John Hilton III, "The Isaiah Map: An Approach to Teaching Isaiah," Religious Educator 21, no. 1 (2020): 55–73.

John Hilton III (john_hiltoniii@byu.edu) was an associate professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this was written.

The main goal of the Isaiah Map is to help students to be able to study Isaiah passages on their own.

The main goal of the Isaiah Map is to help students to be able to study Isaiah passages on their own.

Isaiah is an extremely important prophet—his words were endorsed by the Savior himself (see 3 Nephi 23:1). Because Isaiah’s words can be difficult to comprehend, religious educators have a significant responsibility to help their students understand them. Perhaps the best opportunity to teach Isaiah in a Sunday School, seminary, or institute setting is during a course in the Old Testament. The next best opportunity is when teaching the Book of Mormon. “Nineteen of Isaiah’s sixty-six chapters are quoted in their entirety in the Book of Mormon and, except for two verses, two other chapters are completely quoted. Of the 1,292 verses in Isaiah, about 430 are quoted in the Book of Mormon, some of them more than once (for a total of nearly 600). If all of the quotations from Isaiah in the Book of Mormon were moved into one place and called the book of Isaiah, it would constitute the fourth largest book in the Book of Mormon.”[1] Nephi clearly made Isaiah an integral part of his two books. In fact, Joseph M. Spencer has argued that Nephi worked “to ensure that his readers would give their most sustained and dedicated study to the ‘Isaiah chapters.’ There is, then, an unavoidable irony about the way Isaiah is usually handled by Book of Mormon readers—that is, as a barrier.”[2]

Some teachers may not feel confident in their knowledge of Isaiah and therefore shy away from teaching these chapters. I confess that earlier in my career I would get through the Isaiah chapters as quickly as possible and often avoid the actual text of Isaiah. For example, when teaching 2 Nephi 6–10, I might briefly mention an Isaiah passage or two and then focus my time and attention on 2 Nephi 9. But because Nephi, Jacob, and other Book of Mormon prophets intently focus on Isaiah, religious educators should view helping students comprehend Isaiah’s words as one of their major objectives, both when teaching the Old Testament and the Book of Mormon. Most students can understand Genesis 39, 1 Nephi 8, or other such chapters on their own, but many need help with Isaiah 48–49 (1 Nephi 20–21).

Nephi testified that the words of Isaiah would be “of great worth unto them in the last days; for in that day shall they understand them” (2 Nephi 25:8). We live in the latter days, and if we take Nephi at his word, we can understand Isaiah. The purpose of this article is to share a teaching methodology that helps students comprehend Isaiah and significantly increase their confidence in understanding his words. This approach focuses on understanding the geography and historical context of Isaiah’s day and the following generations as suggested by Nephi (see 2 Nephi 25:6). I do not argue that this is the only or even best way to understand Isaiah; however, I have found that this background information helps students to become confident they can understand Isaiah. I view this approach as one important anchor from which students can then begin their exploration of Isaiah. In this article I first outline general background knowledge that aids student understanding, and I then explain an approach on how to help students retain this knowledge.[3] Afterward, I provide some examples of how I might use this background knowledge when teaching specific sections of Isaiah.

At the heart of this approach is walking students through a one-page map that covers key locations, countries, people, and dates important to understanding Isaiah. Although some students know discrete events (e.g., the ten tribes were scattered), for most, their ability to connect and relate multiple events during 730 BC and 530 BC is relatively weak. By drawing this information on one piece of paper, students can create something they can easily grasp and reference. Before beginning a study of Isaiah (either in an Old Testament or Book of Mormon class), I will spend at least twenty to thirty minutes sharing the below background information with them. I first present what I call the “Isaiah Map” holistically and then walk through its constituent parts.[4] In an attempt to have smoother prose, I will write as though I were giving directions to other teachers; however, what follows are simply suggestions and should be understood as such.

The Isaiah Map: Helping Students Understand Isaiah

We begin by displaying the Isaiah Map. While this may seem like a lot of information all at once, it provides a helpful overview of the information students will learn. We can explain each part of the map one piece at a time and help them see its relevance for understanding Isaiah, beginning with the top left-hand corner. To help students own this information, I invite them to draw a copy of the map on their own paper as I draw it on the board. Although handouts are helpful, students will learn the information better if they draw the map (including all the information it contains). I draw it with the students one step at a time, as outlined below.

