Questions in the Book of Mormon

Holt Zaugg

Holt Zaugg, "Questions in the Book of Mormon," Religious Educator 19, no. 1 (2018): 83–101.

Holt Zaugg (holt_zaugg@byu.edu) is the assessment librarian at the Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University.

Questions are the catalyst that drives learning, providing a focus on what an individual wants or needs to know. They are the drivers that move knowledge acquisition to realms of greater understanding and wisdom. Karen Brown, a professor at Dominican University, describes questions as the heart of learning and the impetus for building knowledge.[1] Teachers and students use questions to vet information and allow them to develop the ability to see when change is coming and to manage changes when they occur. Questions help people to zone in on important details that help to sharpen and refine their thinking.

Individual Use of Questions

Individuals use questions to clarify their current understanding and to move towards new wisdom. Questions enable them to combine content—their personal experience and the world’s wisdom, including the experiences of others—and do it in a way that enables them to think more critically.[2] As students ask questions, they take greater control of their learning and allow for greater discovery and engaged learning.[3] However, it is not enough to ask more questions. It becomes imperative that students slow down and learn to ask better questions—ones that steer the conversations towards the problems they are seeking to understand and solve.[4] At times teachers need to help direct students in the type of questions they ask.

Teacher Use of Questions

Teachers use questions to guide learning towards a targeted goal, seeking to help individuals gain greater knowledge, understanding, and wisdom. In addition to asking questions for students to restate facts and figures, a teacher can pose questions that become the framework wherein instruction and learning guide students to deeper understandings.[5] Teachers can use questions to facilitate student learning and nurture them as they start to ask meaningful questions that engage their higher thinking process and that facilitate learning.[6] When discussing historical material, teachers can ask questions that challenge students to think about the past and that assist them in gathering evidence, a process that will help students in their search for patterns across time.[7] Such activities help students simultaneously think broadly and deeply.

Book of Mormon Questions

One of the challenges members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints face is how questions may be used to better identify issues challenging one’s faith and the doctrines of the Church. Fortunately, questions in the Book of Mormon provide insights on how questions were used to increase gospel understanding and personal faith. Identifying the different types of questions in the Book of Mormon and how these questions were used enables gospel instructors and students to use questions more effectively. The patterns shown in the Book of Mormon highlight how questions can be used as tools to increase one’s knowledge, understanding, and wisdom through instruction, application, and growth activities.

In the Book of Mormon, conversations between prophets or leaders and others become instructive as examples of the interplay between questions and answers. The way the prophets, leaders, or learners use questions becomes a hallmark of how learning is advanced. Questions become a driving force for teaching (providing instruction), collaboration (seeking learning), and confrontation (arguing opposite views). Examination of Book of Mormon conversations to understand the interplay of questions and answers in specific contexts provides us with further insights into how we may use questions to guide learning and increase understanding. Insights into the interplay between questions and answers help us prepare to better use questions in a variety of settings.

As a teacher and a learner, I used this exploration of questions within the Book of Mormon to improve my understanding and use of questions in everyday contexts. I sought to understand what questions are found in the Book of Mormon, how they are used in conversations, and, most importantly, how they may be integrated into my teaching and personal learning. Hopefully, my journey will facilitate others wishing to improve their use of questions to further their acquisition of knowledge, understanding, and wisdom.

Method

In beginning this personal study, two key issues needed to be resolved before I could begin. First, what constitutes a question within the Book of Mormon? Second, what categories should be used to define the types of questions used?

What Is a Question?

As to the first question, much of the original handwritten text of the Book of Mormon was written without punctuation. In fact, most of the current punctuation used in the Book of Mormon was added while the manuscript was being set for print.[8] Rather than take issue with what could or should be considered a question, I used a pragmatic approach. I accessed the online version of the Book of Mormon, available at scriptures.lds.org, and copied the entire contents into a word-processing document. Then, using the question mark as a search term, I flagged every instance where a question occurred. The question mark, as it currently occurs in the Book of Mormon, designated questions for my purposes.

Once identified, each specific question and its corresponding scriptural reference were organized in one of three ways: first, if a single question was found in a single verse; second, if the question spanned several verses; or third, if several questions were asked in a single verse. To keep track of the scriptural reference, when a verse contained more than one scripture, each question was separated from the other questions, and the scriptural reference remained the same. When the question spanned several verses, all verse references were included. In some cases, text that is not part of the question occurs before or after a question in a verse. This text often provides context to the question or the conversation. As a result, any nonquestion text associated with any question, regardless of where the question occurred, was included to help provide a context in my analysis. Coding examples are shown in figure 1. After identifying all questions within the Book of Mormon, I also counted the total number of questions in each book of the Book of Mormon.

