Seminary and Institute Recognition Pins

Dennis A. Wright and Alan L. Morrell

Dennis A. Wright and Alan L. Morrell, "Seminary and Institute Recognition Pins," Religious Educator 18, no. 3 (2018): 95–115.

Dennis A. Wright (dennisalbertwright@gmail.com) was a professor emeritus of Church history and doctrine, BYU when this article was published.

Alan L. Morrell (Alan.Morrell@ldschurch.org) was the artifacts curator at the Church History Museum in Salt Lake City when this article was published.

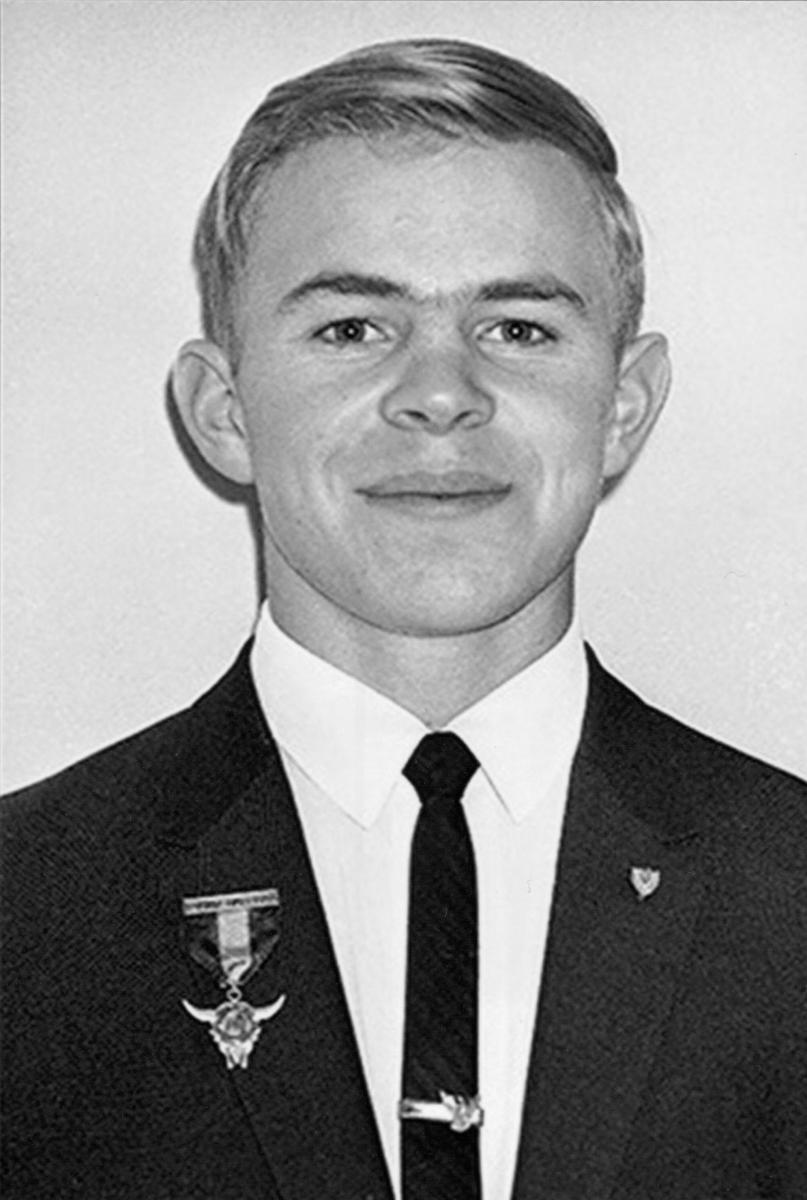

Darwin Johnson of Vernal (1967) wearing his Duty to God and seminary pin on his suit coat. This practice was common during the fifty-year history of seminary pins.

Darwin Johnson of Vernal (1967) wearing his Duty to God and seminary pin on his suit coat. This practice was common during the fifty-year history of seminary pins.

The history of the Church[1] is recorded not only in the words and events of the past but also in the artifacts left behind by previous generations. Artifacts serve as tangible reminders of our memories and add a sense of reality to our history.[2] The Church History Museum seeks to collect, preserve, and interpret the artifacts that illustrate the history of the Church. As windows to our past, artifacts enhance personal insight and understanding that in turn enlighten our appreciation of our history. The purpose of this discussion is to examine the historical context of recognition jewelry in the Church’s seminary and institute programs during a fifty-year period (1930–80). The history and context of this practice provides a useful perspective on the development of the Church’s seminary and institute programs.

The First Seminary Graduation Pins

For more than fifty years, students received a jeweled pin in recognition of their graduation from the Church’s seminary program. Parents and students alike valued these pins as evidence of individual achievement in an important Church program. The practice of distributing graduation pins began in 1928 and ended in 1981.

Fig. 1. William E. Tew Jr. Springville High School Yearbook, 1929.

Fig. 1. William E. Tew Jr. Springville High School Yearbook, 1929.

The history of seminary pins began in 1927, when William T. Tew Jr. served as the seminary principal for students attending Springville High School (Utah).[3] The seminary began in 1924 with the first meetings held in a local chapel during the construction of the new seminary building. In 1928, the seminary moved to the new building adjacent to the high school and honored forty-four graduates.[4] In some ways this graduating class was typical of those who came before, but there was one difference. For the first time, seminary graduates received from their seminary principal a pin in recognition of their efforts. This practice would continue in the Church for over fifty years, with thousands of seminary students receiving a graduation pin. Because this practice was never an official program of the Church’s seminaries and institutes,[5] it is worthwhile to understand the beginnings of this practice and the cultural context that enabled it to continue over the years without direct sponsorship from the Church.

The idea of a seminary graduation pin originated with discussions between two young seminary teachers, William T. Tew Jr. and Obert C. Tanner, who in 1927 taught in the Springville and Spanish Fork (Utah) seminaries, respectively. [6]

Fig. 2. O. C. Tanner, missionary photo, ca. 1924. Courtesy of O. C. Tanner Company.

Fig. 2. O. C. Tanner, missionary photo, ca. 1924. Courtesy of O. C. Tanner Company.

