Helping Young Adults Work through Complex Issues of Faith

Daniel R. Winder

Daniel R. Winder, "Helping Young Adults Work through Complex Issues of Faith," Religious Educator 24, no. 3 (2023): 121–47.

Daniel R. Winder (daniel.winder@ChurchofJesusChrist.org) teaches at the Utah Valley Institute of Religion and has researched, coordinated, and taught in Seminaries and Institutes for twenty-five years.

Inquiring young adults often see themselves as a social-change advocates and compassionate sympathizers but outsiders to mainstream Church membership. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Inquiring young adults often see themselves as a social-change advocates and compassionate sympathizers but outsiders to mainstream Church membership. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Keywords: faith, intellect, wisdom

A few years ago, Chad Webb shared a story in which a medical examiner was able to determine that an unidentified person had lived their entire life in Los Angeles by examining the pollution found in his lungs. Webb said, “It has made me wonder if it were possible to do a spiritual autopsy, if someone could say, ‘I can tell from your attitudes about certain ideas and issues, that you must have lived on earth in 2019.’”[1] The spiritual “air quality,” so to speak, has changed over time, and as a result, so have the attitudes, beliefs, and moral compasses of young adults (YAs).

Many of the YAs’ worldviews that form the foundation of their morality are not fully understood and are dismissed by some parents, teachers, or leaders (PTLs) as evidence of a rebellious or a deceived young mind. The result of a PTL’s misinterpretation of their moral values is that many YAs feel marginalized by the previous generation for simply not thinking and doing things the same way. As a result, the inquiring YA with complex issues of faith often sees him or herself as a social-change advocate and a compassionate sympathizer, but an outsider to mainstream Church membership.

To dispel this misunderstanding and dismissiveness, many PTLs are making wonderful efforts to help YAs deepen their conversion and feel that they belong.[2] PTLs are seeking to help YAs feel that the Church is on their side as they seek fulfillment, explore, wander, and “do different” than the previous generations—that Christianity is not solely about rules and boundaries.[3] PTLs need to better help YAs see their religion as an avenue for the moral principles they are adopting and see the kingdom of God as the ultimate just society, rather than feeling that their moral code conflicts with their organized religion.

This paper will provide PTLs with understanding, frameworks, methods, and strategies to help YAs navigate through the unique moral and social challenges of the day with their faith intact and help PTLs equip YAs with the skills they need to see through subtle sophistry and find peace in the gospel of Jesus Christ. The pedagogy will be broken up into two main areas—disentangling and analyzing. In each area, methods and principles will be discussed that can help give PTLs specific strategies when working with YAs. Many of these methods are guided metacognitive learning strategies that involve planning, monitoring, evaluating, and adapting one’s thinking. This self-awareness will teach YAs to think deeply by analyzing the assumptions behind their statements or questions and using logic and principles of conversion to disentangle faith issues from nonfaith issues.

Method 1: Disentangling

Inquiring YAs that are willing to engage in a spiritual wrestle[4] will find that many complex issues of faith are entangled with their worldview, moral reasoning preferences, views on religious orthodoxy, and behaviors. Disentangling a spiritual or moral issue to understand where it resides (that is, what we are really dealing with) is critical in knowing what intervention will be most helpful for the YA. Therefore, this section presents a foundational understanding of moral reasoning principles and a classification framework for identifying where a complex issue resides, what is influencing it, and what is needed for its resolution.

First, understand YAs’ principle-based moral reasoning

YAs morally reason differently than the majority of PTLs. Unless this reality is recognized, the process of helping a YA navigate a complex issue of faith may be frustrating and unproductive. To illustrate such frustration, suppose a YA brings up a complex issue in a religious class. The PTL gives a response that helped them attain resolution of the issue thirty years ago. The student leaves class, posts on their social media that the Church is offensively outdated, and never returns. Their post gains likes and promotional assistance from like-minded persons, and their personal issue becomes a proxy issue for other young adults who leave the Church. The bewildered PTL’s intentions were not bad, and their anachronistic answers were not false, but their methods for navigating a moral issue were unintentionally dismissive because they lacked a foundational understanding of the YA’s current moral reasoning principles.

To give more concrete evidence of changing moral reasoning schemas among YAs, one only needs to compare moral reasoning differences between BYU religion students in the 1980s and BYU students in the 2000s.[5] In only one generation, BYU religion students became significantly less likely to refer to rules, laws, commandments, authorities, and formal structures of society to determine what is right in a just society. Conversely, the students from the newer generation were more likely to refer to principle-based moral reasoning in defining a just society.[6]

What this means for PTLs is that when it comes to determining what makes for a moral society, an appeal to authority (such as the words of a prophet), historical precedence (such as evidence from the Bible of God withholding priesthood privileges to certain groups), or canonized scripture (both modern and ancient) just doesn’t carry the same weight for today’s YAs as it used to. But many PTLs continue to employ these methods of reconciliation to YAs who resist or, in some instances, reject those very standards. As one YA recently said, “I just can’t understand for the life of me how someone can do something just because the prophet said so.” So what do YAs use to determine what is right? They use moral principles.

Principles are truths that can be applied in multiple ways to various circumstances.[7] Here are some of today’s popular moral principles that form YAs’ “just society”:

- Beneficence (the quality of doing good)

- Nonmaleficence (not causing harm or destruction to another person or group)

- Respect for autonomy (the right of individualism and self-government)

- Reciprocity in a just society (a mutual exchange of privileges)

- Nonjudgmental inclusion (note that the opposite of this principle, exclusion, is abhorred)

- Moral diversity (being free to choose multiple paths to goodness, meaning, and fulfillment)

- Consensus (moral code of a culture that comes from open communication and consensus)

- Macromorality in general (the rules and rights of a just society)

Recognizing the above principles, understanding them, and discussing them with YAs will lead to greater openness and foster a discussion of how to apply these true principles with tempering eternal truths and principles. In addition, it is useful to help YAs see hyperbole—that an unchecked virtue taken to an extreme becomes an unstable virtue.[8] But that doesn’t mean the initial virtue is not good, nor that the person seeking to apply such a virtue is rebellious; inexperience, not malintent, is often to blame for misapplication of a virtue. And there are many good virtues in the moral principles that YAs adhere to, principles that will lead to a Zion people.

