Conversions, Arrests, and Friendships: A Story of Two Icelandic Police Officers

Fred E. Woods and Kári Bjarnason

Fred E. Woods and Kári Bjarnason, "'Conversions, Arrests, and Friendships: A Story of Two Icelandic Policemen," Religious Educator 20, no. 1 (2019): 138–63.

Fred E. Woods (fred_woods@byu.edu) was a professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this was written.

Kári Bjarnason (kari@vestmannaeyjar.is) was the director of the Library of Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland when this was written.

The Preaching of these missionaries and the baptisms that followed "set the whole town in an uproar."

The Preaching of these missionaries and the baptisms that followed "set the whole town in an uproar."

In 1881 in Reykjavík, Iceland, two Icelandic police officers, Þorsteinn (Thorsteinn) Jónsson and Jón Borgfirðingur, were sent to arrest Latter-day Saint missionaries. These missionaries had baptized the first three converts to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Reykjavík a year earlier, and one of those converts, Sigríður Jónsdóttir, happened to be the wife of one of the arresting officers. But a remarkable friendship, one that thrived irrespective of time, distance, and religious differences, developed in spite of the arrests and the events surrounding them. Although the story and historical context of the missionaries’ experience in Reykjavík have been explored before, this article focuses on the thrilling narrative of the friendship of these two Icelandic police officers. It is a story that demands attention by serious readers of Church history. Due to new source material, the article also provides new insights on several questions. How did the first Latter-day Saint baptisms come about in Iceland’s capital city of Reykjavík? How did the native Icelanders react to three of their women being immersed by foreign missionaries? Why were the Utah elders arrested? What was the reaction of the police officers who arrested them, knowing the wife of one of the police officers was one of these first converts? What developed from these conversions, and what is the rest of the story?

In 1881 Icelandic police officers Jón Borgfirðingur, above, and Thorsteinn Jónsson, below, were sent to arrest Latter-day Saint missionaires

In 1881 Icelandic police officers Jón Borgfirðingur, above, and Thorsteinn Jónsson, below, were sent to arrest Latter-day Saint missionaires

The story of the friendship between Thorsteinn Jónsson and Jón Borgfirðingur must first be situated in the context of the years 1855‒1914. Before World War I broke out, many Icelanders who had embraced the restored gospel immigrated to Utah.[1] There were nearly four hundred of them. In 1879 two of these Icelandic converts, Jón Eyvindsson[2] and Jakob B. Jónsson,[3] who were living in Spanish Fork, were called to return to their homeland to serve missions. They were two of a total of twenty-two Latter-day Saint Icelandic converts who were called to leave Utah and return to their country to serve as missionaries before World War I. The mission call of these two particular elders included a charge to preach in Canada on their way to Iceland. Thus they stopped briefly in Manitoba and New Iceland to labor among clusters of Icelandic emigrants; however, they did not remain long, for the people lacked interest in the missionaries’ message.[4]

Concerning their brief mission through Canada, the Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star reported: “They have, in accordance with a portion of their appointment, labored about three and a half months in Manitoba, in the Northern portion of British America, where about 2,000 Icelanders are located. During their ministry in that part they held seventeen meetings, three of which were in the open-air, the others in private houses.”

The article further notes that these missionaries “encountered malignant opposition, incited, for the most part, by Jón Bjarnason, who was a Lutheran priest. . . . The priest circulated many false reports concerning the elders and counseled the people not to listen to and to shut their house against them. The meetings were, however, attended by from sixty to one hundred persons, and they left some believing in the Gospel and intending to gather to Utah this autumn.”[5]

The elders scurried on to Copenhagen, Denmark, their base for Scandinavian missionary work, arriving on 12 September. Here they remained for about two months until an Icelandic tract written by Þórdur Diðriksson (Thordur Dedrickson), who was a prominent member of the Church, was published. It was titled Aðvörunar og sannleiksraust (A Voice of Warning and Truth), patterned after A Voice of Warning, by Apostle Parley P. Pratt.[6] Eyvindsson was appointed to preside over missionary labors in Iceland, with Jónsson serving as a second witness of the Restoration of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ.

Armed with Dedrickson’s lengthy Icelandic tract, the elders embarked on 8 November 1879, from Copenhagen for Iceland on the Phoenix, a postal vessel. On 23 November they arrived in Reykjavík, where they found no Latter-day Saints.[7] They therefore removed themselves to Vestmannaeyjar, where Einar Eiríksson presided over a small branch first established in 1853, the oldest in Iceland.[8] Here they remained until 19 December, when they returned to the mainland and recommenced their proselytizing efforts on foot to the northern region. By year’s end they were in a village named Gullbringusýsla, which lay about seventy-five miles northeast of Reykjavík.

Because of false information that preceded the elders, most residents would not receive their testimonies; it became nearly impossible for them to find any who would listen as they labored from house to house. Gunnar M. Magnúss, a prominent Icelandic writer and historian, notes in his book about nineteenth-century Reykjavík what took place when the missionaries headed northeast:

While away from Reykjavík, a few things happened that proved problematic for them when returning to town. There had been considerable talk about their arrival to the country[;] even articles had been printed. It was claimed they were dubious men who weren’t fit to be in houses together with decent people. Therefore, it wasn’t easy to find accommodation at this time. The icelandic hospitality they had enjoyed so much in their travels during the dark season, was absent. And because they were not fed in any of the houses, they bought dry fish, bread, and butter,—and ate wherever they found shelter from the weather. After a few days they were able to find accommodation in a house called Stöðlakot. Also, they received warm lunches, Jón Eyvindsson with a newlywed couple in Vaktarabær, but Jakob [received his lunch] in Götuhús. . . .

Stöðlakot was situated straight south of the High School library in Bókhlöðustígur. Many lived there, more than 20 persons permanently, so it was a situation well-suited for preaching. First to be named was a couple in their forties, three landless couples, all younger than forty, and two women around sixty who were related by marriage. Then there were three women in their prime years, two landless men, and several children. And finally, there was a theology student from the Priest College, 24 years of age, Jón Magnússon from Steinnes in Húnavatn County.

The Mormon priests commenced to talk to these people, especially in the evenings, and sometimes preaching when asked. They would flip open their scriptures and proclaim that people had to turn away from all evil, . . . be baptized by immersion for remission of sins, then everyone would receive the Holy Ghost by laying on of hands. All who wanted to be saved in God’s kingdom must obey these commandments. This was the first principle of the gospel. Then they would strongly criticize the Catholic Church and its teachings, but also Lutheranism, and, using Þórður Diðriksson’s own words, they pointed out the sad and dangerous situation of the Christian world.[9]

In this region they were able to hold a total of only five meetings. Civil authorities and local Lutheran clergymen combined to thwart their efforts here and in the adjoining counties, as well as in Húnavatnssýsla, where Jakob B. Jónsson’s mother and relatives lived. Yet in Húnavatnssýsla the elders held meetings nearly daily and then left for the principal city of Reykjavík in February 1880. They ran into problems, as Icelandic law required that they have jobs and not live off the people. Further, by this time a warning of their arrival was already in the press. The Reykjavík newspaper Þjóðólfur reported the following in an article titled “The Mormons,” dated 30 December 1879:

Mr. editor! Whereas 2 of our fellow Icelanders, who are Mormons, have arrived here with the last post ship from America with the intention to preach Mormonism here in this land, I would like to publish in your honorable magazine a warning to my fellow Icelanders, if any of them should be enticed to accept the Mormon faith, that the government in America had asked their officials[10] in the northern continent [meaning Europe] last spring to advertise in the papers in their countries, that no Mormons coming from the northern continent would get a residence permit in America, but they would be sent back again. . . .

