph included him with the ten “heel lifters” in his 1843 remark. Additionally, this rebuke is coming from God to help David Patten more fully live the commandments, not to correct open rebellion. Joseph’s remark in 1843 is about those members of the original Quorum of the Twelve Apostles that had lifted the heel against him specifically, not brief moments where they needed correction or guidance from the hand of God.

Wilford Woodruff’s Recollection in 1857

Another possibility of a lesser-known incident is put forward by Wilford Woodruff. In June 1857—fourteen years after Joseph’s original statement and twenty years after the events they describe—Wilford Woodruff records in his journal a conversation he witnessed involving himself, Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, George A. Smith, Amasa Lyman, and Charles C. Rich. These men were gathered in an office in downtown Salt Lake City, reminiscing. Woodruff records:

President B Young ^& H C Kimball^ G. A. Smith A Lyman & C. C. Rich came into the office at 2 oclok & sat & conversed upon various things. He [President Young[21]] said that David Patten & T. B. Marsh came to Kirtland in the fall of 1837. He said as soon as they came I got Marsh to go to Josephs But Patten would go to W Parrish He got his mind prejudiced & when He went to see Joseph David insulted Joseph & Joseph slaped him in the face & kicked him out of the yard this done David good.[22]

This brief physical conflict recollected by Brigham Young could explain Patten’s implicit inclusion as a “heel lifter” in Joseph Smith’s 1843 comment. However, surrounding context in Wilford Woodruff’s record indicates that President Young’s anecdote above was immediately followed by another recollection from Charles C. Rich recounting the circumstances of Patten’s death and martyrdom—an event that is the greatest demonstration of Patten’s faithfulness. This could suggest that Brigham Young’s story was not shared in an effort to criticize Patten and possibly that the originating context for this remembrance may have more to do with the other individual in Young’s remembrance. That same day—June 25, 1857—Woodruff records that Thomas B. Marsh had come to visit Brigham Young in the president’s office that morning. Wrote Woodruff:

T B Marsh pleads for Mercy & askes if it is not to late for him to fill his mission B Young says yes it is but I am willing to forgive him & that he may be baptized & confirmed then let him come here.[23]

Given the connection between Marsh’s visit to President Young’s office and Marsh’s role in the first reminiscence shared in the Church Historian’s office later that afternoon, it could be inferred that the first anecdote shared about Joseph slapping Patten had initially been more about remembering Marsh than criticizing Patten. Then, as Patten had been brought up, the conversation shifted towards Patten as Charles C. Rich spoke about Patten’s death. Like Joseph’s 1838 contrasting of Patten and Marsh described earlier, this would provide a second circumstance where these two are compared—Patten again embodying an example of faithfulness.

Rather than viewing Woodruff’s recollection in 1857 as an explanation for Patten’s lack of faith, it seems more likely that these events reflect a sharing of fond remembrances regarding a mutual friend—remembrances sparked by the appearance of Thomas B. Marsh.[24] However, this particular episode does singularly point out a rare and brief moment of tension between David W. Patten and Joseph Smith—an incident that was severe enough for Joseph to strike Patten and kick him out of his yard.

Conclusions of Later Historians Regarding Patten’s Possible Disaffection

Biographer Linda Shelley Whiting references Patten’s momentary tension with Joseph in 1837 as part of her 2003 biography, David W. Patten: Apostle and Martyr. She takes the account described in Woodruff’s journal above and draws a clear causal line between what is being recollected in that Salt Lake City office in 1857 and what Joseph Smith stated in 1843.[25] She reasons that “David’s anger at Joseph Smith did not last long. The two men appear to have reconciled soon after this fight. No official Church action was ever taken against David Patten. . . . A sign that the trouble was short lived is confirmed by the fact both Thomas Marsh and David Patten started with Joseph on a mission to Canada in July 1837.”[26]