The challenge for many PTLs is a need to carefully communicate understanding of and sympathy for complex moral issues while still holding onto the concept that sin is still sin and righteousness still righteousness, because “ultimately, a society without a belief in sin has no need of a saviour” (see 2 Nephi 2:13).[9] For example, a YA may be basing their moral reasoning on a true principle but may be misapplying a principle or applying it in isolation or with inconsistent logic. When a PTL sees the flawed logic, the tendency is to immediately point it out rather than help the YA discover it for themselves. Guided discovery is crucial in moral reasoning because “the most important learnings of life are caught—not taught.”[10] Thus the “Goldilocks” balancing act of understanding and appreciating a well-intentioned (yet flawed) YA worldview and mentoring a YA as they navigate complexity is threefold:

- Reassure a YA of a respect for their autonomy and a realization that there are many principles that lead to temporal happiness, fulfillment, moral goodness, and success in life; the Church has no monopoly there. Applying goodness is in all people’s purview.

- Communicate that faith, repentance, obedience, sacrifice, chastity, and consecration are divine principles and laws to be lived in concert with the quest for temporal and eternal fulfillment.

- Accept and genuinely communicate that how YAs apply all those principles and laws may look a little different from the previous generation—and that’s OK. Learning to apply metacognitive moral reasoning to check the appropriateness of their application of true principles and laws can be facilitated by identifying assumptions and logical conclusions.

The PTL is to be a patient moral mentor in this process and employ the right amount of charity and clarity on an issue at just the right time. Showing Christlike understanding, acknowledgement of goodness, and respect of YAs’ moral principles will foster the desired openness. Further, a PTL should humbly recognize that they have much to learn from hearing how YAs apply truth, and thus both can “understand one another” and be “edified and rejoice together” (Doctrine and Covenants 50:22).

Disentangle what is needed for resolution by classifying the domain where the issue resides

The root of most issues grows out of one or more of four domains: The mind (cognitive), the heart (affective), actions (behavior), and the soul (revelation). Many complex issues overlap (thus the Venn diagram rather than a quadrant; see fig. 1)—a cognitive issue may create an affective issue or vice versa (that is, doctrinal drifts often create attitudinal drifts). However, what is needed for resolution often resides in one main domain.

Figure 1. A framework for classifying complex issues.

Figure 1. A framework for classifying complex issues.

A good example of why using this framework to disentangle a complex issue is so crucial to resolution for YAs, can be summarized by an experience Jared Halverson had with a student years ago. The student came into his office wanting to talk about concerns over polygamy. She had a list of questions and for about two hours he did his best to answer them, giving her greater historical context and expanded doctrinal clarification, but after all the questions were exhausted, he could tell she was still unsettled. Finally, he asked something like, “Tell me why polygamy is upsetting to you personally.” She then said that as an older, unmarried sister, it was highly probable that if she ever did marry, she would likely be a “second wife” and she didn’t want to be “second.” Now he knew her real issue. All of his reliable sources and historical context didn’t help because ultimately her issue was one of the heart, not the mind. Once he had learned the real issue, he could offer empathy and go in the right direction, but he couldn’t do so until he understood what the issue was really about.[11] Thus disentangling is a process of helping PTLs and YAs recognize where the real issue resides.

Some issues are not necessarily about the reliability of the source or the eternal perspective—the conflict is about the feelings, motives, desires, actions, spiritual witnesses, and values that the YA has regarding the issue (“I understand the doctrine, but it just doesn’t feel right to me”). And YAs wonder how to act in faith when their conscience tells them otherwise. Instead of coming to a halt when their moral code directly contradicts their religious tenants, a YA can be helped by a PTL who provides a guided disentangling of the four areas to help the YA move towards reconciliation and continued activity in the Church. The overarching question that may best facilitate disentanglement of these four areas, and is best to ask early in the disentangling process, is this: What do you need in order to have reconciliation with your faith?

The mind (cognition). Complex issues of understanding are the easiest to identify to a knowledgeable person. Because the current pedagogy is very effective for resolving these issues, I will not spend much time on this area. These issues often come from a misunderstanding or misconception, distorted or decontextualized or incomplete information, shallow learning, fallacious logic, flat-out deception, or popular soundbite rather than thoughtful scrutiny. In short, a student may be wrestling with misinformation, misconception, blindness from sophistry, or a simple lack of knowledge. And like Alma the Younger, sometimes it takes a moment of great intellectual humility[12] to reconsider a claim or position when additional light and truth is given.

Some common examples of complex issues of cognition follow:

- “Joseph Smith married teenage brides. That seems off.” (Issue: presentism and context; views on appropriate age of marriage and sealing were somewhat different back then).

- “Why is your Church homophobic?” (Issue: misunderstanding; we support traditional marriage and love our LGBTQ+ brothers and sisters).

- “Why can’t I be a female minister like in other religions?” (Issue: misconception; LDS women do what most female ministers do in other religions—preach sermons, do home visits, run meetings and budgets, administer saving ordinances, lead, etc. However, the Lord has made some callings gender-specific, with no explanation why).

The heart (affective). Complex issues of the heart can be in multiple layers: feelings/

Some common examples of issues of the heart:

- “As a divorced older woman, I don’t feel I belong in such a family-oriented church.”

- “Some past practices in the Church were racist by today’s standards. It’s very hurtful.”

- “The Church didn’t tell the full history. People who did got chastised. I can’t trust them.”

- “I get the doctrine of the eternal family, but it makes heaven feel too exclusive to me.”

Because feelings can be deep and sometimes subconscious, these types of concerns can be difficult to pin down. After expressing genuine empathy, helping a student analyze why they feel a certain way is an important precursor to analyzing their assumptions. Disentangling the issue from their feelings can be facilitated by asking layers of intentional questions. Some questions seek clarification, while others grapple with the assumptions or aid in paradigm shifts (see Table 1).

Table 1. Intentional question types and examples.

| Question type | Examples |

| Clarification | What do you mean when you say X? Could you explain that point further? Can you provide an example? How do you reconcile other things that are painful in your life? |

| Values | What values are misaligning or competing here? Are you consistently applying your values to individuals (or institutions)? As we peel back the catchy slogan, does the point truly align with your values? Could there be other values or desires at play here? How has the Savior said he feels about . . . ? What do you know about God’s values that can help you with . . . ? |

| Challenging assumptions | Is there a different point of view? What assumptions are we making here? Are you saying that . . . ? Is every part of your argument true? Are there complementary truths or conditions that could make the assumption more fully true? |

| Evidence and reasoning | Can you provide an example that supports what you are saying? Can we validate that evidence? Do we have all the information we need? |

| Alternative viewpoints | Are there alternative viewpoints? How could someone else respond, and why? Is that the only motive? Is that the only way of looking at the issue? |

| Implications & consequences | How would this affect someone? What are the long-term implications of this? Where will it lead? |

| Challenging the question | What do you think was important about that question? What would have been a better question to ask? |

Adapted from Jeremy Sutton, “Socratic Questioning in Psychology: Examples and Techniques,” Positive Psychology (blog), June 19, 2020. These questions help disentangle all domains, not just affective.