Multiple verses for one question | Mosiah 12:20–24 | 20 And it came to pass that one of them said unto him: What meaneth the words which are written, and which have been taught by our fathers, saying: 21 How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings; that publisheth peace; that bringeth good tidings of good; that publisheth salvation; that saith unto Zion, Thy God reigneth; 22 Thy watchmen shall lift up the voice; with the voice together shall they sing; for they shall see eye to eye when the Lord shall bring again Zion; 23 Break forth into joy; sing together ye waste places of Jerusalem; for the Lord hath comforted his people, he hath redeemed Jerusalem; 24 The Lord hath made bare his holy arm in the eyes of all the nations, and all the ends of the earth shall see the salvation of our God? |

Text after question | Alma 60:18 | 18 But why should I say much concerning this matter? For we know not but what ye yourselves are seeking for authority. We know not but what ye are also traitors to your country. |

Text before question | 3 Nephi 13:25 | 25 And now it came to pass that when Jesus had spoken these words he looked upon the twelve whom he had chosen, and said unto them: Remember the words which I have spoken. For behold, ye are they whom I have chosen to minister unto this people. Therefore I say unto you, take no thought for your life, what ye shall eat, or what ye shall drink; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on. Is not the life more than meat, and the body than raiment? |

Multiple questions in one verse | Alma 60:20 | 20 Have ye forgotten the commandments of the Lord your God? |

Alma 60:20 | Yea, have ye forgotten the captivity of our fathers? | |

Alma 60:20 | Have ye forgotten the many times we have been delivered out of the hands of our enemies? |

Figure 1. Example of identification of questions in the Book of Mormon.

How to Categorize Questions?

At this point the second question was addressed, namely how to code the questions. Background research indicated several methods were possible using either traditional categories described in the literature or very personal categories—ones that met personal understandings and needs. Questions may be coded by interrogative words such as who, what, where, when, why, how, and by questions beginning with verbs.[9] This type of categorization places questions in categories that indicate the type of responses they expect to elicit; that is, would the questions elicit a more open-ended response (who, what, where, when, why, and how), or would the reply be an alternate response, one of two possible answers?

Following this thought process, I undertook a second analysis of question types. Categories for this section proved more problematic, as there are many ways to categorize questions. Brown identified eight types of essential questions used in library instruction to help students vet and better understand the sources they were using.[10] Lustick, in discussing how questions may be used in science instruction, identified four categories for questions by the type of response that may be given;[11] they ranged from recalling information in increasing levels of detail to more open-ended questions used to sustain reasoning and inquiry. VanTassel-Baska also created four categories of questions; these questions asked gifted students to recall, narrow, expand, or evaluate in their response.[12] Pohlmann and Thomas categorized questions used in conversations by four types.[13] These sought to clarify, explore, dig deeper, and raise broader issues.

The categorization of questions may take many forms. The point of categorizing is that the categories used are helpful to the people (teachers or students) asking the questions. Categories help ensure that teachers and students do not repeatedly use a single type of question but instead use a variety of questions to further their purpose.

Personal Learning Model

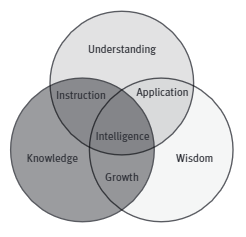

In figure 2, I used a personal learning model to categorize questions. Briefly summarized, the categorization has three spheres (knowledge, understanding, and wisdom) that are connected to three pathways (instruction, application, and growth), with the ultimate goal of leading to intelligence, or light and truth. Each of these categories is briefly described.

Figure 2. Learning model used to code questions.

Figure 2. Learning model used to code questions.

Knowledge. This sphere refers to the gathering of data (facts, numbers, etc.), and questions posed here ask for a recall of this data.

Understanding. This sphere refers to the organization and connection of new and past data. Questions seek to help individuals understand how new knowledge connects to their current knowledge.

Wisdom. This sphere contains the “aha” moment when learners see how they can act upon their knowledge and understanding in the world in which they live. These questions expand the learners’ capacity to expand and connect their current learning.

Instruction. This connector includes the formal and informal processes that allow for the ebb and flow between knowledge and understanding. Teachers use questions to guide learners between these two spheres. Questions used here by learners indicate a self-directed nature.

