Discussing Difficult Topics: The Book of Abraham

Robin Scott Jensen, Kerry Muhlestein, and Scott C. Esplin

Robin S. Jensen, Kerry Muhlestein, and Scott C. Esplin, "Discussing Difficult Topics: The Book of Abraham," Religious Educator 21, no. 3 (2020): 117–39.

Robin S. Jensen (jensenrob@churchofjesuschrist.org) was an associate managing historian of the Joseph Smith Papers housed at the Church History Department when this was published.

Kerry Muhlestein (kerry_muhlestein@byu.edu) was a professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this was published.

Scott C. Esplin (scott_esplin@byu.edu) was a professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU and the publications director of the Religious Studies Center when this was published.

We need to find the unifying aspects of it because if the Book of Abraham is dividing us as Latter-day Saints, then we are failing in reading and believing in it as scripture.

We need to find the unifying aspects of it because if the Book of Abraham is dividing us as Latter-day Saints, then we are failing in reading and believing in it as scripture.

Scott Esplin: I’m interviewing Robin Jensen from the Church History Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and Kerry Muhlestein from the Ancient Scripture Department of Religious Education at Brigham Young University to talk with them about scholarship relative to the Book of Abraham. Thank you for your willingness to help our readers understand scholarship on this topic. The two of you model how to pursue a faithful study of the Book of Abraham from different backgrounds and approaches. Will you introduce yourselves to our readers and share the lens through which you study this text?

Robin Jensen: My name is Robin Jensen, and I’ve worked for the Joseph Smith Papers for over fifteen years. It’s been a tremendous opportunity to dive into Joseph Smith’s papers and his life. I began working as a research assistant for the Joseph Smith Papers when I was a master’s student at BYU. I felt like I was in heaven, and that feeling has never changed. When I graduated from BYU, I took on a full-time job with the Joseph Smith Papers when the project moved from BYU to the Church History Department. Concurrently, I have continued with my education. I have a master’s of library and information science with an archival concentration, and I have recently completed my PhD in American history at the University of Utah. I have served as co-volume editor for each of the volumes in the Revelations and Translation series of the Joseph Smith Papers. This means I’ve studied Joseph Smith’s sacred texts both in manuscript and printed form. I’ve worked with Royal Skousen in publishing the Book of Mormon manuscripts. I’ve even done a little bit of work with the manuscripts of the Joseph Smith–inspired revision of the Bible. I also served as co-volume editor for the fourth volume of the Revelations and Translation series: The Book of Abraham and Other Related Manuscripts, the topic that brings us here together.[1] And so, I come to the Book of Abraham with a background in early Church history and record keeping as well as in Joseph Smith’s practice of bringing forth latter-day scripture.

Esplin: Thank you. Kerry, tell us about your background and approach.

Kerry Muhlestein: I come at this from a two-pronged approach, one prong longer than the other. While I was working on my MA here at BYU in ancient Near Eastern studies, I focused especially on interactions between Egypt and the Israelites. At the same time as I was an undergrad and during my master’s program, I was a research assistant working on the biography of John A. Widtsoe. I ended up going to archives and getting a lot of archival training, not in the same way that Robin did, but still getting that kind of training. So I was kind of dabbling in both twentieth-century AD and twentieth-century BC stuff at the same time. And then I went on to do my PhD at UCLA in Egyptology, during which time I ended up with jobs in history departments at UCLA and Cal Poly Pomona. In taking and teaching history courses, I’ve studied and taught historical method. A big part of my PhD program was also focused on the interactions of the Egyptian and biblical worlds and Egyptian religion and symbolism. So again my studies involved both modern and ancient historical research and methodology. My first job was at BYU–Hawaii, where I was in a joint position in the History Department and the Religious Education Department. Again I had the opportunity to continue to do more modern historical research (for me, nineteenth century is very modern) while also maintaining my research in the ancient world, especially with a focus on Egyptology. The Book of Abraham is that perfect world where all my interests, both biblical, Egyptological, and modern historical worlds combine in a wonderful way.

Esplin: You also are active in the archaeological world in Egypt with BYU’s dig over there.

Muhlestein: Yes. I direct an excavation in Egypt, and I’m really active in doing Egyptological research. I’m always doing something in that discipline.

Esplin: Great, thank you. That will help our readers understand who you are and the approaches we’re going to take in this discussion. So, let’s summarize for the readers the current state of scholarship on the Book of Abraham. What should teachers know and do in their classes as they teach this text? Robin, would you mind starting with that one because you were co-volume editor on some of the most important Book of Abraham materials to have come out recently? Bring our readers up to speed on that volume and other things that are going on in this field of research because you’re right at the heart of it.

Jensen: I’d be happy to, though since I don’t spend any time in the classroom myself, I hope my advice won’t be wildly impractical. I look forward to learning from Kerry’s teaching experience.

Since it was first captured on paper in the nineteenth century, we’ve had people commenting on the veracity of the Book of Abraham. In the early twentieth century, individuals tried to make sense of the Book of Abraham. Reverend Franklin S. Spalding, an Episcopal bishop in Salt Lake City, approached various Egyptologists of his day trying to understand the Book of Abraham. The resulting pamphlet was published in 1912 and was quite critical of Joseph Smith and both the ancient and nineteenth-century origin of the Book of Abraham.[2] In 1967 some of the papyri that were owned by Joseph Smith were acquired by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[3] Following this acquisition, there were many published analyses of the papyri, both Church-sponsored and independent. And we’ve had the wonderful contribution of both members and nonmembers alike, Egyptologists, historians, and nonspecialist researchers. Without the efforts of Klaus Baer, Hugh Nibley, John Gee, and Brian Hauglid, we would not know what we now know. Some might look at that scholarship and say, “Okay, well, in that long history, we must have figured everything out. Or at least we have answered most of the pressing questions.” And I actually look at that scholarship and think to myself, “Boy, we have a long way to go.” There are so many approaches to the Book of Abraham, so we really do need to be more systematic and invite many more scholars to the table so that we can learn from the best.

