Sacred Learning

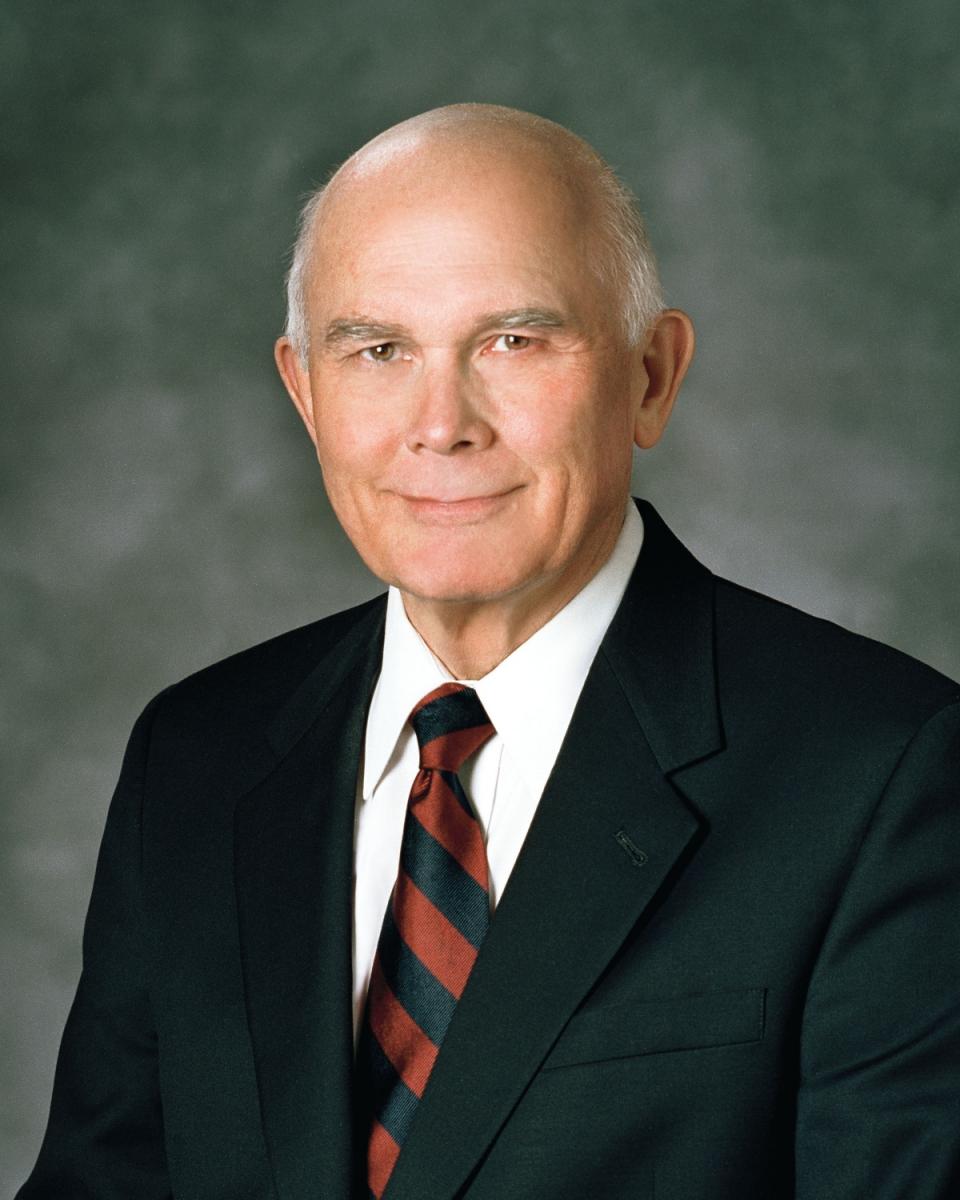

Kevin J Worthen

Elder Kevin J Worthen, "Sacred Learning," Religious Educator 13, no. 3 (2012): 61–77.

Elder Kevin J Worthen was an Area Seventy and advancement vice president at BYU when this was article was published.

This address was given at the BYU Graduate Student Society’s annual banquet on February 16, 2011.

Elder Kevin J. Worthen. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Elder Kevin J. Worthen. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

I’m grateful for the opportunity to address what Elder Dallin H. Oaks once called “the sacred activity” of acquiring knowledge. [1] That activity becomes sacred, in my view, when it completely integrates both scholarship and faith. There are few, if any, universities where it would be more fitting to address this topic. It is true that almost every university has, as part of its mission, the advancement of knowledge through scholarship. It is also true that some universities—though a decreasing number—identify the promotion of religious faith as another of their objectives. However, I know of no other university whose sponsoring religious organization’s commitment to the acquisition of knowledge is so central to its doctrinal foundation.

