Improving Learning and Teaching: A Conversation with Russell T. Osguthorpe

Barbara Morgan Gardner

Barbara E. Morgan, "Improving Learning and Teaching: A Conversation with Russell T. Osguthorpe, Religious Educator 15, no. 3 (2014): 77–89.

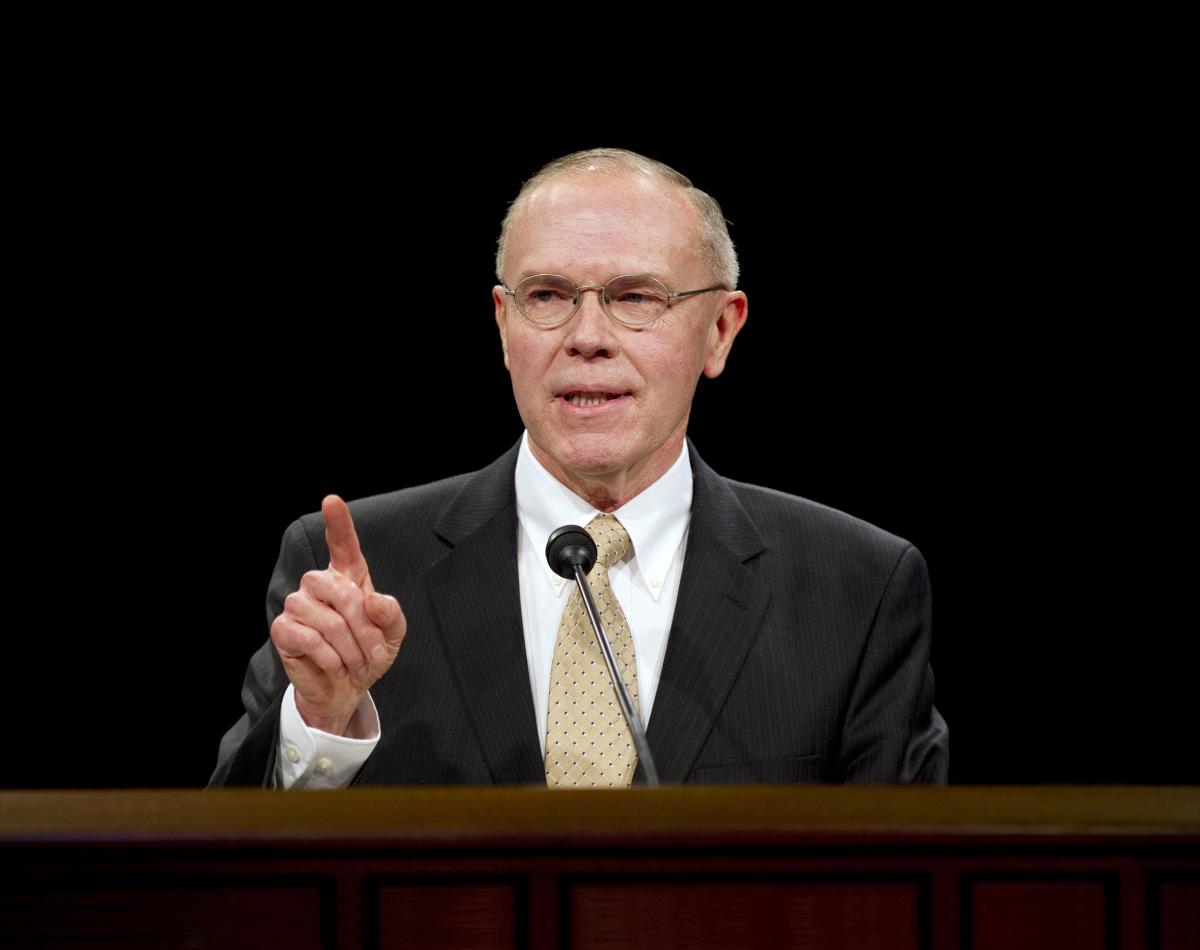

Russell T. Osguthorpe (russell_osguthorpe@byu.edu) is a former Sunday School general president and a professor emeritus of instructional psychology and technology at the David O. McKay School of Education, BYU. He and his wife had been recently called as president and matron of the Bismarck North Dakota Temple when this article was published.