Reconciliation for many affective issues requires a different approach than reconciliation for cognitive issues. For example, a PTL may find that, like the tears of the legendary phoenix, genuine tears of empathy often heal more than words or logic when a student is hurting over a policy or doctrine. Sincere mourning with and comforting of those in need may be the only appropriate consolation for some affective issues. Thus showing charity and turning a person to Jesus Christ is the best approach for issues of the affective domain.

A final aspect of the affective domain that is critical to understand is how a person feels about their religion. Religious orthodoxy refers to how well a person accepts and adheres to their religious creeds.[14] A conventional view on religious orthodoxy would be one that adheres to and believes in widely accepted authoritative interpretations, sometimes viewed as conformist and sometimes as deferring to rules. A nonconventional view would be one that does not view tradition, accepted dogma, or an appeal to authority as sufficient for policies or practices, sometimes viewed as nonconformist or acceptable disorder—that is, if one is doing something acceptable to God and fellow man, one is good. In the middle of these two differing views is the idea of adaptable principles—that religion should “teach [people] correct principles and let them govern themselves.”[15]

Table 2. Religious orthodoxy

| Topics | Conventional views on religious orthodoxy | Nonconventional views on religious orthodoxy |

| Interpretation and application of truth | Authoritative interpretation: laws, rules, norms, order, tradition, commandments define appropriate application. Principles may guide application if they don’t lead to chaos/ | All interpretations are valid if based on true principles/ |

| Faith Practice | Sunday stalwarts, very involved in faith practices; nonparticipants are wayward. Ritual/ | Spiritual but not religious. Ordinances and buildings are not what faith is about; one’s heart and goodness are enough. |

| Meaningfulness | Faith is the single most important source for meaning in life. All meaningful elements of life are connected to faith. Pursuits should not invade on faith practices. | Families, friends, careers, outdoors, pets, listening to music, reading, and faith all have equal meaning in life. Many paths to fulfillment and meaning. |

| Social issues or causes for advocacy | Partnerships for good causes; individual service over social advocacy. Means and ends of social advocacy matter. Jesus will fix all social issues when he comes again. Marginalized need love/ | Social advocacy is what Jesus was all about. Those who do not join in social advocacy are either uninformed, unenlightened, or immoral. The marginalized need a hero. |

Some concepts in this table are from the Pew Research Center’s 2018 report on religion.[16]

Adaptable principles acknowledge that the truth or application of a moral law is often in the middle of the spectrum. The moral law is not rigid conventionality nor dismissive relativism. For example, Emma Hale believed the law to “honor thy father and mother.” Joseph Smith followed social etiquette of the day and asked Emma’s father for permission to marry her. When that was denied due to biased views of Joseph Smith, Emma determined that the moral thing to do was not to strictly adhere to her parents’ commands. Emma and Joseph eloped and later made peace with her parents.

While the majority of current PTLs in the Church, as well as many YAs, lean to conventional religious orthodoxy, there is a growing number of today’s YAs, especially those who see themselves as inquirers, who adhere to more unconventional orthodoxy. To help minimize the possible conflict between conventional PTLs and nonconventional YAs in approaching complex issues, a preemptive agreement that both may fall in a different spot on a religious orthodoxy spectrum is helpful. Also, mature statements such as “we don’t have to agree or see all things the same way to be friends, have a cordial discussion, or to be faithful” are helpful scripts to keep a healthy relationship and safe space to discuss questions.

Once YAs determine where they fall on the spectrum of religious orthodoxy (and their position is likely to shift along the spectrum depending on the issue), it is helpful to explore the relative strengths and weaknesses of conventional and nonconventional orthodoxy. For instance, individuals following conventional orthodoxy adhere to prophets and scripture because they view these as being directly tied to God, creating a solid foundation on which to build. The weakness of conventional orthodoxy here is dogmatic absolutism (a black and white reality between right and wrong which excludes those who question conventionality). This weakness is what the nonconventional resist; they embrace, instead, a more nonconventional orthodoxy for its tendency towards inclusivity and individualism, which has many positive, Christlike virtues. The weakness in nonconventionality is that due to the lack of authoritative views, each may become a law unto themselves rather than a law of God (see Doctrine and Covenants 88:35). And principles devoid of divine authority must be open to additional scrutiny to enable the YA to seek understanding and appropriate application of true moral principles. Helping a student be aware of such strengths and weaknesses will help them be aware of themselves, thus disentangling how religious orthodoxy influences their complex issue of faith and help them better navigate complex issues.

Actions (behavioral). To illustrate the importance of analyzing one’s actions, I share a relevant conversation with an agnostic friend in which he concluded that if the Book of Mormon were true, then God was real, and Joseph Smith was a true prophet. Then he abruptly said, “but I would never join your church even if I knew that book was true. It’s too strict.” Clearly, his real issue was living the truth, not the discovery of the truth. And since he didn’t want to confront the real issue of “I don’t want to deny myself of some things,” few religions could ever make any progress with him—agnosticism was a moral convenience.

This story also illustrates the concept of dissonance. Dissonance occurs when one’s beliefs (or values, attitudes, desires, motives) and behaviors do not align. And sometimes it seems easier to change one’s beliefs rather than one’s behaviors. Thus while contemplating the demanding sacrifices of discipleship, many would-be-disciples often consider, then adopt, philosophies of the world for a respite to their otherwise “rebellious” religious actions. Being aware of the concept of dissonance is an appropriate method in disentangling elements of behavior.

A student may manifest a complex behavioral issue by showing an unwillingness to commit (“I don’t want to be that good”), misapplying truth (“what about agency?”), performing invalid actions or inaction (doing the right things for the wrong reasons), setting unreachable or misaligned goals (being over/

In many cases, the YA will say “my religion says I should do this” rather than “I know I should do this,” essentially making their faith a third-party sheriff. When a YA makes “my religion” a third-party sheriff, it’s much easier to claim that religion is about an ideal world of what we should do. In this case, helping a YA act in faith by taking ownership of what they believe and helping them plan an appropriate next step is key. Caution the YA not to misplace guilt and shame for not belonging with those whom they perceive as having constant joy. Teach that their divine identity and their worth is infinite to their heavenly parents independent of their behavior—that “worthiness is not flawlessness.”[17] Also, help them see they are living more commandments than they are breaking. Understanding the true definitions of sin and repentance are also helpful. In Hebrew, the word sin “comes from the archery term for when an archer missed the mark.”[18] Conversely, repentance in Hebrew means “to turn,” meaning to turn back to God.[19] Understanding these terms takes much condemnation and shaming out of the two concepts.

Finally, PTLs must not underestimate the difficulty to change when an addiction or mental illness[20] is present in some behavioral complexities. Many of the complex issues in the behavioral realm are best handled by local leaders of the Church and trained professionals.