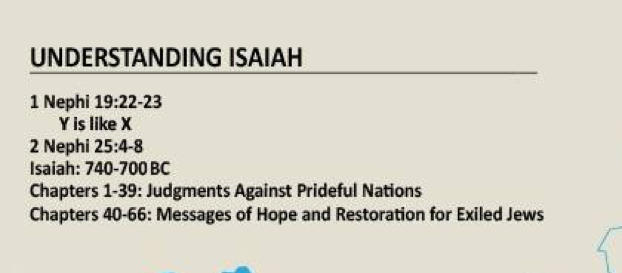

In 1 Nephi 19:22–23, Nephi states, “I, Nephi, . . . did read many things to them, which were engraven upon the plates of brass, that they might know concerning the doings of the Lord in other lands, among people of old. . . . I did read unto them that which was written by the prophet Isaiah; for I did liken all scriptures unto us, that it might be for our profit and learning.” Note that Nephi prefaces his quotation of Isaiah by saying that it is about “people of old” in other lands. Although Isaiah can be likened to our day, we should not be surprised to learn that many of his writings pertained to the people of his day.

While what it means to liken the scriptures has been debated,[5] I define likening as the process of saying “y is like x.” When studying Isaiah (and other scripture), we perhaps too frequently focus on the y, the application, before understanding the x. In this case, the x is the historical events about which Isaiah prophesied. Jumping straight to the y can be extremely detrimental to our understanding of Isaiah. Consider the following experience that a returned missionary candidly shared with me:

I honestly had difficulty understanding Isaiah and would sometimes just pick out phrases that stood out to me. One of these is found in 2 Nephi 18:9: “Associate yourselves.” I thought this was a good phrase, and it reminded me of the importance of being social and reaching out to others. I later realized, however, that I had taken the verse out of context. The full phrase is “Associate yourselves, O ye people, and ye shall be broken in pieces.” When I understood the historical context of this chapter, I realized that Isaiah’s messages had been exactly the opposite of what I had determined it to be. By trying to make it easy to liken Isaiah to modern life, I had missed the key elements of what Isaiah was really teaching.

As this experience demonstrates, it is easy to pull Isaiah’s words out of context. Students’ ability to liken will be dramatically increased as they understand the x, the historical context of Isaiah’s words.

The second passage of scripture to share with students is 2 Nephi 25:6. After extensively quoting from Isaiah, Nephi provides important keys[6] for understanding Isaiah: “I . . . have dwelt at Jerusalem, wherefore I know concerning the regions round about; and I have made mention unto my children concerning the judgments of God, which hath come to pass among the Jews, unto my children, according to all that which Isaiah hath spoken” (2 Nephi 25:6). It is clear from Nephi’s words that understanding both the “regions round about” (geography) and “judgments of God” (possibly a reference to contemporary history) are essential to understanding Isaiah.

Students can see the importance of knowing geography and contemporary history by trying to interpret the following sentence: “Trump is going to the Big Apple to meet with the UN. He is angry at Beijing.” Most students can understand this hypothetical statement. But would a person living 2,500 years from now understand it? This statement, written in the sociological lexicon of our time, could be very confusing to people not familiar with the geography and politics of the early twenty-first century. Similarly, helping students understand the history and geography of Isaiah’s time will allow them to better understand Isaiah’s words.

After reviewing these two passages, provide students with some simple facts about Isaiah and his book. First, Isaiah prophesied around 740–700 BC. This information allows us to connect with the contemporary events of Isaiah’s lifetime. Tell students that Isaiah can be seen as having at least two major divisions. Depending on the context of the class, you may want to provide more in-depth information about authorship issues in Isaiah and why they are important in relation to the Book of Mormon.[7] The two main themes I put on the map (and I acknowledge that this is a gross simplification) are, first, “Judgments against prideful nations” (Isaiah 1–39). Second, in Isaiah 40–66, there is a consistent theme of “Messages of hope and restoration for exiled Jews.”[8]

Having discussed the upper left-hand corner of the map, we turn to the rest of the information on the left-hand portion of the map.

Because Nephi specifically said that he knew concerning “the regions round about,” students should also learn a few geographical reference points. In addition to bodies of water, students can place four different countries on the map. Some students may have forgotten that after King Solomon’s reign, Israel was divided in two kingdoms, often referred to as Israel (the Northern Kingdom) and Judah (the Southern Kingdom; see 1 Kings 12). The map provides three facts about these two kingdoms. First, Judah’s capital city was Jerusalem (also referred to as Zion), second, its principle tribe was Judah, and third, it had a series of Davidic kings. Its two most important kings during Isaiah’s lifetime were Ahaz and Hezekiah. To the north was the kingdom of Israel, which primarily consisted of the land originally designated for ten of the tribes of Israel. Three important facts for students to remember are first, the capital of Israel was Samaria; second, the dominant tribe was Ephraim; and third, one of its kings in Isaiah’s time was Pekah, the son of Remaliah.

