The Allegory of the Olive Tree: An Instructional Model for Leaders

José A. Bamio

José A. Bamio, "The Allegory of the Olive Tree: An Instructional Model for Leaders," Religious Educator 16, no. 3 (2015): 142–57.

José A. Bamio (jabamio@gmail.com) was an independent researcher in Vigo, Spain when this article was published.

"Thus saith the Lord, I will liken thee, O house of Israel, like unto a tame olive tree, which a man took and nourished in his vineyard" (Jacob 5:3)

"Thus saith the Lord, I will liken thee, O house of Israel, like unto a tame olive tree, which a man took and nourished in his vineyard" (Jacob 5:3)

The prophet Jacob, one of the early writers in the Book of Mormon, quotes an extensive allegory known as the allegory of the olive tree,[1] which was originally penned by Zenos, an ancient Hebrew prophet. By doing so he purports to answer the question “How is it possible that [the Jews], after having rejected the sure foundation [Christ], can ever build upon it, that it may become the head of their corner?” (Jacob 4:17). He begins with a brief introduction of the main characters: “Thus saith the Lord, I will liken thee, O house of Israel, like unto a tame olive tree, which a man took and nourished in his vineyard” (Jacob 5:3). Throughout seventy-seven verses he tells the story of a Lord’s efforts to care for and tend a vineyard that includes an original and various tame olive trees, as well as various wild olive trees. After concluding his narrative, Jacob affirms that it is an allegorical description of the dealings of God with the house of Israel and the fulfilling of his covenants in the latter days (see Jacob 6).

Many studies have been conducted suggesting the meaning of the symbols, characters, and actions of the allegory as representing a literal history of the house of Israel, drawing parallels with historical events and gospel dispensations. These studies focus on the relationship between the tree (as a representation of communal Israel) and the Lord of the vineyard. Conversely, Dan Belnap explores the relationship between the Lord and his servant in the vineyard, elaborating on the concept that in Isaiah, as well as in other scriptures, “the term ‘Israel’ is used to denote two identities—the individual servant and the collective social group.”[2] In his approach, Belnap “presents the servant as a covenant member of Israel who has responsibilities for the eventual salvation of communal Israel and the greater world.”[3] His approach “allows for the actions of the servant, as a growing, maturing individual, to be just as important in the plan as the trees are.”[4] He shows that the servant’s growth is the result of his working under his master’s directions, following a carefully designed training that gradually leads him to acquire the very traits of his master. Belnap concludes, “The true power of the allegory comes from understanding that He [God] is seeking not only for oneness and good fruit [in the vineyard] but also for servants who become companions, associates, and equals”[5] with him.

By considering the servant as representing the individual nature of Israel, this paper follows partially the approach of Dan Belnap, but it focuses rather on the work system exhibited by the Lord of the vineyard and his servant as they tend the vineyard, showing that they follow a recurrent model in their labors. This pattern seems to be an instructional model for leaders worthy to be examined and tested.

Further, by considering the tree as representing the communal nature of Israel, this paper will suggest that the tree represents two facets of communal Israel, which, if understood, would allow for a better appreciation of the labor performed for the benefit of the trees.

The Natural Olive as a Dual Representation

From the outset of the allegory, the Lord defines what the tree represents: “I will liken thee, O house of Israel, like unto a tame olive tree, which a man took and nourished in his vineyard” (Jacob 5:3). The verb “took” indicates that the tree was chosen; the same concept appears in Isaiah 5:2, where the Lord plants the “choicest vine.” There are also wild olives in the story, representing peoples whose fruits are of inferior quality but, once inserted through grafting into the mainstream of the tame olive tree, they improve and match the desired fruit quality.[6]

In many other scriptural references, Israel is compared to plants in a cultivated garden.[7] The common concepts that stand out in these analogies are “election,” followed by “cultivation,” all this denoting an endearing relationship and a purpose. But nowhere is this analogy so elaborate as in the allegory. And certainly it is not an easy task to depict metaphorically the relationship of God with the house of Israel, with the people “the Lord hath chosen . . . to be a peculiar people unto himself, above all the nations that are upon the earth” (Deuteronomy 14:2). The paramount importance of olive trees for ancient cultures in the Mediterranean basin[8] makes them a suitable representation of a people defined as “a peculiar treasure” (Exodus 19:5). So the very initial sentence of the allegory provides not only the context of the story but the emotional and spiritual framework of a “peculiar” relationship.

