Nephi and Effective Followership

Christopher J. Peterson

Christopher James Peterson, "Nephi and Effective Followership," Religious Educator 21, no. 2 (2020): 99–111.

Christopher James Peterson (petersoncj@ChurchofJesusChrist.org) was a principal at the Layton, Utah, Seminary when this was written.

Because Nephi was a highly participative follower, he was able to help lead his family to the promised land.

Because Nephi was a highly participative follower, he was able to help lead his family to the promised land.

“Who is the greatest leader who ever lived?” and “Who is the greatest follower who ever lived?” asked Stephen W. Owen, who in April 2016 was serving as the Young Men General President. The answer to both questions, he said, is Jesus Christ. “He is the greatest leader because He is the greatest follower. . . . In God’s eyes, the greatest leaders have always been the greatest followers.”[1] As religious educators, we are given various opportunities to lead, whether on our faculties or in our classrooms. Those seeking to improve their leadership ability have access to innumerable books, articles, lectures, online seminars, and other resources. One crucial and undervalued resource we can use to learn about and develop our leadership is the Book of Mormon.

The Book of Mormon was written by and about colonizers, kings, prophets, judges, and generals. From Nephi to Moroni, the primary characters of the book were leaders. Their successes and failures, along with their commitment to be led by God, gave them valuable leadership experiences, many of which were recorded and preserved for the benefit of future generations. Their leadership decisions followed a pattern that can be studied and emulated. Despite this, the Book of Mormon is strikingly and surprisingly absent as a source material on leadership.

Elements of many modern leadership styles, like transformational, humble, ethical, servant, and authentic leadership, can be found through a careful reading of the Book of Mormon.[2] While any of those leadership philosophies could have been analyzed, this article will focus on followership theory and how effective followership leads to improved leadership.

The purpose of this paper is twofold. First, using current followership research and the experiences of Nephi and his family, I will demonstrate how becoming more effective followers can help us become better leaders. Second, I will show that the Book of Mormon is a legitimate and valuable resource in leadership development. The Book of Mormon was not preserved to teach modern leadership styles, nor does its usefulness depend on how it does or does not connect to these leadership theories. However, an analysis of the leadership qualities and practices exhibited by leaders in the Book of Mormon could inspire religious educators to turn to the Book of Mormon more frequently for leadership guidance.

Followership Theory

In almost every instance, the righteous leaders in the Book of Mormon chose to act as they did because they were followers of Jesus Christ. This idea of leaders acting simultaneously as followers is referred to as followership[3] and is a growing field in leadership study. Because the leaders in the Book of Mormon were committed followers of the Savior Jesus Christ, they were more effective in their leadership. Their followership determined the degree of their leadership.

Modern studies in followership began in the early 1900s, but not until the 1980s did a more serious study of followership begin, and only in the last decade has it been recognized as a legitimate field of study.[4] Robert Kelley, one of the key voices in giving credibility to the study of followership, defined a follower as “one who pursues a course of action in common with a leader to achieve an organizational goal.”[5] Followers are most effective, he said, when they understand their own limitations in comparison with the leader’s authority and contribute to the success of the organization through accountability, purposeful decision-making, and the use of strong values and open dialogue. Followers do much more than walk behind. They are proactive participants in accomplishing a leader’s vision.

Recent scholarship has attempted to emphasize the dual nature of leader and follower roles. James Maroosis, a leadership professor at Fordham University, argued, “There are no leaders who are not followers, nor followers who are not leaders; both need to learn what and how to follow.”[6] Author Ernest Stech noted that leadership and followership “can be occupied at various times by persons in working groups, teams, or organizations.”[7] Those placed in positions of leadership who have not developed the ability to follow well are, at best, less-effective and, at worst, detriments to their organization.

