Discussing Difficult Topics: Race and the Priesthood

W. Paul Reeve and Thomas A. Wayment

Paul W. Reeve and Thomas A. Wayment, "Discussing Difficult Topics: Race and the Priesthood," Religious Educator 17, no. 3 (2016): 126–43.

Paul W. Reeve (paul.reeve@utah.edu) was an associate professor of history at the University of Utah when this article was published.

Thomas A. Wayment (thomas_wayment@byu.edu) was publications director of the Religious Studies Center when this article was published.

There is no need to defend past statements on race because this generation of leaders condemns all racism, past and present. That includes racism within the Church.

There is no need to defend past statements on race because this generation of leaders condemns all racism, past and present. That includes racism within the Church.

Wayment: Paul, tell us a little bit about your background on race and Mormonism. What brings you to this discussion?

Reeve: I started research for the book Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015) in 2007. I was familiar with some of the existing historiography in the field of whiteness studies. The whiteness historiography has largely revolved around immigration and labor history. There have been studies of Irish immigrants who were racialized as not white or not white enough. The histories of Irish immigrants trace the ways in which the Irish attempted to claim whiteness for themselves and thereby become fully Americanized or assimilated. The same thing was true for Italian immigrants at the turn of the century and other immigrant groups coming into America. I was familiar with some preliminary evidence that suggested that the same thing was happening to Mormons. I wanted to do some research to see if that was true.

Wayment: And you noted two predominantly Catholic groups; is there anything there as far as religion and race?

Reeve: There is. One of the things that really interested me is that the existing historiography didn’t really pay attention to religion; it was mostly an immigrant and a labor historiography. The existing historiography does not pay significant attention to the Catholic religion of the Italian and Irish immigrants, a gap that I believed needed to be addressed. In my research, I had come across incidences where people from outside of Mormonism—Protestant Americans in particular—looked in at Mormons and suggested that they weren’t merely religiously different; they were sometimes physically different, even racially different. I started paying attention to that. I made a file, and started collecting sources, and decided that I could situate the Mormon experience within this bigger whiteness historiography and made the case that whiteness historians had largely ignored the religious component to this racialization that took place in the nineteenth century.

There are a couple of studies of Jewish immigrants which do pay attention to religion, and one of them, I think, is really quite nicely done—The Price of Whiteness is a Jewish whiteness study. For me, the interesting thing was that with the Mormons you have an inside religious group, a religion born in America, yet Mormons were being racialized as not American, not fully white, somehow a distinct “other,” not just religiously different but racially different.

So, I started the research. I had colleagues at the University of Utah who said I might get a nice journal article out of my research, but there certainly is not a book there. I started the research, and it just sort of snowballed. Friends and colleagues became aware of the project, and I would regularly get emails containing sources that fellow historians had come across. Once people became aware, they started paying attention to it. It seems to permeate interactions with Mormons in the nineteenth century.

I wrote a prospectus for a fellowship at the Huntington Library in California in 2007; they have a large collection of Protestant anti-Mormon tracts, and I thought, “If this is a theme, something that outsiders were projecting onto the Mormons, it’s going to show up in these Protestant tracts.” So I got this fellowship and spent the summer of 2007 at the Huntington reading these tracts. And the categories for the book started to emerge from the sources.

Wayment: You’ve also looked at whiteness in Mormon scripture, is that right?

Reeve: Yes, I mean the Book of Mormon obviously has passages that are charged with race and can certainly be read in very racist ways, and Mormons have read them in those kinds of ways. I think, perhaps, Mormons sometimes struggle to know exactly what is going on there. The narrative of the Book of Mormon especially revolves around a notion of the fallen Lamanites being redeemed into white and delightsome people, and obviously nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint leaders latched onto that and believed that their mission was to help redeem Native Americans, whom they understood as racially different from Euro-American Latter-day Saints. It was a mission for Latter-day Saints in the nineteenth century to redeem Native Americans from their fallen status and make them “white and delightsome.”

Wayment: So, an interesting thing you said—and I hadn’t planned to ask this—Mormons, at the time that they were developing this narrative of redeeming Native Americans, were also viewed as ethnically not white enough, or racially not white enough. Is that accurate?