It was for the same reason that the town sheriff here in Reykjavík prohibited the aforementioned Mormon priests to preach publicly here. These men are Jón Eyvindsson and Jakob B. Jónsson. They are young, neither unpleasant nor inarticulate. They have with them pamphlets for sale in Icelandic by Þórður Diðriksson who explains the main teachings of the Mormons and their origins.

The writer then provided a biased report of the origins of the restored Church of Jesus Christ, including a discussion of the plates of the Book of Mormon and a report of Brigham Young’s nineteen wives and a new Zion in Salt Lake City.[11]

In mid-March 1880, Eyvindsson wrote a letter to European mission president William Budge, stationed in Liverpool, reporting their early labors:

This is the first chance I have had to write to you since we came to our destination. It is the same here as we experienced in Canada: the people are blinded by priestcraft. We have traveled in many places and have had the opportunities to testify of the restoration of the Gospel to the people. The seed we have sown has not always fallen on good ground. . . . The sheriff and priests make opposition against us. They have forbidden the people to lend us their houses to preach in. We have had five meetings altogether. There is a great intolerance here. The priest has been around to try to convert the people again, but has had very little success in his endeavors. . . . It is difficult to get at the people to warn them, but it is the Lord’s work and He will bring it about. . . . We feel glad and happy to labor in His vineyard. The spirit of the mission rests upon us, and we talk by its influence.[12]

In articles published in Þjóðólfur, Egill Egilsson, a member of Iceland’s parliament and a member of the town council, and Theódór Jónassen, town sheriff and chair of Reykjavík’s welfare committee, vigorously debated the rights of Latter-day Saints to come to Reykjavík and preach. The town sheriff said there was religious freedom in Iceland and therefore his hands were tied unless the Saints preached something that threatened public morals, like polygamy. Egillsson, on the other hand, accused the town sheriff of protecting Jónsson and even insinuated that the town sheriff had a favorable view of the religion.[13] Further, another issue was the supposed vagrancy of the two missionaries, who had not applied for a permit to stay in the town of Reykjavík and were not employed.[14]

Despite the obstacles they had encountered, the missionaries’ painstaking labors on Iceland’s icy, rigid soil yielded some fruit by the time their mission concluded in July 1881. The result? There were twenty-eight baptisms, including the first Latter-day Saint converts in Reykjavík. These converts, baptized on 22 March 1880, were three women: Sesselja Sigvaldadóttir, born in 1858; Sigríður Bjarnadóttir, 1834; and Sigríður Jónsdóttir, 1846.[15] Their baptisms created no small stir in Iceland’s capital city. The baptism of Sigríður Jónsdóttir is of particular note in the story of Thorsteinn Jónsson and Jón Borgfirðingur, as Sigríður was the wife of Thorsteinn, one of the police officers who would soon arrest the missionaries who had baptized his wife. Eyvindsson wrote about this newsworthy event:

When the report spread about the baptism of these three sisters, the spirit of persecution was fiercely displayed by the people, and we were in danger from mobs. The lawyers accused us of rambling about in idleness [vagrancy], which is contrary to the law, because we travel about to preach the Gospel. . . . The magistrate of the town called us up twice for examination and finding us guilty of no crime, he banished us from the city and forbad us to preach. However we returned, and the chief of police put us in prison for two days. We were then taken before the magistrate again . . . [and ordered to] pay a fine of 100 Danish crowns each.[16]

Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur, the other arresting officer, kept a copy of the trial held in March 1881. The trial provided a public stage for Egill Egilsson and the Reykjavík town sheriff Theódór Jónassen to continue their debate about the rights of the missionaries to continue preaching. In the following quote, the sheriff is asking Egilsson the questions:

Questions and Answers:

1 How often have the Mormon priests preached?

Answer:

I don’t know exactly.

2 Name those places where they have preached.

Answer

I have done so in earlier issues of Þjóðólfur[17] namely in Staðarkot, in Helgastaðir, and I add for explanation in the home of police officer Þorsteinn in Vegamótastígur.[18]

3 Have the priests talked or taught about polygamy?

Answer:

Yes, they talked about that, as I can identify.

4 Where?

Answer:

In Grímsbær to the wife of Hans[19] and added that Sigga[20] had been married to a Mormon in America, and the relationship was so good between her and one of the other wives, that [Sigga] decided to name a child she had after [the other wife].

5 Can the witness testify or prove that they (Mormons) have disrupted peace in people’s homes?

Answer:

Yes, at Stefán Egilsson’s home, the peace of the marrage was destroyed and probably also at police officer Þorsteinn’s where a woman was baptized in a Fúlatjörn[21] unless he is a Mormon himself.

6 In what way have the Mormons contradicted Christian faith?

Answer:

They have disgraced the Lutheran faith and said that the Mormon faith was the only true faith, and whoever refused to accept it, was refusing the grace of God and would be sent straight to hell.

7 Can the witness give the names of those who heard that?

Answer:

Yes! Bogi Melsted, merchant Teitur Ólafsson, Kr. Ó. Þorgrímsson, Símon Bjarnarson.

The accused added to the first question that Jakob had told him that they had preached five times and the town sheriff had never prohibited them to preach last fall and winter.

And to the fifth question Egill demanded that it should be booked or noted that a promising young girl from the North [of Iceland, like Akureyri, or possibly from the same place as Jakob, as he was also from the North] that had stayed with Þorsteinn had to escape from there because the wife of police officer Þorsteinn had tried to force her into becoming a Mormon and Þorsteinn had tried so as well. The girl went to the bishop and asked his assistance and he told her not to stay with such people. Egill also provided an example of the Mormons’ disdain for our religion and Christian values. The example was from a time when Jakob came home to Götuhús [the name of the house where Sigríður Bjarnadóttir lived, not Thorstein’s wife, but her namesake] and Sigríður was then reading in the Psalms of the Passion [of Hallgrímur Pétursson, the most important religious text in Iceland after the Bible]. When Jakob saw this he said, “What old book is this that you are reading?” He took the Psalms from Sigríður and threw it in the garbage. To the wife of Hans [meaning Kristín Þórðardóttir, see above] Jakob has said that the Lutheran church was like a market and the priests like Jews [he is referring to John 2:16]. To those who sold doves he said, “Get these out of here! Stop turning my Father’s house into a market!”[22]

The Icelandic Mission Manuscript History notes that the preaching of these missionaries and the baptisms that followed “set the whole town in an uproar and the brethren for a long time afterward could scarcely walk the streets without being attacked and stoned by the mob. At last they were arrested by the police, charged with vagrancy, and imprisoned [for] two days.” They were then ordered to find employment. Elder Eyvindsson persuaded a “reliable man” to employ him as his servant, and Elder Jónsson set sail to fish for a limited period of time. The charge of vagrancy also required a fine of two hundred crowns, but the missionaries appealed their case to the supreme court, which overturned the decision of the lower court. The two missionaries were acquitted of the charges made by Egilsson.[23] Documents housed in the National Archives of Iceland evidence the arrival, travels, and arrest of these elders. The first was a letter to all the priests in Iceland written by the bishop of Iceland, Pétur Pétursson, dated 28 January 1880:

In a letter, dated 13th of this month, the provost [head of the priests] in Borgarfjarðarsýsla has told me about two Mormons, Jón and Jakob, who came here from Utah with the last post ship last fall, who traveled around in his parishes and held two seminars on two farms Hvítársíða [a farm on the bank of the Hvítá River]. The provost said he talked to them and forbade them to make any efforts within his parishes to spread their religious ideas, but they said they would return after having traveled to Húnavatnssýsla and some places in western Iceland. Last he knew, they were traveling around in Mýrasýsla [which is nearby], where they, as everywhere else they come to, drained the resources of the poor people they stayed with, according to him. He finally sought my help to protect the parishes in his area from the dangers and woes that the Mormon flock can cause among them.

