The Story of the Restoration Continues

Insights into Saints, Volume 2

Matthew J. Grow, Scott Hales, Lisa Olsen Tait, Angela Hallstrom, and Jed Woodworth

Matthew J. Grow, Scott A. Hales, Lisa Olsen Tait, Angela Hallstrom, and Jed Woodworth, "The Story of the Restoration Continues: Insights into Saints, Volume 2," Religious Educator 21, no. 3 (2020): 25–43.

Matthew J. Grow (mjgrow@churchofjesuschrist.org) was managing director of the Church History Department and a general editor of Saints when this was published.

Scott A. Hales (scott.hales@churchofjesuschrist.org) was the lead writer and literary editor for Saints when this was published.

Lisa Olsen Tait (lisa.tait@churchofjesuschrist.org) a historian/writer and volume editor on Saints, Volume 2 when this was published.

Angela Hallstrom (angela.hallstrom@churchofjesuschrist.org) was a writer on the Saints project when this was published.

Jed Woodworth (jlwoodworth@churchofjesuschrist.org) was managing historian of Saints when this was published.

Saints is about experience, the complex, messy, difficult, beautiful experience of the human condition made sacred as we see the hand of the Lord in the midst of life.

Saints is about experience, the complex, messy, difficult, beautiful experience of the human condition made sacred as we see the hand of the Lord in the midst of life.

The following remarks were presented in a panel discussion of Saints, Volume 2: No Unhallowed Hand in the auditorium of the Joseph Smith Building on Brigham Young University campus, 21 February 2020.

A Brief Introduction to Saints, Volume 2: No Unhallowed Hand

Matthew J. Grow

On 12 February 2020, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints released the second volume in the Saints series. Subtitled No Unhallowed Hand, this volume begins with the Latter-day Saints leaving Nauvoo, Illinois, in early 1846, shortly after thousands of Church members received their endowments in the partially completed Nauvoo Temple. It tells the story of the settlement of territorial Utah and the surrounding areas; the expansion of missionary work around the globe, with a particular emphasis on Europe and the Pacific; the gathering of Saints to the American West; the lived reality of plural marriage and the national campaign to end it; and the expansion of temple work. The volume covers almost half a century and ends with the amazing spiritual experiences that accompanied the long-awaited dedication of the Salt Lake Temple in 1893. We are thrilled that this volume is now in the hands of Latter-day Saints around the world.

Those of us who have the privilege of being involved in the Saints series were astounded by the reception of volume 1. Released in September 2018 in fourteen languages, The Standard of Truth has been well received by Latter-day Saints around the globe. It is difficult to precisely gauge the number of Saints who have read Saints, but the reception has been well beyond anything we envisioned. Over 500,000 print copies have been sold, with 30% of those being in languages other than English. The electronic usage has outpaced the print usage, with well over 100 million chapter views and 30 million chapter listens (volume 1 has forty-six chapters) on the Gospel Library App, the Church’s website, and other electronic means.

The reception indicates that the product met the moment. Latter-day Saints around the globe need an accessible and faithful history that explains our collective past in ways that would allow us to draw inspiration and strength from members of the early Church. Two more volumes will bring the story even closer to the present. Volume 3: Boldly, Nobly, and Independent, will tell the story of the Church in the first half of the twentieth century and end with the dedication of the Swiss Temple in 1955. This milestone was significant for the Church as it was the first temple dedicated in an area without large numbers of Latter-day Saints. The final volume, Sounded in Every Ear, will narrate the Church’s globalization since that time. Its cover will feature temples built in Sao Paulo, Brazil; Hong Kong; and Accra, Ghana, symbolic of the fact that temples now dot the earth. We anticipate that there will be a gap of 18–24 months between the publication of each volume.