Reeve: That is accurate. That’s really the point of the book: that Mormons were seen as not white enough; outsiders were never quite sure how to categorize Mormons. Nearly every marginalized group in nineteenth-century America was used as a comparison with the Mormons. There was a narrative of guilt by association: Mormons were missionaries amongst Native Americans, so outsiders concluded that Mormons were conspiring with Native Americans to wipe out true, white Americans.

Wayment: Like the events that took place in Missouri, or later in the Nauvoo period?

Reeve: Yes, both. Every time the Mormons were driven from their homes—so I’m talking about the expulsions from Jackson County and from Clay County, from the state of Missouri altogether, the state of Illinois altogether, or even the Utah war—there was a corresponding accusation of Mormon-Indian conspiracy. It happened every time. It was one of the rationalizations used to justify a Mormon expulsion. It was in the letters piling up on Governor Boggs’s desk before he issued the extermination order. The accusations took three key forms: Outsiders suggested that Mormons were conspiring with Indians to wipe out white Americans. They were intermarrying amongst them, and sometimes the argument was that the Mormons had become more savage than the “savages.” Outsiders also said things like, “White people really shouldn’t act this way”; “Mormons are not performing whiteness”; “they’re not true Anglo-Saxons”; “they’re more like Indians than they are like true, white Americans.”

Wayment: So, in a sense, there was this “othering” pressure, and Mormons now were other and Native Americans were other, so was it easy to say that they were both such different categories; they were conspiring against the United States. Is that an OK way to say it?

Reeve: Yes, I think that’s right. I think that this racialization process was the way in which outsiders justified discriminatory policies against the Mormons. How did you justify an extermination order against a group of people who looked like you? One way in which you did so was to suggest that in fact they weren’t like you, they were more like marginalized groups that nineteenth-century Americans felt perfectly justifiable in exterminating or expelling—Native Americans, African Americans, Asian Americans, immigrants. Mormons were conflated with all of those different groups and it is one way in which the nation justified discriminatory policies against them.

Wayment: So, isn’t it true that the Book of Mormon works in a different direction? It’s kind of recognizing an “other,” a different race, and trying to redeem that? Whereas the American experience, what you were saying, is trying to identify an “other” so that we can push it to the periphery, maybe exclude it. Is that correct?

Reeve: I think that is correct. Mormons in the nineteenth century read the Book of Mormon narrative and saw in themselves the need to become agents of redemption for Native Americans. From a twenty-first-century perspective, this was paternalistic and animated by colonialism, but nonetheless, the notion is that Mormons saw themselves as agents of uplift. They used racialized language in the way in which that uplift played out, but they saw their mission as helping to redeem the fallen decedents of ancient Israel. And Mormonism was born into a racial context in which President Andrew Jackson had signed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, the same year Mormonism was founded. Andrew Jackson had become convinced that Native Americans were not merely culturally different, but racially different, and in fact intermixing with white Americans had been a disaster. So the best thing to do was to remove them from their homes east of the Mississippi to an Indian country west of the Mississippi River. Mormons came along and suggested that they had a book that was reportedly a history of this group of people, and that Indians were in fact fallen descendants of ancient Israel and that they had a divine role in the ushering in of Christ’s return. The Mormon view of who Indians were shines in the face of the way in which Protestant, white America viewed Native Americans at the same time.

Wayment: So, it was almost countercultural, maybe even subversive to the American agenda at that time?

Reeve: Yes, that is one accusation absolutely leveled against Mormons. One of the themes that I trace is the way in which Protestant, white America made these arguments, these accusations against the Mormons. I also then look at the ways in which outsiders looked to the Native American context as a solution to the Mormon problem. So the Indian solution would be the solution to the Mormon problem; there was actually a reservation proposed for Mormons.

Wayment: I didn’t know that. Where was that located?

Reeve: After Joseph Smith’s murder in Illinois, there was a low-level official in Illinois who actually made a formal proposal that a Mormon reserve be created. He was explicit in saying that it was borrowed from this Native American, Indian reservation context. His proposal was to give the Mormons twenty-four square miles of land where only Mormons could settle, and there would be an agent appointed to preside. He borrowed from the reservation process in terms of the administrative structure. He proposed this to Mormons in Illinois, who responded by saying, “Well, it’s worth exploring,” because they really were looking for a new place to go by that point. Mormons were not necessarily opposed to the plan and even argued that twenty-four square miles was not enough land. The proposal did not receive much traction and died without coming to fruition.

