Joe Cochran, "'An House of Prayer for All People': A Guide to Christ’s Cleansing of the Temple," Religious Educator 25, no. 2 (2024): 93–114.

Joe Cochran (joe_cochran@byu.edu) is an adjunct professor in Religious Education at Brigham Young University.

If Christ exemplified love in all that he did, where then is that love amid a scene of fleeing animals and angry vendors? Jesus Cleansing the Temple (detail), Carl Bloch.

If Christ exemplified love in all that he did, where then is that love amid a scene of fleeing animals and angry vendors? Jesus Cleansing the Temple (detail), Carl Bloch.

Abstract: This article explores the contextual background of Christ’s cleansing of the temple as recorded in the four Gospels. An analysis of scriptural and historical evidence can help teachers and learners better understand what Christ cleansed and for whom his actions were undertaken. Discovering specific meaning and purpose behind the Savior’s words and actions in the temple helps establish this event as yet another witness of the loving, compassionate, and justice-seeking Savior we all know well.

Keywords: Jesus Christ, Temples, Scriptures, Teaching the Gospel

“Is this the same Jesus?” The question has been posed often by students as we’ve considered the story of Jesus Christ cleansing the temple. How could this Jesus who brandishes a whip and flips over tables be the same Jesus who softly comforts the woman caught in adultery, offering a chance to start anew? If Christ exemplified love in all that he did, where then is that love amid a scene of fleeing animals and angry vendors? Without a full understanding of the context of this event and Christ’s actions, one could characterize this story incorrectly.

Through scriptural analysis and drawing on gospel scholarship and the teachings of Church leaders, this study seeks to support religious educators as they prepare to teach this story. The material that follows has been organized into guiding questions that teachers and students alike can use as they explore the story of Christ cleansing the temple:

- Why an animal market and money-changing booths on the Temple Mount?

- What actually happened?

- Was Jesus out of control?

- How does Jesus’s quoting of Jeremiah and Isaiah help explain his actions?

- On whose behalf was the temple cleansed?

In our contemporary religious landscape, we see too often that when God commands something of his followers, it is viewed as contrary to the loving nature of God. Stories like Jesus’s cleansing of the temple could raise concern among students of the gospel if they don’t yet realize that God’s commandments and demands are always a sign of his love. Though we may not fully understand his ways (Isaiah 55:8–9), we can be assured that God “doeth not anything save it be for the benefit of the world” (2 Nephi 26:24). This is true of the Savior’s actions at the temple as well. Reviewing the aforementioned contextual issues behind this event can help students to not only understand the account but also see that “same Jesus” who is full of love and compassion.

Why an Animal Market and Money-Changing Booths on the Temple Mount?

The synoptic Gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—each describe the cleansing of the temple during the final week of the Savior’s mortal ministry. There is some disagreement about the day of the event, however, since Matthew and Luke place it on Palm Sunday after the triumphal entry while Mark places it on the following day (“on the morrow,” Mark 11:12). On the other hand, John situates the cleansing at the beginning of Christ’s ministry. It is possible that Jesus cleansed the temple twice during his ministry.[1] Either way, in each recounting, Jesus is visiting Jerusalem to celebrate Passover.

Each spring, the population of Jerusalem swelled as hundreds of thousands of Jews observed Passover. Since the Josian reforms (2 Kings 23), the Passover celebration had shifted away from a family affair to a centralized community celebration held at the Jerusalem temple (Deuteronomy 16:6–7; 2 Chronicles 35:1–19). Rather than sacrificing a lamb or goat at home, the people were required to bring those animals to the temple. Numerous pilgrims took advantage of this temple visit to also sacrifice doves for sin and guilt offerings. While some families brought their own animals for sacrifice, many purchased the animals in or near Jerusalem. This could have been due to the risk of an animal being injured or sullied and thus declared blemished or unworthy of sacrifice. Thus, a demand existed for animals that had been declared unblemished by temple priests to be located as close to the temple as possible.[2]

Another reason many visited the temple during this time was to pay the annual temple tax of half a shekel per male over the age of twenty.[3] The temple priests required that payment specifically be made in the Tyrian shekel[4] rather than in coinage from each person’s country.[5] For example, while the Roman denarius would be used to pay for Roman taxes,[6] Galileans would need to exchange their denarii for the Tyrian shekel before paying the temple tax.[7] The requirement to provide an animal for these sacrifices and pay the temple tax in Tyrian shekels set the stage for a market wherein animals could be purchased and money could be exchanged.[8]

Archaeological findings demonstrate that Herod the Great placed shops and places designed for these business exchanges below the temple courtyard during the reconstruction.[9] By the time of Jesus’s ministry, some of this business had moved up onto the temple platform. Some scholars argue that the temple market was introduced by Caiaphas, the chief priest during Jesus’s ministry, to ensure nothing happened to the animal between Hanuth, the former market site, and the temple.[10] Socially, there is some speculation that the market was created to compete with the already-established market run by the Pharisees on the Mount of the Olives.[11] Merchants rented out space for their stalls and shops within the Court of the Gentiles, helping worshippers to ensure correct coinage and animals, while also probably financially benefiting the temple stewards.[12]

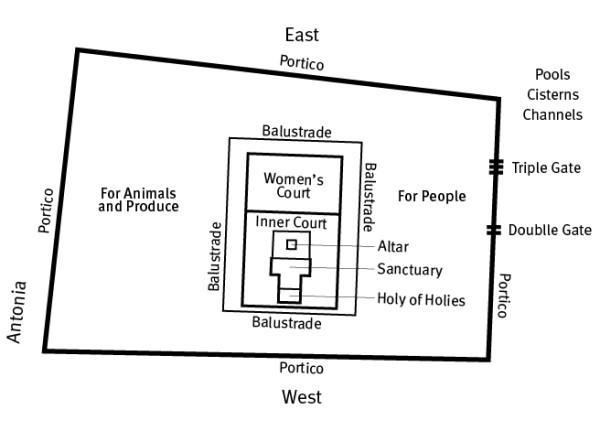

The temple platform consisted of various areas or courts that worshippers would pass through as they moved closer to the sanctuary that housed God’s presence.[13] The Priest’s Court (the innermost court) was reserved for the Levitical priests as they performed their temple duties. Moving outward, the Court of Israel was mostly limited to clean and purified Jewish males.[14] The next area, often referred to as the Court of Women, was open to all Jews that were not declared impure through the law of Moses.[15] Finally, the outermost court, or the Court of the Gentiles, was open to any Jew and Gentile, save for menstruating women,[16] that desired entry.[17]

Figure 1. Map of the temple platform. Adapted with permission. Bruce Chilton, The Temple of Jesus (1992).

