“They Pursue Me without Cause”: Joseph Smith in Hiding and D&C 127, 128

Andrew H. Hedges

Andrew H. Hedges, “They Pursue Me without Cause”: Joseph Smith in Hiding and D&C 127, 128,” Religious Educator 16, no. 1 (2015): 43–59.

Andrew H. Hedges (andrew_hedges@byu.edu) is a coeditor of The Joseph Smith Papers and was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this article was written

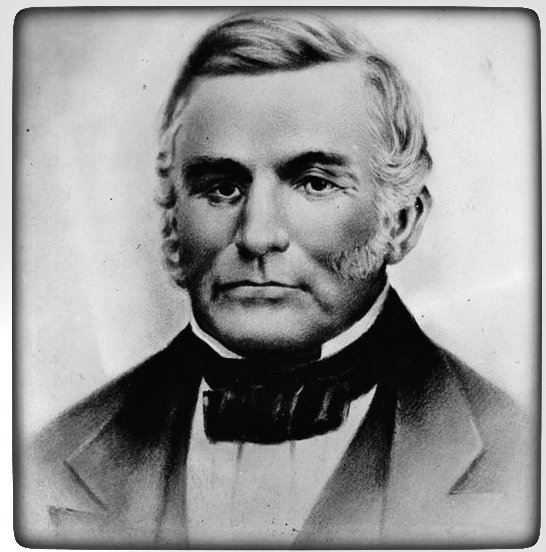

The Prophet's troubles began on the evening of May 6, 1842, when someone shot former Missouri governor Lilburn W. Boggs in his home in Independence, Missouri. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The Prophet's troubles began on the evening of May 6, 1842, when someone shot former Missouri governor Lilburn W. Boggs in his home in Independence, Missouri. Courtesy of Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

On September 1, 1842, three days after emerging from three weeks of hiding to avoid arrest for allegedly plotting to assassinate former Missouri governor Lilburn W. Boggs, Joseph Smith wrote a letter “to all the saints in Nauvoo” explaining the need for them to keep more complete records of their baptisms for the dead.[1] Not surprisingly, Joseph also took the opportunity to comment briefly on his flight from legal authorities. “They pursue me without cause,” he wrote in the first sentence of his letter, “and have not the least shadow, or coloring of justice, or right on their side, in the getting up of their prosecutions against me; . . . their pretensions are all founded in falsehood of the blackest die.” Joseph then told those with whom he was doing business that he had left his affairs in capable hands, and assured his supporters that he would return when “the storm was fully blown over.”[2]

Two days later Joseph was back on the run, having barely escaped arrest while having lunch on September 3.[3] Four days after that, on September 7, Joseph—still in hiding—dictated a second, longer letter to the church giving additional instructions on baptisms for the dead. Unlike his first letter, Joseph said nothing about his situation in this second letter, which concluded with a lengthy, celebratory review of the rise and progress of the Church and an enthusiastic call for action on the part of its members.[4]

With the exception of a few lines, then, Joseph chose to say very little about his personal circumstance in these two letters—now canonized as Doctrine and Covenants 127 and 128, respectively—with the result that the tone of each is overwhelmingly positive and optimistic. From other sources, however, it is clear that he was downplaying a very dangerous situation, and one that weighed heavily on his mind and the minds of his supporters. These sources also support his charge that the proceedings against him were unjustified, and demonstrate that it was the very illegality of these proceedings that ultimately led to a resolution of the crisis. And finally, these sources provide significant details about how these two letters were originally presented to the Church and then preserved—the point being that it is one thing to write or dictate a letter, but quite another to ensure that it is safely recorded for future reference. This article is an effort to tell this larger story of the difficult circumstances under which Joseph produced and preserved these two letters, and to help Church members appreciate how unfounded and illegal the charges against him were.

The Prophet’s troubles began on the evening of May 6, 1842, when someone shot former Missouri governor Lilburn W. Boggs in his home in Independence, Missouri. The same day, Joseph himself was some three hundred miles to the east in Nauvoo, Illinois, where he attended the officer drill of the Nauvoo Legion in the morning, visited an ailing Lyman Wight at some point, and possibly attended the Masonic lodge in Nauvoo in the evening.[5] Joseph spent the following day, beginning at 7 a.m., commanding the 2,000 troops of the Nauvoo Legion during its semiannual general parade before “a great concourse of spectators. & many distinguis[h]ed Strangers.”[6] In spite of Joseph’s well-documented presence in Nauvoo, however, enemies of the Church were linking the attack on Boggs to Joseph Smith and urging public officials to arrest him as early as May 14—the same day, incidentally, that news of the attack first reached Nauvoo.[7] The accusations hit print one week later when the editor of the Quincy Whig repeated a rumor that Joseph had prophesied a year earlier of Boggs’s death “by violent means.”[8] Understandably alarmed at such reports, Joseph wrote immediately to the Whig’s editor, denying any complicity in the affair and making the very reasonable suggestion that Boggs, as a politician, had probably been shot by a political enemy.[9]

