Twenty Years of the Religious Educator

Brad Wilcox and Timothy G. Morrison

Brad Wilcox and Timothy G. Morrison, "Twenty Years of the Religious Educator," Religious Educator 21, no. 1 (2020): 13–29.

Brad Wilcox (brad_wilcox@byu.edu) was an associate professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this was published.

Timothy G. Morrison (timothy_morrison@byu.edu) was an associate professor of teacher education at BYU when this was published.

Readership has grown to include faculty members from various fields across the BYU campus, Church members, lay leaders, and even incarcerated readers.

Readership has grown to include faculty members from various fields across the BYU campus, Church members, lay leaders, and even incarcerated readers.

Where were you twenty years ago? That was before the terrorist attacks of 2001 and the heightened airport security that followed. Do you remember when the vote between George W. Bush and Al Gore dangled on a few hanging chads in Florida? President Gordon B. Hinckley was the President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 2000 and dedicated the Conference Center in Salt Lake City. Faith Hill was singing “Breathe,” and the Yankees beat the Mets in the 2000 World Series. The Sixth Sense was an Oscar-nominated movie that had us on the edge of our seats. A lot happened back in the year 2000, but perhaps something that may have escaped your notice was the beginning of a journal at Brigham Young University called the Religious Educator. From that beginning, the journal has grown to be a significant resource for gospel scholarship throughout the world.

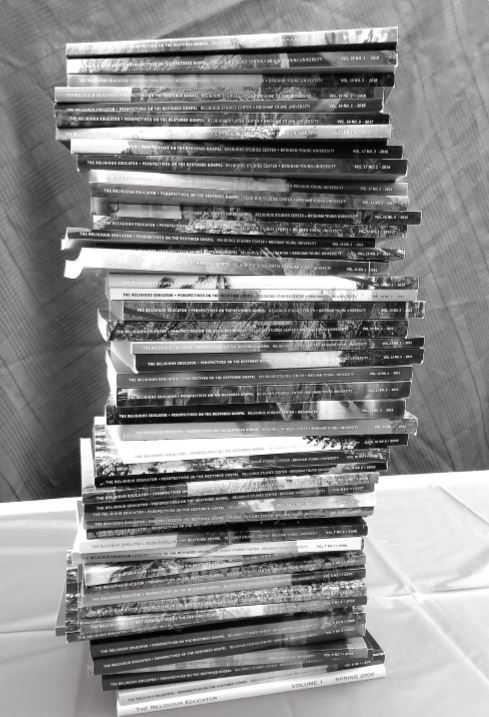

The Religious Educator is celebrating its twentieth anniversary. This unique journal focuses on topics of interest to faithful Latter-day Saints and is used throughout the universities, institutes, and seminaries of the Church. It is published by the Religious Studies Center (RSC) at Brigham Young University.

The primary purpose of this article is to complete a brief history of the journal and report results of an analysis that documented topics that are reflected in the articles published in the Religious Educator. A secondary purpose is to examine authorship patterns in the journal. Similar research has been completed in other fields. For example, literacy researchers have completed content analyses of professional journals on multiple occasions.[1] The importance of this work has been underscored by Baldwin and others, who believed that systematic analysis of historical trends in journals reveals influences in any given field that would otherwise remain buried.[2]

Starting the Journal

The history of this journal provides a helpful context in which to understand its purposes and direction. The information shared here is based on seven interviews with individuals who have been associated with the journal: Robert L. Millet, Richard N. Holzapfel, Ted D. Stoddard, R. Devan Jensen, Brent R. Nordgren, Dana M. Pike, and Thomas A. Wayment. These interviews were completed between January and April 2017.

In the past, Religious Education sponsored a number of graduate programs, which allowed professors and students to engage in scholarship. On 3 May 1972, Religious Education discontinued its doctoral degree programs. This gave fewer opportunities for faculty to team with students in scholarly research. As a faculty member at the time, Robert L. Millet noticed the resulting decline in faculty scholarly productivity. When he became dean in 1991, he began meeting with Stanley A. Peterson, who was the associate commissioner/

Robert L. Millet proposed launching a journal to motivate increased scholarship.

Robert L. Millet proposed launching a journal to motivate increased scholarship.