Figure 1. Map of the temple platform. Adapted with permission. Bruce Chilton, The Temple of Jesus (1992).

Covering thirty-six acres, or the equivalent of about twenty-eight football fields,[18] the temple grounds might have comfortably hosted around one hundred thousand people at any given time.[19] As illustrated in figure 1,[20] the outermost court, or the Court of the Gentiles, is likely where these markets were located.[21] The Court of the Gentiles surrounded the temple proper and could be divided into north and south sides:

On the north side, the pure, sacrificial animals were slain and butchered, and stone pillars and tables, and chains and rings and ropes, and vessels and bushels, were arranged to enable the process to go on smoothly, and with visible, deliberate rectitude. The north side of the sanctuary, then, was essentially devoted to the preparation of what could be offered, under the ministration of those who were charged with the offering itself. The south side was the most readily accessible area in the temple. . . . [The] elaborate system of pools, cisterns, and conduits to the south of the mount, visible today, evidences the practice of ritual purity, probably by all entrants, whether Jewish or Gentile, into the temple. Basically, then, the south side of the outer court was devoted to people, and the north side to things.[22]

It is likely, then, that these markets were located within the southern side while the northern side would have been heavily occupied by tens or even hundreds of thousands of animals brought in for sacrifice during a festival season.[23]

With the above context, we can imagine the scene that met Jesus’s eyes as he entered the Court of the Gentiles during the Passover festivities. The bustling courtyard would be packed by hundreds, if not thousands, of people bringing animals to be inspected for sacrifice, coming to pay their annual tax, or simply coming to learn from rabbinic teachers who, like Jesus often did, spent time teaching and learning within the temple (Matthew 21:23; Luke 2:41–51; John 7:14).[24] Amid the hustle of people, the bleating and cries of animals along with the shouts of shopkeepers vying for business created a cacophony of noises. Finally, an unknown, but obviously noticeable, number of people passed through the temple, often carrying vessels.[25] All these images and sounds might help the reader better understand Jesus’s lament that the temple had become “an house of merchandise” (John 2:16).

What Actually Happened?

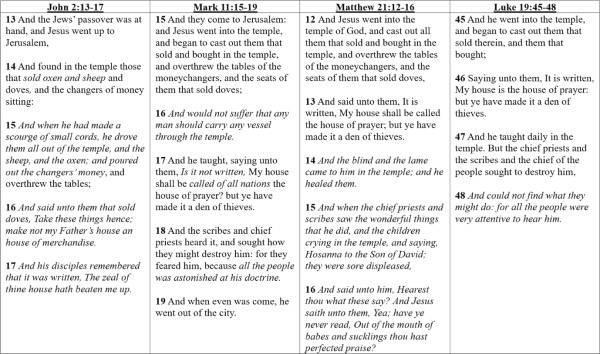

In the following section we will explore what the Gospel accounts teach about this episode. One noticeable difference, discussed above, is the timing of when it occurred in the Savior’s life. Rather than establish whether Jesus cleansed the temple multiple times or speculate about which Gospel author correctly dated the event, the purpose of this article is to help readers better understand what happened during the cleansing of the temple and the possible motivations behind the Lord’s actions and words.[26] Table 1 is a side-by-side comparison of the cleansing of the temple pericope, with unique details of each author in italics.

In each account, the story begins with Jesus entering the temple and witnessing the sights and sounds of the market amid the busy traffic caused by pilgrims and temple worshippers. He takes in the tables of the money changers, the doves and their sellers, and, in John’s account, the oxen and sheep that had also been brought in specifically for the Passover celebration (2:14). John’s inclusion of those larger animals is coupled with the unique detail that, upon seeing the scene, Jesus made a scourge of small cords—likely with the intent of driving out the oxen and sheep from the temple courtyard (v. 15).

Table 1. Comparison of Gospel accounts of Jesus cleansing the temple. Unique details from each account are italicized.

Table 1. Comparison of Gospel accounts of Jesus cleansing the temple. Unique details from each account are italicized.

Matthew, Mark, and John describe Jesus overthrowing the tables of the money changers, with John’s addition that Christ “poured out the changers’ money” (John 2:15). Next, each synoptic author highlights that Christ cast out “them that sold and bought in the temple,” meaning that his actions were not only affecting the market but also those who were actively using the market at the time of Christ’s arrival (Matthew 21:12; Mark 11:15; Luke 19:45). Matthew’s and Mark’s accounts follow with Christ overturning the seats of those who sold doves, and John wrote down Christ’s specific commandment that they “take these things hence; make not my Father’s house an house of merchandise” (John 2:16).

It appears that the commotion of the cleansing was not enough to discourage the foot traffic of those using the courtyard as a thoroughfare, for Mark’s account uniquely adds that Jesus “would not suffer that any man should carry any vessel through the temple” (Mark 11:16).[27] At the end of the cleansing, the synoptic accounts share that the Savior, quoting Isaiah (56:7), taught the witnesses of the scene that rather than his house being a house of prayer, it had become a den of thieves. After this declaration, Matthew informs readers that “the blind and the lame came to him in the temple; and he healed them” (Matthew 21:14), with Mark and Luke implying that Christ stayed at the temple to teach (Mark 11:19; Luke 19:47).