But the house of Israel is more than a collectivity, just as a tame olive tree is much more than an uncultivated or wild one. In describing this institution to the early Saints, Peter said that they, “as lively stones, are built up a spiritual house, an holy priesthood, . . . a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation, a peculiar people, . . . which in time past were not a people, but are now the people of God” (1 Peter 2:5, 9, 10). I suggest that in order to represent this complex and purposeful society, its power and workings, the allegory also distinguishes between the branches and the roots of the natural olive tree. The branches represent groups of persons, again differentiating between “natural” and “wild” branches. Some branches are plucked off and transplanted into other grounds, where they keep growing and bring forth fruits. Other branches are grafted into the tree, and some others are plucked off and burned. The branches interact with the roots in a relationship of mutual reinforcement, but sometimes they interact in frank opposition. The Lord of the vineyard endeavors to keep a balance between both entities, striving to retain the roots.

I suggest that we are here dealing with a dual representation. The tree represents the house of Israel in its two facets: on the one hand, the tree depicts the members of the house of Israel (or Church), and as such, it is a representation of individuals, families, and human groups; and on the other hand, the tree is a representation of the Church, as an institution of divine origin, with a structure and priesthood channels. The branches are more suited to represent individuals and families which are able to bring forth fruits (natural or wild ones), while the roots are a good representation of the Church as a divinely approved organization that extracts the nutrients of the gospel out of the soils for the blessing of the families.

The Nourishment from the Roots

Jacob himself mentions in his brief final commentaries, “For behold, after ye have been nourished by the good word of God all the day long, will ye bring forth evil fruit, that ye must be hewn down and cast into the fire? Behold, will ye reject these words? Will ye reject the words of the prophets; and will ye reject all the words which have been spoken concerning Christ” (Jacob 6:7–8). This statement makes clear that the word of God, which zeros in on the doctrine of Christ’s Atonement, is the vital nutrient in the ascending sap from the roots that reaches and nourishes the branches.[9] Representations of other components of this sap are not identified in the allegory.[10] On the other hand, in the allegory the gardeners recognize the force and influence that the branches have on the roots (see Jacob 5:18, 34, 48).

This interpretation of the branches, the roots, and the nourishment from the roots in the allegory allows for an appropriate representation of the relationship between the three main entities in the plan of salvation: the families, the Church, and the Savior.[11]