While some question whether religious faith and true scholarship are compatible, [2] President Brigham Young plainly linked the two together when he stated that “[our] religion . . . prompts [us] to search diligently after knowledge. . . . There is no other people in existence more eager to see, hear, learn and understand truth.” [3] And even that bold pronouncement understates the matter. The Prophet Joseph Smith revealed that the acquisition of knowledge is a matter of the highest import when he taught that “it is impossible for a man to be saved in ignorance” [4] and that “a man is saved no faster than he gets knowledge.” [5]

Thus, LDS theology teaches that the acquisition of knowledge is an essential component of God’s eternal plan for His children. Our ability to achieve the full measure of our divine potential—our very exaltation—is dependent on it. In that light, Elder Oaks’s assertion that “the acquisition of knowledge is a sacred activity” [6] seems to have a deeper meaning. True learning is sacred not only because the activity itself is holy, but also because it refines us and makes us holy.

I wish to address two questions about the sacred activity of acquiring knowledge: First, how can we enhance our ability to engage in that important activity? And, second, how can that enhanced ability help us make important decisions in our lives?

Insights into these and other important questions concerning learning and knowledge are provided in what I consider one of the most instructive and intriguing revelations in all scripture, the 88th section of the Doctrine and Covenants.

As to the first question of how we can enhance our ability to acquire knowledge, I begin with the familiar injunction in the 118th verse of section 88 that we should “seek learning, even by study and also by faith.” This oft-repeated snippet of scripture contains several insights that I believe can help us improve our ability to acquire knowledge.

The first is that religious faith and study (or rational inquiry) are not mutually incompatible. While a century ago that proposition was widely acknowledged in higher education, it is now clearly not the standard position. One scholar at Harvard recently asserted “that the primary goal of a Harvard education is the pursuit of truth through rational inquiry, and that religion has no place in that. . . . Reason and faith are not yin and yang,” he contended. “Faith is a phenomenon. Reason is what the university should be in the business of fostering.” [7]

This skeptical scholar’s disdain for faith is not shared by all university professors. Indeed, colleagues at his own university vigorously disagreed with his position. [8] However, his point of view is prevalent enough that we should carefully examine—and be prepared to explain—what, if any, relationship there is between rational inquiry and faith in the acquisition of knowledge.

In that regard, the phraseology of verse 118—that learning should be sought “by study and also by faith”—is capable of more than one interpretation. One is that study and faith are two separate means of acquiring two different kinds of knowledge. Study (or rational inquiry) may be the means by which secular knowledge is acquired. And faith may be the means by which we obtain knowledge of sacred things. In explaining LDS belief to a group of Harvard students last year, Elder Oaks observed that “we believe there are two dimensions of knowledge, material and spiritual. We seek knowledge in the material dimension by scientific inquiry and in the spiritual dimension by revelation.” [9]

There is something to this position—quite apart from the persuasive fact that it seems to be endorsed by one both as bright and as authoritative as Elder Oaks. It seems clear that there are different kinds of knowledge. As Elder Neal A. Maxwell once observed, not “all knowledge is . . . of equal significance. There is no democracy of facts! . . . Something might be factual, but not be important. For instance,” Elder Maxwell continued, “today I wear a dark blue suit. That is true, but it is unimportant. As, more and more, we brush against truth, we sense that it has a hierarchy of importance. Some truths are salvationally significant and others are not.” [10] Furthermore, as Elder Maxwell also accurately noted, “certain knowledge comes only by revelation and, therefore, is only ‘spiritually discerned.’” [11]

From statements such as these by Elder Oaks and Elder Maxwell, one might well conclude that study, or rational inquiry, is useful solely for acquiring knowledge of material things, while faith, or revelation, is exclusively limited to the acquisition of knowledge of spiritual things—a position not necessarily at odds with the standard position at most major universities today (though, you would find considerable doubt as to the existence of spiritual things among many in that group).

However, at the risk of seeming to swim upstream against Elder Oaks and Elder Maxwell—though I think from other statements by those two, they would not disagree with me [12]—I suggest that this dualistic interpretation is incomplete. In the first place, the distinction between material and spiritual knowledge is, I believe, somewhat tenuous, given that the Lord himself has declared that unto Him “all things . . . are spiritual.” [13] More importantly, I believe that instead of setting forth two completely separate ways of learning, the injunction to “seek learning, even by study and also by faith” is intended to indicate that the two are synergistic means of acquiring any important knowledge, regardless of what we might characterize as the material or spiritual nature of that knowledge.