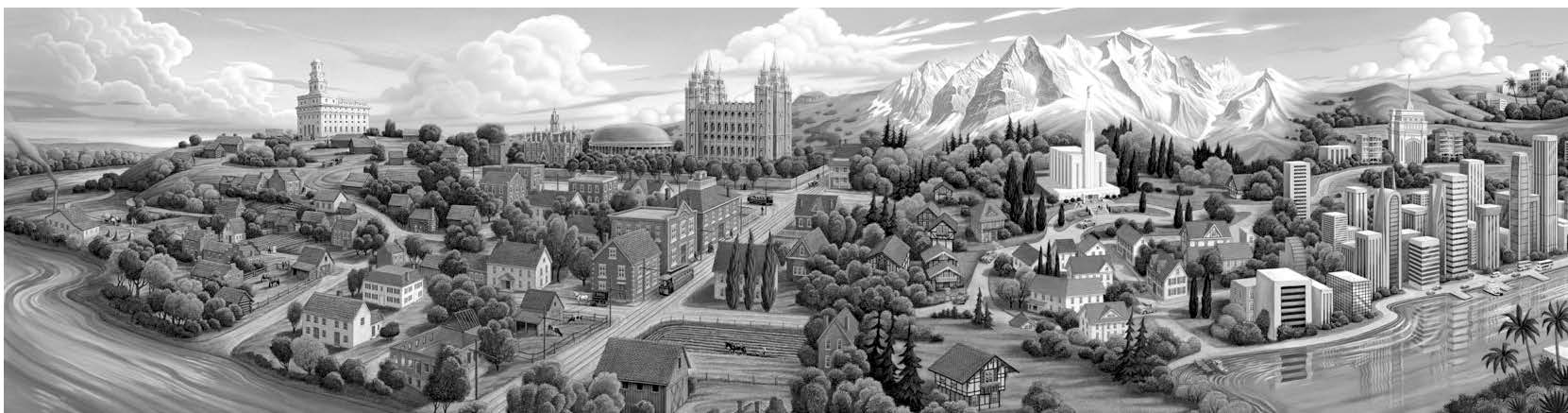

When the set is complete, the images on the spines of the books will blend together to show one great panorama of the Church’s past from the Nauvoo temple to our current era. We hope the books will function in the same way to help Latter-day Saints not only understand the stories of individuals but also understand how Church history fits together to form a panorama of faith, with a central theme of temples.

The Saints project began roughly a decade ago. The contributions that follow in this forum illustrate the dynamics of that team. First, we have a team of historians, represented here by Jed Woodworth and Lisa Tait. Assisted by others, their task is to find compelling historical stories, to understand those stories in various historical contexts, and to ensure that everything published in Saints is historically accurate. Second, we have a team of creative writers, represented here by Scott Hales and Angela Hallstrom. Their task is to take the stories from the historians and write them in a narrative style that readers will find accessible and engaging. The Saints project succeeds because of the blending of the historical and the literary.

The combined panorama of the books’ spines highlight the theme of temples. The four covers of the volumes of Saints continue that theme.

The combined panorama of the books’ spines highlight the theme of temples. The four covers of the volumes of Saints continue that theme.

Though not represented here, many others work on the Saints project to ensure its success. We have a team of editors who provide substantive editing and copyediting, advocating for the reader in making the writing as accessible as possible. Source checkers assist in this process by double- and triple-checking each historical source to ensure accuracy. A team of reviewers throughout the world—writers, historians, interested Church members, staff members in various Church departments, members of the presidencies and boards of the Church’s general organizations, and more—give feedback throughout the process. All of this takes place under the guidance of General Authorities, including the Church Historian and Recorder (Elder LeGrand R. Curtis Jr.), members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and the First Presidency. These Church leaders likewise scrutinize the text closely, make recommendations, and approve the final content of each volume. In a message published at the beginning of the series, the First Presidency states, “We pray that this volume will enlarge your understanding of the past, strengthen your faith, and help you make and keep the covenants that lead to exaltation and eternal life.”

In writing the Saints series, we have been particularly hopeful that it would be useful to religious educators and their students. We hope that the volumes and the online supplemental material are helpful to students in two ways. First, we know that the rising generation of Latter-day Saints has to face an unprecedented onslaught of negative information about Church history and doctrine. Of course, this information is not new; each generation of Latter-day Saints has had to grapple with key questions of the nature of revelation, prophets and miracles, gold plates, and plural marriage. But the digital age has enabled the delivery of challenging information, often presented in the worst possible light, on a much greater scale. Saints tackles challenging information by placing it in its appropriate context, not by pursuing the false choices of either minimizing it or dwelling on it. So, for example, students will learn in volume 2 about plural marriage by reading the stories of Latter-day Saints who felt called to live a principle that modern Saints find challenging. They will come to know the perspectives of these earlier Saints who faced new family circumstances as well as ridicule and political pressure from the broader world. And they will accompany President Wilford Woodruff and other Church leaders as revelation to President Woodruff guided the end of the practice of plural marriage.

Second, and most importantly, we hope that Saints is useful to students by introducing the lives of Latter-day Saints in the past to inspire Latter-day Saints today. The most important decision when writing a history is what to include and what to exclude. We decided early on that this will be a “small plates” history. We looked to Latter-day Saint scriptures as a guide. We know that the Book of Mormon record keepers kept both large plates and small plates. Nephite record keepers used the large plates to record political and military history; they used the small plates for the “the things of God” that were “most precious,” including “preaching which was sacred, or revelation which was great, or prophesying.” The small plates were recorded “for Christ’s sake, and for the sake of our people” (1 Nephi 6:3; Jacob 1:2, 4). Saints is a “small plates” history that narrates the sacred history of the Church. Crucially, it does this through the stories of individuals so that Latter-day Saints today can identify and find strength in the ways that our predecessors have lived the gospel of Jesus Christ, notwithstanding the many challenges they faced.