The soul (revelation). Complex issues in the spiritual realm occur when one lacks a witness from a divine source. These issues of the soul differ from the behavioral realm because the issue resides in the YA’s soul, not his or her actions. It is different from the knowledge realm because it has less to do with cognitive understanding and more to do with a spiritual witness from the Holy Spirit: knowing from heaven, not mortal man, that something is true or moral. The spiritual realm is also different from a complex issue of the heart in that it is not about an internally controlled attitude, desire, or motive, but about obtaining an external divine manifestation from heaven, on heaven’s timetable and according to heaven’s laws.

The most difficult aspect of this element is that the YA is not fully in the driver’s seat. They can comply with law, apply principles, and seek confirmations, but they cannot force divine answers. C. S. Lewis’s comment that Aslan (Christ) is “not a tame lion” seems appropriate here in that one cannot give mortal ultimatums when seeking answers from divinity.[21] And we don’t always know why it sometimes takes longer to get a spiritual witness and why some have greater witnesses than others for seemingly lesser efforts. I simply conclude that all things are “done in the wisdom of him who knoweth all things” (2 Nephi 2:24).

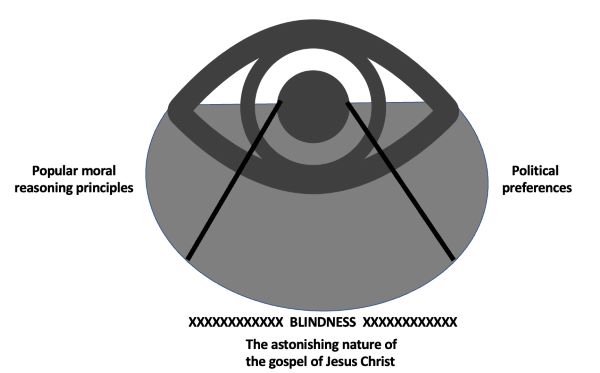

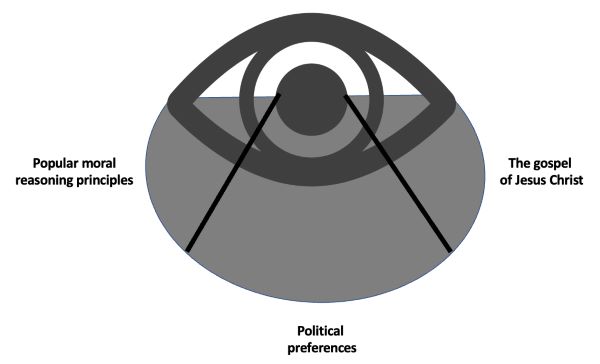

Figure 2a. Spiritual blindness can block one from seeing the astonishing nature of the gospel.

Figure 2a. Spiritual blindness can block one from seeing the astonishing nature of the gospel.

Figure 2b.A hyper-focus on temporal issues can push the gospel to the peripheral of one’s life.

Figure 2b.A hyper-focus on temporal issues can push the gospel to the peripheral of one’s life.

Remember, the whole point of disentangling is to separate one’s issue of faith from one’s worldview. Therefore, disentangling must include an honest assessment of what takes center stage in one’s mind and heart. William James, a great writer of religious philosophy, speaks of conversion as “the hot place in a man’s consciousness, the group of ideas to which he devotes himself, and from which he works.” He adds a layer to our idea of conversion by framing it in terms of the “centre of [one’s] personal energy.” He states, “It makes a great difference to a man whether one set of his ideas, or another, be the center of his energy,” and which ideas remain peripheral. “To say that a man is ‘converted’ means, in these terms, that religious ideas, previously peripheral in his consciousness, now take a central place, and that religious aims form the habitual centre of his energy.”[22] Elder Gilbert also taught a similar concept of peripheral and secondary issues in a recent broadcast as he spoke of YAs who, becoming blinded to the astonishing nature of the gospel, end up “‘filling in’ what they can’t see right in front of them with interpretations of what they see in their periphery.”[23]

To illustrate a similar concept, some in the Church often become so passionate or entrenched in social justice causes, opinions, moral reasoning principles, or politics that should be peripheral to their conversion to Jesus Christ and his gospel, that the peripheral can become the center and what was once the center gets relegated to the peripheral. Thus out of balance, and often unawares, they (by James’s definition) become “converted” to a peripheral cause or practice rather than to the Savior. For example, sometimes defining Christ in terms of political or social movements gets in the way of accepting the true Messiah (#notMYmessiah; see John 6). A little humility can help one to realize that Jesus may not be in our preferred political party—he already has his own kingdom.

A PTL may help a YA disentangle what viewpoints or dissonance might be swaying an issue by

- Helping them change what is taking central stage in their conversion (that is, initiating a paradigm shift),

- Compartmentalizing a tangential issue (so it doesn’t take center stage), and

- Helping them simultaneously hold on to two conflicting stances.

Ask clarifying questions such as: are politics, desires, behaviors, social trends, moral values, other preferences, etc. eclipsing elements of conversion, like the Spirit, meaningful prayer, sincere and consistent scripture study, and deep doctrinal understandings? Can you change, compartmentalize, or hold onto two conflicting stances on this issue? For example, I can know that Brigham Young was an inspired prophet whose teachings fill me with faith, and I can know that he implemented policies I don’t agree with. To stay active in the Church, many inquiring YAs simultaneously hold onto two conflicting stances—and that nonconventional view is better than leaving. Further, some PTLs may also need to embrace a level of complexity in thought, different from their own black-and-white views, to fully accept YA inquirers who hold conflicting stances.

Disentangle personal or proxy issues

A final aspect of disentangling is learning to separate personal issues from proxy issues. When Jesus was accused of sedition and treason, he was brought before Pilate and asked whether he considered himself the king of the Jews. Jesus wisely answered with an introspective question: “Sayest thou this thing of thyself, or did others tell it thee of me?” (John 18:34; emphasis added). Jesus invited his learners to examine whether their premises were their own (personal) or someone else’s (proxy) before asserting them or acting on them. Thus, classifying whether a student is struggling with a personal issue or a proxy issue of faith is a key component in determining differing strategies for navigating the complex issue.

If it is a YA’s personal issue and he or she is willing to confront, wrestle, and own the assumptions of the issue, then analyzing the origin of the complex issue may be the next step. However, often we have incomplete knowledge on many of these complex personal issues, hence the need for patience and faith (Doctrine and Covenants 21:5). For PTLs helping YAs navigate a personal or proxy issue, I would recommend you keep in mind the idea of putting together a puzzle. When doing a puzzle, there are many times a puzzle piece doesn’t seem to fit anywhere. When this happens, you put the piece aside and continue moving forward, putting other pieces into place until you find where all the pieces fit. Imagine if you were doing a puzzle and every time you had a puzzle piece that didn’t seem to fit, you simply threw it away in frustration. Similarly, with some faith issues, especially those that don’t seem to “fit” in our current gospel picture, YAs may be tempted to throw out that particular issue altogether or determine that if it doesn’t have a place now, it never will. PTLs can instead help a YA put that piece of the puzzle aside—not entirely abandoning it or throwing it away, but continuing, waiting for further light and knowledge to come until he or she can see how it all fits together. Developing habits of spiritual endurance and seeking divine grace during what will likely be a long journey is often what is most needed to navigate personal issues.

