Christmas and Childhood

James R. Kearl

J. R. Kearl, “Christmas and Childhood,” Religious Educator 2, no. 2 (2001): 109–120.

J. R. Kearl was the A. O. Smoot Professor of Economics at BYU and Assistant to the President for the Jerusalem Center when this was published. He is a former Dean of General and Honors Education and Associate Academic Vice President.

Christ with St. Joseph in the Carpenter's Shop, by Georges de La Tour (1593-1652). The Louvre, Paris.

Christ with St. Joseph in the Carpenter's Shop, by Georges de La Tour (1593-1652). The Louvre, Paris.

Each year, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints join much of the Christian world in celebrating Christmas. And each year, the approaching holiday season causes me to think about the contrast between Christmas and Easter—the other great celebration of Christ’s life. I invite everyone to join me in reflecting on the distinctive spirit of the Christmas season and its associated celebration of Jesus’ birth. In particular, I invite good people everywhere to think about the words and associated memories that come to mind when we think of the word Christmas. For me, words like expectation, anticipation, hope, potential, awe, wonder, spontaneity, joy, and curiosity capture some of the feel of Christmas.

Now think for a moment about the word Easter. Are your thoughts the same as when you reflect on the meaning of Christmas, or do you see in your imagination and feel in your hearts something slightly different? I do. When I think of Easter, words like fulfillment, realization, and triumph seem to best capture my feelings.

For me, the difference between Christmas and Easter parallels the music we commonly sing at Christmastime: “Silent Night,” “With Wondering Awe,” “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” or “Away in a Manger.” These traditional Christmas hymns have a softness and tenderness that whispers, “Shush—there’s a babe over there lying in a manger.” By contrast, when I think of moving or inspirational Easter hymns, I think of “He Is Risen,” “Christ the Lord Is Risen Today,” or similar majestic anthems that in their voicing proclaim, “Christ is triumphant!”

This difference between the quiet potential of Christmas and the acknowledged realization of Easter is also manifest in scriptural records. Consider, for example, the account of angels announcing the Messiah’s birth to a few shepherds in the hills near Bethlehem. While these same angels joined heavenly hosts in singing “Glory to God,” they apparently did so to only a handful of earthly observers, as we find no scriptural evidence of a widespread understanding that Jesus Christ, the Son of God, had just come to earth as a mortal infant.

By contrast, at the beginning of the last week of His life, Jesus rode triumphantly into Jerusalem on a donkey, through streets mobbed by people spreading a carpet of palm fronds at His feet. While virtually all would abandon Him by the end of the week and demand His crucifixion when offered the choice between freeing Him or Barabbas, at the beginning of the week, there could not have been many people in Jerusalem or in the surrounding area who did not know that Jesus had arrived in the city.

For me, the difference between Christmas and Easter is also illuminated by a stunningly beautiful painting I first saw in the Louvre nearly twenty years ago. I was wandering around at the end of a long morning, a bit numb and almost overcome by a museum as large and rich in visual delights as the Louvre. As I turned a corner, I saw the painting by Georges de la Tours. It is entitled simply St. Joseph the Carpenter.

From the first moment I saw this painting, I was completely enthralled by its beauty and peace. Obviously, thousands—perhaps tens of thousands—of nativity paintings and other images depict Jesus as an infant, typically with His mother Mary. Probably an equal number are devoted to His ministry, His suffering in Gethsemane and on the cross, and His subsequent Resurrection and ascension into heaven.

But the de la Tours painting is one of only a handful of works of Jesus as a boy. It has become my favorite painting. If I am in Paris, I make something of a pilgrimage to the Louvre to be inspired and calmed by it. I am so taken by it that a couple of years ago when my three eldest children were returning from study at the Brigham Young University Jerusalem Center, I agreed to pay for a hotel in Paris for a couple of nights on the condition they find this painting in the Louvre.

De la Tours portrays the youthful Jesus looking at His stepfather with deep affection as Jesus holds a candle to light the work of the man who was known in His community and, for much of Jesus’ life, as His father. The painting conveys a sense of love, deep affection, peace, innocence, and purity—each a wonderful attribute of Christmas and of childhood. For me, de la Tours has captured much of what Christmas represents. He does so through the eyes of a young boy, an innocent young boy. Don’t all of us, in a way, see Christmas through the eyes of children?

