The Adolescent Brain and the Atonement: Meant for Each Other, Part 2: The Rescue

Mark Butler and Genevieve L. Smith

Mark H. Butler and Genevieve L. Smith, "The Adolescent Brian and the Atonement: Meant for Each Other, Part 2: The Rescue," Religious Educator 17, no. 2 (2016): 162–99.

Mark H. Butler (Mark.Butler@BYU.edu) was a professor and marriage and family therapist in the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University when this article was published.

Genevieve L. Smith was a graduate of the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University when this article was published.

The spiritually awakened teen's anguish over recurring stumbling can be crippling. Through spiritually sincere teens and young adults will, like Nephi, occasionally stumble and sorrow over the persistence of the natural man,... their faith in Christ can turn doubt to hope and lead them to rejoice.

The spiritually awakened teen's anguish over recurring stumbling can be crippling. Through spiritually sincere teens and young adults will, like Nephi, occasionally stumble and sorrow over the persistence of the natural man,... their faith in Christ can turn doubt to hope and lead them to rejoice.

Abstract

In consequence of the acute developmental experiences and challenges of adolescence (described in a previous paper), nearly all teens will stumble over their mortal weaknesses. For youth who have awakened spiritually and are sincere in their desires to walk uprightly and live righteously, this stumbling can be devastating. For some teens, stumbling can even introduce a spiritual “death spiral”—toxic shame, failure and fatalism, despair and depression. These feelings may, all too easily, lead to self-inflicted isolation and alienation from the spiritual support and succor they desperately need. Life’s developmental dilemma—the challenge of putting off the natural man—is encountered for the first time during the teen years with unique passion and pathos, anguish and torment. In the scriptures, we find the torment of the teen psyche described personally, poignantly, and instructively. Nephi, Paul, Alma the Younger, Enos, and others narrate the stereotypical experience and pathos of the spiritually awakened, sincerely striving adolescent or young adult who nonetheless falls short. More importantly, these scriptural accounts also describe their rescue from their personal spiritual dilemmas. In this paper, we discuss four main points: (1) We recap briefly the developmental collision during the teenage years and describe how the experience, though painful, can serve a divine purpose. (2) We detail the rescue available to the teen psyche that is found in proper understanding and faith in the Atonement. We see how the Atonement of Christ is perfectly fitted to the adolescent psyche and thus can prevent or resolve a spiritual death spiral. (3) We consider how parents can help prevent or rescue spiritually distressed teens from such a vicious spiritual downturn as they avoid shaming their youth and instead show love and support. (4) Finally, we discuss what teens can do for their own rescue, including developing a “marathon mentality” for their progress.

Keywords: adolescence; Atonement; brain development; development; developmental understanding; developmental patience/

The Rescue

In our first paper, we documented the head-on collision of the adolescent brain, the onset of puberty, and the process of spiritual awakening. We discussed additional complications and risks arising from a sexually saturated environment as well as the possibility of (intentional or unintentional) shaming responses from adults. This collision was illustrated by the story of Caleb, a spiritually awakened, sincere, striving teenager who was brought to his knees in anguish over his recurring relapses to mortal weakness, physical appetite, and carnal nature. We found Caleb on the stage behind his chapel, sobbing in spiritual anguish and mental torment. We saw Caleb in the beginning stages of his own spiritual “death spiral”—withdrawing from Church activity, distancing himself from familial support, and beset by overwhelming feelings of helplessness and hopelessness. Caleb’s experience finds expression in the words of a different young man who wrote the following after he stumbled over his mortal weakness yet again:

Dear Mom, I’m so sorry about what you are going to hear. I messed up, broke my promise to you and your trust. I hate myself for it and I think it is too hard for me to conquer. Sincerely, [name withheld]. P.S. I am sorry. I hate myself for my problems.[1]

Letter from a teenager to his mother.

Letter from a teenager to his mother.

Advances in the scientific understanding of brain development enhance our understanding of the developmental changes and challenges of puberty. This understanding has wide-ranging implications for our developmentally appropriate expectations of our teens, our responses to teen behavior, and the developmental help we provide for their behavioral, emotional, psychological, and spiritual growth and well-being.[2] Most importantly, we need to understand the teen psyche, and we need to comprehend and convey to our teens the perfect fit of the Atonement of Jesus Christ to their developmental collision—spiritual awakening colliding with the teen brain and the onset of puberty. In this second paper, our invitation to parents and leaders is to consider the urgency and spiritual imperative of conveying the doctrine of Christ to our teens and helping them apply the Atonement continuously[3] to their developmental experience in order to move forward in faith, hope, patience, and joy while working toward their divine potential and meeting the challenges of mortal life.

Young men and young women need to view their challenges in developmental perspective and their spiritual situation more realistically in light of the Savior’s Atonement and the covenant of His grace they entered into at baptism. As we saw in our first paper, life is a developmental experience. The Atonement of Jesus Christ was meant for life’s developmental journey. The Atonement was meant for our lost and fallen condition here in mortality; it is perfectly built for our developmental journey toward exaltation. It is therefore critical that we understand the Atonement’s perfect fit to the developmental experience of adolescence and apply it with compassion and understanding.

Heroes from the scriptures offer our youth what may amount to excerpts from their personal journals, so to speak, so that we might see both what life is like without the Atonement and, conversely, how joy, happiness, peace, and patience are rescued through the Atonement. We begin this article by reflecting on how the accounts of these scriptural heroes depict a common experience of spiritually sincere youth struggling with tendencies to which the adolescent brain is prone and acute weaknesses of the teen and young adult years. As we find rich representation of the teen psyche in the scriptures, therein we will also find redemptive answers.

Both scriptural and modern-day narratives will illustrate the concepts we discuss in this article. First, we discuss the accurate depiction of the teen psyche in the scriptures, enabling teens to liken unto themselves the experience of their prophet heroes. Next, we consider that the collision between the spiritual awakening and the mortal weaknesses of the teenage years may be divinely planned. We then discuss how parents can be part of the plan as they help teens understand the challenging developmental reality of adolescence and how the Atonement is the perfect solution to this psychological and spiritual collision. Finally, building on that spirit, we then consider how we can help our youth as we (1) steer clear of shame, (2) instill a marathon mentality for mortality, and (3) provide opportunities for teens to stretch themselves and extend their development through “doable” interval training and goal-striving.

Finding the Teen Psyche in the Scriptures

Caleb is not alone. We hear Caleb’s lament and sorrow echoing from the distant past in the words of Nephi—spiritually sincere and striving, yet nearly despairing of ever overcoming his weaknesses:

Behold, my soul delighteth in the things of the Lord; and my heart pondereth continually upon the things which I have seen and heard.

Nevertheless, notwithstanding the great goodness of the Lord, in showing me his great and marvelous works, my heart exclaimeth: O wretched man that I am! Yea, my heart sorroweth because of my flesh; my soul grieveth because of mine iniquities.

I am encompassed about, because of the temptations and the sins which do so easily beset me.

And when I desire to rejoice, my heart groaneth because of my sins. (2 Nephi 4:16–19; emphasis added)

And in the words of Joseph Smith, thinking back on his own adolescence:

Being of very tender years . . . I was left to all kinds of temptations; and . . . I frequently fell into many foolish errors, and displayed the weakness of youth, and the foibles of human nature; which, I am sorry to say, led me into divers temptations, offensive in the sight of God . . . . not consistent with that character which ought to be maintained by one who was called of God as I had been. . . .

In consequence of these things, I often felt condemned for my weakness and imperfections. (Joseph Smith—History 1:28–29, emphasis added)

Finally, describing fallen man’s inherent fallibility and inability to obey God’s law perfectly—and his subsequent spiritual turmoil—the Apostle Paul writes tellingly and poignantly of feelings which are similar to those that many youth experience; his account renders a view of the tormented teen psyche:

And the commandment, which was ordained to life, I found to be unto death. . . .

The law is spiritual: but I am carnal, sold under sin.

For that which I do I allow not: for what I would, that do I not; but what I hate, that do I. . . .

Sin . . . dwelleth in me. . . .

In me (that is, in my flesh,) dwelleth no good thing: for to will is present with me; but how to perform that which is good I find not.