Because they value inclusion and nonmaleficence (not causing harm or destruction to another person or group), it is very common for YAs today to sit in our classes or meetings with their nonconventional friend or family member figuratively sitting on their shoulder. The words or topics being discussed may not be personally hurtful to themselves, but they would be to their friend were they in the room, and if it would offend their friend, it offends them. These are proxy issues. Proxy issues can be close to the person (for example, “my brother is attracted to the same gender”) or it can be more distant (for example, “I read about someone on social media that . . .”). An initial method to approach a proxy issue is to consider the source and reliability of one’s knowledge.[24] Proxy issues are complicated, convoluted, and often darkly manipulated by false prophets who use their “word only” (Alma 30:40). Thus, the need is not only to disentangle but also to help a student analyze the validity of the source and of the issue.

Method 2: Analyze to Discern Truth

PTLs have a great responsibility to help the young people of the Church “think clearly about the application of eternal gospel truths and teachings to the various circumstances we face in mortality.”[25] But when a YA chooses to use moral principles rather than authoritative interpretations to define truth, they cannot always “be sure that [their] conclusions are true.”[26] Thus a healthy amount of scrutiny should be welcomed and applied. However, a major stumbling block for many YAs is the inability to logically scrutinize the arguments or sophistry presented to them in social forums or interactions. Therefore, these methods will enable YAs to analyze the assumptions, either implied or explicit, in their moral and social questions or conclusions, helping them learn to state logic and, most importantly, how to scrutinize logic–whether it be their own or that of the world around them.

It’s OK to ask questions and reason with the Lord

The Lord loves and invites a logical discussion of any honest faith issue. Consider the following quotes: “Come now, and let us reason together” (Isaiah 1:18). “Produce your cause, saith the Lord; bring forth your strong reasons” (Isaiah 41:21). And “questions are good.”[27]

Socratic questioning method

Socratic questioning “is widely used in teaching and counseling to expose and unravel deeply held values and beliefs that frame and support what we think and say.”[28] All the methods in this paper have an element of Socratic questioning. Sutton gives five steps to employ Socratic questioning:

- Understand the belief. Ask the person to clearly state their belief/

argument. - Sum up the person’s argument. Repeat back what they said to clarify your understanding of their position.

- Ask for evidence. Ask open questions to elicit further knowledge and uncover assumptions, misconceptions, inconsistencies, and contradictions.

- Upon what assumption is this belief based? (What does this question assume?)

- What evidence is there to support this argument? (What makes you think this is true? have you seen this or have evidence of it?)

- Challenge their assumptions. If contradictions, inconsistencies, exceptions, or counterexamples are identified, then ask the person to either disregard the belief or restate it more precisely.

- Repeat the process again, if required. Until both parties accept the restated belief, the process is repeated.[29]

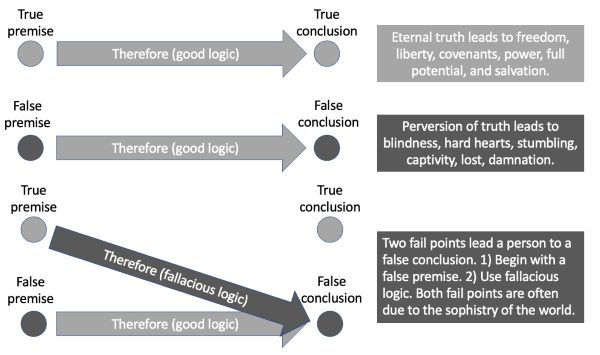

To employ Socratic questioning methods, a teacher must be able to identify a premise, logic, or conclusion and discuss it in the form of a question. Therefore, once a student’s logic is understood, it is important for a teacher to have a rudimentary understanding of common fail points in logic. There are two main points where logic usually fails. The premise is false (the starting point is false) or fallacious logic (the “therefores” are not logical—see fig. 3).

Figure 3. Identifying good logic versus fallacious logic.

Figure 3. Identifying good logic versus fallacious logic.

If a premise is false, the conclusion may be logical but also equally false. For example, consider the following premise: Prophets must be perfect (false), and Joseph Smith was not perfect (true). Therefore, he was not a true prophet (false). The logic is there, but the starting point of this reasoning is where the falsehood crept in. Prophets most often attack the premise of an argument rather than the conclusion (see, for example, 2 Nephi 29; Jasher 11:40–43). Therefore, to help a YA reason through an issue, PTLs must help identify the assumption behind a claim or question and check to see if the premise is true, logical, and aligns with their thinking and values. To learn more methods and see further examples of analyzing logic, see footnote.[30]

See through the sophistry

Henry Ford said, “Thinking is the hardest work any one can do—which is probably the reason why we have so few thinkers.”[31] And proxy issues are often not given the same level of critical thinking and scrutiny as personal issues. Most often, a proxy issue surfaces in a student who is seeking to confront evil through fairness or justice or truth (the concept of a “social justice warrior”). The issues are often exaggerated as the YA’s esteemed truths or values collide in some manner.

Another common method of sophistry is to keep truths in isolation rather than see how all truth works in concert,[32] such as emphasizing the truth of agency (as exemplified in the term pro-choice) but isolating it from its tempering truth—the importance of accountability. This is what sophistry of the world often does: it magnifies one virtue or truth to eclipse all others. Therefore, YAs “must [learn to] distinguish between truth and sophistry,” because if they don’t, they may find themselves “believing in the sophistry of man rather than the truth of God.”[33] Elder Andersen recently taught:

Be wise as you balance the doctrine you teach. Give appropriate weight to a point of doctrine within the context of other related truths. Remember the Savior’s counsel about teaching the commandments: “These ought ye to have done, and not to leave the other undone.” Elder Neal A. Maxwell explained, “Gospel principles are weaved together in a fabric which keeps them in check and in balance with each other.” Think of it: God’s love and God’s laws, forgiveness and repentance, the love for God and the love for others, agency and accountability.[34]

Good values, moral principles, and compassionate concerns should not be a playground for manipulation. But YAs need to be aware that many false prophets use proxy issues to manipulate the righteous through sophistry to exchange good for evil, and evil for good (Isaiah 5:20). This is often done through cloaking virtues—good values that are often taken to an extreme until they become an unstable virtue or are used to justify sin.[35] For example, many modern prophets have warned about the dangers of exaggerating one truth, such as mixing up the order of the first commandment to love God and the second commandment to love thy neighbor.[36] Thus a final method to help a YA see through sophistry is to teach them to identify a cloaking virtue. Here is a summary of how many virtues become unstable when they are taken to an extreme or used as a cloaking virtue.

