The Role of Art in Teaching Latter-day Saint History and Doctrine

Anthony Sweat

Anthony Sweat, "The Role of Art in Teaching Latter-day Saint History and Doctrine," Religious Educator 16, no. 3 (2015): 40–57.

Anthony Sweat (anthony_sweat@byu.edu) was an assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this article was published.

This article is an expanded and adapted version from an appendix in the book From Darkness unto Light: Joseph Smith’s Translation and Publication of the Book of Mormon, by Michael Hubbard MacKay and Gerrit J. Dirkmaat.

How far has Fine Art, in all or any ages of the world, been conducive to the religious life?

—John Ruskin, Modern Painters, 1856[1]

Each of the Ensign images from 1974 to 2014 is inconsistent with some aspects of documented Church history of the translation process of the Book of Mormon. For example, only one painting in the past forty-three years depicts Joseph Smith using the Urim and Thummim.

Each of the Ensign images from 1974 to 2014 is inconsistent with some aspects of documented Church history of the translation process of the Book of Mormon. For example, only one painting in the past forty-three years depicts Joseph Smith using the Urim and Thummim.

Being a Brigham Young University religion professor and a part-time professionally trained artist[2] is a bit like being a full-time police officer and a weekend race-car driver. At times the two labors are mutually reinforcing, and at others they are completely at odds. As a teacher of Latter-day Saint history and doctrine, it is extremely beneficial to have visual art represent and bring understanding to our history, and as an artist it is invaluable to have meaningful history to illustrate and provide context to messages in a piece of art. Many of the world’s most iconic pieces of art, such as Michelangelo’s Pieta or Jacque Louis David’s Marat, are visual representations of historical events. However, true art and true history rarely (if ever) fully combine.[3] They are intertwined entities (history needs to be visually represented, and artists need meaningful history to create impactful images), but their connection more often creates difficult knots instead of well-tied bows that serve both art and history. These knots often result because the aims of history and the aims of art are not aligned, often pulling in entirely different directions. History wants facts; art wants meaning. History strives to validate sources; art strives to evoke emotion. History is more substance; art is more style. History begs accuracy; art begs aesthetics. The two disciples often love yet hate one another as they strive to serve their different masters. This discord has never been more apparent to me than in my recent experience of painting the feature image of the translation of the Book of Mormon, By the Gift and Power of God, and illustrating the subsequent chapters for the book From Darkness unto Light. Using images of the translation of the Book of Mormon as the primary example, this article attempts to briefly illuminate why this discord between art and history exists and the roles that art and scholarly sources play in our understanding of historical events. Based on these ideas, this article concludes with three practical implications for gospel teachers and learners about the use of gospel art in teaching and learning religious doctrine and history.

The Language of Art

Often an inherent misunderstanding exists between artists and historians partly because the two disciplines speak different native languages. The language of history is facts and sources, and the language of art is symbolic representations in line, value, color, texture, form, space, shape, and so forth. The tension lies in that historians, scholars, and teachers often want paintings that are historically accurate because images often shape our perceptions of history as much as, or perhaps more than, many of the scholarly works about history. A great example of how works of art shape our historical memory would be to ask, “How did George Washington cross the Delaware?” What comes to mind? Probably Emanuel Leutze’s famous Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), with Washington standing heroically toward the front of a rowboat in daylight. However, historically the boat is probably wrong, the weather is off, the flag is anachronistic, and the pose is just downright unrealistic (try standing that way in a rowboat and it will probably capsize). Thus, when paintings carry apparent egregious historical errors, manipulations, or complete fabrications, there are some who bristle and wonder why the artist didn’t paint it more accurately, wishing that painters and sculptors and the like wouldn’t engage in revisionist history by distorting reality.[4]

However, artists often have little to no intent of communicating historical factuality when they produce a work. Artists want to communicate an idea, and they want to use whatever medium or principle and element of art it takes to communicate that idea to their viewers. In doing research on this topic, I interviewed a handful of well-known and talented Latter-day Saint artists and asked them various questions regarding the responsibility of an artist to paint historical reality. Almost unanimously, they said the artist carries no responsibility to do so. When I asked this question of prominent LDS artist Walter Rane, who has painted many Church history–related paintings, he said:

I don’t think an artist has any responsibility to be historically accurate. If I am doing a painting I can do whatever I want. I can look at a sunset and paint it blue instead of red if I want to express something. I don’t feel like as an artist I have a responsibility to be historically accurate unless someone has commissioned me [to do so]. Art is self-expression. Art is communication. That’s what art is. If I’m trying to express something that is important to me I’ll do whatever I want. If it means putting Christ in contemporary clothing, or whatever, if it’s important to the message I’m trying to make then I’ll do it.[5]

Thus, for example, one of the greatest biblical painters and illustrators of all time, Rembrandt, set many of his biblical paintings in quaint seventeenth-century Dutch settings and dress perhaps because it communicated biblical ideas in ways familiar to his audience but far from historical reality. I was once conversing with a group of Muslim religious educators from Saudi Arabia when they visited a local LDS seminary. One of them pointed to perhaps our most oft-printed LDS image—Del Parson’s portrait of Christ in a red robe titled The Lord Jesus Christ—and he asked me who that person in the portrait was. “Jesus,” I told them. They all broke out in spontaneous laughter. “You think that is what Jesus looks like? An American mountain man?” they said humorously. “What do you think he looks like?” I asked in return. “Us!” they said in unison. And perhaps they are right. But whether Jesus looks American or Swedish or Saudi Arabian or African American, all that matters to an artist is the message that comes through to the audience receiving that image.[6]

In an interview I conducted with Del Parson, painter of The Lord Jesus Christ, he had a similar attitude of feeling over facts:

When I’m painting the Savior I am going for emotion more than anything else. When they [the viewers] see the painting, they see the Savior. I did the best I could [to create the painting] with what I had. I got some material and wrapped it around a model and painted it. The last thing I was worried about was whether the robe was at the right level at the neck. The whole thing I was worried about was can they feel the Savior?[7]

Artist J. Kirk Richards, when speaking with me about painting the First Vision, said:

I’ve had people talk about what the “correct” clothing is [of the First Vision] and so on and so forth. In reality, I don’t care. I want it to feel [like] what we feel when we think about the First Vision. And a lot of times historical details detract from getting that feeling across. So, very low on my list of considerations is historical detail. Sorry historians. Don’t hate me. . . . I’m usually trying to present the principle of a spiritual truth rather than a historical truth.[8]

Thus, because art and artists’ first language is usually meaning and message, it is not necessary for an artist to be bilingual and able to fluently speak the language of history. Paradoxically, a piece of art can and often does communicate “truth” without being historically true, as countless images over the years have exemplified.[9] Duke professor of religion and art David Morgan says that the meaning of “truth” in art is therefore “ambivalent . . . whose meanings range from ‘credible’ to ‘accurate,’ and ‘correct’ to ‘faithful’ and ‘loyal.’ In each case, true designates not the image as much as the proactive contribution of the ‘eye of faith.’”[10]

However, while art and artists are often credited with making historical, and particularly religious, ideas come alive and plainer to understand,[11] an inherent problem enters when the language of religious art becomes translated into the language of history by its viewer. What we see becomes what we believe, and often, therefore, what we think we know about facts and details of history. And when we learn religious facts and history (from scholars or historians) that contradict what we think we know (through artistic renderings), a state of cognitive dissonance—and in the case of religious art, spiritual dissonance—can often be the result. The translation of the Book of Mormon is perhaps the most pertinent and pressing example of this problem today in the LDS mind.

Artistic Renderings of the Book of Mormon Translation

In the fall semester of 2013 in one of my Doctrine and Covenants courses at Brigham Young University, we were studying about the translation of the Book of Mormon (D&C sections 6–9). I showed and discussed with my class many of the sources[12] about Joseph translating the Book of Mormon using the seer stone(s) placed in a hat, presumably to eliminate light. We had a great discussion and learning experience together. Later that day I received the following email from a student:

I just wanted to thank you for today’s lesson about Joseph Smith and the translation process. A little over a year ago, I started spending a lot of time with my friend [name omitted] who had recently left the Church and was pretty much convinced of atheism. He had researched some things about Joseph Smith and would tell me all about it. . . .When he would tell me about these things, my first instinct was to deny it and say, “No that can’t be true; that’s not what the illustrations of the translation look like and I’ve never been taught that at church.”. . .

This time in my life turned out to be a huge trial of my faith.[13]

Of particular importance to this article is the phrase “That can’t be true; that’s not what the illustrations of the translation look like.” This student (and many others) had formed historical knowledge of the translation through representations in religious art. Many of us do the same. Regarding the translation of the Book of Mormon, this becomes particularly problematic because none of the currently used Church images of the translation of the Book of Mormon are consistent with the historical record.