For the good that I would I do not: but the evil which I would not, that I do. . . .

I delight in the law of God after the inward man:

But I see another law in my members, warring against the law of my mind, and bringing me into captivity to the law of sin which is in my members. O wretched man that I am! (Romans 7:10, 14–15, 17–19, 22–24; emphasis added)

We may also detect elements of the teen psyche and similar experiences of spiritual anguish and psychological torment in the personal accounts of spiritual awakening disclosed for our benefit by Enos (see Enos 1:2–4) and Alma the Younger (see Alma 36:12–16).

Whatever exact words various scriptural figures used to express their anguish, the words of both Nephi and Paul, “O wretched man that I am” (2 Nephi 4:17; Romans 7:24), capture the essence of the exclamation, lament, and despair of the spiritually striving teen whose spiritual awakening collides head-on with the adolescent brain and the body barraged by puberty. The words capture the tragically familiar self-deprecation and psychic anguish of spiritually sincere youth who have made mistakes.

The Prophet Joseph Smith, writing somewhat later concerning his own youth, recollects that he “often felt condemned for [his] weakness and imperfections” (Joseph Smith—History 1:29) because he was “guilty of levity, and sometimes associated with jovial company . . . not consistent with that character which ought to be maintained by one who was called of God as [he] had been” (Joseph Smith—History 1:28). Joseph’s recollection of his feelings at the time depicts a spiritually sincere, striving teen viewing himself through the exacting, demanding, limited lens of the adolescent brain, and, therefore, feeling “condemned for [his] weakness and imperfections” (Joseph Smith—History 1:29). These verses exemplify both the idealism and the perfectionism of youth (the adolescent brain’s vulnerability to extreme thinking), a by-product of which is the tendency toward harsh self-censure for every departure from perfection.

Writing of this experience from a more mature perspective, Joseph notes that he was not “guilty of any great or malignant sins” (Joseph Smith—History 1:28). A more mature Joseph is thus able to acknowledge the weakness while maintaining a sense of proportionality. Not so when he was young, though. While Joseph’s self-censure is later clearly tempered by mature perspective, at the time he was tormented with doubt.[4]

The spiritual anxiety experienced by Nephi, Joseph Smith, Paul, Enos, and Alma is commonplace among adolescents. The adolescent brain’s vulnerability to extreme thinking means that teens’ awareness of their weaknesses can easily overshadow everything else—including all the good in their lives—and can make even smaller mistakes feel large and overwhelming. Given the vulnerabilities of the adolescent brain, for adolescents the natural man casts a Goliath-sized shadow over their life: when they fall short of their ideals, teens can view themselves as lost and unredeemable.

If teens’ struggle with perfectionism in the context of imperfection isn’t moderated by redemptive faith and parental and other spiritual guidance, teens may be easily overwhelmed and discouraged and a downward spiritual spiral can ensue. Nephi’s and Paul’s despondent exclamation, “O wretched man that I am!” offers a telling depiction of the spiritually awakened teen’s desperate and depressing feelings of hopelessness when wrestling against the natural man—especially given the vulnerabilities and limitations of the adolescent brain.

Through the scriptures, we can help our teens see that they are not alone! The narratives of their hero-prophets in the scriptures show that they clearly understood the adolescent experience and psyche. We can help our teens normalize their experiences, help them see their scriptural heroes sharing in and rising above these experiences, and then study together exactly how these heroes went about it!

Collision by Divine Design?

Is it possible that this acute developmental collision during our youth, which turns us to Christ, is part of the plan to partner us with God and Christ in our spiritual journey? Though the scriptural accounts we have discussed reported feelings of inadequacy, spiritual anguish, and psychological torment that were painfully difficult, we see fortuitous fruits of those experiences. It is plausible that the acute developmental collision occurring during adolescence—the vulnerability and weakness of the adolescent brain, the coming of age of the natural man through puberty, and spiritual awakening—is divinely designed, or at least divinely employed, to help ensure that spiritual awakening is accompanied by a resolute turning toward and complete reliance upon God. Isn’t this what we saw happen with Nephi, Paul, Enos, and Alma?

It was precisely because they experienced their own complete inadequacy during their wrestle with the powerful natural man within that these mighty men turned to Christ. From their words, it seems that Nephi and Paul threw all their weight and effort at the task of being perfect—they were so spiritually sincere and zealous. However, at first they were trying to do it all on their own. When they experienced the utter futility of their personal will and work, they turned all their hope and faith to Christ.

How helpful it is that spiritual awakening is accompanied by acute experience of our weakness, so that we turn to the Lord instead of turning, Invictus-like, to the arm of flesh—our own will, discipline, and strength—as our instrumentality to exaltation. Perhaps, then, the timing of our spiritual awakening coinciding with a period of acute vulnerability and weakness is an inevitable developmental collision with the fallen man that God turns into a blessing: perhaps it is all by divine design (see Ether 12:27).

God Reaches Out to Us and Invites Us to Reach Back

There is potential divine purpose to be made from both this acute developmental collision and from our experience of weakness. In scripture (e.g., Ether 12:27), we learn that a purpose of experiencing weakness is to turn us to God for help! For many, weakness is our first point of contact with God. Through our weaknesses, God reaches out to us and invites us to reach back.

Adolescence sets us up to recognize the need for God, our Savior, and the Holy Ghost and to reach for this spiritual partnership early in our lives. The coming of age of the natural man (puberty) occurs in the same season as spiritual awakening. This ensures significant opposition (see 2 Nephi 2:11) that requires resolute determination to do battle and choose well; yet the limitations of the adolescent brain leave teens poorly equipped for the battle. The result, at best, is a stumbling progress that can turn adolescents to God for the help they need to succeed. We return again to Caleb’s life narrative to illustrate this divine design.

Earlier in his teenage years, Caleb had gone to his parents’ room early one Saturday morning and asked to talk. Caleb admitted that he wasn’t sure he had a testimony and, because of self-perceived weakness, he doubted that he would be able to be part of their eternal family. In Caleb’s words and feelings, we see the spiritual zealousness, exacting judgment, and unforgiving perfectionism of a spiritually awakened adolescent.

Caleb’s surprised parents asked him to help them understand his feelings better. Caleb told them that he had had a dream during the night that was spiritually troubling and had left him feeling anxious. Caleb’s distress at the thought of maybe not being a part of his family forever had brought him to his parents’ room—and would bring him even further. Caleb’s father remembers that his first thought was to offer quick reassurance from his parental perspective of the Atonement and of life’s paced and patient spiritual “race.” Instead, though, Caleb’s father offered a measure of comfort and then began pondering for a better answer to his son’s spiritual anxiety.

Like Joseph Smith, Caleb was not guilty of any serious sin in his early youth, but his spiritual awakening was colliding with his adolescent brain and producing an all-or-nothing spiritual perfectionism and anxiety. These are emotions similar to those Nephi felt (see 2 Nephi 4:16–19). That morning, Caleb had shared with his parents the struggles he was beginning to face. His father understood that these struggles were developmentally typical aspects of puberty that needed to be addressed with commitment, with efforts toward self-mastery, and with patience and perspective.

During the following week, Caleb’s father pondered over his son’s spiritual angst while reading scriptures and praying. One morning, during scripture study, an impression came to Caleb’s father: Father in Heaven was reaching out to Caleb through Caleb’s weakness. Caleb’s weakness was God’s initial point of contact for what could become the personal and mutually loving relationship Father in Heaven seeks with all His children. Through Caleb’s feelings of concern over his own spiritual welfare, a loving Father was reaching out to Caleb and inviting him to reach back.

It struck Caleb’s father how similar this was to the experiences shared by Enos, Nephi, and Joseph Smith. Though Caleb experienced his dream as negative and distressing, his anxiety was, nonetheless, a spiritual provocation and prompt. It could be an important beginning. Just as it had led Caleb to his parents’ room the previous Saturday, it could lead Caleb to his Heavenly Father’s “room” through prayer—just as similar anxiety had done for Enos (see Enos 1:2–5). It could begin the forging of Heavenly Father’s and the Savior’s redemptive relationship with him.