In the fall of 1927, knowing of Tanner’s work in Schubach Jewelry store in Salt Lake City before his mission, Tew asked Tanner if there was some type of recognition pin that might be used as a seminary reward. He felt that seminary should have a pin like the other high school groups and clubs. Tanner was sure that there would be something that would work.[7] He approached the Dennis Company in Salt Lake City to determine the feasibility and cost of manufacturing seminary pins. From the variety of possible designs they provided, Tanner selected one consisting of a “gold block letter” with an attached guard signifying the year.[8] As a trial, he ordered fifty pins and discussed with his friend Tew a plan to sell seminary recognition pins to the 1928 class of graduating students. Together they agreed to sell the pins to students at the Springville seminary, where Tew was principal. Tanner considered his first business attempt successful when he sold the pins for $2.25 each, resulting in a twenty-five cent profit from each sale. While Tanner continued to teach seminary for several more years, his first business venture proved to be a turning point in his life.

After this initial success, Tanner recognized the potential of his venture and decided to leave his seminary position and start what later became known as the O. C. Tanner Company. His first efforts would focus on selling school class rings and pins as well as the seminary graduation pins. He asked his friend Tew to join him as a business partner.[9] Although interested, Tew did not want to leave his position in the seminary. Tanner went on to form a national jewelry company, and Tew continued to serve as a successful seminary teacher and influential community leader.

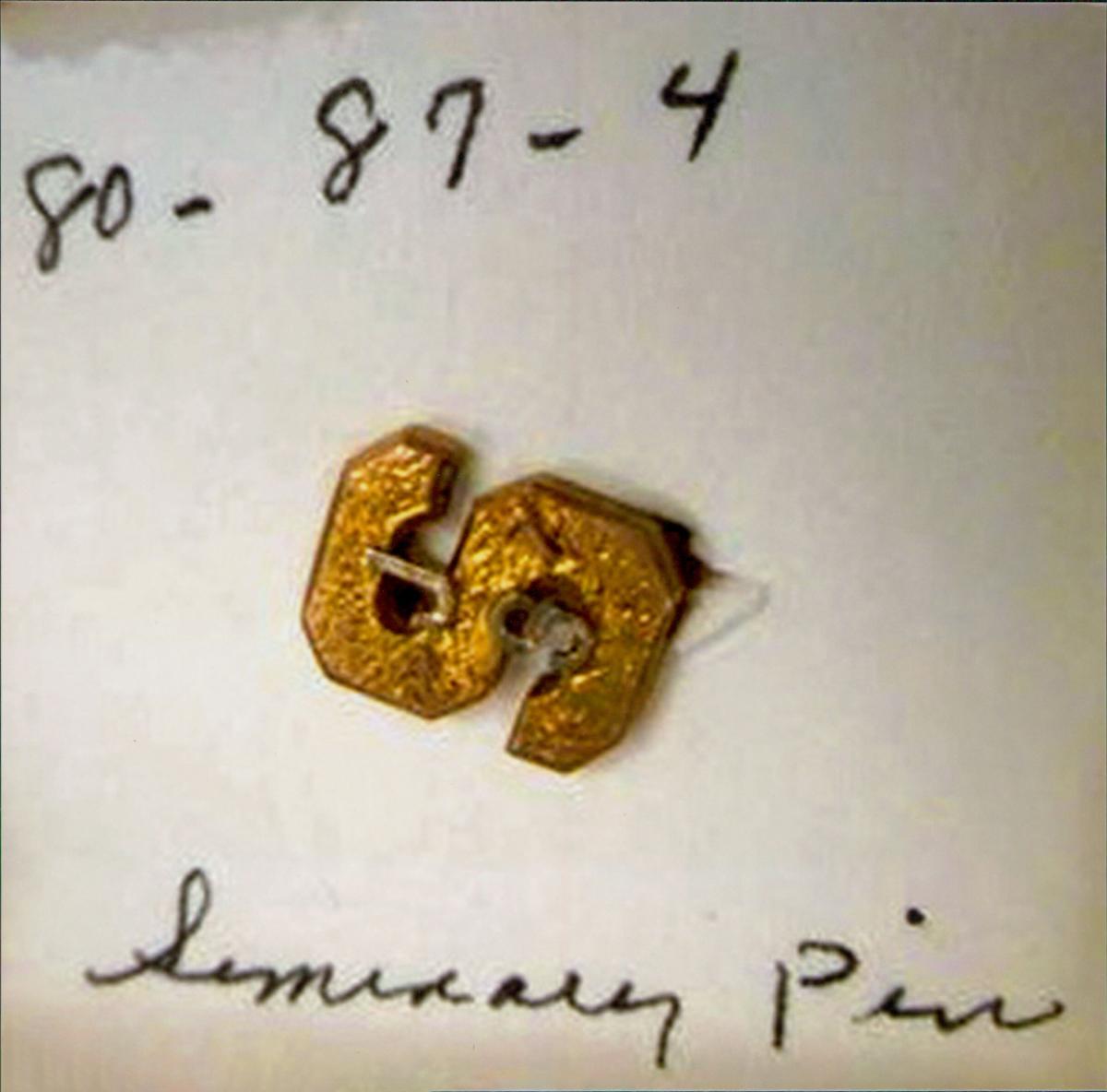

Fig. 3. Purported seminary pin, 1927. Courtesy of Church History Museum.

Fig. 3. Purported seminary pin, 1927. Courtesy of Church History Museum.

Is this the first seminary pin?

Because the donor designated this as a seminary pin and dated it 1927, it merited careful examination as a possible candidate for Tanner’s first seminary pin. He described his first pin as a block “S” with a chain guard attachment bearing the numbers 28, representing 1928, the date the first pin was sold to Springville seminary students. The pin in the museum bears the number 27 and does not have a chain guard. Other marks on the pin include the word “freshman” on the back and the letters “J” and “S” on the front. In addition, there is no evidence from microscopic examination that this pin ever had a guard chain attached. While the shape is a block “S”, it does not seem to fit the other descriptors provided by Tanner. The conclusion is that the date (27 rather than 28), the lack of a guard or related evidence, and the word freshman on the back suggest that this is not a seminary pin. More likely it was a high school class pin. Class pins were common at the time, and this particular pin was part of a donated collection that contained other school pins not related to seminary. While disappointing, this pin does not appear to be Tanner’s original pin, and the search continues to determine if the original pins still exist.