We hope that you and your students will benefit greatly from Saints, Volume 2: No Unhallowed Hand—and that you will eagerly anticipate the next two volumes that will tell the little-understood story of how the Church of Jesus Christ has spread throughout the world.

“Write in a Narrative Style”: Saints and the Power of Story

Scott A. Hales

Saints is somewhat unique among history books. The four-volume series is a work of narrative history, which means it relies on traditional storytelling techniques to relay information about the past. But unlike many works of narrative history, which similarly draw on these techniques, Saints aspires to be almost novelistic in style—while still remaining a work of nonfiction. We designed the series this way on purpose. We knew that many readers, particularly younger readers, would be more likely to read a history book if it had a good story.

As we note in the introduction to volume 1, Brigham Young instructed Church historians in 1861 to “take a different Course in writing Church History.” “Write in a narrative style,” he advised them, and “write only about one tenth part as much.”[1] We don’t know why President Young made this request. But as his many sermons attest, he was an extraordinary storyteller who understood that true, well-told stories have a powerful effect on audiences. Indeed, by asking Church historians to “write only about one tenth part as much,” he was not asking them to conceal or cover up our history, as some might assume. Rather, he was teaching them a foundational principle of storytelling: cut extraneous details and get to the heart of the story, where its true power to change hearts and inspire minds resides.

We often see the power of storytelling in Church meetings. Think about how often Church leaders share stories in general conference. Often the most memorable talks are those with simple, short stories that illustrate a gospel principle. The same is true in the scriptures themselves. There’s a reason why most readers enjoy 1 Nephi more than 2 Nephi—and it’s not because 1 Nephi comes first in the Book of Mormon. Both books are by the same author, and both teach vital gospel truths. But the fact that 1 Nephi embeds these truths in an interesting, carefully crafted story makes all the difference. Nephi’s story—his primal journey—draws us in, leading us like an iron rod to the word of the Lord, in a way his long quotations of Isaiah in 2 Nephi are unable to do. We remember that Nephi said, “I will go and do the things which the Lord has commanded” (1 Nephi 3:7), because it is a key piece of dialogue at a pivotal moment in the story of Nephi and his brothers returning to Jerusalem to get the brass plates.

In 1898 another Nephi articulated the power of purposeful storytelling in an article for the Improvement Era. Unconvinced by arguments that stories were too light and frivolous for youth, Latter-day Saint novelist Nephi Anderson reasoned that stories—even highly entertaining ones—were in fact effective teaching tools. “The Latter-day Saint understands that this world is not altogether a play ground,” he wrote, “and that the main object of life is not to be amused.” Yet, he noted, a story writer “reaches the people” and “should not lose the opportunity of ‘preaching.’ . . . A good story is artistic preaching.”[2]

Anderson applied this principle of “artistic preaching” in his own writing, including his most enduring work, Added Upon (1898), an ambitious novel that uses traditional storytelling techniques to teach the plan of salvation.[3] Though much of his writing was fictional, Anderson also used “artistic preaching” in his nonfictional work, most notably in A Young Folks’ History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (1889, 1917), which was used for many years as a textbook in the Sunday School. I see A Young Folks’ History of the Church as a kind of intellectual and stylistic precursor to Saints for the way it used simple, clear prose and storytelling to teach readers about the Restoration and instill in them “a love for its heroes, a loyalty to its principles, and an appreciation of its achievements.”[4]

In crafting true stories about the Restoration in order to help readers “prize more highly that heritage given them of God,” Anderson understood that stories build communities.[5] In a New York Times article entitled “The Stories That Bind Us,” columnist Bruce Feiler argues that creating a strong narrative is vital for any community or family hoping to succeed. Drawing on the research of psychologists who work with children and families, Feiler notes that “the more children knew about their family’s history, the stronger their sense of control over their lives, the higher their self-esteem and the more successfully they believed their families functioned.” Knowing their shared history, moreover, helped individuals develop an “intergenerational self” that helped them feel like “they belong to something bigger than themselves.”

Feiler also quotes Dr. Marshall Duke’s observation that “the most healthful narrative” is “the oscillating family narrative,” which he characterizes as follows:

We’ve had ups and downs in our family. We built a family business. Your grandfather was a pillar of the community. Your mother was on the board of the hospital. But we also had setbacks. You had an uncle who was once arrested. We had a house burn down. Your father lost a job. But no matter what happened, we always stuck together as a family.