Joseph’s protestations notwithstanding, others soon took up the cry. Chief among these was John C. Bennett, whose immoral conduct and incorrigible attitude had resulted in his excommunication at precisely the same time news of the attack on Boggs was working its way east to Nauvoo.[10] Evidently trying to save face after his fall from grace, Bennett wrote a series of letters to the editor of Springfield’s Sangamo Journal attacking Joseph Smith and the Church. In his first letter, dated June 27, 1842, Bennett merely repeated the charges that had been leveled against Joseph in Missouri in 1838.[11] But in his second and third letters, dated July 2 and 4, 1842, Bennett brought his attack up-to-date by providing a plausible explanation for how, precisely, Joseph was involved in the attempt on Boggs’s life: Joseph had prophesied in a public meeting in 1841 of Boggs’s imminent death, Bennett charged, after which he sent Orrin Porter Rockwell to fulfill the prediction.[12] Written from the perspective of a former insider on Nauvoo affairs and accompanied by several affidavits supporting his testimony, Bennett’s letters added an air of authority to what had earlier been vague rumor.

On July 20, 1842, less than one week after Bennett’s letters were published, Boggs—who recovered fully from his wounds—signed two affidavits before justice of the peace Samuel Weston regarding the attempt on his life. Boggs told Weston that “he beleives and has good reason to beleive from Evidence and information now [in] his possession that Joseph Smith . . . was Accessary before the fact of the intended Murder,” with Orrin Porter Rockwell serving as the trigger man. Boggs also reported that “the said Joseph Smith is a Citizen or resident of the State of Illinois” and asked the governor of Missouri to “make a Demand” on the governor of Illinois “to Deliver the said Joseph Smith . . . to some person Autherised to receive and Convey him” to Jackson County, Missouri, “there to be dealt with according to Law.”[13]

In legal terms, Boggs was asking that Joseph Smith be extradited to Missouri to stand trial. According to the US Constitution, however, one can be extradited only if he is charged with committing a crime in one state and then fleeing to another.[14] Boggs’s affidavit made no such charge; it simply accused Joseph, a resident of Illinois, of somehow being “accessary” to the crime before it was committed but made no reference to his being in Missouri to commit the crime or fleeing to Illinois afterward. Without such a charge, there was no legal basis for initiating extradition proceedings—a technical deficiency which Boggs, a former governor, should have been aware of. Whether he was ignorant on this point or simply chose to disregard it is unclear.

The same ambiguity exists regarding the understanding and motives of the then-current governor of Missouri, Thomas Reynolds, to whom Boggs was directing his plea. On July 22, 1842, two days after Boggs signed his affidavit, Reynolds filled out a printed requisition form and sent it to Illinois governor Thomas Carlin for the “surrender and delivery” of Joseph Smith to the state of Missouri. After referencing a supporting document (in this case, Boggs’s affidavit), the printed form noted that the person charged with the crime was a “fugitive from justice” who had “fled to” another state—even though, as we have seen, the supporting document made no such claim in this particular case.[15] Whether Reynolds was aware of the transformation or not, his use of the printed form essentially rewrote Boggs’s affidavit to fit the constitutional requirements for extradition, and at the same time helped to hide its glaring deficiency under a layer of legal documentation.

The final step in the process presented no surprises. On August 2, 1842, having learned from “the Executive authority of the State of Missouri” that Joseph “fled from the justice of said State and taken refuge in the State of Illinois,” Illinois governor Thomas Carlin issued a warrant for Joseph’s arrest. Like Reynolds before him, Carlin was given Boggs’s affidavit but either missed or ignored its deficiency—a lapse that becomes positively ironic when he states that his actions were “pursuant to the Constitution and Laws of the United States.” Carlin addressed his warrant to Thomas King, undersheriff of Adams County, Illinois, and directed him to deliver Joseph into the custody of Edward Ford, agent for the state of Missouri. Carlin issued a similar writ for Rockwell’s arrest, based on a similar requisition from Reynolds.[16]

Six days later, on August 8, 1842, King and two other men—probably Ford and James Pitman, a constable from Adams County—arrested Joseph and Rockwell for their alleged roles in the attempted assassination.[17] Both men immediately applied to the Nauvoo Municipal Court for writs of habeas corpus. Demonstrating his knowledge of extradition law, Joseph justified his application on the grounds that he could show the court “the insufficiency of the writ and the groundlessness of the charge” against him. “I shall be able to prove before your honors that I was not out of the State of Illinois nor in the State of Missouri for the last two years,” he wrote, “and that I was not accesory to said assault, . . . not knowing anything about the intended assault nor anything concerning it until I was informed of it some time after it had occured.”[18] Granting Joseph and Rockwell their petitions, the court issued two writs of habeas corpus directing King to bring both men before the court “without excuse or delay” for an examination into the charges against them.[19]

The writs of habeas corpus saved Joseph and Rockwell from extradition but not in the way the municipal court intended. After being served with the writ, William Clayton recorded in Joseph’s journal, King “hesitated complying . . . for some time on the ground (as he said) of not knowing wether this city had authority to issue such writ.” After lengthy consultation, King and his companions decided to leave Joseph and Rockwell in the custody of Nauvoo city marshal Henry G. Sherwood “and returned to Quincy to ascertain from the governor,” Clayton continued, “wether our charter gave the city jurisdiction over the case.”[20] King took the warrants for Joseph’s and Rockwell’s arrest with him to Quincy, however, having either forgotten or never known that Sherwood could retain the prisoners only if he had the arrest warrants in his possession. No one present felt obligated to remind King of that specific requirement, with the result that Joseph and Rockwell were free the moment the lawman left Nauvoo.[21]