Barbara E. Morgan (barbara_morgan@byu.edu) was an assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU, serving as institute director and coordinator for Seminaries and Institutes in Cambridge, Massachusetts when this article was written.

"I've always wondered about people who love listening to themselves talk...Teaching is not just talking. Teaching is helping someone else learn, and that means understanding them form their point of view." Photo courtesy of BYU Photo

"I've always wondered about people who love listening to themselves talk...Teaching is not just talking. Teaching is helping someone else learn, and that means understanding them form their point of view." Photo courtesy of BYU Photo

Morgan: How did you receive your calling as the Sunday School general president?

Osguthorpe: I walked through the door to meet with President Thomas S. Monson, and he said, “Well, you’ve got broad shoulders; that’s good!” I thought, “Uh-oh.” After calling me to be the Sunday School general president, during my orientation, Elder Russell M. Nelson said, “You are responsible to help improve learning and teaching in the Church throughout the world.” Later my presidency had an orientation with the First Presidency. In this meeting we were told that the teacher development program had been changed and that responsibility for teaching and learning had been given to the Sunday School. The Sunday School president is now responsible to help improve learning and teaching in the home, in the auxiliaries, and in the priesthood in the Church throughout the world. It is a little daunting to say the least. It was interesting that the emphasis was not only placed on teaching, but on learning.

Morgan: What led up to this new curriculum change for youth?

Osguthorpe: In December of 2009, Elder Neil L. Andersen, who was called at the same time we were, held a meeting where he invited the Young Men president, the Young Women president, the Sunday School president, and Elder Paul B. Pieper, who is now the executive director of the Priesthood Department, to meet with him. He asked if we could suggest several options that the Brethren could consider for updating, revising, and improving the youth curriculum. So we started meeting, often and long, the three auxiliary presidents, Elder Pieper, and staff members.

In one of the meetings, I had Brother David L. Beck sitting on one side of me and Sister Elaine S. Dalton on the other. I said, “I’ve got all of your young men, and I’ve got all of your young women during second block. Why don’t we do this all together and revise our curriculum for Sunday School at the same time that we’re revising the Young Men and Young Women curriculum?” They replied with an enthusiastic, “Great!” In one of the meetings I said, “It seems like Sunday School ought to be serving your needs in Young Men and Young Women. What we ought to be doing in Sunday School is helping young people learn how to learn the gospel and learn how to teach it. Among other things, this will improve their work with Duty to God for Young Men and Personal Progress in Young Women.” David Beck jabbed me and said, “Now you’re talking!” In these early meetings, there was enormous unity from the very beginning about what we wanted to have happen. Sister Dalton wasn’t heading down one way and David Beck the other way and me my own way. No. We all wanted to help youth become more converted to the gospel.

The joining of these auxiliaries to work together on this curriculum was a miracle. We eventually met together with seminaries and institutes on the improvement of teaching and learning and deciding upon doctrines to be studied. Elder Paul V. Johnson was key to having this happen, because he was very open and excited about it. He was excited that the Church was trying to do something on Sundays to help the youth learn more effectively. So many people with so many vested interests coming together for the purpose of the whole was an organizational miracle.

None of this could have happened without Elder Robert D. Hales, who chaired the Priesthood Executive Council at that time. I have never felt such an intensity of commitment from anyone. You could tell he was going to do what the Lord wanted done. He was a man on a mission. Here he is with a body that is not cooperating with him—all kinds of health difficulties—yet he has a strength of spirit that is almost unfathomable. In our meetings he would often encourage us to do what we needed to do to receive our own revelation regarding the new curriculum. He knew we needed a new youth curriculum. He knew we needed to help the youth so that we could strengthen them for the rest of their lives. He could see that the curriculum needed to be revised in order to do this. The job of our auxiliaries and the seminary was to figure it out by receiving inspiration and counseling together about the promptings as they came.

