Helping Students Study the Scriptures

John Hilton III

John Hilton III, "Helping Students Study the Scriptures," Religious Educator 17, no. 1 (2016): 108–19.

John Hilton III (john_hilton@byu.edu) was an assistant professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this article was published.

"The most important thing we could do as teachers of seminary and institute students would be to connect them with the scriptures and the results of daily scripture study."

"The most important thing we could do as teachers of seminary and institute students would be to connect them with the scriptures and the results of daily scripture study."

What are the most important things religious educators can do to have a long-range effect on their students? During a training meeting for seminary and institute personnel, Elder Dallin H. Oaks made the following statement:

There are few things that a teacher can do that would have a more powerful, long-range effect upon their students’ lives than teaching them the importance of studying the scriptures, giving them that experience, letting them taste the fruit of daily scripture study. In my judgment, that would go beyond any subject that might be taught from the scriptures, except the fundamentals in the first few articles of faith. Beyond that, I think the most important thing we could do as teachers of seminary and institute students would be to connect them with the scriptures and the results of daily scripture study.[1]

Thus, while there are many important aspects of teaching in religious education,[2] Elder Oaks singled out the importance of helping students study their scriptures daily. Many teachers recognize that it is important for students to have personal scripture study and provide lessons on this topic or occasionally verbally encourage their students to engage in scripture study. While this can be helpful, it is not generally sufficient. One of the most important things we can do as teachers is help our students to not merely know about the importance of daily scripture study but to actually study their scriptures and feel the positive results that flow from such a course of action. I believe that amidst all of the things we do as religious educators (including teachers of seminary and institute, Sunday School, Young Men and Young Women, university religion classes, and so forth) we sometimes do not pay sufficient attention to how our pedagogy and overarching teaching strategies do or do not entice students to study their scriptures daily.

Over the past seven years I have been involved in three quasi-experimental studies in which colleagues and I attempted to measure the influence of classroom assignments in increasing student scripture study. One of these has been previously published; the results of the other two are shared in this present article. These studies took place at Brigham Young University and Brigham Young University–Idaho. While these teaching environments are clearly not representative of all religious classrooms, the lessons learned from these studies may have some transferability to other settings. In this brief report, I will describe the results of this research and share some personal perspectives on how religious educators can better facilitate their students’ study of scripture.

Results from Three Studies

Comparing methods of assigning reading.

The first study, published in 2010 by the Journal of College Reading and Learning,[3] compared various methods of assigning and evaluating scripture study in a required Book of Mormon class at Brigham Young University. The subjects of this study were students in five different sections (referred to as A–E) of the same course.

Students in section A were required to read thirty minutes a day, Monday through Friday, throughout the semester. Students in section B were required to set their own goals for how much time they would spend reading each day and were also required to have read specific chapters before class. In section C, students were required to have read specific chapters before coming to class. All students in sections A–C self-graded their performance with the out-of-class reading assignments. Students in sections D and E were instructed to read specific chapters prior to coming to class, but were not graded on whether or not they read these chapters.

The 504 students enrolled in these courses were surveyed toward the end of the semester to learn about the influence of their religion classes on their scripture study. The response rate was 32 percent, which is acceptable for this type of research.[4] Table 1 summarizes the results of this survey.

Table 1 Summary of Survey Results

|

Condition |

Average (mean) days read per week |

Average (mean) minutes read per day |

Average (mean) percentage of reading completed before class |

Percentage of motivation attributed to grades |

Mean percentage of time participants felt scripture study spiritually strengthened them |

|

Assigned minutes (section A: graded, n=21) |

5.8 |

28.1 |

93.0 |

28.1 |

83.1 |

|

Personal goals (Section B: graded, n=16) |

6.6 |

24.3 |

96.4 |

28.4 |

76.3 |

|

Specific chapters, reported (Section C: graded, n=29) |

5.7 |

17.2 |

88.8 |

27.34 |

80.4 |

|

Specific chapters, unreported (section D: nongraded, n=47) |

5.7 |

19.7 |

51.7 |

18.43 |

82.2 |

|

Specific chapters, unreported (section E: nongraded, n=49) |

6.0 |

18.2 |

54.4 |

16.02 |

72.9 |

|

Average |

5.9 |

20.4 |

68.6 |

21.54 |

78.6 |

While the amount of time read per day in section A versus section B was not statistically significant, the amount of time read per day for the sections that focused on time read (sections A and B) was significantly higher than sections where reading was done by chapter (sections C–E). Sections that did not grade completed readings prior to class (sections D–E) had students who were dramatically less likely to read before class. While students in graded sections attributed a higher amount of their reading to the influence of grades, there was no statistical significance in students reporting that their scripture study strengthened them spiritually based on the grading procedures used in the different sections.