About a week after the morning Caleb had approached them, his father and mother shared these developing impressions with him. They shared with Caleb their positive sense of his experience—their commendation and their joy in his spiritual awakening, their acknowledgement that coming unto Christ shows us our weakness (see Ether 12:27), their confidence that God was not chastening or condemning Caleb but reaching out to him, and their encouragement to Caleb to “reach back.” Caleb’s parents tried to temper his feelings of anxiety and perceptions of unworthiness and refocus his attention on spiritual striving and on his budding redemptive relationship with Deity.

Our Weakness Invites Our Partnership with God

After their initial conversation that first Saturday morning, Caleb’s father had sought to comprehend the spiritual import of his son’s experience. Through scripture study and prayer during the week that followed, he discerned that this is a spiritual developmental archetype! God initiated contact with Caleb through his weakness, just as he has done with so many others. Our weakness invites our relationship and partnership with God. Alongside Caleb’s experience stand the similar scriptural accounts of Enos, Nephi, and Joseph Smith, and the personal journal accounts of many teens, whose weakness is their first point of poignant contact, communion, and vital connection with God.

Awareness of weakness attends spiritual awakening and can turn us to God (see Ether 12:27). Yet parents and leaders must be careful because teens might experience that awareness in a devastating and debilitating way.[5] Shame-prone teens are particularly vulnerable to distorting and amplifying their experiences of weakness until they fall into discouragement, despair, depression, and surrender!

As parents and leaders, we need to understand this typical teen encounter of moral weaknesses following spiritual awakening and help teens temper their tendency to respond counterproductively and self-destructively to their anxiety and dissonance. Of course we affirm spiritual understanding which helps us know that neither we nor our teens should minimize, compromise, or permissively accommodate sin—for God does not “look upon sin with the least degree of allowance” (D&C 1:31; Alma 45:16) and “no unclean thing can enter into his kingdom” (3 Nephi 27:19; Moses 6:57; 1 Nephi 10:21; Alma 11:37; Alma 40:26). Yet we need to help our teens respond to guilt not with self-shaming but with repentance! And we also need to capitalize on these experiences by encouraging teens to think of their anxiety as God reaching out to them in love. We need to help them understand that their feelings are part of a loving Father’s personal invitation into the redemptive relationship we all must have with Heavenly Father, through Christ.

Spiritually sincere teens have already embarked on the spiritual journey of coming unto Christ; when they encounter their weakness—which they will—we must encourage them to cleave unto Christ. We must teach teens to resolutely resist Satan’s temptation to run and hide upon their encounter with their fallen condition. We must make it clear that the devil’s strategy is to get us to run and hide ourselves and cover our weaknesses (see Moses 4:14) so that he can divide and conquer us!

In direct contrast, instead of hiding our weaknesses, God asks us to confess our weaknesses and then rely on Him. We all have need of the Atonement of Jesus Christ; none of us can save ourselves. Through the Atonement, we can have peace and joy, not just there and then, but here and now as we “run with patience the race that is set before us” (Hebrews 12:1). Therefore, the sooner we experience our desperate need and complete dependence on God and engage with Him on His terms of complete surrender—the only surrender that ensures victory—the sooner our journey of redemption and perfection will be spiritually underway.

This theme of personal desperation and spiritual surrender followed by peace, joy, and rejoicing through faith in Christ courses through the narratives of Nephi, Paul, Enos, Alma the Younger, and others. Caleb’s father was impressed that his son had had this same experience of weakness so that Caleb, like others in the scriptures, might embark on the same spiritual journey. Like heroes of old, teens everywhere need to be taught by their parents and leaders to see their own poignant awareness of weakness as part of the plan, like a single piece of a much larger puzzle. Teens can then capture the vision of an unfolding picture of potential and promise made possible through their faith in and reliance upon the Father and the Son, and Their divine love.

The Atonement: A Perfect Fit

By virtue of our divine nature, we inherit divine potential and are receptive to divine influence—even the light of Christ within us. Thus, divine desire is natural to us. Yet in mortality, like the prophets we have discussed, we come up hard against the weaknesses of the flesh. By divine design, mortality is a framework of opposition—the spiritual versus the carnal—and this opposition framework (see 2 Nephi 2:11) is meant for our learning and growth. This dissonance is acute during adolescence and is acutely painful for spiritually awakened, perfectionistic, shame-prone teens.[6]

Although the Atonement of Jesus Christ is needed during all of life’s seasons and the entirety of our developmental journey, at no time in our lives is the opposition framework of mortality more starkly drawn than during the adolescent years. Since adolescence is a time of piercing spiritual sensitivity and vulnerability, it is particularly vital that teens know the Atonement and its provision for their stumbling developmental progress.

How Great the Importance to Make These Things Known

We are all born into a fallen world and housed within fallen tabernacles (see Mosiah 16:3; Alma 42:10). Whatever weaknesses we each face, we all resonate with the personal spiritual struggle Nephi describes (see 2 Nephi 4:27–28). Undoubtedly, Nephi faced challenges in his youth as well. Nephi knew the importance of the Atonement to navigating all the seasons of life, including the painful dissonance of combined carnal and spiritual awakening during adolescence. Nephi also knew the perfect fit of the multifaceted Atonement of Jesus Christ to the developmental experiences and needs of spiritually sincere, striving youth (see 2 Nephi 4:16–35). Therefore, Nephi yearned for all to know the same truths that had rescued him. He thus recorded:

For we labor diligently to write, to persuade our children, and also our brethren, to believe in Christ, and to be reconciled to God; for we know that it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do. . . .

And we talk of Christ, we rejoice in Christ, we preach of Christ, we prophesy of Christ, and we write according to our prophecies, that our children may know to what source they may look for a remission of their sins. (2 Nephi 25:23, 26)

Father Lehi held the same awareness and sense of urgency as his son Nephi regarding teaching the Atonement; could it be in part from observing the experience of his son? In a like manner, Lehi taught:

And men are instructed sufficiently that they know good from evil. And the law is given unto men. And by the law no flesh is justified; or, by the law men are cut off. . . . [and] they perish from that which is good, and become miserable forever [without the knowledge, understanding, and rescue of the Atonement].

Wherefore, redemption cometh in and through the Holy Messiah. . . .

Behold, he offereth himself a sacrifice for sin, to answer the ends of the law, unto all those who have a broken heart and a contrite spirit. . . .

Wherefore, how great the importance to make these things known. (2 Nephi 2:5–8; emphasis added)

Lehi, like Nephi, wanted us to know about the brick wall of weakness every spiritually aspiring person runs into sooner or later. He juxtaposed the futility of a perfectionistic, arm-of-the-flesh reliance upon our will and work alone with the relief, joy, and success to be found in patient reliance upon the Atonement. Grace and works combined were the answer he found. Significantly, the Atonement is the answer both for making the journey and for reaching our destination.

One can imagine that Nephi shared his spiritual struggle and angst with his father. In Lehi’s doctrinal testimony of the Atonement, we might perceive a possible retrospection and connection to things Lehi had seen his son Nephi go through—like sharing with others in general conference things he had learned with his own son. Lehi’s doctrinal declaration could perhaps be an echo of loving testimony once borne to his son Nephi—the witness of both the dilemma of mortality and the rescue of the Atonement—from a time when he had observed Nephi’s spiritual struggle and angst, brought on by Nephi’s own developmental collision with mortal weakness.

Father and son, Lehi and Nephi, had both come to comprehend our mortal dilemma, and from their words it seems certain they compassionately comprehend the “teen psyche” and the spiritual torment that for some ensues—just as it had for Nephi. We speculate there was an exemplary loving, compassionate, tender spiritual relationship between father Lehi and his son, and we see in Lehi’s testimony a loving parent’s doctrinal response, caring reassurance, and heartfelt yearning for his son: “Son, the Atonement is perfectly fit to the struggle you’re facing!”

From a lifetime of ministry, we cannot doubt that Lehi knew well both the dilemma and the rescue. Thus, he urged, “Wherefore, how great the importance to make these things known” (2 Nephi 2:8). Throughout time, the experiences of believing parents with their spiritually sincere children led them to know the importance of similarly acknowledging our desperate situation in mortality and testifying of the doctrine and rescuing power of the Atonement.