Ultimately, for Feiler the strongest families are those that “create, refine and retell the story of [their] family’s positive moments and [their] ability to bounce back from the difficult ones.”[6]

Like the first volume in the series, Saints, Volume 2: No Unhallowed Hand is an “oscillating narrative” about the family of God, which we hope will help Latter-day Saints today develop “intergenerational selves.” As such, it is not always an easy story. In this volume, we see two generations of Latter-day Saints rising and falling and rising again as they struggle to “[put] off the natural man and [become] Saint[s] through the atonement of Christ the Lord” (see Mosiah 3:19). Some stories uplift the readers’ spirits. Others harrow their souls. Yet, by the end of the volume, their faith is stronger—and the Church is stronger—for having made the journey.

Perhaps the most difficult and painful chapter in volume 2 deals with the Mountain Meadows Massacre. The narrative owes a great deal to Ronald W. Walker, Richard E. Turley, Glen M. Leonard, and other Latter-day Saint historians whose groundbreaking work on the massacre has given scholars greater insight into what happened on 11 September 1857. We hope our narrative will help even more readers understand this tragedy and learn from the errors of those who carried it out. I recently spoke with a reader who said she was horrified after reading the Mountain Meadows chapter because the massacre was far worse than she had imagined. At the same time, though, she was grateful for the knowledge she had gained from the narrative. Before, the massacre had been a mystery to her. Now, thanks to the narrative, she had answers.

Saints is designed for such readers, and story is the universal language we use to reach them. Screenwriter and story theorist Robert McKee has said that a “culture cannot evolve without honest, powerful storytelling.”[7] I believe the same is true for Zion. We need a family story—now more than ever. In their endorsement of Saints, the First Presidency reminds us that we are “an important part of the continuing history of this Church.” Without each individual effort to build Zion and live by its principles, the Church cannot move forward. Our shared narrative reminds us why we labor for Zion and its future.

True stories matter. We hope Saints, Volume 2 continues to enlarge our understanding of what it means to be the family of God. Such an understanding is key in becoming “of one heart and one mind” in the great latter-day work.

Experience Bearing Witness

Lisa Olsen Tait

When I am asked what led me to become a historian, my response is simple: people. I am interested in people, in their experiences, in the human condition. In my view, and I believe many readers agree, what makes Saints so powerful is that we experience history from the point of view of individual people.

Biblical scholar Peter Enns has noted that the Bible is “the story of God told from the limited point of view of real people living at a certain place and time.” Moreover, he points out, “God lets his children tell the story.”[8] The same could be said of Church history. It is the story of the Lord’s hand in the lives of his children—told by those children, from their human point of view. The Lord has commanded us to tell the story, but he has not given us a detailed outline for how to do it, except that, as the revelation in Doctrine and Covenants 21 says, our sacred history is to bear witness of his hand in the rise and progress of the Church (see Doctrine and Covenants 21:1).

When Joseph Smith was in Liberty Jail, the Lord told him, “Know thou, my son, that all these things shall give thee experience” (Doctrine and Covenants 122:7). It has always been interesting to me that the revelation doesn’t say what kind of experience, and it doesn’t explicitly tell him what he is supposed to learn from that experience (not everything, anyway). Experience is presented as a primary purpose of this life and a primary good in and of itself.

Saints is about experience. By reading stories told from the perspective of participants, we share in their experiences—we identify with them. And we see that what we now call “history” was simply “life” to those who experienced it. Just as we struggle through each day with limited perspective and partial understanding, so did they. This is a powerful perspective to help people develop, especially in regard to figures who might be seen as larger than life.

While we did not seek to cut anyone down to size, so to speak, we did set out to reflect their essential humanity. This means that in many cases, readers will come to know high-profile people in new and sometimes surprising ways. We see Brigham Young wading in the mud to help people move their wagons forward, looking “happy as a king.”[9] We see him as a father: taking his young asthmatic daughter into his arms, telling her to “take time to breathe” and later bearing his testimony to her in unforgettable terms.[10] Many readers will have heard of Joseph F. Smith’s mission to the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) when he was only fifteen years old, but in Saints we experience that mission through his letters to his sister.[11] We also learn about his complex family arrangements and the heavy burden he and the other leading brethren carried as the antipolygamy crusade gained steam. Eliza R. Snow is another towering figure in Church history, known as both “prophetess” and “presidentess” and undisputed leader of all Latter-day Saint women’s work. And yet when Brigham Young first called her to publicly “instruct” the women of the Church, she felt nervous at the prospect. “My heart went ‘pit a pat,’” she recalled. “I did not, and could not then form an adequate estimate of the magnitude of the work before me.”[12] Saints shows some of the magnitude of the work done by Eliza and so many other women in the development of the extensive network of women’s organizations and relationships that was such a vibrant part of this era.[13]

