Perspectives from the Global Expansion of Latter-day Saint Religious Education

Casey Paul Griffiths and E. Dale LeBaron

Casey Paul Griffiths and E. Dale LeBaron, "Perspectives from the Global Expansion of Latter-day Saint Religious Education," Religious Educator 17, no. 2 (2016): 118–37.

Casey Paul Griffiths (casey_griffiths@byu.edu) was a visiting professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this article was published.

E. Dale LeBaron (1934–2009) was a professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this article was published.

The seminary program was established in 1912 at Granite High School in Salt Lake City. Over time it grew and spread.

The seminary program was established in 1912 at Granite High School in Salt Lake City. Over time it grew and spread.

While fresh-faced missionaries are often seen as the symbol of Mormonism throughout the world, the network formed by professional educators in Seminaries and Institutes also provides an important support in the global structure of Mormonism.[1] During the 1960s, the international expansion of Latter-day Saint religious education provided a number of daunting challenges. The first wave of international Church education began in the 1950s under the direction of President David O. McKay, who led Church leaders in establishing school systems in the islands of the Pacific, Mexico, and parts of South America. However, as the Church continued to make progress in a number of different cultures, it soon became clear that the establishment of a Latter-day Saint school system in every country where members of the Church lived was infeasible. Recognizing the Lord’s commandment to “teach one another the doctrine of the kingdom” (D&C 88:77), Church leaders instead chose to direct their efforts toward establishing a system of weekday religious education, flexible enough to reach every member, regardless of where they lived. These educational programs, established in a remarkably brief period of time, came into being through the efforts of a group of American teachers sent throughout the world to establish the programs. The programs then grew to full maturity through the lifelong efforts of indigenous members of the Church all around the world.[2]

Calls for Help

The seminary program was established in 1912 at Granite High School in Salt Lake City. Over time it grew and spread, eventually replacing the system of Church-sponsored schools, called academies, throughout the Intermountain West of the United States. One of the appeals of the seminary program was its relative flexibility and inexpensive nature.[3] The seminary program took advantage of local public educational systems to reach out to Church youth, allowing the Church to do what it did best: provide spiritual education on a weekday basis. These programs began with students being released during the school day to attend class at a nearby Church-owned facility, thereby avoiding the nettlesome concerns of mingling church and state. Later, as the Church spread outward from the Mormon-culture regions of the United States, Canada, and Mexico, early-morning seminary programs, taught by nonprofessional teachers, allowed young Latter-day Saints to study the scriptures on a daily basis throughout North America.

By the 1960s, the question of how to bring Church education to the growing number of Church members around the world became paramount. The earliest documented request for seminary and institute programs came in 1961, when a letter arrived at Church headquarters from the president of the Brisbane Australia Stake requesting permission to start a seminary program. President McKay and Ernest Wilkinson, the chancellor of the Church School System, both considered the letter but felt the time was not yet right for the seminary program to expand outside of North America.[4] President McKay’s available papers provide no reasons, but a letter written near this time from Elder Delbert L. Stapley to Elder Gordon B. Hinckley, who were both members of the Quorum of the Twelve, provides some clues into the challenges deterring Church leaders from launching the programs. Stapley wrote, “None of the stakes or missions in Australia are able to carry forward the Church Seminary program. . . . It seems in connection with seminary that we do not have a concentrated group of students in any given area nor do we have qualified instructors to successfully carry forward the seminary program.”[5]

William E. Berrett, who served under Wilkinson as the head of religious education during this time, also began to receive requests from members around the world for religious education programs. Some letters came from American servicemen stationed abroad. One serviceman’s letter to Berrett began simply, “Dear Brother Berrett: HELP! . . . My immediate charge is to get religious education off the ground here in the Frankfurt [Germany] area this fall with direction to become more fully organized as soon as possible . . . So— — —HELP!”[6] Urged on by such requests, Berrett worked to establish seminary classes on American military bases in Germany and Japan, all the while recognizing the more pressing need to bring religious education to the local membership of the Church.[7]

At the request of Ernest Wilkinson, Berrett personally traveled to England in the summer of 1963 to investigate the possibilities of establishing seminary programs. Upon his return, he gave a stark report to the Church Board of Education on the possibility of establishing classes in Europe: “Members of the Church are of necessity placed in important Church positions without adequate understanding of the Gospel or Church leadership,” Berrett reported to the Church Board of Education, indicating the pressing need for more religious education. However, Berrett also indicated that the circumstances were ill suited for any programs like the ones currently in operation. “Only a few wards and large branches have enough members of high school age to constitute a seminary class of even 15 members, and these are highly scattered geographically,” Berrett noted.[8]

It was clear that the traditional methods of seminary would not meet the needs of the international membership. Berrett subsequently directed the curriculum team to develop a new method of teaching seminary. Ernest Eberhard, the head of curriculum for Seminaries and Institutes (S&I), assembled a team to examine the problem and developed a new program of home-study seminary. Berrett’s staff developed a series of outlines that students could complete at home under parental supervision. The students would then meet once a week in a classroom setting, decreasing the need for travel, and once a month in a larger setting with all the LDS youth in their areas. These monthly gatherings, focused as much on training the local teachers as on providing the students with social interaction, came to be informally dubbed as “Super Saturdays.” The program began among the scattered Church membership in the Midwestern United States and was declared a success. By 1968, the program was ready for its first test abroad.[9]