Wayment: Let me shift gears a little bit. You’re familiar with the Gospel Topics essays, and the Church has now reflected on this period and made some statements regarding how we handled race, how we currently view race, and in a big picture I wonder if you would comment on what you feel the essay is saying, and maybe what it’s not saying. Help us read that from an historian’s perspective.

Reeve: Sure. Well, I think the “Race and the Priesthood” essay attempts to situate Mormonism’s priesthood and temple restrictions within a broader American racial context. Mormonism was born into a very charged racial atmosphere. We just talked about the racial atmosphere towards Native Americans; there was also a very charged atmosphere towards African Americans, and Mormonism was born into that context and can’t escape its consequences. So, what I see for the “Race and the Priesthood” essay is an effort to try to help Latter-day Saints understand that context. In the first couple of decades of Mormonism, there was an open racial attitude in terms of priesthood and temple admission. There were notions of universal salvation, a universal gospel message, and a universal male priesthood. Two well-documented black Latter-day Saints were ordained to the Melchizedek Priesthood in the first couple of decades of Mormonism. Then, what you see taking place across the course of the nineteenth century was a shrinking space for black Latter-day Saints within their chosen faith.

One of the most significant ways in which people claimed whiteness for themselves in the nineteenth century was in distance from blackness. Even Native American tribes passed laws against their tribal members marrying black people. The majority of states in the nation had laws against black–white racial mixing. I think that it is helpful to view race as a hierarchy, with Anglo-Saxons at the top and a variety of less desirable “races” beneath them. People were clamoring for a higher position on this racial ladder. Mormons were one of many groups that were racialized and pushed down that ladder at the same time they were trying to climb up and secure a more favorable rung for themselves.

Wayment: So do you see that happening as early as Brigham Young, prior to Brigham Young, or would you say mostly during the Utah period? Were they trying to grasp onto this American concept of whiteness?

Reeve: It happens even in the first couple of decades of Mormonism. So, the first documented black person to join the Church was in 1830 in Kirtland, the founding year of Mormonism. A man by the name of Black Pete joined Mormonism in Kirtland, part of a group that was converted by those early missionaries, and within a few months, I found a news report in Philadelphia and in New York stating that Mormons had a black man worshipping with them. This was not a celebration of Mormon diversity. Then, in Missouri, the accusation was that “Mormons are inviting free blacks to the state of Missouri to incite a slave rebellion and to steal our white wives and daughters.” Fear of race mixing was bound up in Mormonism, almost from the beginning, and that was a factor in the Mormon expulsion from Jackson County. So those accusations of a Mormon-Indian conspiracy are there, but also accusations that Mormons allowed and even promoted black-white race mixing. “Mormons accepted rogues, and vagabonds, and free blacks,” is one charge leveled against them in the state of Missouri. Mormons were accused of being too accepting of people that proper white American society knew should be excluded.

But in terms of the priesthood restriction, the first documented open articulation of a race-based priesthood restriction from a prophet was President Brigham Young in 1852 to the Utah territorial legislature. We know that a couple of black Latter-day Saints were ordained to the priesthood, and we know that Joseph Smith was aware of and sanctioned at least one of those ordinations, and his younger brother who was an Apostle at the time, William Smith, ordained the other well-documented black person to the priesthood.

Wayment: And the other being Elijah Abel?

Reeve: So Elijah Abel was one, and Q. Walker Lewis was the other. Joseph Smith signed Abel’s certificate in March of 1836. Abel was ordained on 3 March and Joseph Smith signed a ministerial certificate later that month, which certified that he was an ordained elder. It was a certificate that he was an ordained minister of the Mormon gospel, authorized to preach.

Wayment: Then he could be a missionary.