King returned two days later, evidently with instructions to comply with Reynolds’s requisition and see that Joseph and Rockwell were conveyed to Missouri.[22] Both men had gone into hiding during his absence, however—Rockwell ultimately traveling as far as Pennsylvania and New Jersey to avoid arrest, Joseph remaining closer to home.[23] King spent several days in the area looking for them, at the same time threatening to burn Nauvoo to the ground if Joseph and Rockwell could not be found.[24]

Joseph spent his first few days in hiding at the home of his uncle John Smith in Zarahemla, across the Mississippi River from Nauvoo in Iowa Territory. From there he moved to the home of Edward Sayers on the Illinois side of the river north of Nauvoo. After six days at Sayers’s home, he moved to Carlos Granger’s home in the northeast part of Nauvoo, where he stayed for two days before making his way to his red brick store. Four days later, having received a note from Emma indicating that she could care for him better at home than anywhere else, Joseph went home, although he waited until after dark to do so. Not until another six days had passed did he feel secure enough to make a public appearance.[25]

With King and other lawmen lurking about, keeping Joseph both safe and informed during this three-week period of hiding was no small task for his friends and supporters. Every precaution was taken to ensure that someone visiting Joseph did not accidentally betray his whereabouts to authorities from Illinois or Missouri. As he moved from John Smith’s home in Iowa to Sayers’s home in Illinois, for example, Joseph met with Emma and a few trusted friends on an island in the Mississippi River after dark on the night of August 11.[26] The following day, William Walker, with Joseph’s favorite riding horse in tow, crossed the river to Iowa “in sight of a number of persons . . . to draw the attention of the Sheriffs and public, away from all idea that Joseph was on the Nauvoo side of the river.” Only after that idea had been firmly planted in everyone’s mind did William Clayton and John D. Parker visit Joseph at his hideout north of Nauvoo, and even then they waited until after dark.[27] The ruse paid off, however, with “several small companies of men” searching for Joseph in Montrose, Nashville, Keokuk, and other places in Iowa Territory the following day. “They saw his horse go down the river yesterday,” Clayton recorded, “and was confident he was on that side.”[28]

Emma and others went to even greater lengths to throw pursuers off Joseph’s track on August 13 and 14 after her preparations to visit Joseph in a carriage attracted unwanted attention. Leaving the carriage at home, Emma walked downriver to Elizabeth Durphy’s house. After a short wait, William Clayton and Lorin Walker folded up the cover of the carriage in front of Joseph and Emma’s home to make it clear that Emma was not inside and started down the river. The two men quietly picked Emma up at Durphy’s, after which all three continued down the river—the opposite direction from where Joseph was hiding at Sayers’s north of Nauvoo—for another four miles. They then doubled back towards Nauvoo, skirted the city on its east side by two miles, and entered the trees closer to the river north of town. Even then, Parker dropped Emma and Clayton off a mile away from Sayers’s and returned home with the carriage, leaving Joseph’s visitors to cover the remaining distance on foot. Returning home the following day, Clayton and Emma—accompanied by Erastus Derby, who had been staying with Joseph—slogged along a muddy road to the river where they boarded a skiff and crossed over to the islands in the river before turning south. “Soon after we got on the water,” Clayton recorded, “the wind began to blow very hard and it was with much difficulty and apparent danger that we could proceed.” Finally reaching a point opposite Nauvoo, they rowed west between two islands and landed at Montrose, at which point Derby left to return to Joseph, and Clayton and Emma hitched a ride in another skiff crossing to Nauvoo.[29] Anyone who may have been watching Emma’s return in hopes of finding where Joseph was hiding would have thought he was on the Iowa side of the river.

Adding to the stress of the situation were the rumors that met Joseph’s supporters at every hand. On August 11, they heard that the sheriff of Lee County, Iowa Territory, might be joining the hunt.[30] Two days later, two reports arrived: first, Carlin had decided that extradition was illegal in this case, and that he “should not pursue the subject any further”; and second, Edward Ford, the agent from Missouri who was charged with conveying Joseph to Jackson County for trial, had returned home. Although both were favorable, Joseph’s friends didn’t accept either as legitimate. “All this it is thought is only a s[c]heme got up for the purpose of throwing us off our guard,” Clayton wrote, “that they may thereby come unexpected and kidnap Joseph and carry him to Missouri.”[31] By the morning of August 15, rumors were rampant that a militia unit was on its way to Nauvoo. Although these were readily dismissed as “a scheme to alarm the citizens,” another report received that evening from the Carthage postmaster seemed more legitimate. “[H]e had ascertained that the Sheriffs were determined to have Joseph,” Clayton recorded, “and if they could not succeed themselves they would bring a force sufficient to search every house in the City, and if they could not find him there they would search state &c.” Seven men were soon on their way by different routes to Sayers’s house to pass the word on to Joseph, who “prepared to leave the city, expecting he was no longer safe” when he first heard the news. As he learned more, however, Joseph decided against leaving Sayers’s at that point, and sought to calm the frazzled nerves of his friends. “He discovered a degree of excitement and agitation manifest in those who brought the report,” wrote William Clayton, who was present, “and he took occasion to gently reprove all present for letting report excite them, and advised them not to suffer themselves to be wrought upon by any report, but to maintain an even, undaunted mind.” The men calmed down after hearing Joseph’s words, but all concluded that Joseph should be prepared at a moment’s notice to leave for the Church’s lumbering operation in Wisconsin Territory if necessary.[32]