Given that we most often see Christmas in this light, I am surprised at how little attention is actually paid to Jesus’ childhood. It is not just art that ignores His childhood and focuses primarily on His birth, later ministry, atoning sacrifice, and Resurrection. The scriptural story of Jesus’ earthly sojourn is also mostly silent from the flight into Egypt at around the age of two until He begins His ministry by journeying to be baptized by John in the Jordan River as a mature man, perhaps thirty years old. The notable exception is the scriptural appearance of Christ at about age twelve when the group He and His family had joined to journey from Nazareth to Jerusalem left Jerusalem for the long journey back to Nazareth without Him. Listen to the voice of Mary, who is clearly, in this instance, not the mother of Jesus the Son of God but the mother of Jesus the child, almost a teenager:

And when he was twelve years old, they went up to Jerusalem after the custom of

the feast.

And when they had fulfilled the days, as they returned, the child Jesus

tarried behind in Jerusalem; and Joseph and his mother knew not of it.

But they, supposing him to have been in the company, went a day’s

journey; and they sought him among their kinsfolk and acquaintance.

And when they found him not, they turned back to Jerusalem, seeking him.

And it came to pass, that after three days they found him in the temple. . . .

. . . and his mother said unto him, Son, why hast thou thus dealt with us?

behold, thy father and I have sought thee sorrowing. . . .

And he went down with them, and came to Nazareth, and was subject unto

them. (Luke 2:42–51)

How many of us have heard that voice in our own mothers’ expressions of concern about our being out a bit too late on a date or driving on snow-packed and icy winter roads?

Beyond this single account, we know virtually nothing else about Jesus’ life between the ages of two and thirty. Isaiah does tell us that Jesus’ childhood and young adulthood would not be easy: “Therefore the Lord himself shall give you a sign; Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel. Butter and honey shall he eat, that he may know to refuse the evil and choose the good” (Isaiah 7:14–16). “For he shall grow up before him as a tender plant, and as a root out of dry ground” (Isaiah 53:2).

“Butter,” probably better translated as “curd,” is not meant in this scripture to imply wealth or luxury but just the opposite: the harsh and difficult conditions of the poor at the time. Archaeological and other evidence suggest that life at the time was probably short—not more than forty years if a person survived early childhood. Evidence also suggests that nutrition was inadequate. However, Isaiah suggests that growing up in Jesus’ particular environment was important in forming the person who subsequently chose to take upon Himself our sins.

We know that Jesus grew up in a very small village of perhaps two hundred people, most of whom were probably part of His extended family. He was known as the son of a carpenter: “Is not this the carpenter’s son?” (Matthew 13:55) and as Joseph and Mary’s son. Mark tells us that Jesus was himself a carpenter: “Is this not the carpenter?” (Mark 6:3).