It should be noted that the details surrounding Joseph’s slapping of Patten have some incongruities. For example, Woodruff’s recollection places these events in the fall of 1837. However, in an attempt to keep things consistent with David’s arrival in Kirtland and his later departure on a mission for Canada in July, Whiting shifts the date for the apparent conflict between Patten and Joseph up to June 1837.[27] This is significant because the Kirtland apostasy had yet to reach the heights it did in August 1837 with the takeover of the temple and the attempted excommunication of Joseph Smith by dissenters. Patten’s absence from these major events that involved other apostolic dissenters places any possible momentary frustration of Patten’s in a less dire context. When set in contrast to others like Parley P. Pratt, who was present for all these events and spoke out openly in criticism of Joseph Smith, Patten comes off favorably, even if the worst is to be assumed from Brigham Young’s recollection recorded by Wilford Woodruff. In all of this, there is no contemporaneous account of any conflict between Patten and Joseph Smith—only the recollection regarding what had happened twenty years earlier. Whiting admits as much, stating, “No other record of this remarkable fight between these two physically strong, forceful men, has surfaced to date.”[28]

However, immediately following her admission that there is no other record of the conflict between Joseph and Patten, Whiting makes a leap in association and states that “the only obscure reference Joseph ever made to it [Patten and Joseph’s altercation] was in a talk on May 28, 1843, when he stated that only two of the original Twelve Apostles, Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball, had not ‘lifted their heel against’ him.”[29]

Another secondary source that makes mention of Joseph slapping Patten is a 2010 article titled “Joseph Smith and the Kirtland Crisis, 1837.” In it, Ronald K. Esplin summarizes the events between Joseph and Patten in 1837 as follows:

David Patten had his own brief crisis of faith. Although he had heard all the criticisms of Joseph, he had confidence in Joseph, loved Joseph, and believed in Joseph. Still, Patten wanted to hear both sides of the issue. He determined to hear the worst there was to hear and then see the Prophet. Thomas B. Marsh tried to convince Patten that his proposed approach was backward: he should go see the Prophet first, then talk to the dissenters. Once they arrived at Kirtland, however, Patten visited the dissenters first and got an earful. What he heard got him so worked up that when he went to see the Prophet, according to Brigham Young, “he insulted Joseph,” who kicked him out of the yard, and this experience “done David good” and quickly brought him to his senses. It was later said in Nauvoo that of all the original Quorum of the Twelve, only Brigham Young and Heber Kimball never lifted their heel against Joseph Smith.[30]

Analyzing this paragraph is difficult because some of Esplin’s sources are unclear, such as his reference to Marsh’s efforts to persuade Patten to see Joseph first (in Brigham Young’s recollection recorded by Woodruff, it seems that it was Young who was trying to persuade both Marsh and Patten to see Joseph—Young only succeeding with the former). In the end, it appears Esplin would share Whiting’s conclusion that the 1857 recollection and the 1843 statement by Joseph are linked by referencing them in separate, but intentionally juxtaposed sentences. Not directly stating an association does make Esplin appear slightly more cautious than Whiting regarding this conclusion.

Hypothesis 2: Due to Patten’s 1838 Death, He Was Out of Mind in 1843

Because Patten had died, he may have been out of sight, out of mind when Joseph’s statement was made in 1843. As noted earlier, Joseph’s remarks contemporary to Patten’s life and death praised him for his faith and dedication. Though it is not difficult to imagine Joseph making every effort to speak positively on behalf of his deceased friend, his affection for David Patten and his confidence in his goodness and faithfulness are clear—even likening Patten’s service to that of the Savior.