Some believed the journal was not needed because BYU Studies was already well established. However, Millet felt that BYU Studies’ focus was quite broad, attempting to serve multiple departments and programs across the university. He defended the need for an additional journal to specifically address gospel teaching, doctrinal understanding, and Church history. He wanted the journal to offer pedagogical help but also present doctrine in a way that would provoke serious thinking and scholarship.

In 2000, only one issue was produced. It was edited within Religious Education, primarily by Andrew C. Skinner, the editorial manager and chair of the Department of Ancient Scripture at the time, and Lori A. Soza, an administrative assistant, with help from Connie R. Lankford, Laura Card, and Cory Crawford. This first issue contained three articles having to do with teaching the gospel, four related to scripture and doctrine, two under the heading of Church history, and one article described as devotional. In addition, three poems were included in the issue. The first issue was met with a positive response, and Millet determined to continue publication of the journal, with two issues in the following year and three issues each year thereafter.

One obstacle in producing the journal was that the required workload was in addition to current job expectations. Dean Millet assigned associate dean Paul Y. Hoskisson to explore options for making journal production part of a faculty member’s job assignment. Hoskisson invited Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, professor of Church history and doctrine, to take on production of the journal as part of his full-time responsibilities and bring the journal under the supervision of the RSC. Specifically, Hoskisson asked Holzapfel to increase the rigor of the journal and clarify its purpose within the Latter-day Saint community. Previously, professors had tailored their writing for BYU Studies or the Ensign, an official publication of the Church. BYU Studies had a general academic focus, while the Ensign was aimed at general Church membership. Holzapfel envisioned the Religious Educator as finding a home somewhere between these two publications, with a particular focus on gospel teaching. He also wanted to align the journal with the stated aims of a BYU Education: spiritually strengthening, intellectually enlarging, character building, and leading to lifelong learning and service. To help achieve those aims, Holzapfel determined to focus on teaching and scholarship and to publish addresses by General Authorities that had not been published elsewhere. He also wanted to improve the design of the journal, giving it a more professional appearance. He approached Stephen Hales, a professional designer, and Ted D. Stoddard, a business writing professor at BYU. Hales agreed to work on the graphic aspects of the journal at a discounted rate, and Stoddard accepted the invitation to be an associate editor, without compensation. To attract contributors, Holzapfel reached out to full- and part-time seminary and institute teachers, as well as faculty within Religious Education.

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel was tasked to take on production of the journal and bring it under the supervision of the RSC.

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel was tasked to take on production of the journal and bring it under the supervision of the RSC.

As more manuscripts began to be submitted, Holzapfel realized that a review process needed to be established that reached beyond the editors. He identified qualified individuals who could serve as reviewers in a blind, peer-review process that is typical in professional publications. In addition, because of the religious nature of the content, he felt the need to establish a review board that included trusted voices within the Church community, including Elder Tad R. Callister and Kathy Kipp Clayton. The review board was tasked with ensuring that the journal maintained an appeal to mainstream Church members and avoided topics that might be considered fringe or extreme. Mary Jo Tansy of the BYU Creative Works office handled distribution of the journal. Charlotte Pollard, an administrative assistant in the RSC, and later Joany Pinegar, the publications coordinator for the RSC, helped coordinate the peer-review process.

In 2001, R. Devan Jensen, who had worked as an editor for the Ensign at the time, was hired by the RSC to oversee book editing and edit the redesigned Religious Educator. This team of Holzapfel, Stoddard, Jensen, and Hales worked together for ten years to publish the journal, with Jensen handling the editing and Kelly Nield designing and typesetting. In 2004, Holzapfel became the publications director of the RSC, which included continuing as editor of the Religious Educator. In 2008, Brent R. Nordgren joined the team as a production supervisor, securing images, captions, and permissions. In 2010, Holzapfel received a call to serve as mission president in Alabama. This required a change in leadership of the RSC and editorship of the Religious Educator. Robert L. Millet, no longer serving as dean, replaced Holzapfel from 2010 to 2012 with the assistance of Richard E. Bennett, associate dean of Religious Education. Dana M. Pike, professor of ancient scripture, was the next editor of the journal until the end of 2013. The following year, Thomas A. Wayment, professor in the Department of Ancient Scripture at the time, became publications director of the RSC and editor in chief. He was followed in 2018 by Scott C. Esplin, professor in the Department of Church History and Doctrine.