The Atonement is perfectly fit to life’s developmental experience, reconciling us to God and allowing us peace and joy even while our lives are very much works in progress. Like Lehi and Nephi, Jacob and Alma the Elder also understood this need and taught their children about the redemptive power of the Atonement. Jacob taught Enos faith in Christ (Enos 1:8)—taught him to know both the “nurture and admonition of the Lord” (Enos 1:1). When young Enos’s spiritual awakening came, his “soul hungered” and he felt spiritual anxiety for the welfare of his soul, just as young, teenage Caleb did. We have already familiarized ourselves with this spiritual anxiety, the by-product of spiritual awakening occurring in the unique and trying developmental milieu of adolescence. In describing his experience, Enos records, “I kneeled down before my Maker, and I cried unto him in mighty prayer and supplication for mine own soul; and all the day long did I cry unto him; yea, and when the night came I did still raise my voice high that it reached the heavens” (Enos 1:4).

In Enos’s spiritual awakening, we see a spiritually sincere and anxious young man possessing an admirable fervor and zeal, alongside a potentially hazardous scrupulous conscience.[7] God reaches out to Enos through Enos’s weakness, and Enos, because he was taught, knows to reach back; he then finds the peace and joy the Atonement brings. However, without instruction, it could have been otherwise. Enos’s fervor and zeal could have set him up for a negative spiral as he both awoke spiritually and encountered the natural man within himself. But for the witness of the Atonement received repeatedly from his father Jacob, it could have turned out differently for Enos.

When Enos’s spiritual awakening occurred (see Enos 1:3) and he came to that piercing recognition of his weakness and need for redemption (see Enos 1:4; Ether 12:27), he knew to come to God to wrestle for forgiveness (see Enos 1:2). Similarly, in his desperate situation, Alma the Younger remembered his father speaking “concerning the coming of one Jesus Christ, a Son of God, to atone for the sins of the world” (Alma 36:17). Because their fathers—and surely their mothers, too—taught them faith in what the Atonement could and would do for them, these sons were equipped for their day of spiritual awakening and head-on collision with the natural man. For one son (Enos), the collision meant spiritual anxiety concerning the welfare of his soul; for another (Alma the Younger), it meant terrible suffering and anguish. Yet when they awakened to the reality of their condition, Enos and Alma, like Nephi and Paul, were able to “[catch] hold” (Alma 36:18) upon the testimony of Christ and reach for the lifeline of the Atonement.

In these scriptural accounts, parents can see a pattern—the necessity of witnessing to our children the doctrine and rescue of the Atonement of Jesus Christ, over and over again. Because of what their parents had taught them, the youth we’ve discussed were equipped for the day when their spiritual awakening would collide with their carnal condition and developmental reality. In the end, each could join Nephi in affirming, “nevertheless, I know in whom I have trusted” (2 Nephi 4:19).

Each relied on Christ and each was rescued from despair. No spiritual death spiral ensued for them! Each undoubtedly sorrowed for sins, but with their eyes fixed on Christ and their trust placed in God, they were steady in their faith, forgiveness, peace, and joy. Through faith in Christ, the challenges of mortality need never bring them (or us) to the brink of despair again.

Faith in Christ enabled developmental patience for their journey of redemption and exaltation. With all our Primary teaching of commandments and obedience, let us never forget the centrality of faith in Christ and a clear understanding of what the Atonement provides. Navigating the framework of opposition and testing that is mortality necessitates a knowledge of the Redeemer, knowledge that needs to be in place well before the collisions of adolescence.

Modeling Our Parenting After These Prophets

Given the developmental unfolding we have outlined, perhaps for most of us adolescence is our first experience of “view[ing ourselves] in [our] own carnal state” (Mosiah 4:2) and experiencing and wrestling with persistent enticements, temptations, and weaknesses. If we have been taught well, “[We cry] aloud with one voice, saying: O have mercy, and apply the atoning blood of Christ that we may receive forgiveness of our sins, and our hearts may be purified; for we believe in Jesus Christ” (Mosiah 4:2). Christ is our developmental answer.

Like Nephi and others, we pray for that change of heart that leaves us with “no more disposition to do evil, but to do good continually” (Mosiah 5:2; Alma 5:26; Alma 19:33; Mosiah 4:2–3; Romans 7:14–15, 17–25; 2 Nephi 4:16–21, 23–28, 30–35).[8] While youthful spiritual awakening begins this journey to develop a changed heart, reliance on the Atonement enables and empowers lifelong continuation of the journey, inspiring motivation and hope and bringing needed help. The Atonement helps us come to terms with rather than be defeated by the reality that a change of heart is a developmental and maturational process. While still miraculous, it is rarely instantaneous.[9]

In spite of normal adolescent impatience, teens can be helped to understand that the Spirit of the Lord washes over us like a wave of the sea, again and again over the years. Each time, the wave erodes and washes away a little more of the natural man, bringing that “mighty change in us, or in our hearts,” until, finally, “we [indeed] have no more disposition to do evil, but to do good continually” (Mosiah 5:2)—not just in one thing, but in many things, and finally in all things. Through the enabling power of the Atonement, we are empowered to make good on all our righteous desires.[10]

Just like parents in the scriptures, we need to make sure that our youth understand that life’s journey is an incremental developmental progression; and we need to make sure they access the comfort as well as the enabling power of the Atonement. Thereby, they can gird themselves for this spiritual exodus requiring patience and persistence, of which Israel’s long forty-year journey is an apt symbol. Parents, having experienced firsthand life’s developmental journey and the gradual process of sanctification, are able to compassionately teach, comfort, and assure youth concerning life’s developmental progression and the importance of being patient with ourselves even while we remain diligent (see Mosiah 4:27).

Parents and leaders need to turn to the scriptures and, together with our youth, read the accounts of Nephi, Paul the Apostle, Enos, Alma the Younger, Joseph Smith, and more. We need to discover together their experiences and their journeys. Another scriptural account applicable to the adolescent predicament is when Moses beheld God’s glory and creations and God addressed him three times with the words, “my son,” and the inspiring assurance, “thou art in the similitude of mine Only Begotten . . . [who] is full of grace and truth” (Moses 1:6). Moses’s vision gave him humility (see Moses 1:10) combined with an inspiring, invigorating, and compelling vision of his possibilities (see Moses 1:6, 7, 13, 16, 40), which motivated and strengthened him to resist temptation.[11] A compelling vision of their divine potential, combined with a full understanding of the reach and scope of the Atonement, can instill in our youth a fighting spirit and an empowering faith. These together will give them a fighting chance.

Every youth needs a mentor concerning Christ and His Atonement to help them through the acute developmental intersections of adolescence. Parents’, leaders’, and adolescents’ developing personal witness and comprehension of the Atonement helps enable safe and successful navigation through the teen years. Without these, developmental perspective and patience may be lost on our youth (and possibly on parents and leaders, too). In that situation, teens’ lives could become overshadowed and overwhelmed with despair, despondency, and feelings of failure.

Picture in your mind a skinny, gangly adolescent going to war against a Goliath giant, and you have a pretty accurate picture of the adolescent brain in relation to the natural man—outmatched. Only the power of the Atonement can make up the difference in size and strength. For that battle, our children need to be armed like David of old, with faith in the Lord. Thus, “we talk of Christ, we rejoice in Christ, we preach of Christ” (2 Nephi 25:26).

What We Need to Preach: The Partnership of Grace

So, what elements of faith in Christ and the Atonement do we need to be sure to share with our youth? We ought to help our children understand that, while perfection is the goal, God and Christ are patient and compassionate mentors.[12] Fruits of the Atonement include peace, patience, and power for repentance. That power is both a cleansing power and an enabling power.[13] We must teach our children the partnership of grace, how to partner with God and with Christ.