In each account we learn that the chief priests and scribes witnessed the scene or at least the aftermath. John does not record that the chief priests were concerned with Christ’s actions, but rather focused on whether he has the authority to do so. Matthew’s account portrays an upset group of leaders who express sore displeasure at “the wonderful things that [Jesus] did” and the shouts of “Hosanna to the Son of David” that had begun anew, echoing the triumphal entry (Matthew 21:15–16). Subsequently, Mark and Luke describe this group of Jewish leaders, who fear Jesus (Mark 11:18; Luke 19:47), as seeking “how they might destroy him” but being inhibited by the large groups of people that were present to hear his teachings.

Was Jesus out of Control?

The vivid imagery of Jesus overturning the tables, dumping out the coins, and wielding a whip to drive animals out of the courtyard visually stands in great contrast to tender moments such as Christ personally ministering to the outcast or lovingly taking children into his arms and blessing them. Did he lose his composure? How can we reconcile this event with the same Savior that, according to John’s account (11:35), wept with Martha and Mary outside Lazarus’s tomb? The scriptural accounts provide ample details that allow us to seek answers to these questions.

Let’s first consider John’s account. Jesus witnessed the scene and made a scourge of small cords. Rather than act in the moment, Jesus deliberately halted, recognizing the difficulty of moving great numbers of large animals without a tool of the trade. His creation of the scourge likely required some gathering of cords from his disciples or the area nearby—again signifying a deliberate approach to the cleansing rather than an instinctive reaction.

John’s account also shows that Jesus was careful around the helpless and smaller encaged doves. One commentator noted: “Men, sheep, and oxen could be driven, pushed or whipped without harm; but to throw down, scatter, or hit harmless doves with a whip would cause great harm to these defenseless birds. Notice Jesus’ perfect control as he approached those who sold doves, saying, ‘Take these things hence’ (John 2:16). He was not out of control, even in this dramatic physical act.”[28] Rather than throw down or assault the cages, Christ displayed “tender regard for the imprisoned and helpless birds,” reflecting a deliberate and thoughtful approach to his task.[29]

The synoptic Gospels place this story within the narrative of Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem and with the accompanying imagery of a Davidic king entering the temple to claim his throne. Considering that Matthew’s and Luke’s accounts portray the scene as following almost immediately after the procession, one could imagine there were hundreds if not thousands of witnesses of the scene.[30] Yet there is no account or witness decrying Christ as abusive or uncontrolled in his actions. Reflecting on this event, President Gordon B. Hinckley described Christ’s words as “spoken more as a rebuke than as an outburst of uncontrolled anger.”[31] Elder James E. Talmage furthers that argument by highlighting that, in Matthew’s account, the cleansing was “followed by a calmness of gentle ministry; there in the cleared courts of His house, blind and lame folk came limping and groping about Him, and He healed them.”[32]

Perhaps the greatest evidence of Christ’s control during this scene is the fact that the Jewish leadership did not arrest him at that moment. Bearing in mind that Jesus, through many of his teachings and actions, had already challenged the status quo, it would be easy for the leadership to order the temple guard to arrest him on the spot. Also, “that his actions were fully justified seems clear from the fact that he was not challenged to stop or asked why he had done what he did.”[33] Possibly self-convicted of being exposed for not fulfilling their own duty to uphold the sanctity of the temple, the Jewish leaders questioned Jesus’s authority[34] rather than debated the necessity of his actions.[35] No temple soldiers were called to the scene to quell a potential uproar, nor did Roman centurions interfere.[36]

How Does Jesus’s Quoting of Jeremiah and Isaiah Help Explain His Actions?

The synoptic Gospels contain the rebuke given by Jesus when he cleansed the temple: “My house shall be called the house of prayer; but ye have made it a den of thieves” (Matthew 21:13). Despite the selling of animals and exchange of coins as necessary for the function of the temple, the issue might not have been with the practice but rather with the location. One scholar wrote that “[Jesus] took offence at the place where the action was happening. It was a sanctity issue. The actions themselves, except to the extent they may have been taken advantage of the poor, could be practiced elsewhere.”[37] Places for each of these tasks existed elsewhere[38] and distracted from the true purpose of the temple wherein man could, through worship and sacrifice, learn of God’s ways and “walk in his paths” (Isaiah 2:3).

Further, Jesus’s use of the word thieves echoed the prophet Jeremiah’s similar use of the word robber for those who hypocritically worshipped in the temple: “Is this house, which is called by my name, become a den of robbers in your eyes?” (Jeremiah 7:11). By reiterating Jeremiah’s words, Jesus reminded his listeners that there is danger in “ritual without accompanying repentance and good deeds.”[39] Accordingly, Christ’s words signaled that participation in the covenants and ordinances of the temple are outward practices that should be centered on inward spirituality.[40]

To what outward practices was Jesus referring in his rebuke? The priests and scribes, who were masters of the law, likely recognized in Jesus’s reference other words spoken by Jeremiah, such as “oppress not the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow” (Jeremiah 7:6). The following day, Jesus reiterated Jeremiah’s warning as he decried the hypocrisy of these leaders while he taught in the temple:[41] “But woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye shut up the kingdom of heaven against men: for ye neither go in yourselves, neither suffer ye them that are entering to go in. Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye devour widows’ houses, and for a pretence make long prayer: therefore ye shall receive the greater damnation” (Matthew 23:13–14). Again, we see the Savior emphasizing private treatment of others as a true reflection of worship rather than the public appearance of righteousness.[42] Later in this discourse, Jesus lamented that these leaders had “omitted the weightier matters of the law, judgment, mercy, and faith” (v. 23).