In saying all of that, I think there are two main issues at play when looking at the Book of Abraham. First, different scholars bring differing expertise and approaches to the topic. Second, how we got the Book of Abraham is a big hurdle for many. Book of Abraham scholarship is, in some ways, very difficult to summarize. You would get different answers from every Book of Abraham scholar you would ask. Egyptologists look at the Book of Abraham from one perspective, and American historians look at it from another perspective.

But I think in particular with the Book of Abraham, issues of truth claims can affect scholarship a great deal. If we were to look at a spectrum, so to speak, I think that we have some scholars who do not believe Joseph Smith’s story of the coming forth of the Book of Abraham. So they develop theories to explain the Book of Abraham from a more humanistic approach. That’s probably one extreme. The other end of the spectrum is to acknowledge Joseph Smith’s divine mission and to try to fit all the evidence into a miraculous event. In other words, they lay all the archival records and all the questions we might have at the feet of divine intervention or divine inspiration through Joseph Smith. If those are the two extremes, you can imagine that there’s a lot of middle ground—allowing for spiritual experiences and human foibles or agency.

So, teachers in the classroom might stumble in interpreting the unanswered questions and in navigating the spectrum of scholarship. Obviously, seminary and institute teachers will need to allow for God to be in the process, but I believe it is also important to maintain that Joseph and those around him were still acting as agents for themselves. Other teachers might consider teaching the Book of Abraham with no single “theory” as a conclusion to the lesson. And of course, the Gospel Topics essay on the Church’s website about the translation and historicity of the Book of Abraham is a tremendous resource for Church Educational personnel.[4]

Esplin: If I can interject before Kerry comments, what does the Joseph Smith Papers volume on the Book of Abraham bring to the table?

Jensen: The fundamental goal of the Joseph Smith Papers is to present historical documents in an easily accessible format to be used by other scholars in their own research. Our volumes are reference works, meant to replace the need for scholars to come to the Church History Library and look at these documents.

Muhlestein: And may I add that the notes and the annotations in the volumes add incredible value to the core documents. It makes it possible not just to look at the documents themselves, but to see the background homework someone has already done—you don’t have to do it yourself in order to understand some of what’s going on with the documents. Of course, those valuable aids are also the place where interpretation can creep in.

Jensen: Yes, documentary editing really has several goals, one of which is to present the text, but another is to present the context of that document. So, you can have a document in front of you, and you might have a lot of questions such as “Wait, this mentions a John Doe. Who’s John Doe?” or, “Hey, what’s the significance of this date?” or, “What prompts their creation of this record?” We in the documentary editing field try to answer as many of those questions as possible while also acknowledging that we can’t answer every question. History is finding and assembling puzzle pieces to make a picture while recognizing that most of the pieces are missing. So, this volume of the Joseph Smith Papers is meant to offer scholars resources to use in their own attempts at making sense of the past. In saying that, I will be the first to admit that some scholars are never satisfied with any sort of reproduction. But I would venture to guess that scholars will be able to get answers to 95 percent of the questions they might have through the scans and transcripts that we have presented in this book.

Esplin: Kerry, especially with your background in teaching, what would you add? Will you bring our readers up to speed on Book of Abraham scholarship from a teacher’s perspective?

Muhlestein: Well, there are indeed a lot of disciplines behind Book of Abraham scholarship. It’s a complex text that has a lot of different avenues of research. As we’ve said, one of the important avenues is the nineteenth-century history of the book. Revelations, volume 4, does a fantastic job of making some of that available. I will give personal testimony about the volume’s value when it comes to questions that I’ve researched regarding Joseph Smith’s work with the translation of the Book of Abraham. Until this print volume came out, I was unable to do some of the research I wanted to, even having sometimes seen the original documents and having access to them online. So, it’s an incredibly valuable tool in that way. I think you can tell when a research tool like this volume has been done well, because it will enable researchers to see that it has its own limitations. I think that’s the problem of the historian or any scholar. You know you’re providing the foundation for someone else to come and understand things better and recognize the mistakes that you made. Often, that scholar is yourself. You’ll look at something you wrote five years ago and say, “Oh, I have a lot of wrong things in there.” So, this is an incredibly valuable tool that has already helped me understand various things better, and at the same time, it reveals some of its own limitations.

Besides the nineteenth-century context, there are also two ancient contexts for the Book of Abraham. One is the era of Abraham’s life. We’re talking about roughly 2000 BC. If we want to understand what’s going on in the story that’s in the text of the Book of Abraham—rather than the story of the coming forth of the Book of Abraham—we want to look at that ancient context. I would say in the last twenty years, we’ve had twenty times as much research done on the Book of Abraham as in the hundred years before that. So, we have some great work coming out in that avenue of research. Some of this has been happening in what was FARMS—now the Maxwell Institute.[5] Some research is also coming out in Religious Studies Center publications.[6] There’s a great new website called pearlofgreatpricecentral.org that I think has some really good information. The Interpreter Foundation has some wonderful material as well.[7]