God is loving, patient, and insistent. “God is love” (1 John 4:8), and the Father and the Son want to forgive[14] and help us.[15] When we teach of the Father’s and the Son’s love and compassion, we teach our teens to refuse Satan’s divide-and-conquer lies—his attempts to persuade them that they are not worthy of God’s help, that weakness or relapse foreclose on grace, or that they have to attain some minimal benchmark of virtue before God will hear them or help them. Given the perfectionism and black-and-white extreme thinking to which the adolescent brain is vulnerable, all too common are their beliefs that, “God won’t hear my prayer now!” or “I have to repent first, then God will hear my prayer.” However, what those teens don’t realize is that repentance is what prayer is for! And what grace and the Atonement are for! Father in Heaven always wants us to pray, no matter what we have done wrong, and, through prayer, to access grace and the Atonement because of what we’ve done wrong:

Never believe that you are not worthy to pray and cannot turn to God and Christ for help. That is the most diabolical lie of all, and so utterly and absolutely untrue, considering all God and Christ have already done for us! Your loving Father in Heaven and Savior, too, have given everything for your repentance and redemption and will not forsake you now. Satan gains no greater victory than when he succeeds in separating [a young man like Caleb] . . . from the outstretched arms of the Lord and loving others. [We must teach our teens to] reject every divide-and-conquer ploy [of the Adversary].[16]

As parents and leaders, we must make sure that we, too, are there for our teens with outstretched arms—not with shaming disappointment, criticism, or blame.

Spiritually sincere teens often equate recurring relapses with personal hypocrisy; they don’t give themselves credit for the authenticity of their righteous desires, intents, and striving in the face of a long and difficult war. They also frequently fail to take into account the developmental reality of mortality. Furthermore, they are usually completely unaware of the unique limitations and challenges of their adolescent years

Clearly, the idea that God doesn’t help the sinner—including a son or daughter who is in the beginning stages of learning—is patently absurd! (e.g., Matthew 7:7–11). The sinner is precisely who Christ came to help! (Mark 2:17). Heavenly Father wants each of us to accept and apply the Atonement of Christ both for developmental patience and so we can one day return to Him and find joy in His presence: “God sent not his son into the world to condemn the world; but that the world through him might be saved” (John 3:17). The Atonement is not just for the power to repent and perfect our lives—though that is a central, sanctifying, and exalting purpose. The Atonement is also to provide peace, patience, and joy for the journey. In every age, these truths have been reflected in prophets’ invitations to repentance, compassion, and mercy. Prophets and apostles extend these invitations in our day as well.[17] Teens might consider these words from Elder D. Todd Christofferson, noting and combining God’s compassion, condescension, and command:

It is God’s will that we be free men and women enabled to rise to our full potential both temporally and spiritually. . . . I am under no illusion that this can be achieved by our own efforts alone without His very substantial and constant help. “We know that it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do” (2 Nephi 25:23). And we do not need to achieve some minimum level of capacity or goodness before God will help—divine aid can be ours every hour of every day, no matter where we are in the path of obedience. But I know that beyond desiring His help, we must exert ourselves, repent, and choose God for Him to be able to act in our lives consistent with justice and moral agency. My plea is simply to take responsibility and go to work so that there is something for God to help us with.[18]

The refreshing and comforting news we can share with our teens is that the Atonement of Christ makes it possible for God to help us all the way, every day.[19] Heavenly Father does not hold back until we somehow “earn” or “deserve” His blessings. We only need to qualify for His help by desire and by effort—our works meet for repentance. Then God can and will help us the rest of the way. Mercy steps in on the condition of our repentant heart and ongoing labors.

Lifting the weight of sin from our lives will be hard, and we must offer every ounce of our strength to the task (2 Nephi 25:23) and then trust that, through the enabling power of the Atonement and divine grace, God and Christ will make whatever strength we have sufficient (see Ether 12:27; 1 Corinthians 10:13). Again, parents can help teens take heart in both the enabling power and the patience, peace, and joy for the journey the Atonement brings.

Parents need to remember that the adolescent brain doesn’t readily “get this.” The mentality of the spiritually sincere, striving teen who is struggling with the adolescent brain’s propensity to perfectionism is to condemn himself or herself for his or her fallen nature and persistent struggle—and to believe that everyone else, including God, does too.

Teens need to be helped to comprehend God’s overwhelming love. Teens’ experience of Christ’s Atonement ought to be and can be the exquisite experience of God’s love (see Alma 38:8). In part, this will come as parents and leaders model God’s love in the ways they act toward and respond to their teens. Our relationships as well as our teachings need to bear witness of the love of God—the reason and means by which the Atonement was wrought. Though there are conditions to forgiveness, parents can help teens comprehend God and Christ in terms of Their fatherly and sacrificial love—an infinite, open-arms love that is quick to forgive and commands repentance for our good. Parents need to understand and counter teens’ natural tendency to project their own harsh perfectionism onto God with the subsequent risk of teens feeling as alienated from God as they do from themselves. Teens can learn to resist the adolescent brain’s tendency toward emotional reasoning[20]—which trends toward “un-reasonable” extremes of self-judgment and self-censure, with attendant feelings of alienation and isolation. Instead, they can learn to keep faith in the love of God and hope in themselves.

Getting and keeping possession of our hearts. Teens also need to be taught to resist emotional reasoning and not give up hope in themselves or their ideals; they need to know that God rewards the righteous desires and virtuous intents of our hearts.[21] Getting and keeping possession of their hearts—even in the face of setbacks—is perhaps teens’ first and most critical developmental task.

Teens are prone to emotional reasoning. If they feel like they’re failing, they are vulnerable to surrendering both the fight and their faith. Parents and leaders can help teens who are wrestling against the strength of the natural man and working to train their brains: we can help them to believe and feel that because of the Atonement of Christ, the desires of their heart matter right alongside their unfolding development and improving behavior. The Lord counsels us to “seek the face of the Lord always” (have our hearts right) “that in patience ye may possess your souls,” and promises, “and ye shall have eternal life” (D&C 101:38). Getting and keeping possession of their hearts is something spiritually sincere teens can do and need to be encouraged to focus their attention on—even in the face of discouragement—for doing so will sustain their repentance resolve and labor and lead to positive progress in developmental due time as both spirit and body gain strength for self-mastery. With patient persistence, they can overcome the natural man and take possession of their souls. In the meantime (and always), they must hold on to their hearts!

Teaching the relation of grace and works. While teaching our teens about the abundance of grace and mercy, we need to help them understand the critical connection between works and grace. We might wish and even pray for our weaknesses to be miraculously removed, but that would defeat the plan and resemble Satan’s counterfeit proposal,[22] which, in violating moral agency, was a failed idea from the beginning.

The eternal plan of redemption—God’s design for our ongoing joy, and exaltation—grows out of the entwined roots of grace and works. Nephi explained the relationship between grace and works when he wrote, “it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do” (2 Nephi 25:23).[23] Our works are essential, not to “earn our ticket to heaven,” but to qualify for the power of the Atonement in our lives and the grace that does grant us entrance—through mercy and enabling power, qualifying us for exaltation.

A spiritually motivated teen wants to “bulk up” and “get strong.” Christ is his or her “spotter.” A spotter doesn’t lift the weight for you; you would never build strength that way. Imagine if we simply reclined on the weight bench while our spotter, from above, took care of all the strengthening reps and sets. This is not the way weightlifting, or grace, works. Rather, a spotter requires all that you can do the whole way through. Throughout the “lift,” the spotter is always there encouraging and helping us just enough as we strain against our weakness and gradually turn weakness into strength. When all our strength is still not enough, we are met by God’s rescuing reach and lift. That is how we overcome our weakness and become as He is. Teens understand that a physical conditioning and strengthening program is a developmental exercise requiring time, patience, persistence, and diligence—even in the face of fatigue.

Understanding life’s lifting experience the same way helps teens approach the challenge with a greater measure of patience and helps them ease off on their self-censure. Understanding life’s lifting experience as we do weightlifting also helps us understand why God can’t, or won’t, abrogate our agency and simply take care of the lift for us. We couldn’t grow and become strong that way. Thus, Elder Russell M. Nelson counsels:

Each one who resolves to climb that steep road to recovery must gird up for the fight of a lifetime. But a lifetime is a prize well worth the price.

This challenge uniquely involves the will, and the will can prevail. Healing doesn’t come after the first dose of any medicine. So the prescription must be followed firmly, bearing in mind that it often takes as long to recover as it did to become ill. But if made consistently and persistently, correct choices can cure.[24]

Christ doesn’t shame us for what we can’t lift yet, but He always urges us to do a little better than we did before. God’s plan is to make us strong; God and Christ are already strong; and They will add Their strength to our best efforts.