At the heart of the temple leadership stood Ananias, the former high priest, and his son-in-law, Caiaphas, the current high priest. Josephus described Ananias as increasing “in glory every day, and this to a great degree, and [having] obtained the favor and esteem of the citizens in a signal manner; for he was a great hoarder up of money.”[43] Though the introduction of the temple market was attributed to Caiaphas,[44] scriptural evidence points to Ananias as still holding great sway over the Sanhedrin and Jewish leadership (John 18:13–24).[45] Perhaps to the Savior the sights and sounds of the temple no longer solely represented a people’s willingness to worship their God, but rather constituted the hypocrisy and greediness of leaders who exploited their fellow man.[46]

If Christ’s quotation of Jeremiah was intended as a specific message to Jewish leadership, why did he upend the moneychangers’ tables and drive out the animals from the courtyard? Not themselves entirely innocent, these moneychangers and animal sellers were likely taking advantage of the pilgrims and worshippers at the temple. Many historical sources[47] relate stories of vendors who, probably in response to the high rental fees they paid to sell within the temple, demanded exorbitant prices for their goods.[48] For example, one record states that the price of a pair of doves had increased to one gold dinar, which equates to twenty-five times the normal price, in response to increased demand for doves.[49] While the practice of adjusting price to reflect supply and demand is economically sound, the point of offering doves as an acceptable sacrifice was to lessen the financial cost for the poor, not increase it (Leviticus 1:14–17; 5:7; 12:8).[50]

One can only imagine the chaos that ensued after the scene when the vendors and money changers confronted their landlords after the cleansing! Were they allowed to reestablish their businesses within the Court of the Gentiles? If not, where would they sell now? It is likely that other vendors snatched up the previously used premises below the Temple Mount or elsewhere, so where would the ejected vendors go? What about the rent they had paid? Would the temple leadership honor their contracts? Was increased scrutiny placed on the legality and morality of the markets? In a matter of a few moments, Jesus publicly exposed the hypocrisy and exploitation of the markets while also challenging the authority of those who allowed it.[51] It cannot be too surprising, then, that the synoptic Gospels first report of the Jewish leadership’s desire to kill Jesus after this event (Matthew 21:46; Mark 11:18; Luke 19:47).

Another reason behind the cleansing is found in Christ’s quoting of Isaiah in calling the temple “an house of prayer”:

Even them will I bring to my holy mountain, and make them joyful in my house of prayer: their burnt offerings and their sacrifices shall be accepted upon mine altar; for mine house shall be called an house of prayer for all people. The Lord God which gathereth the outcasts of Israel saith, Yet will I gather others to him, beside those that are gathered unto him. (Isaiah 56:7–8)

Sometimes lost in the imagery of the cleansing and our desire to understand why Christ acted in such a manner is a precious insight given in Matthew’s account: “And the blind and the lame came to him in the temple; and he healed them” (Matthew 21:14). Why would Matthew pause his narrative of the event to specifically highlight the entrance of the blind and the lame into the temple unless they were not within that portion of the temple before the cleansing?[52] Perhaps Matthew is trying to remind the reader that the story might also be about whom the temple was cleansed for.

On Whose Behalf Was the Temple Cleansed?

If we recall the layout of the Temple Mount, the inner sanctuary—meaning the area that contained the Court of Women, Court of Israel, and the Court of Priests—was reserved for purified Israelite worshippers. Those who were deemed impure were allowed into the Court of the Gentiles, or the outermost court, but no farther.

Archaeologists have found tablets in Jerusalem that warn in Greek and Latin, “No alien may enter within the balustrade around the sanctuary and the enclosure. Whoever is caught, on himself shall he put blame for the death which will ensue.”[53] For example, the very trial that sent Paul before Herod Agrippa II and eventually led him to Rome stemmed from accusations from the Jews in the temple that he had brought Gentiles into the inner sanctuary. Paul was saved from the angry mob’s beatings only when a Roman chief captain arrived with centurions to discover the cause of the uproar (Acts 21). Paul’s rescue might have been the exception, though, since Josephus wrote that fervor about keeping Gentiles out of the temple eventually reached such a peak that the Romans would allow Jews to execute any Gentiles that entered the inner sanctuary.[54]

Being foreign was not the only attribute that could lead to one’s exclusion from worship within certain areas of the temple. No one born with or afflicted by a serious physical defect was allowed beyond the Court of the Gentiles.[55] In particular, “blindness and lameness constituting a ritual (cultic) blemish, their exclusion stemmed from fear of polluting the house of the Lord.”[56] The blind and the lame leaving their normal quarters to move within the inner sanctuary caused quite the stir. Scholars have debated multiple possible reasons for this exclusion. Some believe it could have stemmed from King David’s reaction to the Jebusite taunting that even their blind and lame could keep out David and his army.[57] Before beginning the attack on Jerusalem, David vowed that “whosoever getteth up to the gutter, and smiteth the Jebusites, and the lame and the blind, that are hated of David’s soul, he shall be chief and captain.” From that point on, a common phrase among Israelites was “the blind and the lame shall not come into the house” (2 Samuel 5:6–9).[58] Others point to the exclusion being an extension of the strict requirements for Levitical priests that perform services within the temple (Leviticus 21). Under this argument, both the offering and the offerer had to be without blemish to be acceptable to the Lord. After presenting this argument, one scholar wrote that “physically disabled people had no business whatsoever to even enter the temple.”[59]

An example of physical impairment affecting one’s worthiness to enter further into the sacred temple precincts is found in Acts 3, where Peter and John heal a man who had been lame from birth. Before the healing, the man had been “laid daily at the gate of the temple which is called Beautiful, to ask alms of them that entered into the temple” (v. 2). As Peter and John passed by him heading toward the inner sanctuary,[60] he asked for alms, leading to an interaction that resulted in his healing. After rejoicing in the newfound strength in his legs, the man joined Peter and John as they left the Court of the Gentiles and passed into the inner sanctuary (v. 8).[61]

It is noteworthy that no one is concerned with the man’s presence within the inner sanctuary. While most, if not all, recognized him from his days as a lame beggar, now they could clearly see a fully healed man walking, leaping, and rejoicing within the temple complex. Since the disability had clearly been removed, the man was no longer societally viewed as impure.