Joseph’s ability to soothe others during this difficult period belies the stress he himself was feeling, and the almost desperate measures he considered taking to avoid capture. Both are evident, however, in some of the letters he wrote to various associates while in hiding. After six days on the run, for example, Joseph sent some instructions to Wilson Law, major general of the Nauvoo Legion, outlining what Law should do if Joseph were caught. Noting that his orders were “the result of a long series of contemplation” and that he had concluded “never . . . to go into the hands of the Missourians alive,” Joseph instructed Law “forthwith, without delay, regardless of life or death to rescue me out of their hands” in the event of his capture. Joseph told Law that he would stay in hiding “for months and years” if necessary to avoid such a showdown and that he hoped his enemies would eventually “become ashamed and withdraw their pursuits” when they could not find him. “But if this policy cannot accomplish the desired object,” he reiterated, “let our charter, and our Municipality; free trade and Sailors rights be our motto, and go a-head David Crockett like, and lay down our lives like men, and defend ourselves to the best advantage we can to the very last.”[33]

In a letter to Emma the following day, Joseph admitted that the only thing that “kept [him] from melancholy and dumps” was the kindness and conversation of Erastus Derby, “which has called my mind from the more strong contemplations of things,” he wrote, “and subjects that would have preyed more earnestly upon my feelings.” He also wrote almost wistfully about going to Wisconsin, the idea having been suggested just the night before. “I must say,” he told Emma, “that I am pre-possessed somewhat, with the notion of going to the Pine Country. . . . I am tired of the mean, low, and unhallowed vulgarity, of some portions of the society in which we live; and I think if I could have a respite of about six months with my family, it would be a savor of life unto life, with my house.” Indicating that this was no mere pipe dream, he then outlined a plan by which he could, if necessary, meet Emma and their children north of Nauvoo at the house of John Taylor’s father, after which they would all “wend [their] way like larks up the Mississippi” to safety.[34]

As time progressed, it became clear that no such trip north would be necessary—at least not at the moment. The threat of capture had waned enough by August 23 that Joseph quietly returned home that evening, and by August 26 he was meeting with members of the Twelve and others about various issues. His first public appearance came three days after that, on August 29, when he appeared unexpectedly at a conference and addressed those present. Two days after that, on August 31, he addressed the Nauvoo Female Relief Society in an outdoor meeting. The following day, Thursday, September 1, 1842, either “in the large room over the Store” during the morning hours, or “at home attending to business” in the afternoon, Joseph wrote his first letter to the Church about baptism for the dead. [35] To all appearances, life for Joseph seemed to be returning to normal.

Joseph evidently planned to read this September 1 letter himself to the assembled Saints the following Sunday, but such was not to be. The day after writing the letter, Joseph received word “to the effect that the Sheriff with an armed force, was on his way to Nauvoo.” More bad news arrived the next morning, Saturday, in the form of a letter from David Hollister, who informed Joseph “that the Missourians were again on the move.” Then, while Joseph was having lunch with his family shortly after noon that same day, three officers—including James Pitman and Edward Ford, two of the authorities who had helped arrest Joseph and Rockwell on August 8—arrived at his home, having reached it “on foot, undiscovered until they got into the house,” by coming up the river and hitching their horses below the partly constructed Nauvoo House. While John Boynton, who was visiting Joseph that day, stalled for time, Joseph quietly left the house through a back door and made his way to the red brick store. Later in the evening he moved to the home of Edward Hunter, where he stayed until returning home seven days later on September 10.[36]

With Pitman, Ford, and others in the neighborhood watching for their chance, Joseph was unable to read the letter on baptism for the dead to Church members on Sunday, September 4. Rather than postpone its delivery, though, Joseph sent it to William Clayton with the request that it be read at the meeting. Clayton saw that Joseph’s instructions were followed, and while he did not record who actually read the letter to the Church, he did note that its contents “cheered their hearts and evidently had the effect of stimulating them and inspiring them with courage, and faithfulness.”[37] At some point, too, Clayton began copying the letter into Joseph Smith’s journal, which was being kept at that time in “The Book of the Law of the Lord”—a large (17 x 11 x 2.25 inches), leather-bound volume in which donations for constructing the Nauvoo Temple were also recorded.[38] Clayton copied approximately half of the letter’s first sentence (through “or coloring of justice, or right”) under the date of September 4, 1842, in Joseph’s journal before turning the task over to Eliza R. Snow, a plural wife of Joseph Smith who was living with the Smith family at the time.[39] Snow copied the remainder of the letter, including Joseph’s name at the end, into the journal. Clayton also made a separate copy of the letter himself at some point, and the Times and Seasons published a copy of it in the September 15, 1842, issue of the paper under the title “Tidings.”[40] All of this is to say that in spite of the adverse conditions under which this letter was produced—or, perhaps, because of those conditions—multiple copies of this letter were in existence within days of its delivery to the Church on September 4. The letter entered Mormon canon two years later as section 105 of the 1844 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants.[41]