Over the past year with my research assistant, Jordan Hadley, I have documented and analyzed all of the paintings of the translation of the Book of Mormon that have ever been published in the Church’s Ensign magazine since its inception in 1971 through March of 2014. This provided us with the last forty-three years of published representations of the translation of the Book of Mormon in one of the Church’s official magazines. In all, there have been fifty-five times the Ensign has depicted the translation of the Book of Mormon over the past forty-three years, repeatedly using seventeen different images. The most oft-used image is Del Parson’s Joseph Smith Translating the Book of Mormon (also printed in the Gospel Art Kit and Preach My Gospel), used a total of fourteen times since January of 1997.[14] All of the Ensign images are inconsistent with aspects of documented Church history of the translation process of the Book of Mormon. For example, in each of the seventeen Ensign images, Joseph Smith is shown looking into open plates (not closed or wrapped or absent plates). In eleven of the images Joseph Smith has his finger on the open plates, usually in a studious pose, as though he is translating individual characters through intellectual interpretive effort and not through revelatory means through the Urim and Thummim. Only one painting[15] in the past forty-three years depicts Joseph Smith using Urim and Thummim; this image was used only twice (once in November of 1988 and once in February of 1989). Most tellingly, none of the images ever printed in the history of the Ensign (or recent Church videos, such as Joseph Smith, Prophet of the Restoration) depict the translation process of the Book of Mormon as having taken place by placing a seer stone or the Nephite interpreters in a hat. Is there any wonder, then, that there is confusion in the minds and hearts of believing persons when they learn through repeated scholarly sources that the Book of Mormon was apparently translated through seer stones placed in a hat to obscure light and that the plates were often concealed under a cloth or not in the room,[16] and not by opening the plates with his finger on them and studying it out?

Unpainted Translation Images

A logical question emerges upon analyzing the published images of the translation: Why don’t the renderings of the translation reflect the seer-stone(s)-in-a-hat process if that is how it happened based upon multiple historical sources? I cannot answer that question, as only those who have commissioned, created, and published the past artistic images can give an informed response. The language of art is a factor, however. When I asked Walter Rane about creating an image of the translation with Joseph looking into a hat, he surprised me by telling me that the Church had actually talked to him a few times in the past about producing an image like that but that the projects fell by the wayside as other matters became more pressing. Note how Walter refers to the language of art as to why he never created the image:

At least twice I have been approached by the Church to do that scene [Joseph translating using the hat]. I get into it. When I do the drawings I think, “This is going to look really strange to people.” Culturally from our vantage point 200 years later it just looks odd. It probably won’t communicate what the Church wants to communicate. Instead of a person being inspired to translate ancient records it will just be, “What’s going on there?” It will divert people’s attention. In both of those cases I remember being interested and intrigued when the commission was changed (often they [The Church] will just throw out ideas that disappear, not deliberately), but I thought just maybe I should still do it. But some things just don’t work visually. It’s true of a lot of stories in the scriptures. That’s why we see some of the same things being done over and over and not others; some just don’t work visually.[17]

In my interview with J. Kirk Richards, when I asked him how he would approach the translation of the Book of Mormon image, he said to me, “It would be hard for me to paint a painting with Joseph with his head in a hat. We would have no sense of the vision of what is happening inside.”[18] Thus great and gifted artists like Walter Rane and J. Kirk Richards and others, who do know the history and have considered creating translation paintings with Joseph using the hat, have not created an image to reflect that history because it doesn’t translate well in the language of art. Their point of view, as artists, is perfectly valid: If the image doesn’t communicate the proper message, even if it is historically accurate, then the art won’t be effective and has failed to speak properly in its native tongue.

As an artist, I can sympathize with Walter and Kirk. Many of my own sketches of the translation for the book project From Darkness to Light didn’t look right or feel right in terms of the marvelous work and wonder of the Book of Mormon. I joked that some of my sketches with Joseph in the hat should have been called “The Sick of Joseph” because he looks like he is vomiting into the hat. Upon seeing these sketches, multiple people, unfamiliar with our history, asked me if this was the case. The images didn’t communicate anything about inspiration, visions, revelations, miracles, translation, or the like. Just stomach sickness. For past artists (or Ensign art directors) who may have known about the historical documents of the translation, it may simply be that choosing to depict Joseph with his finger in open plates with a pensive look was more visually appealing and communicative than the historical reality of what the translation may have looked like. It is easy for critics to assume a coordinate cover-up or historical rewrite when looking at the images,[19] but perhaps the unjuicy reality may have more to do with a preference for speaking artistic language that is more “true” in its communication, even if the depicted events contain historical error.