That is, my belief is that faith enhances our ability to gain knowledge by study, and study increases our ability to learn by faith—and that this mutually reinforcing process can be the means of acquiring important knowledge of any kind.

Let me suggest, for example, that faith can be—if not, must be—the initial impetus for all productive study. Faith in a perfect God whose word does not fail and who created worlds governed by eternal laws that do not change [14] gives us an assurance (to use the Joseph Smith Translation term for faith found in Hebrews 11:1) that the often difficult, and sometimes tedious and frustrating, work of acquiring knowledge by study is an endeavor worth pursuing because there are answers out there. If we were truly bereft of any belief that there are ultimate answers to our questions, we would be very unlikely to engage in any deep, meaningful search for the answers. Faith in God can provide the hope, and—in its more advanced stages, even the certainty—that we are seeking for something that can be found. Indeed, if we believe, as Joseph Smith taught, that “faith . . . is the moving cause of all action . . . ; that without it both mind and body would be in a state of inactivity, and all their exertions would cease, both physical and mental” [15]—if we believe that, then we would necessarily conclude that all study is precipitated by at least a small measure of faith in something. Thus, faith in God can be an impetus for the pursuit of knowledge through study, even when that study is based primarily on rational inquiry.

Furthermore, revelation, which is facilitated by faith in Christ, can greatly advance rational inquiry at other stages of the study process, as well. In the same talk in which he noted the difference between material and spiritual truths, Elder Oaks observed that “revelation also occurs when a scientist, an inventor, an artist or great leader receives flashes of enlightenment from a loving God for the benefit of His children.” [16] I suspect that many of you have had the experience of being stuck on a problem for hours or days, or even weeks or months, and then having the solution come to you in a flash. I certainly have. And, I can best account for those sudden insights by reference to Joseph Smith’s description of the revelatory process in which he says, “you feel pure intelligence flowing into you, [giving] you sudden strokes of ideas.” [17] Such revelatory experiences, which can advance our study of all things, are greatly enhanced, as Joseph taught, by the exercise and enhancement of our faith in Jesus Christ. [18]

Elder Dallin H. Oaks said, "The acquisition of knowledge is a sacred activity." © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Elder Dallin H. Oaks said, "The acquisition of knowledge is a sacred activity." © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

So as not to be misunderstood, let me make clear that I am not saying that one has to believe in Christ in order to have the kind of revelatory experiences that enhance one’s productive study of important matters. The Holy Ghost, which has the power—and responsibility—to reveal “the truth of all things,” [19] can come to anyone temporarily to enlarge their capacities in that way. However, I firmly believe that we can increase the frequency of those revelatory experiences if we develop our faith in Christ.

Just as faith, and its fruit of revelation, can enhance our ability to acquire knowledge by study, study is often a prerequisite for the revelatory experience that often characterizes learning by faith. As President Spencer W. Kimball once observed: “Perspiration must [usually] precede inspiration; there must be effort before there is excellence. We must do more than pray for these outcomes. . . . We must take thought. We must make effort. . . . We must be professional.” [20] Elder Oaks explained that “revelation in a particular discipline or skill is most likely to come to one who has paid the price of learning all that has previously been revealed [on that subject];” [21] that, in turn, requires a great deal of study, as you are all aware.

The Lord taught this lesson to Oliver Cowdery when Oliver attempted to translate the Book of Mormon. “Behold, you have not understood,” the Lord said. “You have supposed that I would give it unto you, when you took no thought save it was to ask me. But, behold, I say unto you, that you must study it out in your mind; then you must ask me if it be right, and if it is right I will cause that your bosom shall burn within you.” [22] Thus, it is clear that at least in some, if not most—or all—situations, study can facilitate the kind of learning by faith that is characterized by revelation.