Next, let me mention that as far as I know the secular administration has forbidden the Mormons to hold public seminars about their religious ideas, for they include things that cannot be regarded as common modesty—and such a prohibition is in my opinion absolutely necessary—let me mention that as dangerous the public seminars of the Mormons can be for people’s religious life and as necessary it is to hinder them, I believe that much more dangerous and destructive is their method to secretly walk as wolves in sheep’s clothing into the homes of people, stay there for days and deceive simple and poor residents, young and old. There are many examples of this, how Mormons have disturbed people’s peace in their homes and caught them in their net, not many actually, but more than they should have. In addition, these said Mormons, Jón and Jakob, have little means or are completely without money, they travel at least such as to pay little or nothing for their accomodation and service, and in that regard there is a full reason to make some measures as to hinder their group in this country.

Whereas there is little I can do about this matter without help from the secular administration, I would hand this matter over to the landchief; wouldn’t there be a full reason and high neccessity to order all concerning sysselmen [sheriff of the county of Vestmannaeyjar] to see to that the Mormons not only cannot hold their seminars about their faith, but also see to that they cannot travel at all throughout the settlements in such a way as just described, and where they violate this, they will be punished as a destructive and dangerous vagabonds and spreaders of false beliefs, according to the law of the country.[24]

Two months later, on 30 March 1880, Bishop Pétursson wrote to Hallgrímur Sveinsson, priest of Reykjavík Cathedral. The bishop wrote:

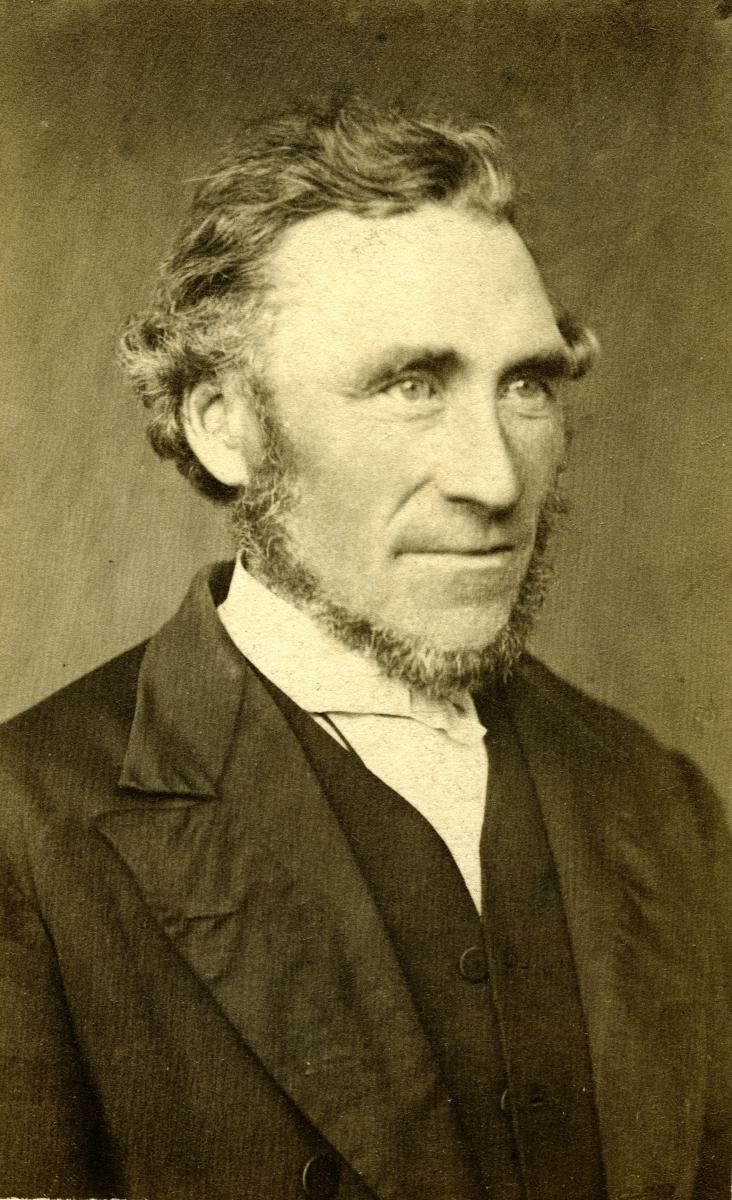

Pétur Pétursson, the bishop of Iceland, who wrote letters of opposition concerning Latter-day Saint missionaries preaching in Iceland in the late nineteenth century.

Pétur Pétursson, the bishop of Iceland, who wrote letters of opposition concerning Latter-day Saint missionaries preaching in Iceland in the late nineteenth century.

As you know, my dear sir, two Mormons are in town trying to spread their faith among the residents. Truly, they have been forbidden to preach here publicly; but the other thing is not less dangerous, perhaps even worse, that such men go unhindered from one house to another, preach there their false doctrines for the inhabitants and others who want to listen and are there, and thus they try to catch unwatchful souls. According to what is said, they have succeeded in getting three women, the widow of Sigríður Bjarnadóttir, Sigríður Jónsdóttir, the wife of police officer Þorsteinn, and Sezelía in Runólfsbæ, to deny their faith and be baptized into the Mormon faith. . . .

It has come to my mind to ask if you could not receive any help to talk to those women and try to turn them from their false ways, as we have heard that the Mormons have succeeded in catching them in their net. The men I had in mind are the priests reverend Helgi Hálfdanarson and Reverend Matthías Jochumsson, furthermore my clerk and Magnús Andrésson and the teacher Helgi Helgason. I truly don’t know what you have done so far in this matter, my beloved sir, but I completely realize that it is our duty as clergymen to combine our efforts to redeem the lost sheep from their spritual peril they are in because of the false doctrines of the Mormons, and thus I am sure that none of the gentlemen I just mentioned would deny you their help in this matter, if you see reason to ask them about it.[25]

Another document regarding the case of Elder Eyvindsson and Elder Jónsson was reported by the sheriff of Reykjavík:

Year 1880 Aug 9th case from the police department in Reykjavik: The community against Jón Eyvindarson. The verdict is as follows: In this case it is proven with admission of the accused and other things that he from the time he came to this land in November same year from Copenhagen has dwelt both in town and in other districts without having a legal job, but has only tried to persuade men to join the Mormon faith, which he himself professes. Whereas he has refused to give any information about if he has had enough money to live on since he came to the country, the police director banned him from town with a twenty-four-hour advance, and he left town then before that time, but returned the very same day, only to be arrested by the police director and he did not have any money at all. The official then ordered the case to be put for judgement, for illegal unemployment and wandering and for having violated the orders of the police director. At that, the charged has not been willing to give any information about him having any money to live on. . . .

When they [Mormons] are here to try to seduce people to accept the Mormon faith, which as well known teaches immorality, they therefore cannot have any protection by the law, even though there is freedom of religion here; the accused has, by returning to town in spite of the police director having banned him, brought upon himself a legal responsibility.