Historical Context

What in the culture of the community and the Church in the twentieth century encouraged the practice of recognizing seminary graduation with a jeweled pin? In the 1930s, the use of recognition jewelry was not unique to the seminary program. Early in the twentieth century, Church use of symbolic jewelry began with Relief Society membership pins. Other Church departments followed this lead and created their own pins, necklaces, sashes, and other award emblems. In keeping with practices at the time, seminary and institute students commonly wore items such as seminary graduation pins, returned-missionary fraternity pins, and other Church-related jewelry, including tiepins and necklaces. The Church department of Seminaries and Institutes ended this practice in the late twentieth century.[10] Understanding the cultural and historical context of the use of recognition jewelry will help explain why this practice endured for more than fifty years among the Church’s seminary students.

Humankind’s fascination with jewelry is evident throughout history.[11] “As our ancestors did, we see in [jewelry] magic, beauty, personal adornment, pleasure and wealth. . . . It is the most personal of objects.”[12] Jewelry satisfies a “superstitious need for reinforcing human powers by things that seem . . . more lasting and more mysterious than man.”[13] Jewelry thus provides a window on the past[14] and, as such, provides insight to the history of individuals or groups living at a particular time.

During the twentieth century, the use of recognition jewelry increased in popularity with a wide variety of business, social, and educational organizations. Reasons for wearing such jewelry included the desire to display visible symbols of social status or group association, the need for recognition of achievement, and the wish to identify sympathy with a particular cause or position.[15] The practice was not new as evidenced by its ancient origins in the symbolic jewelry of the Egyptians and other societies as early as 4000 BC. As skill in working with metal and precious stones developed, so did the market for various types of jewelry to satisfy social, religious, and political purposes.

Observers note that the wearing of recognition jewelry contributes to a sense of self-fulfillment through a symbolic display of one’s wealth, position, achievement, or association. Such displays enable individuals to achieve a level of fulfillment of the basic human need for esteem and recognition.[16] Because of these realities, it became common for people with shared principles and beliefs to wear symbolic jewelry that enabled others to recognize their unique position or achievement. The wearing of recognition jewelry secured symbolically for the wearer a level of status in the community or a personal sense of belonging to a group within the community. Jewelry used for these purposes was commonly found in academic, political, military, and social settings.

One early American use of jewelry for educational-recognition purposes began with the organization of the Flat Hat Club in 1750 at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. Members of this society wore a silver membership medal on their coats or jackets to identify their membership in this group. A few years later, students at this college organized the first fraternal organization in the United States: Phi Beta Kappa.[17] The members of this group wore a small emblem on their individual watch chains to identify their association.[18] The society later added badges and other jewelry that provided members with the additional recognition they desired. From this beginning, a national college fraternity system developed, each with its own style of recognition jewelry. The use of such jewelry soon became associated with academic societies throughout the country.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the use of recognition jewelry increased as high schools adopted popular college practices. High schools began using various forms of jewelry and other emblems to recognize membership in particular school classes, athletic teams, school organizations, and social groups. Early in the century, companies such as Jolsen’s and Balfour facilitated the use of recognition jewelry in the schools through a national marketing effort to public schools. Class rings, which had their beginning at West Point in 1835, became a growing trend, first for colleges and then high schools.[19] Soon national companies led the way in meeting market demands for recognition jewelry for schools and colleges. Because this practice addressed the basic human need for esteem and recognition, the demand for school pins increased to meet a growing number of purposes. LDS seminaries and institutes would also adopt this practice as a way to identify and recognize their students. As one seminary professional observed, “More than a culture of Seminary (or the Church) I believe it was more of a general culture. It was a significant practice in scouting, as well in schools, such as sports, drama, and other activities.”[20]

Early Distribution of Seminary Recognition Jewelry

In the 1930s, the O. C. Tanner Company was becoming a national leader in the manufacture and sale of recognition jewelry. Building on the existing tradition of marketing high school class rings and pins, Tanner also worked to increase the sale of seminary pins.[21] Finding it more profitable to control the production of seminary pins as well as the sales, the Tanner Company began manufacturing and selling its own seminary pin in 1932. The design and construction reflected those commonly used by schools, clubs, and social groups for recognition purposes.[22] The first pin manufactured by Tanner’s company featured a polished metal design with a blue enamel background. In the years that followed, Tanner’s pin designs became more sophisticated with the addition of semiprecious jewels placed in elaborate settings with religious symbols to increase the recognition factor of the pin.

Fig. 4. First seminary pin designed and manufactured by the O. C. Tanner Company, 1932. Courtesy of O. C. Tanner Company.

Fig. 4. First seminary pin designed and manufactured by the O. C. Tanner Company, 1932. Courtesy of O. C. Tanner Company.

The early process of making seminary pins employed a hand-stamping process using a sledgehammer and a forge press. The metal would be placed over the mold or “die,” and a sledgehammer was used to stamp the metal into the pin die. This “base” could then be decorated with symbols, stones, or enamel to finish the design.[23] While company and Church records are incomplete, it appears that during the decade that followed, the O. C. Tanner Company began producing a variety of seminary pins, which were advertised in high school yearbooks and through mailers to individual seminaries.[24] Seminary leaders could then select and order from the O. C. Tanner catalogue the pin they desired to award their students. Some questioned the marketing of the seminary pins: “Frankly, in my opinion, the promotion of recognition jewelry [in the Church] was done primarily by the companies basically seeking to increase their sales and income.”[25] Nevertheless, the use of pins became accepted among parents, students, and teachers, resulting in growing sales and distribution.

Fig. 5. Group of seminary graduation pins. Dates from the left: 1935, 1956, 1970. Courtesy of the Church History Museum.

Fig. 5. Group of seminary graduation pins. Dates from the left: 1935, 1956, 1970. Courtesy of the Church History Museum.