The ultimate desired outcome was eternal life and exaltation for these youth. We wanted learning and teaching for conversion, not just in the classrooms on Sundays but every day in their homes and in their lives. When people look at the new curriculum, they will see that we’re actually trying to help youth make changes so that they can grow and improve and be stronger. This is a different kind of gospel instruction than simply listening to stories and experiences that might be nice but that may not encourage a person to make any changes. The Lord is helping us understand that gospel instruction and learning are very unique. This isn’t about increasing active learning. It’s deepening learning. It is not just mastering facts. It is changing the way we live.

One of the things I’m very excited about is the delivery system. There’s now an online delivery system for the first time in the Church. It’s modifiable; it’s changeable. We can improve it over time. We can look at experiences that people have around the world, and we can gradually strengthen this curriculum. To do that with hard-copy manuals is almost impossible given the nature of translation in the Church. We can’t just take a manual and make all these changes. Our curriculum is the scriptures, the teachings of the prophets, the Ensign, or the Liahona. The learning resources are ways to help teachers teach that curriculum to the youth and their children in ways that they will understand. Many miss the long stories and the scripted lessons, but this old way caused immense translation problems. We now have a living curriculum. We’ve never had a living curriculum before.

Morgan: What have you learned over the last year as you have evaluated the program and curriculum?

Osguthorpe: I asked the youth at a stake fireside I was speaking at what they thought about it. A girl raised her hand and said, “The biggest difference is that I feel like what I say matters. My thoughts are important.” Teachers are actually valuing the comments of the class members rather than rushing to get through the material. The youth contribute much more than they used to and are gaining a more in-depth understanding of the doctrines. There is more skill development going on, which could lead to better missionaries and better parents when the youth get older. By skill development, I mean that they are able to use the scriptures, understand them, liken them, apply them, and teach them.

One of the first things that teachers mention when we ask them for feedback on the new curriculum is how much they appreciate the flexibility. They can decide whether or not to continue a lesson an additional week, and they can decide which lesson to teach. This is one thing we have quantitative data on through analytics on the website. It is well documented that after the first year, teachers are not choosing the same lessons in the same order. And when you look at some of the choices they are making, you can see that in a Beehive class or in a deacon class they might be choosing different lessons than they would if they’re teaching the Laurels or priests. These are very positive data. Teachers are taking advantage of and appreciating the flexibility.

There is also a better understanding of the role of a teacher. If I see my role as to deliver what’s in the manual, then that’s what I’ll do. And if I’ve delivered that content, whether or not they learn it—that’s up to them, but my job is to deliver it. The reason we have difficulty is we do not understand how people learn. People need time to reflect; they have to use what they are thinking about. We use the fire hose approach all the time, forcing information and content and not caring about what is being learned. Some people think that having the students read the scriptures is participation. That is not participation. That is them delivering the teacher’s preconceived content. Participation is when some expression, some unique contribution is coming out of them. It needs to come out of them. They need to be articulating what’s happening inside of them. When teachers say, “read this quote, now read this quote, now this quote,” that’s the teacher’s content; that’s not participation, because we learn nothing about the person but only about the verse. Of course we need the scriptures, but we don’t need to be selective. We’ve got to tie the scriptures and the doctrines to life. We must be asking how this doctrine is going to affect our own life. How can this help the learners? How can we live what we have learned during the week? And if a teacher knows nothing about the lives of the learners, the teacher cannot make these ties between doctrine and application.

The real problem is not what happens on Sundays; the problem we have is Monday. The person goes to church on Sunday, three hours minimum, but then Monday they don’t read the scriptures; they don’t say their prayers. They get bombarded with the world and, many times, succumb. As teachers, we must be asking ourselves, “What are we going to do on Sunday to help during the week?” What will we do with email, texts, or anything else, to help the learners stay strong every day? A teacher’s job is more motivational, to get the learner learning and excited. When the youth are asked now about their experiences with the youth curriculum, they say, “It affects me much more during the week than before.”