When evaluating a proper punishment the accused has inflicted upon himself, we should follow the orders from the royal statutes from May 26th 1863, 10th paragraph and from July 25th, 7th paragraph, and therefore the proper punishment seems rightful at thirty [crowns] that will go to the poverty fund of the town of Reykjavík, also the accused shall pay all legal expenses for this trial.

The verdict therefore is as follows: The accused, Jón Eyvindarson, shall pay a [thirty-crown] fine to the city of Reykjavik. He shall also pay all expenses for this legal trial and must do so within three days from the legal announcement of this verdict, or else should be put to trial again.[26]

This captivating event caught the attention not only of the Lutheran bishop and the Reykjavik sheriff and priest but also the leading Latter-day Saint periodical in Salt Lake City, the Deseret News, which made known that these Icelandic missionaries “suffered imprisonment and all kinds of persecution, which is against the laws of the land.” The journalist further explained, “The cause of this great persecution is that the Lutheran faith is universal in Iceland, and the Lutheran clergy have unlimited power there as there is no other sect in the whole country.” Yet the article concluded with glad tidings from Utah that such persecutions had led to conversions and the fact that “twenty-one Latter-day Saints emigrated this last summer from Iceland to the Valleys of the Mountains; they are all, at the present, in good health and spirits.”[27] What added even more excitement to the persecution and arrest of these Icelandic missionaries was that one of the three women baptized, Sigríður Jónsdóttir, was the wife of one of the arresting officers, Thorsteinn Jónsson.[28] The other arresting officer who labored with Thorsteinn was Jón Borgfirðingur, who noted the following in his journal about the missionaries and the baptisms that followed in March 1880:

Jakob [B.] Jónsson, originally from the North, and Jon Eyvindarson, originally from Rangárvellir, had gone to the Western Hemisphere, became Mormons there, came back here that fall and commenced preaching their faith here! They wandered to the North just before Christmas and returned back South in midwinter, because the people in Húnavatn District and Borgarfjörður drove them away [they] began again preaching and managed to convert some women to their faith, baptized 3 of them in the pools in [illegible]. . . . Setselja, the wife of stonesmith Stephán Gíslason, Sigríður Bjarnadóttir [illegible], and Sigríður Jónsdóttir, then living in Vilborgarkot, the wife of police officer Þorsteinn, where Jón stayed, but Þorsteinn would not be near there, for he feared to lose his position.[29]

Yet less than a month after the arrest, on 16 April 1881, Thorsteinn Jónsson was also baptized by Elder Jakob B. Jónsson.[30] He eventually quit his job, and the couple immigrated to Spanish Fork, Utah, in 1883 to join other Icelandic converts. Jón Helgason,[31] Iceland’s bishop, referred to Thorsteinn as “a mighty man to behold and very diligent, but he was caught up in the snares of the Mormon missionaries, which came here, and became a Mormon. Shortly he resigned his post and left for Utah.”[32]

Thorsteinn, Sigríður, and their foster son, Stefan Stefansson (also referred to as Stebbi),[33] were all recorded on the passenger list aboard the single-crew steamship Wisconsin, which embarked from Liverpool on 14 July 1883. Eighteen Icelanders on this voyage had arrived in Liverpool on 9 July. Thorsteinn is listed as fifty-two years of age; Sigríður, forty-one; and Stefan, four.[34] Two known letters from Latter-day Saint company leader John A. Sutton document this voyage. In one of the letters, Sutton notes: “With the assistance of the interpreter, I effected the organization of the Icelanders, and appointed Elder Thorarinn Bjarnason to take charge and have morning and evening prayer. . . . They appear to be very good people. I am studying Icelandic, with the assistance of a Danish and Icelandic Grammar.”[35]

On arrival on 24 July 1883, Sutton wrote a second letter to mission headquarters in Liverpool, which explained the following:

I wish to inform you of our safe arrival here at 6 p.m. on the 24th, all well, with one exception, that of Sister Jonsdatter [Sigríður Jónsdóttir]. She has been very sick all the way, and I did expect that she would have to stay in New York, but the doctor thought, as she was anxious to go on, she might be able to stand the trip. I do hope she will. Everything was done for her on board that could have been done. I have found it very difficult to make them understand, but, thank God, I have got along so far very well. Still I would rather take a company of a thousand English-speaking people. It has been very lonesome for me, with no one to speak to of our faith. We start this evening at 8 o’clock for home—yes, home sweet home in the mountains. God bless the people that are called Latter-day Saints who dwell there.[36]

This same group then traveled by train to Utah, arriving in the Salt Lake Valley on 30 July before migrating sixty miles south to Spanish Fork.[37]

Not only did Thorsteinn’s and Sigríður’s conversion leave an unforgettable memory in Icelandic Latter-day Saint history but Thorsteinn and his wife wrote nineteen letters between the years 1883‒96 to their friend Jón Borgfirðingur, the other police officer who arrested the Latter-day Saint elders in Reykjavík. Although Thorsteinn and Sigríður immigrated to Utah, Jón Borgfirðingur remained in Iceland, where he spent the remainder of his life until his passing in 1912.[38] But Thorsteinn and Borgfirðingur both promised to write each other until they died. Excerpts from these letters illustrate the cultural rhythms of Spanish Fork as well as a deep Icelandic friendship that could not be broken even by distance or religious orientation.

Painting of the harbor in Vestmannaeyjar in 1847, about the time the missionaries were teaching.

Painting of the harbor in Vestmannaeyjar in 1847, about the time the missionaries were teaching.

On 4 November 1883, Thorsteinn Jónsson began writing his first letter to Borgfirðingur. Thorsteinn wrote about his arrival in Utah. His wife and foster son Stebbi had made the journey with him as well. He also described integrating into the Utah community:

Apart from our seasickness, our trip went exceptionally well, but since we arrived here every day has been better than the other. Everyone has been good to us, both English and Danish, and whomever we have gotten to know. We now have most of [the] tools we need for use outdoors as well as in, and overall we feel as good as we did at home when we were at our best, except we have still not gotten ourselves a cow, even though we have been offered some. Apparently it is good for everyone here that bother to work, but others would have nothing to do here. . . . I have worked for a month doing construction and gotten about a dollar and half per day. For some time, I have been threshing wheat with a threshing machine and got a half a barrel of wheat per day. I wish all poor laborers would come here, to this town, Spanish Fork, rather than to all the other towns in the area. . . . It seems as if the average wage of people here is very good, both in monetary means and well-being, and people here are overall better off health-wise than at home. . . . The Lord has blessed us with many quality means for our bodies and souls since we have arrived. I am much better off and am more at peace walking these streets than I was in Reykjavík. I cannot thank the Lord enough for being here and being somewhat prepared for the winter, and I have stopped longing to be back in Iceland again.[39]

Two weeks later, 19 November 1883, Thorsteinn continued to add to his letter to Borgfirðingur. He noted:

We have been aided by the English and the Danish. I could have cried thinking of you at home, where you make so little and where the pay is so low. Our daily sustenance is wheat bread, potatoes, pork, meat, butter, pork lard and all sorts of fruits from the trees. . . . There are many here that have two estates, one here in town, but the other out in the countryside. . . . Nobody has a laborer, no matter how rich he is, whether he is superior or inferior, rather they let the horse teams work for them, machines, plows and other things like it. . . . Now I am better off here than I was in Reykjavík.[40]

Concluding his letter, Thorsteinn earnestly invited Borgfirðingur to leave Iceland and to come live in Utah:

I wish you were settled here with your family, and I cannot feel sorry for your sons that they are working for you. . . . I am certain that you and your family need to gnaw the ice, as people seem to do in the old country. I come to tears thinking about my poor countrymen, that don’t have anything else to tread on but rocks, instead of cornfields and other kinds of vegetation. Oh, that I were about twenty. Oh, you young men; are you going to stand there idle on those frozen rocks, without thought, without action, yes, frozen to the core in both soul and body, and search not out the warmer parts of the world, where you can become men of doing, both for yourselves and for others.[41]

A letter written the following year as spring was about to dawn provides many details about a variety of activities in Spanish Fork:

There are three shopping areas, two butchers, two bars, one theater, one church, four sawmills, one meal mill, which is water powered, and it is used a lot. Then they are building a woodworking machine, which is supposed to be water powered, that makes windows, doors and all kinds of things. There are two trains that run here, one right below the town, but the other right above it, and the wagons run to and fro on them many times a day, so much so that one can almost expect news on the hour, yes, even every minute with the telegraph. [Yet] no one here has any Icelandic newspapers. . . . Seeds are quite expensive here like some of these trees, but we, through the grace of our Lord, have become so well respected, both of the Danish, English, American, and Icelandic, that we have been given all of it. I was amazed at one thing last Saturday night. In a meeting that was held, my testimony from the old country was read verbatim by an American man, which is a counselor to the bishop in Spanish Fork. It is good to do well and to receive a reward for your actions. . . .

I am as content now as I ever can be with my circumstances and I hope that I may live here the rest of my days in peace and trust that I will not have to travel to Iceland ever again, rather remain here in peace and enjoy all the blessing of the Lord.[42]

In the summer of 1884, Thorsteinn wrote to Borgfirðingur and described the 24 July celebrations in their community. The holiday marked the anniversary of Brigham Young and the Saints entering the Salt Lake Valley in 1847:

The biggest celebration of the year is on the 24th of this month. Then everyone will dress up in the costume they brought from their fatherland or motherland. Old man Hansen . . . will appear in his uniform and two medallions for his bravery as a general. He is Danish. Then you can see how high people have been in their homeland. I will also appear all dressed in my uniform and claim my respect from the townspeople. Do you think I will be proud?[43]

Thorsteinn described to Borgfirðingur the 24 July parade and how the Icelanders and all the other Latter-day Saints marched in it. The letter also demonstrates the pride that Thorsteinn and Sigríður still felt for Iceland:

There was a great festival held here the 24th of July, naturally the biggest one of the year. Then they called on a few men of every nation to show their national costumes and various traits, to display one’s status and crafts, which they brought with them from home. Of the Icelanders they called Þórður Diðriksson to bring six Icelandic persons. He called my wife and I, Gísli Bjarnason and Margrét, the wife of Samúel, Eiríkur Ólafsson and Margrét, who was in the school.

At eight o’clock in the morning everyone was to assemble by the city hall, and there everyone was ordered into groups. First were the English and the American, Swedish, Danish, Icelandic, German, all in wagons, which were decorated with cloths and upholstery of various colors. There were also 24 young men and women on horseback, riding side by side, the boys all dressed in black on gray horses, but the girls on brown horses all dressed in white. This was to represent the 24 days of the month. Then they all rode along the main street, three times around so that all could see, because the sidewalk on both sides was so crowded. Then we went just outside of town to a forest, which was planted for pleasure. There were speeches and singing, then lunch was served and we ate, and after we played games. Those who had been officers or lieutenants came in their costumes, each in their own rank that they had held at home. I came in my policeman uniform and it was considered striking. My wife was in her national costume, which was considered the most beautiful costume they had ever seen, and I think most of the people that were present came to look at the costume, it was thought to be so significant. The Icelanders also made a symbol for the group from blue linen, with a falcon on one side, and a Viking ship on the other side, according to Friðþjófur. This was also considered beautiful. The Icelanders also carried a symbol made out of white linen with big blue inscription, saying: Iceland delights in you, Zion. I wish it were so; however, it meant the Icelanders that are here and all of those who might come. They also showed how they looked when they first arrived, walking with their belongings in handcarts, with their children barefoot, torn and tattered, crying because of hunger and exhaustion. But now they have lands and acres. But those who come now, come like soldiers in covered wagons, but must in return work as a servant for the others, because they’ve made the lands so expensive that you can scarcely buy them. It is not the Lord’s doctrine that this should be so. This festival is to commemorate the restoration of the Church, the 24th of July. The wife and I sought to bring as much honor as possible to our nation. It is considered a great honor to all, irrespective of their nationality.[44]

After living several years in Spanish Fork, in 1889, Thorsteinn, known as “Thorsteinn the poli or policeman,” and Sigríður moved to Castle Valley, Utah.[45] They then moved again; the Icelandic Mission Manuscript History notes that Thorsteinn and Sigríður “took up land there [in Cleveland], and have lived there and since done well.”[46]

The reason for the move is evident from another letter Thorsteinn wrote to Borgfirðingur from Cleveland in late December 1890: “I am still above ground and doing well, but I have moved like the devil a hundred miles west of where I was. I had to go somewhere I could buy land because I have so many animals. I bought thirty acres of land for a dollar and a quarter an acre, so I have spent every effort to build a home.” In this same letter, he notes that a few other Icelanders had migrated to this area. He mentions Einar Eiríksson, his son Einar, as well as Jakob B. Jónsson, his wife Sigríður, as well as three other Icelanders he does not reference by name.

It is also evident that Thorsteinn still cannot forget Iceland. He then asked Borgfirðingur, “What shall I send you for the best newspaper in Reykjavík . . . ? How much shall I send Eymundsen to get a picture of the harbor with the shipping fleet and that side of town, which faces the sea?” Further, he stated, “I wish I could be there for Christmas with my horses and wagon to drive around the streets of Reykjavík with you and the others.”[47]

As 1891 drew to a close, Thorsteinn told his friend: “My sight is getting worse. Therefore, I don’t suppose you will be able to get through it [the letter] and thus it is best not to have it too long.”[48] Thorsteinn then wrote of vicarious work to save the dead and added the names of people for whom they were seeking to do temple ordinances. Concerning his wife, he wrote: “She says she lacks no earthly possession, but what she needs is for someone to kindly send her . . . thousands of names of deceased persons to do work for them in the house of the Lord. . . . For it is my heartfelt wish to be a saving and blessing instrument in the hand of God, both for the living and for the dead, as they didn’t do this for themselves.”[49]

The names Thorsteinn and Sigríður requested from Borgfirðingur for vicarious temple work were provided in a letter they received from him on 10 May 1892. Thorsteinn replied to his friend, “My wife sends her regards and thanks you wholeheartedly for the information, which you have given her in your kindness, and you will be blessed for it.” Referring to books that recorded the ordinances that had been completed for the dead, he added: “Those who have rejected this [work], don’t have the books that you mentioned for their arguments sake when they arrive on the other side of the veil, and will have wanted to do something different. But everyone has agency to govern his own words and actions in this life.”[50]

As the new year of 1894 dawned, Thorsteinn reminded Borgfirðingur of a promise they made: “You may think that I was deader than a doornail, but it is not so, and I have not forgotten my vow either, which we made to each other when we departed, to write one another as long as we lived. I also believe that you are alive, because I have not read of your death in Heimskringla.”[51]