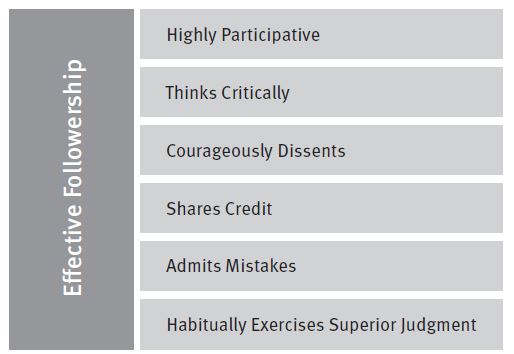

For some, the idea of followership is linked to words like passive, weak, and conforming. However, not all followers are created equal. Just as there are differing levels of leadership, there are also multiple stages of followership. A number of models exist,[8] but Kelley’s model begins with a group he labels “effective followers.”[9] This follower is “highly participative [and a critical thinker who] . . . courageously dissents when necessary, shares credit, admits mistakes, and habitually exercises superior judgment.”[10] His model includes four other types of followers, each with lessening degrees of effectiveness.[11] The type of follower you are has far more to do with choice than ability. Working to develop more effective followership in an organization provides the dual benefit of creating a more productive workforce and developing future leaders.

Followership versus Discipleship

Although the term follower is used in both the New Testament (see Ephesians 5:1; 1 Thessalonians 1:6) and the Book of Mormon (see 2 Nephi 28:14; Alma 4:15; Helaman 6:5; and Moroni 7:3) to describe man’s relationship to the Lord, a related and more common word used is disciple.[12] President James E. Faust taught that the word disciple “emphasizes practice or exercise. . . . It is primarily obedience to the Savior.”[13] The Savior’s invitation to his disciples has always been to follow him.[14] Both effective followers and disciples participate in a mentoring process that involves an element of discipline, work, and morality. It is worthwhile to consider how the principles of followership relate to what the Lord has revealed about discipleship.

There are important differences, however, between followership and discipleship. Understanding these differences will clarify the role of followership in the scriptures. First, being a disciple of Jesus Christ includes an element of worship that is crucial in a religious context and is absent from effective follower-leader relationships. Second, because we believe the Lord is perfect and that his ways and thoughts are higher than ours (see Isaiah 55:8–9), we follow with greater confidence than one would when trying to effectively follow a mortal leader.

Viewing our discipleship through the lens of followership can help us reflect on what kind of disciple we are. Can the Lord trust us with more responsibility and opportunity because we have proven that we can effectively follow? It could be fairly stated that the entire point of our mortal experience, the point of discipleship, is to learn how to effectively follow the Lord.

Nephi’s Unique Leadership Opportunity

Nephi’s followership is best understood in the context of his unique opportunity to lead and the way he viewed that leadership. He stated that part of his purpose in writing (decades after these events took place) was “to give an account . . . [of his] reign and ministry” (1 Nephi 10:1). He described himself reigning in an official capacity for only one chapter (see 2 Nephi 5). Before that, he enjoyed no official position in his family, group, or community. Why, then, did Nephi say that he would give an account of his reign and ministry? Nephi recognized that being a leader was not limited to formal positions and that he was leading throughout all his experiences. This is one of the defining features of effective followership. Understanding how Nephi viewed his father’s role as prophet and patriarch and how Nephi’s brothers reacted to his efforts to follow effectively will help us see how effective followership leads to more effective leadership.

Lehi—Patriarch and Prophet

At the outset of his record, Nephi made it clear that he was not the leader—Lehi was. The revelation regarding the destruction of Jerusalem came to Lehi, not Nephi. One day Nephi would act as prophet for God’s people. Initially, however, he recognized that his father filled that role. He purposefully included episodes that showed his father guiding the family (see 1 Nephi 1:4–5), offering correction (see 2 Nephi 1:14), continually receiving revelation (see 1 Nephi 3:2; 7:1; 8:2–33; 16:9; and 18:5), and fulfilling his patriarchal obligation as head of the family (see 2 Nephi 1–4). Lehi’s example of positive leadership qualities prepared Nephi to serve more effectively and provided a model for Nephi to follow.