Briefly mention that students should know a little about Syria, such as that Damascus was its capital and Rezin was its king. Students also illustrate some trees on their map to remind themselves that Lebanon was known for its cedar forests. While students may feel overloaded with this information, many will be excited as they can sense that it will help them better understand Isaiah. Tell students that Isaiah writes explicitly about Ahaz, Pekah, and Rezin. Knowing their names will help students understand the context of Isaiah’s message (more detailed information regarding the Syro-Ephraimite War will be provided later in this article). Because Isaiah refers to kingdoms by their dominant tribe or capital city, this information is important to know as well. This was living history for Isaiah and recent history for Nephi; students of Isaiah should understand it just as students of American history should know relevant names and places.

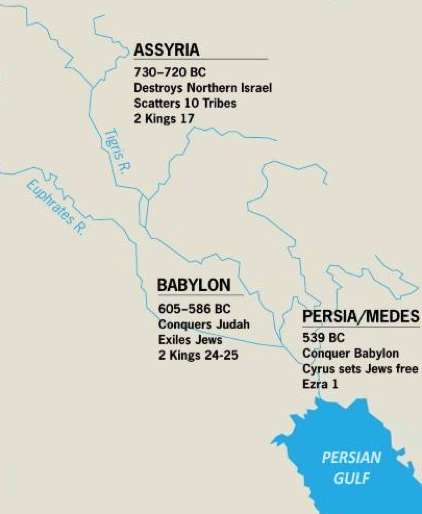

Finally, focus on the right-hand portion of the map by providing students with a two-minute summary of two hundred years of ancient Near Eastern history (roughly 730–530 BC). This section is relatively easy to grasp because there is a clear narrative storyline.[9]

Point out the Persian Gulf along with the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers and tell students that Isaiah will refer to the Euphrates in his prophecies. Students should know that between 730 and 530 BC, there were three major superpowers. The first was Assyria, who in the 730s–720s BC destroyed the kingdom of Israel and carried away its inhabitants as described in 2 Kings 17. Remembering the information in the upper left-hand corner of the map helps students see that Assyria’s conquering of Israel takes place during Isaiah’s ministry. Because part of the literal scattering of Israel happens during Isaiah’s lifetime, we should not be surprised that this is an important theme in his ministry.

Although Assyria attacked the Southern Kingdom (circa 701 BC), it did not defeat Jerusalem. However, in approximately 625 BC, Babylon, a new superpower, defeated Assyria and between 605 and 586 BC made multiple incursions into the Southern Kingdom, eventually resulting in the destruction of Jerusalem (see 2 Kings 24–25). Babylon then carried the Jews into exile. Note that while the inhabitants of the Northern Kingdom were scattered and lost to history, those in the Southern Kingdom (primarily from Judah) continued to maintain their religious identity during this time of exile.

The third and final superpower on the map is Persia. In 539 BC, Cyrus, the king of Persia, defeated Babylon and allowed the Jews to return to their homeland if they chose (see Ezra 1).[10] Emphasize to students that the scripture references are important so that they can go back and verify that the events we are discussing are in fact scriptural and part of an overall narrative with which they should be familiar. Help students understand that the map they have drawn is a simple summary of some important biblical chapters.

Song Lyrics and Multiple Meanings

Typically, I share the foregoing information in the last twenty minutes of the class period before beginning our study of Isaiah. The following day, when beginning a study of Isaiah (either Isaiah 1 or 1 Nephi 20–22), we review all of this information a second time, and I invite students to again draw the map. This repetition is a vital part of helping students understand this material well enough to use it to interpret Isaiah.[11] Before pressing forward with students into the actual text of Isaiah, consider sharing with them two additional points. First, invite students to analyze popular song lyrics. The following are a little dated, but suitable contemporary songs could be substituted:

If you ain’t here, I just can’t breathe

It’s no air, no air, no air, air, no air, air

I walked, I ran, I jumped, I flew

Right off the ground to float to you

There’s no gravity to hold me down for real.[12]

We could joke that perhaps 2,500 years from now people might analyze these words in a class and say something like, “During this time period there was an environmental crisis, such that people became very concerned about a lack of oxygen. Some even speculated that global warming would lead to the eradication of gravity.” Of course, that is not the meaning of the lyrics—one needs to read between the lines and grasp the overall message. In this case, the author is in love with another person and uses the idea of not being able to breathe and floating to express this thought. Similarly, Isaiah often writes poetically. When we read that “kings . . . and their queens . . . shall . . . lick up the dust of thy feet” (Isaiah 49:23), we don’t need to ask ourselves which kings or queens licked the feet of which ancient person; rather, we can grasp that one general meaning Isaiah is describing is how gentile rulers will serve the people of Judah.[13]

Second, share with students the following quotation from President Dallin H. Oaks: “The book of Isaiah contains numerous prophecies that seem to have multiple fulfillments. One seems to involve the people of Isaiah’s day or the circumstances of the next generation. Another meaning, often symbolic, seems to refer to events in the meridian of time, when Jerusalem was destroyed and her people scattered after the crucifixion of the Son of God. Still another meaning or fulfillment of the same prophecy seems to relate to the events attending the Second Coming of the Savior.”[14] Thus, we will likely find multiple correct answers to the question, “What did Isaiah mean in this passage?” To best liken Isaiah’s words to ourselves, it is helpful to understand what they might have meant during Isaiah’s lifetime and for the generation that followed (making sure we understand the x). In the next section I provide some specific examples of how teachers can help students connect Isaiah’s words with the events on the map that they have learned.