Launching the Movement: John M. Madsen and the United Kingdom

After securing permission from the Church Board of Education, Berrett’s staff began searching for teachers to leave the United States and set up the international programs. John Madsen, a twenty-nine-year-old seminary teacher in Salt Lake City, was the first teacher selected to go to England. The Madsens were fairly new to the S&I program. They were newlyweds and had one child. When they left to travel to England, Diane Madsen was pregnant with their second daughter. John Madsen was a former missionary from the British Isles whose lifelong dream was to teach in the seminary program.[10] In August of 1968, the Madsens embarked for England.[11] John Madsen recalled the electric atmosphere of the time: “There was a sense of adventure, and in a very real way, a kind of a pioneering feeling. . . . It really touched my heart deeply that we should be privileged to be involved with this great work, and that’s how we felt. It was a sacred privilege, a sacred trust.”[12]

William E. Berrett personally accompanied the Madsens to Great Britain to meet with local priesthood leaders and introduce the new program. They immediately met with the leadership of the Glasgow, Manchester, Leeds, and Leicester Stakes. Madsen recalled Berrett’s influence on the local leadership: “President Berrett was masterful in dealing with these wonderful priesthood leaders. He was a man who looked like a prophet, and who had the bearing of true patriarch. . . . These marvelous brethren listened as he described what the systematic study of the gospel would do for their young people, and without hesitation or question, these presidencies would unanimously and immediately say, ‘Oh, yes, that’s what we want.’”[13] Local leaders hungered for some kind of religious education for their youth, and Berrett’s regal presence undoubtedly helped smooth the reception of the program.[14]

Berrett flew home from England just over a week after arriving with the Madsens. Watching Berrett depart, John Madsen remembered his feelings: “As [Berrett] flew out of sight we suddenly felt the full weight of the responsibilities, and challenges that were ahead.” Remembering some of the last instructions Berrett gave, Madsen felt overwhelmed by the responsibility he was about to undertake. “President Berrett had indicated that the success, the future success of the educational program of the Church rested squarely on the reception of this program by the leadership in the British Isles. If we failed in this mission, we would set the Church program back at least ten years.”[15]

With strong support secured from the local leadership, Madsen at once set to work to organize the first class. As he began, one of his biggest worries came from the lack of materials. Madsen recalled: “The thing we were anxious about was that the curriculum had not even been written yet. It was still in the process of being written and printed. So we had nothing to take with us. We had no samples of what we were going to be doing. Rather, we just had a concept and were assured that by the time the first classes started in October, the materials would be in our hands.”[16] Madsen later recalled, “To get the first major shipment, I had to go down to the London Heathrow Airport and virtually walk those seminary supplies through the customs process, because they said these materials were illegal.” [17] The British customs officials told him only materials printed inside the country were allowed. Madsen continued: “I had to convince them, by some miracle, to allow these religious materials to be used in an educational program that only involved and benefitted their British people. It was a challenge that made me feel like Moses before the Pharaoh, because they weren’t going to budge and it was against their regulations, and it was strange and foreign to them. But somehow, they finally yielded and allowed me to bring those materials in.”[18] Despite the challenges, the seminary program successfully launched in Britain sooner than expected.

Madsen soon found that the local leadership felt such enthusiasm for the program that they wanted to bypass the home-study model and begin early-morning classes, despite the challenges of travel. The first seminary class in Great Britain convened at 7:00 a.m. on August 19, 1968, in the Glasgow Ward of the Glasgow Stake in Scotland, only fifteen days after John Madsen’s arrival in the country. The first teacher was Arthur Herbertson, a member of the Glasgow Stake presidency, with nineteen students attending.[19] Within a few weeks, home-study work began. The first series of monthly meetings for home study, dubbed “Super Saturdays” by the local membership, were held in October.[20] As word of the program spread, enrollment grew. Madsen reported: “The initial enrollment efforts resulted in 237 home-study seminary students, with 97, 79, and 61 students in the Leicester, Leeds, and Manchester Stakes, respectively. Enrollment in early morning seminary totaled 80 students, 26 of whom were in the Glasgow Stakes, along with 54 in the London Stake.”[21] Madsen later noted, “The universal complaint, voiced by parents and leaders when they heard the program described and saw samples of the materials was, ‘why can’t we have seminary too?’”[22]

A few of the first seminary students in Britain near Major Oak in Sherwood Forest.

A few of the first seminary students in Britain near Major Oak in Sherwood Forest.

New Countries and New Challenges

With the first classes outside of North America under way, preparations began to bring the program to more countries. The first classes after those in Great Britain were held in Australia beginning in 1968 and were followed the next year by courses in New Zealand. Berrett sent several teachers to England, Australia, and New Zealand to follow up on early successes and spread the program into new areas. Plans began to take Seminaries and Institutes to non-English-speaking nations, but the difficulties involved in translation of materials delayed the start of these programs. In 1970, three teachers were chosen to launch the programs in Guatemala, Brazil, and Uruguay.[23]

Some of the first seminary students in Britain at the Dudley Zoo.

Some of the first seminary students in Britain at the Dudley Zoo.