Nephi included incidents in the story that demonstrated his deferral to his father’s leadership. For example, when trying to help his family obtain food, Nephi did what he could by making a new bow and arrow, but he refrained from doing the one thing he felt was outside his authority—obtaining revelation on behalf of the entire group. Turning to his father, he asked for him to petition the Lord on behalf of the family (see 1 Nephi 16:23). Nephi used this opportunity to sustain his father’s leadership.

Though Nephi’s efforts to lead frequently frustrated his older brothers, there is no evidence that Lehi ever felt threatened by Nephi. Lehi continued to trust Nephi to accomplish difficult assignments and commended him for being an effective follower (see 1 Nephi 3:8; and 2 Nephi 1). While fulfilling the Lord’s commands, Nephi acted simultaneously as a follower and leader—a difficult challenge. “It is an art,” author Ira Chaleff said, “to move fluidly between these roles and remain consistent in our treatment of others.”[15] Nephi was able to do that in part because Lehi’s leadership gave him a chance to be a better follower and prepared him for his own opportunity to lead.

Tensions Created by Nephi’s Leadership

Nephi’s leadership was a source of serious contention for his oldest brothers, who may have viewed his desire to follow effectively as a seditious power play. Culturally and scripturally, the firstborn son was to be the recipient of a favored land inheritance and the right to lead.[16] Brandt Gardner says that in the text, “Nephi continues to describe situations in which he is in violation of that cultural expectation.”[17] Laman and Lemuel were fully aware that culture dictated that they should lead and believed Nephi was defying that convention, saying, “Our younger brother thinks to rule over us; and we have had much trial because of him. . . . We will not have him to be our ruler; for it belongs unto us, who are the elder brethren, to rule over this people” (2 Nephi 5:3). If Nephi was trying to usurp power and bypass his brothers’ leadership, then Laman and Lemuel’s anger would have been justified.

Part of the problem was that Laman and Lemuel did not understand the important relationship between leadership and followership. Had they been more effective followers themselves, they may have seen that more easily. When the family was traveling across the sea and Laman and Lemuel, among others, began behaving in ways that displeased the Lord, Nephi courageously dissented, reminding his brothers of what was expected of them. His concern was for the safety of those on the ship (see 1 Nephi 18:10). However, they did “not hear his concern for their welfare, but rather his presumption.”[18] In anger they responded, “We will not that our younger brother shall be a ruler over us” (1 Nephi 18:10). Laman and Lemuel were overly sensitive about their position of leadership. Nephi did not say anything that presumed authority over them, yet all they could see was a mutinous younger brother.

Though Laman understood that he had the right to rule, he seemed to lack the responsibility of rule.[19] This failure is disappointing, because Laman had leadership ability. John Maxwell, a prominent leadership consultant and author, stated, “The true measure of leadership is influence.”[20] Laman exerted an enormous amount of influence over Lemuel, who “hearkened unto the words of Laman” (1 Nephi 3:28). He had similar influence over the sons of Ishmael (see 1 Nephi 16:37). That influence, however, was used in a way that hindered his family’s progress. He murmured about how hard God’s commandments were, while Nephi prayed to gain a testimony of them. Laman wanted to give up trying to get the plates after one attempt, whereas Nephi refused to do so. Laman complained about their lack of food, while Nephi encouraged his family to be faithful. Laman’s choices as a follower affected the type of leader he would become when he and Nephi finally separated.

While Nephi’s leadership was sanctioned by divine authority (a point his brothers seemed to choose to ignore), it was conditioned on his effectiveness as a follower: “And inasmuch as thou shalt keep my commandments, thou shalt be made a ruler and a teacher over thy brethren” (1 Nephi 2:22). Contrastingly, Laman and Lemuel were told by an angel, “Know ye not that the Lord hath chosen [Nephi] to be a ruler over you, and this because of your iniquities?” (1 Nephi 3:29). Nephi’s opportunity to lead and his brothers’ disqualification from leadership were directly tied to their ability to be effective followers of God.