Methods

The authors of this article examined published articles in the Religious Educator, covering the period from 2000 through 2019, including 627 articles. The analysis included only published articles, both reviewed and invited, and interviews. Excluded were book reviews, editorials, and poems. Title and year of publication for each article were entered onto an Excel spreadsheet, along with authors’ names, so frequency counts of individual authors could be completed. The number of articles written by multiple authors was also tabulated.

The researchers recorded one subject descriptor (one or more words) for each article based on themes in the title, subtitles, or headings of the article. Two researchers examined each article together to ensure agreement. Differences in opinion were resolved through discussion. Further inter-rater reliability was not required, since two researchers worked side by side on all articles. Following initial decisions, all data were rechecked by the same researchers to ensure correctness and completeness.

In addition to assigning one subject descriptor for each article, the researchers identified between one to ten key words (total of 2,438) to describe the content of each article in more depth. These key words were subordinate to the subject descriptors and were identified using a similar procedure to that used to identify the subject descriptors. A uniform number of key words was not used for each article, because the articles varied in topic, length, depth, and breadth. To manage this large amount of data, the researchers listed all key words alphabetically, and then created categories by combining key words that were semantically similar. For example, adversity (n=4), opposition (n=2), refiner’s fire (n=1), and trials (n=2) were grouped under the category of adversity (n=9). Misbehavior (n=1), disruptions (n=1), difficult pupils (n=1), and high expectations (n=1) were combined within the category of discipline (n=4). The total frequency counts of all categories were tabulated and listed in order from greatest to least. This process is similar to that used by Baldwin and others and Morrison and others as they conducted content analyses of other professional journals.[3]

Results and Discussion

The following section presents and discusses results. First, findings for authors are presented, followed by subject descriptors and key words.

Authors

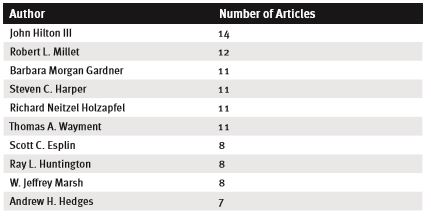

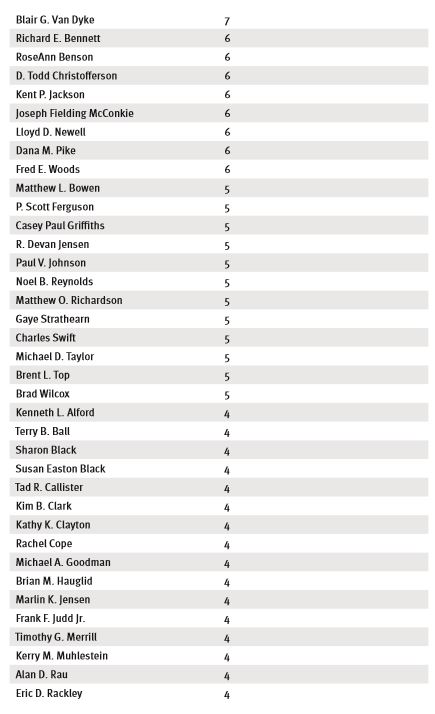

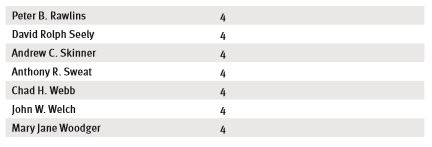

Table 1 shows the most prolific authors in the Religious Educator from 2000 to 2019. One author was most prolific, publishing fourteen articles, John Hilton III. Robert L. Millet was second with twelve articles. Millet was involved with the journal from its beginnings, having published an article in the first issue. Hilton’s first Religious Educator article was published in 2008. Four authors tied for third: Barbara Morgan Gardner, Steven C. Harper, Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, and Thomas A. Wayment, with eleven articles each.