Even with two years of experience at this point, there was still a feeling that the teachers being sent out were flying on a wing and a prayer. Robert Arnold, bound for Guatemala, remembered his orientation with Berrett before his departure: “I called William E. Berrett and made an appointment and drove clear down to Provo to the administration building on BYU campus. I went in and sat down and I said, ‘Hello, I’m Bob Arnold and I have been asked to go to Guatemala and I was just wondering if you could give me some instructions as to what you want us to do?’ He said, ‘Well, go down and start seminary, and use the Book of Mormon, of course.’” When Arnold pressed Berrett further, the only answer he received was, “Just go down and do what needs to be done. We won’t leave you stranded.” Arnold recalled, “That was the end of the interview. That was the total orientation I had about Latin American seminary.”[24]

The next few years brought a new series of adventures to the Seminaries and Institutes family set against a global backdrop. The teachers sent out to launch the programs worked tirelessly to get the programs started regardless of environmental challenges, long distances, and even political instability. In Brazil, David A. Christensen and his entire family of four slept on a single mattress, their only piece of furniture, for a month and a half until funds could be wired to solve the problem.[25] In the Philippines, Stephen K. Iba paid his driver twenty extra pesos to drive through a flood in order to reach the pier where the teaching materials waited. When the car was swamped, Steve Iba, in his white shirt and tie, jumped out to push, while his wife, clutching a baby, stood on the seat of the car to escape the water rushing in. They were finally rescued by several Filipino boys, each of whom received ten pesos for their trouble.[26]

In Guatemala, Robert B. Arnold, a Church Educational System (CES) coordinator, was accosted by government soldiers for duplication equipment found in his house. The soldiers assumed the equipment was being used to print antigovernment propaganda, until Bob Arnold explained he was a Mormon setting up an educational program. The lead soldier replied, “You’re Mormons? I have a niece who is a Mormon,” and moved on to the next house.[27]

Establishing Guidelines for Global Expansion

In 1970, William E. Berrett and Ernest J. Wilkinson retired, and Neal A. Maxwell took over as the new Church Commissioner of Education, appointing Joe J. Christensen as the new head of Seminaries and Institutes. The new leaders soon recognized the infeasibility of running the program with just American teachers indefinitely, and they soon established a set of guidelines for the teachers sent to an international assignment. Given a three-year time limit, the teachers sent around the world were tasked with accomplishing three objectives: “(1) Develop a positive working relationship with priesthood leaders. (2) Start the home-study seminary program, enrolling interested secondary and college-age students. (3) Find and train a person who could provide local native leadership, thus removing the necessity of exporting others [teachers] from the United States.”[28]

With these guidelines in place, the focus of international Church education began to shift from the exploits of the American teachers to the search for and then decades-long work of their native replacements. After 1975, the placement of American teachers to launch S&I programs in other countries became rare, as CES leaders began recruiting indigenous educators to head up the new programs.[29] The recruitment of these native instructors also began the formation of a network of teachers and leaders moving the Church toward a more truly global perspective.

Finding Indigenous Teachers: E. Dale LeBaron and Donald Harper in South Africa

An illustration of the transition from a program led by North Americans to one relying on local leadership is found in the work of E. Dale LeBaron and Donald Harper in South Africa. LeBaron was an institute teacher in Alberta, Canada, when he was asked to return to South Africa, the country where he had served as a missionary eighteen years earlier. He wrote in his journal, “Like most missionaries, I yearned to someday return to the land and people I learned to love as a missionary, but when I made the decision to go into Church education for a living I gave up that hope. I did not feel my dreams could be realized on a Seminary-Institute salary.”[30] Now returning, he brought along a wife, Laura, and six children, ranging from eleven years of age to just eighteen months.

Dale and Laura LeBaron and their family stopped in Jerusalem while traveling to South Africa to launch the first seminary and institute programs in Africa.

Dale and Laura LeBaron and their family stopped in Jerusalem while traveling to South Africa to launch the first seminary and institute programs in Africa.

LeBaron’s dreams soon turned to nightmares as the family was beset by an unusually intense set of difficulties. A shipment containing many of the family’s personal belongings was broken into and looted. Adding insult to injury, soon after this, the family’s car was broken into and several more valuable items taken. During a family trip to the beach, LeBaron’s daughter Debra was swept out to sea. As he attempted to rescue her, both LeBaron and his daughter nearly drowned before a pair of local surfers intervened to rescue them. While the attention of the family was fixed on rescuing both father and daughter, the LeBarons’ youngest son, David, found a bottle of prescription medicine in his mother’s purse and swallowed nearly all of its contents.[31] The little boy soon fell into a coma and was saved only through prompt medical attention and administration of a priesthood blessing.[32]

These misfortunes reached their peak on January 20, 1973, the day the Seminaries and Institutes program officially launched in South Africa with its first monthly meeting in Capetown. On the return trip, LeBaron, traveling with his wife and two of their children, got in an accident with a flatbed truck, completely destroying the family’s car.[33] Frazzled from this series of unfortunate events, the LeBarons immediately flew to Johannesburg to request a blessing from the mission president serving in the country. LeBaron remarked stoically, “This near tragedy was one of many instances in a sequence of events brought by some unseen power to interfere with or prevent the establishment of the great Church Education program to bless the youth of South Africa.” He continued, “Following that blessing, we were never troubled further with any similar instance or problem and we felt a release from a destructive influence.”[34]

The work began to proceed more smoothly, and LeBaron was soon successful at completing the most important of his duties: finding a replacement. The man he recruited, Donald Harper (who was LeBaron’s former missionary companion), soon began accompanying LeBaron on his rounds throughout the country, learning through observation. Though both were enthusiastic Latter-day Saints, the two men were a study in contrasts. LeBaron came from pioneer stock and was a lifelong member. Harper was a convert at the age of twenty, introduced to Mormonism through the basketball games played at a chapel near his home.[35] While LeBaron dreamt of returning to South Africa, Harper had dreamt of leaving and coming to America.