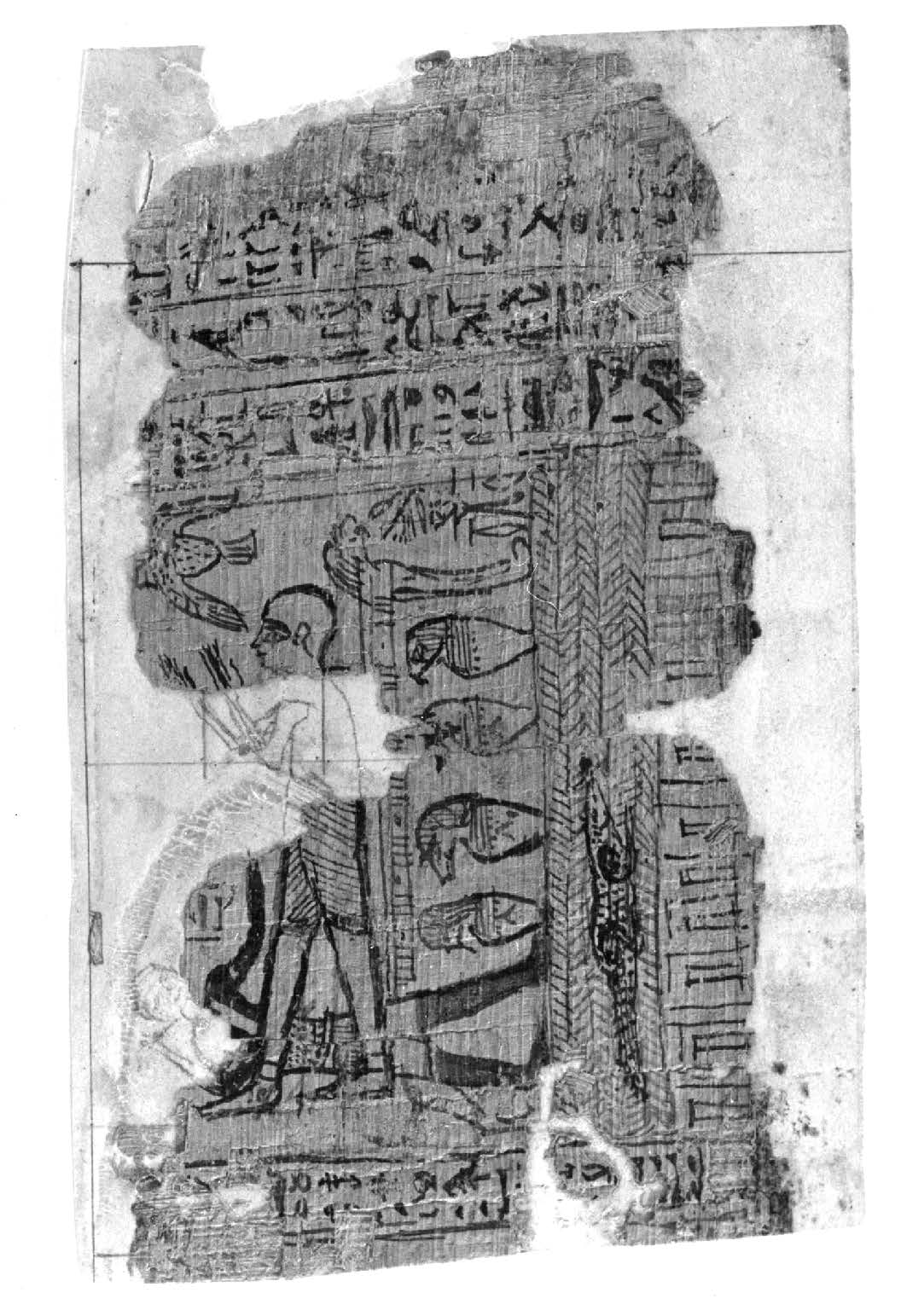

The second ancient context—which has traditionally received less attention but is now being examined more carefully—is the context of the papyri that Joseph Smith owned. That historical context is still in Egypt, but about 200 BC, so quite a bit later than Abraham’s day. This is likely the period when the papyri that Joseph Smith owned were created, so trying to understand that historical context is also important.[8]

Esplin: That takes us to a related topic. Help our readers understand the origins of the Book of Abraham.

Muhlestein: I think this is one of the most fascinating of all the stories of how we got a book of scripture, partially because there’s so much we don’t know. I don’t know if Abraham wrote the text himself or if he used a scribe, but at some point he wrote or dictated a text in ancient times. And then we know nothing about how it was preserved from Abraham’s day to 200 BC. We can make speculations. Did it stay in Egypt after Abraham left? Or did it come with Jacob when he migrated to Egypt? Was it brought back when huge groups of Jews moved into Egypt in Jeremiah’s day and afterwards? There were large numbers of Jews in Egypt by 200 BC, any of whom could have possessed a copy of the Book of Abraham. We don’t know the details, but somehow that text came into Egypt. At that point it has to be a copy of a copy of a copy of the original, which is how ancient documents were transmitted. All of our scriptural texts are translations of a copy of a copy of a copy. We don’t have any original, or what we call “autograph,” copies of a scriptural book. We do not have the one that Isaiah wrote or that Jeremiah dictated to his scribe. We don’t have the autograph for any of those.

Jensen: Or even more recently with the New Testament.

Muhlestein: Right.

Jensen: Nothing in the Bible is an original manuscript.

Muhlestein: Yes. I’ll amend my earlier statement. I wouldn’t say we don’t have any autograph texts for any scripture. We do for the Doctrine and Covenants, which Robin has edited. That’s the scriptural book for which we have autograph copies. Even for the Book of Mormon, we don’t have the plates anymore.

Jensen: And even with the revelations of the Doctrine and Covenants, there are very, very few original, dictated versions. Most of the surviving manuscripts are later copies.

Esplin: Good comparisons. So, help our readers understand why we look to 200 BC for the creation of the papyri. What about the papyri themselves suggests a dating of 200 BC?

Muhlestein: At some point, these texts are copied down in roughly 200 BC. The reason we know that is because the original drawing of Facsimile 1 was on a papyrus fragment owned by a priest whom we can identify. We can identify his father and grandfather and son and grandson and great-grandson. So, we can provide a pretty good date for the life of the priest.[9] He lived about 200 BC. He may be the owner of the papyri that the Book of Abraham text was on—we don’t know that for sure, but he at least owned the drawing that is published in the Book of Abraham. That gives us a round date. It’s somewhere around 200 BC that the copies Joseph Smith will end up with were written on papyrus.

Esplin: That’s because he signed the papyrus or just that his name appears on the papyrus?