The Labor in the Vineyard

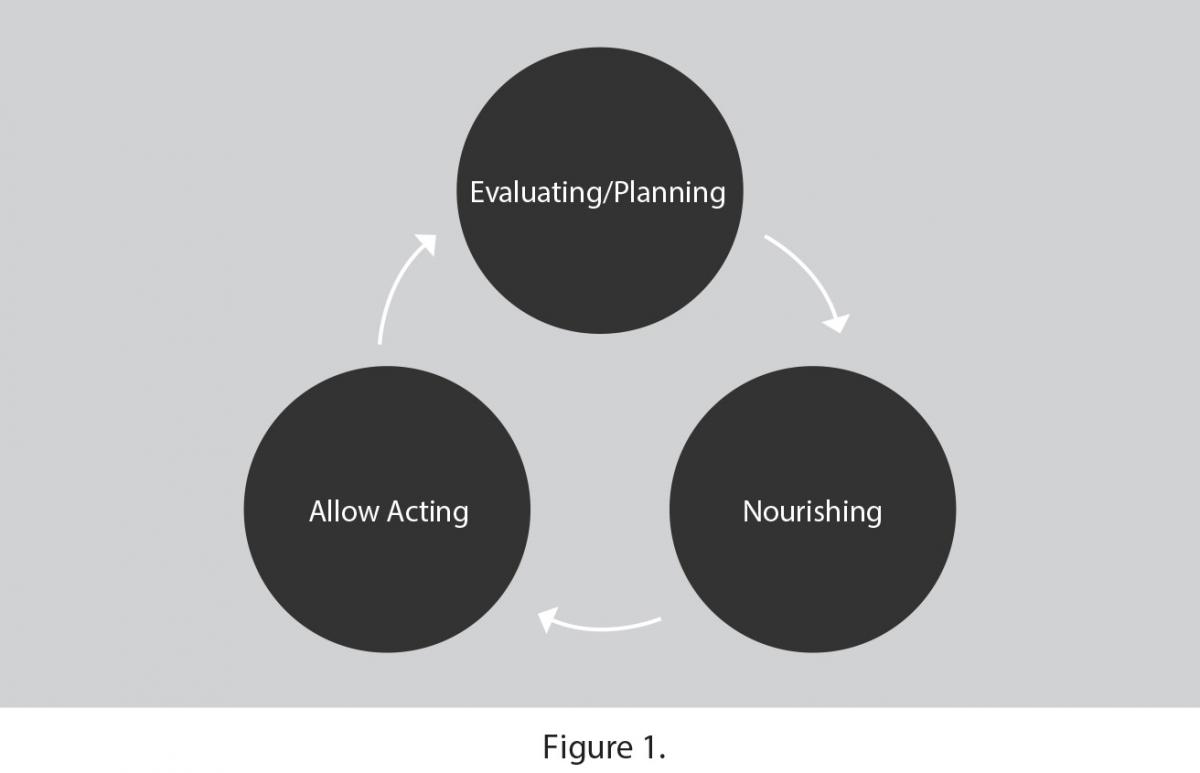

The labor of the gardeners follows a cyclical pattern, each cycle consisting of three stages. The first stage is an assessment and planning session, in which the Lord of the vineyard and the servant evaluate the trees, the fruits, and the general conditions in the vineyard. They discuss the possible causes of the present outcomes and devise an action plan. Next, they perform the horticultural tasks according to their plans, which I summarize under the title “Nourishing,” and then they depart to allow for the trees to act. After a certain time, the cycle starts all over again.

Let’s take a closer look at these three stages:

I. Evaluating/

The first undertaking of both gardeners is to assess the condition of the trees and the quality of their fruits. Diagnosis necessarily must precede prescription. Words or phrases such as “saw,” “said,” “taste of the fruit,” “watch the tree,” “look here,” “beheld it was good,” “according to my words,” “what shall we do unto the tree?,” and “what could I have done?” allow us to recognize this phase of assessment, reasoning, and planning.

Each cycle begins with such a session in which the Lord and servant perform most or all of the following activities:

- They observe the general condition of the tree/

trees, branches, and fruits. - They try to understand the reasons for such results; they reason, “Behold, the branches of the wild tree have taken hold of the moisture of the root thereof, that the root thereof hath brought forth much strength” (Jacob 5:18).

- They assess the effects of their former labors for the trees: “if we had not grafted in these branches, the tree thereof would have perished” (v. 18).

- They devise new plans leading to the desired fruits: “Let us prune it, and dig about it, and nourish it a little longer, that perhaps it may bring forth good fruit” (v. 27).

- They repeat this procedure for each tree in the vineyard in each zone where they have planted trees.

These sessions also exhibit several traits that are worth mentioning:

- These sessions seem to be used by the Lord of the vineyard to communicate instructions to the servant. But there is also an open and respectful two-way communication between both individuals, with questions and answers from both parties, with speaking and listening, proposals and counterproposals, assignments and reports. Final decision making rests on the Lord of the vineyard, as could be expected.

- As Dan Belnap has shown, the information handled in the sessions grows in complexity in the course of time, evidencing an increase in the capacity of the servant to understand the processes and to understand that he is getting more reliable. The scope of the tasks also increases from working solely on the mother tree to all the trees in the vineyard.

- The agents conducting the assessment observe conditions, question results, and reason about the causes. But there are feelings and emotions all the way too: “It grieveth me that I should lose the trees” (v. 51), says the Lord of the vineyard to the servant. He speaks of joy, “that I may rejoice exceedingly” (v. 60), and promises, “ye shall have joy with me” (v. 75). At a very frustrating time in the vineyard, there is even mourning: “And it came to pass that the Lord of the vineyard wept” (v. 41). This shows that they are not merely concerned about production or numbers, but they are concerned about the trees as living entities continuously immersed in a life-and-death struggle. They want to obtain good fruits but are also concerned about preserving the roots and the branches (v. 60).

II. Nourishing (cultivating or nurturing)

Under this title are grouped all of the horticultural tasks that are carried out by the agents in the allegory to the benefit of the trees in the vineyard. These labors make the difference between a wild and a cultivated olive tree. The cultivated olive trees bring forth bigger and high quality fruits. In order to achieve such outcomes, the gardeners do the following tasks:

- Pruning: cutting or removing dead or excessive foliage. One purpose is to keep the tree’s top equal to its roots; i.e., to keep a balance between them.

- Digging: loosing the soil to make nutrients and moisture available to the roots.

- Nourishing: adding fertilizers to the ground.

- Grafting: propagating by inserting branches into a growing tree.

- Transplanting: transferring branches to be replanted somewhere else.

- Burning: destroying old and removed branches.

- Clearing the ground: removing infected materials and debris from the ground, usually by fire.