In the first issue of Religious Educator all articles were written by single authors. The first article written by two authors appeared during the second year. The first article written by more than two authors appeared in 2005. Of the 627 total articles, 530 (85 percent) were written by single authors, 73 (12 percent) by two authors, only 12 (1.9 percent) by three authors, seven (1.1 percent) by four authors, and five (0.8 percent) by five authors. The overwhelming number of single-authored articles is not consistent with authorship trends in journals from other disciplines. For example, Morrison and others found that in literacy education journals from the 1960s to the 2000s the percentage of multiple-authored articles increased from 13.8 percent to 63.4 percent.[4] Similar trends have been documented in bioethics[5] and periodontal journals[6] It would be interesting to know the authorship trends in journals more closely related to Religious Educator, such as biblical and religious studies, however, the researchers were not able to find any studies that had focused in these areas in our literature review.

One possible reason for the pattern of increased coauthorship in other fields may be that leaders have come to recognize coauthorship as evidence of both synergy and collegiality. It may also be a response to administrators’ consistent pressure on university faculty members to publish. Although these reasons are extrinsic and utilitarian, an intrinsic explanation may be that researchers themselves have come to value collaborating with peers in cooperative efforts and learning communities. This does not seem to be the case in the Religious Educator, in which single-authored pieces are more prevalent.

One obvious concern that surfaced was the underrepresentation of women as authors. Women have been published since the first issue, but among the fifty-four most prolific authors only eight were women. Authors outside BYU are also underrepresented. Seminary and institute teachers do not have the same expectation to publish as BYU faculty members. However, because they are a major target audience, more could be done to invite their participation as contributing authors.

Subject Descriptors

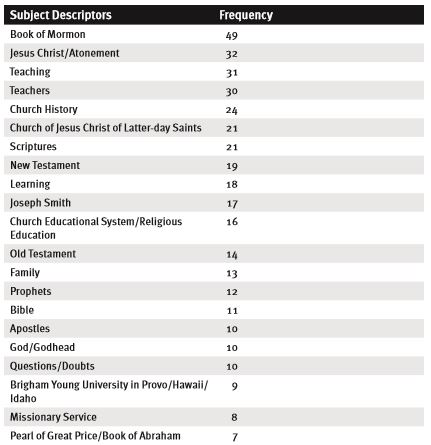

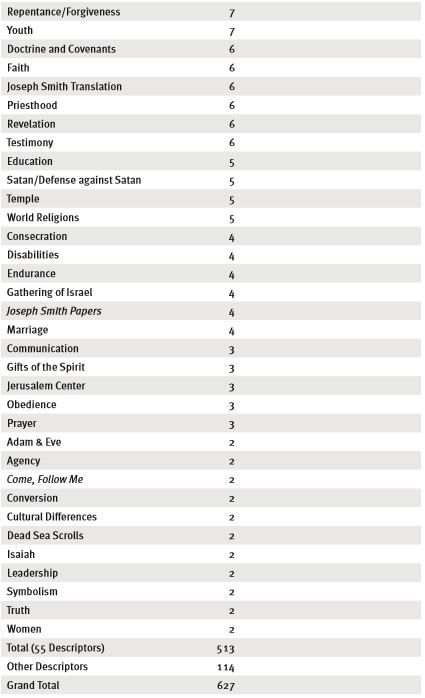

Table 2 shows the frequencies and percentages of subject descriptors used in the articles published in Religious Educator. Of the 627 total articles, 55 descriptors were used for 513 of them, almost 82 percent, and 114 articles had a unique descriptor. Examples of these unique descriptors are callings and releases, collaborating with other churches, Deseret Alphabet, divinity of women, Feast of the Tabernacles, habits, optimism, priorities, religious freedom, Revolutionary War, seal of Melchizedek, secondhand smoking, and writing a sacrament meeting talk.

The journal includes a wide range of topics that surface multiple times. The most frequently occurring topic was the Book of Mormon (n=49), which accounted for 7.81percent of all articles. Within that topic, articles dealt with doctrine, geography and archaeology, and witnesses and evidences. The next most frequent topics were Jesus Christ/

According to Robert L. Millet, the original focus of the journal was to be on gospel teaching, doctrinal understanding, and Church history. Of the fifty-five total descriptors in table 2, virtually all of them fit into at least one of those three categories.

All four of the standard works surfaced as predominant topics, along with prophets and apostles. The topics God and Jesus Christ were also prominent, however, few articles focused solely on the Holy Ghost. There were articles about the gifts of the Spirit and teaching by the Spirit, but no subject descriptors about the third member of the Godhead. However, when key words were considered, both Holy Ghost and Gift of the Holy Ghost appeared as subtopics within broader subject descriptors.