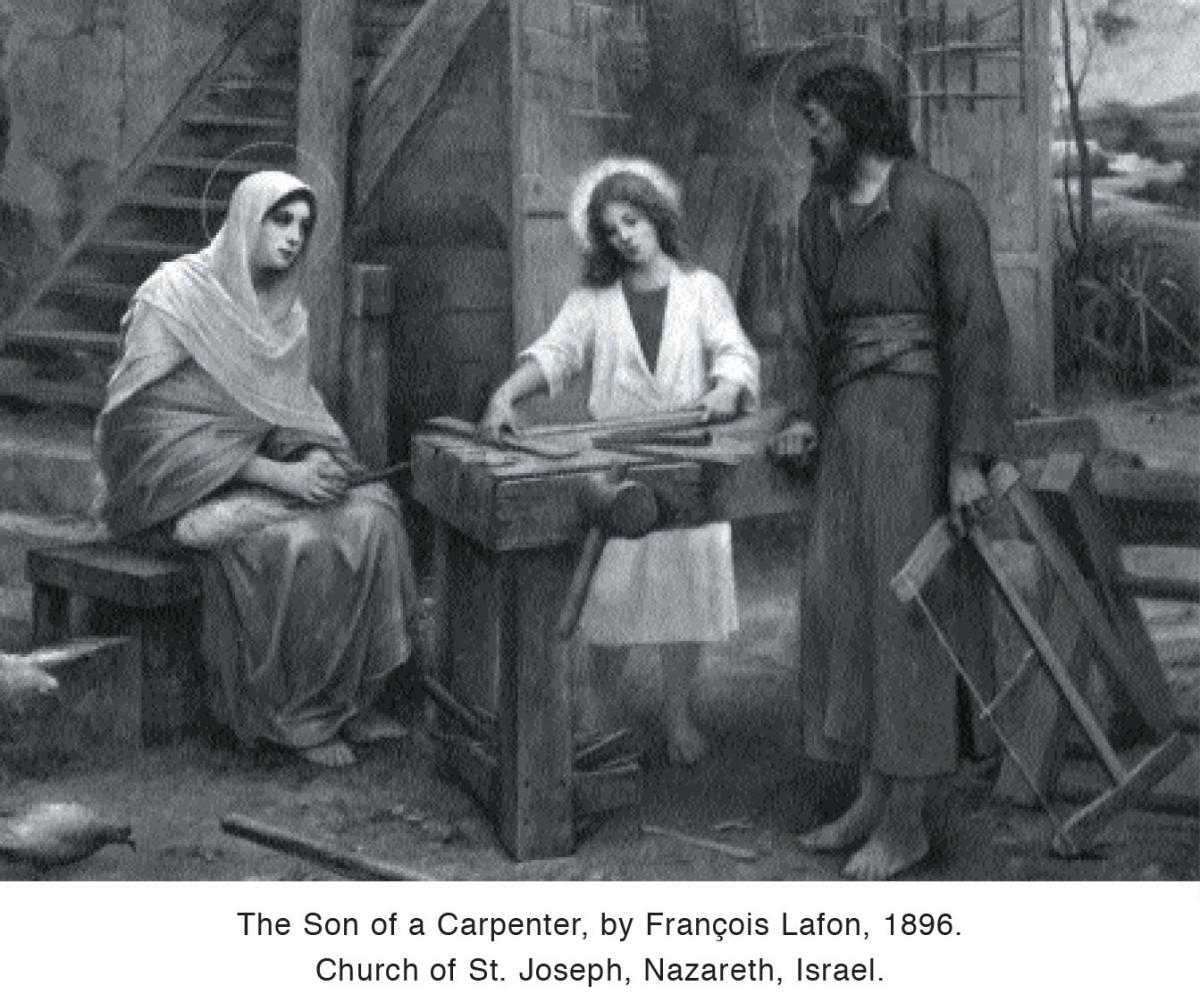

Imagine Jesus as an apprentice in Joseph’s workshop. The painting that comes to my mind at this point, one more of a few of Jesus as a child or young adult, is from St. Joseph’s Church, built over the traditional site of Joseph’s shop in Nazareth. While not as powerful as the de la Tours painting, it does convey the notion of apprenticeship and of parents gathered around and working with a maturing boy. Even in the de la Tours painting, Jesus is at work with Joseph. De la Tours has Joseph bending over with a primitive brace and bit, drilling on the dimly lit beam at his feet while Jesus shields the candle flame from any breeze as He lights his stepfather’s work.

We also know from the scriptural record that Jesus grew up in a fairly large family. Both Mark and Matthew tell us of four brothers—James, Joses, Juda, and Simon—and unnamed sisters (Mark 6:3; Matthew 13:55–56).

Finally, we can infer from the scriptural record that Jesus had affection for Nazareth, the village where He grew up. We can see this in a kind of backhanded way when, in the excitement that many of us understand about returning as an adult to our childhood home, He is disappointed and clearly very pained by His reception in Nazareth. Listen to His voice on this occasion: “And he went out from thence, and came into his own country. . . . And when the sabbath day was come, he began to teach in the synagogue: and many hearing him were astonished, saying, From whence hath this man these things? and what wisdom is this which is given unto him, that even such mighty works are wrought by his hands? . . . And they were offended at him. But Jesus said unto them, A prophet is not without honour, but in his own country, and among his own kin, and in his own house” (Mark 6:1–4).

Significantly, we know almost nothing about the period between Jesus’ birth and the beginning of His ministry thirty years later. The absence of a scriptural record is, I believe, neither an accident nor an oversight. While working through divine inspiration, Joseph Smith expanded and corrected the Bible, leaving the account of Jesus’ childhood untouched. This was not an oversight, as the Prophet clearly felt comfortable expanding, to a considerable degree, the scriptural account of Melchizedek’s life. The difference between his treatment of Melchizedek’s life and Jesus’ early life suggests that God, Jesus’ mortal father, clearly wanted His Only Begotten Son to grow up in the kind of environment typical for children and young adults of the time—protected and sheltered from the adult world He would enter, but only as an adult.