Other people in this volume were prominent in their time but may be less well known today. George Q. Cannon is one of my favorite people in this category. When the book begins, Cannon is still a young man in his twenties. We see him serve a mission to the gold fields in California (how many people know there were missionaries sent to the gold fields in California?) and from there he goes to Hawaii, where he receives a gift of tongues and eventually helps translate the Book of Mormon into Hawaiian for the first time. But that’s only the beginning of Cannon’s story, which takes him to Washington, D.C., and back to Utah; he is called to the Quorum of the Twelve and eventually becomes one of the First Presidency. He even does some time in prison, and at one point he falls off a moving train![14] Cannon’s statement in general conference when the Manifesto was announced is one of the most powerful reflections we have of the humanity and experience of our leading brethren. “The presidency of the Church have to walk just as you walk,” he said. “They have to take steps just as you take steps. They have to depend upon the revelations of God as they come to them. They cannot see the end from the beginning, as the Lord does.” They can only seek revelation and then act upon it when it comes.[15]

Another person in this category is Susa Young Gates. She may not be entirely unknown, but the book brings her to life: as an asthmatic child, an accomplice in her sister’s elopement, a devastated young mother experiencing a harrowing divorce. We see her rebuild a happy second marriage, serve a mission in Hawaii with her husband, and start the Church’s young women’s magazine. She uses her knowledge of shorthand to take official minutes at multiple temple dedications, and she becomes the first woman to be baptized for the dead in the St. George Temple, beginning her lifelong service in the temple.[16] “My whole soul is for the building up of this kingdom,” she wrote.[17] Readers will get many glimpses into her soul and come to love her as one of the main characters in the book.

Finally, of course, there are the many people who will likely be entirely new to readers: Augusta Dorius, who comes to Utah by herself as a fourteen-year-old girl after joining the Church in Denmark;[18] Ida Hunt Udall and Lorena Washburn Larsen, who made heart-wrenching sacrifices and lived in extremely difficult circumstances as plural wives on the “underground”;[19] Jonathan Napela, an early convert and Church leader in Hawaii who worked with George Cannon on the translation of the Book of Mormon and later moved to the leper colony on Molokai with his wife;[20] and Samuel Chambers, who was born into slavery, joined the Church at the age of thirteen while still enslaved, and eventually made his way to Utah with his wife Amanda, where they became stalwart members of the Salt Lake First Ward despite the policies of the time that denied them full participation because of their race.[21]

While we refer to these people as “characters” in the book, we hope readers will come to know them as people. There is something sacred about seeing the world through another person’s eyes. Saints is about experience—the complex, messy, difficult, beautiful experience of the human condition—made sacred as we see the hand of the Lord in the midst of life. This is what makes it a “faith-promoting” history, not because we have created a narrator that tells you what to think about everything but because we have let people’s experience speak for itself. And when that experience does speak, it bears witness.

The Power of Diverse Perspectives in Saints

Angela Hallstrom

Lisa Olsen Tait just described one of the great strengths of the Saints series: the variety of compelling and relatable people whose stories we tell. As a writer on the Saints project, highlighting this array of diverse voices is one of my most important tasks, but it is also one of my most challenging. The historians and writers on our team frequently grapple with difficult questions: Whose stories do we choose to highlight? How do we find and use the source material we need to foreground underrepresented perspectives? What methods can we use to keep readers’ attention while we hop around the globe, from one point of view to another? These questions became more urgent as we moved from volume 1 to volume 2 of Saints and the scope of the story broadened.

“Whose stories do we choose to highlight?” is arguably the most crucial question our team confronts. Historians must ensure that the book emphasizes critical developments in the Church’s evolving story, and writers must ensure that the story is engaging enough to keep our readers turning the pages. We also feel a real responsibility to capture the breadth and depth of Church history: we want to be in Samoa and in Salt Lake City, in Missouri and in Mexico, telling the stories of famous Church leaders alongside those of everyday Latter-day Saints.

In volume 2 many scenes are set in and around Utah Territory, since that is where the majority of Latter-day Saints lived at the time. But we did not want to forget the essential stories unfolding in places like Denmark, England, French Polynesia, South Africa, Norway, and New Zealand. Our history also would have been incomplete without the voices of African American Saints, Native American Saints, and members of the Church who immigrated to Utah from Europe, the South Pacific, and other areas.

Stories that take place outside Utah are among the most compelling in the volume. In Hawaii we follow the youthful George Q. Cannon, Joseph F. Smith, and Susa Young Gates as they do missionary work, but we also see how Jonathan and Kitty Napela’s local leadership lays the foundation for the Church to thrive in the Pacific.[22] Some faithful Hawaiian Saints immigrate to Utah and establish a settlement called Iosepa, and we rejoice with them when they attend the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple in the book’s final chapter.[23] Hawaii as a setting also gives us one of the great villains of volume 2 in the duplicitous Walter Murray Gibson, who tries to establish his own “empire” in Lanai.[24]