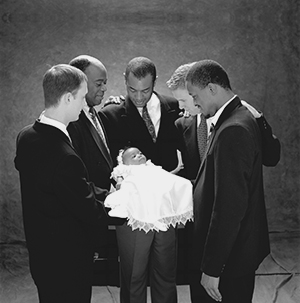

Reeve: Exactly. It indicates that he was ordained to the Mormon priesthood, an elder on 3 March 1836. Then on 20 December , that same year, he was ordained into the Third Quorum of the Seventy, which was a missionary quorum at the time, not functioning as an administrative unit like it does in the present day Church. Abel was ordained by Zebedee Coltrin on 20 December. All of those documents are at the LDS Church History Library. It is also important to note that LDS leaders were fully aware that Abel was a black man; Church documents call him a “colored” man. In US census records he was listed as a mulatto, which in a nineteenth-century racial and legal context equaled black.

Wayment: That was my question. There’s been some modern discussion on how black he was, if that’s an OK way to say it, and you’re saying that there is documentation that they interpret him as an African American.

Reeve: That’s right. Elijah Abel was in Cincinnati in the 1840s, and there was a Church conference that was held there. This was in 1843, so Joseph Smith was still alive. Joseph Smith was not at the conference but several Apostles were. The minutes of this conference survive in Church records, and Elijah Abel was present at this Church conference, and the Apostles said, (paraphrasing) “Well, we aren’t comfortable with a colored man preaching to white people, so he should relegate his preaching to the black population.” And Elijah Able responds by saying, “I don’t have a problem with that, I’m a member of the Seventy. It’s a missionary calling; I’ll preach to my own race.”

I’m citing that example to say that the documents support that LDS leaders fully understood him to be a black man; they called him a “colored” man. There are later remembrances that suggest that somehow Joseph Smith stripped him of his priesthood. There is just simply no evidence that this was the case. Abel was still a practicing Latter-day Saint in 1843, when Joseph Smith was still alive, and LDS Apostles were identifying him as a black man who had the priesthood and who was preaching the gospel.

Wayment: And actively in the Third Quorum of the Seventy.

Reeve: And the same holds true for Q. Walker Lewis as late as 1847. Brigham Young was on record as favorably aware of Q. Walker Lewis as a black man and a Melchizedek Priesthood holder. Minutes of a meeting in Winter Quarters substantiate this, where Brigham Young referred to Q. Walker Lewis as one of our best elders, an African in Lowell, Massachusetts, and a barber. So, Brigham Young himself is on record as late as 1847 as favorably aware of a black ordained priesthood holder.

Wayment: So that brings us to an interesting juncture. The essay, and I’m sure you’re aware of this, has been broadly interpreted as placing, if you will, blame—maybe that’s the wrong word to use—but kind of placing on Brigham’s shoulders the blame for instituting the priesthood and temple restrictions. So you’re saying that Brigham started out early accepting the ordination of a black man, and then in 1852 in the territorial legislature, he made some of those famous statements. Tell me, first of all, what historically is happening there? The recovery of whiteness or kind of trying to participate in American whiteness seems to be one factor, but what else could you add to that?

Reeve: Well, concerns of race mixing permeated American society. So there were laws dating back to the colonial period against white people marrying slaves, and not just slaves, but white people marrying black people. The majority of states in the nation had laws against interracial marriage between black and white. Like I mentioned earlier, even Native American tribes passed laws against their tribal members marrying black people. By December of 1847, Brigham Young became aware of Enoch Lewis’s marriage to Mary Webster in the Lowell, Massachusetts branch. Enoch was black and Mary was white. He also learned of the corrupt version of plural marriage that another black Mormon, William McCary, introduced at Winter Quarters. It involved interracial, sexualized, and unauthorized “sealings.” In response, Brigham Young spoke out strongly against race mixing; he even advocated capital punishment as the penalty.

Wayment: So that began to happen between 1847 to 1852?

Reeve: Yes. December of 1847 Brigham Young responded to news of both interracial circumstances. But the surviving minutes of the 1847 meeting at Winter Quarters do not mention a racial priesthood restriction. It was not until 1852 that Brigham Young openly articulated a priesthood restriction.

