Review of By Study and Also by Faith: One Hundred Years of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion

Scott C. Esplin

Scott C. Esplin, "Review of By Study and Also by Faith: One Hundred Years of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion," Religious Educator 17 no. 3 (2016): 188–93.

Scott C. Esplin was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this article was published.

By Study and Also by Faith: One Hundred Years of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion. Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2015. Notes, black-and-white illustrations, 654 pp. with index. ISBN: 978-1-4651-1878-3, US $33.50.

By Study and Also by Faith: One Hundred Years of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion. Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2015. Notes, black-and-white illustrations, 654 pp. with index. ISBN: 978-1-4651-1878-3, US $33.50.

“In the history of the Church,” President Boyd K. Packer taught, “there is no better illustration of the prophetic preparation of this people than the beginnings of the seminary and institute program. These programs were started when they were nice but were not critically needed. They were granted a season to flourish and to grow into a bulwark for the Church. They now become a godsend for the salvation of modern Israel.”[1] Seeking to chronicle this history, the recent volume, By Study and Also by Faith: One Hundred Years of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion, captures the system’s rise from a humble beginning of seventy students in 1912 to become a worldwide organization that provides religious education to over 700,000 students a year.

In the volume’s foreword, Elder Paul V. Johnson, former Commissioner of the Church Educational System, outlines the book’s purpose: “We were in danger of losing a great deal of knowledge of our history. Some other organizations cut their connections to their roots and begin to drift. This organization could not afford this,” he warned. “Our history doesn’t limit us, but like a plant’s roots it anchors and nourishes us and is crucial for growth. Our history helps us grasp our identity and protects us” (viii).

The prologue adeptly overviews the foundation of education in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Drawing from the words of modern revelation and the practices of the early Saints, it outlines the groundwork laid for Seminaries and Institutes by educational endeavors in Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, and Utah. Importantly, the prologue connects the Church’s earlier academies and religion classes to the modern Church Educational System, helping the reader recognize that the seminary and institute programs were the continuation of larger efforts to nurture faith in the hearts of youth and young adults. While some readers might wish this and later parts of the book were strengthened by a discussion of religious instruction beyond Mormonism or a deeper examination of the alternatives to released-time religious education, the prologue nicely places the formation of the seminary and institute system within a larger Church context.[2]

Following the prologue, the book focuses its remaining nearly six hundred pages specifically on the history of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion. In chapters that are as long as one hundred pages each, the book details the operations of programs that grew beyond their Wasatch Front beginnings to their current reach around the world.

The authors, who, it appears from the acknowledgments, all have backgrounds in Church education, seem to grapple with a challenge faced by every teacher: too much material to cover and a reluctance to leave anything out. As one who has tried to talk more quickly in a class in order to teach more material, I resonate with the difficulty, or even the reluctance, they faced to “reduce and simplify.” However, the words of Elder Packer quoted earlier regarding the history of the program might apply to the volume specifically. From a reader’s perspective, some of the information the book contains is “nice but . . . not critically needed.” For example, a general readership likely does not need details of the Alpine summer school from 1927 and 1928 (48–50), a listing of extracurricular activities by teachers and students in the 1930s (62), the development of choirs at the Logan and Salt Lake City institutes in the 1940s and ’50s (111), a reference to William E. Berrett constructing a coffin for his deceased child (141), or the listing of computer reporting programs in the 1990s (418–19). The challenge of too much detail is especially evident in the latter half of the volume, where the authors write about events that they and some of their readers personally experienced. Of course, this difficulty is faced by anyone who attempts to write in an historical way about events of the recent past involving living subjects. The challenge increases when the writing is done by committee. Though the volume is well researched and seeks to be exhaustive, some of its information might better be placed in a footnote or in a separate collection altogether.

Admittedly, the book maintains its detailed focus on the seminary and institute systems. Therefore, beyond the prologue, which touches on other Church education endeavors that were foundational to the programs in question, the bulk of the book makes little mention of related religious education programs like those at BYU, BYU–Idaho, and BYU–Hawaii. To the authors’ credit, when the other Church universities are mentioned, it is always in the context of their connection to the history of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion. This is the case with the discussion of BYU President Ernest L. Wilkinson, as his role as chancellor of the Unified Church School System is emphasized, and with the overview of BYU–Idaho’s Pathways Program, as the book draws connections to the larger Institute of Religion system.