Muhlestein: That’s exactly right. His name and his father’s name and his priestly titles appear on the papyrus. We can identify that priestly family and document it fairly well. At some point, these papyri end up being preserved because they were buried with some Egyptian mummies. And then in the early nineteenth century, we have a group of people who were collecting antiquities and sending them mostly to European institutions; however, a small collection got sent to the United States. That is the collection that eventually ended up in Kirtland with four mummies and two papyrus rolls and some fragments of papyri that Joseph Smith purchased, and it’s in connection with those papyri that he translated the Book of Abraham.

Esplin: What would you add, Robin?

Jensen: My contribution to the ancient context of the papyri is very small. And in fact, this discussion is part of the larger point that I hope we can make: the scholarship that we’ve done on the Joseph Smith Papers and that other nineteenth-century historians have been able to do on the Book of Abraham really is dependent upon the wonderful work of Hugh Nibley, Kerry, John Gee, and others who have taken a hard look at both of these ancient contexts that Kerry talks about. Kerry mentioned how much scholarship has been done in the last twenty years. I think it’s phenomenal to watch the kind of hand-in-hand contribution of scholarship on the ancient world that I know nothing about. I don’t pretend to, and I am reliant upon the scholarship of others. That is how scholarship works. No one person can know everything about a topic.

When we look at the Book of Abraham, I can maybe egotistically say, “Oh I don’t need anyone else. I’m just going to figure it out all on my own.” And that simply does not work. I guarantee you’re going to fall flat on your face. Kerry talked about standing on the shoulders of past scholarship. I wholeheartedly agree. We sometimes diminish or belittle past scholarship because we know so much more now, but we need to really maintain our humility. I’d love to see even more collaboration by bringing together expertise from various individuals. Ultimately, the Book of Abraham really is an amazing book of scripture. And like all scripture, this book can stand up to scholarly scrutiny. Our views on that book might be different after our study, but it will still be scripture for millions of members worldwide and part of the jointly shared, rich heritage that I hope we all can appreciate.

Esplin: Related to that, Robin, Kerry spoke about the two origins or the two ancient contexts of the Book of Abraham, or the papyri. What can you tell us about the nineteenth-century context of those papyri? That’s a piece where you could really enlighten us as well.

Jensen: And it’s an important piece too. I think that in order to understand Joseph Smith’s excitement about the papyri, we need to situate him in his nineteenth-century setting. I really don’t think that we truly understand the kind of mass excitement people from the nineteenth century felt over these Egyptian antiquities. Some scholars call this period the Egyptomania of the nineteenth century. Joseph is very interested in the ancient world. Where better to find fragments of that past than through all the mummies and papyri that are surfacing? And then there’s this really important intellectual context concerning the hieroglyphs that Joseph Smith has inherited. Many scholars before and during Joseph Smith’s lifetime are trying to make sense of the hieroglyphs. We even had scholars hundreds of years before Champollion actually deciphered the hieroglyphs in the early nineteenth century who claimed to have translated Egyptian writing. Joseph Smith is part of a culture that says, “You know, through study and effort we might be able to read this ancient language.” A final aspect of Joseph’s context that is crucial to understand is his past production of scripture. He was an ardent believer that God spoke to his children throughout all of earth’s history. And when God spoke to his children, those children wrote down his messages. God revealed in the Bible revision project that Adam and Eve wrote things down and taught language to their children. Joseph attempts to recover the Adamic language, and he’s interested in recovering truths found in ancient cultures. The Book of Mormon, after all, is an entire civilization’s history. With all three of those backdrops, to me, it is so easy to see that when ancient papyri come into Kirtland, Joseph is going to be interested in them intellectually and as something that can teach him about God and his revelations to his children.

Esplin: You mentioned the universality of this interest. I enjoy asking my students on campus when I’m teaching Doctrine and Covenants, Church history, Book of Abraham, or whatever, how many have seen Egyptian artifacts outside of Egypt? There are always dozens in my classes who will have seen artifacts across the United States, Europe, or in other places. There is a fascination with this culture still today.

Muhlestein: To understand that context a little more, people need to realize that that opportunity didn’t exist before Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt, which occurred in 1798. These papyri were part of the first large collection of Egyptian antiquities that came to America. Joseph Smith purchased some of the first Egyptian antiquities to come to the United States. That’s part of why it caught the imagination of Americans so much, because it was so new. The mystery and excitement was a wave that swept across both Europe and America.[10]

Esplin: And I think it still persists today. There’s still a fascination with ancient Egypt.

Muhlestein: Yes. But it’s not quite as new, so it’s not quite the fervor now as it was then, I would say.

Esplin: That gets us to the next question, then. You’ve led into it well. So, the papyri are in Joseph Smith’s hands in Kirtland. What do we know about the translation process? Is it important to have a testimony of both the process and the product? If so, why?

Jensen: This is an important question. Historians as far back as Leopold Ranke started creating a hierarchy of sources. How do you trust sources? How do you trust the archives that hold those sources? Is one source inferior to another source? And I would say that when you look at the translation of Joseph Smith, from one perspective we actually know quite a bit about it. Joseph Smith and several of his clerks—Warren Parrish, Frederick G. Williams, William W. Phelps, and Oliver Cowdery—began work in the middle of 1835 to capture the Book of Abraham in writing. It was eventually published in 1842 in the Church-owned newspaper the Times and Seasons. We have many of the original manuscripts they used, and we even have diaries and letters that give a hint of the initial reaction from members about the new scripture. But from a different perspective, we don’t know nearly enough. I have so many questions about the simple mechanics of how the translation actually happened. Joseph did not often get into details in describing the intricacies of his translation efforts. Joseph would often simply say that he translated the Book of Mormon “by the gift and power of God.” In some ways, that is the perfect answer. It is through God that he produced the Book of Mormon. But for me as a historian, it’s not going to satisfy my curiosity of how it actually happened.