- Enmity of evil used to fight against good. Enmity is a natural dislike and aversion towards something. This is the most common cloaking virtue—using true principles that appeal to mankind’s natural dislike of evil to further something that is ultimately evil. A YA must not only consider clever soundbites of virtue misapplied or overly exaggerated virtues; they must also ultimately know what is evil and what is good, or they may find themselves flattered into fighting against that which is good (see 2 Nephi 28:19–24; Moroni 7:5–19). Considering the ends of the cause, the works of the cause, and where it will ultimately lead is one way to judge: will it lead to eternal life/

Jesus Christ or not? - Using sympathy/

empathy as a shield for scrutiny . This cloaking virtue is employed by some in society who place more value on one’s feelings than on absolute truth. Hypersensitivity should not eclipse other relevant aspects to consider when navigating complex issues. Jesus Christ is “full of grace and truth” (John 1:14; emphasis added). These tempering attributes allow him to comfort a sinner while inviting them to repent. Both grace and truth must be held in perfect balance, neither eclipsing the other. However, a common cloaking virtue today is “not to allow” scrutiny in the name of sympathy.[37] The cry of such a cloaking virtue is, “How dare you uphold a commandment that is offensive and hurting others—you must be a bigoted monster and have no soul!” But truth invites sympathy and scrutiny, charity and clarity. To ignore truth for the “greater virtue” of sympathy is no virtue. - Relativistic circumstances are not an argument against absolute truth. God is the ultimate “arbiter [judge] of truth.”[38] When relative circumstantiality and individualism lead to a rejection of absolute truth rather than a higher manifestation of truth, these virtues have become moral relativism. This can lead a person to believe that rather than discovering truth, an individual creates truth.[39] Elder Christofferson explains, “There are in fact moral absolutes, whether you call them universal human rights or something else. At least some truths and moral concepts exist apart from personal whim or preference. The only debate, really, is what they are and how far they extend.”[40]

- True tolerance versus pseudotolerance. Living by tolerance is truly a principle of God and Zion. However, tolerance can be a cloaking virtue: “The face of sin today often wears the mask of tolerance.”[41] True tolerance does not equate to acceptance; I can be tolerant yet still think that an action is wrong. Therefore, the important questions YAs need to ask are, “What exactly do you want me to be tolerant of?” (identify the object) and “How do you want me to show my tolerance of ____?” (identify the response).[42] If “tolerance” demands that I abandon absolute truth as a response, then it is not tolerance, and it hypocritically defies the championed relativism. Prophets have warned of the dangers of pseudotolerance, a tolerance which equates to moral relativism and an abandonment of eternal truth, or which mocks those seeking to righteously apply true standards to discern good from evil.[43] Finally, tolerance is often demanded but seldom returned. We can keep commandments and keep relationships with those of differing values when mutual tolerance and respect abides.

- Self-government by principles does not preclude eternal law. YAs value their relatively new right of adult autonomy, as well as the right to do things differently from the prior generation. Doing things “different” should not become a point of contention, as we believe very much in teaching correct principles and allowing others to govern themselves.[44] But principle-based living cannot be used as a cloaking argument for anarchy, chaos, or a zero-direction from God—governing oneself does not mean becoming a law to oneself. The very concept of governing, even self-governing, is the appropriate application of laws and truth, not the abandonment of them. Eternal laws operate in and affect our lives, whether we believe them or not.[45] God is the source of our worship, not ourselves or our preferences.

- Social advocacy for rights in the wrong way. Today’s world is full of cloaking virtues that seek to achieve a good end by nasty means. When speaking of recognition of false prophets, the Savior said that some are sheep in wolves clothing but “by their fruits ye shall know them” (Matthew 7:20). Some popular nasty methods we see employed today to bring about “good” include cancel culture, social shaming, extremism, and criticizing diplomatic silence.

- Transparency vs truth in isolation. In the name of transparency, we have been given a more complete picture of the entirety of a story, policy, person, or historical event. For the most part, this transparency and rallying cry for the full truth is a good thing. However, an exaggerated truth in isolation can easily become a lie that can lead into apostasy.[46] For example, to view history from a lens of presentism, where today’s morals are made the jurors of yesterday’s events, is simply arrogance and ignorance in a blender. Isolating truths is not the work of God. He desires an ensemble of all truth, not a soloist. Critical thinking is what the Lord desires, not just criticalness. YAs must learn to reason through tissues and recognize the philosophies of scripture, mingled with TED talks. If YAs won’t disentangle the soundbite or sophistry, or if they won’t analyze the issue in concert with all other truths, they “desire to know the truth in part, but not all” (Doctrine and Covenants 49:2). President Boyd K. Packer likened the fulness of the gospel to a piano keyboard. A person could be “attracted by a single key,” such as a doctrine he or she wants to hear “played over and over again. . . . Some members of the Church who should know better pick out a hobby key or two and tap them incessantly, to the irritation of those around them. They can dull their own spiritual sensitivities. They lose track that there is a fulness of the gospel . . . [which they reject] in preference to a favorite note. This becomes exaggerated and distorted, leading them away into apostasy.”[47] If you tap one key to the exclusion or serious detriment of the full harmony of the gospel keyboard, Satan can use your strength to bring you down.[48]

- Openness to anything vs adapting to new truth. A loving Heavenly Father reveals truth to all his children who are seeking light and knowledge. He does this line upon line, precept upon precept. Therefore, a true disciple is open to new ideas and thoughts and is constantly seeking new truths, experiences, and perspectives. God loves prophets and professors alike; thus some truths come from prophets and some truths come from mankind. However, being open to truth is not being so open that “anything goes.” Nor does a new truth negate or quarantine old truths. Truth builds upon truth; it does not destroy prior truth. Being open to new truth should never be a cloak for accepting everything that is put before you. Conversely, being faithful should never be a cloak for rejecting everything that doesn’t come from general conference. Just as President Nelson found that a heart will continue to beat in a sodium solution due to fixed and eternal laws,[49] there are also laws of society, morality, and goodness that are not canonized. Therefore, it is imperative to acquire the training, experience, and faith to learn from God and man, by study and by faith (Doctrine and Covenants 88:118). A similar principle was taught to Oliver Cowdery when he was told to “study it out in your mind” (Doctrine and Covenants 9:8–9). “Good inspiration is based upon good information.”[50]