Nephi’s Followership

Nephi consistently exemplified the essential characteristics of effective followership mentioned earlier. We will now look at specific instances where Nephi demonstrated what it looks like to be an effective follower. This will allow us to see how Nephi’s followership simultaneously allowed him to lead effectively and prepared him for future leadership opportunities.

Highly Participative

Effective followers seek to be part of the solution. They understand the big picture and are able to meet outcomes without having to be told exactly what to do.[21] Working under the guidelines they’ve been given, they diligently seek to accomplish their task. They aren’t discouraged when they encounter setbacks, and they do not make excuses.

When given a difficult assignment to fulfill, Nephi responded that he would “go and do the things which the Lord hath commanded” (1 Nephi 3:7). Interestingly, the Lord did not reveal in that moment exactly how to accomplish the task they were given. He allowed them to continue to seek inspiration and act. When they experienced failure and wanted to quit, Nephi encouraged them to continue working. “We will not go down unto our father in the wilderness until we have accomplished the thing which the Lord hath commanded us” (1 Nephi 3:15). Chris Musselwhite was describing followers like Nephi when he said, “Doing what needs to be done shows you understand and work toward the bigger picture.”[22] Nephi was an asset to his father and to the Lord because he understood the vision of what they were trying to accomplish and worked diligently to achieve it.

Later, when the entire family was struggling for want of food, Nephi again took initiative. While his brothers and father complained about their situation (see 1 Nephi 16:20), Nephi got to work (see 1 Nephi 16:23). As a result, he was able to receive additional guidance and save his family. Because Nephi was a highly participative follower, he was able to help lead his family to the promised land.

Thinks Critically

The ability to think critically without being critical is key to effective followership. When presented with challenges, effective followers seek to find the best answer. Training, instruction, and requests from leaders are given careful consideration and weight. Rather than accepting the easy option, effective followers put in the mental effort to find new solutions.

As Nephi was being taught by the Holy Ghost and angels, his responses to questions demonstrated a sincere effort to learn and a deep level of contemplation. Much of what Nephi learned was in response to the angel’s invitation to “look” and his own efforts to think critically (see 1 Nephi 11:8, 12, 19, 24, 27, 30, 31, 32; 12:1, 11; 13:1; 14:11, 19). When he did not fully understand, Nephi responded by expressing confidence in what he did know and admitting his lack of understanding (see 1 Nephi 11:17). “I know that [God] loveth his children; nevertheless, I do not know the meaning of all things” (1 Nephi 11:17). This attitude allowed him receive answers he needed and to share what he had learned with his family.

As followers are striving to think critically and gain greater understanding, a leader may not always choose or be at liberty to give all the reasons for his or her requests. This is one of the true tests of followership. James Maroosis explained how “there is something the follower does not know, that the follower cannot or will not see, that leadership brings to the relationship.”[23] For example, when the Lord commanded Nephi to make a second set of plates recording the history of his people, Nephi acknowledged that “the Lord [commanded him] to make these plates for a wise purpose in him, which purpose [he knew] not. But the Lord knoweth all things” (1 Nephi 9:5–6). Effective followers do not blindly obey every request of their leaders, but they do understand that there is certain information that leaders will not always be able to share.

Courageously Dissents

Leaders need people close to them who are able to recognize and are willing to tell them when they might be wrong. Effective followers help their leaders recognize when a specific method might be detrimental to the group, the leader, or the goal, or when the method is simply immoral. Effective followers do this not to criticize their leaders but because they care about the success of the group. This gives leaders an opportunity to rethink their decisions and make changes or to help their followers understand the reasons for their decisions.