These results largely bear out President Thomas S. Monson’s famous statement that “when performance is measured, performance improves. When performance is measured and reported, the rate of improvement accelerates.”[5] When students are held accountable for reading specific amounts of time rather than chapters, they spend more time reading. Perhaps the most interesting result from this study is that grading students on scripture study did not appear to negatively influence students’ perceptions of the spiritual benefits of their study. In fact, some students welcomed more focus on scripture study. One student in a nongraded section wrote, “My first-semester class required me to read half an hour a day. I really liked that because it forced me to set aside time to really study each day and not just read a quick chapter before bed if I had forgotten earlier.”

Requiring student-selected reading goals—with accountability

The second study was performed at Brigham Young University–Idaho in 2013. In this study, I, along with some extremely capable colleagues,[6] attempted to learn what would happen if students taking an online religion course were required to report reading specific chapters each week versus report on reading specific chapters and a personal study goal each week. This online course presented an excellent experimental opportunity, as the curriculum was relatively fixed, and there were minimal differentiating teacher effects as might be seen in face-to-face classes.

Six sections of Religion 122 were selected to be “treatment” groups and compared with six sections that served as “control” groups. Prior to this experiment all online Religion 122 classes were structured around students completing weekly reading assignments (e.g., Alma 36–42). Students did weekly assignments that included being graded on their answer to a question such as the following:

I have completed the reading assignment for Week Two (Alma 36–42 and Student Manual pages 232–247).

A. None of it

B. Some of it

C. Most of it

D. All of it

Students in the control group continued to receive this question as part of their weekly assignment. Students in the treatment group read quotations from prophets regarding the importance of scripture study and were invited to set and report a personal scripture study goal to their instructors. These students, in addition to receiving the previously mentioned question as part of their weekly reading assignment, were given an additional question each week. This question was the following:

How many days during this week did you complete your daily scripture study goal?

a. 0

b. 1

c. 2

d. 3

e. 4

f. 5

g. 6

h. 7

We wanted to learn whether students in the treatment group would read more than students in the control group. At the end of the semester, students in all sections (n=624) were invited to participate in an online anonymous survey (via the Learning Management System) in which they reported on various aspects of the course, one of which was the number of days that students read the scriptures each week. In total, 414 students completed the survey, a response rate of 66 percent. On average, the number of days read per week in the control class was 5.5 days per week and 6.4 days per week for the intervention group. The overall effect size was .6 (a relatively large statistical effect size for educational research). There were no statistically significant differences in how many minutes students read each day. As the first study showed, this study indicates that when students are measured on an activity and report on their progress, their performance increases relative to when they do not measure and report their work.

Requiring student-selected reading goals—without accountability

The third study was identical to the second but with one important difference. In this iteration, students in the treatment group were invited to read quotations on scripture study and assigned to set a goal for personal scripture study; however, they were never asked in future assignments to report on the numbers of days they read each week, nor were they graded on the extent to which they adhered to their goals. Other than an invitation to submit a goal during the first week of class, and a reminder of their goal during the fourth week of class, there were no differences in the course assignments between the two groups. At the end of the semester, students in all sections (n=282) were invited to participate in the same survey as those in the previous study. A total of 217 students completed the survey for a response rate of 77 percent. Students in the control group reported reading the scriptures 5.4 days per week, while students in the treatment group reported an average of 5.5 days per week, a non–statistically significant result.

In this instance, the pedagogy for the treatment group (inviting students to read prophetic quotes about scripture study and set personal study goals) was identical to the second study. However, students had no accountability for this goal—not only were they not graded on it, they were not even asked about it. It appears that as a result, they did not obtain the higher outcome achieved by students in the treatment group in the second study, in which accountability was a key aspect of the treatment design. Performance was neither measured nor reported and did not improve.

Collectively, these three studies suggest that teachers can change student behavior (in this case regarding personal scripture study) by requiring students to measure and report on it. While this seems like an extremely simple statement, I believe it has important implications for teachers in motivating their students to more regularly study the scriptures. At the same time, I acknowledge that all of these studies have significant limitations. They rely on student self-reports of data, which may be inaccurate. Moreover, they all take place in religious education settings in which students were being graded on their personal scripture study. While this practice was found to not negatively influence student perceptions of the spiritual impact of their study, it may not be a desired or feasible approach for some teachers. Notwithstanding these limitations, these studies have informed my perspective on how teachers can encourage students to deepen their personal study of the scriptures.