Contextual Clues on Joseph’s 1843 Remark

Examining the available context to Joseph’s comment given May 28, 1843, may help clarify Joseph’s feelings about Patten’s faith and consistency. Joseph’s remark was not made during a speech or public sermon, but rather as a note to his scribe, Thomas Bullock. Bullock’s note keeps the context for Joseph’s words on that occasion to a bare minimum. As sparse as events surrounding Joseph’s remark are, it was made on what seemed to be a fairly busy day. Joseph’s journal notes that he had been busy administering ordinances, praying for Saints in especially dire straits, and being sealed to his wife, Emma.[31] There is one brief entry about a meeting that began at five o’clock in the evening between Hyrum Smith, Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, Willard Richards, Newel Whitney, and James Adams in the “upper room.” Following the note about that meeting, the handwriting changes for one sentence from Leo Hawkins’s to Thomas Bullock’s—and only this one sentence—who then records Joseph’s statement about Brigham and Heber. Following that bare statement, nothing else is recorded for May 28, 1843. This leaves only the reference to the meeting that had taken place earlier that day to give immediate context to what events may have precipitated Joseph’s words. Due to the change in scribe, it seems reasonable that the meeting had concluded and that the setting had changed—at the least, Hawkins was no longer available to act as scribe. The brief, one-sentence inclusion may suggest an offhand thought or remark Joseph had made in the moment that he wanted to make part of the official record, perhaps out of gratitude for Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball, with whom Joseph had just met. While it is impossible to know for certain, the limited context suggests that Joseph’s remark may have been intended to reflect more on Heber C. Kimball and Brigham Young specifically than the other ten Apostles generally and not as an opportunity to leave out or slight David Patten in either a direct or obscure manner. There is no documented direct link between Joseph’s note in 1843 and the recollection recorded by Woodruff in 1857. To suggest that Joseph Smith was offering direct comment on his argument with Patten when he made his 1843 statement regarding the original members of the Quorum of the Twelve is unlikely and ultimately unsubstantiated.

Patten’s Reputation with His Contemporaries

Other contemporaries held Patten in high esteem as well. Wilford Woodruff mournfully wrote about his friend’s death: “Thus fell the noble David W. Patten as a martyr for the cause of God and he will receive a martyr’s crown. He was valiant in the testimony of Jesus Christ while he lived upon the earth. He was a man of great faith and the power of God was with him. He was brave to a fault, even too brave to be preserved. He apparently had no fear of man about him.”[32]

After arriving in Utah, leaders of the Church who had known Patten occasionally spoke with reverence about his martyrdom and his post-mortal commission to preach the gospel—descriptions that may have been omitted for one Joseph had considered a “heel lifter.” The most common pattern when Patten’s name appears in these speeches is to group him with Joseph and Hyrum as the Church’s first martyrs. In such appearances, Patten is seldom the central subject, instead his name—along with Joseph and Hyrum’s—is invoked to illustrate the actions of true believers, worthy of emulation.[33] An example of this rhetoric surrounding Patten’s name can be found in a sermon by Joseph F. Smith. Though Joseph F. Smith narrowly missed overlapping his life with Patten’s by a few weeks, he was undoubtedly shaped by men like Wilford Woodruff who had known Patten in life. Joseph F. Smith remarked in 1882 that Patten, along with Joseph, Hyrum, Brigham, Heber C. Kimball, and Joseph Smith Sr., “took an active part in the establishment of this work, and who died true and faithful to their trust.”[34] The frequent and casual inclusion of Patten’s name alongside Joseph, Hyrum, and the other two who “never lifted their heel” could indicate that in the public statements of those who knew Patten well, he was worthy of the highest honor afforded early Saints.

Woodruff’s praise of the deceased Patten appeared to intensify as he aged. In 1895—nearly sixty years after Patten’s death—Woodruff ardently defended Patten’s overall conduct during the struggles in Kirtland in 1837, stating that despite all the bitterness among Church leaders at that time, “David Patten was not in Kirtland at this time; he was in Missouri. He never apostatized, but died a martyr.”[35] While it would be convenient if Woodruff’s remarks here overrode or completely contradicted what was recollected in 1857, that does not seem to be the case. For example, while Patten was previously in Missouri before returning to Kirtland, he was certainly present in Kirtland for a portion of the difficulties there. The effects of memory over a lifetime can challenge the accuracy of even earnestly felt recollections. That said, Patten was gone on a mission to Canada for the later, more extreme difficulties surrounding the takeover of the Kirtland Temple and the attempted coup d’état by Warren Parrish and others. This absence to Canada may have been what Woodruff was referring to, and he may have simply misremembered that Patten was in Canada instead of Missouri. Regardless, Woodruff’s statement can be taken as an explicit recommendation—in Woodruff’s opinion—of the character and faithfulness of David W. Patten and his commitment to Joseph Smith during the Kirtland period.[36]