A decade before the arrival of the first seminary programs in South Africa, Harper and his new bride, Milja, had traveled to America, visiting every temple in the country via Greyhound bus. While visiting Church headquarters, the Harpers had the opportunity to meet with Elder Harold B. Lee of the Quorum of the Twelve. When the couple informed Elder Lee of their desire to immigrate to the United States, the Apostle looked directly at them and replied bluntly, “Brother Harper, we don’t need you here. You go back to South Africa and help build up the Church there and you will receive the desires of your heart.”[36] Reluctantly, the Harpers returned home. Ten years later, Harper was approached by LeBaron, who asked him to take over as the CES director for South Africa.

Harper was trained for a year before the LeBarons departed. He left a successful career in the restaurant industry to take the position. Overwhelmed at first by his responsibilities, he later said, “I felt at the time, ‘Why me?’ I failed to meet the qualifications of a full-time CES personnel person. But I think that, in retrospect, they were looking more for somebody with administrative skills to be able to hold the program together.”[37] The Harpers took up the challenge not only to build the CES program, but to act as quiet agents of positive social change in their own society.

Witnessing the injustices of apartheid in their native country, Brother and Sister Harper worked to encourage black and white members of the Church to attend meetings together. One of the fondest memories held by the Harpers from their work in CES came when they invited a mixed group of black and white young single adults to attend a conference in Swaziland.[38] When a regional conference was held in South Africa, with Apostles Boyd K. Packer and Howard W. Hunter in attendance, Brother Harper requested that the institute provide a mixed choir, with black and white students. His wife, Milja, acted as the choir director, leading the mixed choir at a time when the Church was still dominated by white membership. Brother Harper commented: “The most significant thing that I saw in that experience was, at that age group, you could create that mixing and the unity. I could not have asked for an adult choir that achieved having a third of it black. It’s the younger generation that makes it happen. For them, they are totally color blind now.”[39] He also remembered that “President Hunter, from his chair, turned around, and shook every one of those 164 choir members’ hands.”[40] Enjoying a fruitful career spanning several decades, the Harpers stayed in their native land filling numerous roles for the Church in their professional and ecclesiastical service. In 1985, true to the promise given by Harold B. Lee, the Harpers at last gained access to all the blessings available in America with the dedication of the Johannesburg South Africa Temple.

Cultivating Local Leadership: Rhee Honam and South Korea

The established pattern of sending Americans to establish the gospel began to come to a close with the establishment of CES programs in South Korea. When L. Edward Brown, who was serving as an instructor at the Pocatello Idaho Institute, was called to be mission president in South Korea in 1971, Associate Commissioner Joe J. Christensen approached him with the proposal that he encourage the beginning of seminary and institute there. When President Brown arrived in the country, he began working to establish the programs. CES had originally decided to send a returned missionary to begin the program, but President Brown pointed out that there were Korean priesthood holders who were capable of teaching. He recommended Rhee Honam as a teacher. In the 1950s, Brother Rhee joined the Church, beginning a long, faithful life of service. At the time he was approached to teach in CES, he was a professor of English and Spanish at several universities in Seoul. It was not an easy decision to change careers.[41]