Sample Passages

How can historical context help students understand Isaiah? In this section, I examine three specific passages.[15]

1 Nephi 20–21 (Isaiah 48–49)

Begin by reminding students that a frequent topic in Isaiah chapters 40–66 is “messages of hope for exiled Jews.” Point out that 1 Nephi 20:1–2 states, “Hearken and hear this, O house of Jacob, who . . . come forth out of the waters of Judah . . . [and] call themselves of the holy city.” “Judah” and “the holy City” (Jerusalem) remind us of the Southern Kingdom. Verse 20 adds additional context: “Go ye forth of Babylon. . . .” In other words, one interpretation of this chapter is that it is directed to exiled Jews as a hopeful message that they will be able to escape Babylonian captivity.

Many passages in these chapters are easy to understand when we have this basic framework. For example, we read, “Behold, I have refined thee, I have chosen thee in the furnace of affliction” (1 Nephi 20:10). What is the affliction? One affliction is that Babylon destroyed Jerusalem. To exiled Jews, God’s message could be, “Though I am refining you, I’m not going to cut you off.”

The Lord tells the people, “I am the first, and I am also the last. Mine hand hath also laid the foundation of the earth, and my right hand hath spanned the heavens” (1 Nephi 20:12–13). In other words, the Lord says, “I am everything. I am all-powerful, and I will help you.” This is clearly a message of hope. We next read, “The Lord . . . will fulfil his word which he hath declared by them; and he will do his pleasure on Babylon” (1 Nephi 20:14). Thus, he reminds the people of the promises he has made and his commitment to destroy Babylon.

From historical context, we know how the Lord will deliver the Jews. Persia will eventually overtake Babylon and Cyrus the king of Persia will allow Jerusalem to be rebuilt. Isaiah uses language that reminds readers of the exodus out of Egypt to offer them hope: “Go ye forth of Babylon, flee ye from the Chaldeans, with a voice of singing declare ye, tell this, utter to the end of the earth; say ye: The Lord hath redeemed his servant Jacob. And they thirsted not; he led them through the deserts; he caused the waters to flow out of the rock for them; he clave the rock also and the waters gushed out” (1 Nephi 20:20–21). Just as God brought the Israelites out of Egypt into the promised land, he will deliver them from the Babylonians.[16]

This same message of hope continues in 1 Nephi 21. We read, “Thus saith the Lord, the Redeemer of Israel, his Holy One, to him whom man despiseth, to him whom the nations abhorreth, to servants of rulers: Kings shall see and arise, princes also shall worship, because of the Lord that is faithful” (1 Nephi 21:7). One way to understand the message in this context is that “him whom the nations abhorreth” is the Southern Kingdom that was destroyed by Babylon. Now, hope is on the horizon. The Lord is faithful, and new kings will arrive (namely, Cyrus) to help restore Jerusalem.

The message of hope continues. “Zion hath said: The Lord hath forsaken me, and my Lord hath forgotten me—but he will show that he hath not. For can a woman forget her sucking child, that she should not have compassion on the son of her womb? Yea, they may forget, yet will I not forget thee, O house of Israel. Behold, I have graven thee upon the palms of my hands; thy walls are continually before me” (1 Nephi 21:14–16). Although Babylon destroyed the walls that surround Jerusalem, causing the people to think God had forgotten them, God remembers them.

At the end of chapter 21 the Lord extends a powerful message: “Behold, I will lift up mine hand to the Gentiles, and set up my standard to the people; and they shall bring thy sons in their arms, and thy daughters shall be carried upon their shoulders” (1 Nephi 21:22). In this particular context, one group of Gentiles who are going to lift up the sons and daughters of the Jews in exile can be understood to be the Persians, who provided support for the Jews’ return to Jerusalem.

We next read, “Kings shall be thy nursing fathers, and their queens thy nursing mothers; they shall bow down to thee with their face towards the earth, and lick up the dust of thy feet; and thou shalt know that I am the Lord; for they shall not be ashamed that wait for me. For shall the prey be taken from the mighty, or the lawful captives delivered? But thus saith the Lord, even the captives of the mighty shall be taken away, and the prey of the terrible shall be delivered” (1 Nephi 21:23–25).