With the Book of Abraham, we actually have even less than that from Joseph. We don’t have any firsthand accounts from Joseph describing the context, the process—anything. Therefore, we’re left to rely upon secondary witnesses. And there’s actually very few of those as well. Wilford Woodruff was in the Nauvoo printing office, and he documented a few things in his diary.[11] Parley P. Pratt was in England when the Book of Abraham was published, and he made some comments about the translation process, though we don’t know how he gained the knowledge he had of the translation.[12] And Warren Parrish, who was a scribe in Kirtland, left a brief account. So, yes. The question about translation is a frustrating one, particularly for those who have an infinite curiosity. But before I answer the second question, Kerry, I don’t know if you have anything to add.

Muhlestein: Parrish’s statement is somewhat similar to what Joseph Smith said about the Book of Mormon, where he says, “I set by his side . . . as he claimed to receive it by inspiration from Heaven.”[13] That’s essentially all we know, just like with the Book of Mormon: somehow this came from God. And to be honest, I wonder sometimes if part of the reason Joseph Smith doesn’t tell us more is because while he is intimately familiar with the translation process, he may not fully understand it himself. He’s a tool God is using. And I’m not sure he understands the mechanics of the flow of revelation that he’s receiving. Probably his best description of what’s happening to him is that he is able to translate by “the gift and power of God.” That much he knows.

Jensen: I think we could ask the readers this. Think back to your most powerful spiritual experience. Remember what it felt like. What did it teach you? Now answer the question, How did that happen? And you’re at a loss for words, right? You just don’t know how to put that into words. You know, I look back on my own life and some of the powerful spiritual experiences that I’ve had. I’ve told them in many different ways because I’ve never felt satisfied in how I’ve been able to express the way it’s impacted my life or how it’s worked through me. Kerry’s absolutely right. I think Joseph is the same way. He knows that there’s a greater power than himself that’s channeling through him to create something, but if he tries to explain the process, then he’s probably going to be dissatisfied with his explanation.

Muhlestein: I think that’s well said. Joseph talks about the text that’s on the papyri, so it’s clear that the translation is associated with the papyri, but it’s not clear if this is like the Book of Mormon in that he had a text on the papyrus in one language that he was translating into English. Or is it more like his translation of the Bible where he had a text on the papyri, but he was giving us things that weren’t even on those papyri. Or maybe it’s a combination, a translation of text that is on the papyri and also of text that is not on the papyri. We really don’t know what the translation mechanism is. Which leads us to that second part of your question, which was?

Esplin: Is it important to have a testimony of both the process and the product? If so, why?

Muhlestein: I think it’s important to have a testimony of both, but more limited in regard to the process. I would put it this way: I change my mind from time to time as to my opinion about how much of the Book of Abraham was on the papyri, if any at all. I really don’t know. And I don’t think I need to have a testimony of whether Joseph was using the Urim and Thummim, or whether the text was on the papyrus; but I do have a testimony of the part that we’ve mentioned, which is that “it comes from God.” I think we need to have a testimony of the fact that that process, whatever it looked like, was divinely inspired, and that there was an ancient text somewhere. Beyond that, I don’t think we can answer the questions about the process well enough for someone to have a testimony about it. As for the product, absolutely we need to have a testimony of that because that’s divine scripture canonized by the Church, and we are welcome to have revelation from the Holy Ghost to tell us that it’s divine scripture.

Jensen: Let’s take a very minor example. Maybe this is a terrible metaphor, but as I’m reading from a printed copy of the Book of Mormon, I’m never thinking about how the actual artifact in my hand was produced. I don’t think about the print center. I don’t think about the many hands (or machines) that made it happen. I don’t think about the compositors or computers that set the type. I don’t think about the proofers or folding machines. I don’t think about any of that because that’s not what I do to approach the scriptures. And that could be seen as a comparison to the Book of Abraham. When I’m reading the Book of Abraham in a devotional setting, I’m not usually thinking of 1835, Kirtland, or William W. Phelps. I’m wondering how this book of scripture affects me. Does the text itself lead me to God? Is the Spirit working with me to help me understand that this is truth? Because that’s the scripture’s purpose: to bring us to God, to bring us to a better understanding of Jesus.

But in saying this, I don’t mean to imply that we should ignore the nineteenth-century origins of the English text of the Book of Abraham. I see the wrestle of trying to understand the origin of the Book of Abraham as, in some ways, deeply spiritual to me. I believe that God will see my effort of making sense of the historical background of the Book of Abraham and reward me with insight into that book of scripture. I think that scriptures are absolutely comforting there, absolutely a source of spiritual truth. But I think scriptures can and also should be challenging. And I think that wrestle shows God that we are serious about this text. When God sees us being serious about something—that we’re struggling and maybe begging for insight—then I think that’s when the Spirit can come in and say, “Okay, let me tell you some truth about this.” And it might not actually be part of the text, it might not be part of the nineteenth-century history, but I’ve felt universal truth through studying the origin of the Book of Abraham.

Esplin: By focusing too much on one approach over another, I might miss those truths.

Jensen: The nineteenth-century origin of the English text of the Book of Abraham is an academic investigation. And while I’ve felt the Spirit in my own academic investigations, I also realize that I need to be humble in recognizing where the academy fails us so often, because scholarly truth is wildly different than spiritual truth. So while I find spiritual truth in uncovering and better understanding the nineteenth-century origin, there is also the academic truth that has to change every time new data arises or a scholar challenges my assumptions.

Esplin: Thank you for that discussion of the translation process. Let’s get into some of the more technical matters of that translation process, especially as the fourth Joseph Smith Papers volume has brought these to our understanding. Will you summarize for our readers the various documents related to the Book of Abraham that are published in that Joseph Smith Papers volume, as well as what role these Kirtland Egyptian papers and other documents have in the coming forth of the Book of Abraham?