However, when my colleagues Michael MacKay and Gerrit Dirkmaat introduced me to their manuscript, notwithstanding the tension between the language of art and the language of history (and in spite of my artistic shortcomings when compared to more qualified artists), I felt impressed that it was time to try and provide a faithful, well-executed artistic image (as many of the existing images of using the hat to translate are either deliberately pejorative or devoid of much artistic merit) of the translation of the Book of Mormon that better reflected historical reality.

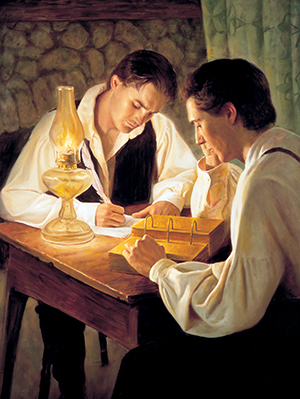

The Painting By the Gift and Power of God

Toeing a difficult line, my image of the translation attempts to be based upon factual reality while also employing the principles and elements that create good art. I wanted the image to be edifying for a believer and sufficiently accurate for a scholar. In terms of historical accuracy, the image is set from actual interior photographs taken in the replica Whitmer home on location in Fayette, New York, where Joseph and Oliver finished the translation of the Book of Mormon. There is not a sheet between them, and the plates lie wrapped in a linen cloth, as Emma Smith explained they often lay. Both Joseph and Oliver were young at this time (twenty-three and twenty-two years old, respectively, in June of 1829), and I wanted their youth reflected accurately in the image. The clothing is time-period specific; however, I didn’t research it in too much detail. (I am sure there is a clothing expert somewhere saying, “They didn’t wear that type or color of two-toned vests!”) The chair Joseph is sitting on is out of my front room. I did look at photos of top hats from the time period, and I painted the top hat white to try to be accurate to Martin Harris’s description of the “old white hat”[20] Joseph used, but it may not be exactly right (perhaps the brim is too wide or the bottom too deep; I don’t know). The model for Oliver Cowdery was a BYU student who providentially passed by as I was shooting photographs and just “looked” to me like Oliver Cowdery (similar hairline and facial features to some of the historical Oliver Cowdery photos), but not exactly. I modeled Joseph’s body after my own (naturally, some inconsistencies there). Joseph’s face was an amalgamation of profiles from the death mask and some of the features off the actor of the movie Plates of Gold, who has a great, youthful “Joseph” look to him. But, really, what did Joseph look like when he was twenty-three? Aside from stylized Sutcliffe Maudsley drawings done later in Joseph’s life, his historical image is difficult to pin down.[21]

Joseph translating with Martin Harris as his scribe.

Joseph translating with Martin Harris as his scribe.

Although my attempt tried to include basic historical accuracy, most notably Joseph’s face is not “buried” in the hat, as some translation sources claimed. Why? This is the question of my image I get most often from people who are familiar with the historical explanations of the translation. There are three reasons I chose not to bury his face in the hat: (1) Simply put, it didn’t work visually for this composition. I wanted an unfamiliar viewer to immediately recognize it was Joseph Smith, and having his face in the hat was difficult for many of the people whom I ran preliminary sketches by. Without knowing the historical background, they didn’t know who or what this image depicted. (2) Returning to the language of art, I wanted to communicate the message of inspiration in this image. The human face carries a lot of subtle emotion, and by covering Joseph’s face in the hat, it was difficult to portray ideas such as prayer, pondering, focus, reverence, and revelation. A hat obscured all of those ideas visually. By showing his face I could more easily portray inspiration elements in Joseph—the studying it out in his mind and heart and the revelatory gift of a seer—yet still have the image be set in historical reality (as opposed to a figurative or abstracted composition). (3) Last, his face outside the hat still reflects historical reality. Logically, Joseph had to put his face into, and pull his face out of, the hat. I imagine the moment depicted in my painting as Joseph getting ready to go into the hat to see—starting the process of revelation. He almost looks like he is getting ready to tip forward, and the anticipation of that moment causes the viewer want to put Joseph’s face into the hat, visually measuring Joseph’s face and looking into the opening of the brim, fitting the two together. With this composition your mind can imagine what Joseph is about to do—the revelatory mode he is moving into—and the gift he is starting to exercise at this moment. Having the face out of the hat helped to provide a more interactive and purposeful viewing experience.