The letter’s contents suggest that Joseph wrote much of it after his narrow escape on September 3. As we have seen, Joseph was not in hiding the day the letter is dated—September 1, 1842—and he had recently made two public appearances, including one with the Nauvoo Female Relief Society just the day before. Yet the letter opens and closes with references to his flight, making it clear that he is on the run at the time of writing. Quite possibly he began writing the letter on September 1 or wrote an early draft of it on that date and then rewrote or amended it without changing the date after his circumstances deteriorated on September 3.

Joseph closed this letter by telling the Saints that he would “write the Word of the Lord from time to time” on the subject of baptism for the dead and other topics, and send such writings to them by mail.[42] He was not long in making his promise good. On September 7, 1842, just three days after his first letter was read publicly, Joseph—still in hiding at Edward Hunter’s home—dictated his second letter on baptism for the dead, and “ordered [it] to be read next Sabbath.”[43] Four days later, accordingly, assembled Church members heard this second letter, “[t]he important instructions” of which, Clayton recorded, “made a deep and solemn impression on the minds of the saints.”[44] As with the first letter, multiple copies of this letter were quickly made: Eliza R. Snow copied it in its entirety into Joseph’s journal under the date September 11, 1842—the day it was read—in “The Book of the Law of the Lord,” Clayton made a separate copy, and a copy was published in the October 1, 1842, issue of the Times and Seasons.[45] Two years later, the letter was published as section 106 of the 1844 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants.[46] All of these copies date the letter to September 6, but Joseph’s journal clearly indicates that it was dictated on September 7.[47]

Joseph had returned home the night before the second letter was read to the Church, but it was another two weeks before he appeared in public.[48] A letter he wrote to James Arlington Bennet the day after he dictated the September 7 letter betrays the frustration he was feeling during this second period of hiding—frustration which the celebratory tone of his letter to the Church courageously and completely masks. “I am now hunted as an hart, by the mob,” he wrote to Bennet, “under the pretence or shadow of law, to cover their abominable deeds.” After briefly rehearsing the charges against him, and noting his well-documented presence in Nauvoo the day Boggs was shot, he continued:

The Governor of the State of Illinois . . . has now about thirty of the blood-thirsty kind of men in this place, in search for me; threatening death and destruction, and extermination upon all the Mormons; and searching my house almost continually from day to day; menacing and threat’ning, and intimidating an innocent wife and children, & insulting them in a most diabolical manner; threatening their lives, . . . saying they will have me dead or alive; and if alive, they will carry me to Missouri in chains, and when there, they will kill me at all hazards. And all this is backed up, and urged on, by the Governor of this State, with all the rage of a demon; putting at defiance, the Constitution of this State—our chartered rights—and the Constitution of the United States: For not as yet, have they done one thing that was in accordance to them. . . . When shall the oppressor cease to prey and glut itself upon innocent blood! Where is Patriotism? Where is Liberty? Where is the boast of this proud and haughty nation? O humanity! where hast thou fled? Hast thou fled forever?

Joseph continued in the same vein line after line after line, to the point that the “short relation” of his circumstances to Bennet now occupies two full pages of the large Book of the Law of the Lord. Even then, he admitted, “I cannot express my feelings.”[49]

Joseph tentatively came out of hiding at the end of September, only to learn, again, that his hopes were premature. On September 19, 1842, after seven weeks of failure on the part of officers from both Missouri and Illinois to capture Joseph themselves, Missouri governor Thomas Reynolds offered a reward of three hundred dollars to anyone who could capture either Joseph or Orrin Porter Rockwell, and six hundred dollars for the capture of both.[50] Not to be outdone, Illinois governor Thomas Carlin issued a “Proclamation” the following day, September 20, 1842, offering a reward of two hundred dollars “to any person or persons, for the apprehension and delivery” of Joseph or Rockwell to the authorities.[51] News of the rewards reached Nauvoo on October 2, and it was followed five days later by a report that “many of the Missourians were coming to unite with the Militia of this State [Illinois], voluntarily and at their own expense” to search Nauvoo if Joseph was not arrested elsewhere. The Prophet and his associates initially tried to downplay the potential effectiveness of the rewards and the reliability of the report about the Missourians, but eventually concluded “[f]rom the situation and appearance of things abroad” that Joseph should leave home “untill there should be some change in the proceedings of our enemies.”[52] Joseph spent most of the remainder of the month at the home of James Taylor—father of John Taylor—on the Henderson River some thirty miles northeast of Nauvoo, and returned home on October 28. “From the appearance of thinks [things?] abroad,” Clayton wrote after Joseph’s arrival in Nauvoo, “we are encouraged to believe that his enemies wont trouble him much more at present.”[53]