Application. Questions in this connector help one (as a learner and a teacher) to apply the networks and connections made in understanding real-world situations. Questions in this area help one to convert knowledge and understanding into actions.

Growth. Questions in this area facilitate the development of a new awareness. They help complete the circle back to knowledge and can lead to the creation or discovery of new knowledge.

As my personal learning model, this categorization helps me to understand what types of questions were used in the Book of Mormon. It furthers my understanding of how the questions were used and enables my ability to use them in my life and teaching.

In summary, I categorized and organized questions in the Book of Mormon in the following ways:

- I identified all questions in the Book of Mormon by using a question mark and included surrounding scripture to aid the context of the question.

- I counted the total number of questions found in each book of the Book of Mormon. I determined the percent of questions in each book by dividing the number of questions in each book by the total verses in each book.

- I identified the key words in each question—that is, a word that indicates what the question is seeking. Often it is a verb (e.g., is, was, know), but other words are also used to define the emphasis of the question (e.g., what).

- Using the previous identification, I coded each question by the type of answer expected. This includes alternate-response questions, allowing for one of two possible responses (e.g., yes-no or will-won’t), or open-ended questions, allowing for multiple answers (e.g., who, what, where, why).

- Finally, using my personal learning model, I coded each question into categories identifying what the question was seeking to elicit (i.e., knowledge, understanding, wisdom, instruction, application, growth, and intelligence).

As this was a personal journey with questions in the Book of Mormon, only I made each coding. Others examining questions found in the Book of Mormon may code questions differently. A more rigorous examination would use multiple coders.

Questions in Conversations

During this coding process, I noticed that many questions were part of conversations between two or more people, typically housed within a single Book of Mormon story. Since I also wanted a more personal understanding of how questions are used, I identified specific conversations in the Book of Mormon. Using these conversations, I examined the interplay of questions and answers to determine how questions were used in conversations. Although there are other conversations in the Book of Mormon, I chose these particular ones for their personal appeal and because I felt they were representative samples of all Book of Mormon conversations. The conversations and their location in the Book of Mormon are shown in table 1.

Table 1. Selected Book of Mormon Conversations

Location | Conversation |

| Jacob 5 | The allegory of the tame and wild olive trees |

| Mosiah 12–16 | Abinadi teaching King Noah and his court |

| Alma 11–12 | Alma and Amulek’s contention with unbelievers in Ammonihah |

| Alma 18 | Ammon teaching King Lamoni |

| Alma 22 | Aaron teaching Lamoni’s father |

| Alma 26 | Ammon glorying in the power of the Lord near the end of his mission to the Lamanites |

| Alma 30 | Korihor’s conversation with Alma the Younger |

| Alma 60–61 | Moroni’s letter to Pahoran, and Pahoran’s response |

| 3 Nephi 13 | Jesus teaching the Nephites |

| Mormon 9 | Moroni teaching those who do not believe in Christ, gifts, miracles, and signs |

The conversations were grouped into three broad categories: monologues, collaborative dialogues, and confrontational dialogues. Using these categorizations, the conversations were examined to determine the role questions played in teaching and learning.

Findings

I identified 545 questions in the Book of Mormon (see table 2). Approximately 8 percent of the Book of Mormon verses contain questions, but this is an estimate, as some verses have more than one question and some questions are asked across more than one verse. Within each book of the Book of Mormon, the questions-to-verses ratio ranges from a low of 0 to a high of 13 percent. Approximately half (46 percent) of the questions occur in the first part of the Book of Mormon, written from the small plates, which was used to replace the lost 116 pages. Only two questions in total were asked in the books of Jarom, Omni, and the Words of Mormon. The book of Jarom appears to have a large percent of questions, but this is due to the low number of total verses. Most questions are asked in books associated with teaching or confrontations—namely 1 Nephi, 2 Nephi, Alma, and Mosiah.