Returning to our original story, contrast this healed man’s entrance into the inner sanctuary with the scene of unhealed blind and lame men and women entering the inner sanctuary to be with Jesus after the cleansing. One scholar offered this comment:

Already the religious leaders were not happy with Jesus because of the cleansing of the temple and the events preceding it. Now the thing that was not done was happening: the blind and lame who were previously excluded, came in, and Jesus approved it. He went further: He healed them. For the religious leaders, the temple has been defiled by the entrance of those who did not have the right to enter it. Their cups overflowed. They were full of indignation (Matt 21:15). The condemnation of Jesus was just steps away.[62]

Having cleared out the temple grounds, Christ then welcomed those who otherwise had been excluded by temple leadership, another public demonstration of his authority.

By cleansing the temple, Jesus asserted his authority, demostrating that he is greater than the temple. This could serve as an analogy that he can—like he did with the temple—make us clean again. Expulsion of the Money Changers from the Temple, Luca Giordano.

By cleansing the temple, Jesus asserted his authority, demostrating that he is greater than the temple. This could serve as an analogy that he can—like he did with the temple—make us clean again. Expulsion of the Money Changers from the Temple, Luca Giordano.

This moment could be viewed as a microcosm of Christ’s upcoming fulfillment of the law of the Moses. Jesus showed “his authority to create purity in all those desiring to worship God, demonstrating that as the One who is greater than the temple, he fulfills the Old Testament prescriptions for cleansing that the temple practices required to come into the presence of God.”[63] In addition, “the temple incident is not just preparation for the coming of the kingdom. It is an enactment of the kingdom.”[64] By restoring the excluded ones to full participation in the worship community,[65] Christ signaled that “He himself takes to make the worshiper fit for worship.”[66] Rather than needing to offer sacrifices to claim purity, Jesus is the Purifier for any who approach him with a broken heart and a contrite spirit (3 Nephi 9:19–20).

Is This the Same Jesus?

The final insight into why Jesus cleansed the temple is given at the conclusion of John’s account of the cleansing: “And his disciples remembered that it was written, The zeal of thine house hath eaten me up” (John 2:17). While the specific quoted verse is Psalm 69:9,[67] the entire psalm recounts just how different David was viewed by his contemporaries because of his enthusiasm for God and his unfulfilled zeal for building a sanctuary or temple for his God. By referencing this specific psalm, John illustrated that Jesus was also set apart from his peers owing to his enthusiastic love of God and his desire to create a sanctuary for the worship of his Father. Indeed, one of the repeated emphases in the Gospel of John is Jesus’s zeal for doing the will of his Father. Jesus taught that he has been sent by the Father (John 3:16; 5:36; 8:16; 17:3), that he and the Father are one in purpose and action (John 5:17–23; 14:6–11; 15:23–24; 17:21), that his work is to glorify the Father (John 15:8; 17:1), and that his life is dedicated to doing the Father’s will (John 5:30; 8:29; 10:15–18; 14:31; 15:10).[68] Because the holy temple is the gateway to the greatest blessings from God,[69] and because it is the Father’s will that his children receive all that he has (Luke 12:32; Doctrine and Covenants 84:38), Jesus needed to restore the temple’s purpose of enabling communion with God in his dwelling place (Exodus 29:46).

Indeed, this second tie to David’s psalm, being Christ’s determination to ensure that the temple was a sanctuary for worship, is at the heart of this story. Those who cared for the sacred building had turned the Father’s house into a den of thieves, and Christ, acting for the Father, had come home to cleanse and chastise. Like everything Christ did, the cleansing of the temple stemmed from his love for his people, “for whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth” (Hebrews 12:6). Now, having reproved his people with sharpness (Doctrine and Covenants 121:43), Christ showed forth an increase of love toward the temple worshippers by making the house of God open to all Israel, be they healthy, sick, rich, or poor.[70] Those who had long awaited their chance to be healed and to worship in his Father’s house could now enter and commune with Jehovah himself. Though thousands of Jews had ignored or avoided confronting these corrupt practices, Christ’s zeal for the sanctity of his Father’s house and his love for Israel compelled him to do what others would not.

One can only imagine the joy expressed by these men and women who finally found themselves within the inner sanctuary as they, with the multitudes of onlookers, proclaimed, “Hosanna to the Son of David.” They had personally witnessed the overdue cleansing of the temple and restoration of the “outcasts of Israel” (Isaiah 56:8) by the true High Priest (Hebrews 2:17; 4:14). As the temple leadership quaked with indignation, Jesus Christ, at least for the moment, enjoyed this “perfected praise” (Matthew 21:16), for the Jerusalem temple was once again “a house of prayer” (Isaiah 56:7) for all who came to worship his Father. Yes, we can be reassured that this is the same Jesus—he who defended the outcast, spoke out against unrighteous leadership, zealously obeyed his Father, and lovingly ensured that all of God’s children could joyfully worship in the holy temple.

Notes

[1] In John’s account, the crowd’s interest in Christ’s authority rather than his actions hints at their recognition that the cleansing served not only as a functional necessity but also as a symbolic statement: “By going to the Jerusalem temple and disrupting the practices that were necessary for the celebration of Passover, Jesus places himself in a long line of Israel’s prophets who go to Jerusalem, the center of religious and political power, and announce and enact the word of God. Jeremiah, for example, repeatedly stood in the gates and outer courtyard of the temple (where Jesus is in the Gospel of John) and speaks a disruptive word of God (for example, Jer. 7:1–8:3 or Jer. 26) or undertakes a symbolic act (the broken pot of Jer. 19:1–15) to demonstrate the word of God. Jesus follows in the tradition of Jeremiah, boldly proclaiming and enacting the word of God in Jerusalem. Those in the temple who saw what Jesus had done asked, ‘What sign can you show us for doing this?’ (John 2:18). Their question shows that they recognized that in his actions in the temple, Jesus was claiming the role of prophet” (Gail O’Day, “The Cleansing (or Cursing?) of the Temple,” Bible Odyssey, https://

[2] “Despite all that we do not know, the point is obvious that the temple required money changers and the purchase of sacrificial animals. People had only two options: they could bring animals from their homes, which was not easy and carried the risk that the animal might be rejected, or they could acquire an animal at the temple or on the Mount of Olives.” Klyne R. Snodgrass, “The Temple Incident,” in Key Events in the Life of the Historical Jesus, ed. Darrell L. Bock and Robert L. Webb (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2010), 447–48; emphasis in original.