Joseph’s reading of the situation proved correct, with November and the first part of December 1842 passing by uneventfully. As a fugitive with a price on his head, however, Joseph’s only hope of finding lasting security was through due process of the law. An opportunity to do so safely first presented itself in mid-December, when Illinois State Supreme Court justice Stephen A. Douglas suggested to some of Joseph’s supporters that they petition newly elected Illinois governor Thomas Ford to revoke Carlin’s warrant and proclamation for Joseph’s arrest. With the help of Justin Butterfield, US district attorney for Illinois, Joseph’s associates immediately prepared and presented such a petition to Ford, who, unsure of his authority to “interfere” with Carlin’s official acts, asked the six justices of the state Supreme Court who were in the area how he should proceed. All six agreed, Ford wrote to Joseph later, “that the requisition from Missouri was illegal and insufficient to cause your arrest, but were equally divided as to the propriety and Justice of my interference with the acts of Governor Carlin.” Not wishing “to assume the exercise of doubtful powers,” Ford recommended that Joseph “submit to the Laws and have a Judicial investigation of your rights” and promised Joseph protection should he find it necessary to go to Springfield to do so. Butterfield, in his own letter to Joseph, seconded Ford’s counsel and told him that he (Butterfield) could bring the case up on a writ of habeas corpus before either the Illinois Supreme Court or the Circuit Court of the United States for the District of Illinois. “I will stand by you and see you safely delivered from your arrest,” the district attorney promised.[54]

With the district attorney of Illinois, all available justices of the Illinois Supreme Court, and the new governor of Illinois all on his side, Joseph’s fortunes had clearly turned. Their immediate and decisive support also validates Joseph’s claim that the proceedings against him were blatantly illegal and calls into question—as Joseph also had—the motives of Thomas Carlin and other officials in their pursuit of Joseph when the case against him was so obviously problematic. Of more immediate concern to Joseph, though, was the glimmer of hope such support provided, which he wasted no time acting upon. Taking Ford and the others at their word, Joseph and several of his friends left Nauvoo two days after Christmas for Springfield, where they arrived on December 30, 1842. Joseph made the trip in the custody of his friend Wilson Law, who had arrested him on the authority of Carlin’s September 20 proclamation in order to prevent someone else from doing the same as they traveled.[55] After Joseph arrived in Springfield, Ford issued a new arrest warrant against him that replaced Carlin’s original August 2, 1842, warrant and allowed Joseph to be arrested by William F. Elkin, sheriff of Sangamo County, Illinois, to whom a writ of habeas corpus on Joseph’s behalf could then be issued.[56]

Other cases and delays prevented Joseph’s habeas corpus hearing from being held for another five days, by which time Justin Butterfield, who was serving as Joseph’s legal counsel, had decided that the Federal Circuit Court was the appropriate court for the hearing, since extradition was a constitutional issue.[57] When Joseph’s case was finally called up on January 4, 1843, before Judge Nathaniel Pope, Butterfield argued for Joseph’s discharge from arrest on the grounds that Missouri governor Thomas Reynolds’s requisition to Illinois governor Thomas Carlin had misrepresented the contents of Boggs’s affidavit. Boggs had accused Joseph of being an “accessory before that fact” and a “resident of Illinois,” Butterfield pointed out, but had said nothing that would justify Reynolds identifying Joseph as a “fugitive from justice” who had committed a crime in Missouri and then fled to Illinois.[58]

The final validation for Joseph’s position came the following day in the official decision of Judge Nathaniel Pope, who fully agreed with Butterfield’s assessment of the situation:

It must appear that he [Joseph] fled from Missouri to authorise the Governor of Missouri to demand him. . . . The Governor of Missouri, in his demand, calls Smith a fugitive from justice . . . [and] expressly refers to the affidavit as his authority for that statement. Boggs, in his affidavit, does not call Smith a fugitive from justice, nor does he state a fact from which the Governor had a right to infer it. . . . [T]he governor [Reynolds] says he [Joseph] has fled to the state of Illinois. But Boggs only says he is a citizen or resident of the state of Illinois. . . . For these reasons, Smith must be discharged.[59]

After reviewing Pope’s opinion, Thomas Ford issued an official order the following day, January 6, 1843, discharging Joseph from arrest and certifying “that there is now no further cause for arresting or detaining Joseph Smith therein named by virtue of any proclamation or executive warrant heretofore issued by the Governor of this state.”[60] Joseph was free.

In the end, the case against Joseph was a casualty of its own illegality—an illegality that was evident to everyone who examined it with an unbiased eye. Unfortunately for the Prophet and his friends, it had taken five months before such people could be found in Illinois’s legal system. With the searches, the hiding, the rumors, and the threat of returning in chains to Missouri, the ordeal had been a difficult one for everyone involved. But it had not prevented Joseph from filling his role as a prophet. The two letters he wrote to the Church during this time provided the doctrinal and procedural foundation upon which the Church initiated its practice of baptism for the dead, and upon which it continues the practice today in temples around the world. As dark and frightening as this five-month period was, it had not stopped the work of the Restoration from rolling forward.