In terms of the “Race and the Priesthood” essay, and the perception that it places the blame, if that’s the right word, on Brigham Young, I think there are all kinds of important contextual elements coming into place here. I think that it’s a mistake to suggest that the priesthood ban was a result of Brigham Young’s inherent racism, or that he grew up as a racist. I do not believe that is what the essay implies. We have, like I mentioned, a very open racial attitude in March of 1847 from Brigham Young, and then you start to see a deterioration in Brigham Young’s own racial attitude between 1847 and 1852, and race mixing was a significant factor in that process. So I don’t see it as something inborn or inherent in Brigham Young.

Wayment: So one thing we could say, based on what you’re saying, is that the essay is not blaming someone per say, but maybe a larger cultural phenomenon?

Reeve: Well, yes, I think there are just so many moving parts. Certainly then, as far as historians have been able to determine, the priesthood restriction began with Brigham Young. There are no known statements from Joseph Smith making a race-based priesthood restriction or a temple restriction. In fact, the evidence seems to be really conclusive to the contrary, that Joseph Smith was aware of black people who were ordained to the priesthood, and that in the case of Elijah Abel, he sanctioned the ordination. No known statements from Joseph Smith of a race-based priesthood or temple restriction exist. Published in the Times and Season in Nauvoo is an open racial vision for admission to the Nauvoo temple. It announces that Nauvoo Saints will welcome all people, and specifically mentions people of all colors, into God’s holy house.

Elijah Abel was amongst the very first to do baptisms for the dead at Nauvoo, with no proscription at all against his participation. We know that he received his washing and anointing in the Kirtland Temple, which was as far as the temple ordinances were developed to that point. There is incontrovertible evidence that he was welcomed into that ritual. He wasn’t in Nauvoo when the endowment was introduced, so I don’t know what would have happened if he had been there. A belated remembrance records that Abel applied to Brigham Young for his endowment after he arrived in Utah, and Brigham Young told him no. In 1879, Abel did apply to John Taylor for his endowment and to be sealed to his wife, and that opened an investigation into Elijah Abel’s status as a black priesthood holder. If the priesthood restriction was unambiguously in place as late as 1879, then why the need for an investigation? As late as 1879, the leader of the church was unsure of how to proceed regarding race, the priesthood, and temple admission. After conducting an investigation in which Abel produced his priesthood certificates, Taylor allowed Abel’s priesthood to stand, but denied him temple admission.

So, once again, there is all kinds of evidence that LDS leaders knew Abel as a black person and as a priesthood holder. So, in terms of laying it all on Brigham Young, I guess that is kind of what we’re grappling with. The “Race and the Priesthood” essay is such a truncated exploration of this. It is difficult to capture the complexity of the priesthood and temple restrictions’ evolving history in such a short essay. If people are concerned that it’s all being laid at Brigham Young’s feet, ultimately I think it’s much more complicated than that. Yes, the restrictions began under Brigham Young and then take on a life of their own. They developed in fits and starts across the course of the nineteenth century. A lot more people were involved in that process, especially as the restrictions accumulated a growing precedent. I don’t see the restrictions as firmly in place until 1908. The last brick in the wall of exclusion, I think, was Joseph F. Smith in a meeting that took place in 1908. Joseph F. Smith in this meeting falsely remembered that Elijah Abel’s priesthood had been declared null and void by Joseph Smith himself. I think that was the last brick in the priesthood and temple restrictions becoming entrenched and firmly in place.

In my estimation, you have to erase from collective Mormon memory the black priesthood holders that complicate the story. Joseph F. Smith, in that 1908 meeting, basically said that the priesthood restriction had been in place from the beginning, God put it in place and man cannot do anything about it; it would take a revelation to get rid of it. In fact, that is what happened seventy years later; it did take a revelation to get rid of it. But that new memory that it had always been a white priesthood and that temple admission had always been white is fully solidified in 1908, when he erased from collective Mormon memory the black priesthood holders that complicated that narrative.

Wayment: And later, others developed the idea into a fully formed wall to protect this idea.

Reeve: That’s right.

Wayment: I want to put you in a difficult situation for a minute. So you’re a teacher, a Latter-day Saint teacher, of college-aged and high school-aged students, and you have a student who has a very simplistic narrative, that the Church is racist and our past is racist, and yet you’ve painted a wonderfully complex picture and very granular. How do you help speak to that? And I know that kind of puts you out of your academic mindset, but what could you do to help, or help a teacher, find a way to talk about this without placing blame on a single entity? That’s a large question, I apologize for it.