The story of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation is powerful as well. In Saints we see the suffering that Native Americans endured after white settlers took possession of the land, including the horrific Bear River Massacre that decimated the Northwestern Shoshone. When a Shoshone leader named Ech-up-wy has a vision telling him to seek out the Latter-day Saints, another leader named Sagwitch believes him. Sagwitch then asks a local Latter-day Saint missionary to teach the members of his band, and over one hundred people are baptized in one day, including Sagwitch. These Shoshone Saints go on to become faithful members of the Church, assisting in the construction of the Logan Temple and performing ordinances for ancestors who died in the Bear River Massacre.[25]

Including the perspectives of well-known Church leaders is also crucial to our storytelling. A character like the apostle George Q. Cannon has a lot to offer Saints writers: not only does his leadership position put him in the middle of the action during pivotal historical events, but his exhaustive journal is filled with interesting details and personal ruminations that help the story come alive. Take, for example, Cannon’s description of the first time he heard Wilford Woodruff mention that plural marriages should no longer be performed in Utah Territory. Not only does his journal entry give Saints writers a setting where an important conversation about plural marriage can unfold—the discussion happens over dinner with a stake president in Farmington, Utah—but Cannon’s candor provides emotional texture to the scene. He recounts that when President Woodruff asked his opinion on halting further marriages, he was too dumbfounded to speak.[26] “I was not prepared to fully acquiesce in his expressions,” Cannon writes, “for, to me, it is an exceedingly grave question, and it is the first time that anything of this kind has ever been uttered, to my knowledge, by one holding the keys.”[27]

George Q. Cannon’s journal is readily available for Church historians’ use. In fact, it is available for anyone with access to the internet, published by the Church Historian’s Press at https://

One way Saints writers emphasize characters who have not left a robust personal record is to mine other sources that allow us to flesh out that character’s scene. One example is Samuela Manoa, a Hawaiian member of the Church who served as a missionary to Samoa. Manoa was sent to Samoa by Walter Murray Gibson—the duplicitous villain mentioned earlier. Manoa and his companion were successful in baptizing around fifty Samoans, but Church leaders had not authorized Gibson to send missionaries to Samoa and had no idea Manoa and his companion were there. Manoa ended up living in Samoa for twenty-five years, patiently waiting to hear from Church headquarters, until additional missionaries finally arrived in 1888.[28] Samuela Manoa did not leave behind a record like George Q. Cannon’s. However, he told his story to missionaries who worked alongside him in Samoa, who then wrote his story in their own personal accounts as well as in the Manuscript History of the Samoan Mission. Rather than tell Manoa’s part of the story from the perspective of the missionaries—the original authors of our sources—we made sure that Manoa, who played such a pivotal role in early Samoan Church history, was foregrounded in the scene.

Work done by family historians has also allowed us to tell compelling stories of everyday Saints. For example, Ida Hunt Udall and Lorena Washburn Larsen are two women who help Saints readers understand the complexities of plural marriage in the 1880s.[29] Mormon Odyssey: The Story of Ida Hunt Udall, written by Maria S. Ellsworth, Udall’s granddaughter, allowed Ida’s story to receive wider attention and proved to be an invaluable resource.[30] Loretta Luce Evans, the great-granddaughter of Lorena Larsen, and other Larsen family members compiled and published Larsen’s history and donated it to the Church History Library.[31] Our team would not have known Lorena’s story without her family members’ efforts to preserve it and make it available.

With so many important stories to tell, one of the most difficult decisions Saints writers face is which ones to leave on the cutting room floor. While we would love to tell as many stories as possible, our books have a set length, and readers’ attention only stretches so far. Deciding which stories to highlight has only become more challenging as our team works to write the history of a growing, international Church in Saints, volume 3 (1894–1954) and Saints, volume 4 (1955–present day). We constantly balance the desire to include as many voices as possible with the reality that, if we try to do too much, we risk confusing or overwhelming our readers.

Over time, the Saints team has developed a checklist that helps us narrow down material to find the best fit for the project: Does this story show important change in the Church over time? Is it dramatic, delightful, or compelling? Is there a sacred or spiritual aspect to the story? Is it told from an interesting point of view or from a perspective that needs to be represented? Does the source material offer details, descriptions, and personal reflections that can flesh out a scene? Can we return to this character multiple times in the narrative? Not every character or story we choose fits each of these criteria, but many of them do, and we think that Saints is richer for it.

The writer Peter Forbes says, “We tell stories to cross the borders that separate us from one another and to help us imagine the world—past, present, future—differently.”[32] There are still so many Latter-day Saint voices that need to be heard. The stories that the Saints team has considered but cannot include barely scratch the surface of the powerful narratives that remain untold. It is my hope that Saints becomes just one example among many of an explosion in narrative writing by and about Latter-day Saints—writing that helps us understand not only our past and our predecessors, but ourselves and our future.