Wilford Woodruff’s death in 1898 marked the conclusion of an era where many of those talking about David Patten had known him in life, even if remembering him distantly. The hagiographic remembrance of Patten reached a pinnacle in 1900 with the publishing of Lycurgus Wilson’s biography. It is fascinating that this coincides with the dawn of a new period where those writing about Patten would do so from the written recollections that others, now deceased, had left behind.

The problem in this analysis and near speculation regarding Joseph’s 1843 comment, however, is that regardless of whether Joseph’s remarks were intended to apply to David W. Patten or not, Joseph’s statement is made with thorough boundaries: “Of the first Twelve Apostles chosen in Kirtland and ordained under the hands of Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and myself”—one of whom was undoubtedly David W. Patten—“there have been but two”—and when Joseph has it recorded on the spot as he says it, it’s difficult to say that he meant three or that the remark was mischaracterized during transcription—“but what have lifted their heel against me, namely Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball.” Joseph’s delineation is clear, even if it might lead to questions regarding why he categorized the men he served with in the manner that he did.

Conclusion

Two members of the original Quorum of the Twelve Apostles chosen in 1835 were praised by Joseph Smith, and the “others” were criticized as having “lifted their heel” against him. Of those ten, nine were subjected to church discipline at one time or another, actively criticized the Prophet, and worked against the aims of the Church. Only David W. Patten remains mysterious in his relationship with Joseph and why he may have been included among the “heel lifters.” His inclusion could have been completely intentional on the part of Joseph in reference to difficulties they had with each other in Kirtland in 1837. It is also possible that Joseph was not intending to asperse Patten in his remarks regarding the other original members of the Twelve (Patten being five years deceased at the time). Either way, only two things are certain: First, it is clear that Joseph said what he said and that without him being immediately present to give commentary, his statement must stand as it is. Second, it is also clear that even if David Patten is to be included with the other nine who “lifted their heel,” his life and actions reveal him to be much more like Heber and Brigham than the other Apostles Joseph had implicitly criticized—a sentiment that many of Joseph and Patten’s contemporaries shared.

Lacking in all of this, and worthy of further research and elaboration, would be a historiographical treatment of the way that Patten was discussed and remembered after the death of those who knew him personally. At what point did the tone used to describe Patten’s life begin to shift away from the hagiographic praise of Patten’s unshakable faith in the face of death at the beginning of the twentieth century to his placement among those “who lifted their heel” against the Prophet at the beginning of the twenty-first? Whatever the case, it is clear that by Joseph Fielding Smith’s time as an Apostle in 1947, it had become an issue worthy of comment[37] and that later biographers and historians like Whiting and Esplin would feel necessary to account for and explain. When and how that shift in discourse around Patten took place is worthy of further exploration in a future article.

The persisting uncertainty and new questions surrounding Joseph’s 1843 remark does not render this article and its treatment pointless, however. In the least, this analysis has a few important uses. For this specific thread in Church history, let it serve as an invitation to withdraw from certainty about Joseph’s feelings regarding David W. Patten’s faith and the quality of Patten’s character. Generally, let this treatment be a plea to exercise caution in judgment. There is danger in making quick characterizations and immediate inferences about the character of other people—especially those that lived in the past. Data removed from their originating contexts and effortlessly recombined over a century later easily lend to deceptively simple conclusions. Acknowledging and embracing limber ambiguity—in our lives and in the lives and words of historical figures—can lead us to a more charitable outlook. This charitable patience with each other is the timeless lesson that Paul taught Titus: “To speak evil of no man, to be no brawlers, but gentle, shewing all meekness unto all men. For we ourselves also were sometimes foolish, disobedient, deceived, serving divers lusts and pleasures, living in malice and envy, hateful, and hating one another. But after that the kindness and love of God our Saviour toward man appeared, not by works of righteousness which we have done, but according to his mercy he saved us” (Titus 3:2–5).