Think about it for a moment. Jesus Christ, the literal Son of God, virtually disappears from the scriptural record from the age of two to the age of thirty. What does He disappear into? He disappears into childhood, into teenage years, and into young adulthood in a small village in the hills near the Sea of Galilee, there to grow up among brothers, sisters, cousins, aunts, uncles, neighbors, and friends.

I believe that this disappearance of Jesus into childhood wasn’t by chance but happened by heavenly design. There is something so important that occurs during these formative years that our Father in Heaven wanted His Son to experience it. In other words, it was important for Jesus to be not only the Son of God but also the child of Mary and Joseph and the brother of James with other brothers and sisters around Him. Something very significant about childhood warranted this extraordinary occurrence in which the Son of God literally disappeared into childhood and did not reappear until He was an adult.

In Conan Doyle’s Silver Blaze, Watson asks Holmes, “Is there any point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

Holmes replies, “To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

Watson observes, “The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

Holmes responds, “That was the curious incident.”[1]

For Holmes, silence was a clue. Similarly, the silent scriptural record is, I believe, a clue to at least two things about Jesus’ life from age two to age thirty. First, Jesus had a protected childhood. Indeed, it remains protected in precisely the sense that we know virtually nothing about it and are clearly not supposed to. Second, Jesus had an extended childhood. If ever there was a child who could have matured quickly and assumed His divinely appointed role and mission, it is Jesus Christ, the literal Son of God. Yet, with what must be seen as great patience, His earthly and heavenly fathers allowed Jesus to mature slowly—in short, to have a childhood.

We live, unfortunately, in a world that intrudes on childhood and that wants to deprive it of innocence, charm, faith, trust, hope, and even peace and security—all the things that make childhood rich and important. We live in a world that literally wants to rob children of childhood. In doing so, the world robs them of the joy that maybe comes to children only when they are able to live protected to some degree from the world with innocence, faith, trust, and security.

Kiku Adatto, director of the Children’s Studies Program at Harvard, noted: “We’re obsessed with children, but that doesn’t mean the same thing as upholding the idea of childhood. In fact, we’re obsessed with it [children] precisely because all the barriers between childhood and adulthood are breaking down.”[2] As an example of this breakdown, Adatto’s group at Harvard studied photos of children taken throughout this century and found that children’s pictures that once paid homage to childhood innocence have increasingly given way to sexualized images of ever-younger childlike models in ads for cologne, underwear, jeans, or the like.[3]

Stephanie Coontz, author of The Way We Really Are, notes that for years, children were excluded from adult knowledge and participation in the adult world. “Now,” she says, “we try to exclude them from participation, but we’re unable to exclude them from knowledge. It’s the most pathological situation [imaginable].”[4]

Kay S. Hymowitz, who wrote “Tweens: Ten Going on Sixteen,” suggests that absentee parents—due primarily to parents working long hours away from home—and a “sexualized and glitzy media-driven marketplace” have pushed young children into settings where peer expectations encourage choices regarding dress, language, and behavior that were once confronted by young people five, six, or even ten years later.[5]

There is legitimate concern and much hand-wringing these days about a world that intrudes with adult themes and issues in our homes and in our children’s lives. I’m hardly the first to point to what appears to be an unrelenting assault on childhood. It is important that, as prophets have counseled, we fortify our homes against these intrusions—that we protect our children’s childhoods. There is much that we can and ought to do in this effort. Though it goes beyond the purpose of this essay to do more than encourage all of us in this effort, it is worth taking note of Isaiah’s counsel: “And all thy children shall be taught of the Lord; and great shall be the peace of thy children” (Isaiah 54:13).

That is a remarkable promise. If we teach our children of—that is, about—the Lord and teach them to love the scriptures and the words of prophets that testify and teach of Him, our children will have peace. Note that the promised reward of “peace” is for our children as children, not as adults, and not for us as parents, at least directly. Note also that the scripture can be read to suggest that our children will, if we create the environment, be taught by the Lord.

However, we make a mistake if we believe that it is we against the world in protecting childhood. Indeed, I want to suggest that we are often coconspirators with the world in robbing our children of their childhoods. “How so?” you might ask. My answer is that we are coconspirators because we relentlessly push our children to grow up too fast.

As noted earlier, it was not simply that Jesus had a protected childhood; He also had an extended childhood. We are aware of a world that would intrude on childhood. Are we equally aware of our own efforts to shorten childhood? Think of the stereotypical example: Little League—a game in which boys dress like men and are pushed to perform like men while their fathers stand on the sidelines and act childish. Don’t we too often give extraordinary attention to children who seem particularly precocious—that is, to those who seem particularly adult?