Reeve: Yeah, well you know, what I see, and what’s really striking to me in exploring this, is that Latter-day Saints were converting to Mormonism from a variety of backgrounds and understandings about the political issues of their day, and a major political issue in the nineteenth century was race, slavery, the status of African Americans, and abolitionism. And Mormonism was casting a wide net in the nineteenth century and drawing all of these people in, and they came into Mormonism with their political positions intact. So, Mormonism brought into the fold abolitionists and anti-abolitionists, white slave masters, black slaves, and free blacks; all of them were welcomed into the Mormon gospel fold.

Other religious traditions in the nineteenth century ended up splitting or going through schisms as a result of those same hot political issues. Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians either split or experienced a schism. Mormonism escaped those fates because they accepted people from all of those categories into the gospel fold. It came to a head in 1852, when Brigham Young tried to figure out how to make order out of the diverse group of people who had gathered to the Great Basin. What should Utah Territory do with the black slaves who had been brought to the territory by their white slave masters who had converted to Mormonism in the South? Some of the black slaves were also Mormon converts themselves. Brigham Young and the territorial legislature determined that white people would preside over black, and free would preside over bound. That is the order that Brigham Young and the legislature created out of the diverse population that had gathered to the Great Basin. So a variety of outside political positions became inside theological positions as this played out across the course of the nineteenth century. Those who converted to Mormonism brought their political and racial attitudes with them. Unfortunately, this had an impact on how the Mormon racial story played out theologically.

Wayment: That’s fascinating. That’s a really great point to make, and I think you’ve helped me see something there. Can I push you a little bit harder on that? Tell me about 1978. So, it was a long time later and the racial issue was pretty hot in ’78, but it seems in America it had reached its pinnacle a generation earlier. Do we wait till ’78 in part because of what you described? Mormons exist on this broad spectrum of backgrounds and beliefs and it takes that long to bring us together as a people. Is that one of the reasons for the delay?

Reeve: Yes, I think that the notion that priesthood and temples were white from the beginning really became entrenched in the twentieth century. No one remembered Elijah Abel and Q. Walker Lewis. They had been forgotten—erased from collective Mormon memory. The fact that there were black priesthood holders to complicate the Mormon racial understanding was gone. Mormons had arrived by the 1950s in terms of their acceptance as Americans. The Mormon notion of what it meant to be an ideal American finally dovetailed quite nicely with what mainstream society thought it meant to be an ideal American in the 1950s. Mormons had really made themselves over into these apple-pie-eating, baseball-playing, flag-waving, uber-Americans. They were monogamous and white and very traditional, and it fit with the post-World War II vision of what it meant to be an American—the Leave It to Beaver vision. But, right at the moment when Mormons arrived and are viewed as acceptable, the nation started to move in a different direction. The civil rights movement began, and rather than moving with the nation, Mormons entrenched behind segregated priesthood and temples.

David O. McKay would, however, begin the slow process of change. He went to South Africa in 1954, the same year as Brown v. Board of Education, and in South Africa you have people who looked white who were being denied ordination into the priesthood because they couldn’t trace their ancestry out of Africa. So the policy as it was being implemented in South Africa, because of the mixture of the races there, was basically guilty until proven innocent. You had to be able to trace your ancestry out of Africa in order to be eligible for ordination to the priesthood. David O. McKay unilaterally reversed this policy to a policy of innocent until proven guilty. He said it’s better to err on the side of mercy. “Why are we preventing these people from being ordained to the priesthood,” he questioned. “Let’s give them the benefit of the doubt—let’s ordain them to the priesthood. Then, if we find out later that there happens to be some African ancestry, we can deal with that, but why prevent a whole group of people, who at least on the surface look white, from being ordained to the priesthood?”