[3] James F. McGrath, “Jesus and the Money Changers (John 2:13–16),” Bible Odyssey, https://

[4] Though not explored in this article, there is an argument that the Tyrian coin portrayed an image of Melqart-Herakles, a Phoenician deity, which contradicted the commandment to not have any graven images (Exodus 20:3, 4; Deuteronomy 4:16–18; 5:8). “The rabbis decided that the commandment to give the half-shekel Temple tax, with its proper weight and purity, was more important than the prohibition of who or what image was on the coin.”

Gordon Franz, “The Tyrian Shekel and the Temple of Jerusalem,” Bible and Spade 15, no. 4 (Fall 2002): 113.

For more information, see Peter Richardson, Building Jewish in the Roman East (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2004), 92; and Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, “Jesus and the Money Changers (Mark 11:15–17; John 2:13–17),” Revue Biblique 107, no. 1 (2000): 42–55.

[5] Franz, “Tyrian Shekel and the Temple of Jerusalem,” 113.

[6] The denarius is perhaps most notably used in the story where Jesus is asked about paying Roman taxes. Upon seeing the denarius, Jesus replied, “Render . . . unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and unto God the things that are God’s” (Matthew 22:21; Mark 12:17; Luke 20:25).

[7] Nanci DeBloois, “Coins in the New Testament,” BYU Studies 36, no. 3 (1996): 239–51.

[8] McGrath, “Jesus and the Money Changers (John 2:13–16).”

[9] Eric D. Huntsman, “Cleansing the Temple,” Messiah: Behold the Lamb of God, BYUtv series, https://

[10] Bruce Chilton, The Temple of Jesus: His Sacrificial Program within a Cultural History of Sacrifice (University Park: Penn State University Press, 1992), 107–11. See also Craig A. Evans, Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 355; and Hans D. Betz, “Jesus and the Purity of the Temple (Mark 11:15–18): A Comparative Religion Approach,” Journal of Biblical Literature 116 (1997): 461–67.

[11] Victor Eppstein, “The Historicity of the Gospel Account of the Cleansing of the Temple,” Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft 55, no. 1 (1964): 42–58

[12] Evans, Jesus and His Contemporaries, 319–44.

[13] Chilton, Temple of Jesus, 103–4.

[14] It is important to note that women could pass through this court as they offered sacrifices. “If, for instance, a woman offered a wave offering such as first fruits, she approached the Altar, waved the offering, and placed it beside the Altar.” Shmuel Safrai, “The Place of Women in First-Century Synagogues,” Jerusalem Perspective 40 (September/

[15] Michael Morales explored the relationship between physical status and purity: “Various conditions such as skin diseases make Israelites unclean because it brings them into the realm of death. When Miriam became leprous, Aaron prayed, ‘Please do not let her be as one dead, whose flesh is half consumed . . .’ (Num. 12:12). The leper pronounced unclean, therefore, is required to go into mourning, dishevelling his hair, rending his clothes and being exiled outside the camp of Israel (Lev. 13:45–46)—in essence, such a person ‘experienced a living death.’ Many of the discharges of bodily fluids (such as blood or semen), along with the womb shortly after childbirth, may be correlated with loss of life, rendering one unfit to be in the Presence of fullness of life. Because the wilderness represents chaos and death, Sheol, all that severely smacks of death is driven into the wilderness and away from the Presence of God” (158). Further, “physical imperfection, disruptions, deformities and maladies, though not considered sinful in themselves, nevertheless still reflect sin’s damage and pollution of the earth, and therefore require ritual cleansing” (161). L. Michael Morales, Who Shall Ascend the Mountain of the Lord?: A Biblical Theology of the Book of Leviticus (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2015), 145–84.

[16] Leviticus 15 explains that a menstruating woman is considered unclean and must wait seven days after the menstruation concludes before she can return to the tabernacle/

[17] The cleansing of the temple and Jesus’s subsequent teaching is but one example of his willingness to preach in all parts of the temple. His encounter with and teaching of some of the Jewish leadership during the Feast of the Dedication occurred in Solomon’s Porch, located along the east portico of the Court of the Gentiles (John 10:23–39). His observation and praise of the widow’s mite took place near the treasury located within the Court of Women (Mark 12:41). The Master of the House of Prayer for all people ensured that his word could be heard by all who ascended to the mountain of the Lord (Psalm 24:3): Jews, Gentiles, men, and women.

[18] Gabriel Barkey and Dvira Zachi, “Relics in Rubble: The Temple Mount Sifting Project,” Biblical Archaeology Review 42, no. 6 (2016): 44–55.

[19] Assuming 75 percent of the surface area was usable, and comparing land usage to similar events such as Barack Obama’s inauguration, Mecca, and the Vatican, this author estimates that 100,000 could be comfortably hosted, with a capacity of 250,000 if the crowds stood shoulder to shoulder. See “Jerusalem and the Temple Mount,” Biblical Prospector, January 2, 2010, https://

[20] Chilton, Temple of Jesus, 105, fig. 1.

[21] Chilton, Temple of Jesus, 107; and Nylund, “Court of the Gentiles.” Some scholars suggest that the area under the Royal Portico, located on the north side as well, is where the animals were stabled: Snodgrass, “Temple Incident,” 452; Kim Huat Tan, The Zion Traditions and Aims of Jesus, Society for New Testament Studies 91 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

[22] Chilton, Temple of Jesus, 106.

[23] Josephus, Jewish War 4.9.3.

[24] David Rolph Seely, “The Temple of Herod,” in New Testament History, Culture, and Society: A Background to the Texts of the New Testament, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2019), 53–70.

[25] It is unknown what Jesus was referring to when he prohibited the carrying of vessels. Snodgrass noted that the Greek word σκεῦος, used here for “vessels,” “can be used of an object, a thing, or property as well as a container.”

“Temple Incident,” 447.