Table 2. Percentage of Questions in the Book of Mormon by Verses per Book

| Book | Verses | Questions | Percent |

| 1 Nephi | 618 | 52 | 8% |

| 2 Nephi | 779 | 74 | 9% |

| Jacob | 203 | 25 | 12% |

| Enos | 27 | 1 | 4% |

| Jarom | 15 | 2 | 13% |

| Omni | 30 | 0 | 0% |

| Words of Mormon | 18 | 0 | 0% |

| Mosiah | 785 | 55 | 7% |

| Alma | 1,975 | 213 | 11% |

| Helaman | 497 | 33 | 7% |

| 3 Nephi | 785 | 38 | 5% |

| 4 Nephi | 49 | 1 | 2% |

| Mormon | 227 | 26 | 11% |

| Ether | 433 | 14 | 3% |

| Moroni | 163 | 11 | 7% |

| Total | 6,604 | 545 | 8% |

Types of questions were also separated into two categories: open ended and alternate response (see table 3). About half of all questions are open ended (46 percent). Of interest is that not one when question is found in the Book of Mormon. What questions dominate the open-ended type of questions. Dominant alternate-response questions are split between do, will, and have. It should also be noted that the older forms of words found in the Book of Mormon have been altered to current English: for example, knowest has been changed to know.

Table 3. Type of Questions in the Book of Mormon

Open Ended | Alternate Response | ||

| Type | Amount | Type | Amount |

| Who | 51 | Are | 24 |

| What | 75 | Believe | 17 |

| Where | 22 | Can | 18 |

| When | 0 | Could | 3 |

| Why | 56 | Deny | 1 |

| How | 47 | Did | 7 |

| Which | 1 | Do | 49 |

| Does | 1 | ||

| Has | 12 | ||

| Have | 40 | ||

| Is | 32 | ||

| Know | 16 | ||

| May | 1 | ||

| Remember | 2 | ||

| Shall | 11 | ||

| Should | 4 | ||

| Suppose | 1 | ||

| Was | 3 | ||

| Were | 2 | ||

| Will | 44 | ||

| Would | 5 | ||

| Open Total | 252 | Alternate Total | 293 |

| Grand Total | 545 | ||

Types of Conversations

As mentioned earlier, I identified ten conversations to examine the interplay of questions and answers or instruction. Those conversations fall into one of three broad categories of conversations: monologues, collaborative dialogues, and confrontational dialogues. For my purposes here, monologues are defined as one speaker with others listening or reading; letters are considered to be monologues of instruction or teaching. The collaborative- and confrontational-dialogue categories are characterized by a conversation between two or more people, typically with others listening to the exchange. In collaborative dialogues, one dialogue participant is seeking to gain greater knowledge or understanding from the other. In confrontational dialogues, the participants are speaking on opposite sides of an issue. In one instance (Alma and Amulek conversing with Zeezrom in Ammonihah), the conversation begins as a confrontational dialogue but switches to collaborative elements after Zeezrom begins to have a change of heart. The placement of conversations within the three categories is shown in table 4.

Table 4. Placement of Conversations within Three Categories

Monologues | Collaborative Dialogue | Confrontational Dialogue |

| Alma 26: Ammon glorying in the power of the Lord near the end of his mission to the Lamanites | Jacob 5: The allegory of the tame and wild olive trees | Mosiah 12–16: Abinadi teaching King Noah and his court |

| Alma 60–61: Moroni’s letter to Pahoran, and Pahoran’s response | Alma 11–12: Alma and Amulek’s contention with unbelievers in Ammonihah* | Alma 11–12: Alma and Amulek’s contention with unbelievers in Ammonihah* |

| 3 Nephi 13: Jesus teaching the Nephites | Alma 18: Ammon teaching King Lamoni | Alma 30: Korihor’s conversation with Alma the Younger |

| Mormon 9: Moroni teaching those who do not believe in Christ, gifts, miracles, and signs | Alma 22: Aaron teaching Lamoni’s father |

* This conversation switches between a confrontational and a collaborative dialogue.

Since I was more concerned with how questions are used in instruction, little of the content of the conversation is discussed here. Rather, I examine how questions are used to introduce or frame the encounter. The focus is placed on where and how the questions are used during the actual conversation, especially focusing on instruction or learning.

Types of Questions

Four types of questions are found within my study—determining questions, which seek to determine the learner’s knowledge and understanding; focusing questions, which seek to focus the learner’s attention; accountability questions, which seek to hold individuals or groups accountable for their actions; and reflection questions, which seek to encourage personal reflection. While any of the types of questions may be used in any conversation category, some are better suited to one type of category over another.