He also interpreted the priesthood restriction to apply only to those of African descent, so black Fijians, Filipino Negritos, Australian Aborigines, and Egyptians were all ordained to the priesthood before 1978. Then, you have a variety of other factors that came into play: Mormonism moved into international locations where mixed races were the de facto racial heritage of the bulk of the population. Brazil, for example, South Africa, and other Central and South American countries all had a mixture of these populations as a result of the slave trade. Good luck trying to figure out if a person had “one drop” of African ancestry in that context. Mormonism had adopted a one drop policy in 1907, that is that one drop of African ancestry would exclude a person from being admitted to the temple or to the priesthood. In the United States, let alone in countries with large percentages of mixed-race ancestry, it was almost impossible to ferret out one drop. We know now from DNA evidence that we are really intermixed—one big family across the globe.

The São Paulo Brazil Temple was announced, and you had faithful, black Latter-day Saints who were contributing their hard earned money to a building they knew they wouldn’t be able to enter. LDS leaders from Salt Lake flew to Brazil and met those Saints, and it touched them. They became more concerned about how they might let them into the temple instead of how they were going to keep them out.

I think also that the Spirit led out in front of LDS policy that dragged behind. On the continent of Africa itself, for example, entire congregations considered themselves to be Latter-day Saints based upon LDS literature they had encountered. They wrote to Church headquarters asking for missionaries, asking for more literature, asking for representatives to baptize them. They formed their own congregations. That was another pressure that brought the question to the forefront. Then you also have to take into account the various personalities amongst the leadership. Spencer W. Kimball, as an Apostle, was on record as early as 1963 calling the priesthood restriction a “possible error,” which he said the Lord could forgive. So, he is on record as early as 1963 with a very open attitude. You have Hugh B. Brown, who in 1969 attempted to remove the priesthood restriction simply by policy vote. He argued that “there was not a revelation that put it in place, so let’s remove it by vote; it’s a policy, so let’s get rid of it.” McKay himself had interpreted the restrictions as policy, not doctrine. Hugh B. Brown, however, was unable to achieve consensus. Harold B. Lee believed that it would take a revelation, and so that delayed things. Harold B. Lee became the next President. He had a short tenure, and then Spencer W. Kimball became President, and like I said, was on record with a more open attitude and seemed willing to take his case to the Lord and reported a revelation in June of 1978.

Wayment: That’s fascinating. That’s some great detail there. What do you feel needs to be part of this discussion to make it work for the average reader?

Reeve: So I think the question about Brigham Young—I don’t know if maybe I didn’t explore all the possible avenues there. I guess for some people, or for a lot of people, it comes down to this question to prophetic fallibility and what we should do with that as Latter-day Saints. For me, I don’t have a vision of a micromanager God who directs every finger lift. In fact, I don’t see God revoking a prophet’s agency when he makes him a prophet. If a prophet has agency, then a prophet can make a mistake. For me, the framework that works to help me not just with this but with a variety of issues that come up in navigating sometimes challenging waters is a principle articulated by Ezra Taft Benson when he was an Apostle. He articulated what’s called the “Samuel principle.” He referred to the Old Testament when the children of Israel asked for a king and Samuel told them no. They wanted to be like other kingdoms around them, and finally God said to Samuel, “Samuel they haven’t rejected you. They’ve rejected me. Give them what they want.” President Benson said that sometimes, within certain parameters, God gives us what we want and lets us suffer the consequences. It was a decision with long-term ramifications that lasted for several generations to switch to a monarchy. God allowed the children of Israel to live with the consequences of a monarchy.

I see that principle as something that is at play, for example, with Joseph Smith and the 116 lost manuscript pages. God gave Joseph Smith what he wanted and let him suffer the consequences. God called his prophet to repentance and in the revelation he gave to Joseph Smith he told him that he lost the ability to translate and that he had trusted more in the arm of flesh than he trusted in God. God let Joseph Smith suffer the consequences. The other example I think about is in Kirtland, Ohio, when the Saints wanted to open a bank. They applied for a bank charter, but the state of Ohio rejected the application. Joseph Smith decided to move ahead anyway. He opened a bank without a charter and called it an anti-banking institution. And a lot of Latter-day Saints in Kirtland believed that Joseph Smith had given them assurances that their money was safe. When the bank failed, they lost their money and their faith. It led to what’s called the Kirtland apostasy. Some of Joseph Smith’s closest associates dissented in that period. I look at that experience and say, “Well, God obviously knew the bank would fail, why not tell Joseph Smith simply, ‘Hey bad idea, you’re not a banker. Don’t go there—it’s going to cause all kinds of problems and people are going to lose their faith over this.’” God didn’t intervene: he let Joseph Smith open the bank and suffer the consequences.