[26] It is important to recognize that Markan tradition holds that Matthew and Luke both used Mark’s account as reference for their own texts. Even so, each author differs in his retelling, leading to my decision to discuss the details of the story by referring to each Gospel author rather than doing a Markan and Johannine comparison.

Furthermore, Snodgrass argues that Matthew’s account has “independent tradition,” suggesting there is “a good chance that we have at least three different traditions of the temple incident, that of Matthew, that of Mark, and that of John.” “Temple Incident,” 444.

[27] James E. Talmage hypothesized that the people may have been using the temple platform as a throughfare on their way to business and personal affairs. Jesus the Christ (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1916), 528.

[28] Thomas S. Mumford, “Jesus Begins His Ministry,” A Symposium on the New Testament (Salt Lake City: Church Educational System, 1984), 12 (symposium held on August 15–17, 1984, at Brigham Young University, Provo, UT).

[29] James E. Talmage, Jesus the Christ (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1916), 528.

[30] Mark’s time line differs in that he writes that Jesus went back to Bethany for the night before returning to cleanse the temple the next day.

[31] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Slow to Anger” (general conference talk, October 2007), www.churchof jesuschrist.org.

[32] Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 528.

[33] Mumford, “Jesus Begins His Ministry,” 12.

[34] O’Day, “Cleansing (or Cursing?) of the Temple.”

[35] “The Jews, by which term we mean the priestly officials and rulers of the people, dared not protest this vigorous action on the ground of unrighteousness; they, learned in the law, stood self-convicted of corruption, avarice, and of personal responsibility for the temple’s defilement. That the sacred premises were in sore need of a cleansing they all knew; the one point upon which they dared to question the Cleanser was as to why He should thus take to Himself the doing of what was their duty. They practically submitted to His sweeping intervention, as that of one whose possible investiture of authority they might be yet compelled to acknowledge.” Talmage, Jesus the Christ, 155.

[36] Contrast this with the story in Acts 21, wherein the people react violently to Paul’s alleged gentile companionship and the Roman centurions storm into the Court of the Gentiles to evacuatePaul from the mob of people.

[37] Klyne R. Snodgrass, “The Temple Incident,” Key Events in the Life of the Historical Jesus, eds. Darrell L. Bock and Robert L. Webb, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2010), 462. Emphasis in original.

[38] Victor Eppstein, “The Historicity of the Gospel Account of the Cleansing of the Temple,” Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft 55, no. 1 (1964): 42–58.

[39] Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler, The Jewish Annotated New Testament: New Revised Standard Version Bible Translation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 141.

[40] James E. Faust, “Search Me, O God, and Know My Heart,” Ensign, May 1998, www.churchofjesuschrist.org.

[41] I chose to quote Matthew’s version because of its emphasis on the leaders “shutting up the kingdom.” Mark is actually the specific author that places this teaching within the temple on the day following the cleansing.

[42] This teaching has been reiterated by President Russell M. Nelson: “One of the easiest ways to identify a true follower of Jesus Christ is how compassionately that person treats other people.”

Russell M. Nelson, “Peacemakers Needed” (general conference talk, May 2023), www.churchofjesuschrist.org; emphasis in original.

[43] Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 20.9.2–4.

[44] Evans, Jesus and His Contemporaries, 355; Chilton, Temple of Jesus, 107–11.

[45] Some argue that Ananias’s refusal to pay tithes while using the tithes of others for himself is what prompted Jesus to give the parable of the wicked tenants (Matthew 21:33–43). For more information, see Randall Buth and Brian Kvasnica, “Temple Authorities and Tithe Evasion: The Linguistic Background and Impact of the Parable of the Vineyard, the Tenants and the Son,” in Jesus’ Last Week: Jerusalem Studies in the Synoptic Gospels, vol. 1, ed. R. Steven Notley, Marc Turnage, and Brain Becker (Leiden: Brill, 1994).

[46] Joseph Benson, Complete Bible Commentary, John 2:14, https://

It is worth noting Snodgrass’s hesitancy to exclusively tie the cleansing to corruption in the temple practice: “Apart from the Testament of Moses, not much of the evidence is an explicit condemnation of the temple in Jesus’ day, but virtually every period for which we do have evidence points to corruption. It would be naïve to argue corruption was not a factor. However, this does not prove that corruption was the motivating factor for Jesus. The same can be said for the offensive coins of the money changers.” Snodgrass, “Temple Incident,” 462; emphasis in original.

[47] For more information on the economic gouging by temple personnel, see Evans, Jesus and His Contemporaries, 319–44; and Snodgrass, “Temple Incident,” 455–62.

[48] Benson, Complete Bible Commentary, John 2:14; Leen Ritmeyer “The Temple Mount and the Money Changers,” Bible Odyssey, https://

[49] Mishnah Kerithoth 1.7. The account relates that Rabban Shimon ben Gamaliel, upon discovering the absurd price increase, personally crusaded to lower prices back down to the regular one-quarter of a silver dinar within a day. This happened sometime between 40 and 70 CE, reflecting that it might have been common practice to adjust prices according to demands during Jesus’s time.

[50] A notable example of this is when Joseph and Mary, in their state of poverty, offered turtledoves after Christ’s birth (Luke 2:22–24).

[51] One scholar argued that Christ’s challenging of the temple’s banking system was a direct claim for kingship.

Neill Q. Hamilton, “Temple Cleansing and Temple Bank,” Journal of Biblical Literature 83, no. 4 (December 1964): 365–72.

[52] “The Syriac and Ethiopic versions read, ‘they brought unto him the blind and the lame’. The blind could not come to him unless they were led, nor the lame, unless they were carried: the sense therefore is, they came, being brought to him.” John Gill, Gill’s Exposition of the Entire Bible, Matthew 21:14, https://

[53] Elias J. Bickerman, “The Warning Inscriptions of Herod’s Temple,” Jewish Quarterly Review 37, no. 4 (April 1947): 387–405.

[54] Josephus, Jewish War 5.194.