Determining Questions

These questions seek to determine what the listener knows and understands. They are used in both collaborative and confrontational conversations. The questions are typically alternate responses (e.g., yes-no, will-won’t) in which the speaker seeks to determine what the listener understands. They serve to determine the learner’s commitment to or understanding of some assertion.[14]

Examples include Zeezrom’s conversation with Amulek (Alma 11 and 12), the instruction of Lamoni (Alma 18) and his father (Alma 22), and Korihor’s defense in front of the judges (Alma 30). One question found in all of these conversations, in one form or another, is “Believest thou that there is a God?” (Alma 11:24; 18:24; 22:7; 30:37). The determining questions seek to establish the extent of the listener’s knowledge, understanding, commitment, and experience—they mark a starting point for instruction and help the teacher build on what the learner already knows. The questions help the teacher make connections to the learner’s understanding and experiences. In confrontational situations, they also help to establish what the learner knows and what he or she can be held accountable for. The questions are typically a blend of alternate responses (e.g., yes-no, do-don’t) and open-ended questions, allowing for greater elaboration in a response.

In addition to the purpose of discovering one participant’s current knowledge and understanding, determining questions are used to gain and build trust between teachers and learners in collaborative conversations. An example is the instruction of Lamoni and his father. Ammon helps Lamoni by identifying his “marvelings.” Ammon’s actions with Lamoni’s sheep, along with Lamoni’s inquiring if Ammon was the Great Spirit, open up an exchange between the two in which Lamoni explores and decides just how much he will trust Ammon. The questions in this encounter also serve the purpose of building trust and establishing a relationship between the two that initiates and facilitates the instruction.

This pattern repeats with Aaron teaching Lamoni’s father, but the pattern is accelerated no doubt because of the previous interactions between Lamoni, Ammon, and Lamoni’s father. In all likelihood, discussion between Ammon, Lamoni, and Aaron regarding this previous encounter and other experiences also prepared Aaron for his conversation with Lamoni’s father. Trust, previously gained with Ammon, was quickly transferred to Aaron as the new teacher. Lamoni’s father had, in all probability, given considerable thought to his experience with Ammon and his son. With the transfer of trust, Lamoni’s father began to ask questions to augment his knowledge and understanding. While he asked only a few questions prior to Aaron’s instruction, it is likely that, given the volume of instruction, other questions were asked to help complete his knowledge and understanding.

A teacher typically uses determining questions at the start of the instruction. The questions help the teacher to understand the student before seeking to have the student understand what is being taught. They require the learner to commit to specific assertions that define his or her knowledge, understanding, and wisdom. They are also used to form trust between teacher and learner so that the learner’s answers or questions will be treated with respect. While this trust may be transferred from one teacher to another, the trust formed must be maintained and built upon. Determining questions provide foundations upon which other questions and instruction may be built.

Focusing Questions

Both open-ended and alternate-response questions are used as focusing questions. Often the pattern includes asking one or several questions prior to instruction. The question focuses the learner’s attention on the topic of instruction. The teacher often initiates instruction with focusing questions to set the parameters of instruction. The learner will use focusing questions to expand knowledge and understanding or to fill in gaps. Teachers use questions to further their goals and interests and to help the learner gain control of knowledge and integrate it into his or her understanding.[15] The dialogue often repeats the question-instruction pattern because the instruction increases the knowledge and understanding of the listener. The question’s primary purpose is to focus attention. It should be noted that the focus questions may extend a line of thought that is beneficial to the listener by stimulating interest.

An illustration of focusing questions is found in Mormon’s final epistle to future generations (Mormon 9). In verses 2 and 3, Mormon asks several alternate-response questions (yes-no) of those who will be reading his epistle. He sets the parameters for individuals who have abandoned or questioned their faith to the point of forgetting what they know. The questions serve as a personal evaluation of what they do or do not know or believe. Mormon’s epistle continues with questions, followed by instruction. The questions serve both a reflective and forward-focusing process. The readers of the epistle reflect on where they stand in terms of knowledge and understanding of God. The forward-focusing occurs in setting the parameters for the next piece of instruction. Each question helps to build on the previous instruction by directing the reader to the next instruction framework.

Ammon uses focusing questions in Alma 26 to center his recollection of the blessings of their mission experience among the Lamanites (e.g., “What great blessings has he bestowed upon us? Can ye tell?”). The questions provide the framework for his teaching on how God provided for him and his companions in their missionary labors; these questions also acknowledge God’s hand in the missionaries’ actions. The questions guide Ammon’s comments. While the discussion is reflective in nature, as it recounts the missionary labors, it is also prescriptive, seeking to teach those undertaking similar ventures to trust in God. The questions appear as guideposts in this discussion highlighting specific points Ammon wishes to make.