- Dunging: fertilizing with organic materials.[12]

We can arrange these tasks in two groups according to their effects on the trees: the tasks aimed to foster their growth and the ones that seek to remove obstacles that hinder or delay progress. In this context, the tasks that provide the tree with nutrition or add something to improve its quality (nourishing, dunging, grafting) constitute a driving force, while the tasks that reduce or remove what blocks the trees from nourishing or growing well (digging, pruning, uprooting, transplanting, burning, clearing out obstructions) are unblocking forces working to reduce the effect of restrictive forces in the system. The Lord of the vineyard is aware of the need of both kinds of efforts.

He is also aware of the existence of a circuit within the tree, whereby nutrients flow from the roots up to the branches and back from the leaves to the roots. “And he said unto the servant: Behold, the branches of the wild tree have taken hold of the moisture of the root thereof, that the root thereof hath brought forth much strength; and because of the much strength of the root thereof the wild branches have brought forth tame fruit” (v. 18). And at a time of general corruption in the vineyard, the servant tries to find an explanation: “Is it not the loftiness of thy vineyard—have not the branches thereof overcome the roots which are good? And because the branches have overcome the roots thereof, behold they grew faster than the strength of the roots, taking strength unto themselves. Behold, I say, is not this the cause that the trees of thy vineyard have become corrupted?” (v. 48). The Lord of the vineyard responds by instructing the servant to dig, prune, and dung once more and to reinsert branches into their original trees, and then pluck or “clear away the branches which bring forth bitter fruit, according to the strength of the good and the size thereof; and ye shall not clear away,” he continues, “the bad thereof all at once, lest the roots thereof should be too strong for the graft, and the graft thereof shall perish” (v. 64–65). Wilford Hess provides a botanical explanation for this: “There is a distinction between mineral uptake by roots, particularly the influence of nitrogen compounds, which are necessary for wood growth, and carbon assimilation by photosynthesis, which takes place in the leaves and supplies carbon for the forming of the plant body, including the fruit. In order to get a full crop of olives an equilibrium must be maintained between these two processes.”[13]

In summary, an important criterion the Lord of the vineyard uses to determine the due proportion of driving/

III. Allow acting:

The branches represent individuals and families which are able to bring forth fruit.

The branches represent individuals and families which are able to bring forth fruit.

Once the gardeners have labored in the vineyard according to their plan, they leave and allow the trees to act. Attention is called to the fact that the outcomes of their work are not guaranteed, as attested by the italicized words in these verses: “I will prune it, and dig about it, and nourish it, that perhaps it may shoot forth young and tender branches, and it perish not” (v. 4). “And this will I do that the tree may not perish, that, perhaps, I may preserve unto myself the roots thereof for mine own purpose” (v. 53), “that, perhaps, the trees of my vineyard may bring forth again good fruit; and that I may have joy again in the fruit of my vineyard, and, perhaps, that I may rejoice exceedingly that I have preserved the roots and the branches of the first fruit” (v. 60; emphasis added; see also vv. 11, 27, 54). The gardener’s actions in favor of the tree do not warrant the fruits but create an environment where the trees may develop to their fullest potential.

The allegory right from the beginning sets the scenery where the olive trees perform their acting: “a tame olive tree, which a man took and nourished in his vineyard; and it grew, and waxed old, and began to decay” (v. 3). Throughout the allegory, the nature of the vineyard works constantly as a restricting force against the development of the trees and the improvement of the fruits. Zenos’s, Jacob’s, and latter-day audiences would readily recognize that these restricting forces are related to the aftermaths of the Fall of Adam, at least in its physical aspects. But a representation of the spiritual consequences of the Fall are also presented in the allegory as restricting forces, and Jacob himself and the text of the allegory make clear that each one of these restricting forces has its counterpart or propelling force:

The restricting force of the physical Fall

The allegory shows a vineyard that needs constant care and work in order to counteract its natural tendency to decay and decompose. Hugh Nibley said, “That is the second law of nature, but according to Jacob, it is the first to which nature is subjected—the inexorable and irreversible trend toward corruption and disintegration; it can’t be reversed. It rises no more, crumbles, rots, and remains that way endlessly, for an endless duration.”[14] This is also known as the entropy principle, which describes that everything tends, if no new energy is added, to assume a lesser degree of organization and an inferior quality of energy, till it becomes useless. For an olive tree to become domesticated, it must receive a good amount of energy and care during a long time; left alone, it will lose its higher properties and degenerate and very likely die.[15] The gardeners work to reverse this degrading process. They toil in an apparently hopeless cause, but at several periods they overcome opposition and achieve the desired fruits. Their actions are based on the knowledge of propelling forces in the system that operate in the opposite direction of the restricting forces.