Thorsteinn then noted that two more Icelandic missionaries were to be sent from Utah: “Þórarinn Bjarnason, a fine man and reliable in word and deed,” and “Jakob B. Johnson, who previously went on a mission with Jón Eyvindsson, whom I give no recommendation; for he can recommend himself wherever he will be. . . . I wish people would accept them gracefully to their honor and blessing.” He then shared the glad tidings of the completion of the Salt Lake Temple and added that Sigríður had attended the dedication.[52]

Eight months later, Thorsteinn received a letter from Borgfirðingur, and the following month he wrote back, explaining: “Our economy is about the same as it was last time I wrote, we have 11 cattle, 4 horses, 21 pigs, I don’t know how many hens. This summer we have gotten a machine to mow grass, which cost 65 dollars, and a third part in another to cut wheat. . . . Stebbi . . . is working with them. It was a day of fortune when we took that [foster] child.” The letter concluded: “My sight has gone, but I am otherwise in good health. Sigríður and Stebbi send their regards. Yours almost blind.”[53]

Thorsteinn acknowledged receiving another letter from Borgfirðingur on 3 June 1896. He replied two months later in the last known letter to Borgfirðingur, dated 10 August 1896. This concluding letter ended with the last words he would write to his friend:

Good friend, as you can see by these lines I am in no shape to write myself, because I am almost blind. Neither can I read your letters, but my wife does that (if she has enough time), and I hope that it does not become a hindrance for you to write me. I have no news except my well-being, which is the same as when I wrote you in Akureyri in the fall of 1894, and I hope you received that letter. In that letter I sent you a picture of the machinery. The writer has no more time to spare and my wife will complete the letter. Yours gray and almost blind well-wishing associate Th. J. Guðnason.[54]

Sigríður then began asking questions about various people, apparently to gather information to continue her consecrated efforts to redeem the dead:

Now I start my queries, but please write my husband a letter, what do you know about the relatives of the late Sigurlaug Þorkelsdóttir, the [previous, now-deceased] wife of my husband . . . Mrs. Hjálmarsen, Þorsteinn [kanselliráð], his wife, old Mrs. Jónassen, Þórður Jónassen and his mother, the widow of rev. Þorlákur on Undirfell in Vatnsdalur, the widow of rev. Jón in Steinsnes, the widow of rev. Ólafur Pálsson provost (archdeacon), Guðrún Ólafsdóttir, Guðrún on Arnarnes the widow of Stefán, the widow of sheriff P. H. How is Óli kransi doing? How I love your book on the collection of authors but there should have been more women’s names. I don’t understand what it means that the names of icelandic women and girls are hardly possible to extract. I think it a beautiful sign of education and honor for Iceland to work on the genealogy in the lines of both the father and the mother as far back as possible, even all the way back to Adam (we don’t need to worry about finding Cain as one of our forefathers). . . . I am going to the temple when I can.[55]

Now nearly blind, Thorsteinn would not write any more letters until his death a decade later, on 9 February 1906. Sigríður continued to live in Cleveland and passed away on 17 April 1928. The remainder of her life was probably spent working to redeem her kindred people.[56]

The conversion of Thorsteinn and Sigríður sheds light on the challenges facing Icelandic converts in the nineteenth century and opens a window into the past to understand the bond between Western Icelanders and their homeland, regardless of the thousands of miles that separated them from family and friends. The correspondence between Thorsteinn and Sigríður with Jón Borgfirðingur reveals a wonderful friendship that continued many years after they left Reykjavík for Utah. This cache of letters is a wonderful reminder of the rich Icelandic heritage that connected this Nordic people and continues to link them to the present day.

Notes

[1] The mission was reopened by Byron Geslison (whose parents were Icelandic Latter-day Saints), along with his wife, Melva, as well their twin sons, Daniel and David, in 1975.

[2] Jón Eyvindsson was thirty-five years old at the time of his mission. He was born in 1844 on the the farm of Hallgilseyjarhjáleiga in Rangárvalla County. Jón was mainly raised as an adopted boy in Syðri-Úlfsstaðir in the area of Landeyjar and was confirmed in the parish of Kross in the same area. There he dwelt in his home community without any notable events in his boyhood. It was unfortunate he broke the ethical code in his society and was punished for it. When he was twenty-seven years old, he went over to the Vestmannaeyjar to look for a job and dwelt there for about one year. There was good soil, on the isles, for the message of the Latter-day Saints. Jón Eyvindsson heard about it and liked it. From the Vestmannaeyjar he headed north, stopped in Húnavatns County, and dwelt there in several places: Spákonufell, Háagerði, and Skagaströnd for a year and a half. Now his mind turned to the West because ways to travel to America had opened up, and he went to Salt Lake City, Utah. In the Salt Lake settlements, he dwelt about a year but was then commanded to go back to his own country to preach his faith there. First he went to Manitoba and stopped there for three and a half months, but then embarked for home [Iceland] in the month of August, first with a vessel to the mainland of the Northern Continent (Europe) and then arriving here. Gunnar M. Magnúss, Langspilið ómar: 1001 nótt Reykjavíkur II., 1958, [7]–8.

[3] Jakob Baldvin Jónsson, thirty-six years old at the time of his mission, was from Húnavatns County, born at Bergstaðir in Vatnsnes. He dwelt in Vatnsnes until he was seventeen or eighteen. Then he spent the next two years at different farms in Húnavalla County and in Skagafjörður County: at Illugastaðir and Heiðarsel. Then he went to South Iceland, first as an employee in Engey, then in Gufunes. From there he went to Reykjavík and worked there until he embarked for America in 1876. He went to Salt Lake City. There he was baptized and then later set apart as a missionary to preach in his home country, just like his companion, Jón Eyvindsson Magnúss: Langspilið ómar, 8. The story of Elders Eyvindsson and Jónsson is also told in Fred E. Woods, Fire on Ice: The Story of Icelandic Latter-day Saints at Home and Abroad (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2005), 76–79.

[4] Andrew Jenson and staff, comps., “Manuscript History of the Iceland Mission (1851‒1914)” for the years 1879‒80, 21‒22, Church History Library, Salt Lake City (hereafter cited as MHIM); Einar Eiríksson, “A Short History of Iceland,” 7‒8, in possession of author. Unfortunately, the author could not find any newspapers in the Province of Manitoba (New Iceland was considered part of Manitoba by 1887) that mentions anything about Icelandic missionaries passing through this area in 1879.

[5] “The Gospel to the Icelanders,” Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star (hereafter cited as Millennial Star), 15 September 1879, 587.

[6] Dedriksson’s work proved to be the most successful proselytizing tool used by Latter-day Saint missionaries in Iceland for the next century, until the Book of Mormon was translated into Icelandic in 1981. See Woods, Fire on Ice, appendix A for a translation of this entire manuscript into English. Gunnar M. Magnúss noted they had brought an Icelandic book which they often flipped open and read from. Called A Voice of Warning and Truth, it discussed the main concepts of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It was written by Þórður Diðriksson and published by N. Wilhelmsen in Copenhagen in 1879. It was a small book, with 165 pages divided into eight chapters. But the book was like a well—one could always drink from it and it never became dry. Magnúss, Langspilið ómar, 11.

[7] Magnúss, Langspilið ómar, 7, 10.

[8] The first Icelandic branch was established on 19 June 1853 on the island of Vestmannaeyjar.

[9] Magnúss, Langspilið ómar: 11–12.

[10] This publicity stems from a letter which William M. Evarts, secretary of state for the United States, sent to European diplomats in an attempt to keep European converts from coming to America, as he supposed they were polygamists, and he wanted to eradicate this practice in the United States. See William Mulder, “Immigration and the Mormon Question: An International Episode,” Western Political Quarterly 9, no. 2 (June 1956): 416‒33, for more information on this episode.