Another thing that’s strong in the youth curriculum is that they actually remember what they are learning, at least the doctrines. When you ask them what they are learning, they can usually say, “This month we are talking about the Atonement. Last month we talked about the plan of salvation.” This wasn’t happening before. Not only can they tell you the doctrine, but when asked, they can teach you about the doctrine.

Morgan: What are some of the difficulties associated with the new youth curriculum?

Osguthorpe: There is resistance to change on the part of some of the adults. The youth know what needs to happen in the classroom and most of them want it; it’s often the teachers who struggle to let go of the reins. Teachers talk too much and students too little. Some adults want the lessons to be more scripted. What the teachers need to do is listen more and develop observation skills. They need to be observing what the learners need, discerning by the Spirit so that the teacher knows what to say. These are skills that people don’t even think a teacher needs because they see the teacher as doing all the talking, but these are the most important skills. It is more important to be able to listen, observe, and discern than it is to be able to talk. I love hearing teachers say, “I’m learning so much from the class members.” That, I think, is not a comment that would have been frequently made in the previous curriculum.

To watch these young people in action, talking with each other about their understanding and witness of the scriptures and the testimonies they have—there’s nothing like it. Sometimes we underestimate by far what’s inside of them. We need to find ways to help them express what’s inside. These teachers need to show the students how. They need to train them, coach them, and give them feedback so that they can do it. Learners should be practicing with each other while in class. They need to be more engaged. I want to live to see the day when we have more action in the class. Our youth need practice, and they need to be challenged. In Seminaries and Institutes, at the Church universities, and in Sunday School, we need to give them opportunities to perform. Students need to stand up and give a talk, even if it’s only a two-minute talk. We must teach the skill, have them actually do it, and then have the teacher and other students talk about what their strengths were and what we can learn from each experience. This should be happening in class.

Perhaps the biggest misconception that I’ve seen is the idea that the teacher doesn’t need to prepare. Some think that they can turn it over to the youth and just wing it. It was never intended to have the youth do all of the teaching and to turn the lesson completely over to them. I’ve heard some teachers say, “Next week the lesson is yours,” and then the youth, instead of the teacher, deliver content. That doesn’t prepare them. The teacher needs to prepare the youth, to coach the youth, not turn it over to them.

We worry about two different types of teachers. One teacher says, “I don’t think I can do it; it’s too hard.” We need to help that teacher. The other teacher we worry about is the one who says, “Oh, this isn’t anything different than what I’ve been doing.” We need to help that one too.

During the first year, there were those who were so excited to try new things and really work on correct implementation. They’d say, “This is the greatest thing I’ve ever seen, and I’m so excited about it.” Then you’ve got others who say, “Um, I think I need to be released because I can’t do this. I don’t know how to do it, and I can’t do it.” That’s a minority of people, but what are we going to do for those people? How are we going to help them see that this way of teaching is not extremely difficult? It’s different, and it’s more enjoyable for the teacher and the learner than what they’ve been doing. It’s much more enjoyable than looking down at learners whose heads are down on the desks because they’re bored. When they get more engaged, active, open, and committed in a learning setting, it’s going to be better for everybody. But for them to feel that, they’ve got to experience it.

I’ve seen that when teachers don’t understand the youth curriculum, they automatically turn to content delivery. They pull out videos from twenty years ago rather than using the new fabulous videos that are online. They have students read quotes and scriptures, and little thinking is occurring. Some of the students clearly don’t even understand what they are reading, but the teacher has them keep reading just so they are participating and going through content. That pattern is so engrained. Rather than teaching for conversion, they are teaching fact after fact and asking fact-type questions and forcing material. Even with the new curriculum, they sometimes try to force it to fit the old pattern. The problem is some teachers don’t understand that people don’t learn by just sitting there.

Morgan: What experiences have stood out to you as you have traveled throughout the world?