Nephi followed his father and the Lord, but he also should have been led by Laman and Lemuel. As the eldest brothers, they had a responsibility to care for the physical and spiritual well-being of their family. Instead of passively standing by when they failed to live up to their familial obligations, Nephi called them out: “Behold, ye are mine elder brethren, and how is it that ye . . . have need that I, your younger brother, should speak unto you, yea, and be an example for you?” (1 Nephi 7:8). Nephi hoped that his dissent would help his brothers understand the danger of their decision (see 1 Nephi 7:15). They were initially angry because of his words, though they did eventually recognize that Nephi was right (see 1 Nephi 7:20–21).

Even when asked by the Lord to kill Laban, Nephi did not obey without consideration. Rather, he openly expressed his concern. This gave the Lord an opportunity to explain why that action was necessary. Nephi gained understanding; “therefore [he] did obey the voice of the Spirit” confidently (1 Nephi 4:18). Had he not questioned how killing Laban could be right and had simply obeyed, he may have always wondered if he had done the right thing. His willingness to courageously dissent gave him greater understanding.

Effective followers should not only have the courage to stand up to their leaders but also to stand up for them.[24] Followers who fear their peers more than their leader are bound to make wrong decisions in critical moments. Ira Chaleff explained: “It is important for a group to remember its leader’s strengths, which sometimes are forgotten or taken for granted. Whatever flaws a leader may have, her [or his] strengths may be holding the organization together or contributing significantly to the organization’s purpose. A courageous follower who encounters chronic complaining challenges the group to remember the leader’s strengths.”[25] When Nephi’s brothers questioned whether the Lord was capable of helping them retrieve the brass plates (see 1 Nephi 3:31), Nephi defended the Lord and extolled his strengths (see 1 Nephi 4:1). This attitude frequently inspired his brothers to act and helped the entire group move forward in the pursuit of their goal.

Shares Credit

Effective followers share credit rather than taking it for themselves. They understand that every member of the group plays an important role, and they openly recognize each member’s contributions. Doing so increases the morale and work ethic of the entire group. It also promotes a spirit of humility, which has been shown to significantly increase the productivity and effectiveness of an organization.[26]

Nephi recorded that his father “had fulfilled all the commandments of the Lord which had been given unto him” (1 Nephi 16:8), though clearly Nephi had done much of the work to accomplish them. Nephi could have taken more credit for retrieving the plates, saving his family from starvation, and building the ship. Instead he continued to say things like “We had obtained the records which the Lord had commanded us” (1 Nephi 5:21; emphasis added).

Admits Mistakes

Not only do effective followers humbly share credit, they also willingly admit their mistakes. This admission to self allows them to find ways to improve, and admitting mistakes to their leaders demonstrates accountability and builds trust. The admission is accompanied by a recognition of how their actions have negatively impacted the group and a plan for how they will act in the future.

As the writer of his book, Nephi could have left out any reference to his own weaknesses, yet he admitted how often he grieved “because of the temptations and sins which . . . so easily beset” him (2 Nephi 4:18). His humble confession of his own faults was followed by an expression of his confidence that God would assist him. He admitted that his heart initially needed softening when his father asked them to leave Jerusalem (see 1 Nephi 2:16). Rather than informing his readers that his bow broke, Nephi said, “I did break my bow” (1 Nephi 16:18).

Habitually Exercises Superior Judgment

Great followers are so effective because they consistently exercise superior judgment. They understand the goals and vision of their organization and make their decisions based on that understanding. They focus on long-term outcomes rather than short-term inconveniences. They continually seek to improve their understanding so they can make more informed decisions.

Laman and Lemuel were frequently focused on their immediate discomfort. They were angry about their lack of food, how hard they had to work, and how much they were suffering. This led them to desire to return to Jerusalem. Nephi, however, understood that returning would lead to their captivity and death. He knew what the Lord’s plan was. He reminded his brothers, “And if it so be that we are faithful to him, we shall obtain the land of promise; and ye shall know at some future period that the word of the Lord shall be fulfilled concerning the destruction of Jerusalem” (1 Nephi 7:13). Because he focused on the goal, he was able to make better decisions and help his family succeed in achieving the Lord’s plan.