Parents and leaders can help teens understand that God “gets it.” He understands life’s developmental journey and our experience of mortal weaknesses. Indeed, He designed and we chose this experience so that we can learn to know the good from the evil, tasting the bitter that we can know the sweet. He knows that we will fall short, again and again. After all, “falling is what we mortals do,”[25] but the Lord will forgive “again and again”[26] as we continue to fight on. President Uchtdorf said, “As long as we are willing to rise up again and continue on the path toward the spiritual goals God has given us, we can learn something from failure and become better and happier as a result.” [27] The Lord Himself assures us all, “As often as my people repent will I forgive them their trespasses against me” (Mosiah 26:30; Moroni 6:8).[28] Through the Atonement, He has prepared the way for our righteous desires and repentance labor to be answered with forgiveness (justification) (see Mosiah 26:30; Moroni 6:8) and with enabling power to ultimately put off the natural man and become like God (sanctification) (see Mosiah 3:19).

God knows. He understands. By means of the probationary period of mortality, He has made room for the reality that “putt[ing] off the natural man and becom[ing] a Saint through the atonement of Christ” (Mosiah 3:19) is a lifelong developmental undertaking.[29] Parents and leaders can help teens understand and feel that, while the Lord’s hopes for us are high, He is patient, and He is not stingy with His love or mercy along the way. The Lord’s compassion and generosity are abundantly illustrated throughout the scriptures. The “Savior wants to forgive,”[30] and the Lord will abundantly reward the righteous desires of our hearts as well as our repentance labors as He patiently works with us.

Spiritually sincere teens struggle to achieve congruence between their behavior and their moral ideals; we must help them find spiritual, emotional, and psychological refuge and safety in the Atonement of Christ. This is not permissiveness; it is a sanctuary from the storm. Parents, teachers, and leaders can provide the comforting witness of God’s love and His plan, leading teens to a place where they too can declare as Nephi, “nevertheless, I know in whom I have trusted” (2 Nephi 4:19).

All in all, as parents and leaders, our first line of defense on behalf of our youth is our personal witness of the Atonement and its grace in our lives, couched in the narrative, doctrine, and testimony of the scriptures and in the narrative of our own lives. Our testimony and teens’ understanding of God’s grace, patience, and love, and of His perfect knowledge of and preparation for all that they go through, can help instill a fighting spirit, temper it with patience, and give them a fighting chance.

Mirroring the Atonement of Christ and His Compassion to Our Teens

The scriptural chronicle of the Savior’s life and the testimony of the prophets concerning Him converge in witness of the Savior’s infinite love, tender mercy, and rescuing orientation to those who sin but sincerely desire to repent. The Savior said, “Yea, and as often as my people repent will I forgive them their trespasses against me” (Mosiah 26:30; see Moroni 6:8). Our lives and our interactions with our teens can mirror the Atonement of Christ and His compassion. Beyond giving a verbal witness of Christ’s Atonement, our teens need our relationships with them to mirror Christ’s compassion, mercy, and parental love.[31] As it has been said, a disciple will “preach the gospel always and, if necessary, use words.”[32] Our words and all our actions and reactions need to convey Christ and the hope and promise of His Atonement.

Steering Clear of Shaming Interaction

Mirroring Christ’s encompassing love might first involve some time in front of the mirror, observing our countenance when we feel disappointment with our teens’ weaknesses, keeping a close eye out for shaming expressions of all kinds. Shaming is close kin to condemning, which Christ deliberately avoided when dealing with the sincere and repentant. During His earthly ministry and through His atoning sacrifice, the Savior showed that He came neither to condemn nor to shame us but to save us (see John 3:16–17). The repentant always received Christ’s compassion, encouragement, and help: “Neither do I condemn thee: go, and sin no more” (John 8:11).

In our first paper, we discussed the potential for parents’ and leaders’ responses to adolescent shortcomings to exercise a shaming influence—even unintentionally—thereby exacerbating teens’ own self-torment. Since the spiritually awakened adolescent brain is prone to perfectionism, extreme black-and-white evaluation (including self-evaluation), and globalizing and generalizing, teens are vulnerable to harsh self-judgment and prone to thrash themselves over every weakness. Teens target themselves, not just their behavior. They readily see themselves as completely and irretrievably deficient. They engage in emotional reasoning: “I feel bad, therefore, I am bad.”

Consequently, even unintended signals of disappointment, displeasure, and dismay from parents or others can trigger a veritable cascade of shame in some teens. Any show of discouragement or loss of confidence lands like a heavy blow on their self-esteem and self-efficacy; they doubt they will ever overcome and become all that they aspire to be. Teens’ spiritual awakening can easily come to seem less than welcome when it triggers painful (seemingly unresolvable) dissonance and toxic shame.[33] Some are tempted to resolve dissonance and shame by denying spiritual awakening and pushing that feeling out of their lives, hardening themselves against the painful prick of conscience. An exaggerated dissonance and toxic shame readily tempt this counterproductive course of action.

Shame isolates and alienates. Shame is a significant risk factor for setting up a spiritual death spiral, just as it had for Caleb. Hence the importance to show forth “an increase of love” all the time toward teens, since they already—sometimes constantly—feel so reproved within themselves for their weaknesses and shortcomings (D&C 121:43).[34] Parents and leaders need to help teenagers experience themselves as beloved children of Father in Heaven. All mortals make poor choices from time to time, but that does not change the fundamental truth of their divine heritage. Compassion and confidence, not shame, invite repentance. Possibly, parents’ and leaders’ own all-or-nothing thinking and perfectionistic expectations need to give way to developmentally appropriate ones.

In order to mirror Christ and the hope of the Atonement to our youth, we must check our countenances in the mirror—both literally and figuratively. When we call to repentance, we need to invite and beckon, encourage and inspire. “Go, and sin no more” (John 8:11) ought always to be shared in a tone conveying abundant confidence, encouragement, and faith—in our teens and in Christ. Spiritually sincere teens, already wrestling with the adolescent brain and the challenges of puberty, are a package that we mark with the words, “Contents fragile and breakable—handle with care!”

Mentoring Teen Guilt and Spiritual Angst: The Feeling of Our Infirmities

Another part of resisting shaming is countering it when we see it in our teens. Alongside parents’ and leaders’ compassion and caution concerning shame, a teen’s own all-or-nothing thinking needs to give way to nuanced developmental comprehension of mortality’s experience and journey. Although feeling discouraged is natural when we have made mistakes, Elder Neal A. Maxwell taught that, we need to help our teens “distinguish more clearly between divine discontent and the devil’s dissonance, between dissatisfaction with self and disdain for self.”[35] This distinction can lead to a more helpful experience of appropriate guilt, an emphasis on growth perspective, and a rejection of shame’s attack on identity.[36] Spiritual mentors’ reassuring and abiding witness of the love of God and His developmental patience helps teens reject crippling, debilitating, self-destructive shame and keep striving.

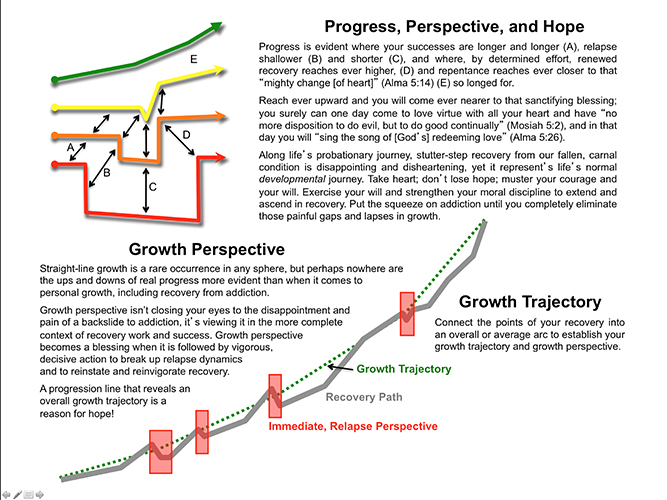

Caleb’s self-judgment, “Until I can get rid of this problem, I’m just a failure,” needs to be replaced with growth perspective (see figure 3).[37] Shame’s crushing influence should no more be self-inflicted than inflicted by others. Perfectionism and self-reproach, potentially disastrous in their impact,[38] need to be countered with growth perspective and patient faith.