- Oversimplifications, false dichotomies, and rewriting the script. Many issues in the Church are often framed as a binary: “it’s either this way or that way.” For example, consider the claim Brigham Young was either a racist bigot or he was a prophet. When the issue is framed in this false dichotomy, one can’t believe both. Similar false dichotomies can be seen in views on polygamy, translation of the gold plates, and the Kirtland Safety Society. The oversimplified argument paints an either-or scenario where one cannot accept the complexity of the situations. However, in many historical and policy scenarios, the truth is often somewhere in the middle of two extremes. When it is framed as a false dichotomy, the truth can never be found without rejecting one extreme in favor of accepting the other. This oversimplification is often the approach of those seeking an agenda that is inconsistent with the contextual complexities of a given situation or policy. The cloaked goal of a person who oversimplifies this way is often to get an otherwise faithful member to rewrite their understanding of history or a policy into an oversimplified script where faith cannot thrive. It is imperative for a PTL to help a YA who is adopting a false dichotomy to realize the binaries by analyzing the two extremes and asking if there could be another explanation, or if the truth could be somewhere in between both extremes. Thus an inquiring person can be free to rewrite their explanatory or reconciliation script, embracing a level of complexity that is nearer to the truth and in which faith can still thrive.

In summary of our discussion on cloaking virtues, society’s exaggeration of a true virtue often paints a picture of a single-attribute God of love. Certainly, God is full of love, but he is also full of truth, justice, knowledge, temperance, diligence, patience, and all good attributes. And often, in a discussion where one virtue of God cloaks or supersedes his other virtues, a person is seeking an agenda that may not be fully in line with the full character of God. Perhaps this is what Jesus meant when he said, “They seek not the Lord to establish his righteousness, but every man walketh in his own way, and after the image of his own god, whose image is in the likeness of the world” (Doctrine and Covenants 1:16). Often what is disguised by an acceptance of all things as a loving collectivism results in hyperindividualism as everyone becomes spiritual in their own way but not collectively religious or righteous.

Conclusion

My teaching and professional assignments have given me the unique experience and blessing of mingling with YAs all over the world. I have taught countless students ranging from the spiritually apathetic to the socially “woke,” from the new and inexperienced convert YAs to some of the most deep-thinking Harvard and MIT YAs seeking intellectual reconciliation with organized religion. My doctoral dissertation was centered around religion and moral reasoning, so I am familiar with how individuals morally reason through issues, especially regarding their religiosity. I have also had the unique opportunity to conduct research and measure learning outcomes for more than fifteen years for the Church, BYU Religious Education, Seminaries and Institutes, and the Missionary Training Centers. I have interviewed hundreds of YAs and read through thousands of responses to surveys and questionnaires. Through all these varied experiences, I have become acquainted with how youth learn, reason, and what they value generally. I can attest to their greatness, and to their vulnerability.

As I have seen a marked shift in YAs’ moral reasoning, I have also noticed a widening gap in the effective communication between some PTLs and some YAs, especially those who differ in their religious orthodoxy. The spiritual “air” that YAs breathe has impacted many of their attitudes about certain ideas and issues, but it has not all been negative. They value many of the very moral principles that will bring about Zion—inclusion, benevolence, equality for all and love and concern for the marginalized. They are defenders and rescuers. Yet, as always, the adversary can make a virtue a vice, if we do not temper it with truth and wisdom. And herein lies our greatest challenge and opportunity as PTLs: to recognize and validate the rightness of their moral instincts while also arming them with the critical thinking skills to avoid being deceived.

As PTLs we have the responsibility not just to pray for them but also to arm them with the tools they need to defend their faith, discern friend from foe, truth from error while being humble enough to learn from YAs. By employing the methods and strategies of disentangling and analyzing, PTLs will be able to help those they love and serve navigate through the unique moral and social challenges of the day with their faith intact. PTLs can equip inquiring YAs with the skills they need to see through subtle sophistry and find peace in the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Notes

[1] Chad Webb, “Cleave Unto the Covenants Which Thou Hast Made” (Ensign College devotional, January 22, 2019), https://

[2] Chad Webb, “Doctrinal Mastery Helps Students with Conversion, Relevance, Belonging,” training video to S&I personnel, August 2021, https://

[3] Isaac Withers, “Why Growing Up with Relativism Has Millennials Searching for New Rules for Life,” This Disorientated Generation no. 5 (2018), https://

[4] See Sheri Dew, “Will You Engage in the Wrestle?” (Brigham Young University–Idaho devotional, May 17, 2016), https://

[5] See Daniel Winder, “Macromorality and Mormons: A Psychometric Investigation and Qualitative Evaluation of the Defining Issues Test-2” (PhD diss., Utah State University, 2009), https://

[6] Winder, “Macromorality and Mormons.”

[7] See Richard G. Scott, “Acquiring Spiritual Knowledge,” Ensign, November 1993, 86.

[8] See Boyd K. Packer, “These Things I Know,” Ensign or Liahona, May 2013, 8.

[9] Withers, “Growing Up with Relativism.”

[10] David A. Bednar, “Seek Learning by Faith,” Ensign, September 2007, 67; emphasis added.

[11] See “Engaging Questions with Our Head and Heart: One on One with Jared Halverson,” April 2, 2020, YouTube video, 9:04, https://

[12] See Neal A. Maxwell, “The Great Plan of the Eternal God,” Ensign, May 1984, 21.

[13] Chad Webb, “His Representatives” (S&I annual training broadcast with President Ballard, January 21, 2022), https://

[14] See Winder, “Macromorality and Mormons.”

[15] John Taylor, “The Organization of the Church,” Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, November 15, 1851, 13:339.

[16] “The Religious Typology: A New Way to Categorize Americans by Religion,” Pew Research Center, August 29, 2018, https://

[17] Bradley R. Wilcox, “Worthiness Is Not Flawlessness,” Liahona, November 2021, 62.

[18] Withers, “Growing Up with Relativism.”

[19] Theodore M. Burton, “The Meaning of Repentance,” Ensign, August 1988, 7.

[20] Some people with complex religious issues are often simultaneously struggling with depression, anxiety, or other forms of mental illness or poor emotional health. This can often obscure their ability to navigate complex issues of faith. Some persons have felt they were numb to feeling the Holy Ghost. Jane Clayson Johnson, Silent Souls Weeping (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 14–18. Some in this state of numbness have left a religious tradition only to find their darkness remained. As they receive professional help, they may find that faith wasn’t ever the issue, but their mental health was. Furthermore, a difficult life event, a loss or failure, or an abusive relationship may create a cavern of emptiness so deep that it eclipses all other factors in a person’s life, including faith. These events can even lead to an identity crisis where a person wonders if they have ever even felt the stirrings of the Spirit or had a relationship with a loving God. And longitudinal studies have shown that feeling judged, identifying crisis events, experiencing guilt, and questioning past experiences are often causes or symptoms of a loss of faith. Many of these difficult issues often require professional help to disentangle faith from mental health. “But the Lord is not limited by mental illness.” See Webb, “His Representatives.”