[55] “Within the boundaries of the sanctuary, what was known to be pure was offered by personnel chosen for the purpose, in the presence of God and of God himself. Nothing foreign, no one with a serious defect or impurity, nothing unclean was permitted. . . . The practice of the Temple and its sacrificial worship was centered upon the demarcation and the consumption of purity in its place, with the result that god’s holiness could be safely enjoyed, within his four walls, and the walls of male and female Israel.” Chilton, Temple of Jesus, 106; Josephus, Jewish War 4.9.3.

[56] Davidson Razafiarivony, “Exclusion of the Blind and Lame from the Temple and the Indignation of the Religious Leaders in Matt 21:12–15,” American Journal of Biblical Theology 19, no. 34 (2018): 7–8.

[57] For example, one scholar offers this alternative view: “More likely though, disabled people seemed to have played a more active role in the Jebusite cult center prior to the capture by David, but are considered impure by Israelite standards. For this reason, they are subsequently excluded from the temple once it was built shortly after David’s reign.” Thomas Hentrich, “The ‘Lame’ in Lev 21, 17–23 and 2 Sam 5, 6–8,” Annual of the Japanese Biblical Institute 29 (2003): 19.

[58] Charles John Ellicott argued that the Septuagint Bible, which contains the specific wording “The blind and the lame shall not come into the house of the Lord,” is interpreted incorrectly because “it would seem as if this were a departure from the usual regulations of the Temple; but the words in italics are not in the Hebrew. Most commentators give an entirely different meaning to the proverb, and there is no evidence from Jewish writers that the blind and the lame were ever, as a matter of fact, excluded from the Temple.” Ellicott’s Commentary for English Readers, https://

[59] Hentrich, “The ‘Lame’ in Lev 21, 17–23 and 2 Sam 5, 6–8,” 19. Another possible explanation stems from the account of Jesus healing a blind man in John 9. Upon finding the blind man, the disciples asked, “Master, who did sin, this man, or his parents, that he was born blind?” (v. 2). The question stems from a belief that physical maladies were a result of sin rather than life in a fallen world. Jesus corrected this line of thought by teaching that “neither hath this man sinned, nor his parents: but that the works of God should be made manifest in him” (v. 3). The disciples were not alone in their mistaken belief, though, as the local Pharisees cried, “Thou wast altogether born in sins, and dost thou teach us?” as they cast out the now-healed man from the synagogue (v. 34). It is clear from the reaction from both the disciples and Pharisees that it was a common societal expectation that spiritual impurity manifested itself in physical maladies.

[60] Justin Taylor asserted that that the Beautiful gate was an entrance into the inner sanctuary: “Although other biblical legislation excludes descendants of Aaron who are lame or otherwise disabled from exercising their priestly function (Lev 21:17–21), there is none that excludes the disabled from the body of worshippers. Nor is there any reference in Josephus or the Mishnah to the exclusion of the lame as such from the Temple. In any case, there is no reason why they could not have entered areas permitted to Gentiles. But could they go further? The position is far from clear. In any case, a gate leading from the outer court into that reserved for Jews would be a suitable place in which to beg from worshippers. Our other arguments would identify this as the gate on the eastern side leading directly in the women’s section, namely the ‘Corinthian’ or ‘Nicanor’ gate” (561). Justin Taylor, “The Gate of the Temple Called ‘The Beautiful’ (Acts 3:2, 10),” Revue Biblique 106, no. 4 (October 1999): 549–62.

[61] There is an argument that the healed man actually entered onto the Temple Mount with Peter and John, not into the inner sanctuary. Verse 8 clearly states that he “entered with them into the temple,” and then we find that they are gathered at Solomon’s Porch in verse 11. One view argues that some texts indicate that the three men left the inner sanctuary before going to Solomon’s Porch: “A quite different impression is given by the text of v. 11 according to Codex Bezae (D) and, in part, the Latin Fleury palimpsest (h) and the Coptic of Middle Egypt (mae). The Western text, as we shall call it, translated literally is: ‘Now, as Peter was coming out and John, he [the cured man] came out with (them) holding on to them; but those who were awestricken stood in the portico Solomon.’ The sentence is awkwardly constructed, but it clearly implies that the portico of Solomon is outside the Temple (tò iepóv) into which the three have gone in v. 8 and from which they now “come out.” Unless we are to suppose that the writer thinks of the portico of Solomon as altogether outside the Temple area—which seems unlikely—we must infer that for this writer (tò iepóv) of v. 8 refers, not to the whole Temple Mount, but to some part within it; not, of course, to the Sanctuary itself, but to one of the restricted areas.” Taylor, “Gate of the Temple Called ‘The Beautiful,’” 552–53.

[62] Razafiarivony, “Exclusion of the Blind and Lame from the Temple,” 16.

[63] Michael J. Wilkins, Matthew, NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004), 692.

[64] Snodgrass, “Temple Incident,” 474; emphasis in original.

[65] Trent C. Butler, “Lame, Lameness,” in Holman Bible Dictionary (Nashville: Broadman and Holman, 1991).

[66] Razafiarivony, “Exclusion of the Blind and Lame from the Temple,” 21.

[67] “For the zeal of thine house hath eaten me up; and the reproaches of them that reproached thee are fallen upon me” (Psalm 69:9)

[68] There are many other references that demonstrate Christ’s devotion to his Father. Only a handful of references have been selected here to demonstrate this repeated theme in John’s Gospel.

[69] Russell M. Nelson, “Rejoice in the Gift of Priesthood Keys” (general conference talk, April 2024), www.churchofjesuschrist.org.

[70] It is important to note that though Jesus removed the manmade and corrupt barriers within the temple, he did not come to destroy the law but to fulfill it (Matthew 5:17). Celestial law still demanded that nothing unclean be received into the presence of God (Alma 7:21). Yet through the mercy, merits, and grace of the Holy Messiah (2 Nephi 2:8), all could be purified through sacrifice and repentance, thus allowing them to ascend to the house of the Lord with clean hands and a pure heart (Psalm 24:3–4).