When Brigham Young announced a priesthood restriction to the territorial legislature, God didn’t come down and stop him from doing so—he didn’t intervene. He didn’t say that in implementing a racial priesthood and temple restriction that it would lead to an entrenched policy that would be problematic to remove later and would bring a significant weight upon the Church. He let Brigham Young articulate a policy, a rationale for a priesthood restriction that I think took on a life of its own and let us as a body of Saints suffer the consequences. Some white Latter-day Saints grew increasingly secure in feelings of racial superiority, beliefs in divine curses centered on skin color, and the development of a theology that suggested that our brothers and sisters are somehow inferior to us.

The other thing I think is important for people to realize is that Brigham Young used one rationale—and one rationale only—for the priesthood restriction. He never deviated from it. I hear so much confusion about the notion that we had a racial priesthood restriction because of the Book of Mormon. Brigham Young never drew upon the Book of Mormon, never drew upon the Book of Abraham, never drew upon the Book of Moses. He used one rationale and one rationale only. He said that Cain killed Abel, and because Cain killed Abel, all of Abel’s decedents would need to receive the priesthood before Cain’s supposed decedents could receive the priesthood. And he believed Cain’s decedents were black people—that the mark that God put upon Cain was a black skin. That idea predates Mormonism by a thousand years; it is a part of the broader Judeo-Christian tradition, and Mormonism inherited it and used it to its own ends.

Wayment: A curse-of-Ham kind of thing?

Reeve: A curse of Cain, and then there was a corresponding curse of Ham, two different kinds of curses that played out. Brigham Young brought that curse of Cain into Mormonism and gave it theological weight. He never deviated from that; he never used “fence-sitter” or “less valiant in the war in heaven.” That was an explanation that grew up outside of official channels, because Brigham Young set up a theological problem in the curse of Cain explanation. Joseph Smith said we will be punished for our own sins and not for Adam’s transgression, and yet Brigham Young’s curse of Cain held the supposed descendants of Cain responsible for a murder they took no part in. Why aren’t white people responsible for David’s murder of Uriah? Why isn’t there a multigenerational curse around that?

Wayment: So they have to seek an explanation, scripturally.

Reeve: So other Church leaders had this alternate explanation. They thought there must be some sort of agency at play here, because Brigham Young’s accusation removed agency from the equation. Black people must have made some decision in the premortal existence that led to them being born into black skin and this cursed lineage. So, sometimes the invented explanation was that they were neutral in the War in Heaven. Brigham Young rejected that outright in 1869. To the School of Prophets, he said there were no neutral spirits in the War in Heaven; everyone chose sides. Then Brigham Young returned immediately to the curse of Cain explanation for black skin and the priesthood restriction. But that didn’t get rid of the idea of neutrality or black people being “less valiant”; other leaders would return to it. It would shift from neutral to less valiant.

I think that it’s an important point for people to be aware of, that there’s only one explanation that Brigham Young gave. He never deviated from it throughout his entire life. He resorted only to the Bible, the book of Genesis, and Cain’s murder of Abel. People in the 1880s started to refer to the Book of Abraham, like George Q. Cannon, and then that would take on a life of its own. The Book of Abraham wasn’t canonized until 1880, and Brigham Young never resorted to it. Joseph Smith gave us the Book of Abraham, and there’s no record of him using it as justification for a race-based priesthood restriction. So it’s important to have all that in our understanding of what the only rationale was for a prophet/

The other important idea to keep in mind is that all of the previous explanations have now been disavowed by this generation of leaders. The First Presidency and the Quorum of Twelve approved the “Race and the Priesthood” essay. It disavows all of the previous justifications. There is no need to defend past statements on race when this generation of leaders has disavowed them. And this generation of leaders condemns all racism, past and present. That includes racism within the Church. It has now been condemned.