Speaking of viewing experience, any well-composed piece of art uses artistic devices to move the eye of the viewer in certain orders, directions, and places. I tried to do the same in this image. When you initially look at the image, odds are that you will look first at the hat. I placed it centrally in the painting for that reason and used the brightest white to pull the eye there. I wanted the viewer to look at the hat first, to deal with it, think about it, examine it, and process it. Next, the eye moves up to Joseph’s face, seeing him move into a revelatory mode and connecting it with the opening in the hat. The viewer then might naturally move to the covered plates on the table, contrary to past visual representations of open plates and sheets. Next, the eye moves to Oliver Cowdery in the background as he sits and scribes “the sound of a voice dictated by the inspiration of heaven” (Joseph Smith—History 1:71 footnote). Deliberately, the diagonal line of the floor and wall joint coming in from the bottom left of the image, and the vertical line made by where the walls meet, visually pass through Joseph and Oliver and lead the eye to the hat and the plates. Finally, after the viewer examines the hat, Joseph, the plates, and Oliver, I hope his or her eye expands outward into the simplicity of the space. Using artistic devices of light, I intentionally included the window with sun streaming through, illuminating the ground and room to suggest ideas such as light, truth, revelation, and inspiration upon Joseph.

While my painting is a faithful attempt to visually depict the translation of the Book of Mormon in a manner that is more consistent with the historical records than previous translation paintings, it contains some elements that are purely aesthetic and speak the language of art. Although I tried to accommodate both, the inherent tension between artistic merit and historical reality tugged at me during the creation of this painting. A commentary on one detail in the painting, the lit lantern, is a fitting item and topic upon which to illustrate this tension between the language of art and the language of history. After examining the central aspects of the painting such as the white hat, Joseph, the plates, and Oliver, ultimately I hope the viewer’s eye looks up and sees the black lantern above Joseph and Oliver. Michael MacKay, coauthor of From Darkness to Light (for which this image was created), asked me, when he saw the painting in process, why the lantern was lit in the middle of the bright daylight sun in the room. Historical reality? No. Artistic device? Yes. And without explaining, you can already deduce what that illuminated lantern might suggest and symbolize. That’s the joy of the language of art, even when it isn’t entirely historically accurate.

Implications for Gospel Teachers and Learners

With this background explaining why artistic expressions do not always conform to doctrinal or historical factuality (nor do they need to), there are some logical implications for how one might approach the use of art in gospel teaching and learning. I suggest the following three implications: (1) Teach students to see art symbolically and religiously, not just historically and factually; (2) recognize that students may form religious doctrine and history from artistic images, and thus conscientiously help them incorporate interpretive images to better fit into a proper framework of belief; and (3) understand that images depicted in official Church publications are not official declarations of doctrine or history.

Implication #1: Teach students to see art symbolically and religiously, not just historically and factually.

When using art and images in gospel teaching, help students approach art in the native language of art. The following two common pedagogical approaches are diametrically opposed examples. In one classroom, Harry Andersen’s classic The Second Coming image is projected on the LCD screen and the teacher asks the following: “Take a look at the following painting about the Second Coming. What is wrong with it? How should it have been painted?” The students quickly respond, “He’s wearing a white robe and the scriptures say that Christ will be wearing red when he returns.” While this may be a good attention-getter activity, this teacher oriented the students to a factual, doctrinal, accuracy-centered perspective, perhaps unconsciously implying to learners that art should be consistent with historical facts or doctrinal truths and that if it isn’t, the image may be faulty or inferior. An approach such as this may not only cause students to miss the power and message of the image, but it may also unconsciously orient them to see artistic images as a fact-based medium, causing religious ideas and truths to be potentially confused in the process.

