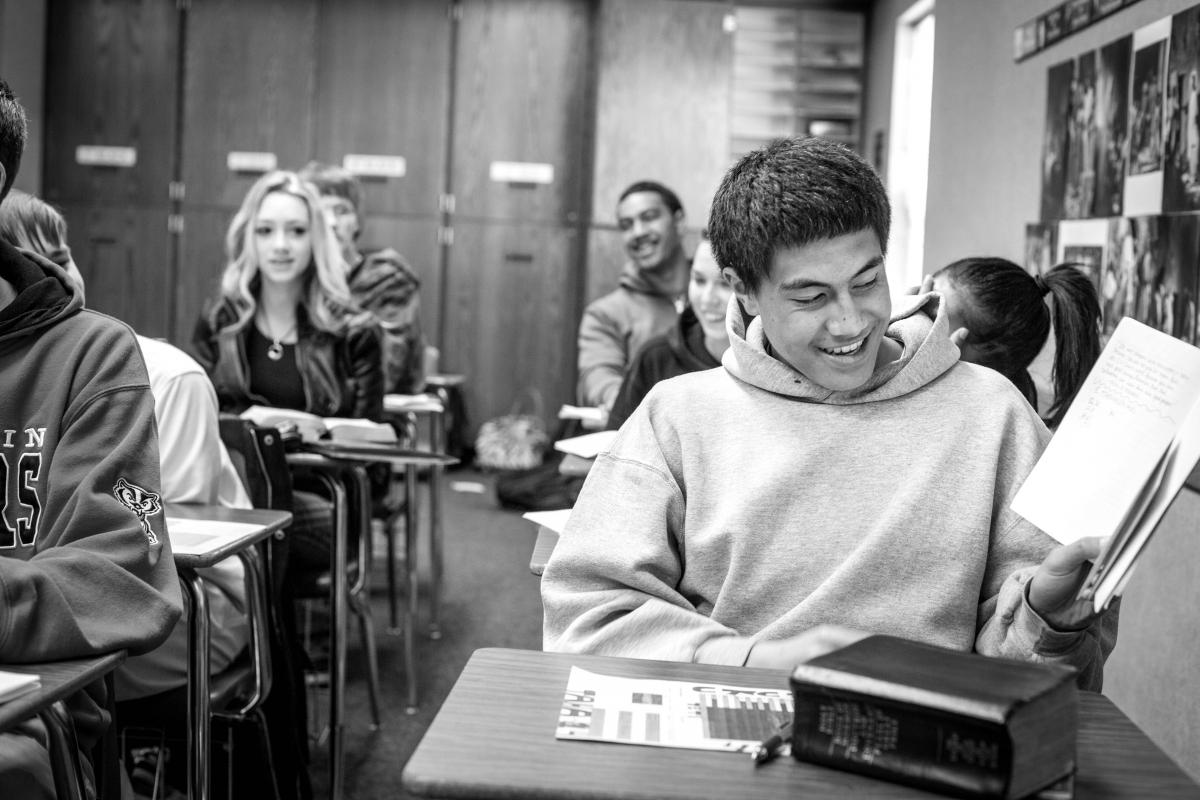

A Jershon Classroom

Scott Royal Bagley

Scott Royal Bagley, "A Jershon Classroom," Religious Educator 21, no. 1 (2020): 75–85.

Scott Royal Bagley (bagleysr@ChurchofJesusChrist.org) was an instructor at the Monroe Utah Seminary when this was published.

These youth are spiritual refugees, and they need a Jershon classroom to come to and receive the acceptance, care, peace, and hope they long for.

These youth are spiritual refugees, and they need a Jershon classroom to come to and receive the acceptance, care, peace, and hope they long for.

A powerful tool for recruiting students can be our classroom environment. The scriptures give us a wonderful example of this idea. After the people of Ammon are given the land of Jershon, they are soon joined by religious refugees from among the Zoramites (Alma 35:6–9), fugitives from among the Lamanites (Alma 47:29), and Lamanite wartime prisoners (Alma 62:17, 27–29). The people of Ammon accept all of these people as their own. But the question is this: what was it about the people of Ammon that attracted these societal refugees? As we examine the people of Ammon and how they cared for refugees, we will see how we can incorporate similar care for our students into our classrooms. We can cultivate an environment that is safe, welcoming, and edifying.