Growth perspective for life's developmental journey.

Growth perspective for life's developmental journey.

As President Dieter F. Uchtdorf counsels, we need to teach our teens to have a positive relationship with themselves, not a punishing one:

It may seem odd to think of having a relationship with ourselves, but we do. Some people can’t get along with themselves. They criticize and belittle themselves all day long until they begin to hate themselves. . . . Learn to see yourself as Heavenly Father sees you—as His precious daughter or son with divine potential.[39]

Parents and leaders are thus positioned to mentor teen guilt and spiritual angst—“the feeling of our infirmities” (Hebrews 4:15).[40] Foremost, that means remembering that the purpose of suffering for sin (including guilt) is repentance, not penance or punishment.[41] Any desire we parents or leaders have, arising from impatience and frustration, to act out our own aggravation on our teens must be purged! Suffering—including guilt and godly sorrow—is conscience pain only meant to produce a U-turn to repentance—it’s not for either teens or others to work out their frustration. Beyond that, as Elder Maxwell taught, suffering is more likely to serve a devilish rather than a divine purpose.[42] Decades of research on motivation for change in addiction recovery converge with revelation in confirming essential truths about how we motivate change or repentance.[43] In the words of change process researchers Miller and Rollnick:

A certain folk belief seems to be embedded in some cultures and subcultures: [namely, that] change is motivated primarily by the avoidance of [pain]. If you can just make people feel bad enough, they will change. [So you] punish undesired behavior. . . . [The belief is that] people would be motivated to change . . . [if they felt] enough discomfort, shame, guilt, loss, threat, anxiety, or humiliation. . . . In this view, people don’t change because they haven’t yet suffered enough. Instead, constructive behavior change [comes] . . . when the person connects [change] . . . with something of intrinsic value, . . . something cherished. Intrinsic motivation for change arises in an accepting, empowering atmosphere that makes it safe for the person to explore the . . . painful present in relation to what is [deeply] wanted and valued.[44]

Miller and Rollnick also explain the following: “Humiliation, shame, guilt, and angst are not the primary engines of change. Ironically, such experiences can even immobilize the person, rendering change more remote.”[45]

Parents and leaders have traveled this road and know the terrain of life and its developmental course and progression; thus, they have the opportunity and stewardship to mentor teen guilt and spiritual angst in accordance with the example of Christ, the inspired words of prophets and apostles, and the scientific revelations of psychological and behavioral science and therapy. The spiritually sincere teen is typically already chastened enough by his or her own hyper-vigilant conscience.[46] Our ministry is to “lift up the hands which [already] hang down” (Hebrews 12:12) and strengthen them, establishing their vision of virtue and confirming their faith in Christ and in their own divine nature, desire, and potential!

Open Lines of Communication, Lifelines to Safety

By avoiding shaming our teens, by monitoring and mentoring for a helpful guilt, and by fostering faith, parents and leaders help keep lines of communication open and spiritual alliances intact. This defeats the Adversary’s divide-and-conquer stratagem. No matter how long, distressing, and sometimes frustrating the struggle can be for everyone involved, we must resolutely resist giving shaming responses to teen weaknesses. Instead, we must offer abundant reassurances of divine nature, divine potential, and divine help. Most important is our witness of the Atonement and all that great sacrifice affords us.

Unlike some youth, Caleb had shared his struggle with his parents. That Sunday at church, Caleb’s father knelt beside him, wrapped his arms around him, and just held him. He sensed that what his son needed most right then was love. Counseling together later, father and son decided, “We are not going to shame or torment ourselves for being weak, being human, and having struggles.” Caleb’s father helped him understand that they couldn’t condone sin or take a permissive, dismissive stance; yet their faith in Christ could encourage them that while the war they were fighting might be long and drawn out, they would ultimately win! Together!

Caleb’s father also shared repeatedly that the Church is for struggling saints who are striving to do better and to be better. As has been expressed, “the Church is like a big hospital, and we are all sick in our own way. We come to church to be helped.”[47] Furthermore, President Uchtdorf has taught that the Church is a place to heal and overcome our weaknesses, not hide them.[48]

“Just look around you!” Caleb’s father would say, “Who do you see that doesn’t still have some improving, some repenting to do?” Caleb decided he was going to come in with his family at the beginning of sacrament meeting and stay until the end. In the weeks and months that followed, Caleb’s family rallied around him and worked to help him keep guilt in repentance perspective[49] (see Alma 42:29) and fight off the shame that leads to self-loathing. As another part of his repentance labor, Caleb began attending LDS Addiction Recovery Program 12-Step meetings.

A Marathon Mentality for Mortality

Recovery is not going to happen all at once. We need to help teens see their own progress—even though they are not overcoming the natural man overnight. The impatience of youth needs to be tempered by perspective: putting off the natural man is a lifetime labor, not a onetime event, however much youthful impatience leads them to want it to be and try to make it otherwise. In their efforts to help teens, adults can reflect on their own developmental progress, remembering and sharing that it took time for them to be able to lift that weight. Adults can share how they built up their strength over time, in order to reach the point where they are today.

Parents’ and leaders’ own patience will help the recovering teen work for steady improvement over time and appropriately pace his or her expectations. Just as adults need to have developmental patience with teenagers, teenagers need to have developmental patience with themselves. All involved need to remember that patience, peace, and joy for the journey are made possible through Christ and His Atonement.

Developmental Accommodations: Interval Training

Wise parents and leaders grasp that just as a runner in training gradually builds stamina and strength for going longer and longer distances, so also teens can build spiritual strength and stamina over time through practice. One way we sustain hope, motivation, and a willing spirit during spiritual training is by establishing attainable repentance benchmarks and intervals (goals).

Developmental understanding can lead to critical developmental accommodations that fit expectations to capacity, such as the length of time and effort required before strengthening blessings and privileges can be enjoyed.[50] Achievable incremental benchmarks are particularly important for adolescents, given the short time-horizon of the teen brain. Because of the Atonement, we can fit expectations to capacity. Expectations that are within reach are inherently encouraging and renew motivation, resolve, and effort. Importantly, developmental allowances for the “short haul” encourage and strengthen teens for the “long haul”! Incremental goals are part of a marathon mentality—we don’t focus attention and resolve on having to run the entire 26.2 miles, but rather our next waypoint goal, which we match to our current stamina. Especially during tough times, setting our sights and projecting our will and agency just a little way into the future (e.g., “just make it to the next . . .”) is critical to ultimate success.

Developmental perspective also brings into view the reality that stamina and strength are built up over time—the teen brain gets stronger with each positive exertion—and performance improves in increments. The words and witness of prophets, apostles, and other general authorities that we have cited help us realize that the Atonement makes such developmental patience and accommodation possible, allowing us to be refreshed for life’s stretching journey with hope-sustaining rewards all along the way. These rewards include increased companionship and fruits of the Spirit (Galatians 5:22): peace, joy, spiritual communion, and other blessings and spiritual privileges. Part of a marathon mentality is a patient focus on, and acceptance of, incremental gains.

The Atonement’s allowance for developmentally appropriate expectations and progress is God’s grace embodied for repentance. This is how grace looks in overalls, at work in people’s lives, in everyday applications that parents and leaders can be a part of. Grace is no mere abstraction; it is divine condescension and appropriate accommodation for life’s developmental journey, made possible by the Atonement of Christ. Grace enables inspired, developmentally appropriate expectations and allows for patience and forgiveness, “again and again.”[51]

The brain is strengthened just like the body, through exercise.

The brain is strengthened just like the body, through exercise.

Marathon Spiritual and Mental Stamina

Adolescence is our introduction to the reality that “the race of life is not for sprinters running on a level track. The course is marked by pitfalls and checkered with obstacles.”[52] Cross-country running on an uneven course with all sorts of obstacles requires a special mental stamina. So, too, does life’s cross-country experience.