That there is a kind of synergistic relationship between study and faith in acquiring knowledge is suggested by Alma’s famous exposition on the word in chapter 32 of Alma. In that discourse, Alma tells the Zoramites that they can know the truthfulness of his words if they will engage in “an experiment.” [23] Experimentation is the hallmark of rational inquiry or the scientific method, [24] the idea being that the ability of others to replicate what one has done provides an indication of the truthfulness of the principles discovered because one can, with confidence, predict the results that certain actions will produce. Thus, by calling on the Zoramites to “experiment upon [his] words,” Alma seems to be asking them to engage in an exercise of rational inquiry. [25] This was a logical starting point for Alma’s teaching of this people because, as we learn in the prior chapter, the Zoramites, like many modern scholars impressed by their own accomplishments, were so full of pride [26] that they had convinced themselves that “belief in Christ” was a “foolish tradition” to be set aside when important matters were considered. [27]

Even though Alma called upon the Zoramites to engage in a rational experiment in order to test the truthfulness of his teachings, he indicates that the experiment must begin with a least a modicum of faith. Those who wish to honestly engage in the experiment must, at a bare minimum, “desire to believe,” he says. [28] If they will do that much—if they will, in a sense, believe that they can find an answer to the question—Alma promises them that the predictable results of the experiment will occur: the word will begin “to enlarge” their souls; it will begin “to enlighten” their “understanding,” and it will begin “to be delicious” to them. [29] Thus, a rational experiment on the word, which is initiated by a bit of faith, produces predictable results, much like any other experiment of a scientific or rational nature. That in turn, Alma notes, will increase, or “strengthen,” the faith of those who honestly engage in the experiment, [30] with the ultimate result that they will have a perfect knowledge that the word is good, [31] or true.

Alma thus seems to describe an iterative—and synergistic—process in which faith first prompts rational inquiry. If the concept being tested is true, the inquiry will produce predictable results. The predictable results, in turn, produce increased faith, which, in its own turn, produces even greater insights—and ultimately perfect knowledge.

Note that this kind of synergistic acquisition of knowledge requires much more than mental exertion, and it correspondingly has an impact on much more than just the brain. The experimenters’ understanding is enlightened, as one might expect when knowledge is acquired by study or rational thought. But, in addition, their souls—their bodies and their spirits [32]—are enlarged. Thus, learning that involves both study and faith requires engagement of all our capacities. As Elder David A. Bednar has indicated, such learning “requires spiritual, mental, and physical exertion.” [33] With that understanding, one can see why Alma initiated his call for experimentation to the Zoramites with the admonition that they “awake and arouse [their] faculties.” [34] Acquisition of knowledge by study and also by faith is a holistic experience that requires one’s “heart, might, mind and strength.” [35]

What are the practical implications of the view that the acquisition of knowledge is enhanced when it is pursued by study and faith together, and that such an endeavor involves all of our faculties, not just our minds? There are many, but let me highlight just two.

Daily scripture study and prayer will enliven our faculties and prepare us to engage in the mind- and soul-stretching enterprise of acquiring knowledge. Matt Reier, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Daily scripture study and prayer will enliven our faculties and prepare us to engage in the mind- and soul-stretching enterprise of acquiring knowledge. Matt Reier, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

First, proper care of our physical bodies may enhance our ability to acquire knowledge by enabling us to better engage in both the mental work of study and the spiritual work of faith or revelation. That the care of our physical bodies aids the acquisition of knowledge by study is pointed out in verse 124 of the 88th section: “Retire to thy bed early, that ye may not be weary; arise early that your . . . minds may be invigorated.” [36] I sense this is not a common practice among college students—at least not if the lives of my college-aged children are any indication. However, the scripture makes clear that proper rest for the body can enhance the mental faculties that are necessary to acquire learning by study.

Care of our bodies may also enhance our ability to acquire knowledge by faith or revelation, as evidenced by the succeeding section of the Doctrine and Covenants, which contains the law of health commonly known as the Word of Wisdom. Sandwiched in between the more often highlighted promises of physical health that adherence to this commandment brings is the promise that those who comply “shall find wisdom and great treasures of knowledge, even hidden treasures.” [37]

I am not suggesting that you can acquire knowledge in the highest sense only if you are an Olympic athlete. However, I do believe that our ability to learn both by study and by faith will be enhanced if we keep our bodies as healthy as possible by getting enough sleep, eating healthy food, and engaging in regular physical exercise of some kind.

Second—and in a similar vein—the theory that learning is an integrated, holistic enterprise suggests that regular spiritual exercise will also enhance our ability to acquire knowledge because it will increase our ability to receive the kind of inspiration that characterizes learning by faith. Daily scripture study and daily prayer will enliven all our faculties (to use Alma’s term) and will therefore better prepare us to engage in the mind- and soul-stretching enterprise of acquiring knowledge by study and faith.

Along those lines, I urge you to take time to ponder the things you are studying on a regular basis. You will find that your ability to learn through study and faith will be greatly enhanced. As President Henry B. Eyring noted: “We read words and we may get ideas. We study and we may discover patterns and connections. . . . But when we ponder, we invite revelation.” [38] If my view is correct that optimum learning requires both study and revelation, we would all do well to detach ourselves from our computers, iPods, televisions, and telephones from time to time and quietly contemplate the issues before us.