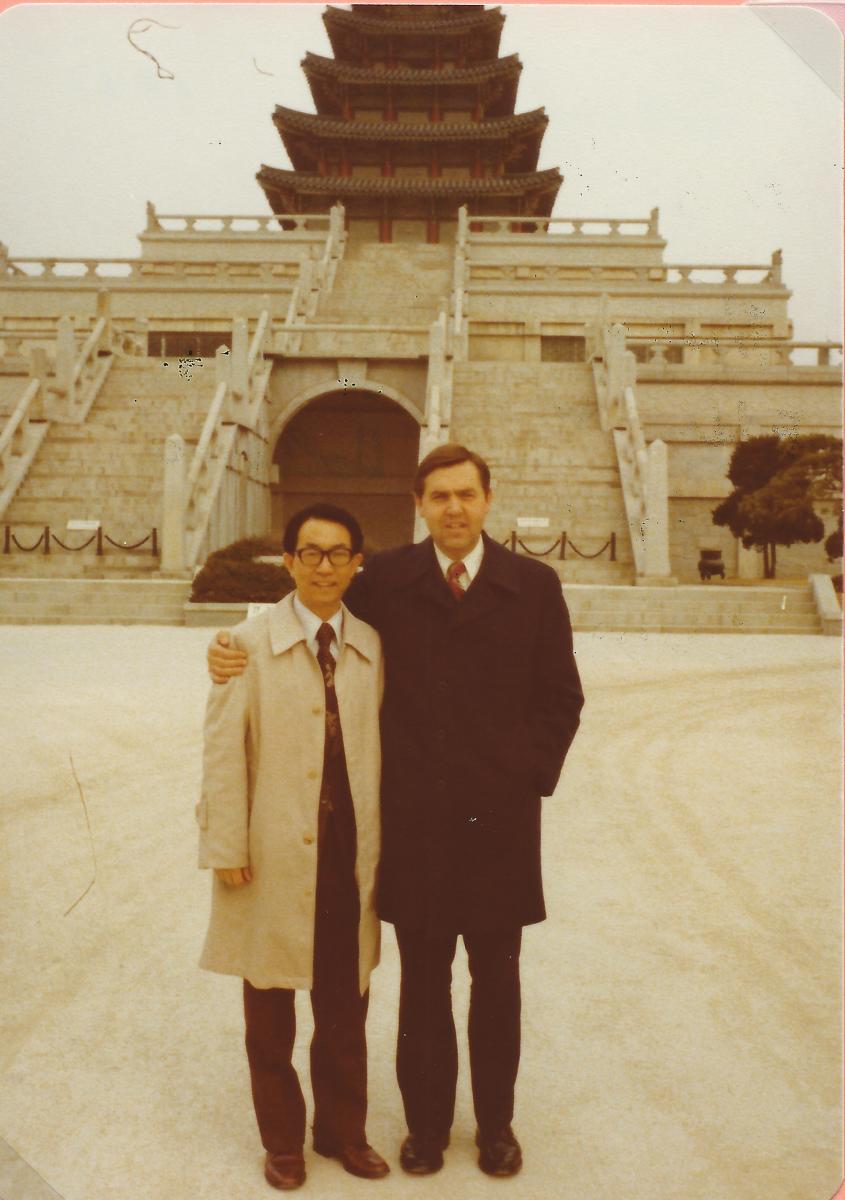

Rhee Honam with Church Commissioner of Education Jeffrey R. Holland.

Rhee Honam with Church Commissioner of Education Jeffrey R. Holland.

Communication with Salt Lake was slow, and Brother Rhee didn’t know if he was hired or not. Finally, President Brown, confident that CES would employ Brother Rhee, opened an office for him at the mission home. Brother Rhee quickly went to work and hired several teachers, including Pak Byung Kyu, who later became the area director. Classrooms for institute were leased in a building in downtown Seoul. The students were delighted to be able to take classes there, and attending was considered a prestigious opportunity. When the first graduation was held in the mid-1970s, the valedictorian was a member who already had a doctorate and taught philosophy in the university.[42]

Rhee recalled that the greatest challenge to the seminary program was nonmember parents who were concerned that home-study seminary would take away time from preparing for high school and college entrance exams. Rhee invited the parents to visit the seminary class and explained how important it was for their children to have religious education to blend with the secular things they were learning.[43]

In his report for the 1972–73 school year, Rhee said that many adult members in Seoul took institute, and their experience resulted in their enrolling their children in seminary and institute. Church activity also increased and youth were encouraged to serve missions. That year there were twenty-three converts from the S&I classes.[44]

Speaking of the importance of using native teachers in the work, Rhee later said: “The Lord blessed me with this program because I’m a Korean and I know the cultural background and the mentality, and I was in the educational field for years, along with my leadership position in the Church. Surprisingly, everybody supported me. I think I had complete support from both the members and leaders.”[45] Not only an educational pioneer, Brother Rhee was also called to serve as the first stake president in South Korea in 1973, and in 1978 he became the first native Korean called as a mission president.[46]

Rhee Honam’s ecclesiastical service illustrates another vital contribution of CES programs to the worldwide development of the Church. In a religion with lay clergy, the recruitment of indigenous teachers allowed for the development of strong local leadership in the Church. Like Rhee Honam, the majority of the men recruited to head the programs locally served as bishops and stake presidents, as well as in a multitude of other callings. Their professional work allowed them to study the gospel and serve in the Church full-time. CES was (and still is) considered a profession and not a calling within the Church, but the nature of the work allowed Church units in developing areas to have a quasi-professional clergy without actually having a professional clergy. When asked to address the high number of CES personnel called into ecclesiastical leadership, Neal A. Maxwell commented, “We found able local leaders for seminaries and institutes. Then, as the Church matured, the Brethren would come in and call them as the stake presidents. I finally ended up with some criticism. ‘How come our CES men end up as the stake presidents?’ I said, ‘Brethren, we were there first. We didn’t come along and pick stake presidents. You picked seminary and institute people as stake presidents.’”[47]

Becoming a Global System

The new global programs brought change to their respective nations, and they also fundamentally changed the nature of Church education itself. The administration at Church headquarters was just as affected by the new global programs as the membership they served. No administrator better captures the formation of this global organization than Frank Day.