The driving force

In other writings in the Book of Mormon, Jacob refers to the terrible fate of the earth and its inhabitants after the Fall: “There must needs be a power of resurrection, and the resurrection must needs come unto man by reason of the fall; . . . wherefore, it must needs be an infinite atonement—save it should be an infinite atonement this corruption could not put on incorruption. Wherefore, the first judgment which came upon man must needs have remained to an endless duration. And if so, this flesh must have laid down to rot and to crumble to its mother earth, to rise no more” (2 Nephi 9:6–7). In his final comments on the allegory, he identifies again the Atonement as the driving force that counteracts entropy. He asks his audience the following questions: “Yea, today, if ye will hear his voice, harden not your hearts; for why will ye die? For behold, after ye have been nourished by the good word of God all the day long, will ye bring forth evil fruit, that ye must be hewn down and cast into the fire? Behold, will ye reject these words . . . and deny the good word of Christ, and the power of God, and the gift of the Holy Ghost, and quench the Holy Spirit, and make a mock of the great plan of redemption, which hath been laid for you?” (Jacob 6:6–8).

The restricting force of the spiritual Fall, or the misuse of agency

In the interaction of the roots of the tame tree with the wild branches, there is a risk that the branches overcome the roots, resulting in an impoverishing rather than an enriching transaction. Instead of improving, the fruits as well as the entire tree lose quality. The servant tries to find an explanation for this failure, asking, “Is it not the loftiness of thy vineyard—have not the branches thereof overcome the roots which are good? And because the branches have overcome the roots thereof, behold they grew faster than the strength of the roots, taking strength unto themselves” (Jacob 5:48). If we consider the roots as symbolizing the Church and the branches as representing the human groups being gathered into it, this impoverishing transaction resulting in the loss of quality in the fruits and the tree is a suitable representation of the Church’s condition during apostasy.[16]

The driving force

In between the trend of nature to become corrupted and the action of the infinite Atonement, which causes corruption to put on incorruption, we have a third factor or force: the moral agency of man to accept the redemptive work performed on his behalf. This important force is of spiritual (not physical) nature and can act as a restricting or a driving force. A proper use of moral agency means alignment and submission to the Atonement, which is represented in the allegory by an adequate interchange of nourishment between the leaves and the roots, while a misuse of agency is described as “loftiness” of the vineyard, where wild branches consciously conflict with the natural roots (which would represent the corpus of the living witnesses, according to this article). Gradually and to the extent of the leaves’ capacity to support the roots, the branches yielding the bitter fruit will be plucked off from the tree.

The allegory seems to depict that it takes the two driving forces combined together to bring forth the miracle of the natural fruit—that is, the Atonement of Christ and the moral agency of man. The importance of the latter is shown in the allegory through the extensive periods of time the gardeners concede the trees to act for themselves. The all-encompassing nature of the effort needed to combine both forces can be appreciated in the stirring concluding plea of Jacob to his people: “I beseech of you in words of soberness that ye would repent, and come with full purpose of heart, and cleave unto God as he cleaveth unto you” (Jacob 6:5).