There is a pride, a false pride, in boasting about our children being the “youngest” to have accomplished such and such (typically adult) feats. Thus, while we bemoan the encroachment of the world into our homes, complaining that an intrusive adult world forces our children to confront adult themes and adult issues before we think they ought to, at exactly the same time, we push our children out of childhood and out of important teenage experiences. In short, we push them to act like adults, to take on adult activities, and to perform like adults well before they are adults. In doing so, we rob our children of their precious childhoods just as surely as does a world that seems hostile to childhood.

Here is an example of what I’m saying. A few years ago, I held an administrative position at Brigham Young University where I dealt with appeals from parents on admissions matters.

Among the most difficult for me were appeals from parents whose children had been denied “early admission”—that is, from those parents who believed that the proper place for their children who were fourteen, fifteen, or sixteen years old was with young adults in a university setting. The common complaint was, “There’s nothing left for them to do in high school.” On occasion, I responded, “Well, except to attend the junior prom.”

This answer, meant to be semiserious but not flippant, always drew an icy silence from the other end of the telephone line. I note, parenthetically, that I have five children. Over the past decade or so, I have had five fifteen-year-old teenagers living in my home. So I can understand the natural urge of parents, on occasion, wanting to have their teenagers somewhere else or, perhaps, anywhere else. But it’s precisely because I sometimes wanted my children somewhere else that I came to understand the realities of such thinking. Maturing takes time—even apparently for the Son of God, and the development of the attributes that really matter requires both a protected and an extended childhood.

With regard to this urge to push our children through schooling as rapidly as possible, what is it about the world of adult work that makes us so anxious to push our children into it? Do we really believe that entering the world of full-time work or embarking on a career as soon as possible results in a better life than learning about and enjoying teenage years and then entering the workforce and beginning a career in a timely fashion after high school, college, or technical training is completed?

Curiously, adults often look back with nostalgia at precisely the teenage years in their own lives and yet seem so eager to push their children quickly through this time period. Michael and Diane Medved frame this situation nicely when they suggest that a protected and extended childhood allows children the luxury to concentrate on really important things while, by contrast, adults are forced to give attention to those things that are merely urgent.[6]

The murder several years ago of seven-year-old Jon Benet Ramsey was shocking. It was shocking because no child ought to be deprived of life in that manner and at that age. But wasn’t it also shocking to see a child dressed up to effect the look of a twenty-year-old woman? Whatever one thinks of beauty pageants or contests for twenty-year-old young women, there is something deeply upsetting and disturbing about a seven-year-old child made to pretend that this is her world. Perhaps what stunned people about this tragic murder is that the photo was a caricature, or even a mirror, in which we saw something of our own efforts to force our children to grow up too quickly and before their time.

Surely, if ever a precocious child has lived on the earth, that child is Jesus Christ, the literal Son of God. Yet our Father in Heaven apparently wanted His Son to mature slowly—to enjoy childhood, teenage years, and even young adulthood, protected from an untimely entrance into the adult world. We have no evidence that He was pushed to become something before He was an adult, although surely Jesus could have been anything He wanted to be at almost any time during those years. Abundant evidence exists to show that He was protected. In fact, the lack of a scriptural record speaks eloquently, in its silence, to this fact.

Where the scriptural record does speak, it clearly suggests that He grew up. Luke records that after Jesus’ birth, the family “returned into Galilee, to their own city Nazareth. And the child grew, and waxed strong in spirit, filled with wisdom: and the grace of God was upon him” (Luke 2:39–40). Then, after the journey to Jerusalem in which Jesus was left behind and after His frantic parents searched for three days, we read that He “came to Nazareth, and was subject unto them. . . . And Jesus increased in wisdom and stature, and in favour with God and man” (Luke 2:51–52). Note that Luke’s first observation is about the period between Jesus’ birth and His appearance in the temple at about the age of twelve and that the second refers to the period after His visit to the temple—that is, the period when He would have been a teenager.

Paul observed, “Though he were a Son, yet learned he obedience by the things which he suffered”—that is, experienced (Hebrews 5:8). And from a modern text written by John and revealed to the Prophet Joseph Smith, we learn: “And I, John, saw that he received not of the fulness at the first, but received grace for grace . . . [and] continued from grace to grace, until he received a fulness; And thus he was called the Son of God” (D&C 93:12).