Jensen: For the Joseph Smith Papers, we include records falling into two criteria—authored or owned by Joseph Smith. By following those criteria, we’ve published in the Joseph Smith Papers volumes a number of documents that relate to the coming forth of the Book of Abraham. The first we’ve already talked about—the papyri that were owned by Joseph Smith. Though these documents are thousands of years old, we felt that they should be included in this volume because he owned them. Since we wanted this volume to be centered on Joseph Smith, we did not give much by way of ancient context for those documents. So we presented high-quality photographs of them without any translation of the actual papyri, realizing that Egyptologists have and will continue to offer better translations of them than we could. The second grouping of documents are what I call the Egyptian language documents, but which other scholars have called the Kirtland Egyptian Papers. These records contain copies of ancient characters, alphabets and grammars, and other miscellaneous records that show, to me, Joseph and his scribes attempting to understand the papyri. These documents are unfamiliar to most Latter-day Saints. The third collection of documents are texts that would be very familiar to members of the Church: manuscript and printed versions of the Book of Abraham.

Muhlestein: Maybe I can just add that one of the most valuable things Robin and the JSP editors made available in Revelations, vol. 4, is a collection of lists of the signs that are in the papyri, that are in the Egyptian language documents, and what Joseph Smith or Oliver Cowdery or W. W. Phelps said they meant. The editors collated them and assigned them all numbers so that now we can talk about them in a scholarly discourse. In some ways, that brings us back to the discussion we were having earlier about how this is a tool that allows for better research to be done.

For example, if we’re going to ask about the translation process, one of the questions people have often asked is, What is the relationship between those Egyptian language documents, most of which seem not to have been owned by Joseph Smith, and the translation process? Are the language documents tools that Joseph Smith used to create the Book of Abraham or not? You’ll find believing scholars have different points of view on that issue. Some have proposed that the grammar and alphabet documents were used to translate the characters that were in the margin of the translation manuscripts.

This can illustrate a couple of different ways that this volume helps us approach that question. Some have proposed that the language documents were used to translate the Egyptian characters in the margin of the translation documents. Because of the way that all these characters and documents are collated in Revelations, vol. 4, I was able to look at that question and determine there’s a 98 percent chance the Grammar and Alphabet volume was not used to translate those particular characters. Really, we can provide that kind of a percentage number. That doesn’t mean it wasn’t used at all, but we now know that one way some have proposed it was used doesn’t work.

There is another aspect worth discussing. I think this is one of the places that Robin and I differ a little bit, which is great that we can both believe in the Book of Abraham and differ in approaches. It seems to me that the apparatus in Revelations, vol. 4—the footnotes and so on—were suggesting that at least in some way, the alphabets and the grammar were used to create the text of the Book of Abraham or were the tool of translation. Maybe I’m misreading that, but it seems to me that this interpretation is implied throughout the notes. As I looked more carefully at the footnotes, I realized partially why some people would see it that way, an understanding I hadn’t seen before. This caused me to look at the historical sources more carefully, questioning my earlier conclusions. I am working on researching this still, but now I think we can create a timeline that argues against that notion. That’s something I couldn’t have done without building on the scholarship that had already been presented in the volume. Thus Revelations, vol. 4, is a tool that creates the opportunity to demonstrate how to improve and update itself.

I think that we will have a scholarly dialogue for a long time on the relationship between the Egyptian language documents and the translation, but that dialogue can only take place because we build on each other’s scholarship and recognize that while I do think that there are some positions that don’t come from a faithful point of view, there are also multiple positions that do come from a faithful point of view, and that scholarly dialogue can get us inching closer and closer to a better understanding of what really is going on. I think that some would disagree as to what positions truly foster faith and which don’t, but hopefully careful thinking and scholarship combined with genuine and open dialogue can continue to move us towards a greater agreement.

Jensen: I think, Kerry, that what you said there is really important because you’ve spent a long time researching the Book of Abraham—twenty plus years now that you’ve been working on this?

Muhlestein: Yes, probably about twenty years.

Jensen: I have not been spending that much time, but it’s probably been about ten years for me now. Those engaged in the academy recognize that scholarship involves kind of a confrontation at times. Assessing another’s positions involves some critical thinking (critical in the sense of weighing all the sources), where you look at someone’s argument and say, “You know what, that doesn’t work for me for the following reasons.” And then you publish those arguments, and then another scholar comes along and says, “Actually, you’re wrong in these points, let me give you an alternative.” That goes back and forth, and what a lot of people get fixated on is being critical of one another (critical in the sense of attacking someone). However, if you step back, you can actually see scholarship moving incrementally forward. I’ve really admired Kerry’s engagement in a lot of these issues because in all of our interactions, I’ve felt nothing but admiration and respect for Kerry. He is one that wants to find the scholarly truth about a matter. And even if we disagree on certain points, I’ve never felt that he has belittled me or somehow said, “I can’t believe you actually think that.” I think that particularly within Book of Abraham scholarship, where we are all trying to look to the coming forth of scripture, it’s sometimes hard to—well, it shouldn’t be hard—but it sometimes is hard to remember that we’re all trying to build a Zion community. At the end of the day we are fellow Latter-day Saints or we’re fellow travelers in the discovery of not only academic truth, but also spiritual truth for believers. We can disagree, but ultimately, we can say, “You know what? We do share a love of, a belief in, or a respect for the Book of Abraham and what it means to believing members.”

Esplin: I think that gets to an important point. It appears that the controversy involving the Book of Abraham seems to be more about the context of its coming forth than it generally is about its theological content. Would that be accurate?

Jensen: Generally speaking, I would think so. As Kerry mentioned, there are a lot of different debates, but I think one major debate that Kerry mentioned is the relationship between these Egyptian language documents and the Book of Abraham documents. In the Joseph Smith Papers volume, we’ve tried to be fairly neutral. It’s impossible to be neutral in all senses in scholarship, but we have a number of footnotes and other introductions where we flat out say, “The relationship between the two sets of documents is unknown.” We try to leave it open for scholars to come along and add their own research or reasoning.

Esplin: As scholars who have spent significant time studying this issue, what are your thoughts about the translation process?