Frank Day served as an administrator for Seminaries and Institutes. When Joe J. Christensen decided to divide administrative duties along geographic lines, Day was chosen to administer to one of the worldwide zones created. Remembering his experiences fighting against the Japanese in the Pacific during World War II, Day privately feared that he would be assigned to Asia. He later said, “I had been in the Orient in the military as a Marine and I had been trained that the enemy was the Japanese. The Marines trained well—not only how to use weapons, but how to hate the enemy. And I suspect that that was part of the reason, or maybe the main reason, I didn’t want the Orient.”[48] In fulfillment of his fears, the following day Brother Christensen assigned Brother Day to supervise Asia and the South Pacific.[49]

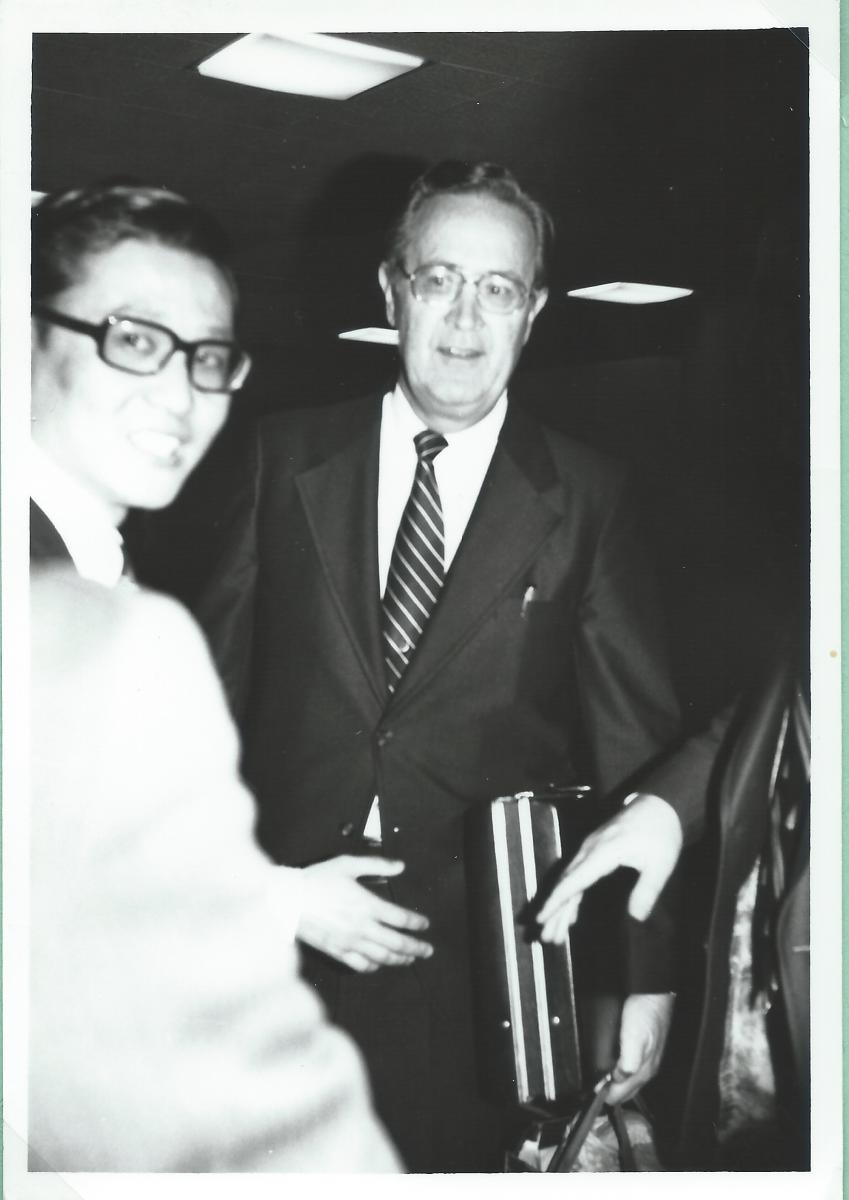

Frank Day and Sheldon Poon in Hong Kong in 1978.

Frank Day and Sheldon Poon in Hong Kong in 1978.

As the day of his first trip to Asia approached, Day continued to be filled with anxiety. Arriving in Okinawa, the site of one of the bloodiest battles Day fought in, he still had no idea how he would respond in his upcoming meetings. He arrived at the airport and was met by a Japanese member of the Church. Day later recalled what occurred next: “As I took two or three steps toward the mission president, the Japanese brother, it was one of the most unusual experiences I think I’ll ever have, because in a matter of seconds, the bitterness and the hatred, the training and the fear of years, was suddenly eliminated. I stepped up and it was the most natural thing in the world to put my arms around Brother Kan Watanabe, the mission president. He put his arms around me and all of the hatred was gone.”[50]

During his service as zone administrator over Asia, Brother Day traveled extensively throughout the region, visiting countries along the Pacific Rim. He was instrumental in the locating and hiring of dozens of teachers and administrators in CES programs. Not only did Day feel that his work as an administrator removed his hatreds and prejudices, but he also saw how it built bridges between former adversaries, creating a brotherhood irrespective of national boundaries. Brother Day inaugurated a series of conventions designed to build relationships among the CES personnel and their families. During his tenure, meetings were held in New Zealand, Australia, Hong Kong, Korea, and Japan. He vividly remembered one meeting held in Osaka, Japan. Day later recalled: “The history of Japan and Korea has not been a history that has run smooth. Japan controlled Korea for forty-seven years. They would not allow them to use their language, made them take Japanese names, and they were not above killing. So there was a great deal of animosity and even bitterness between the two people. But at this meeting, Brother Rhee [Honam] from Korea, spoke excellent Japanese as well as Korean, and he was able to help our Japanese brethren who did not speak English that well.” [51]