Spiritual Refugees

The Anti-Nephi-Lehies, hereafter called the people of Ammon, find themselves in a situation that is not ideal. They cannot stay on their land because Amalekite aggression has peaked, and destruction is looming over the people of Ammon. Ammon presents the idea that they could “go down to the land of Zarahemla to . . . the Nephites” (Alma 27:5). This is also problematic, at least in the eyes of the king, for he thinks “the Nephites will destroy us, because of the many murders and sins we have committed against them” (Alma 27:6). After Ammon inquires of the Lord and receives his approval for the decision to leave, the people of Ammon travel north into the land of the Nephites. Cast out of their lands, society, and previous lifestyles, they are refugees.

In an act of Christlike love, the Nephites give up the land of Jershon, “east by the sea” and “south of the land Bountiful,” and this land, the Nephites say, they give “for an inheritance” (Alma 27:22).

All we know about this land is the brief blip that Mormon gives us: “east by the sea” and “south of the land Bountiful.” And while that does not paint a vivid landscape for the reader, perhaps Mormon was intending us to look beyond the geography of Jershon and see deeper into what Jershon was rather than where it was.

What was this land to those who were in similar situations to the people of Ammon—refugees of war and religious persecution? It provided a beacon of hope and stability to the many different people who fled to that land. Jershon was full of people who were once Lamanites, sought for a better life, and could now freely live it without fear and without hindrance. For the Zoramite refugees, in Alma 35:6–9, it was a land of opportunity, a chance to leave behind the fiscal and spiritual poverty they experienced in Antionum, to become stronger, and to be accepted, loved, and seen as equals. For the servants of the king of the Lamanites in Alma 47:29, Jershon meant a land of safety and security; they could go from fugitives to “fellowcitizens with the saints, and of the household of God” (Ephesians 2:19). For the Lamanite wartime prisoners in Alma 62:17, 27–29, who had spent years fighting, this was a land of peace and rest.

Youth today experience difficult events in their lives. Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, in his most recent address to Seminaries and Institutes personnel, “Angels and Astonishment,” referred to research done about the challenges the youth are facing. In that portion of his address, he quotes James Emery White, pastor and author, who states that two things define the spiritual circumstance of youth today (as a whole, not necessarily only in the Church): “They are lost . . . [and] they are leaderless.”[1] These youth are spiritual refugees, and they need a Jershon classroom to come to and receive the acceptance, care, peace, and hope they long for.

Elder Kim B. Clark has expressed that our classrooms need to be “psychologically, emotionally and spiritually safe.”[2] As with the refugees who sought out the people of Ammon in the land Jershon in the Book of Mormon, fear is the sentiment that drives today’s youth toward safety (see Alma 47:29). According to Elder Ronald A. Rasband, those fears have psychological, emotional, and spiritual elements:

Fear of not being accepted by friends. Fear of academic performance, pressures, and problems at home they can’t solve. Fear that they can trust no one and no one trusts them. Fear of being alone, and fear of being in groups. Fear that they are a burden to others. Fear of organized religion or any religion. Fear that there is no solution or relief to their pain. Fear prompts discouragement and despair, anxiety and depression; fear fuels frustrations that have no good conclusion. Fear believes that no one will understand and, worse yet, that no one even asks, “What’s the matter?”[3]

When these refugees come to our Jershon classrooms, we can ensure that, like the people of Ammon, we “receive all the poor,” “nourish them,” “clothe them,” “give unto them lands for their inheritance,” and “administer unto them according to their wants” (Alma 35:9). These four areas of care—nourishing, clothing, giving them a place, and administering—can create an environment where youth (enrolled or not, and perhaps even not members of the Church) will want to come, stay, learn, and grow closer to the Savior, Jesus Christ.

Nourishing Youth

Moroni mentions that all people, when they come unto Christ, need to be “nourished by the good word of God” (Moroni 6:4). Likewise, when youth, spiritual refugees, come to our Jershon classrooms, they are in need of nourishment.