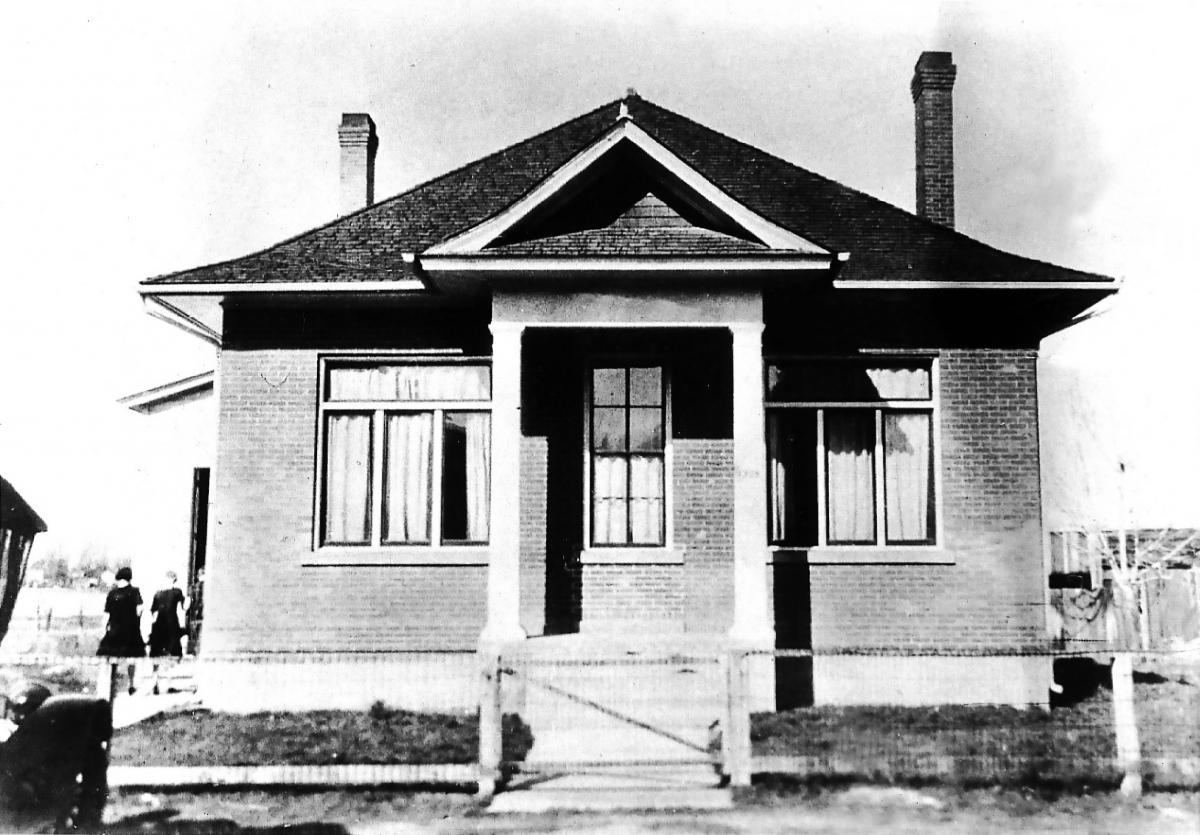

As an institutional history, the book is heavily organized around people. This may be appropriate because teaching is, first and foremost, a people-oriented profession. From the beginning of each chapter, which, with the exception of the prologue, starts with a full-page picture of a person central to the story (Thomas J. Yates, first seminary teacher; President Henry B. Eyring, two-time commissioner of the Church Educational System; Stanley A. Peterson, associate commissioner/

Granite High School Seminary Building, first LDS seminary building, ca. 1912.

Granite High School Seminary Building, first LDS seminary building, ca. 1912.

The focus on people comes at a cost, however—one that Elder Johnson acknowledges in his foreword. “Despite this volume’s relatively large size, it cannot be comprehensive. There are too many people, too many powerful accounts, and too many miracles and blessings to squeeze into one volume” (ix). Therefore, the emphasis on certain people, most often those with connections to central administration, exacerbates a challenge, especially for a program that is no longer limited to the Wasatch Front. The problem of selectivity is especially evident in the aforementioned appendix of administrator biographies, as the book does not clearly identify the criteria used for determining inclusion. With more than 3,000 current employees and over 44,000 volunteers worldwide, prominent people are going to be missed, even in a book of over six hundred pages. For example, Joseph M. Tanner is only mentioned in a passing sentence as a bridge between Karl G. Maeser and Horace H. Cummings, though Tanner served as superintendent of Church schools for five pivotal years (25). Additionally, a personal introduction in the text to nearly every central-office administrator, coupled with detailed biographies of these leaders in an appendix, subtly brands the book as an institutional production, though system-wide non-administrators and volunteers outnumber full-time administrators dramatically. Therefore, thousands of current and former full-time employees and volunteers who dedicated many years to the work of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion may feel their history was neglected. While the book will resonate with those who know and love the leadership of the Seminary and Institute systems, much remains to be written from the perspectives of women (443–47), students (453–56), and volunteers (456–59). In fact, institutionally, as many pages are dedicated to employment practices including compensation and contracts (541–44) as are specifically dedicated to the voices of women, students, and volunteers.[3] Furthermore, perspectives from non-English-speaking areas of the world are limited.

These observations are not intended to be criticisms of what is a remarkable product. In fact, President Packer’s observation that the program had become “a godsend for the salvation of modern Israel” is also evident in the history. The tone of the volume is admittedly and unapologetically positive, as a volume dealing with this topic and published by the Church should be. “The history of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion is one of faith, sacrifice, and devotion,” writes Chad H Webb, administrator of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion. “It is a history of commitment to and love for our Father in Heaven and His Son Jesus Christ. It is a history of love for the sacred word of God, of love for youth and young adults and of lives dedicated to teaching, lifting, preparing, and protecting them” (xi–xii).

While the book outlines challenges faced by Seminaries and Institutes of Religion over time, it openly asserts that God’s hand coupled with the sacrifice of loyal employees advanced the program. For example, describing the challenges faced in expanding beyond Mormonism’s traditional intermountain region, the book concludes, “As in Church education’s infant days, the right leaders and teachers came forward to overcome each obstacle” (93). This volume ascribes to the perspective voiced by President Joseph F. Smith: “The hand of the Lord may not be visible to all. There may be many who cannot discern the workings of God’s will in the progress and development of this great latter-day work, but there are those who see in every hour and in every moment of the existence of the Church, from its beginning until now, the overruling, almighty hand of Him who sent His Only Begotten Son.”[4] While not flawless, By Study and also By Faith succeeds in chronicling the divine hand in the history of Seminaries and Institutes.

Notes

[1] Boyd K. Packer, “Teach the Scriptures” (address to Church Educational System religious educators, 1977), 4.

[2] For example, additional detail could be added to clarify Elder David O. McKay’s initial opposition to the seminary program (41).

[3] These voices do emerge occasionally in other portions of the book, but not as separate sections.

[4] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, April 1904, 2.