Osguthorpe: In the D. R. Congo there was a young man about sixteen or seventeen years old who gave a talk in the stake conference. He got to the podium, and he said, “I am going to speak today about the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ, and I’m going to talk about my own witness of the Restoration.” After giving a beautiful talk on the Restoration of the Church, he said, “Brothers and sisters, I need to end my talk, but I can’t end without bearing my testimony one more time about Joseph Smith. I’ve got to tell you one more time how much I know he’s a prophet of God.” Then he said, “I know I need to end, but I’ve got to bear my testimony one more time about the Book of Mormon. I know the Book of Mormon is true.” I looked over to the mission president sitting next to me, and I said, “That was one of the most powerful talks I have ever heard from a youth in my life.” It was all coming from him; he wasn’t reading anything. It was powerful. Then we walked outside after the meeting was over, and I saw these three young men, probably nineteen or twenty years old, and we said hello to them. I asked, “How long have you been members of the Church?” They said, “Oh, we’re not members of the Church.” And I said, “Oh, really? But you just went to stake conference.” (I later found out that we had over two hundred investigators at that meeting.)

“Well, he’s getting baptized tonight, and we’re going to get baptized in a week or two,” they responded, pointing at one young man in the group. “So why are you joining this church?” I asked. One said, “Oh, it’s because of the teaching.” I said, “The teaching?” and he said, “Yeah, because in this church, you can ask questions. In the other churches, the minister talks, but you can’t ask questions. In this church, we can ask whatever question we want, and we can get answers. It’s terrific!”

Morgan: In your recent calling and in other assignments, what is your desired hope for learners in a religious setting?

Osguthorpe: We want them to be able to give reason for the hope that is in them. That means we don’t only want them to have knowledge, and we don’t only want them to feel good about the Church; we want them to be able to articulate, convincingly, their testimony of the restored gospel and relate that to everything in their life around them. As a result they will be able to help their children more effectively, teach more effectively, and help people in their ward more effectively when they’re called into leadership positions.

Morgan: What are some specific ways in which you think teaching and learning can be improved?

Osguthorpe: One thing we know about learning is that when we learn new things, we are going to forget them quite rapidly unless we use them to do something. So if they are attached to a skill, for example, we not only retain them, but they get stronger. We don’t just want learning that maintains itself, and we don’t want learning that only lasts. We want learning that grows. We want learning that keeps growing, and by that I mean people keep building on what they’ve learned and get more proficient, more knowledgeable, and more capable with every passing day. We’ve got to understand things, but for what purpose? What is it going to lead to? How are they going to use this? What skills are they going to develop with that knowledge?

When we focus on large bodies of content and try to transfer this content into somebody else’s head, it’s not the most effective kind of learning. When I learn something new, it is usually because I am trying to achieve some kind of goal, and I don’t know how to do a certain thing. So I go get help, either online or from a colleague, and I say, “How do you do this?” They usually have to show me only once because I’m engaged; they’re answering a question that I care about that leads to a real desired outcome. Now you’ve got learning that’s growing, and it will continue to grow because you’ll keep wanting to do new things. This is what Joseph [Smith] did. The whole D&C is just one question and answer after another as Joseph took questions from his heart to the Lord.

I’m not saying we don’t need any structure in our courses and classes, and I’m not saying we don’t need learning outcomes. I think the learning outcomes can be very helpful. But when things get so rigid and pre-scripted, and when a teacher thinks, “Wow, I have got to expose students to all of this content,” we usually don’t have great learning going on.

A chemistry professor I spoke to recently on BYU campus ran into a former student that he had taught a couple of semesters before. He stopped her and asked, “Hey, just out of curiosity, what stuck with you from that course?” She replied, “Oh, from chemistry?” And he said, “Yes.” She said, “Uh, nothing.” Right then and there, on the sidewalk, with his chemistry book in hand that had 1,353 pages, he said to himself, “This chemistry book is hard to lift, and it probably cost a lot. I should not be trying to cover everything in that book. You can’t learn that much. I’ve been trying to cover it all, and nothing sticks.” So how would it stick more? For me, there’s basically only one way, and I don’t think it has to do with discussion technique or how good your syllabus is. I think it has to do with how much you are building the knowledge pieces into skills and actually having students use the knowledge to do something. When they use knowledge to do something, they remember it, and it grows because then they want to move to the next level.