In another classroom, a teacher puts up a painting of Carl Bloch’s masterpiece The Resurrection of Christ, which depicts Christ bursting from the tomb in glory, and asks, “What symbolism or metaphors do you see depicted in this painting on the Resurrection?” The students look intently at the image in a completely different, abstract way. “The lilies coming out of the tomb could represent rebirth or resurrection,” one student offers. Another says, “His hands being raised up could show his reverence or gratitude to God the Father.” The second teacher positioned the students to view art through a symbolic, metaphorical, representative lens, suggesting that art does not have to be factually or scripturally precise (lilies don’t grow in sealed tombs, and there is no record of Jesus’ immediate actions when he came forth) to convey meaning, message, and truth. Using art in its native, interpretive tongue helps learners more accurately explicate messages that may get lost in translation if they try to interpret an image strictly through the vocabulary of factuality.

Implication #2: Recognize that students may form religious doctrine and history from artistic images, and thus conscientiously help them incorporate interpretive images to better fit into a proper framework of belief.

Great paintings have the potent force to profoundly shape ideas and beliefs regarding students’ understanding of doctrine and history. As a gospel teacher I have said to classes, “I want each of you to close your eyes and picture King Noah and Abinadi.” The students momentarily do so, and then I ask, “How many of you pictured King Noah as an overweight man sitting on a throne?” Nearly all hands go up. “How many of you pictured Abinadi with his shirt off, as an older man who is apparently in extremely good shape?” Same majority. “What kind of pet does King Noah have?” “Leopards!” the students shout. “How many?” “Two!” The students give these factual details confidently and quickly. The only problem is that these are not factual details. At least not scripturally factual details, as the Book of Mormon never mentions Abindadi’s age, Noah’s weight, nor his pet leopards. What the students were describing were the details of Arnold Friberg’s classic painting Abinadi Before King Noah, an image with such influence and widespread distribution that it has shaped these artistic interpretations into almost certain facts for an entire generation of Church members.

Thus, because art carries such power to form ideas, religious educators would do well when using artistic images to preface them with comments such as, “Here is one interpretation of this event.” Walter Rane told me that, simply, “we need more [varied] images out there” so that nobody confuses one of them as the “official” way things looked or happened, but can appropriately be seen simply as one person’s expression.[22] Perhaps this is one reason why the Church has recently produced three varied depictions of the sacred temple video. Although “the script in each of the films is the same,” each varies the setting and unspoken details differently, which may imply to viewers that each film is an interpretation and not a singular historical declaration.[23] When I asked J. Kirk Richards the question “From an artist’s perspective, what would you want religious educators and students of religious education to bear in mind when using art to teach and learn the gospel?” he answered, “Always preface that this is an artist’s interpretation of it, and the reason why I [as an educator] am using it is because. . . . If you feel like you have historical facts that contradict the imagery you can say that: ‘We know this or research shows this’—I don’t think an artist would mind that at all. I certainly would not mind if someone said that [about my images].”[24]

The more we recognize that our students often form scriptural, doctrinal, and historical ideas from the imagery we use, the more responsible and conscientious we become in how we may help students understand, use, and incorporate interpretive images to better fit into a proper framework of belief.

Implication #3: Understand that images depicted in official Church publications are not official declarations of doctrine or history.

Just because a piece of art is published in the Ensign, it does not necessarily depict the Church’s official position on a scriptural, doctrinal, or historical theme. While Church magazines do what they can to attempt to have images be doctrinally and historically accurate, the reality is that it is not always feasible nor reasonable to do so. In an email communication, a representative at Church magazines wrote to me, “While our library consists of many images created from the past, we do not always have the time, money, or resources to create new art and direct every minutia of detail [of images] for monthly publications.”[25] Thus the Church often publishes paintings created in the past from artists (both LDS and of other faiths) who may have depicted a scene with some doctrinal or historical inconsistencies. To innocently expect all images in Church publications to be doctrinally and historically accurate creates problems and confusion both for the viewer and the Church—such as when Church magazines photoshopped one of Carl Bloch’s Resurrection images in the December 2011 Ensign (digitally removing the wings from the angels and capping their clothing to cover their exposed shoulders) to perhaps try and better match LDS doctrines and standards.[26] Understanding the language of art removes unnecessary assumptions for both the consumer and producer of art in a Church venue.