Notes

[1] Joseph Smith first taught about baptisms for the dead at the funeral of Seymour Brunson on August 15, 1840, and members of the Church were performing such baptisms in the Mississippi River by September of that year. Records of these early baptisms had been inconsistently kept, however, and had not included names of eyewitnesses. Simon Baker, “15 August 1840 Minutes of Recollection of Joseph Smith’s Sermon,” Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library; Jane Neymon and Vienna Jacques, statement, November 29, 1854, Historians Office, Joseph Smith History Documents, Church History Library; Nauvoo Temple, record of baptisms for the dead, 1841–1845, Church History Library. For more on the early history of baptisms for the dead, see Alexander L. Baugh, “‘For This Ordinance Belongeth to My House’: The Practice of Baptism for the Dead Outside the Nauvoo Temple,” Mormon Historical Studies 3, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 47–58.

[2] Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Richard Lloyd Anderson, eds., Joseph Smith to “all the saints in Nauvoo,” September 1, 1842, copied in Joseph Smith, journal, September 4, 1842, in Journals, Volume 2: December 1841–April 1843, vol. 2 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2011), 131 (hereafter cited as JSP, J2).

[3] Smith, journal, September 3, 1842, in JSP, J2:125.

[4] Joseph Smith to “the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” September 6 [7], 1842, copied in Smith, journal, September 11, 1842, in JSP, J2:143–50.

[5] Smith, journal, May 6, 1842, in JSP, J2:54. While the Masonic lodge in Nauvoo held a meeting on the evening of May 6, 1842, Joseph’s name does not appear on the list of attendees. Justin Butterfield, however, who represented Joseph at the January 4, 1843, habeas corpus hearing in Springfield, Illinois, reported that he had, in fact, been present. See Nauvoo Masonic Lodge Minute Book, May 6, 1842, Church History Library; Smith, journal, January 4, 1843, in JSP, J2:222.

[6] Smith, journal, May 7, 1843, in JSP, J2:54–55.

[7] David Kilbourne to Thomas Reynolds, May 14, 1842, Thomas Reynolds, Office of Governor, Missouri State Archives; Smith, journal, May 14, 1842, in JSP, J2:57.

[8] “Assassination of Ex-Governor Boggs of Missouri,” Quincy Whig, May 21, 1842.

[9] Joseph Smith, May 22, 1842 Letter to the Editor, in Quincy Whig, June 4, 1842.

[10] The First Presidency, nine members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and three bishops in Nauvoo had “withdraw[n] the hand of fellowship” from Bennett on May 11, 1842, “he having been labored with from time to time, to persuade him to amend his conduct, apparently to no good effect.” “Notice,” Times and Seasons, June 15, 1842, 3:830. See also “To the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints,” Times and Seasons, July 1, 1842, 3:839–843, and “John C. Bennett,” Times and Seasons, August 1, 1842, 3:868–78.

[11] John C. Bennett, letter, June 27, 1842, in Sangamo Journal, July 8, 1842

[12] John C. Bennett, letters, July 2 and 4, 1842, in Sangamo Journal, July 15, 1842

[13] Lilburn W. Boggs, affidavit, July 20, 1842, in JSP, J2:379–80. Boggs’s affidavit regarding Rockwell is referenced in Orrin Porter Rockwell, petition for writ of habeas corpus, August 8, 1842, copy, Nauvoo, IL, Records, Church History Library.

[14] United States Constitution, article 4, section 2.

[15] Thomas Reynolds, requisition, July 22, 1842, in JSP, J2:380–81.

[16] Joseph Smith, petition for writ of habeas corpus, August 8, 1842, copy, Nauvoo, IL, Records, Church History Library; Rockwell, petition for writ of habeas corpus, August 8, 1842, copy, Nauvoo, IL, Records, Church History Library

[17] Smith, journal, August 8, 1842, in JSP, J2:81.

[18] Smith, petition for writ of habeas corpus, August 8, 1842; Rockwell, petition for writ of habeas corpus, August 8, 1842.

[19] Writ of habeas corpus for Joseph Smith, August 8, 1842, copy, Nauvoo, IL, Records, Church History Library; writ of habeas corpus for Orrin Porter Rockwell, August 8, 1842, copy, Nauvoo, IL, Records, Church History Library.

[20] Smith, journal, August 8, 1842, in JSP, J2:81. Clayton kept Joseph’s journal from June 30 through December 20, 1842. JSP, J2:xiii–xv.

[21] “Persecution,” Times and Seasons, August 15, 1842, 3:888.

[22] Carlin did not believe that the Nauvoo Municipal Court had authority to issue a writ of habeas corpus in a case like Joseph’s and Rockwell’s where “persons [were] held in custody under the authority of writs issued by the courts, or the executive of the State.” Thomas Carlin, Quincy, IL, to Emma Smith, Nauvoo, IL, September 7, 1842, copied into Smith, journal, September 11, 1842, in JSP, J2:151–52.

[23] Orrin Porter Rockwell per S. Armstrong, Philadelphia, PA, to Joseph Smith, Nauvoo, IL, December 1, 1842, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library; Smith, journal, March 13, 1843, in JSP, J2:307.

[24] Smith, journal, August 10 and 13, 1842, in JSP, J2:83, 86.

[25] Smith, journal, August 11–29, 1842, in JSP, J2:83–24.

[26] Smith, journal, August 11, 1842, in JSP, J2:83–84.