Usually one does not steal prey from the mighty, but following the interpretation given above, the prey could be understood to be the Southern Kingdom that will be delivered from Babylon through Persia, represented as nursing fathers and mothers. “And I will feed them [Babylon] that oppress thee [kingdom of Judah] with their own flesh; they shall be drunken with their own blood as with sweet wine” (1 Nephi 21:26). Although gruesome, this is a message of hope for exiled Jews because it represents Babylon’s thorough destruction.

This interpretation can help students liken the context of this passage to their lives. The Jews felt that they had been forgotten—and perhaps rightfully so. They were experiencing a multigenerational trial. While students face various difficulties, most have never had a trial that’s lasted for seventy years (the length of Judah’s exile in Babylon). Some may have had a trial that lasted seventy months, seventy weeks, or seventy days (that’s less than two transfers with a difficult mission companion!), but some of us get concerned if we have a trial that lasts more than seventy hours. Thus the message that the Lord has not forgotten his covenant people is an impressive call to hope. He did not forget the Jews in exile, and he will not forget us, although his help may not always come in the timeframe we desire. Another way to understand this passage is that just as the Jews faced the oppression of Babylon, we face the challenges of sin and death. But just as God helped the Jews, so also the Atonement of Jesus Christ helps us conquer these seemingly invincible foes. Understanding the historical context of this passages adds greater depth to our understanding of the delivering power of the Atonement (see 2 Nephi 9:25–26).

2 Nephi 17–18 (Isaiah 7–8)

The context of 2 Nephi 17 is what is commonly referred to as the Syro-Ephraimite War. Assyria planned to dominate the entire Middle East and beyond. As Jason Combs noted, “In an effort to staunch the rising tide of Assyrian aggression or to expand their own territorial control, Rezin, king of Syria, attempted to form a coalition of those kingdoms that had been subjugated by Assyria,”[17] which countries included Israel and Judah. Syria and Israel were preparing to go to war against Judah to enforce Judah’s cooperation in the fight against Assyria. The beginning verses of these chapters take place with this historical backdrop.[18] I include them below with explanatory notations in brackets.

And it came to pass in the days of Ahaz the son of Jotham, the son of Uzziah, king of Judah, that Rezin, king of Syria, and Pekah the son of Remaliah, king of Israel, went up toward Jerusalem to war against it, but could not prevail against it. [Students should be able to connect these names with what they have drawn on the map and thus recognize that Syria and Israel were at odds with Judah.]

And it was told the house of David, saying: Syria is confederate with Ephraim. And his heart was moved, and the heart of his people, as the trees of the wood are moved with the wind. [The people in the Southern Kingdom learn of the plan described in verse 1 and are afraid.]

Then said the Lord unto Isaiah: Go forth now to meet Ahaz, thou, and Shear-jashub thy son, at the end of the conduit of the upper pool in the highway of the fuller’s field; [The Lord tells Isaiah to go with his son and meet Ahaz, king of the Southern Kingdom.]

And say unto him, Take heed, and be quiet; fear not, neither be faint-hearted for the two tails of these smoking firebrands, for the fierce anger of Rezin with Syria, and of the son of Remaliah. [Isaiah was to tell Ahaz not to be afraid of these two kingdoms (the Northern Kingdom of Israel and Syria).]

Because Syria, Ephraim, and the son of Remaliah, have taken evil counsel against thee, saying:

Let us go up against Judah, and vex it, and let us make a breach therein for us, and set a king in the midst of it, even the son of Tabeal [Syria and the Northern Kingdom plan to install a puppet king in Judah who will join them in their fight against Assyria]:

Thus saith the Lord God: It shall not stand, neither shall it come to pass. [Even though there is a plot against you by Syria and Israel to replace you as king, don’t worry about it, it’s not going to happen.]

For the head of Syria is Damascus, and the head of Damascus is Rezin; and within threescore and five years shall Ephraim be broken, that it be not a people. [Isaiah concludes, “The Lord is going to take care of Syria and the Northern Kingdom; you do not have to worry about them.”] (2 Nephi 17:1–8)

Thus in context, Isaiah has told Ahaz not to worry about this potential attack. Next we read, “The Lord spake again unto Ahaz, saying, Ask thee a sign of the Lord thy God; ask it either in the depths, or in the heights above. But Ahaz said, I will not ask, neither will I tempt the Lord” (2 Nephi 17:10–12). Students might be inclined to think that Ahaz is acting righteously by not seeking a sign; however, Ahaz’s response actually appears to be false piety. Context suggests that Ahaz was a wicked king (see 2 Kings 16:2) and that Ahaz simply didn’t want to receive advice from the Lord.