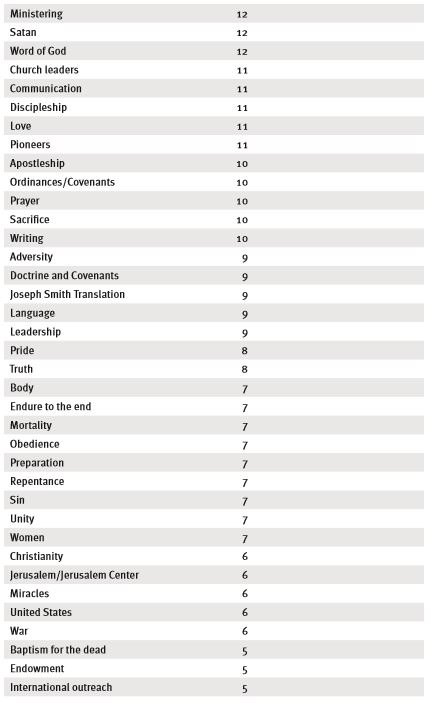

Key Words

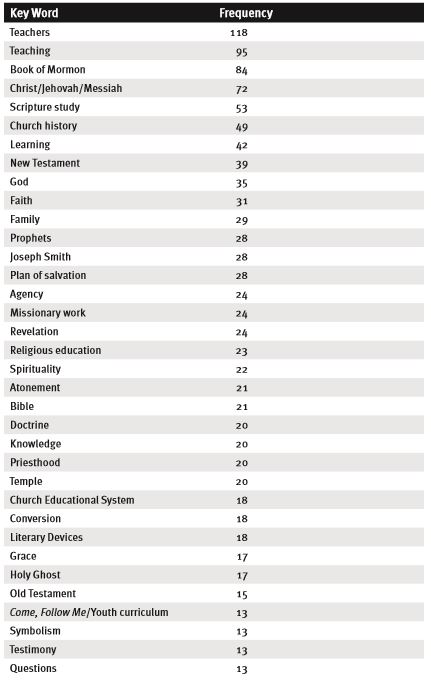

One to ten key words were selected based on the content of each article for a total of 2,438 key words. The most prevalent key word by far was teachers (n=118), followed by teaching (n=95). The next most-used key words were Book of Mormon (n=84), Christ, (n=72), scripture study (n=53), Church history (n=49), learning (n=42), New Testament (n=39), and God (n=35). These nine key words accounted for 24 percent of all key words. The frequencies and percentages of key words used five times or more are shown in table 3.

Teachers, teaching, scripture study, and learning were within the top seven key words. Not only do these key words align with the title, audience, and original pedagogical purposes of the journal, but they also reflect changes within the general handbooks of the Church since 2009, when the words learning and teaching were linked together and given greater emphasis. Book of Mormon, New Testament, and Church history are key words that reflect the journal’s original intent to address gospel teaching, doctrinal understanding, and Church history. They also reflect the seminary and adult Sunday School curriculum. It is also significant that the key words Christ and God were among the most prevalent since they are the focus of religious educators throughout the Church. The next five key words show an emphasis in the journal on essential doctrines: faith, family, prophets, Joseph Smith, and plan of salvation. The prevalence of Joseph Smith is not surprising, but it is interesting that he surfaces during twenty years in which more and more information has become available about him through sources such as The Joseph Smith Papers. Similarly, the prominence of family is not surprising when one considers that over the twenty years of publication there has not only been great effort to redefine family in society, but also an increased focus on strengthening family in the Church. This key word appears to reflect the family proclamation and the creation of a cornerstone class on the family in institutes and Church universities.

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel stressed that the articles in Religious Educator should align with the stated Aims of a BYU education. The authors subjectively categorized the seventy-five most predominant key words according to the four stated Aims. About half were deemed to be spiritually strengthening, and the others fell largely into the categories of intellectually enlarging and building character. Lifelong learning and service was the least represented. Perhaps this indicates that authors of articles in the journal need to make a greater effort to connect their writing to applications in real-life settings.

Key words reflected topics that received attention, as well as those that did not. Considering the stated purposes of the journal, perhaps there needs to be a greater effort to include more articles on the Old Testament and the Doctrine and Covenants. Motherhood and women in the Church are topics that could also receive additional attention in future issues.