The conversation in Alma 11 and 12 also illustrates this pattern. After Amulek and Alma refute Zeezrom’s initial attempt to discredit them, both Zeezrom and Antionah, a chief ruler, ask questions that guide the conversation, first with Amulek and then Alma. Although the initial intent of the questions was to discredit Amulek and Alma, the questions end up providing a focus for those listening, preparing them for the next piece of instruction. In the case of Zeezrom, the questions turn from confrontational to collaborative as he evaluates himself based on the questions asked and has a change of heart.

Two particular cases occur with focusing questions. The first comes with Korihor’s defense. In this example, Korihor uses focusing questions to instruct, but he frames the questions with leading statements that influence how the question may be answered. An example of this is in Alma 30:14–15, where, referring to prophecies, Korihor prefaces the question “How do ye know of their surety?” with “Behold, they are foolish traditions” to manipulate the response, drawing out an answer he wants instead of seeking an open, honest one. The preamble influences and directs the listener to doubt and distrust. It illustrates how comments framing the questions serve as catalysts to accentuate one response over another.

The other particular case occurs in Christ’s instruction in 3 Nephi 13. In this chapter, Christ provides instruction regarding the conduct of those serving God. The half-dozen questions at the end of the instruction serve the dual purpose of causing listeners to refocus their attention to what they should have gained from the instruction as well as to propel them to action. In this case, the focusing questions cause learners to reflect on the learning that has just taken place, before directing them to move forward in faith.

Teachers can implement focusing questions to help set the framework of the instruction as they guide learners to reflect and build upon previous knowledge and understanding. The focus questions can be used throughout the instruction in segments that lead and guide learners or as summary questions to provide a reflection on the instruction that not only reinforces the instruction but also motivates the listener to action. A caution with focusing questions—questions should openly move learners towards greater knowledge and understanding and avoid using provisos that influence their answers. A leading statement, as used by Korihor, may restrict the learners’ understanding or cause them to examine questions in only a limited context, often restricting knowledge and understanding.

Accountability Questions

These questions cause the learner to give an accountability of actions. Although somewhat reflective in nature, they primarily seek to make the listener accountable for his or her actions. Korihor before the chief judges, Abinadi teaching Noah’s priests, and Moroni’s chastisement of Pahoran are classic examples of how these questions are used. Examples of questions holding people accountable for their comments and actions include the following: “Why sayest thou that we preach unto this people to get gain, when thou, of thyself, knowest that we receive no gain?” (Alma 30:35); “If ye teach the law of Moses why do ye not keep it?” (Mosiah 12:29); “Have ye forgotten the commandments of the Lord your God?” (Alma 60:20). Each of these questions is used by the teacher to hold the listener accountable. The questions serve as a check by asking the learners to reflect on their duties and responsibilities, given the students’ level of learning and understanding or their position held.

While reflective in nature, the accountability questions are not always used to elicit reflection—many are often used in a rhetorical manner. In these cases, the questions demand accountability but also focus the listener on instruction of the duties or understanding he or she should have and exemplify.[16] Abinadi’s discourse in Mosiah 11–17 with King Noah and his priests is an example in which many accountability questions are asked but few are answered. The questions cause both reflection and accountability. The unanswered questions also frame the instruction Abinadi provides. The instruction and reflective questions combine in a dual purpose of accountability and instruction. In the case of the wicked priest Alma, the combination of accountability and instruction leads to a change in heart, resulting in him becoming a righteous prophet.

It is noteworthy that the response by those being held accountable often deflects accountability by not answering or by providing evasive answers, instead of responding with open and forthright answers. Noah’s wicked priests exemplify the former, while Pahoran’s response to Moroni’s epistles illustrates the latter.

Teachers can utilize accountability questions to cause the listener to reflect and to frame the conversation. While accountability questions can help listeners to recognize failings or help provide open account of actions, they also promote the opportunity for a backlash through denial or nonanswers. Accountability questions are often asked by someone with real authority seeking a report of action or inaction. The accountability questions often lead to swift action, as listeners either openly explain actions and move forward to greater understanding or avoid accountability through nonanswers or denials and seek retribution on the one asking for accountability.

Reflection Questions

Personal reflection occurs as the teacher attempts to promote a change in listeners through reflection. In many cases, the reflective questions are also accountability questions, as the call to accountability causes listeners to reflect on what they have done and should be doing. These queries become critical questions as they help learners to think broadly and deeply and as students search for and discover patterns from their life.[17] The ensuing personal feedback becomes a learning experience whereby the learner has the opportunity to create new understandings that lead to wisdom in changing their actions.[18] In Mosiah 12, Abinadi repeatedly uses reflection questions to encourage the judges to personally think deeply on their dereliction of duty (e.g., “If ye teach the law of Moses why do ye not keep it? Why do ye set your hearts upon riches?”). He also uses reflective questions to hold the priests accountable for not fulfilling their duty and to prompt them to reflect on what they need to be doing.