Possessing these attributes in isolation doesn’t make one an effective follower. Nephi demonstrated that the elements of effective followership influenced one another and made him a more effective leader, even though he was not the official leader in any of the examples given above. Effective followers become natural choices in an organization when leadership positions must be filled. These individuals develop closer relationships with those in leadership roles because of their trustworthiness and dependability. Because they have proven they can follow effectively, they are frequently selected to fill “formal leadership positions over time,” Sharon Latour and Vicki Rast have explained. “More than any other measurable attribute, this phenomenon clarifies the interactive nature of the leader-follower relationship.”[27]

Nephi isn’t the only individual in the Book of Mormon to show the attributes of effective followership. Gideon’s relationship with King Limhi shows that he was a highly participative follower (see Mosiah 20:17–22; 22:3–9). The brother of Jared was a critical thinker (see Ether 3:1–5). Alma the Elder and Lamoni both courageously dissented when their leaders were making the wrong choice (see Mosiah 17:2; Alma 20:14–15). Moroni shared credit with the Lord when his enemies believed that he was victorious in battle because of his cunning and armor (see Alma 44:3–5, 9). These examples—and more—demonstrate how the greatest leaders are also the greatest followers.

Conclusion

Nephi was such a remarkable leader because he was such an effective follower. His efforts to be highly participative, think critically, share credit, and so forth helped his group to succeed and prepared him for future leadership opportunities. As religious educators study the Book of Mormon, we can identify other examples of leadership to emulate. We will observe how effective followership helped individuals in the scriptures become better leaders. We will also recognize that as we strive to be more effective followers in our current assignments, we will develop attributes that will allow us to become more effective leaders and more faithful disciples of Jesus Christ.

As in all things, Christ is our perfect example. He submitted to the will of the Father from the beginning (see Moses 4:1–2). He did only those things which he saw the Father do (see John 5:19). He gave credit to God rather than taking it for himself (see Mark 10:18). Because he followed his Father with such fidelity, Christ could ask the same thing of his followers. Christ was so good at modeling this that someone seeking to follow the Savior would have to follow the Father also. As Nephi taught, “Can we follow Jesus save we shall be willing to keep the commandments of the Father?” (2 Nephi 31:10). Christ is the greatest leader because he is the greatest follower.

Notes

[1] Stephen W. Owen, “The Greatest Leaders are the Greatest Followers,” Ensign, May 2016, 70, 75.

[2] This is because the principles of effective leadership are not man-made inventions but eternal principles. God has been inspiring Christlike leaders for thousands of years. Modern leadership scholars are now putting names and descriptors to the elements of leadership that were already being lived.

[3] James Maroosis, “Leadership: A Partnership in Reciprocal Following,” in The Art of Followership: How Great Followers Create Great Leaders and Organizations, ed. Ronald E. Riggio, Ira Chaleff, and Jean Lipman-Blumen (San Francisco: Wiley & Sons, 2008), 18.

[4] Laurie J. Barclay, “Following in the Footsteps of Mary Parker Follett: Exploring How Insights from the Past Can Advance Organizational Justice Theory and Research,” Management Decision 43, no. 5 (2005): 741–742. Mary Parker Follett pioneered many ideas, but for a variety of reasons (including gender discrimination and scholarship bias), her ideas were not given much credence.

[5] Robert E. Kelley, “In Praise of Followers,” in Military Leadership: In Pursuit of Excellence, ed. Robert L. Taylor and William E. Rosenbach, 3rd ed. (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1996), 137.

[6] Maroosis, “Leadership,” 18.

[7] Ernest L. Stech, “A New Leadership-Followership Paradigm,” in The Art of Followership, 47.