Additionally, sometimes the temporal realities of deadlines, resources, time, and money influence why doctrinally or historically inaccurate images may be created or used in official Church outlets. Del Parson said that while understandably “the Church has got to be very careful when they throw an image out there,” some of his paintings were done quickly. “You get a call and they [the Church magazine] need it today,” Del told me, “and so I did the best I could with what I had”[27]—suggesting that temporal realties sometimes influence how much he can put into creating an image with scriptural, doctrinal, or historical accuracy. Walter Rane said, “If they want it to be historically accurate I’ll do my best. There have been times with Church history paintings when I was commissioned to do something . . . and I tell them up front I’m not a researcher. I’m not a scholar (at all). Therefore I ask them to supply me with information that would help.”[28] Sometimes that is possible, and for some images it simply isn’t. Understanding that each image produced by the Church has artistic and temporal factors that sometimes influence the images they use and produce should influence how we, as teachers and learners, should see and use those images. We would do well to remember that official doctrine is proclaimed by prophets, not by painters or printers.

Conclusion

A few years ago Walter Rane did a large multi-image series of Book of Mormon themes. He told me, “When I was first commissioned to do that series on the Book of Mormon I had shied away from doing it because we don’t know what the people and setting looked like.” Gratefully, he still painted these masterful images and printed them in a beautiful book.[29] Since then, these fresh Book of Mormon images have been displayed and used and printed often in Church venues to bless and inspire many persons in many places. However, when consulting with a well-known Book of Mormon scholar in the beginning stages as the images were being sketched out for production, the scholar said to him, “You shouldn’t even do this project. We should stop doing Book of Mormon paintings until the archaeologists have better determined what things really looked like.” Walter Rane said, “So I went ahead and ignored that advice and did the images anyway . . . as best as I could.”[30] To think that we cannot produce or use a painting unless it is factually, doctrinally, or historically accurate is detrimental to the pursuit and expression of truth. Such a historical, wrong-unless-its-factually-accurate perspective would undermine much of the great art and its potent effects the world over.

Using Doctrine and Covenants 50:19–21 as a guide, as teachers and students of the gospel we must recognize that there is both “the word of truth” and “the spirit of truth.” That duality is true not only in preaching, but also in painting. A painting can be devoid of accurate words or facts or history (words of truth) yet still inspire, edify, uplift, and be of God (the spirit of truth). History needs art, and art needs history, but each speaks its own native tongue that is most conducive to its desired outcomes—which, for artists, is primarily to create meaning and message, evoking emotion and inspiration. As Del Parson said to me as we concluded our interview, “We are just trying to make something tangible that is intangible. It’s our way of worship.”[31] As we let painters speak the language of art, and understand why they do so even if it isn’t doctrinally or historically accurate, we can be better prepared to responsibly use their images of truth as we help others teach and learn the gospel.

Notes

[1] John Ruskin, Modern Painters, vol. 3 (London: 1898), 61.

[2] Anthony Sweat received a bachelor of fine arts degree in painting and drawing from the University of Utah in 1999.

[3] Jacque Louis David’s The Death of Marat (1793) is a prime example of a historical painting that is not entirely historically accurate. The painting depicts the death of the radical French Revolution journalist Jean-Paul Marat as he was murdered in his bathtub by a French loyalist. However, it is full of historical inconsistencies, artistic license, and idealizations intended to cause the viewer to sympathize for the martyr and the revolution. The painting was meant as a political piece of art, not a historical recreation of the actual murder scene.

[4] See Corey Kilgannon, “Crossing the Delaware, More Accurately,” in the New York Times (December 23, 2011), for an article describing a recent, more historically accurate painting done to try and correct the historical inconsistencies in Leutze’s famous painting.

[5] Walter Rane, interview by author, February 7, 2014.

[6] A great example of the “feeling” of a Christ-centered painting being more important than the historical reality of it comes from popular LDS artist James Christensen. He tells of an experience when he sat down with LDS Church President Spencer W. Kimball about a painting of Jesus he was working on and asked President Kimball, “If you were going to hang a painting of the Savior in your office, what would you want that picture to look like?” Christensen relates that the prophet “took off his glasses and put his face about a foot away from mine and said, ‘I love people; that’s my gift. I truly love people. Can you see anything in my eyes that tells you that I love people? In that picture, I would like to see in the Savior’s eyes that he truly loves people.’” See James C. Christensen, “That’s Not My Jesus: An Artist’s Personal Perspective on Images of Christ,” BYU Studies 39, no. 3 (Fall 2000): 11–12.

[7] Del Parson, interview by author, February 7, 2014.

[8] J. Kirk Richards, interview by author, January 24, 2014.