The Difficult Stories

Jed Woodworth

The stories we have heard earlier are largely happy stories. These are the kind of stories we often hear in fast and testimony meeting, the ones that have a clear, satisfying ending, or that build faith in an obvious way. But we all know there are other kinds of stories. These are the ones that end, at least temporarily, in heartache or pain or without clear resolution. These are the difficult stories. I would like to say a few words about three types of difficult stories in Saints, volume 2—plural marriage, violence, and race.

Why do we include such stories? Why not include only stories with happy endings?

The second volume in the Saints series covers over half a century and ends with the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple in 1893.

The second volume in the Saints series covers over half a century and ends with the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple in 1893.

One reason is that if we were to omit the difficult stories, we would be introducing distortion into our account of the past. Not every story ends like a Disney movie. Not everything can be “sweetness and light.”[33] The plan of salvation teaches that we were sent to earth to confront, not avoid, good and evil, happiness and misery (see 2 Nephi 2:10–13). The difficult stories reflect life as it actually is and not just as we would like it to be. They add depth to our awareness. They force us to take account, to reckon, to grapple. They may require us to search, ponder, and pray. Without the difficult stories, we run the risk of turning the past into a mere caricature, a cartoon. The growth we might have had from seeing things “as they really are” does not occur (Jacob 4:13).

The Lord does not avoid difficult, morally ambiguous stories. Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac, Rahab’s assistance to the Israelites, and Peter’s denial of the Christ all challenge the airtight moral categories we all too easily create for ourselves. Tellingly, the Lord says the Doctrine and Covenants is a place where the “erring” of the Saints is to be made known. “And inasmuch as they sinned they might be chastened, that they might repent” (Doctrine and Covenants 1:25, 27). Saints does not take for itself the task of correction. It does not seek to chasten or condemn. Insofar as past historical actors experienced erring or sin in their lives, however, the book takes no pains to avoid this.

The transparent style is useful for times like ours. We know that in the internet age, hiding troubling pieces of the past is a losing strategy. Often against our will, we are bombarded by all sorts of information, some of it accurate, much of it not.[34] Sooner or later, young people living in today’s world will encounter uncomfortable truths about the past. Better for the institutional Church to explore these uncomfortable truths than to leave the rising generation to wander without guidance. Even where error or sin is made known, the Lord promises that the humble will be given strength (see Doctrine and Covenants 1:28).

The difficult stories also challenge our own stereotypes about the past. If we think plural marriage was all good, that plural families always existed in a harmonious state, the stories of Ida Hunt Udall and Lorena Larsen in volume 2 show us that life in the practice could be lonely and isolating. But if we think plural marriage was all bad, we find that little Susa Young grew up happily in a household with dozens of brothers and sisters and that future leaders like Susa and Heber J. Grant would never have been born were it not for plural marriage. For all the difficulties Udall and Larsen encountered in plural marriage, they also found solace in the children they bore and in the assurance that they had done God’s will by entering into the practice.

Likewise, if we suppose that the Saints were always welcoming and inviting to Native Americans, the “war of extermination” in Utah Valley, in which Latter-day Saints killed dozens of Ute Indians in 1850, dispels this myth. But if we think the Saints were just as ruthless as others on the frontier, volume 2 asks us to think again. Brigham Young smokes the peace pipe with Native peoples, and Saints like Bishop Peter Maughan provide flour and food stuffs to starving Shoshone Indians of Cache Valley. The Saints could never believe, as many Americans did, that Native peoples were destined for extinction. To the contrary, nineteenth-century Saints believed that Native peoples came from covenant lineage and thus had a vital role in the plan of salvation in the latter days.

Difficult stories teach that human frailty is real. They remind us that no one is immune from the wages of sin. In the case of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, otherwise godly Saints spiraled quickly downward into greed, lying, and murder. In later accounts of this event, the urge to protect the Church from shame and recrimination caused Latter-day Saints to cover up the involvement of our people in the massacre. Not until relatively recently, after acknowledging our wrongdoing, did the process of public reconciliation with descendants of the massacre and private reconciliation within ourselves as a people begin. The detailed account of the massacre found in volume 2 moves us further in the direction of accountability and thus healing.

Ironically, Mountain Meadows is a scandal that leads us back to Christ, the ultimate source of healing. It teaches us how desperately we need the Lord’s atoning sacrifice for sin—and a power higher than our own to keep us in the right way. “Our darkest day as a people,” Patrick Mason has observed, “becomes a means by which we can turn back to Christ and enhance our discipleship, even though of course it would have been better for the sin to remain undone.”[35]

In other words, Saints disrupts the simple conceptions we might have about the past. Life is complicated. People are complicated. To make sense of the past, we need access to a full range of actions and behavior. Somewhat unsettlingly, volume 2 reminds us that the past does not always speak in our own language or play by our own rules.[36]

The difficult stories are or can be, in their own way, stories of faith. For believers like us, there is a moral tilt to the universe. Because of Christ, things ultimately move in the direction of reconciliation, peace, and rest (see Moses 7:63–65). Consider, for example, the African-American pioneer Jane Manning James. Over the course of decades she requested, but was denied, the temple endowment because of the color of her skin. By any measure, this is a painful story. But the fact that Jane persisted in the Church and its activities despite this pain is inspiring in its own way. Jane’s story has something to teach us. The Church is worth serving, worth loving, worth trying to improve, even when things are not ideal.