Personal Reflections: Six Suggestions for Helping Students Regularly Study the Scriptures

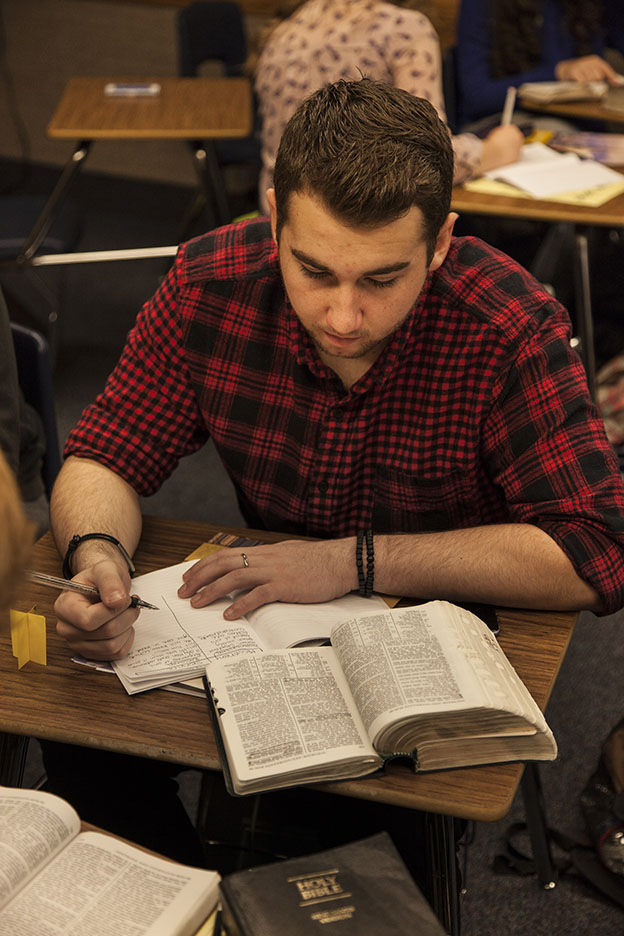

Our classrooms are among the best settings for students to practice skills that breathe new vigor into their scripture study and consequently motivate lifelong study.

Our classrooms are among the best settings for students to practice skills that breathe new vigor into their scripture study and consequently motivate lifelong study.

Utilizing my experiences with the foregoing studies and fifteen years of full-time employment as a religious educator, I offer the following six suggestions for helping students regularly study the scriptures, some of which are directly connected to the studies in which I have participated.[7] First, be seriously engaged in your own personal scripture study. When we can share up-to-date, first-person experiences regarding the blessings of scripture study, our students are more likely to see the value for themselves. This may sometimes involve stepping back from the lesson blocks we are assigned to teach to testify about our current scripture study.[8]

Second, regularly teach, model, and allow students to practice scripture study skills in class. Some students do not study regularly because they do not know how to learn from the scriptures. Simple techniques such as utilizing scripture study aids, pondering, likening the scriptures, finding principles, looking for one-liners, using http://

Third, help students exercise their agency by creating their own plan for gospel study. While assigning specific chapters or amounts of time to read may have merit, my bias is toward letting students make their own choices. In recent years I have applied this principle by providing students with selected quotations from prophets on personal scripture study. After students read these quotes, we discuss the general principles taught, and I invite students to prayerfully set their own goal regarding the amount of time they will study each day. I ask students to share their goals with me and have found that students often set goals that stretch them further than I would have, had I imposed a goal on them.

Fourth, issue a clear invitation for students to regularly study their scriptures. A basic tenet from Preach My Gospel is, “Rarely, if ever, should you talk to people or teach them without extending an invitation to do something that will strengthen their faith in Christ. . . . People will not likely change unless they are invited to do so.”[9] In extending this invitation, help students feel of its importance through sharing prophetic quotations and your personal testimony. In my case, the invitation is for my students to study the scriptures daily for the amount of time they prayerfully selected.

Fifth, provide an appropriate number of opportunities for students to report on their progress in personal scripture study. Follow-up is crucial. In some settings, part of this follow-up might be a tracking sheet in which students regularly mark the days that they read. I believe that such reporting should typically be private rather than public. Some might express concern that scripture study is a personal worship activity and should not be the subject of teacher inquiry. One potential solution to this concern is for teachers to allow students to “opt out” of such assignments and do an alternate assignment instead. This allows students to determine the extent to which they are willing to share this aspect of their lives with their instructors. In other settings, the follow-up can be less frequent. I typically have my students report on their reading twice a semester, with the first reporting period taking place three weeks after their goals are set. This allows experimentation as well as flexibility if students want to change their goal at that point. When following up on scripture study, in addition to asking about the number of days read, provide students with questions regarding how they perceive the value of their scripture study. Why are they choosing to study? Are they feeling positive fruits from their scripture study? Do they notice any patterns around why some study sessions are better than others? Providing students with the opportunity to reflect on their study may prompt important insights and help develop future metacognitive strategies.