Morgan: How would you translate that into a religious education setting?

Osguthorpe: The gospel is something we live and something we teach. Religion classes could be a constant practicum for students in both teaching and living the gospel. Students’ ability to teach and live the gospel could be elevated tremendously. In religion classes teachers focus primarily on the mastery of content, but it is helping students learn to teach and live that is most important. Teaching students in a religion class to learn as well as to teach is critical.

Teaching is like coaching. As a coach you know more than the players about how to execute plays, but it’s the players who have to execute those plays. Your job is to help those players perform at their maximum potential. You’re pulling for them all the time. You want them to do their very best. A coach does not grade on a curve. He’s not thinking, “I need a certain number of players to perform in the lowest quartile so that I have a good spread.” What he’s thinking is, “I want every player to do well.” We want teachers, like coaches, who stay awake at night wondering how to help a struggling student do better following a poor performance. Too many teachers get into the classroom and think, “Now it’s my job to deliver the content, and if they pick it up, fine; if they don’t, fine.” We could have a video deliver all of the content. We don’t need a live person to do that. We really don’t. Let’s just deliver that online. But if we’ve got a live human being in the classroom, we can have interaction, love between students and faculty, and mentoring: people pulling for each other like the coach does for his or her players.

Morgan: How do you balance the amount of time to cover the material with allowing time for students to practice?

Osguthorpe: For me it’s not hard. I don’t try and deliver much content during class. I try and deliver content out of class. So I say, “Download this talk from conference, listen to it, and then when you come to class, we are going to practice teaching a principle from that talk to each other. Read the scriptures outside of class, and when you come to class, be prepared to teach a principle of the gospel and bolster it with sacred text.” In most classes today, class time is the place to deliver content and outside of class is the place to practice. But we could flip-flop it for the most part because now online they can get whatever content they need. Why not put your excellent lectures online? I remember one time I went to Susan Easton Black, and I said, “I was in Colorado listening to your talk about John Taylor, and I got so involved in it I missed my exit and had to take about an extra half hour.” I was just joking with her, you know, but I didn’t have to be in that class to hear her. I could hear it in my car.

I’ve always wondered about people who love listening to themselves talk. If we think teaching is talking, we are wrong. Teaching is not just talking. Teaching is helping someone else learn, and that means understanding them from their point of view. One of the reasons at conference that we talk to teach is because we cannot possibly have participation with five million people listening. Talking becomes the only way for us to convey a message. I don’t call that teaching; I call that speaking, presenting, preaching, or testifying. That is when we do not have the option of participation. But when we have the option of participation, oh, I want to use it every time. The most interesting thing to me in teaching is not the content that I talk about. It is the learners. It’s what the learners bring to the learning situation, and sometimes they surprise you so much because they have comments or ways of thinking about things that you’ve never thought of in your life. That can cause everyone in the room to take a second look at their own perspective and views. Straight lecture in a classroom, to me, just seems like we are wasting an opportunity to benefit from being together.

I do not mean that we have to turn the whole class over to the students. Students don’t like that, really; students want to hear what the teacher has to say. But they also want to be able to process it in a way that it will change their life. So that means they need to react to it, they need to work with it, they need to break down into groups or do something with it so that they can really internalize it. It’s hard for most people to internalize when they’re only listening.

Morgan: What are some things you recommend to teachers to become better?

Osguthorpe: It’s important to know that everyone can teach, everyone. So when people say, “Oh, I’m not a good teacher; that’s just not my gift,” well, actually, everyone can teach; every parent needs to be a teacher, first and foremost.

For a person to be a better teacher, they have to want to be a better teacher. They have to decide to do better. They process what is going on and get feedback from their peers and those they are teaching. Then they take this feedback and make actual changes in their teaching. If you don’t make any changes based on the feedback, of course you’re not going to get any better. No teacher wants to teach poorly, but some teachers, unfortunately, may say, “I know I’m not doing very well, but I tried before, and I’ve risked, and it hasn’t worked. I’m just going to keep on going like this.” That is, for me, very sad when anybody does this in any walk of life. We have resources here at the universities, in Seminaries and Institutes, and in the Church to help people teach better.