Teachers, teaching, scripture study, and learning were within the top seven key words.

Teachers, teaching, scripture study, and learning were within the top seven key words.

Conclusion

Over the past twenty years, the Religious Educator seems to have been successful in addressing its aims. It has proven to be a consistent publication outlet for Latter-day Saint authors. Based on the number of articles, the journal has indeed been a motivation for religious scholarship, as was initially intended. The original target audience was religious educators, including seminary and institute teachers, both full- and part-time. Readership has grown to include faculty members from various fields across the BYU campus, Church members, lay leaders, and even incarcerated Latter-day Saints. One inmate received the journal and reported that it was read cover-to-cover by him and other incarcerated members who described it as “the Ensign on steroids.” Members of other faiths have also found the journal to be a “positive influence” and “a fascinating view inside Latter-day Saint beliefs and practices.”[7] More could be done to examine how readers are using the journal and what additional feedback they might have so that it can better meet diverse needs.

Initially, the three areas of focus for the journal were outlined as gospel teaching, doctrinal understanding, and Church history. Articles in the journal continue to reflect these original categories. In this regard, the journal has stayed remarkably true to its mission statement—something that cannot be said of all professional journals. One additional focus that appeared quickly in the Religious Educator was to include articles by and interviews with General Authorities and officers of the Church. Often, these have been adapted from addresses given at various conferences or reprints of devotional addresses. For example, volume 2, issue 1 included an article by Elder D. Todd Christofferson, “The Faith of a Prophet: Brigham Young’s Life and Service—A Pattern of Applied Faith.” In issue 2 of the same year, articles appeared by Elder Henry B. Eyring (“We Must Raise Our Sights”) and Elder Merrill J. Bateman and his wife, Sister Marilyn Bateman (“Lay Hold upon Every Good Thing”). Although articles such as these have been included in the journal without undergoing a peer-review process, they have provided great depth and substance to the content of the journal, along with an authoritative voice that is respected and valued by readers.

At the university conference in Provo in 2016, Elder Kim B. Clark, Commissioner of Church Education and General Authority Seventy at the time, highlighted two assignments of the Church Educational System. He said, “First, we need to educate more deeply and more powerfully than we have ever done before—more than anyone has ever done before. . . . Second, we have a sacred responsibility to do all we can to help many more of the rising generation and many of the older generation to obtain that kind of education.”[8] This content analysis of the first twenty years of the Religious Educator has shown that the journal is a valuable tool in fulfilling these two assignments and building the kingdom of God.

Notes

Notes

We offer special thanks to Braden Goimarac, Jake Robins, Makayla Lake, Matthew Lamattina, Joel Rosario, and Spencer Wright for their help with interviews and the research process.

[1] R. Scott Baldwin et al., “Forty Years of NRC Publications: 1952–1991,” Journal of Reading Behavior 24 (1992): 505–32; Ron P. Carver and Edward B. Fry, “Looking Back and Looking Forward” (presentation at the meeting of the National Reading Conference, Palm Springs, CA, December 1991); Barbara Guzzetti, Patricia L. Anders, and Susan Neuman, “Thirty Years of JRB/

[2] Baldwin et al., “Forty Years of NRC Publications,” 505–32.

[3] Baldwin et al., “Forty Years of NRC Publications,” 505–32; Timothy G. Morrison et al., “50 Years of Literacy Research and Instruction: 1961–2011,” Literacy Research and Instruction 50, no. 4 (2011): 313–26.

[4] Morrison et al., “50 Years of Literacy Research and Instruction,” 313–26.

[5] Pascal Borry, Paul Schotsmans, and Kris Dierickx, “Author, Contributor, or Just a Signer? A Quantitative Analysis of Authorship Trends in the Field of Bioethics,” Bioethics 20, no. 4 (2006): 213–20.

[6] Alessandro Geminiani et al., “Bibliometrics Study on Authorship Trends in Periodontal Literature from 1995 to 2010,” Journal of Periodontology 85 no. 5 (2014): 136–43.

[7] Personal communication to authors from Brad Platt, 2015.

[8] Kim B. Clark, “The Lord’s Pattern” (Brigham Young University conference address, 22 August 2016), https://