While the pins proved generally popular, individual student responses to receiving seminary pins varied. Seminary students outside the more concentrated areas of the Church typically did not receive pins.[26] However, in areas with established seminary programs, high school yearbooks show students wearing their seminary pin for their graduation photos.[27] Student comments at the time reflect interest in the seminary pins: “I proudly wore my seminary pin on my church suit for several years.” “I wore my seminary pin till 1970. Then I gave it to a girl for a promise.”[28]

This practice remained consistent until the 1970s, when yearbook photos no longer show students wearing seminary pins. Likely, this development was related to changing student attitudes. “I was pleased to receive my pin but did not want to wear it at church or school. That just was not the fashion. I put it in my keepsake box. It was a personal thing for me.”[29] While few corroborating records exist from this period for either the O. C. Tanner Company or Church Seminaries and Institutes, it is assumed that the pins declined in popularity during the decade of the 1970s because “the pin was just an accomplishment. Didn’t mean much to me.”[30] There is no mention in the minutes of the Church Board of Education regarding seminary pins until 1981, when the board approved discontinuing the practice of distributing seminary graduation pins.[31] “Pins did not continue after the 1980’s. I wonder if it was part of a big move to stop big seminary graduations and put them in the wards and stakes.”[32] This development did not seem to create a significant reaction among the students. “I don’t feel the loss of the seminary pin was a big deal. In my opinion it had no negative result for the program in any way.”[33] In the years that followed, seminaries used their leftover supply of graduation pins as rewards for a variety of seminary achievements other than graduation. In addition to this use of outdated pins, seminary leaders also awarded a Church-produced, simple, circular pin that became known by some as a “seminary letter.”[34] Students received these pins each year that they met specific seminary objectives. “I received my seminary letter for accomplishing goals defined by our seminary teacher. It was a big deal but we did not wear the pins.”[35] This practice continued until discontinued in the 1990s.[36]

Responses to Seminary Graduation Pins

In an effort to gather information relative to the responses of students, teachers, and administrators to the use of recognition jewelry, the Church department of Seminaries and Institutes conducted a formal survey of retired personnel.[37] The results of this survey reveal patterns within the group regarding how they responded to the practice. For the most part, students appreciated receiving a pin as part of the seminary graduation ceremony.[38] “I loved my seminary pin and wore it on my sweater to Church and other occasions. I thought it was beautiful.” [39] As part of the preparations for graduation, seminary leaders selected and ordered graduation pins, paid for either by stake or family funds. In selected situations, seminary principals used existing local seminary funds to purchase the pins. Students received their pin most frequently from a seminary leader at the same time they received their graduation certificate.[40] “I received my pin at graduation. One of the most valued jewelry items in my life. I remember that to receive my pin, I had to memorize a scripture. The scripture became important to me for the rest of my life. I still have my pin and still remember the scripture.”[41] Students frequently wore their pins on their church clothes along with other jewelry distributed by other Church youth programs. Those involved felt the pin symbolized accomplishment and paid tribute to the graduates. Most seminary personnel felt that the pin was an accepted tradition but unnecessary to the basic success of the program. “I never saw a real purpose for the pins. It was a tradition at this time in high school. Students wore a lot of pins for recognition. Seminary did not want to be left out.”[42] Teachers and administrators reported that the distribution of seminary graduation pins continued because it was part of the general practice of awarding high school pins; its long tradition was valued more by parents and students than by seminary personnel.[43]

Summary of the Use of Seminary Recognition Jewelry

For much of the twentieth century, local seminary leaders awarded recognition pins to seminary graduates. Throughout that period the O. C. Tanner Company served as the manufacturer and supplier of the pins. Students accepted the pins and wore them on Sundays and other special occasions. Parents and students appreciated the pin as tangible evidence of achievement and recognition. The practice remained imporant until the 1970s, when students began to lose interest. The general practice of awarding high school pins also declined in importance, and the Church Board of Education recommended that the practice be discontinued in 1981. Nevertheless, the seminary graduation pin remained the standard for recognizing seminary graduates for over fifty years.

Recognition Jewelry Distributed as Part of the Institute Program

The history of the use of recognition jewelry in the Church institute program for college students was different from that of the seminary pins. The institute jewelry helped promote, first, returned-missionary fraternities and, later, all such organizations that supported LDS college students. The purpose of such organizations was to encourage LDS student involvement in social and service groups related to the institute and other Church programs. Church leadership directed these organizations and provided full, authorized support from 1920 through the 1990s.

The use of Church-related recognition jewelry for college students began in 1920, when LDS college students first used pins as members of a college fraternity at the University of Utah known as the Friars’ Club.[44] The Friars’ Club was endorsed by university president John A. Widstoe, who felt that the fraternity would be a great support for returned missionaries attending the school.[45] The group members identified themselves with a triangular pin decorated with three rubies, each side of the triangle representing faith, loyalty, and love—the guiding principles of the organization. In the center of the pin was the image of a monk on a black enamel background.[46] The pin was to be worn over the heart to remind the members of their responsibilities as Friars. Produced by Salt Lake jeweler Parry and Parry, the pin cost eight dollars.[47] While the purpose of the fraternity was directly related to supporting Church standards and principles, the pin’s design and imagery followed existing college practices at the time.

Supported by a number of general Church leaders, the Friars’ Club lasted for a decade, disbanding in 1931, when Church leaders expanded efforts to assist returned missionaries.[48] They advised the Friars to merge with the newly reorganized Delta Phi fraternity, an organization created to focus more specifically on returned missionaries.[49] The members of the Friars’ Club voted that a merger be accepted and the club disbanded.[50] Following contemporary campus fraternity practices, Delta Phi adopted a symbolic crest and related recognition jewelry typical of the college fraternity styles at the time. The crest consisted of a shield with a jeweled star mounted on the shield. Other symbols on the shield included a lamp of learning, a scroll, and the Greek letters delta (Δ) and phi (Φ) at the bottom of the shield. [51] The membership pins used images from this crest in their design.

Fig. 7. Delta Phi membership pin (ca. 1950) and Delta Phi Kappa pledge pin (ca. 1960). Courtesy of the Church History Museum.

Fig. 7. Delta Phi membership pin (ca. 1950) and Delta Phi Kappa pledge pin (ca. 1960). Courtesy of the Church History Museum.