[21] C. S. Lewis, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1950) 30.

[22] William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (New York: Ongmans, Green, 1920), 196.

[23] Clark G. Gilbert, “The Gospel of Jesus Christ Is Astonishing” (Seminaries and Institutes annual training broadcast with President Ballard, January 21, 2022), https://

[24] “Acquiring Spiritual Knowledge,” in Doctrinal Mastery Core Document (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2022), 2–4.

[25] Dallin H. Oaks, “As He Thinketh in His Heart” (Evening with a General Authority devotional, February 8, 2013), https://

[26] Oaks, “As He Thinketh.”

[27] Dew, “Engage in the Wrestle.”

[28] Jeremy Sutton, “Socratic Questioning in Psychology: Examples and Techniques,” Positive Psychology (blog), June 19, 2020, https://

[29] Sutton, “Socratic Questioning.”

[30] This footnote includes more methods for and further examples of analyzing logic.

Example 1: All organized religion is bad.

Suppose a person claimed that organized religion has done more harm than good for man throughout the years. They use several Age of Imperialism examples that would be considered absolute atrocities in our day: “People conquered whole nations in the name of the Lord.” The assumption behind their claim and the examples is that organized religion is a mask for the power hungry. Their argument is supported by historical examples to show this has sometimes been true. However, a YA and PTL scrutinizing this claim might do the following.

Identify the logic: What is the premise, logic, and conclusion? The premise is that organized religion is created as a means of power and control. The logic is based on selective historical examples. The conclusion is that all organized religion is bad. To help a YA scrutinize the claims, one may ask: Can you make a claim that ONLY SELECTED historical examples logically apply to a conclusion that ALL cases of organized religion are bad?

Analyze assumptions: Is that claim always true? Under what conditions is it true or false? Are their scriptural or other historical examples that go against this claim?

Alternative viewpoints: Are there examples from my own life that refute this claim? Does history always support the claim that all organized religion is for the power hungry? Are there other reasons why organized religions exist? Is the church down the street seeking to conquer nations? If I stacked the good and bad done by organized religion next to each other, what would that look like? For example, for every one person harmed by a religious crusade or imperialistic war, I may find one

thousand orphans or homeless persons clothed and fed by organized religion.

Paradigm shift: Do you want to revise your claim? What would make your claim more true?

Example 2: Agency and abortion.

A young person makes an argument that agency is so important to God and although they would never seek an abortion, they feel that man’s laws should not limit a woman’s right to choose to have an abortion.

Identify the logic: Agency is extremely important to God. God gave humans agency. Conclusion: THEREFORE, the Church should be OK with a choice to have an abortion.

Analyze assumptions: Identify that there is a faulty premise and understanding of the purpose of agency. Agency is being used as a right to sin. The student misunderstands and supposes that agency is the right to do whatever they want to do without regard to anyone but themselves and is dismissive of eternal consequences.

Socratic questions: What is the purpose of agency? What is the difference between agency and anarchy? Is agency permission to sin or is it something more? Is the freedom to choose the definition of agency, or is it a condition of agency? What are other premises/

Scenarios and extreme hyperbole: Suppose someone wanted to use their agency to hurt you—would God condone or condemn that? For example, what would happen if agency was used by ______ for permission to sin that hurts others (fill in the blank with thieves, pedophiles, or businesspersons)? Suppose agency was used to justify any sin—what might happen? How would agency destroy itself in this scenario?

Scriptural examples: What did Lehi teach in 2 Nephi 2 that helps us understand that agency has several assumptions to fully exercise it as a principle of the gospel?

Paradigm shift: Should you adjust your understanding and application of agency? What are some tempering truths to understanding agency and the freedom to choose? How do you feel about adjusting your understanding of the purpose of agency?

[31] Henry Ford, My Life and Work (New York: Doubleday, 1923), 247.

[32] See Packer, “The Only True and Living Church,” Ensign, December 1971, 40; and Dallin H. Oaks, “Our Strengths Can Become Our Downfall” (Brigham Young University devotional, June 7, 1992), speeches.byu.edu.

[33] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Be Not Afraid; Only Believe” (Church Educational System fireside, September 15, 2001), https://

[34] Neil L. Andersen, “The Power of Jesus Christ and Pure Doctrine” (S&I Broadcasts, June 11, 2023), https://

[35] See Quentin L. Cook, “A Banquet of Consequences: The Cumulative Result of All Choices” (Brigham Young University devotional, February 7, 2017), speeches.byu.edu; Thomas S. Monson, “Examples of Righteousness,” Ensign or Liahona, May 2008; Dallin H. Oaks, “Two Great Commandments,” Ensign or Liahona, November 2019; Packer, “Only True and Living Church”; and Packer, “These Things I Know,” Ensign or Liahona, May 2013.

[36] Scott Taylor, “Elder Christofferson Calls on ‘Best of Gen Z’ to Avoid Traps of Generation’s Generalizations,” Church News, September 1, 2021, https://

[37] Taylor, “‘Best of Gen Z.’”

[38] Nelson, “Love and Laws of God.”

[39] Spencer W. Kimball, “Absolute Truth” (Brigham Young University devotional, September 6, 1977), speeches.byu.edu.

[40] D. Todd Christofferson, “Truth Endures,” Religious Educator 19, no. 3 (2018): 5.

[41] Monson, “Examples of Righteousness,” Ensign or Liahona, May 2008, 65.

[42] Packer, “Be Not Afraid” (address at the Ogden Institute of Religion, November 16, 2008), 5.

[43] See Nelson, “What Is Tolerance?,” New Era, March 2011, 2–4; Dallin H. Oaks, “Judge Not and Judging” (Brigham Young University Devotional, March 1, 1998), speeches.byu.edu; Packer, “These Things I Know,” Ensign or Liahona, May 2013, 6–8; and Bruce D. Porter, “Defending the Family in a Troubled World,” Ensign, June 2011, 12–18.

[44] See Taylor, “Organization of the Church,” 339.

[45] Nelson, “Love and Laws of God”; and Taylor, “‘Best of Gen Z.’”

[46] Packer, “Only True and Living Church.”

[47] Packer, “Only True and Living Church,” 42.

[48] Oaks, “Our Strengths.”

[49] See Sheri Dew, Insights from a Prophet’s Life: Russell M. Nelson (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019).

[50] Nelson, “Revelation for the Church, Revelation for Our Lives,” Ensign or Liahona, May 2018, 94.