Morgan: Is there a curriculum in the making for the adults?

Osguthorpe: As Elder Jeffrey R. Holland says, “One miracle at a time.” There is great need for a change in adult curriculum, and we are working on it. The adult curriculum is going to be similar to the youth curriculum. It’s being piloted now. It will likely be called “Come, Follow Me,” but that is yet to be determined. There will be much more flexibility than what is currently being used in the adult curriculum. Right now, when you ask an adult what they are learning, if they remember at all, they reference a book but rarely a doctrine or principle. Sometimes they can remember a story, but they may not be thinking of applying a truth as a result. More responsibility will be given to Relief Society and quorum presidencies on what and how to teach so that they can become more involved in the work of salvation. There will be more focus on application of doctrines.

When adults go to Gospel Doctrine class we want them to be able to talk about what doctrines they are learning. When asked what they learned, rather than having them say, “We learned about Abraham and Isaac,” they will say, “We learned about the Abrahamic covenant and why it matters to my family.” We only have about thirty minutes. There is not enough time to talk about everything to do with Abraham and Isaac, so during that time they need to dig in and find out what they have questions about.

As we are piloting the new adult curriculum, we are seeing that the adult classes are getting smaller. More classes are being taught at the same time to decrease the class size. This allows for more participation. I’ve visited many adult classes in the past that are held in the chapel where the teacher uses a microphone. This is rarely conducive to effective teaching and learning. People need to have a chance to express themselves. We need to be teaching to the needs of the learners, not just what is in the manual. When teachers start realizing this, they naturally go to their bishops and ask for smaller class sizes, which means more classes being taught and more learning taking place.

We are also trying to change the perception of the role of the teacher in adult learning. If the teachers see themselves as the embodiment of all truth and knowledge, then of course it would be intimidating because none of us can answer every question. If teachers, however, see their role as someone who helps others learn—not someone who embodies all the answers and knowledge—real learning begins to take place. In order for a teacher to be able to teach, they do not have to be the world’s finest scriptorian, but it helps if they know how to find answers to gospel questions and help others do the same.

We are also working with the misconception that Gospel Doctrine is a place to talk about things that are difficult to understand and that are barely revealed, if at all. Gospel Doctrine class is not the place for that. Gospel Doctrine is a place where we learn how to live the gospel and put into practice during the week what we are learning. Some feel that they need more meat in their classes. Some say they want to discuss controversial topics. To them I say, “What is your goal in learning about these things? What are you trying to do as a result?” What many people don’t realize is that the obscure things are not the meat. The meat is charity and learning to be charitable and kind with each other. The meat is in the basic doctrines of the gospel; once they learn the real doctrine, they are able to handle the obscurities and think for themselves and better deal with difficult questions that others pose. People are confused with what the meat really is.

Morgan: What are you doing to train teachers in both the youth and adult curriculum?

Osguthorpe: There is a training curriculum now being tested, aimed at assisting all teachers of youth and adults in improving teaching. It is not a course or a class, but rather a setting where teachers counsel together to discuss how to improve teaching and ask personalized questions. The real question is when and where to hold these classes. Right now we are piloting having those teachers who teach the second hour meet together the third hour, and all teachers teaching the third hour get together the second hour. Rather than getting together every week, they would get together every other week or once each month, giving them time to learn, practice, observe, distill, and then discuss and ask questions. The training would reach beyond the classroom at church and even focus on training parents at home.

Morgan: What are your long-term hopes for the youth and adult curriculum?

Osguthorpe: That teaching and learning will eventually start changing in the Church. Teachers will use their agency and do what is best for the learners as they listen to the Spirit. The manual guides the teachers and helps them to think and use their agency. This will hopefully not only reach the youth, but the teachers who are with the youth will take it home and use it with their families in family home evening, and when they are released they will use it in their classes with adults. As we train and teach the adults, we will see a major change in how the gospel is learned, taught, and lived throughout the world, and as a result, we will have more converted Saints.