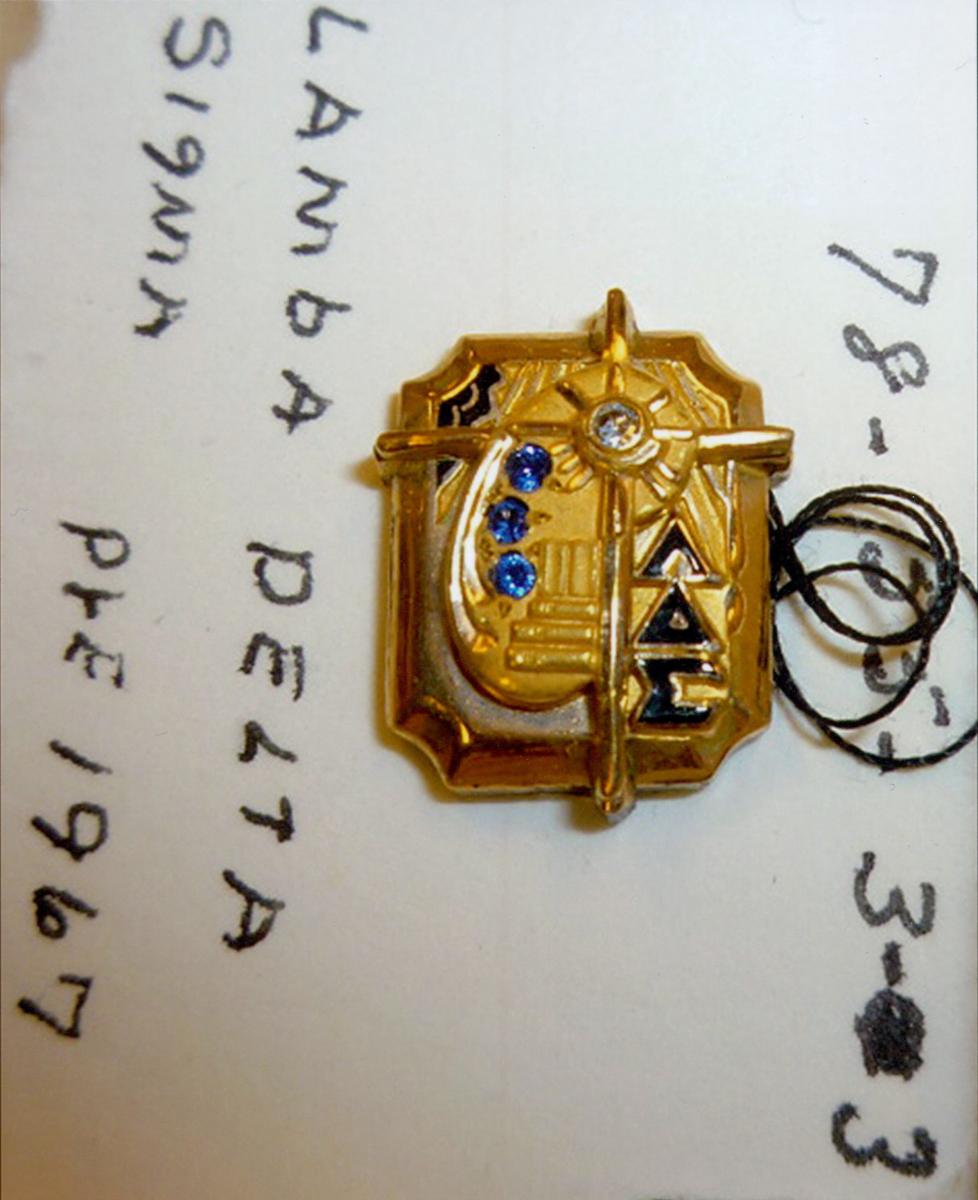

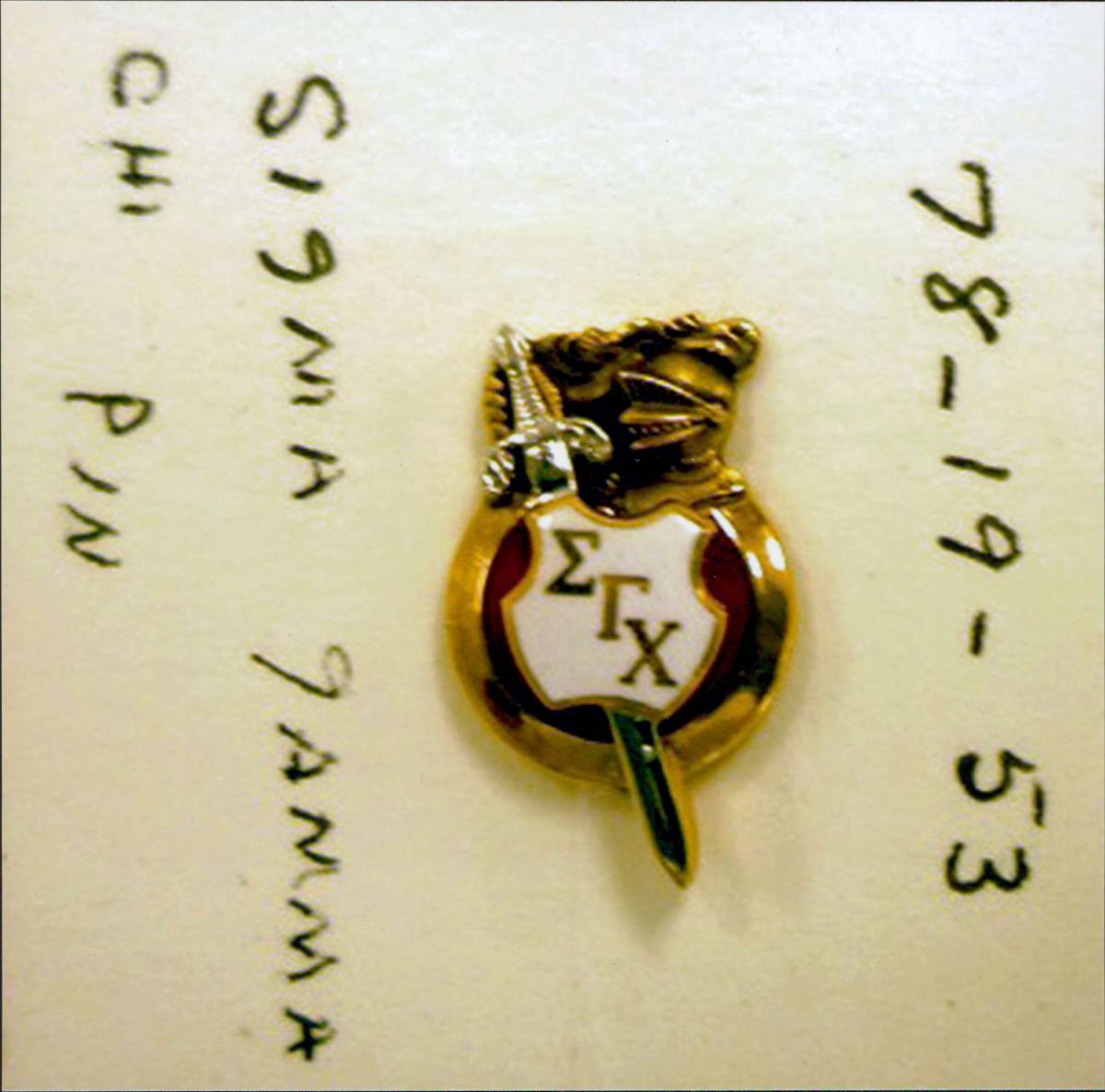

Fig. 8. Lambda Delta Sigma membership pin (ca. 1950) and Sigma Gamma Chi membership pin (ca. 1970). Courtesy of the Church History Museum.