Looking over the meeting, Day reflected on the remarkable collegial atmosphere of the gathering, continuing, “They were working together, sitting together at the table. The feeling of love and respect and unity was so strong that when the meeting was over, these two brethren, one Korean, one Japanese, put their arms around each other and expressed their love for each other and their gratitude for the help they had received from each other during the convention. I felt that if we could do no more than bring people together and let the spirit of the Lord work on them, whatever else they learned would be worth it.”[52]

“Trying to Contain an Explosion”

The stories shared here only represent a small part of the international expansion of Latter-day Saint religious education programs. Just one decade after the first class began in England in 1968, seminary and institute programs existed in forty-five different countries.[53] Over forty years later, these programs are found in over 160 different nations, nearly every place where the Church has a presence. The expansion was so rapid that Commissioner Maxwell said, “Being over the expansion of Seminaries and Institutes was like trying to contain an explosion.”[54] For all the different factors that might have gone wrong, so much went right that it was clear to the individuals involved that the Lord was leading the way. Joe J. Christensen commented on this remarkable group of teachers, some who were willing to leave their homes to launch the program, as well as those chosen from among the local cultures to continue on as the standard bearers of the programs: “The circumstances just came together with certain people who had the ability. They were in the right place at the right time to do the job, and had the commitment to do it. Many of them could have been in other assignments or professions that would be much more lucrative. They have been absolutely dedicated to building the program.”[55] The leadership developed by CES is only a small part of the international expansion of the latter-day Church, but it remains a vital part of the superstructure of global Mormonism.

Notes

This study was the final project in the life of Dale LeBaron. His wife and oldest daughter requested that if any of this material was used that he be given credit as coauthor.

[1] Sources for this study come primarily from the work of E. Dale LeBaron, a professor in the Department of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University from 1986 to 2000. During the 1990s, LeBaron began a project to collect oral histories from the American teachers sent out during the international expansion of Church education during the 1960s and ’70s. He subsequently conducted over forty-five different interviews with administrators and teachers who took part in these events. His work was never published, and LeBaron passed away in 2009. As part of a project sponsored by Seminaries and Institutes, Casey Paul Griffiths compiled these interviews, along with supporting documents, and worked to collect a second round of interviews with teachers recruited around the globe to permanently teach and administer these Church education programs. See Casey Paul Griffiths, “The Globalization of Church Education” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 2012). Material in this study was also utilized in the volume By Study and Also by Faith: One Hundred Years of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2015).

[2] A note on the use of oral histories in this study: Most of the interviews used in this study were carried out by E. Dale LeBaron during the early 1990s, along with several oral histories carried out by others in the following decades. Because oral histories may sometimes be unreliable, contemporary documents, including CES records, have been utilized (whenever possible) to correlate the events described in this study. However, many of the stories related here only exist in the interviews referenced, and an absolute certainty of all the details involved cannot be achieved.

[3] For a history of the origins of seminary, see Brett D. Dowdle and Casey Paul Griffiths, “A Godsend for the Salvation of Modern Israel,” in Joseph F. Smith: Reflections on the Man and His Times, ed. Craig K. Manscill and Brian D. Reeves (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2013). For a general history of the seminary and institute programs, see Casey Paul Griffiths, “A Century of Seminary,” Religious Educator 13, no. 3 (2012).

[4] David O. McKay Diary, 20 April 1961, David O. McKay papers, MS 668, box 46, folder 5, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah.

[5] Delbert L. Stapley to Gordon B. Hinckley, December 11, 1964, Salt Lake City, Church Educational System administrative files, CR 102 125, box 10, folder 8, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL).

[6] Lt. Col. A. E. Haines to William E. Berrett, September 1, 1963, New York, NY, CES administrative files, box 10, folder 10, CHL; emphasis and punctuation in original.

[7] A report on the worldwide educational needs of the Church during this time indicated the start of four seminary classes at American military bases in Heidelberg and Frankfurt, Germany, and Zama and Tachikawa, Japan. This information is contained in J. Elliott Cameron, “A Survey of Basic Educational Opportunities Available to Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” 3 vols., unpublished report, 741, copy in Griffiths’s possession (hereafter Cameron Report).

[8] Cameron Report, 743. It should be noted that Berrett’s visit to Europe occurred immediately after the infamous episode of “baseball baptisms” that occurred in the late 1950s and early 1960s. For a more detailed look at this period, see Gregory A. Prince and William Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005), 227–55. Berrett himself referred to these problems in a 1991 interview with E. Dale LeBaron: William E. Berrett, interview with E. Dale LeBaron, May 6, 1991, 5–6, copy in Griffiths’s possession.

[9] For a more extensive history of the development and pilot test of home-study seminary, see Donald Wilson, “History of the Latter-day Saint Home Study Program,” unpublished manuscript, MS 4941, CHL; and Jonathan E. Thomas, “The Worldwide Expansion of Seminaries to English Speaking Countries from 1967–1970” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2011).