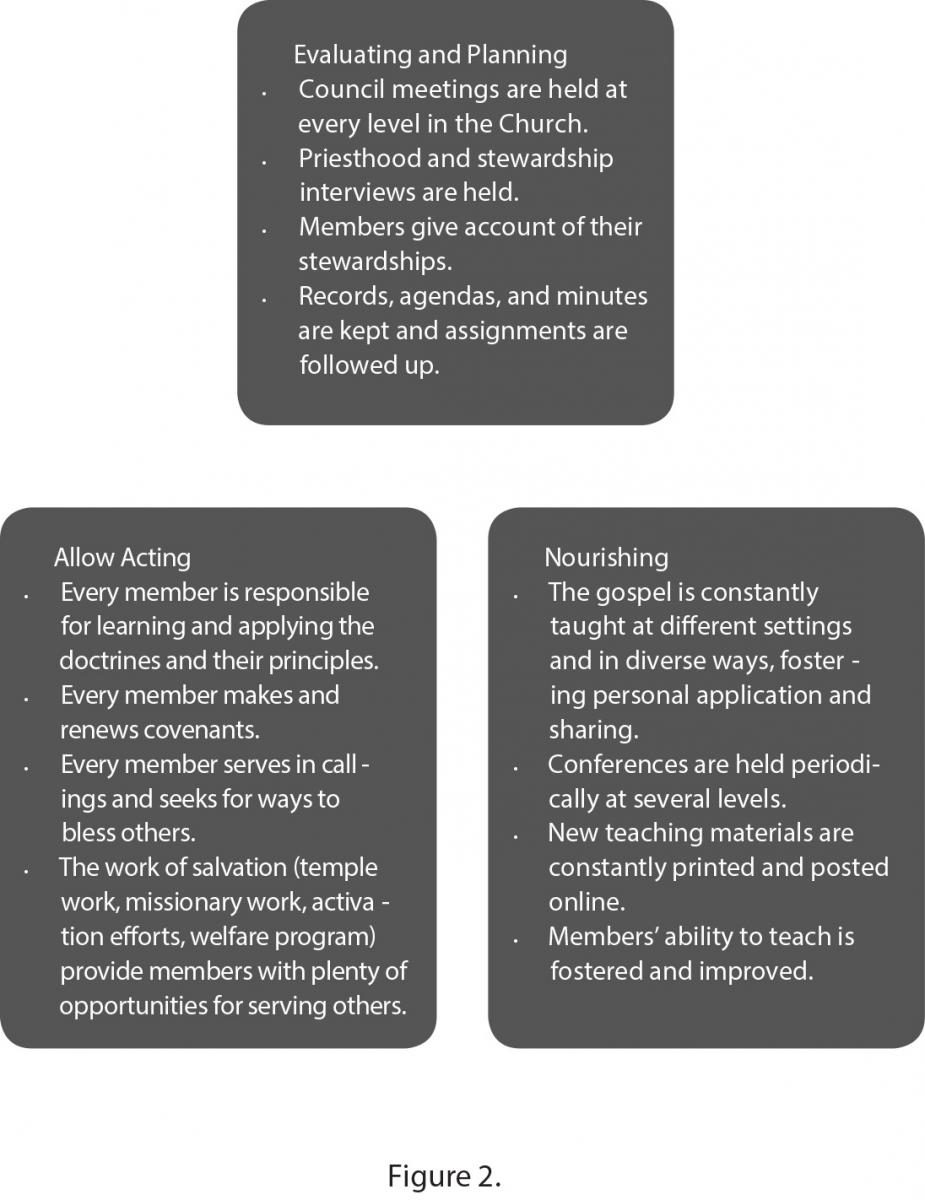

The Leadership Pattern of the Allegory in Current Church Practices

Scott H. Faulring pointed out how the Book of Mormon instructed Joseph Smith in the task of restoring and organizing the Church in this dispensation.[17] In this regard, it would not be an overstatement to highlight the contribution of the allegory in terms of exposing key leadership principles and processes that have been hallmarks of the restored Church. Richard Lyman Bushman has shown that the form of government in the Church restored by Joseph Smith differed from the other religious institutions of Joseph’s time.[18] Very early there occurred in the Church a transferring of power from the prophet to councils at every level, where members would assess their needs, reason and plan together, give reports, and seek revelation—all functioning under the direction of priesthood keys with sufficient autonomy.[19]

In the following chart are shown some parallels between the leadership process exhibited in the allegory and the traits of government and functioning established in the LDS Church, most of them since its very first days:

Conclusion

Commenting about the allegory, Jacob bears testimony “that the things which this prophet Zenos spake, concerning the house of Israel, in the which he likened them unto a tame olive tree, must surely come to pass” (Jacob 6:1). Besides dealing with prophecy, this allegory delivers much more than prophetical and historical information about the dealings of God with the house of Israel and the world. The fact that the Lord prepared a way for us to receive Zenos’s allegory in this dispensation, a jewel that has been lost to the world for centuries, places upon us the burden of studying and learning from it as much as we can. This article identifies some useful lessons on leadership by pointing out a pattern followed by the Lord of the vineyard and his servants in their labors: (1) assessing and counseling about a plan, (2) performing diverse tasks that aim to nourish the trees or to release them from the things that impede nourishment and growth, and (3) granting a period of time for the trees to respond to their labors, after which the process starts over again. The chief aim of the labor is to bring the branches into contact with the life-giving sap of Christ’s Atonement and to create the necessary conditions for growth, synergy, and oneness in the garden. This pattern is a valuable teaching model for leadership, and I have briefly outlined some ways that the restored Church has adopted this model and has been applying it since the early days of the Restoration.

In addition, the interpretation suggested here of the branches representing the families and human groups that belong to the Church, and the roots standing for the Church as divine institution, allows us to understand the emphasis given in the allegory to the internal interactions within the trees. The actors involved in the drama of the allegory would now be four instead of three: the Lord of the vineyard, the servant, the branches, and the roots, where the servant could be but an individual manifestation of the branches and the narrative of his performance a perusing of some of the workings that are expected from the branches.