[8] Rodger Adair, “Developing Great Leaders, One Follower at a Time,” in The Art of Followership, 137–53.

[9] Kelley, “Praise,” 137.

[10] Kelley, “Praise,” 138–41.

[11] Passive followers, or sheep, do what they are asked but no more. They lack the motivation or ability to proactively contribute. Conformists, or yes-people, are anxious to follow the leader, detrimentally so. They give no helpful council but are merely content to not contradict their superiors. Alienated followers, the disgruntled, think independently but are unmotivated because they have become disenchanted with the leader or organization. The Pragmatics are prepared to be the type of follower that best fits the situation. Motivated often by a desire to not have to put forth too much effort, the Pragmatists’ effectiveness, as well as their loyalty, is transient. Followers in each category exist in every business, team, or religious group but can also exist simultaneously in the same person. Future work could identify how each of these types of followers appears in the Book of Mormon. See Kelley, “Praise,” 137.

[12] See Matthew 10:1; John 8:31; John 13:35; John 15:8; 3 Nephi 5:13; and 3 Nephi 15:12. The Greek word for disciple is mathētēs, meaning a learner or pupil, while the word for follower is mimētēs, meaning imitator. Both words indicate a process of becoming like the one being followed. Blue Letter Bible (website).

[13] James E. Faust, “Discipleship,” Ensign, November 2006, 20.

[14] See Matthew 4:19. Examples of the Savior inviting others to follow him include the following: when certain disciples demonstrated that the Savior and his gospel were not their first priority he rebuked them (see Matthew 10:38; and Doctrine and Covenants 56:2) and told them to take their cross (see Matthew 16:24), sell what they had, and follow him (see Matthew 19:21). Nephi understood how effective followership was critical to discipleship. He urged those he taught to “follow the Son, with full purpose of heart” (2 Nephi 31:13). Nephi’s life and teachings demonstrate an advanced understanding of the importance of being effective followers of our Savior.

[15] Ira Chaleff, The Courageous Follower: Standing Up to and for Our Leaders (Oakland: Berrett-Koehler, 2009), 37.

[16] Daniel N. Rolph, “Prophets, Kings, and Swords: The Sword of Laban and Its Possible Pre-Laban Origin,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2, no. 1 (1991): 76.

[17] Brant A. Gardner, 1 Nephi, vol. 1 of Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 254.

[18] Gardner, 1 Nephi, 317.

[19] James M. Burns, Leadership (New York City: Harper & Row, 1978), 1. Burns says, “The crisis of leadership today is the mediocrity or irresponsibility of” those who should be leading.

[20] John C. Maxwell, The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership (Nashville: Nelson, 2007), 11.

[21] See Doctrine and Covenants 58:26–28. The Lord teaches the members of the Colesville branch what it looks like to be an true disciple of Christ, and it is the same as what is required to be an effective follower.

[22] Chris Musselwhite, Why Great Followers Make the Best Leaders (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2006), 3

[23] Maroosis, “Leadership,” 18.

[24] Chaleff, Courageous Follower, 62

[25] Chaleff, Courageous Follower, 62.

[26] Jim Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap . . . And Others Don’t (New York City: HarperCollins, 2001), 20–21. In his book, Jim Collins presents his research that has found that the difference between great leaders and good ones has a much to do with their level of humility. He asserts that there are five levels of leadership, and very few executives achieve the fifth level of managerial success, though the most successful companies were all led by one of these level five leaders. One of the common traits they all possessed was “a compelling modesty.” These leaders possessed the unusual combination of “personal humility and professional will” that allowed them to be great followers. Those at a level 4 tended to hurt the continued prosperity of their organization because of their prideful pursuits. The most effective leaders have a degree of humility that is absent in good leaders.

[27] Sharon M. Latour and Vicki J. Rast, “Dynamic Followership: The Prerequisite for Effective Leadership,” Air & Space Power Journal 18, no. 4 (2004): 105.