[10] John Madsen interview, August 8, 1991, interviewed by E. Dale LeBaron, manuscript in Casey Paul Griffiths’s possession, 16; Derek A. Cuthbert, The Second Century: Latter-day Saints in Great Britain, Vol. 1, 1937–1987 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 129–30.

[11] William E. Berrett, A Miracle in Weekday Religious Education (Salt Lake City: Salt Lake Printing Center, 1988),162–63.

[12] Madsen interview, 40.

[13] Madsen interview, 43.

[14] Madsen interview, 45.

[15] Madsen interview, 40.

[16] Madsen interview, 36.

[17] Madsen interview, 74.

[18] Madsen interview, 72.

[19] John Madsen, “A Brief Account of the Introduction of the Church Education Program in Great Britain,” unpublished document, 4.

[20] Madsen, “A Brief Account,” 4.

[21] Madsen, “A Brief Account,” 5.

[22] Madsen, “A Brief Account,” 3.

[23] The three teachers selected to launch the programs in Latin American were Robert Arnold (Guatemala), David A. Christensen (Brazil), and Richard M. Smith (Uruguay). E. Dale LeBaron conducted oral history interviews with each of these teachers in 1991, copy in Griffiths’s possession).

[24] Robert and Gwenda Arnold interview, May 2, 1991, interviewed by E. Dale LeBaron, 6–7, copy in Griffiths’s possession; emphasis added.

[25] See David A. Christensen interview, May 9, 1991, interviewed by E. Dale LeBaron, 25.

[26] See Stephen K. Iba interview, June 26, 1991, interviewed by E. Dale LeBaron, 25, copy in Griffiths’s possession; Church Educational System Division Histories, 1946–1974, Tonga and Phillipines, box 4, folder 4, CHL.

[27] Robert B. Arnold interview, May 2, 1991, interviewed by E. Dale LeBaron, 12, copy in Griffiths’s possession.

[28] Joe J. Christensen, “The Globalization of the Church Educational System,” in Global Mormonism in the 21st Century, ed. Reid L. Neilson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2008), 191.

[29] Cory W. Bangerter was sent to Portugal in 1979 as the last professional religious educator sent to launch a program outside of the United States. See E. Dale LeBaron, “Go Ye into All the World: Pioneering in Church Education,” 3, unpublished manuscript, Seminaries and Institutes research library. In the late 1980s, CES began programs to send CES missionaries, usually retired couples, to locate and train new CES directors in different areas around the world. See By Study and Also by Faith, 354.

[30] E. Dale LeBaron, “Historical Details Relating to the Introduction of Seminary and Institute to South Africa and Rhodesia,” unpublished document, date unknown, 1, copy in author’s possession; Church Educational System Division Histories, 1946–1974, South Africa, box 4, folder 2, CHL.

[31] Debra Sue LeBaron St. Jeor interview, 27 November 1992, interviewed by E. Dale LeBaron, 10, transcript in author’s possession.

[32] LeBaron, “Historical Details,” 11.

[33] St. Jeor interview, 10.

[34] LeBaron, “Historical Details, 11–12.

[35] Donald and Milja Harper Oral History, interviewed by Jeffrey L. Anderson and Casey P. Griffiths, 16 September 2010, 1, The James Moyle Oral History Program, CHL.

[36] Harper Oral History, 34.

[37] Harper Oral History, 29.

[38] Harper Oral History, 169–70.

[39] Don and Milja Harper, phone conversation with Casey Paul Griffiths, October 25, 2011, notes in author’s possession.

[40] Harper Oral History, 167.

[41] R. Lanier Britsch, From the East: The History of the Latter-day Saints in Asia, 1851–1996 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1998), 193.

[42] Britsch, From the East, 193–94.

[43] Rhee Honam Oral History, interviewed by E. Dale LeBaron, June 28, 1991, 28, CES International Expansion Files, CR 102 368, CHL.

[44] Rhee Honam, Annual report for 1972–73, Church Educational System Division Histories, 1946–1974, box 3, folder 6, CHL.

[45] Honam Oral History, 25–26.

[46] See Spencer J. Palmer, “Rhee Honam: Hallmarks of an International Pioneer,” in Pioneers in Every Land, ed. Bruce A. Van Orden, D. Brent Smith, and Everett Smith Jr. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1997), 68.

[47] Neal A. Maxwell 1991 Oral History, interviewed by E. Dale LeBaron, March 3, 1991, copy in Griffiths’s possession, 11.

[48] Frank D. Day Oral History, interviewed by David J. Whittaker, July 22, 1977, OH 366, 16, CHL (hereafter Day 1977 Oral History).

[49] Day 1977 Oral History, 16.

[50] Day 1977 Oral History, 17–18.

[51] Frank Day 1991 Oral History, interviewed by E. Dale LeBaron, May 3, 1991, copy in Griffiths’s possession, 36–37.

[52] Day 1991 Oral History, 36–37.

[53] Seminaries and Institutes of Religion Annual Report for 2013 (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2013), 3.

[54] Neal A. Maxwell interview, March 3, 1992, interviewed by E. Dale LeBaron, copy in Griffiths’s possession.

[55] Joe J. Christensen interview, 13 April 1991, interviewed by E. Dale LeBaron, copy Griffiths’s possession.