Fig. 8. Lambda Delta Sigma membership pin (ca. 1950) and Sigma Gamma Chi membership pin (ca. 1970). Courtesy of the Church History Museum.

Delta Phi used three pins to identify members and potential members: the pledge pin, a Greek letter pin, and a membership pin. The pledge pin identified members who had yet to be initiated. The design of this pin originated with the four-pointed star on the membership crest. The membership pin, worn by initiated members, was made of 14-karat gold with a black shield similar to the crest. The Greek letters delta (Δ) and phi (Φ) figured prominently on the shield. Members could also wear a simple Greek letter pin displaying the letters delta (Δ) and phi (Φ). The fraternity encouraged every member to wear a pin.[52] The J. S. Jensen Company manufactured the first membership pins at a cost of fifteen dollars, but soon the O. C. Tanner Company became the jeweler of choice. [53]

Delta Phi continued as the leading fraternity for returned missionaries under the leadership of Church leaders such as John A. Widstoe, Matthew Cowley, Milton R. Hunter, and A. Theodore Tuttle.[54] However, as the number of Latter-day Saint students on campus increased, a need was felt for an additional Church-related fraternity. In response, Lowell L. Bennion assisted students at the University of Utah to organize a fraternity that Church leaders felt would be less like the Greek fraternities and more in keeping with the principles of camaraderie experienced in the mission field. As a result, students organized the first Lambda Delta Sigma chapters, one for male returned missionaries and one for female.[55] Lambda Delta Sigma’s open membership policy became more closely associated with the Church’s institute program, which was expanding at a rapid rate.

The relationship between Delta Phi and Lambda Delta Sigma proved interesting because the two fraternities often shared the same members. However, typically young men joined Lambda Delta Sigma before their missions and Delta Phi as returned missionaries. [56] Female returned missionaries and students did not join Delta Phi and eventually organized their own Lambda Delta Sigma group. To create their own identity, Lambda Delta Sigma offered its members several recognition pins.[57] The primary fraternity membership pin, designed by the artist Avard Fairbanks, displayed a rectangular base with a jeweled radial star, four books, and the Greek letters lambda (Λ), delta (Δ), and sigma (Σ). The fraternity offered several other pins to its members, including the pledge pin consisting of just the radial star and a simple Greek letter pin. The fraternity also contracted for the manufacture of a variety of other types of jewelry similar to those used by other campus fraternities, including tie tacks, necklaces, bracelets, money clips, and other items. Members obtained the fraternity’s recognition jewelry from the national fraternity council office through orders submitted by their individual chapters and paid for by individual members. The fraternity prescribed how the pin was to be worn and encouraged all members to wear it.

Changes came to both Delta Phi and Lambda Delta Sigma. In 1961, a national fraternity requested that Delta Phi change its name due to perceived confusion between the local returned-missionary fraternity and the larger non-LDS nationwide fraternity of the same name. As a result, Delta Phi became Delta Phi Kappa. The changes in the recognition jewelry proved minor with the addition of the Greek letter kappa (Κ). With that simple addition to its name, and hence to its jewelry, Delta Phi Kappa was able to continue. However, more sweeping changes were in store for Lambda Delta Sigma.

In the 1960s, the Church responded to increasing numbers of LDS college students with the organization of student stakes and the creation of the Latter-day Saint Student Association.[58] As these organizations became successful, some began to question the need for fraternities such as Delta Phi Kappa and Lambda Delta Sigma. After considerable discussion, Church leaders decided to organize a new male fraternity and reposition Lambda Delta Sigma as a female sorority. Delta Phi Kappa was not involved in these changes and moved away from direct Church oversight and administration for its few remaining years. Sigma Gamma Chi became the new Church-directed fraternity for male students, and Lambda Delta Sigma became the sorority for female students.

These organizations operated under full Church sponsorship as part of the institute program and the Latter-day Saint Student Association. These new groups promoted a variety of recognition jewelry for their respective members. Unlike previous practices, Church leaders approved the jewelry and provided for its manufacture and sale through existing Church distribution channels.

Lambda Delta Sigma retained the previous membership pin, with few modifications. Members also commonly wore the simple Greek letters ΛΔΣ as pins, necklaces, and other jewelry. Because of the preferences of the female membership, the design of Church sorority pins, necklaces, and other items became more stylish. Sigma Gamma Chi produced a new pin with a circular, red, enameled base with a sword and shield placed over the base. The Greek letters sigma (Σ), gamma (Γ), and chi (Χ) figured prominently on the white shield. Other recognition jewelry included rings, tiepins, and watches with the Greek letters, and a variety of items recognizing different types of achievements. Unlike prior Church-related fraternities, the wearing of jewelry became optional for both Sigma Gamma Chi and Lambda Delta Sigma. Members desiring to wear fraternity jewelry placed orders with existing chapter officers and individually paid the cost.

During the years that followed, college fraternal organizations experienced a general decline in membership. This was also true for the Church fraternity and sorority as well as for Delta Phi Kappa, which had merged with Sigma Gamma Chi in 1978.[59] In 2011, the Church Board of Education voted to discontinue the Church’s fraternity and sorority. Some chapters continued to exist for some time but eventually disbanded.[60]

Responses to Institute Fraternity and Sorority Jewelry

A survey conducted by Seminaries and Institutes in 2016[61] included responses to the use of seminary and institute recognition jewelry. Responses related to the institute program will be discussed here. Most participants in the institute portion of the survey observed that the use of recognition jewelry provided a sense of belonging to both Church programs as well as the general campus community. “It was important to me at the time I received it to show my identity. I enjoyed belonging to the fraternity and being involved. The pin gave it significance.”[62] Fraternity and sorority pins were “highly valued” by 38 percent of the respondents and “somewhat valued” by 63 percent.[63] One respondent fondly remembers, “I used my Delta Phi Kappa pin to ‘pin’ my future wife before we were engaged. . . . She still has the pin.”[64] It was not uncommon for males with pins to give them to their girlfriends as part of a general pre-engagement tradition, thus enhancing the meaning of the pin. While less than 40 percent of the institutes surveyed distributed the pins, those who did felt that they were part of the campus tradition at their university and provided a missionary opportunity. “[My pin was] a symbol of brotherhood, it identified my membership in the men’s organization at the institute.”[65] Unlike the seminary pins discussed above, the institute pins were associated with specific social groups that had a defined Church identity. “Lambda Delt was a huge part of growing our institute program. . . . Receiving the pins and wearing them was a powerful symbol of belonging.”[66] While most students seemed to value their pins, female members appeared more interested as evidenced by the variety of pins, necklaces, and other jewelry worn by the members. “The sisters were more prone to wear a necklace but the young men did not have the same fashion leaning.”[67]