[9] One such image, for example, is John Trumbull’s 1817 classic Declaration of Independence, showing forty-two of the fifty-six signers of the declaration in one room together, although the declaration was signed by different men over multiple days. They were never all together in the same room at the same time signing the document, as the image shows, a fact that caused John Adams to detest the painting. While historically inaccurate, it is an example of a painting being “true” (to an idea), even though it distorts historical truth.

[10] David Morgan, The Sacred Gaze: Religious Visual Culture in Theory and Practice (Oakland CA: University of California Press, 2005), 77.

[11] Artist and historian Graham Howes summarized this point by stating, “As early as 1005 a local synod at Arras [France] had already proclaimed that ‘art teaches the unsettled what they cannot learn from books.’ Two centuries later we find Bonaventure defining the visual . . . as an open scripture made visible through painting, for those who were uneducated and could not read.” See Graham Howes, The Art of the Sacred (New York: I. B. Tauris, 2007), 12.

[12] See Michael Hubbard MacKay, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds., Documents, Volume 1: July 1828–June 1831, vol. 1 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, Richard Lyman Bushman, and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2013), xxxi–xxxv. See also Michael Hubbard MacKay and Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, From Darkness unto Light: Joseph Smith’s Translation and Publication of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015); and “Book of Mormon Translation” at https://

[13] Private e-mail message to author, September 18, 2013.

[14] Ensign, January 1997, 38; August 1997, 11; July 1999, 41; January 2001, 22; February 2001, 47; December 2001, 29; February 2002, 15; October 2004, 55; February 2005, 12; January 2006, 37; October 2006, 40; January 2008, 37; October 2011, 19; December 2012, 9.

[15] Gary E. Smith, Translation of the Book of Mormon. Interestingly, Gary E. Smith painted a very similar image of the translation of the Book of Mormon that was published in the Ensign in December of 1983 on the inside front cover. In that image, Joseph Smith does not have the breastplate or the Urim and Thummim. Gary Smith seemingly redid the painting essentially using the same composition for his November 1988 painting, but in that painting, Joseph Smith is wearing the breastplate and seems to be holding a pair of spectacles, or what could be the Urim and Thummim, in his right hand. See Ensign, November 1988, 46.

[16] According to Emma Smith, the plates “often lay on the table without any attempt at concealment, wrapped in a small linen table cloth.” “Last Testimony of Sister Emma,” Saints’ Herald, October 1, 1879, 289–90.

[17] Rane, interview.

[18] Richards, interview.

[19] Two critics wrote, after viewing a historically inaccurate image of the translation of the Book of Mormon in the Ensign, “What could be the reason for leaving these items out of a publicity painting except to distance the translation from the ocultic practices that really characterized the Book of Mormon translation!” See Bill McKeever and Eric Johnson, “A Seer Stone and a Hat—‘Translating’ the Book of Mormon,” Mormonism Research Ministry, retrieved from http://

[20] The “white hat” comes from Martin Harris’s telling of an interesting story where Joseph used his seer stone to find a lost pin he had dropped into some straw. He said Joseph took the seer stone “and placed it in his hat—the old white hat—and placed his face in his hat. I watched him closely to see that he did not look one side; he reached out his hand beyond me on the right, and moved a little stick, and there I saw the pin, which he picked up and gave to me. I know he did not look out of the hat until after he had picked up the pin.” Joel Tiffany, “Mormonism,” Tiffany’s Monthly, August 1859, 164.

[21] See Ephraim Hatch, Joseph Smith Portraits: A Search for the Prophet’s Likeness (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1998), 31–45.

[22] Rane, interview.

[23] See Tad Walch, “LDS Church begins using a third new temple film,” Deseret News, July 15, 2014.

[24] Richards interview.

[25] Private e-mail message to author, February 10, 2014; grammar standardized for publication.

[26] See Ensign, December 2011, 54, for the edited Carl Bloch image. See “On Immodest Angels . . . ,” May 16, 2012, http://

[27] Parson, personal interview with the author, February 7, 2014.

[28] Walter Rane, personal interview with the author, February 7, 2014.

[29] Walter Rane, By the Hand of Mormon: Scenes from the Land of Promise (Deseret Book: Salt Lake City), 2003.

[30] Walter Rane, personal interview with the author, February 7, 2014.

[31] Del Parson, personal interview with the author, February 7, 2014.