Nourishing entails strengthening and empowering by slowly and steadily, consistently and continuously, making someone or something better. In the context of health, nourishing is different than simply feeding. Elder Jeffrey R. Holland illustrated the contrast between the two:

When crises come in our lives—and they will—the philosophies of men interlaced with a few scriptures and poems just won’t do. Are we really nurturing our youth and our new members in a way that will sustain them when the stresses of life appear? . . .

During a severe winter several years ago, President Boyd K. Packer noted that a goodly number of deer had died of starvation while their stomachs were full of hay. In an honest effort to assist, agencies had supplied the superficial when the substantial was what had been needed. Regrettably they had fed the deer but they had not nourished them.[4]

Nourishment, the kind that can be provided only from the scriptures, “healeth the wounded soul” (Jacob 2:8). How can we effectively provide nourishment to students through the word of God?

Elder Kim B. Clark has taught this dynamic statement, “In a very powerful way, how you teach is what you teach your students.”[5] How we use the scriptures and words of the prophets in class will encourage students to study them prayerfully and apply the principles therein courageously; the youth will be able to nourish themselves. In the Gospel Teaching and Learning handbook, we read that teachers must “respect and reverence [the word of God] and the words of His prophets in ways that motivate [students] to study the scriptures diligently, to apply what they learn and to share what they are learning with others.”[6]

In Alma 37, the prophet Alma is teaching his son Helaman the significance of the records that he is about to receive, keep, and add to. Alma adds a chiasmic warning to his son Helaman and, in a sense, to all keepers of the records, Seminary and Institute instructors included. The pattern is as follows:

v. 13 “O remember, remember, my son Helaman, how strict are the commandments of God.”

v. 14 God “will keep and preserve [these records] for a wise purpose in him, that he may show forth his power unto future generations.”

v. 16 “Do with these things which are sacred according to that which the Lord doth command you.”

v. 18 God “will preserve these things for a wise purpose in him, that he might show forth his power unto future generations.”

v. 20 “I command you my son Helaman, that ye be diligent in fulfilling all my words, and that ye be diligent in keeping the commandments of God.”

The center of this pattern, and the point of the chiasmus, is that we must do with the scriptures what God would have us do. And what does the Lord want Seminary and Institute instructors to do with his words? The Gospel and Teaching Learning Handbook is filled with instructions on how to use the scriptures. An important instruction is “there are few things teachers can do that will have a more powerful and long-lasting influence for good in the lives of their students than helping them learn to love the scriptures and to study them on a daily basis. This often begins as teachers set an example of daily scripture study in their own lives. Engaging in meaningful, personal scripture study every day qualifies teachers to offer personal testimony to their students of the value of the scriptures in their own lives. Such testimony can be an important catalyst in helping students commit to studying the scriptures regularly on their own.”[7]

The recent change to the curriculum, causing a blend between topical and sequential scripture teaching and aligning it with Come, Follow Me methods, will also lend to a deepened love for the scriptures. In a discussion with Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, Sister Bonnie H. Cordon, and Brother Chad H Webb, Elder Kim B. Clark stated that students “need to have personal spiritual experiences with the scriptures.” Chad Webb expressed that the alignment will “help them still love the scriptures and be tied to what the scriptures teach, but in a way that’s relevant to them and . . . of most worth at this time in their life.”[8]

When students see how we treat the scriptures and sense our deep love, respect, and reverence for the word of God and the living prophets, they will be nourished as we teach and as they study on their own. They will, like others who had perfect understanding, shake “the very powers of hell” (Alma 48:13) and “wax stronger and stronger in their humility, and firmer and firmer in the faith of Christ, unto the filling their souls with joy and consolation, yea, even to the purifying and the sanctification of their hearts, which sanctification cometh because of their yielding their hearts unto God” (Helaman 3:35).

Clothing Youth

In Doctrine and Covenants 88, the Lord is instructing the Saints on how to establish the school of the prophets. This historic, seminary-like classroom environment was set up by the Lord through a list of commandments, things they should do and things they should not do (see Doctrine and Covenants 88:117–124). After listing these commands, the Lord says, “Above all things, clothe yourselves with the bond of charity” (Doctrine and Covenants 88:125). This idea of “putting on” charity—on ourselves and others—is fitting for a seminary classroom. Chad Webb has taught:

Many students come from difficult, even traumatic situations that leave them doubting if they are loved and valued. Some struggle with challenges, with anxiety, or with perfectionism that causes them to hear condemnation instead of hope. Others feel unwanted because they face temptations or challenges in relation to sexual identity and feel trapped and worried that they have no place or future in the restored Church of Jesus Christ.