Although Ahaz did not want a sign, Isaiah told him a sign would nevertheless be given: “Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel” (2 Nephi 17:14). Students likely will immediately identify this passage with the birth of Christ because of its familiar quotation in Matthew 1:23. While this passage certainly is connected with the Savior’s birth, we can help our students see that Ahaz is worried about an imminent invasion—how would the birth of a Savior in more than seven hundred years be a sign for him? Particularly when we note the end of verse 16: “For before the child shall know to refuse the evil, and choose the good, the land that thou [Ahaz] abhorrest shall be forsaken of both her kings” (2 Nephi 17:16). In other words, Ahaz’s enemies (Israel and Syria) will be destroyed before this child that Isaiah speaks of is old enough to know right from wrong.

Commenting on this passage, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland wrote, “This sign was given to the Old Testament King Ahaz, encouraging him to take his strength from the Lord rather than the military might of Damascus, Samaria, or other militant camps. . . . There are plural or parallel elements to this prophecy, as with so much of Isaiah’s writing. The most immediate meaning was probably focused on Isaiah’s wife, . . . who brought forth a son about this time [see 2 Nephi 18:1–4], the child becoming a type and shadow of the greater, later fulfillment of the prophecy that would be realized in the birth of Jesus Christ.”[19]

Isaiah gave Ahaz a stern warning: “Associate yourselves, O ye people, and ye shall be broken in pieces. . . . Take counsel together, and it shall come to naught; speak the word, and it shall not stand: for God is with us” (2 Nephi 18:9–10). Thus, Isaiah told Ahaz that he should not turn to others for help; rather, he should trust in God. Unfortunately, Ahaz did not believe Isaiah and instead turned to Assyria for assistance (see 2 Kings 16:7–8). This had serious repercussions for the Southern Kingdom of Judah in the next generation (see 2 Kings 18–19).

With a concrete understanding of the x (the historical context) of this passage, students can begin to liken these verses to themselves. Just as the Jews faced intense trials, so too do our students. They can be tempted (as was Ahaz) to turn to inappropriate sources for help and strength. Hopefully this account can fortify them to trust in Jehovah knowing that as they rely on him they will find strength and deliverance.

2 Nephi 20 (Isaiah 10)

By looking at the top left-hand corner of the map, students can see that this chapter falls in the theme of judgments of God against prideful nations. Second Nephi 20:5 helps us identify the subject of this chapter: “O Assyrian, the rod of mine anger, and the staff in their hand is their indignation.”

The Lord is talking about Assyria, which is, as students know, a major superpower during Isaiah’s lifetime. We read, “I [the Lord] will send him [the king of Assyria] against a hypocritical nation, and against the people of my wrath will I give him a charge to take the spoil, and to take the prey, and to tread them down like the mire of the streets” (2 Nephi 20:6). Because we know Assyria destroyed Israel, we can conclude Israel is the hypocritical nation. But the king of Assyria does not realize he is only an instrument in God’s hands:

Howbeit he meaneth not so, neither doth his heart think so; but in his heart it is to destroy and cut off nations not a few. For he [the king of Assyria] saith: “Are not my princes altogether kings? Is not Calno as Carchemish? Is not Hamath as Arpad? Is not Samaria as Damascus? As my hand hath founded the kingdoms of the idols, and whose graven images did excel them of Jerusalem and of Samaria; shall I not, as I have done unto Samaria and her idols, so do to Jerusalem and to her idols?” (2 Nephi 20:7–11; quotation marks added)

It’s important to remind students to carefully monitor who is speaking. This is not a passage where the Lord is condemning Jerusalem for idol worship; the principal speaker in this passage is the king of Assyria, who in essence states, “I have defeated many kingdoms. Just as I destroyed Samaria (the Northern Kingdom), I will destroy Judah (the Southern Kingdom).”[20] Students know from their map that Assyria does indeed destroy “Samaria and her idols,” but they also know that Assyria will not destroy Jerusalem (although it will destroy much of the Southern Kingdom).

An example of the pride of Assyria appears in the following passage: “For he [the king of Assyria] saith: By the strength of my hand and by my wisdom I have done these things; for I am prudent; and I have moved the borders of the people, and have robbed their treasures, and I have put down the inhabitants like a valiant man” (2 Nephi 20:13). The king of Assyria boasts that his great success has come from his power, not the Lord’s. However, the king of Assyria has been but an instrument in God’s hand. The Lord states, “Shall the ax boast itself against him that heweth therewith? Shall the saw magnify itself against him that shaketh it?” (2 Nephi 20:15). Although the king of Assyria is powerful, the Lord is in charge. Thus, the Lord states, “I will punish the fruit of the stout heart of the king of Assyria, and the glory of his high looks” (2 Nephi 20:12). Indeed, Assyria will be destroyed by Babylon and a coalition of other nations within the next century, in the time of Jeremiah and Lehi.

Once students clearly understand the context of this passage, it is easy for them to accurately liken it unto themselves. For example, many of us feel at times as though we have accomplished great things through our own abilities. When we do so, we risk falling into the same trap as the king of Assyria. Rather, we can humble ourselves and realize that we are instruments in the Lord’s hands.