[11] “The Mormons,” Þjóðólfur, 30 December 1979. The Langspilið ómar notes that as soon as Jón and Jakob were on dry land in Reykjavík, the news spread around town that two “Mormon priests” had arrived. People had heard about Latter-day Saint behavior and lifestyle, and “the real” Christians didn’t like it. In one part of the country, which you might call Iceland’s extreme point in the south, the Saints had settled there twenty to thirty years earlier, and from there many stories circulated the country, especially stories of their polygamy. Even if many Icelanders considered the Church interesting, it wasn’t so easy for them to reject their current beliefs about morality, religion, and family and join the Church, so proselytizing success wasn’t as much as missionaries hoped for. But when the news spread about the arrival of these missionaries, strong men in the prime of their life, many expected that they would be incorrigible women hunters and deceivers who, in the name of religion, would lead people away from morality.

There was a law in the country that people had to be self-sufficient in order to travel from town to town. Travelers needed documentation that proved they had possessions in Iceland that were equivalent to five hundred [old Icelandic measurement], or they had to be learned craftsman. This law was to prevent travelers simply leeching off of the goodwill of townspeople. Otherwise, people had to register as employees. These ordinary workers were essentially de facto slaves.

The missionaries then visited the town sheriff in Reykjavík and announced that they had come to preach the faith of the Latter-day Saints.

The town sheriff had a difficult case in his hands. There was freedom of religion in Iceland, but after considering the matter, he thought it was irresponsible to allow the missionaries to preach their heresy and spread polygamy. On the other hand, he believed there was no actual reason to drive them out of town at the moment, for they said they were only going to stay there a short time. So, for the time being, he said he had nothing against them being in town but prohibited them to preach publicly or outdoors. Magnúss, Langspilið ómar, 8–9.

[12] Letter from Jón Eyvindsson to William Budge, 18 March 1880, in “Missionaries in Iceland,” Millennial Star, 5 April 1880, 221.

[13] “Mormons in Reykjavik,” Þjóðólfur (16 January, 2. blað 1881); “Mr. Editor,” Þjóðólfur (29 January, 3. blað 1881); [Egill] Egilsson, Þjóðólfur (26 February, 5. blað 1881); E. Th. Jonassen, Þjóðólfur (12 March, 6. blað 1881). [Egill] Egilsson, Þjóðólfur (26 March, 7. blað, 1881).

[14] “Mormons in Reykjavik,” Þjóðólfur (16 January, 2. blað 1881). Further, in Þjóðólfur (16 January, 2. blað 1881), Theódór Jónassen defends Reykjavik’s welfare committee, of which he is the chair.

[15] Woods, Fire on Ice, 93, endnote 14.

[16] Letter of Jón Eyvindsson to President William Budge, Millennial Star, 31 May 1880, 350. The arrest of these missionaries and the charge of vagrancy are attested in the Icelandic Reykjavik newspaper Isafold, 9 April 1880, 36.

[17] See Þjóðólfur, 16 January, 2. blað 1881, 6.

[18] Vegamótastígur is the name of the street where Thorsteinn lived.

[19] This is Hans Jónsson, and his wife was Kristín Þórðardóttir. See http://

[20] Sigga is Ingibjörg Sigríður Jónsdóttir, who became the plural wife of Jón Jónsson. See Jón Helgason, Íslenskt mannlíf 4:181.

[21] The usage of Fúlatjörn (sour pond) is a reference to a place where these baptisms took place, a pond or coastal lagoon east of where Borgartún now is and that disappeared about 1960. See Guðjón Friðriksson, Alfræði Reykjavíkur, http://

[22] Journals of Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur, vol. 1 (1860‒1884), March 1881, University of Iceland, kept on loose paper at the end of his journal.

[23] MHIM, 1880, 23. See also Magnúss, Langspilið ómar, 7–64.

[24] Letter from the bishop of Iceland, Pétur Pétursson, Bps C, III, 53, no. 20 (1880): 243‒44, National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Reykjavík, Iceland.

[25] Letter from the bishop of Iceland, Bps, C, III, 53, no. 91 (1880), 285‒86, transl. by Gerhard Gudnason.

[26] Sýslumaðurinn Reykjavik 7, nos. 6 7. Dómabækur 1873‒1881, tran. Gerhard Gudnason. Following is the exact same letter, trial, and verdict, only this time for Jakob Jónsson.

[27] MHIM, 1880, 26.

[28] David Alan Ashby, Icelanders Gather to Utah 1854‒1914 from Iceland to Spanish Fork, Utah (Spanish Fork, UT: Icelandic Association of Utah, 2008), 112, writes “Sigríður Jónsdóttir (Sigridur Jonsdottir) was born in 1844 [1842] in the parish of Thykkvabaejarklaustur, Vestur Skaftafell. She is the daughter of Jon Bjarnason, born in 1805, brother of Einar, the poor district director in Hrifunes, Asar i Skaftartunga, Vestur Skaftafell; and Domhildur Jonsdottir, born 1823. She is sister to Bjarni Jonsson (Bjarni Jónsson). . . . Sigridur and Thorsteinn [Jónsson] (Þorsteinn Jónsson) immigrated to Utah in 1883 with their foster son, Stefan Stefansson (Stefán Stefánsson).” However, Find a Grave displays a grave marker in the Cleveland, Utah, Cemetery that shows her birthdate as 3 July 1842, which appears to be correct.

[29] Journals of Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur diary, vol. 1 (1860‒1884), March 1880, University of Iceland.

[30] MHIM, 1881, 27. In the 1882 Reykjavík Parish Census, Thorsteinn’s age is listed as forty-six and his status as police officer. The age of Sigríður is noted as thirty-nine. Appreciation is extended to the staff of Reykjavik City Archive for providing this information.

[31] It is not clear why such a prominent Icelandic bishop and historian would have taken note of Thorsteinn. Bishop Helgason was only fifteen in 1881. Whatever the reason, he decided to highlight Thorsteinn while writing his 1941 book about people who stood out in Reykjavík.

[32] Finnur Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim: Fráíslenzkum mormónum í Utah (Reykjavík: Setberg Publishing, 1975), 13–14; excerpts from this book were translated by Fridrik Gudmunsson. See also Woods, Fire on Ice, 53. However, the original letters, housed in the University of Iceland manuscripts division, were also examined; additional translations and modifications from Gudmundsson’s work were made by Gerhard Gudnasson and Kári Bjarnason. David Ashby, Icelanders Gather to Utah, 128, notes, “Þorsteinn Jónsson (Thorsteinn Jonsson) was born 13 May 1830, the son of Jon Gudnason (1799-1862) and Gudrun Andresdottir (1801-1880). They farmed at Strandarhofda, Breidabolstadir i Fljotshlid, Rangarvalla. Thorsteinn joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and was baptized 16 April 1881. His wife, Sigríður Jónsdóttir, was born in 1845, the daughter of Jon Bjarnason, brother of Einar, the poor district director in Hrifunes, Asar i Skaftartunga, Vestur Skaftafell; and Domhildur Jonsdottir, born 1823; and the sister of Bjarni Jónsson, born 12 September 1854, who also immigrated to Utah. Sigríður and Thorsteinn immigrated to Utah in 1883 with their foster son, Stefan Stefansson, born 21 November 1875 in Reykjavík, Gullbringu, the son of Anna Sigurdardottir, born 1840 in the parish of Helgafell on Snaefellsnes, a maidservant in Reykjavik from 1872 until she died there 27 November 1911. They moved to Castle Valley in 1889 and took up land there; they did well. They lived in Cleveland.” See also MHIM, 2, 77. One reason why Thorsteinn and his wife, Sigríður, moved to Cleveland may be because one of the missionaries who taught them the gospel (Jakob B. Jónsson) had already moved there in 1886.