As teachers, we need to seek to understand what these experiences may be like for our students. . . .

Whatever personal challenges students may face, we need to listen in order to understand and to communicate sincere empathy and love. We need to create classrooms where questions are welcomed, and issues are discussed with respect and thoughtfulness. We need to clearly teach truth and help every student recognize his or her eternal identity as children of loving heavenly parents. And we need to help students know they’re not alone. Showing them more love and understanding will invite the Holy Ghost, increase learning, and heal broken hearts.[9]

The Gospel Teaching and Learning handbook has ideas for how to show love for students: learning students’ names and more about them—including the talents and abilities of disabled students, praying for students, welcoming students to class, allowing students to participate, listening to students, and attending events where students are participating.[10] By leading out with love, we create an expectation for students that they must love each other.

Students need to understand that they are not only in class for themselves, but for each other student in their class as well. A sincere testimony, an honest question, and thoughtful comment can lift a burden, grant peace and lead to conversion. Having that kind of spiritual experience with other students will only encourage more of the same from other students.

Brother Russell T. Osguthorpe, former Sunday School General President (2009–14), shared a story in which a sister from Oaxaca, Mexico, was teaching a youth Sunday School class. She was teaching about the doctrine of eternal families, and she asked the students to share their own experiences with this doctrine. Amid expressions of gratitude for blessings of family, one young man, seated in the back said, “I don’t want a family like mine. My dad is alcoholic and is drunk every morning when I wake up.” The teacher followed this thought up with a question about what the young man will need to do to ensure that he does have an eternal family. The young man expressed that he needed to have good friends. Brother Osguthorpe observed what happened next:

The young man sitting next to him put his hand on his shoulder to show support, and then the young man sitting on the other side did the same. The teacher then asked the class, ‘If you hope to have an eternal family, what will you need to do right now to plan for it?’ The class members shared their ideas. Then the teacher asked, “Do you think you might write your plan down and bring it next week so that we can talk about it?” They agreed.

I am certain that this teacher, as she prepared to teach, thought deeply about how she would invite participation and how she would invite learners to live the principle she was teaching. She was not concerned about delivering content to her learners. She was concerned about helping them deepen their own conversion.

This teacher invited all to participate. All were not “spokesmen at once,” but each one shared in turn. And all were edified of all. I was edified by the power of the comments and testimonies of class members. The teacher had created an environment of trust and acceptance. The Spirit was evident throughout the class. The teacher, as well as the students, were all trying to help each other by building one another up. This was how the Savior taught.[11]

According to the Gospel Teaching and Learning handbook, “When students know they are loved and respected by their teacher and other students, they are more likely to come to class ready to learn. The acceptance and love they feel from others can soften their hearts, reduce fear, and engender within them the desire and confidence necessary to share their experiences and feelings with their teacher and other class members.”[12]

Giving Youth a Place

As when the Nephites gave the people of Ammon a land for their inheritance, the former refugees gave the Zoramites places for their inheritance. Surely this meant cutting into their own lands and perhaps even diminishing their own farms, but having once been homeless, lotless, and farmless, these people cheerfully gave to their neighbors.

The Savior did not have “a place” made for him during his mortal ministry. “Foxes have holes,” he said, “and birds of the air have nests; but the Son of man hath not where to lay his head” (Luke 9:58). Although there may not have been a physical place for the Redeemer of the world, he promised his disciples, “In my Father’s house are many mansions: if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you” (John 14:2). Making a place for others is a Christlike attribute. There was always room at his table for publicans and sinners (see Matthew 9:9–10; 10:3; 21:31–32; Mark 2:14–15; Luke 3:12; 5:27–29; 7:29; 15:1; 18:13; 19:2, 8).