Pacing and Pedagogy

To provide students with sufficient historical background, we need to allocate sufficient class time for this endeavor. While some might believe they do not have enough time to adequately teach students this background information, I believe it is a wise choice to reallocate class time from topics students can learn on their own or through other means to information they would not otherwise grasp. For example, when teaching the Book of Mormon in seminary, a teacher could include one day on each of the following: background information, 1 Nephi 20–21, 2 Nephi 6–7, and at least two days on 2 Nephi 12–24.[21]

Encourage students to be able to draw, without notes, every aspect of the Isaiah Map. Depending on the setting, teachers could work towards this end by providing students with additional practice opportunities, such as fill-in-the-blank maps, involving students in teaching material they have mastered, having students work in pairs to successfully complete maps, or administering exams in which students are tested on this material. Even in settings when grades do not count towards student GPA, many students will be motivated to do well on tests that they perceive cover valuable information.

Such exams do not even need to be graded. Educational research indicates that providing students with opportunities to repeatedly retrieve information will likely increase their retention of that information.[22] Repeated, no-stakes retrieval activities can be very effective for this purpose and using online software such as Kahoot or creating review games (such as a modified version of Jeopardy!) can be engaging for students and facilitate learning. In connection with this retrieval process, each day when I teach Isaiah chapters I either draw the map on the board or ask one or more students to do so.[23] As a result, students will have drawn the Isaiah map multiples times and be proficient in their understanding of it. This spaced-repetition also increases the likelihood that students will retain this information after they have left my classroom.[24]

The main goal of the Isaiah Map is to help students to be able to study Isaiah passages on their own. I initially walk students through Isaiah passages phrase by phrase, as a class (as illustrated in the previous section). However, once you have modeled this for students repeatedly, invite students to work in pairs during class on specific sections of Isaiah to see if they can analyze Isaiah in the same way that you have as a class. Doing this is helpful for two reasons. First, as students verbalize what they are finding in Isaiah, they sometimes realize that what seemed simple when the teacher was doing it, is difficult if they have not yet sufficiently mastered the historical context. This sharing motivates them to return to the map and pay closer attention to the explanations that are subsequently given. Second, by working together, students are often able to piece together what Isaiah is saying in his historical context. When they successfully do this on their own, their confidence in their ability to make sense of Isaiah increases. At the end of the exercise, invite a pair or two to share what they discovered, with comments from the whole class to fill in any gaps.

Conclusion

The Isaiah Map is only one approach for teaching Isaiah, and I acknowledge there are many other important facets of understanding this powerful prophet. Nephi testified that the words of Isaiah would be “of great worth unto them in the last days; for in that day shall they understand them” (2 Nephi 25:8). Perhaps one reason we can better understand Isaiah’s words in the latter days is that there has never been a time since Nephi when we know so much about the history and geography of Isaiah’s world. As we teach these basics to our students, their understanding of Isaiah will increase and they will delight in his words.

One student recently wrote me the following: “Thank you for introducing me to an understanding of Isaiah. Your method of teaching it was inspired and has led me to a deep appreciation and love of his writings. Thank you for your belief (one I now share with others) that Isaiah is meant to be understood and that it is a powerful testimony of Christ.”

Isaiah is much easier to understand when we focus on how his teachings relate to the circumstance of his day and the next generation. Naturally, as modern prophets have explained, Isaiah’s words have multiple meanings.[25] Sometimes we may focus so much on the multiple meanings that we overlook Isaiah’s historical context and thereby weaken our ability to liken his words to ourselves. As we understand Isaiah’s history and context, we will be in a stronger position to liken his words to our lives.

Notes

[1] Old Testament Seminary Teacher Resource Manual (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1998), 164. For additional background information on the importance of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon, see Dennis L. Largey, ed., Book of Mormon Reference Companion (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 340–400.

[2] Joseph M. Spencer, An Other Testament (Salem, OR: Salt Press, 2012), 53.

[3] While this historical background does not represent new scholarship, the way it is packaged helps students quickly grasp the main ideas pertaining to historical events and geography and apply them as they study Isaiah.

[4] Matthew Grey shared this approach with me; putting the map together and sharing it with students is his pedagogical innovation, which he has given permission for me to share in this article.

[5] For example, Joseph M. Spencer, An Other Testament, notes, “The word ‘liken’ is almost always equated, in commentary, to the word ‘apply’” (101). However, Spencer argues,“Likening is, for Nephi, a way of reading Isaiah, one that takes the prophet’s words to Israel as a template for making sense of Israel’s historical experience” (69). Whether likening means either, neither, or both of these things, understanding the x (the material to be likened) is vital.

[6] Note that in 2 Nephi 25:4–8, Nephi mentions other keys for understanding Isaiah. Naturally, students will benefit from their teachers assisting them in developing their abilities to utilize all of these keys. The approach described in this article focuses on those described in 2 Nephi 25:6.