In the midst of mortality’s inevitable stumbling, we can get worn down. We can be worn out with the daily struggle to live up to high moral ideals. We can be worn down by repeated mistakes despite righteous desires, sincere intent, and (almost) uninterrupted effort. We can sometimes feel like our righteous striving is in vain. C. S. Lewis understood this same kind of weariness that Nephi and Paul expressed, how some are worn down by the chronicity of the natural man within us:

You have time itself for your ally [a senior devil tells a junior devil]. . . . The routine of adversity, . . . the quiet despair . . . of ever overcoming the chronic temptations with which we have again and again defeated them . . . all this provides admirable opportunities of wearing out a soul by attrition.[53]

Adolescents in particular are not quite prepared for this experience and can easily become discouraged. The spiritually sincere teen can be worn down by the struggle and the constant exertion required. Continuing to adhere to high moral ideals and to struggle to overcome weaknesses despite the persistent enticements of the natural man represents a marathon experience, requiring tremendous spiritual stamina and staying power. We need to help teens develop marathon spiritual, mental, and behavioral stamina right alongside their natural physical stamina. Teens can be encouraged as they see that Nephi and Paul, scripture heroes, felt the same kind of frustration firsthand and found in Christ the encouragement and help to keep going!

Knowing that everyone will face different obstacles and difficulties during this mortal life and building on our witness of the Atonement and all that it offers us, we must help our teens grow into this marathon mentality for mortality. Adolescents must learn to pace themselves mentally as well as behaviorally by marking out incremental goals (described above) and setting their mental determination on within-view milestones. They must also learn to measure their success in terms of progress, not perfection.

While translating the Book of Mormon, Joseph was counseled by the Lord to pace himself: “Do not run faster or labor more than you have strength and means . . . to enable you . . . but be diligent unto the end” (D&C 10:4). Given the importance of the Restoration, divine impatience would not have been unimaginable or implausible. Yet the Lord accommodated human limitations, urging combined patience and diligence (see also Mosiah 4:27). In the important work of saving and exalting His children, God is equally patient. We need to accept, too, that the pace of progress may be different for each of our children or youth.

In life’s race, sometimes what we are doing is correct enough; we simply need to patiently persist—not for just a little while, but throughout our lives.[54] Paul writes about the marathon of life and how we must “run with patience the race that is set before us” (Hebrews 12:1). Elder Maxwell invites us to consider that “Paul did not select the hundred-yard dash for his analogy!”[55] Along with its enabling power, the Atonement makes this developmental patience possible and allows for peace and joy throughout life’s race, not just waiting for us at the finish line. With that assurance, anchored in understanding of what the Atonement does for us, adolescents can turn attention to faithful striving rather than driving themselves and demanding from themselves an immediate successful finish (Hebrews 12:2). Parents and leaders need to encourage teens to continue to act upon their spiritual awakening with persistence and patience. The marathon mentality our teens must develop focuses on progress, not perfection:

[We regularly need to] contemplate how far we have already come in the climb along the pathway to perfection; it is usually much further than we acknowledge, and such reflections restore resolve. . . . We can allow for the reality that God is still more concerned with growth than with geography. . . . This is a gospel of grand expectations, but God’s grace is sufficient for each of us if we remember that there are no instant Christians.[56]

It is heartening to realize that the Lord cares more about our direction than our current position. Parents and leaders need to lead the way in focusing on progress, not perfection and then encourage teens to see and do the same.

Correct understanding of all the Atonement has made provision for and was meant to provide for us—including developmental perspective, patience, and accommodation—helps parents, leaders, and youth together adopt the marathon mentality so essential in mortality. We can “run with patience the race that is set before us, looking unto Jesus, the author and finisher of our faith” (Hebrews 12:1–2).

Conclusion: Active Faith in the Atonement of Jesus Christ

Correct understanding of the Atonement helps us see that it is perfectly fit to life’s developmental journey—especially and critically to the acute developmental collision of adolescence. Compassionate application of the Atonement can rescue many from despair and surrender. Father in Heaven’s preparations for our developmental experience and our abiding witness of His love for us enable us to approach our challenges with combined patience and persistence. Though spiritually sincere teens and young adults will, like Nephi, occasionally stumble and sorrow over the persistence of the natural man, again like Nephi, their faith in Christ can turn doubt to hope and lead them to rejoice as they declare, “nevertheless, I know in whom I have trusted” (2 Nephi 4:19). Through faith in Christ, teens can know that their very best every day is good enough, and that their best will continue to grow. They can be inspired and invigorated as they rise daily to the challenge of life’s long and challenging trek. Such spiritually mature perspective, patience, and fortitude in one so young is exactly what we must help and hope for.

The Atonement of Jesus Christ is a focal point of our adoration and worship of Deity. It is also a practical tool, meant to be used daily. However, it is not solely the source of power to repent and perfect our lives—though that is a central, sanctifying, and exalting purpose. The Atonement is also to provide peace, patience, and joy throughout our journey. “Adam fell that men might be, and men are that they might have joy” (2 Nephi 2:25), not just there and then, but here, now, and always. A living, vital faith invites such practical application. Youth, parents, and leaders need the unity of this faith, to sustain us all in our various roles in relation to one another throughout life’s developmental journey. In a final paper, “Part 3: Works Meet for Repentance,” we explore further practical actions that parents, leaders, and teens can take as they seek repentance and recovery and apply the Atonement in their lives.

Notes

[1] Letter in Dr. Butler’s possession.

[2] Debra Bradley Ruder, “The Teen Brain,” Harvard Magazine, September–October 2008, http://

[3] Brad Wilcox, The Continuous Atonement (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2009).

[4] It is noteworthy that Joseph Smith’s adolescent exaggeration of his mortal weakness and his self-condemnation is precisely what led him again to inquire of God, seeking forgiveness and assurance concerning his standing before the Lord (Joseph Smith—History 1:29). We hypothesize that among spiritually sincere youth, while such adolescent self-censure is quite often exaggerated, as with Joseph Smith, Father in Heaven is able use the experience to draw adolescents to Him and build and strengthen their relationship and reliance upon Him. Perhaps it could even be in part divine design that adolescents experience so acutely their weakness, as it indeed helps initiate and solidify their relationship and reliance upon the Lord. The Lord is able to draw them to Him through their weaknesses (Ether 12:27).

[5] R. Gilliland, M. South, B. N. Carpenter, and S. A. Hardy, “The Roles of Shame and Guilt in Hypersexual Behavior,” Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity 18 (2011): 12–29; C. H. Miller and D. W. Hedges, “Scrupulosity Disorder: An Overview and Introductory Analysis,” Journal of Anxiety Disorders 22 (2008): 1042–58.

[6] M. H. Butler, G. L. Smith, and B. R. Jensen, “The Adolescent Brain and the Atonement: Meant for Each Other, Part 1: The Dilemma,” Religious Educator 17, no. 1 (2016): 159–85.

[7] Miller and Hedges, “Scrupulosity Disorder.”

[8] Those I (first author) have counseled professionally have often cited this scripture and then recounted that their prayers for similar miraculous, instantaneous transformation were “unanswered.” (Some few who wish for recovery only pray for it, rather than pray and work for it.) But repentance and the equation of grace (2 Nephi 25:23) require hard work, and, most often, monumental change is incremental, not instantaneous. How important it is to know that the change of heart King Benjamin’s people experienced was the culmination of a process that had been years—probably decades—in the works (Mosiah 1:11; Words of Mormon 1:12–18; Mosiah 1:1; Mosiah 2:4; Mosiah 2:31). See Bruce R. McConkie, “Jesus Christ and Him crucified,” fireside address at Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, September 5, 1976.

[9] Even in the case of such people as Alma the Younger and Paul, the future Apostle, their remarkable conversion experiences may mark less a complete transformation or change of heart and more a resolute change of direction. It seems likely there remained for them a long journey of repentance after their U-turn experience, a resurrection or rebirth of the divine within them, and a sanctification. What we see in their turnaround is repentance in their heart, to be followed by the labor of repentance throughout every facet of their lives—weaknesses to be overcome, Christlike attributes and character to be developed, meekness and obedience to learn, and so forth.