Consistent with the general demise of college fraternities and sororities near the end of the twentieth century, LDS students also appeared to lose interest in Church fraternities and sororities. There were mixed emotions regarding the demise of these groups. Some felt that “it was a significant blow [to the Institute programs] when the LDS [fraternities] and the attendant jewelry was discontinued.” Others expressed a more commonly held opinion: “Jewelry was nice for those who wanted it, but was not very important to the overall purpose of the program.”[68] It appears that the end of these programs and their related jewelry came because “the practice of wearing such things was not in fashion.”[69]

Summary and Invitation

For over fifty years, the Church supported the distribution of recognition jewelry in both the seminary and institute programs. Thousands of former seminary and institute students have in their possession pins and other jewelry that marked their participation in these programs. For them, these items have become symbols of an important part of their personal history. The pins mark their graduation from seminary and participation in Church-related college organizations. They prompt memories of times past and the importance of Church programs in their youth. These items have also become part of the history of the Church in the twentieth century. They represent an important stage in the development of the youth and young adult programs of the Church, and the importance of participation in those efforts. While the use of recognition jewelry has disappeared from the programs of seminaries and institutes, history does record a time when such things greatly mattered to the youth of the Church and its leaders. In its mission to preserve such history, the Church History Museum maintains a collection of Church-program jewelry and supports research that aids in understanding this part of our history, placing such artifacts in their proper cultural and historical context.

Although the collection of seminary and institute jewelry is considerable, it is not complete. Therefore, an effort is currently underway to organize the collection to determine which years are represented so that missing pins can be acquired to complete the collection.[70] This is part of a larger effort that will eventually catalogue and describe the use of recognition jewelry in the Church during the twentieth century. Individuals desiring to participate in this project by sharing their experiences with seminary or institute jewelry or donating such artifacts to the Church History Museum should contact the Church History Museum, 45 North West Temple Street, Salt Lake City, Utah 84150; phone 801-240-3310; or email Churchmuseum@ldschurch.org.

Notes

[1] For the purposes of this discussion, the terms “Church” and “LDS” refer to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The terms “religious education,” “seminary,” and “institute” refer to the weekday religious education programs provided by the Church for the youth of the Church. For a full history of this educational effort, see By Study and Also by Faith: One Hundred Years of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2015).

[2] For a more complete discussion of the value of historical artifacts, see Daniel Miller, Material Culture and Mass Consumption (Oxford, UK: Oxford Press, 1987).

[3] Ralph K. Hammer and Wendell B. Johnson, History of Mapleton (Provo, UT: Utah Press, 1976), 173–74. William Thomas Tew Jr. (1885–1954) attended Brigham Young Academy and served a mission to New Zealand. Following his mission he completed his education. He taught school in Manti and Springville, Utah, before he became a farmer in Lost River, Idaho. He returned to teaching following a farm accident that made it impossible for him to continue farming. In 1921, a seminary opened in Fillmore and he became the first instructor. He taught there until 1925 when he became the seminary principal at Springville, Utah. He taught at this seminary until his retirement in 1953.

[4] Springville High School Yearbook (Springville, UT: Nebo School District, 1929), n.p.

[5] The Church Seminaries and Institutes department did not officially sponsor the practice of awarding seminary graduation pins. Local stakes and seminaries that desired to award pins ordered them from the manufacturer and assumed all associated costs. While general Church offices did not fund or directly support the distribution of pins, they did not discourage the practice. Robert Ewer (seminary and institute historian), interview by Dennis Wright, 22 February 2016, Church Office Building, Salt Lake City.

[6] Obert C. Tanner, One Man’s Journey: In Search of Freedom (Salt Lake City: The Humanities Center at the University of Utah, 1994). Following his LDS Church mission to Germany, Tanner taught seminary first in Spanish Fork and later at Granite, East, and South High Schools in Salt Lake City. During these years he worked on the side to start his jewelry company. After leaving his seminary position, he led a distinguished life as a nationally recognized businessman, community leader, and philanthropist. In addition to his leadership of the successful O. C. Tanner Company, he also served as professor of philosophy at the University of Utah. He received the National Medal for the Arts and a United Nations Peace medal; he also was an honorary member of the British Academy. Throughout his life he generously supported the arts and education.

[7] Sondra Latham (granddaughter of William Tew Jr. and employee of O. C. Tanner), interview by Dennis Wright, 27 June 2016. In a conversation with Latham in 1978, Tanner described how he and Latham’s grandfather had come up with the idea of a seminary graduation pin.

[8] Tanner, One Man’s Journey: In Search of Freedom, 158.

[9] Sharla Bohl (granddaughter of William Tew Jr.), interview by Dennis Wright, 29 March 2016. Tew family sources recite the account of Tanner and Tew considering a joint business venture with some humor and view it as their ancestor’s chance at fame and fortune, as told by Bohl of Springville, Utah.

[10] At this time, there was a general decline in the use of Church-related recognition jewelry. The most recent discontinued item of recognition jewelry was the Aaronic Priesthood Duty to God pin. Distribution of this item ended in 2010.

[11] Rose Leiman Goldemberg, All About Jewelry: The One Indispensable Guide for Jewelry Buyers, Wearers, Lovers and Investors (New York: Arbor House, 1983), 9.

[12] Goldemberg, All About Jewelry, 9.

[13] Joan Evans, A History of Jewellery 1100–1870 (Boston: Boston Book and Art, 1970), 39.

[14] Jack Ogden, The Intelligent Layman’s Book of Jewellery (London: The Intelligent Layman, Thornton House, 2006), iii.

[15] Marcus Baerwald and Tom Mahoney, The Story of Jewelry: A Popular Account of the Lure, Lore, Science, and Value of Gems and Noble Metals in the Modern World (New York: Abelard-Schuman, 1960), 13.