Under this premise, the roots represent the need for a figure (the Church) in receiving and distributing the proper nourishment to the individual members and interacting with them in a life-giving circuit, where branches and roots are supposed to support each other. We are informed from the very start that the original tree had been chosen and tamed (see v. 3), which may be a way of representing its qualification or divine provenance. Throughout the text, the Lord of the vineyard expresses his desire for high-quality fruits, but he is also committed to preserving the roots. This suggests at least two things: First, the indispensability of a “living” connection between the soils and the branches through a good root structure. No branch can survive feeding from dead roots. Second, the roots are to preserve their domesticated traits in order to serve as worthy conduits of the “living water” that will bring forth quality fruits out of even wild branches. Translated, each dispensation requires living and authorized oracles, living true prophets and witnesses, to carry the nutrients of the gospel to the families. No wonder Jacob extols God in his final comments of the allegory: “And how merciful is our God unto us, for he remembereth the house of Israel, both roots and branches” (Jacob 6:4).

Finally, the allegory locates the house of Israel in a setting that represents the “garden” that came after the Fall, a garden of the second state, in contrast to the paradisiacal garden of the Creation. The allegory introduces the forces that are present in this environment: the restrictive forces that are consequences of the Fall and subdue everything. According to Jacob, the branches can counteract these forces and yield high-quality fruit only through accepting the good word of the Atonement of Christ that ascends from the roots—the living witnesses—and by aligning and interacting positively with the roots in a circuit ever improving, that now tends to oneness, to Zion.

Notes

[1] For the sake of brevity, hereafter referred to as the allegory.

[2] Dan Belnap, “‘Ye Shall Have Joy with Me’: The Olive Tree, the Lord, and His Servants,” Religious Educator 7, no. 1 (2006): 37.

[3] Dan Belnap, “‘Ye Shall Have Joy with Me,’” 38.

[4] Dan Belnap, “‘Ye Shall Have Joy with Me,’” 37.

[5] Dan Belnap, “‘Ye Shall Have Joy with Me,’” 48.

[6] Paul, in an allusion to an apparently known notion of olive trees representing people, wrote, “For I speak to you Gentiles, inasmuch as I am the apostle of the Gentiles. . . . And if some of the branches be broken off, and thou, being a wild olive tree, wert grafted in among them, and with them partakest of the root and fatness of the olive tree” (Romans 11:13, 17).

[7] David Rolph Seely provided this insight: “Also prominent is the comparison of Israel as a plant and the Lord as the gardener: ‘Thou shalt bring them in, and plant them in the mountain of thine inheritance’ (Exodus 15:17); ‘As the trees of lign aloes which the Lord hath planted, and as cedar trees beside the waters’ (Numbers 24:6); ‘Moreover I will appoint a place for my people Israel, and will plant them’ (2 Samuel 7:10); ‘For the vineyard of the Lord of hosts is the house of Israel, and the men of Judah his pleasant plant’ (Isaiah 5:7); ‘The Lord called thy name, A green olive tree, fair, and of goodly fruit’ (Jeremiah 11:16); ‘And I will plant them in this land assuredly with my whole heart and with my whole soul’ (Jeremiah 23:41). This agricultural metaphor emphasizes the dependence of Israel on her God, the care which he gives to his plants, and the expectation of productivity measured by the quality and quantity of the fruit at the harvest. Clearly the closest parallel to Zenos’s allegory is found in Isaiah’s song of the vineyard (Isaiah 5:1–7) where Israel is compared with an unproductive vineyard that the Lord attempts to make fruitful but finally allows to be destroyed by its enemies and lack of rain.” David Rolph Seely, “The Allegory of the Olive Tree and the Use of Related Figurative Language in the Ancient Near East and the Old Testament,” in The Allegory of the Olive Tree, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and John W. Welch (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994), 299.

[8] For a detailed explanation of the importance of the olive culture, see John Gee and Daniel Peterson, “Graft and Corruption: On Olives and Olive Culture in the Pre-Modern Mediterranean,” in The Allegory of the Olive Tree, 186–25.

[9] Boyd K. Packer highlights the life-sustaining property of the Atonement while making another analogy with roots and branches in a comment as afterthought of his own parable “The Mediator”: “Through Him [Christ] mercy can be fully extended to each of us without offending the eternal law of justice. This truth is the very root of Christian doctrine. You may know much about the gospel as it branches out from there, but if you only know the branches and those branches do not touch that root, if they have been cut free from that truth, there will be no life nor substance nor redemption in them.” Boyd K. Packer, in Conference Report, April 1977, 80.