Joseph Smith’s inspired translation of the Bible provides some additional insight: “And it came to pass that Jesus grew up with his brethren, and waxed strong, and waited upon the Lord for the time of his ministry to come. And he served under his father, and he spake not as other men, neither could he be taught; for he needed not that any man should teach him. And after many years, the hour of his ministry drew nigh” (JST, Matthew 3:24–26).

The clear sense of these passages is that Jesus grew up by passing through a childhood and youth that were the norm for His day.

In regard to our own children’s growing up, Neil Postman, author of The Disappearance of Childhood, argues that an “adult knows about certain facets of life—its mysteries, its contradictions, its violence, its tragedies—that are not considered suitable for children to know. . . . As children move toward adulthood, we reveal these things to them.”[7] But we do so slowly and in a timely fashion. In this regard, Mitchell Kalpakgian argues that for children to become intellectually complete adults, they need “a true childhood [that] provides leisure and lightmindedness—an atmosphere of play that stimulates the creative imagination and nourishes the inner life of the mind and soul.”[8]

I don’t want to be misunderstood. We protect childhood not by nostalgic indulgence but by a recognition that while childhood exhibits attributes that are extraordinarily important and wonderful, children are also born impulsive, self-centered, and irresponsible. An important part of an extended childhood is helping children to learn to value and cooperate with others, to delay gratification, and to establish realistic connections between their behavior and its consequences. This maturing process requires both biological maturation and years of sustained parental effort. It is not easy to teach children to be considerate, empathetic, and moral or to behave ethically and with a generous heart and spirit. The crucial learning environment to develop these attributes is one that combines affection, discipline, example, emotional space, and, very importantly, time. That is to say, the crucial learning environment is an extended, as well as a protected, childhood.

I also don’t want to be thought to be Pollyannaish or naive or to be understood to be arguing that we should not prepare, in a timely way, our children for the world in which they will live. But I confess that I cringe a bit when I read or hear a public service ad that asks, “Have you talked with your child yet about sexually transmitted diseases?” or “Have you talked with your child yet about drugs and drug abuse?” Perhaps such discussions are necessary; but, if so, it’s surely a damning indictment of our age that they are. Moreover, the argument that our children are going to have to face such and such an issue at some point anyway so they may as well face it now is specious and wrongheaded. It is an argument that invariably brings adult issues and concerns into our children’s lives at earlier and earlier points. Might it not be true that precisely because our children will have to face certain specific issues at some point, they ought to be protected from those issues as children? That is, isn’t it likely that an extended and protected childhood best equips them for the world they will have to confront as adults?

The Christmas season is a wonderful season—one that gives us the opportunity to see once again what a beautiful and extraordinary world this is when seen through the eyes of children. Christmas not only is “for children” but also is a holiday in celebration of childhood. Christmas is in its transcendent meaning also a celebration of Jesus’ mission of redemption. The child who holds the candle to light the work of the father Jesus knew in Nazareth, as reflected in the de la Tours painting, becomes literally the light of the world when He enters it as an adult, fully prepared by His heavenly heritage and by a protected and extended childhood in the hills of Nazareth.

Although redemption is the central, glorious, and sublime message of Christmas, in its particulars—that is, its language—and in the memories and images that Christmas evokes, Christmas is also a celebration of childhood. I hope that at each Christmas season we may reflect on this fact and pause to think not just about how we might protect our children’s childhoods from an intrusive world but also about how we can protect our children’s childhoods from our own inclinations to push them to become something too soon.

This wonderful season gives us the opportunity to see, once again, what a beautiful and extraordinary world we live in when it is seen through the eyes of children. I pray that, whatever our age, we might seek to see it in this way, at any time of the year, and that we might rejoice in those attributes that make children, as children, so special.

Notes

[1] Arthur Conan Doyle, “Silver Blaze,” Sherlock Holmes’ Greatest Cases (New York: Franklin Watts, 1967), 423.

[2] Peter Applebome, “No Room for Children in a World of Little Adults,” New York Times, 10 May 1998, 9.

[3] Ibid., 10.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Kay S. Hymowitz, “Kids Today Are Growing Up Way Too Fast,” Wall Street Journal, 28 October 1998, A22.

[6] Michael Medved and Diane Medved, Saving Childhood (New York: HarperCollins, 1998).

[7] Neil Postman, The Disappearance of Childhood (New York: Vintage, 1994), 15.

[8] Mitchell Kalpakgian, “Why the Entertainment Industry Is Bad for Children,” New Oxford Review 63, no. 2 (March 1996): 14.