[27] Smith, journal, August 12, 1842, in JSP, J2:85.

[28] Smith, journal, August 13, 1842, in JSP, J2:86.

[29] Smith, journal, August 13 and 14, 1842, in JSP, J2:86, 89–90.

[30] Smith, journal, August 11, 1842, in JSP, J2:83–84.

[31] Smith, journal, August 13, 1842, in JSP, J2:85–86.

[32] Smith, journal, August 15, 1842, in JSP, J2:90, 92.

[33] Joseph Smith, Headquarters of the Nauvoo Legion, to Wilson Law, Nauvoo, IL, August 15, 1842, copied in Smith, journal, August 14, 1842, in JSP, J2:87–88.

[34] Joseph Smith, Nauvoo, IL, to Emma Smith, Nauvoo, IL, August 16, 1842, copied in Smith, journal, August 21, 1842, in JSP, J2:107–9.

[35] Smith, journal, August 23, 26, 29, 31 and September 1, 1842, in JSP, J2:119–20, 122–24.

[36] Smith, journal, September 2, 3, and 10, 1842, in JSP, J2:124–26, 143.

[37] Smith, journal, September 4, 1842, in JSP, J2:131, 133.

[38] For a photograph and detailed description of “The Book of the Law of the Lord,” see JSP, J2:210.

[39] Joseph Smith to “all the saints in Nauvoo,” September 1, 1842, copied in Smith, journal, September 4, 1842, in JSP, J2:131, n. 449. Snow was sealed to Joseph Smith as a plural wife on June 29, 1842, and lived with the Smith family from August 18, 1842 to February 11, 1843. Eliza R. Snow, affidavit, Salt Lake Co., Utah Territory, 1869, in Joseph F. Smith, Affidavits about Celestial Marriage, 1:25, Church History Library; Eliza R. Snow, journal, August 14 and 18, 1842, February 11, 1843, Church History Library.

[40] Revelation Collection, Church History Library; “Tidings,” Times and Seasons, September 15, 1842, 3:919–20.

[41] Robin Scott Jensen, Richard E. Turley Jr., and Riley M. Lorimer, eds., Revelations and Translations, Volume 2: Published Revelations, vol. 2 of the Revelations and Translations series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2011), 678–80. Hereafter cited as JSP, R2.

[42] Joseph Smith to “all the saints in Nauvoo,” September 1, 1842, copied in Smith, journal, September 4, 1842, in JSP, J2:133.

[43] Smith, journal, September 7, 1842, in JSP, J2:137.

[44] Smith, journal, September 11, 1842, in JSP, J2:150.

[45] Joseph Smith to “the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” September 6 [7] ,1842, copied in Smith, journal, September 11, 1842, in JSP, J2:143–150; Revelation Collection, Church History Library; “Letter from Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons, October 1, 1842, 3:394–396.

[46] JSP, R2:680–690.

[47] The journal entry under September 6 notes that Joseph counseled various members of the Twelve about a mission assignment and worked with William Clayton and Newel K. Whitney on a business transaction, and that “nothing of special importance transpired” in the evening. The September 7 entry notes that Joseph “wrote—or rather dictated a long Epistle to the Saints which he ordered to be read next Sabbath and which will be recorded under that date.” Smith, journal, September 6 and 7, 1842, in JSP, J2:133, 137.

[48] Smith, journal, September 10–25, 1842, in JSP, J2:143–159.

[49] Joseph Smith, Nauvoo, IL, to James Arlington Bennet, September 8, 1842, copied in Smith, journal, September 8, 1842, in JSP, J2:137–143; quotes from pages 139 to 141.

[50] Buel Leopard and Floyd C. Shoemaker, comp., The Messages and Proclamations of the Governors of the State of Missouri, vol. 1 (Columbia, MO: State Historical Society of Missouri, 1922): 524–25.

[51] Thomas Carlin, proclamation, September 20, 1842, reproduced in JSP, J2:381–82.

[52] Smith, journal, October 2 and 7, 1842, in JSP, J2:160, 162.

[53] Smith, journal, October 10, 20, 21, and 28, 1842, in JSP, J2:163–64.

[54] Smith, journal, December 9–20, 1842, in JSP, J2:174, 177–81.

[55] Smith, journal, December 26, 27, 30, 1842, in JSP, J2:193–95, 197.

[56] Smith, journal, December 31, 1842, in JSP, J2:200–204; arrest warrant, Thomas Ford to William F. Elkin, December 31, 1842, in JSP, J2:383–385; Joseph Smith, petition for writ of habeas corpus, December 31, 1842, in JSP, J2:385.

[57] Smith, journal, January 4, 1843, in JSP, J2:219.

[58] “The Release of Gen. Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons, January 2, 1843, 4:60.

[59] Court ruling, January 5, 1843, in JSP, J2:397, 401. For a detailed analysis of this hearing and its legal context, see Jeffrey N. Walker, “Habeas Corpus in Early Nineteenth-Century Mormonism: Joseph Smith’s Legal Bulwark for Personal Freedom,” BYU Studies 52, no. 1 (2013):4–97.

[60] Thomas Ford, order discharging Joseph Smith, January 6, 1843, in JSP, J2:402.