[10] Dallin H. Oaks, for instance, explains that the Church provides the families, among other things, with the doctrines, ordinances, and priesthood keys. See Dallin H. Oaks, “Priesthood Authority in the Family and the Church,” in Conference Report, October 2005, 25–26.

[11] “We begin by affirming three fundamental doctrinal principles. First, both the Church and the eternal family are presided over by priesthood authority. The government and the procedures of the Church and the family are different, but the foundation of authority—the priesthood—is the same. Second, the Church organization and the family organization support one another. Each is independent in its own sphere, but each has the same mission—to help accomplish God’s purpose to bring to pass the eternal life of His children (see Moses 1:39). Third, the Latter-day Saint family and the Church both draw their nourishment and their direction from our Lord Jesus Christ.” Dallin H. Oaks, “The Priesthood and the Auxiliaries,” Worldwide Leadership Training Meeting, January 2004, 18.

[12] Following is a list of the verses where these labors are mentioned: pruning (vv. 4, 5, 11, 27, 47, 62, 64–66, 69, 76); pruning in order to keep the top and the root equal (vv. 37, 48, 65, 66); digging (vv. 4, 5, 11, 27, 47, 63, 64); nourishing (vv. 3–5, 11, 12, 20, 22–25, 27, 28, 31, 34, 47, 58, 63, 71, 75, 76); grafting (v. 8, 9, 10, 17, 18, 30, 34, 52, 54–57, 60, 63–65, 67, 68); transplanting (vv. 21, 23–25, 43, 44, 52, 54); burning (vv. 7, 9, 26, 37, 42, 45–47, 49, 58, 66, 77); clearing the ground (vv. 44); dunging (vv. 47, 64, 76).

[13] Wilford M. Hess, Daniel Fairbanks, John W. Welch, and Jonathan K. Driggs, “Botanical Aspects of Olive Culture Relevant to Jacob 5,” in The Allegory of the Olive Tree, 524.

[14] Hugh W. Nibley, “The Meaning of the Temple,” in Temple and Cosmos, vol.12 of Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, 10.

[15] “If both ‘tame’ and ‘wild’ trees receive the same cultural attention by growers, the ‘tame’ or domesticated tree will, almost without exception, yield fruit of superior quality and size. On the other hand, if the same trees, both ‘tame’ and ‘wild,’ are left without attention, the ‘wild’ is more likely to survive, even though the fruit will be genetically inferior.” Wilford M. Hess, Daniel Fairbanks, John W. Welch, and Jonathan K. Driggs, “Botanical Aspects of Olive Culture Relevant to Jacob 5,” in The Allegory of the Olive Tree, 510–11.

[16] If we compare this allegorical depiction with scriptural real descriptions of apostasy periods, we can see interesting parallels: “And it was because of the pride of their hearts, because of their exceeding riches, yea, it was because of their oppression to the poor, withholding their food from the hungry, . . . making a mock of that which was sacred, denying the spirit of prophecy and of revelation, murdering, plundering, lying, stealing, committing adultery, rising up in great contentions, . . . and because of this their great wickedness, and their boastings in their own strength, they were left in their own strength; . . . and they saw that they had become weak, like unto their brethren, the Lamanites, and that the Spirit of the Lord did no more preserve them” (Helaman 4:12, 13, 24).

[17] Scott H. Faulring, “The Book of Mormon: A Blueprint for Organizing the Church,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 7, no. 1 (1998): 60–69.

[18] Richard Lyman Bushman, “The Theology of Councils”, in Faith and Reason: Essays in Honor of Truman G. Madsen (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002), 434–38.

[19] “The concept of a council in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints embodies both a philosophy of administrative behavior and an organizational body or unit. . . . Church councils coordinate and schedule activities, gather information, plan future programs or events, and make decisions and resolve problems for their units. . . .

“The philosophy of a council is what sociologist Thomas O’Dea called a ‘democracy of participation’ in Mormon culture,” (The Mormons (Chicago, 1964), 165. At periodic council meetings both individual and organizational needs are considered. Recognizing the unique circumstances surrounding a particular unit, geographical area, or set of individuals, the council identifies the programs and activities that need to be planned and correlated. (The council does not have final decision-making power, this resides with the unit leader, such as the stake president or bishop.)

“Councils are more than operational coordinating mechanisms. They also serve as vehicles for family, ward, stake, region, area, or general Church teaching and development. As members participate in councils, they learn about larger organizational issues. They see leadership in action, learning how to plan, analyze problems, make decisions, and coordinate across sub unit boundaries. Participation in councils helps prepare members for future leadership responsibilities.” “Priesthood Councils,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 2007), 3:1141–42.