[16] Hugh Tait, ed., 7000 Years of Jewelry (London: Firefly Books, 2008), 11.

[17] Richard Nelson Current, Phi Beta Kappa in American Life: The First Two Hundred Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 4.

[18] Current, Phi Beta Kappa, 5.

[19] “History of Class Rings,” National Recognition Products, www.nrprings.com/

[20] Survey respondent, Initial Report Seminary and Institute Pins/

[21] Sarah MacConnell, “Class Pins for School and College. Giving Designs for Class, Society and Club Pins,” The Ladies Home Journal 17, no. 11 (October 1900): 17.

[22] It is interesting to note that the basic shape and design of Tanner’s first seminary pin reflects the fraternity pin Tanner wore while a student at the University of Utah. His fraternity, the Friars’ Club, was an LDS-associated social group that wore a triangle-shaped pin with the fraternity emblem in the center much like the design of the seminary pin.

[23] Cordell Clinger (O. C. Tanner Corporate Historian), interview by Dennis Wright, 12 April 2016.

[24] Clinger, interview. The corporate records of the O. C. Tanner Company do not contain historical files related to marketing methods or sales reports for seminary pins. Representative pin artifacts have been saved and remain on display along with the 2002 Olympic Gold Medals produced by the Tanner Company. While Tanner recognized the importance of the seminary market to the beginnings of his business, this part of his business quickly became only a small part of his national effort.

[25] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[26] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016. In the survey, 57 percent of personnel did not award graduation pins as part of seminary graduation. This group tends to represent those outside the Intermountain West.

[27] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016. Teachers surveyed who received seminary pins as youth reported valuing the pin as a symbol of their accomplishment in a worthy endeavor. Young men often wore their pins on their suits until their missions. The general reported appreciation of their own pins stands in contrast to the general indifference they felt towards the pins as seminary teachers and administrators. “I never saw a real purpose for the pins. It was a tradition. Most of the girls got one, but only a few of the boys. At this time high school students used a lot of pins, jacket, etc. for recognition. Seminary did not want to be left out.”

[28] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[29] Kay Morgan (1966 seminary graduate), interview by Dennis Wright, 15 October 2016.

[30] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[31] “Minutes of the Combined Concurrent Meeting of the Executive Committees of the Church Board of Education and the Boards of Trustees of Brigham Young University, Brigham Young University–Hawaii Campus, Ricks College, and LDS Business College, 23 June 1981” (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1981). Frank Day, assistant commissioner of education, discussed with the Board the declining interest of seminary students in seminary jewelry.

[32] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[33] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[34] The circular pins produced by the Church had limited distribution during the period following the era of awarding formal seminary graduation pins.

[35] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[36] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[37] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[38] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016. While young men frequently wore the jewelry on their Sunday jackets, girls tended to value the jewelry and wore it not only to church but also in other settings. Sometimes, young women had the pin made into a necklace.

[39] Carolyn Wood and Blaine Wood (1956 seminary graduates), interview by Dennis Wright, 10 September 2016.

[40] Initial Report 2016. Priesthood leaders awarded the pins 39 percent of the time and seminary leaders 44 percent of the time. Others mentioned in the survey included parents.

[41] Patricia Lake (1953 seminary graduate), interview by Dennis Wright, 20 September 2016.

[42] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016. Many seminary teachers reported that they did not really see a purpose for the pins other than tradition. While respondents reported that the pins were not essential to the program, they did admit that the students valued the pins as a symbol of their achievement.

[43] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016. In the study, 63 percent felt that the tradition continued because it became an expectation of parents and students.

[44] By Study and Also by Faith. 78–79.

[45] William G. Hartley, Delta Phi Kappa Fraternity, A History 1869–1978 (Salt Lake City: Delta Phi Kappa Holding Corporation, 1990), 19.

[46] Hartley, Delta Phi Kappa Fraternity, 27.

[47] Efforts to locate an original Friars’ pin have been unsuccessful. Research continues in this effort.

[48] Hartley, Delta Phi Kappa Fraternity, 35. David O. McKay and Adam S. Bennion favored suggestions that the Friars merge with the reorganized Delta Phi campus fraternity. This fraternity had existed as early as 1869 at the University of Utah, but it had disbanded.

[49] Hartley, Delta Phi Kappa Fraternity, 3, 15–17. Delta Phi was the first college fraternity in Utah organized in 1870 at the University of Utah. While it did not have a specific Church-related purpose, it did provide social support for students attending the university. It lasted until 1905 when it disbanded.

[50] Hartley, Delta Phi Kappa Fraternity, 36, 49. It is interesting to note that former Friar member O. C. Tanner was a member of the group that worked to reorganize Delta Phi and then served as a fraternity advisor and vice president of the alumni organization. Tanner’s company became the primary supplier for Delta Phi jewelry most of its history.

[51] Hartley, Delta Phi Kappa Fraternity, 80.

[52] Hartley, Delta Phi Kappa Fraternity, 66.

[53] Lambda Delta Sigma National Handbook, 8th ed. (Salt Lake City, UT: LDS Institute of Religion, 1965), 88. O. C. Tanner, the fraternity alumni vice president, later won the contract to manufacture the pins and did so for the remaining years of the fraternity’s existence.

[54] By Study and Also by Faith, 80.

[55] By Study and Also by Faith, 80–81. However, in practice many campuses had both male and female members in their Lambda Delta Sigma chapters.

[56] Hartley, Delta Phi Kappa Fraternity, 107–8.

[57] “Officers Jewelry and Accessories, Lambda Delta Sigma (LDS fraternity 1936–1966),” Church History Library, Salt Lake City, CR 1147.

[58] By Study and Also by Faith, 170–71.

[59] Hartley, Delta Phi Kappa Fraternity, 260.

[60] By Study and Also by Faith, 520.

[61] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[62] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[63] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[64] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[65] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[66] Craig Frogley (institute instructor), interview by Dennis Wright, 24 June 2016. A report from a retired University of Utah institute instructor described a decline in institute enrollment when the Church fraternity and sorority ended. He suggested that it was the identification with a Church social group that promoted institute involvement.

[67] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[68] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[69] Survey respondent, Initial Report 2016.

[70] The O. C. Tanner Company is directly involved in this area under the leadership of company historian Cordell Clinger. The company has committed to reproducing a historical set of seminary pins from existing original dies. This will be a valuable contribution to the museum’s research effort.