In a Marjorie Pay Hinckley lecture, Dr. Erik Carter of Vanderbilt University discussed how to create a sense of belonging for those with disabilities. In this lecture he said, “Even though I am going to focus on those young people [with disabilities], . . . this is really a conversation tonight about what it means to foster belonging for anyone. So I challenge you to think about how the ideas I share today might be expressed within the communities that matter most to each of you.”[13]

For Seminaries and Institutes personnel, a community that matters is our classroom—its climate and its youth. In this lecture, Dr. Carter gives ten things people need to be to ensure that they feel like they have “a place.” They are as follows:

1. To be present

2. To be invited

3. To be welcomed

4. To be known

5. To be accepted

6. To be supported

7. To be cared for

8. To be befriended

9. To be needed

10. To be loved

A teacher may apply these ten methods into their classrooms in a variety of ways, but all students need to feel these things from us. Dr. Carter taught, “Uncertainty almost always leads to avoidance. . . . And when people go unacknowledged or overlooked or ignored, they stop coming eventually.”

The article went on to say, “Small acts such as greeting new families [or students] when they arrive, introducing them to others, drawing them into conversations, inviting them to other church events, involving them in smaller groups, noticing absences, and following up to know why they are gone are simple ways to reach out that are very effective.”[14]

Giving our students a place does not simply mean having an open desk for them, it means having an open heart to them. No matter who the students are—with their histories, their disabilities, or their problems—there needs to be a place for them. A place must be made for even those who may not love the gospel, scripture study, or the Savior as much as we do. The Savior taught, “For if ye love them which love you, what reward have ye?” (Matthew 5:46). When the Zoramite and Lamanite refugees came to Jershon, surely there was a steep learning curve for becoming part of their culture. But we never read of refugees fleeing the land of Jershon. Through the cycle of nourishing, clothing, giving a place, and administering, refugees came and they stayed.

Administering to Youth

Sister Lori Newbold taught a great lesson about how to administer to the youth in our classroom. She taught Seminaries and Institutes faculty, “Our hope is that each of us will develop or deepen the Christlike ability to see beyond labels and outward appearances and learn to see each student as a unique individual with divine potential and treat him or her accordingly.”[15]

God’s children are individual and singular. They are unique in circumstance, thought, feeling, personality, character, and spirit. They encapsulate a “one.” The youth who sit in our classrooms are spending their days being saturated in a society that clouds their identity by trying to give them so many other ones. They might be labeled “smart,” “dumb,” “class clown,” “ugly,” “popular”—anything but children of the Most High God. Seminaries and institutes should be places where youth can remove all other labels and see themselves for who they are. But, for that to happen, we as teachers must also avoid similar labels, and not see students simply as “troubled,” “late,” “difficult,” “uninterested,” “apathetic,” “disconnected,” “loud”—we must also continue to see them as the Lord does; as “one” child of God who deserves our best, and every ounce of love the Savior has to offer.

A wonderful example of this in scripture is the parable of the good Samaritan. The Samaritan, when he noticed the injured man, “came where he was: and when he saw him, he had compassion on him, and went to him” (Luke 10:33–34).

What does it mean to see with compassion? What does it look like when a teacher sees the youth this way? Notice that the teacher that sees with compassion isn’t afraid to go to the student, go to where the student is, and begin with where they are. President Brigham Young has taught, “I wish to urge upon the Saints . . . to understand men and women as they are, and not understand them as you are.”[16]

After the Samaritan sees and goes to the man, he goes through a process to ensure that this man is taken care of. We see him bind wounds, pour in oil, put the man on his own beast, take him to an inn, and then ensure a follow-up with the innkeeper (see Luke 10:34–35). This same process can be offered by seminary and institute teachers by doing the following things:

Bind Wounds

Wounds are healed as we teach students the word of God as found in the scriptures and words of the prophets. The Savior’s power is in his word, and we open ourselves up to that healing as we immerse ourselves in a study of his words.

Pour in Oil

The oil most likely would have been olive oil, and the comparison to the Atonement of Jesus Christ performed in Gethsemane cannot be ignored. As we make Christ central to our teaching, we help students rely on His Atonement.

Put Them on a Beast

We might have to go above and beyond the forty-hour work week to administer effectively to our students. Some teachers may see this as burdening the beast, but when we remember a soul “is great in the sight of God” (Doctrine and Covenants 18:10), it will seem less of a sacrifice.