Notes

[1] “Introduction to the Kirtland Safety Society,” www.josephsmithpapers.org.

[2] Lawrence R. Flake, Prophets and Apostles of the Last Dispensation (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2001).

[3] Saints: The Story of the Church of Jesus Christ in the Latter Days, vol. 1, The Standard of Truth, 1815–1846 (Church Historian’s Press, 2018), 289–90.

[4] Flake, Prophets and Apostles.

[5] History, 1838–1856, volume D-1 (1 August 1842–1 July 1843), 1563, www.josephsmithpapers.org.

[6] Unless otherwise cited, the material in the table below is drawn from Flake, Prophets and Apostles.

[7] Fred C. Collier, ed., Kirtland Council Minute Book (Collier’s Publishing Co., 2002), 184–86.

[8] Document Containing the Correspondence, Orders &c. in Relation to the Disturbances with the Mormons; And the Evidence Given Before the Hon. Austin A. King, Judge of the Fifth Judicial Circuit of the State of Missouri, at the Court-House in Richmond, in a Criminal Court of Inquiry, Begun November 12, 1838, on the Trial of Joseph Smith, Jr., and Others, for High Treason and Other Crimes Against the State; Fayette, Missouri, 1841, 57, www.josephsmithpapers.org.

[9] Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 332.

[10] Flake, Prophets and Apostles, 26.

[11] History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 (1 September 1834–2 November 1838), October 1835, 631–32, www.josephsmithpapers.org. See also Arnold K. Garr, “Joseph Smith: Man of Forgiveness,” in Susan Easton Black and Charles D. Tate Jr., eds., Joseph Smith: The Prophet, the Man (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1993), 127–36. See also History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 (1 September 1834–2 November 1838), December 1835, 663–65, www.josephsmithpapers.org.

[12] Bushman, Joseph Smith, 337.

[13] Mary Fielding Smith letters to Mercy F. Thompson, 1833–1848, June 1837, Mary Fielding Smith Collection, ca. 1832–1848, Church History Library, MS 2779, p. 7, https://

[14] See B.H. Roberts, The Life of John Taylor (George Q. Cannon & Sons, 1892), 39–40.

[15] History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 (1 September 1834–2 November 1838), 25 October 1838, 840, www.josephsmithpapers.org.

[16] History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 (1 September 1834–2 November 1838), 25 October 1838, 840, www.josephsmithpapers.org.

[17] History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 (1 September 1834–2 November 1838), 25 October 1838, 840, www.josephsmithpapers.org. Joseph’s contrast between Patten and Marsh conveniently provides the timing in which Joseph seems to be reflecting back on Patten’s death. Joseph’s complete aside about Marsh reads as follows: “How different his fate from that of the Apostate Thomas B. Marsh, who this day vented all the lying spleen and malice of his heart towards the work of God in a letter to Brother [Lewis Abbott] and Sister [Ann Marsh] Abbott. To which was annexed an addenda by Orson Hyde.” The letter from Marsh and Hyde to the Abbotts seems to be referring to a letter dated October 25, 1838 (see Letterbook 2, 18, www.josephsmithpapers.org). In the letter, Marsh refers to Joseph as a “very wicked man,” comparing him to the Roman emperor Nero. He further describes Joseph and Sidney Rigdon as disposed in the Missouri conflict to “pillage, rob, plunder assassinate and murder.” In the moment Joseph records his thoughts on the two, the comparison between Marsh and Patten could not be more stark.

[18] History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 (1 September 1834–2 November 1838) [addenda], 27 October 1838, 10, www.josephsmithpapers.org.

[19] Flake, Prophets and Apostles.

[20] History, 1834–1836, 3 November 1835, 117, www.josephsmithpapers.org.