Jensen: If we’re talking about my own personal belief—as I look at the documents, my opinions indeed differ from what Kerry thinks. If I had to give my best assessment, I would generally describe it like this: Joseph Smith tries to make sense of the papyri by instructing his clerks to make copies of the papyri, and then he produces these Egyptian language documents with the assistance of his clerks. As part of that intellectual study—perhaps during or after—he then also dictates the Book of Abraham to his clerks. I don’t see anything doctrinally inaccurate about that process. In other words, we have an example along similar lines during the Book of Mormon translation. Oliver Cowdery wanted to translate; he received revelation saying he could, yet he wasn’t able to. Joseph receives a revelation explaining why he couldn’t, and God essentially says, “You just thought I’d give it to you. You need to realize that you have to study this out in your mind” (see Doctrine and Covenants 9:7–8). To say that Joseph gets the papyri, studies it out, produces some Egyptian language documents, and then receives the Book of Abraham through inspiration does not seem doctrinally unsound. To me it is not threatening to say that Joseph is kind of groping along trying to make sense of the writings on the papyri through that intellectual process and then he receives this incredible revelation, this translation of the Book of Abraham.

Muhlestein: To piggyback off of what Robin was saying a moment ago, this is what I think is valuable. We can disagree on that particular point. At the same time, on other issues we’ll agree. I think at least in Robin’s and my relationship, in certain discussions between us, we’ve been able to say, “I fear that if someone takes this point of view, that if you follow it through to the end, it might be faith diminishing.” And we can have that discussion without it being accusatory. Sometimes you move closer to each other’s point of view, and sometimes you don’t, but at least our thoughts have been clarified, and we can move forward and build on each other’s scholarship. So I think that’s an important aspect to consider as we think about what has been controversial. Yes, certainly the nineteenth-century coming forth of the Book of Abraham has been the most controversial. But let’s not forget that some people have had questions about the ancient context of the Book of Abraham. That is probably a topic for another conversation. For now I would refer people to pearlofgreatpricecentral.org, and then let’s return to the topic at hand. I would say that right now, much of our greatest research focus is on the nineteenth-century context and the documents that are contained in Revelations, vol. 4.

Esplin: Sometimes people, scholars, or students of the Book of Abraham perceive that there is a faithful approach and a scholarly approach to this text. Do you think that divide is accurate? And does there need to be a divide? What is the relationship between faith and scholarship in studying the Book of Abraham?

Muhlestein: I would say that we want to worship the Lord with our mind and our heart. I don’t see this as a divide. Elder Maxwell frequently spoke about the need to be a disciple-scholar who is consecrated, and I think that’s his way of saying that there shouldn’t be a division here. At the same time, I think we should recognize that we’re beings made of an intellect and a spirit, and as we use them both, hopefully they unite; but what I learn spiritually, I believe, should influence how I see things intellectually and vice versa. They should interact with each other. The mind should not be used exclusively, and neither should our heart. We must approach this by study and by faith.[14]

Jensen: It’s interesting that in this conversation we’ve just had, we’ve both been trying to understand the historical and the spiritual truth—though we might come at that from different backgrounds, or we might even come to different conclusions. And in no way have I seen that as a divide. We’re copartners in trying to figure that out. And then when there has been a difference of opinion, when we have disagreed, I hadn’t necessarily seen it as a “well, it’s either your way or my way”—it’s more of a “oh, that’s a really interesting point. Let’s explore what that means from my perspective. Let’s explore the implication.” In other words, we’re still trying to find that understanding with each other. And I hope that is something Book of Abraham scholarship can improve upon. Is there currently a divide? Yes, sometimes I see a divide. Sometimes people in shorthand say, “Oh, you’re aligning with critics of the Church, therefore I won’t listen to what you have to say.” Or, “Oh, you’re aligning with apologists, you must not be scholarly.” Or, “How could you be a faithful member if you believe in this theory?” Such rhetoric or thinking has done damage to the scholarly discussions surrounding the Book of Abraham. I hope we can move past that because I completely second Kerry’s thoughts that in my own life, there’s absolutely not a divide between a scholarly and a faithful approach. In fact, I would not know what to do with myself if I removed the scholarly inquiry from my brain. I mean, that’s part of who I am. But at the same time, I have to have that truth, the Spirit, the divine spark inside of me because that’s also what makes me who I am. There are sometimes things you discover in academic research that lead you to think, “That’s not how I envisioned it, and maybe I have to recalibrate my testimony and figure out where this faith is actually coming from.” It’s a lifelong journey for sure, but this is, I believe, what we’re called to do. We are called to be faithful scholars that—not to ignore scholarship, not to ignore historical data that’s in front of us—use that scholarship as a way of building up Zion.

Muhlestein: Maybe I can just add two things to that. I would say that for myself, as I think about my greatest spiritual insights, they have come when I’ve been applying my mind in deep, scholarly, intellectual pursuits of the scriptures. In other words, I have these kinds of spiritual insights when I throw my whole mind, and at the same time, my whole heart, into understanding the scriptures. I agree with Robin when he says that we don’t always have to agree, that we can say, “Okay, that’s your point of view, this is my point of view, and its fine that we differ.” The more we can do that, the better. At the same time, I do think it’s important to say, “Let’s think through some of the ramifications of a certain position.” Sometimes, if you think one view through to its end, it actually can be faith-diminishing. Both faith and the evidence at hand need to be taken into account. I don’t mean to imply in all of this, and I don’t think that Robin means to imply, that all positions are okay doctrinally. Some theories may seem doctrinally safe until we think them through more carefully. I’ll just use one specific example. Some say, “Well, this may be an inspired revelation that comes to Joseph Smith that teaches us things, but it’s not actually connected with Abraham the person—it wasn’t an actual historical text.” In my opinion, if you follow that theory through to where it can lead you, when you stop accepting the historicity of the Book of Abraham, it is likely that eventually you will start accepting a number of other ideas that will begin to undermine your faith. So, I think there are some positions that can undermine faith, and we should be mindful of that; while at the same time, there are many differing positions that don’t undermine faith. And being able to distinguish between those is an important and necessary thing to do. Evidence, theories, and faith all interact, and we should be careful and mindful of how they interact and how to prioritize them.