Most of us like stories that are tidily resolved. But some of the difficult stories in volume 2 ask us to take the long view, to receive the prophets “in all patience and faith” (Doctrine and Covenants 21:5). Some of the stories are not resolved for decades. Some will not be resolved until after we die. In the case of Jane James, the resolution really does not come until 1978, when priesthood and temple blessings are extended to people of every race.

Not every difficult story will have a discernable moral outcome. Some things in life are inexplicable. We don’t know why God permits some old people to linger in pain rather than die quickly and be reunited with their loved ones. We don’t know why some infants are taken in childhood. Challenging events like these put us in the position of Job, testing our faith in God’s goodness. And so it is with the history of the Church. Not everything will be easy to digest. Some things just have to be taken on faith. We, not the historical actors we are reading about, are the ones who are being scrutinized.

Notes

[1] Wilford Woodruff, Journal, 20 October 1861, Church History Library.

[2] Nephi Anderson, “Purpose in Fiction,” Improvement Era, February 1898, 271.

[3] See “Preface to the Third Edition,” in Nephi Anderson, Added Upon: A Story, 5th ed. (1898; repr., Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1912).

[4] Nephi Anderson, “To Parents and Teachers,” in A Young Folks’ History of the Church (Salt Lake City: Deseret Sunday School Union, 1919). 4.

[5] Anderson, “To Parents and Teachers.”

[6] Bruce Feiler, “The Stories That Bind Us,” New York Times, 15 March 2013, https://

[7] Robert McKee, Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting (New York: Regan Books, 1997), 13.

[8] Peter Enns, The Bible Tells Me So: Why Defending Scripture Has Made Us Unable to Read It (New York: HarperOne, 2015), 63.

[9] Saints, Volume 2: No Unhallowed Hand, 1846–1893 (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2020), 20–21.

[10] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 331, 440–41.

[11] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 209–10.

[12] Eliza R. Snow, “Sketch of My Life,” 13 April 1885, pp. [1], [36]–[37] (excerpt), document 3.5 in The First Fifty Years of Relief Society, https://

[13] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 341–44, 378–80, 450–52, 481–84.

[14] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand 123–25, 129–32, 134–39, 166–69, 177–79, 186–88, 292–95, 307–10, 484, 518–21.

[15] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 607.

[16] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 331–32, 385–86, 392–93, 427, 445–48, 516–18, 530–32, 558–61, 582–83, 663–66.

[17] Susa Young Gates to Zina D. H. Young, 5 May 1888, MS 7692, box 77, fd 12, Church History Library.

[18] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 164–66.

[19] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 489–91, 499–501, 507–9, 515–16, 528–30; 573–75, 578–80, 591, 612–15, 641–44.

[20] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 138–39, 166–67, 178–79, 187, 326–27, 359, 397–99, 405–7, 448, 450, 471.

[21] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 419–20.

[22] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 137, 166–68, 202–3, 405–6, 516–18.

[23] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 667–69.

[24] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 318–20, 323–28.

[25] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 401–5, 509–11.

[26] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 580–82.

[27] George Q. Cannon, Journal, 9 September 1889, Church Historian’s Press website.

[28] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 543–45.

[29] Saints: No Unhallowed Hand, 479–81, 573–75.

[30] Maria S. Ellsworth, Mormon Odyssey: The Story of Ida Hunt Udall, Plural Wife (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992).

[31] Autobiography of Lorena Eugenia Washburn Larsen (Provo, UT: published by her children, Brigham Young University Press, 1962).

[32] Peter Forbes, “Toward a New Relationship,” PDF file, peterforbes.com, 2007, https://

[33] The phrase is Matthew Arnold’s; see his “Culture and Its Enemies” (1867), in The Spirit of the Age: Victorian Essays, ed. Gertrude Himmelfarb (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 205–24.

[34] For a reflection on faith in the internet age, see Bruce C. Hafen and Marie K. Hafen, Faith Is Not Blind (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018).

[35] Patrick Q. Mason, Planted: Belief and Belonging in an Age of Doubt (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2015), 122.

[36] Richard White, Remembering Ahanagran: Storytelling in a Family’s Past (New York: Hill and Wang, 1998), 35.