[21] While the speaker is unclear in Wilford Woodruff’s original journal account, he clarified in the draft for his autobiography compiled seven to nine years later. In that manuscript for his autobiography, Woodruff also solidifies the setting—that of the Church Historian’s office rather than President Young’s office. See Autobiography, vol. 3, circa 1865–66, 214, https://

[22] Journal (January 1, 1854–December 31, 1859), June 25, 1857, https://

[23] Journal (January 1, 1854–December 31, 1859), June 25, 1857, https://

[24] Journal (January 1, 1854–December 31, 1859), June 25, 1857, https://

[25] Because Whiting includes details present only in the manuscript of Woodruff’s autobiography, it is likely she is quoting from that source rather than Wilford Woodruff’s journal.

[26] Linda Shelley Whiting, David W. Patten: Apostle and Martyr (Cedar Fort, 2003), 110–11.

[27] This is an adjustment Whiting makes without noting it—perhaps regarding it as a small memory error on the part of whomever was making the recollection that Wilford Woodruff recorded in 1857.

[28] Whiting, David W. Patten, 110.

[29] Whiting, David W. Patten, 110. It is also interesting that Whiting attributes Joseph’s remark to a “talk,” considering that no such context is provided surrounding Joseph’s comment that Bullock recorded as part of Joseph’s history.

[30] Ronald K. Esplin, “Joseph Smith and the Kirtland Crisis of 1837,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet and Seer, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2010), 280–81.

[31] Journal, December 1842–June 1844; Book 2, 10 March 1843–14 July 1843, 28 May 1843, 225, www.josephsmithpapers.org. It is interesting to note that the journal simply mentions that Joseph was “married.” Historians conclude this refers to Joseph Smith Jr. and his sealing to Emma Smith.

[32] Wilford Woodruff, quoted in Lycurgus A. Wilson, Life of David W. Patten: The First Apostolic Martyr (Deseret News, 1900), 70.

[33] See the following talks printed in the Journal of Discourses: Heber C. Kimball (November 25, 1860), 8:62; George A. Smith (July 24, 1852), 1:7; Brigham Young (June 22, 1856), 3:51; George Q. Cannon (May 6, 1866), 11:35; John Taylor (June 24, 1868), 12:39; Orson Pratt (October 5, 1877), 19:20; and Franklin D. Richards (May 17, 1884), 25:28. All spoke of Patten’s place alongside Joseph and Hyrum. Orson Pratt further assumed that because Patten had died in the faith and was accepted by the Lord, he would hold the keys of the presidency of the Quorum of the Twelve in the next world in place of the fallen Thomas B. Marsh (see Orson Pratt, in Journal of Discourses, 19:20).

[34] Joseph F. Smith, in Journal of Discourses, 22:352.

[35] “Discourse by President Wilford Woodruff,” Millennial Star, May 30, 1895, 340.

[36] Wilford Woodruff was not the only one who felt this way. Like Woodruff, Heber C. Kimball named his sons after David Patten to honor his service, faith, and sacrifice.

[37] Joseph Fielding Smith (while serving as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve and having previously served as Church Historian) directly addressed Joseph’s 1843 statement regarding the Apostles and its implications for David Patten. He stated his opinion that “David W. Patten never came under condemnation by the Prophet Joseph when he said all the original twelve had raised the heel against him save Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball. Patten was dead and had never lifted [his] heel against the Prophet Joseph.” (Florida Stake Quarterly Conference, Sunday, May 18, 1947, in notes recorded by stake patriarch James R. Boone as President Smith spoke, shared from a collection of notes in the possession of his son David F. Boone [BYU Church History and Doctrine faculty]).

Joseph Fielding Smith’s expressed opinion on this matter does not necessarily prove Joseph Smith Jr.’s intentions in 1843, but it does demonstrate that this question had become insistent enough in Latter-day Saint discourse to be commented on in a conference of the Church in Florida some forty-seven years after Wilson’s hagiographic telling of Patten’s story.