As with accountability questions, it is evident that reflective questions are not always effective in causing a change in people. In the Mosiah 12 example, only one of the judges, Alma, responded to the reflective question in a way that caused a permanent change. The learning (or lack thereof) in this situation did not depend solely on the questions used but also relied on the learner’s disposition. Only a single wicked priest used the opportunity to reflect on his actions and to make changes in his life.

A less antagonistic encounter using reflective questions is illustrated by the missionary labors of Aaron to Lamoni’s father in Alma 22. In this instance, the reflective questions facilitate the instruction and propel Lamoni’s father to ask two reflective questions: “What shall I do that I may have this eternal life of which thou hast spoken? Yea, what shall I do that I may be born of God, having this wicked spirit rooted out of my breast, and received his Spirit, that I may be filled with joy, that I may not be cast off at the last day?” (Alma 22:15). Unlike Noah’s priests, Lamoni’s father internalized the questions. He moved from gaining knowledge and understanding to applying his understanding, which led him to gain wisdom that led to light and truth. The reflective questions became generators of additional learning to direct his actions.

This use of questions also occurs in the parable of the tame olive tree by Zenos, found in Jacob 5. All of the questions asked by the Lord of the vineyard or his servant, save one, are reflective and open ended. In fact, half of all the questions reflect a desire to gain wisdom by reviewing how knowledge and understanding can be applied to the task at hand. These questions are exemplified by the self-reflective question “What could I have done more for my vineyard?” (Jacob 5:41, 49). By reviewing past applications of knowledge and understanding, the questions become forward-looking catalysts for action. The implication of “What more could I do?” not only causes the learner to reflect and evaluate what was done but also commits the learner to apply this new understanding to take action. Forms of this question are repeatedly asked, which indicates that questions used in this context and at this level become a catalyst for learning, adding to the learner’s framework of knowledge, understanding, and wisdom and leading to greater intelligence, or light and truth. Ultimately, the questions cause students to reflect on instruction, to make connections to their previous learning and experience, and to move forward towards light and truth. These questions become learning generators in that the listener, through reflection, moves forward at a pace suited to his or her needs and efforts.

Conclusion

A review of the questions found in the Book of Mormon provides guidance on the types of questions used to direct instruction and increase knowledge and understanding. The questions help to build relationships of trust through identifying background information and learning. This trust enables teachers to scaffold instruction, adding to the framework of the learner’s understanding.

For the learner, questions focus his or her attention on instruction. The learner is primed for the new instruction by the questions. Focusing questions zoom in on specific information being taught. Of note in this instance is that comments surrounding the question can bias or influence learning towards the position of the teacher instead of enabling the search for light and truth. A second variant type of focusing question is used as a summative tool to help students reflect back on the instruction and how the instruction will guide their future actions.

A third type of question holds learners accountable for actions they did or did not do. Sometimes adversarial in nature, these questions seek to expose someone’s actions and to cause him or her to commit to a given stance. Depending on the nature of the learner, these questions will assist or condemn the listener. For those who are prideful (e.g., Noah and his priests), these questions expose what they could and should be doing and condemn them for inaction. When received in humility (e.g., Alma or Pahoran), the questions cause reflection and a change to better actions by the listener.

Finally, reflective questions help the learner build upon a learning framework and help motivate towards improved actions. Reflective questions initiated by the learner are self-evaluative and cause the learner to determine what else he or she could do or should stop doing. This process serves to move the learner to a position of self-sustaining learning that leads to increased knowledge, understanding, and wisdom.

Understanding what questions are used in the Book of Mormon and how they are used to influence instruction enables readers to use questions to maximize instruction and learning. My journey of examining questions in the Book of Mormon caused me to repeatedly ask the questions “What next?” or “What else is there?” Focusing on the Book of Mormon questions caused me to internalize the questions and to advance my understanding and wisdom through better use of questions. As each person identifies questions in the Book of Mormon, understands how they are used, and internalizes them, the questions will help to increase his or her knowledge, understanding, and wisdom.