[33] Ashby, Icelanders Gather to Utah, 119, states that Stefán Stefánsson “was born 21 November 1875 in Reykjavik, Gullbringu, the son of Anna Sigurdardottir, born 1840 in the parish of Helgafell on Snaefellsnes, a maidservant in Reykjavík from 1872 until she died there 27 November 1911. She was the daughter of Sigurdur Sigurdsson, born in 1805; and Gudrun Jonsdottir, born in 1812. They farmed at Helgafell on Snaefellsnes. Anna claimed Stefan Palsson, born 1853 in Reykjavik, Gullbringu, the son of Pall Magnusson and Margret Gisladottir, to be the father of her child. He denied this, but the Reykjavik city court legitimated Anna’s claim. According to the 1880 census for Reykjavik, Stefan Stefansson was in Thorsteinn Jonsson and Sigridur Jonsdottir’s household as a parish pauper. He is not listed in the emigration records. (Reverend Kristjan Robertsson says in his book Gekk ég yfir sjó og land that Stefan was Thorsteinn and Sigridur’s foster son.)” Stefan was also known as Steven Johnson. He died 6 October 1944 and is also buried in the Cleveland, Utah, Cemetery, where his foster parents are also buried. See https://

[34] See passenger list of July 1883 voyage of the Wisconsin on the Mormon Migration website, chief editor and compiler Fred E. Woods, https:/

[35] “Emigrants from Iceland,” letter written by John Sutton, 15 July 1883, Millennial Star, 23 July 1883, 479; Woods, Fire on Ice, 81–82.

[36] Letter of John A. Sutton, Millennial Star, 13 August 1883, 527.

[37] Compilation of general voyage notes, https:/

[38] For more biographical information on Jón, see Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur, 1826‒1912, Skimir 87, árganur 1913. He is buried in the old Reykjavík Cemetery, just north of the University of Iceland campus. The Icelandic name of the cemetery is Hólavallagarður. His name appears on his stone marker.

[39] Letter of Thorsteinn Jónsson in Spanish Fork to Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur in Iceland, 4 November 1883, National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Catalogue # Lbs IB 102, fol. B (w-ö), 1–2; Woods, Fire on Ice, 53–54. See also Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 53–55.

[40] Second part of letter by Thorsteinn Jónsson in Spanish Fork to Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur in Iceland, 4 November 1883, (letter continued 19, 29 November 1883) National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Catalogue # Lbs IB 102, fol. B (w-ö), 1–2; Woods, Fire on Ice, 54–55. See also Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 55–57.

[41] Final part of letter by Thorsteinn Jónsson in Spanish Fork to Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur in Iceland, started 4 November 1883 (12 December 1883), National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Catalogue # Lbs IB 102, fol. B (w-ö), 1–2; Woods, Fire on Ice, 55. See also Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 58.

[42] Letter by Thorsteinn Jónsson in Spanish Fork to Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur in Iceland, March 18, 1884, National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Catalogue # Lbs IB 102, fol. B (w-ö), 2–4; Woods, Fire on Ice, 55–57. See also Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 63–64.

[43] Letter by Thorsteinn Jónsson in Spanish Fork to Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur in Iceland, 15 June 1884, National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Catalogue # Lbs IB 102, fol. B (w-ö), 3; Woods, Fire on Ice, 57. See also Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 68. Inasmuch as Thorsteinn mentioned this holiday (known in modern times among Latter-day Saints as “Pioneer Day”) was about to occur on the “24th of this month,” perhaps he made a mistake in dating this letter, and it was really written on 15 July 1884. Furthermore, Thorsteinn notes that this was the “biggest celebration of the year.” In a previous letter (the fourth part of the first letter he wrote to Jón) dated 28 December 1883, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 59, Thorsteinn wrote to Jón, “They don’t celebrate Christmas here much, except for the Icelandic, but that is because they say the birth of the Savior did not occur that day, and that is true. Some say that it is the 6th of April.” The suggestion that Christ may have been born on 6 April, instead of the traditional date of 25 December, stems from a book of scripture called the Doctrine and Covenants, section 20, verse 1, which notes that the day the restored Church was organized was 6 April 1830, “one thousand eight hundred and thirty years since the coming of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ in the flesh.” However, other Church leaders disagree with this position. For discussion regarding both sides of this interpretation, see Bruce R. McConkie, The Mortal Messiah: From Bethlehem to Calvary, Book 1 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1979), 349–50.

[44] Letter by Thorsteinn Jónsson in Spanish Fork to Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur in Iceland, 4 August 1884, National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Reykjavík, Iceland. Catalogue # Lbs IB 102, fol. B (w-ö), 1–3; Woods, Fire on Ice, 57–59. See also Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 69–71.

[45] Ashby notes that Thorsteinn and his family moved to Cleveland, Utah, in 1889. See Ashby, Icelanders Gather to Utah, 112.

[46] MHIM, section 2, 77.

[47] Letter of Thorsteinn Jónsson in Cleveland, Utah to Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur in Iceland, 20 December 1890, National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Reykjavík, Iceland. Catalogue # Lbs 102, fol. B (w-ő); Woods, Fire on Ice, 66–67. See also Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 111. Sigfus Eymundsson was considered the best photographer in Iceland during the nineteenth century.

[48] Letter of Thorsteinn Jónsson in Cleveland, Utah to Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur, in Iceland, 31 December 1891, National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Reykjavík, Iceland. Catalogue # Lbs 102, fol. B (w-ő). See also Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 114.

[49] Letter of Thorsteinn Jónsson in Cleveland, Utah to Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur, in Iceland, 31 December 1891, National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Reykjavík, Iceland. Catalogue # Lbs 102, fol. B (w-ő). See also Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 115. One of the names requested was Count Trampe, who served as the governor of Iceland, representing Denmark in the nineteenth century.

[50] Letter of Thorsteinn Jónsson in Cleveland, Utah to Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur, in Iceland, 28 June 1892, National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Reykjavík, Iceland. Catalogue # Lbs 102, fol. B (w-ő). See also Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 122.

[51] Heimskringla was an Icelandic-Canadian newspaper established in Manitoba commencing in 1886.

[52] Letter of Thorsteinn Jónsson in Cleveland, Utah, to Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur in Iceland, 3 January 1894, National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Reykjavík, Iceland. Catalogue # Lbs 102, fol. B (w-ő). See also Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 124‒25.

[53] Letter of Thorsteinn Jónsson in Cleveland, Utah to Jón Jónsson Borgfirðingur in Iceland, September 30, 1894, National Library of Iceland, Archives Department, Reykjavik, Iceland. Catalogue # Lbs 102, fol. B (w-ő). See also Sigmundsson, Vesturfarar skrifa heim, 128‒29.

[54] Here Thorsteinn is using an abbreviation of his first and second names but also adds the last name of his father, Jón Guðnason. Jón Borgfirðingur was living in Akureyri in 1894.

[55] Sigríður signed her name Sigga J. Guðnason, since her husband was now using the last name of Guðnason, instead of Jónsson.

[56] This information is found on a joint grave marker; both Thorsteinn and Sigríður are buried in the Cleveland Cemetery, https://