Take Them to an Inn

There are many places where youth can receive the help they need, and none is more important than their own ward and stake, where leaders are equipped with priesthood keys to ensure their spiritual safety and rest.

Follow Up

We are not to be dump trucks, dropping these youth off at their bishops’ feet. Instead we are to work with them, including following up with their efforts to help these youth. When we see students as the Samaritan and the Savior did, carefully and with their true potential in mind, we can administer to them in a way that will promote healing, help, and holiness in their lives. We truly will administer to them according to their wants (see Alma 35:9).

Conclusion

What was the effect of the people of Ammon in the land of Jershon taking care of refugees? It produced some of the greatest youth the Book of Mormon had ever seen, the stripling warriors. They came to aid the Nephite armies in a great time of need. They were described as “young,” “exceedingly valiant for courage, . . . strength and activity,” and “true at all times, . . . for they had been taught to keep the commandments of God and to walk uprightly before him” (Alma 53:20–21). In the heat of battle, which our youth face daily, they were described as fighting “as if with the strength of God” (Alma 56:56). “They did obey and observe to perform every word of command with exactness; yea, and even according to their faith it was done unto them;” they had “exceeding faith in that which they had been taught to believe—that there was a just God, and whosoever did not doubt, that they should be preserved by his marvelous power. . . . Their minds are firm, and they do put their trust in God continually” (Alma 57:21, 26–27). These are the kinds of youth the Lord needs in these latter days. This is what lies inside of each of our students and our potential students. Elder Neil L. Andersen has observed that these youth “are some of the most spiritually sensitive sons and daughters of God that have ever entered mortality.”[17]

Seminaries and institutes are tools for the gathering of Israel, and they are best used alongside priesthood keys to seek out spiritual refugees who are “only kept from the truth because they know not where to find it” (Doctrine and Covenants 123:12). In addition to those efforts, we can “nourish,” “clothe,” “give place,” and “administer” to our students. Thus, our classrooms become like the land of Jershon, where spiritual refugees will come for safety, for the Spirit, and greatest of all, for the Savior.

Notes

[1] James Emery White, in Michael Dimock, “Defining Generations: Where Millennials End and Generation Z Begins,” Pew Research Center, 17 January 2019, as quoted by Jeffrey R. Holland, “Angels and Astonishment” (Seminaries and Institutes training broadcast, June 2019), 3.

[2] Randall L. Hall, Kim B. Clark, Elaine S. Dalton, and Richard I. Heaton, “Teaching and Learning Panel” (Seminaries and Institutes broadcast, August 2009).

[3] Ronald A. Rasband, “Jesus Christ Is the Answer” (Evening with a General Authority, 8 February 2019), 2.

[4] Jeffrey R. Holland, “A Teacher Come from God,” Ensign, May 1998, 3–4.

[5] Kim B. Clark, “Deep Learning and Joy in the Lord” (Seminaries and Institutes of Religion Annual Training Broadcast, 13 June 2017), 4.

[6] Church Educational System, Gospel Teaching and Learning (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2012), 2.2.1.

[7] Church Educational System, Gospel Teaching and Learning, 2.3.1.

[8] As quoted in Aubrey Eyre, “Seminaries to Align with Come, Follow Me Curriculum and Schedule in 2020,” Church News, 31 March 2019, 4–5.

[9] Chad H Webb, “Above All Things” (Seminaries and Institutes of Religion Annual Training Broadcast, June 2019), 4–5.

[10] See Church Educational System, Gospel Teaching and Learning, 2.2.1.

[11] Russell T. Osguthorpe, “Come, Follow Me,” Church News, 28 December 2013, 5.

[12] Church Educational System, Gospel Teaching and Learning, 2.2.1.

[13] Erik Carter, as quoted in Marianne Holman Prescott, “10 Ways to Help Those with Disabilities Feel a Sense of Belonging,” Church News, 16 February 2018, 11.

[14] Carter, as quoted in Prescott, “10 Ways to Help,” 11.

[15] Lori Newbold, “See the One,” Religious Educator 19, no. 3 (2018): 49–55.

[16] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 8:37.

[17] Neil L. Andersen, “A Classroom of Faith, Hope, and Charity,” Religious Educator 15, no. 3 (2014): 16.