Notes

[1] Karen B. Brown, “Seeking Questions, Not Answers: The Potential of Inquiry-Based Approaches to Teaching Library and Information Science and Information Science Seeking,” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science 53, no. 3 (2016): 189–99.

[2] Leila Christenbury and Patricia P. Kelly, Questioning: A Path to Critical Thinking (Urbana: IL: ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading and Communication Skills, 1983), http://

[3] Courtney Crappell, “Fine Tuning Our Questions to Engage Modern Students,” American Music Teacher 64, no. 5 (2015): 9–12; Thomas A. Davis, “Connecting Students to Content: Student-Generated Questions,” Bioscene: Journal of College Biology Teaching 39, no. 2 (2013): 32–34;

L. Goodman and G. Berntson, “The Art of Asking Questions: Using Directed Inquiry in the Classroom,” The American Biology Teacher 62, no. 7 (2000): 473–76.

[4] Tom Pohlmann and Neethi Mary Thomas, “The Art of Asking Questions,” Harvard Business Review, 27 March 2015, 2–5.

[5] Nancy Dewald, “Web-Based Library Instruction: What Is Good Pedagogy?,” Information Technology and Libraries 18, no. 1 (1999): 26–31; Raymond C. Jones, “The ‘Why’ of Class Participation,” College Teaching 56, no. 1 (2008): 59–62; Felix Kapp, Antje Proske, Susanne Narciss, and Hermann Körndle, “Distributing vs. Blocking Learning Questions in a Web-Based Learning Environment,” Journal of Educational Computing Research 51, no. 4 (2015): 397–416.

[6] Molly Ness, “When Readers Ask Questions: Inquiry-Based Reading Instruction,” Reading Teacher 70, no. 2 (2016): 189–96; Kian Keong Aloysius Ong, Christina Eugene Hart, and Poh Keong Chen, “Promoting Higher-Order Thinking through Teacher Questioning: A Case Study of a Singapore Science Classroom,” New Waves Educational Research & Development 19, no. 1 (2016): 1–19.

[7] Kathryn M. Obenchain, Angela Orr, and Susan H. Davis, “The Past as a Puzzle: How Essential Questions Can Piece Together a Meaningful Investigation of History,” The Social Studies 102, no. 5 (2011): 190–99.

[8] Royal Skousen, “Worthy of Another Look: John Gilbert’s 1892 Account of the 1830 Printing of the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 21, no. 2 (2012): 58–72.

[9] L. Goodman and G. Berntson, “The Art of Asking Questions: Using Directed Inquiry in the Classroom,” The American Biology Teacher 62, no. 7 (2000): 473–76.

[10] Karen B. Brown, “Seeking Questions, Not Answers: The Potential of Inquiry-Based Approaches to Teaching Library and Information Science and Information Science Seeking,” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science 53, no. 3 (2016): 189–99.

[11] David Lustick, “The Priority of the Question: Focus Questions for Sustained Reasoning in Science,” Journal of Science Teacher Education 21, no. 5 (2010): 495–511.

[12] Joyce VanTassel-Baska, “Curriculum Issues,” Gifted Child Today 36, no. 1 (2013): 71–75.

[13] Tom Pohlmann and Neethi Mary Thomas, “The Art of Asking Questions,” Harvard Business Review, 27 March 2015, 2–5.

[14] Hansun Zhang Waring, “Yes-No Questions that Convey a Critical Stance in the Language Classroom,” Language & Education: An International Journal 26, no. 5 (2012): 451–69.

[15] John Lubans Jr., Patricia Dewdney, and Catherine Ross, “Library Literacy,” RQ 25, no. 4 (1986): 451–54; Ashwin Ram, “A Theory of Questions and Question Asking,” Journal of the Learning Sciences 1, no. 3 (1991): 273–318; Philip G. Smith, “The Art of Asking Questions,” The Reading Teacher 15, no. 1 (2016): 3–7.

[16] Hansun Zhang Waring, “Yes-No Questions that Convey a Critical Stance in the Language Classroom,” Language & Education: An International Journal 26, no. 5 (2012): 451–69.

[17] Kathryn M. Obenchain, Angela Orr, and Susan H. Davis, “The Past as a Puzzle: How Essential Questions Can Piece Together a Meaningful Investigation of History,” Social Studies 102, no. 5 (2011): 190–99.

[18] Helena Pedrosa-de-Jesus and Mike Watts, “Managing Affect in Learners’ Questions in Undergraduate Science,” Studies in Higher Education 39, no. 1 (2012): 1–15.