Esplin: How has your in-depth study of the Book of Abraham impacted your faith and your testimony? As we conclude, you’ve spent as much time as anyone in the Church studying this book of scripture. What has it done for your faith and testimony?

Jensen: The Book of Abraham is a complicated text, and it should be. I keep going back to this thought that scripture should be challenging to us. I think about what it would have been like to go back and live in the time of Christ and to really hear his introduction of a Christian life. The New Testament is full of truly radical teachings. To really follow Christ’s teachings is nigh impossible. Giving up family, giving up friends, giving up your life for the Lord’s sake, that is a very difficult, challenging thing to do. And I believe that that is what the gospel calls us to do: to challenge us, to challenge our faith, to challenge our way of living. So, I don’t see a problem in viewing the Book of Abraham as challenging, complicated, difficult—because that’s ultimately what I see all scripture to be.

Another thought that occurs to me is that there is a difference between sacred text and scripture. Sacred text is something that a prophet reveals. Scripture is something that a community believes in. And maybe that’s just a differentiation in my own mind, but the Book of Abraham is both scripture and a sacred text. We can look at how Joseph Smith translated this sacred text and try to envision how it came to be—through inspiration or God’s channeling. But then, when I remember that it’s also scripture, I remember that Joseph had a whole faith community around him that believed in this work. And this scripture can bring us together. It brings me up to the scholarly table with Kerry to try to make sense of it. It brings me into the pews with fellow members of the Church to teach me about building up Zion. How does this book of scripture make me a better human being? That’s going to be with me for the rest of my life. I need to read this for the rest of my life because it’s a lifelong journey. The Book of Abraham is true. Capital T true spiritually, but also lowercase t true historically. It has a place in history. It’s important to investigate that history. We need to study everything we can about its ancient context, its nineteenth-century translation, and its modern impact because that’s going to give us greater insight into it. But we also need to throw all of our intellectual weight at it. We need to wrestle with it. We need to make sense of it. And we need to find the unifying aspects of this sacred text because if the Book of Abraham is dividing us as Latter-day Saints, then we as a community are failing in reading and believing in it as scripture that should be leading us to Christ. But I’m too much of an optimist. I believe in God too much to think that that’s going to happen. The Book of Abraham will bring us together. It will continue to reveal insights to Church members, and the power of the scripture will, I believe, unite us as Latter-day Saints and teach us to find the way back to God.

Muhlestein: Thanks, Robin. I agree with all of that! For myself, I would say, we can’t focus too exclusively on just one avenue of study. It is when I’m looking at both ancient contexts, the modern context, and the scriptural text itself that I have powerful spiritual insights that affect who I am and that affect my understanding of God, what he would have me do, and my relationship with him. I cannot tell you how many times I’ve had a question—a scriptural question, or a question about my discipline, or a question about these contexts—and as I try to look at all of these things together, they’ve all informed each other so that I suddenly understand an issue. Numerous times I have understood both an Egyptological issue and a scriptural issue better because the two worlds inform each other. These are all different avenues of pursuing truth. I have experienced several times when the Lord has directed us to look in this place, and suddenly we found something that helped us understand the subject better. I have seen that too many times to have any doubts as to whether or not God is intimately involved in this work. God cares about each of us individually and about our interaction with him through his scriptural text. I know that about all scriptural texts, and I know that specifically about the Book of Abraham because it’s happened to me again, and again, and again. Thus, in the end, probably the greatest impact it’s had in my life is that I am more personally connected with God because he has personally interacted with me in regard to these texts. And that has deeply strengthened my testimony of him as my Father.

Esplin: Thank you both for sharing your time, your perspectives, and your faith.

Notes

[1] Robin Scott Jensen and Brian M. Hauglid, eds., Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts, Facsimile edition, vol. 4 of the Revelations and Translations series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, Matthew C. Godfrey, and R. Eric Smith (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2018); hereafter JSP, R4.

[2] For a recent discussion of this episode, see Terryl Givens with Brian M. Hauglid, The Pearl of Greatest Price: Mormonism’s Most Controversial Scripture (New York City: Oxford University Press, 2019), 143–46.

[3] JSP, R4:29.

[4] “Translation and Historicity of the of the Book of Abraham,” Gospel Topics Essays, https://

[5] For example, John Gee and Brian M. Hauglid, eds., Astronomy, Papyrus, and Covenant, Studies in the Book of Abraham, vol. 3 (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2005).

[6] For example, John Gee, An Introduction to the Book of Abraham (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017).

[7] For example, Kerry Muhlestein, “Assessing the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Introduction to the Historiography of their Acquisitions, Translations, and Interpretations,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 22 (2016): 17–49.

[8] See Kerry Muhlestein, “The Religious and Cultural Background of Joseph Smith Papyrus I,” Journal of Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 1 (2013): 20–33.

[9] [9] John Gee, “History of a Theban Priesthood,” in Proceedings of “Et maintenant ce ne sont plus que des villages . . .” Thèbesetsarégion aux époques hellénistique, romaine et Byzantine (Brussels: Association Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, 2008), 59–71.

[10] Kerry Muhlestein, “Prelude to the Pearl: Sweeping Events Leading to the Discovery of the Joseph Smith Papyri,” in Prelude to the Restoration: from Apostasy to the Restored Church (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2004), 130–41.

[11] Woodruff documented in his journal in February 1842 that Smith translated the Book of Abraham “through the Urim & Thummim.” Woodruff, Journal, 19 February 1842, Church History Library.

[12] Pratt stated that the Book of Abraham was “in course of translation by the means of the Urim and Thummim,” in editorial, LDS Millennial Star, July 1842, 3:47.

[13] Warren Parrish, Kirtland, OH, 5 February 1832, Letter to the Editor, Painesville (OH) Republican, 15 Feb. 1838, [3].

[14] Kerry Muhlestein, “The Book of Abraham, Revelation, and You,” Ensign, December 2018, 54–57.