[7] For an overview of biblical scholarship relating to multiple authorship in Isaiah, see Joseph Blenkinsopp, The Anchor Bible: Isaiah 1–39 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 76–92; and John N. Oswalt, The Book of Isaiah Chapters 1–39 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1986), 17–28. To keep the map simple, I do not display a potential third division within Isaiah. With respect to background considerations for Isaiah authorship and the Book of Mormon, see John W. Welch, “Authorship of the Book of Isaiah in Light of the Book of Mormon,” in Isaiah in the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: FARMS, year), 423–37. An analysis of scholarship and possibilities surrounding Isaiah authorship and the Book of Mormon is provided by Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 69–70, 291.

[8] These chapters also more broadly include all the Lord’s scattered covenant people, such as the Nephites.

[9] For additional historical background on this time period, see John N. Oswalt, The Book of Isaiah: Chapters 1–39, 4–16; Blenkinsopp, Anchor Bible: Isaiah 1–39, 98–105, and Joseph Blenkinsopp, The Anchor Bible: Isaiah 40–55 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), 98–105. While discussing this portion of the map, it may be helpful to draw arrows on the board showing the motion that takes place during this time period.

[10] Many students will not be familiar with Cyrus. It is worth explaining to them that Cyrus was considered a Gentile by Isaiah and is called the “anointed” of the Lord, which is another way of calling him a messiah (see Isaiah 44:28 and Isaiah 45:1). See also Oswalt, Isaiah Chapters 40–66, 95–102.

[11] Repeated exposures to the same material spaced across time significantly improves student retention. See J. Dunlosky et al. “Improving Students’ Learning with Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions from Cognitive and Educational Psychology,” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 14, no. 1 (2013): 4–58.

[12] Jordin Sparks, “No Air,” featuring Chris Brown, track 3 on Jordin Sparks, 2007.

[13] There are also additional ways such passages could be understood. For example, in 2 Nephi 6:12–13, Jacob applies this passage to a latter-day context.

[14] Dallin H. Oaks, “Scripture Reading and Revelation,” Ensign, January 1995, 8.

[15] In a classroom setting I would not analyze these Isaiah passages in isolation. After exploring the historical context of the passages (as done in the present study), I would also connect them with how Book of Mormon prophets utilize and liken these passages. This is beyond the scope of the present paper.

[16] For additional commentary on Isaiah 48–49 (1 Nephi 20–21), see Oswalt, Isaiah Chapters 40–66, 256–314.

[17] Jason R. Combs, “From King Ahaz’s Sign to Christ Jesus: The ‘Fulfillment’ of Isaiah 7:14,” in Prophets and Prophecies of the Old Testament, ed. Aaron Schade, Brian M. Hauglid, and Kerry Muhlestein (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 98.

[18] For additional historical background, see J. J. M. Roberts, First Isaiah: A Commentary (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2015), 109–10. Jason Combs provides extensive background and explanation of this passage in “From King Ahaz’s Sign to Christ Jesus,” 95–122.

[19] Jeffrey R. Holland, Christ and the New Covenant (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994), 79. For additional discussion on this passage and its surrounding context, see Roberts, First Isaiah, 117–20. See also Terry B. Ball, “Isaiah Chap. Review: 2 Nephi 17//

[20] For additional commentary, see Roberts, First Isaiah, 164–67.

[21] This pacing is consistent with the suggestion in the 2017 Book of Mormon seminary teacher’s manual. I emphasize it because of my own proclivity to alter it such that while I “covered” the necessary chapters, I also spent very little class time on actual Isaiah verses.

[22] See Jeffery D. Karpicke and Henry L. Roediger III, “The Critical Importance of Retrieval for Learning,” Science 319, no. 5865 (15 February 2008): 966–68..

[23] In a university setting with limited time, I will invite students to begin drawing the map as they come into class so that when teaching 2 Nephi 12–24 we can allocate more time to the actual analysis of the verses. By this point we have already drawn the map together as a class three times. Depending on your setting, you could make a game out of building it, challenging each student to add one or more elements as they come in the room, to see who can draw the map most quickly, to form teams and have each create a map on different chalkboards, and so forth.

[24] For an overview of the benefits of spaced-repetition see Nicholas J. Cepeda et al. “Distributed Practice in Verbal Recall Tasks: A Review and Quantitative Synthesis,” Psychological Bulletin 132, no. 3 (2006): 354–80.

[25] Consider what Elder Holland said about this topic: “Because [Isaiah] did freely mix and interchange material relating to his own day, to the meridian of time, and to the latter days, it is important to remember that many of Isaiah’s prophecies can be, have been, or will be fulfilled in more than one way and in more than one dispensation.” Holland, Christ and the New Covenant, 78.