Sixth and finally, regularly engage students both individually and collectively in discussions regarding the efficacy of their scripture study. Teachers can contact students who are not studying their scriptures and offer them personal encouragement. President Howard W. Hunter reminded teachers, “The very best teaching is one on one and often takes place out of the classroom.”[10] In addition to these vital one-on-one conversations, teachers can facilitate classroom discussions. For example, a teacher might distribute a questionnaire (in some situations this could be done electronically, outside of class time) asking students open-ended questions such as, “What is going well with your personal scripture study?” or “How could your personal scripture study be improved?” Anonymously sharing student comments can provide a springboard to vibrant discussions. For example, a teacher might say, “Several people in class wrote that they are always too tired when they study. I know I’ve faced this problem as well. Who would be willing to share some thoughts on how they tackle this difficulty?” The insights that follow could be helpful both for those offering them and for those who struggle.

Conclusion

In this brief essay I have described three research studies and shared some personal perspectives on how teachers can help their students more deeply engage in personal scripture study. My perspective is limited in that much of my professional emphasis in this area has been as a professor at Brigham Young University, which is a unique environment. There are specific techniques that might be more effective in other types of classrooms, such as Sunday School or institute. My hope is that religious educators will experiment with creative approaches, dedicate their best efforts to helping students develop habits of effective scripture study, and share their findings with others.[11] For example, a teacher recently told me of his success in having “scripture buddies” in which two students were paired together and would text each other reminders to study the scriptures. Is the efficacy of this technique merely anecdotal or anchored in evidence? I hope that future studies will be published that measure how specific interventions influence student scripture study.

Notes

[1] “A Panel Discussion with Elder Dallin H. Oaks” (Seminaries and Institutes of Religion Satellite Broadcast, August 7, 2012), https://

[2] Admittedly, a search on lds.org for “The most important thing” highlights that over time many “things” have been identified as being “the most important.” I believe that it is nevertheless significant that Elder Oaks singled out on this occasion the importance of seminary and institute teachers helping their students develop a habit of personal scripture study.

[3] John Hilton III, Brad Wilcox, Tim Morrison, and David Wiley, “Effects of Various Methods of Assigning and Evaluating Required Reading in One General Education Course,” Journal of College Reading and Learning 41, no. 1 (2010): 7–28.

[4] Kim Bartel Sheehan, “E-mail Survey Response Rates: A Review,” Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication 6, no. 2 (2001): 1–20.

[5] Thomas S. Monson, in Conference Report, October 1970, 107. A similar quotation, “That which is measured improves. That which is measured and reported improves exponentially,” has been attributed to Karl Pearson.

[6] I acknowledge the efforts of Ken Plummer, Ben Fryar, and Jacob Adams in their collaboration on the two studies performed at BYU–Idaho that are reported in this study.

[7] In sharing these suggestions, I acknowledge that my observations may not be wholly accurate, and even if they were, practices that have worked well for me may not be effective for others. Several valuable suggestions for helping students study the scriptures are found in “Study the Scriptures Daily and Read the Text for the Course,” Gospel Teaching and Learning: A Handbook for Teachers and Leaders in Seminaries and Institutes of Religion (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2012), section 2.3.

[8] In the August 5, 2014, broadcast for Seminaries and Institutes, Chad Webb said, "In order to be skillful teachers of the word of God, we must pay a price in personal study and preparation to master the content of the scriptures." Chad Webb, “An Invitation to Study the Doctrine and Covenants” (Seminaries and Institutes of Religion Satellite Broadcast, August 5, 2014). See also Preach My Gospel, 181

[9] Preach My Gospel (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004). 196, 200.

[10] Howard W. Hunter, “Eternal Investments,” Teaching Seminary Preservice Readings (Religion 370, 471, and 475) (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004).

[11] Additionally, much more is needed in terms of understanding how students study and how they perceive the efficacy of their scripture study. An excellent recent foray into this is Eric D. Rackley, “How Young Latter-day Saints Read the Scriptures: Five Profiles,” Religious Educator 16, no. 2 (2015): 129–48.