In addition to shedding light on the way in which learning can be enhanced by both study and faith, section 88 contains another insight into the way in which we can improve our ability to engage in the sacred activity of acquiring knowledge. In verse 67, we read “And if your eye be single to my glory, your whole bodies shall be filled with light, and there shall be no darkness in you; and that body which is filled with light comprehendeth all things.” [39] Elder Oaks has called this “the most significant promise ever given pertaining to education.” [40] Imagine being able to comprehend all things—a handy skill to have during finals or comprehensive examinations; more importantly, an essential capacity for those who wish to be gods in the eternities. And that is what is promised us if our eye is single to God’s glory.

Given that magnificent promise, we might profitably ask ourselves what it means to have one’s eye single to God’s glory as one engages in the sacred activity of acquiring knowledge. I am sure I don’t understand the full implications of that important precondition, but the scripture clearly indicates that our motives are critical to our ability to understand all things. If our motivation for acquiring knowledge is to bring praise and glory to ourselves—the driving factor for many scholars—we will not meet the condition and therefore will not merit the promised reward.

With that in mind, we can appreciate more fully Elder Maxwell’s observation about academic motivation when he spoke at President Oaks’s inauguration in 1971: “Brigham Young University seeks to improve and to ‘sanctify’ itself for the sake of others,” he said; “not for the praise of the world, but to serve the world better.” [41] As much energy to learn as the desire for self-promotion can generate—and believe me, in the world of academics that desire can produce a lot of energy—it will not produce as much as will a sincere motivation to help others, to make life better for them, and ultimately to aid them in their quest for eternal life, which is God’s work and glory. [42]

The issue may therefore come down to whether our quest for knowledge is motivated by pride or by charity, which—though we don’t often think of them that way—are really polar opposites. In his classic talk on pride, President Ezra Taft Benson noted that the essence of pride is “enmity—enmity toward God and enmity toward our fellowman.” [43] As President Benson indicated, pride ultimately puts us at odds with our fellow men because it measures success by comparing us with others. In the words of C. S. Lewis, a portion of which President Benson quoted: “Pride gets no pleasure out of having something, only out of having more of it than the next man. We say that people are proud of being rich, or clever . . . , but they are not. They are proud of being richer, or cleverer . . . than others. If everyone else became equally rich or clever . . ., there would be nothing to be proud about. It is the comparison that makes you proud: the pleasure of being above the rest.” [44]

If the essence of pride is enmity, or hatred toward our fellow men, the antidote to pride would seem to be charity, or perfect love for our fellow beings. And if competition is the main manifestation of prideful enmity in an academic setting, cooperation would seem to be the main manifestation of charity.

Returning then to the promise in 88:67, this all suggests that we will learn better—and come closer to the promised day in which we will comprehend all things—if we are motivated by a desire to help our fellow beings than if our primary goal is to make sure we finish ahead of them. Let me illustrate this with a simple example.

As many of you know, law school can be very competitive. At most law schools, including BYU’s, students are literally ranked in order by their grades, and employers often make hiring decisions based primarily on that ranking. It is an environment rife with competition—and, therefore, a breeding ground for pride. On one occasion I led a classroom discussion on pride and competition. In that setting a first-year student, who had recently been through the soul-trying experience of the first set of law school finals, related the following experience, which I share with his permission:

When I came to BYU Law School, [he said] I immediately developed a big, fat crush on my entire 1L class: they were the nicest, smartest, most interesting people that I had ever been around. . . . [Even though] I realized right away that I was outgunned, outsmarted, and outpaced in every class. . . . I didn’t resent the successes of my peers; they were . . . my friends, and I liked them. . . .

As classes ended [however] and our 1L class threw all its weight, collectively and individually . . . towards finals, I was anxious. The anxiety grew and turned black. I studied hard and long, but I felt more insecure, the more I studied.

The student went on to say that he began to stay away from his classmates because each interaction with them convinced him more and more that they knew more he did, and he, therefore, knew nothing—and was destined to fail.

He then related:

I was praying early one morning about finals, asking for help to do my best [or even to just pass], and I began describing the bleak feelings I harbored, and I asked for help. After a few minutes, I [suddenly] found myself [praying] not [just] for myself but for my classmates, and not just for those few that I knew . . . struggled [with the material] as I did, but for the gifted and the talented as well. I prayed that they would do their best, that they would have peace and clarity. As I prayed for them, . . . I felt a surge of love for the classmates I had admired and had liked so much in the beginning.

He then began to reengage with the other students, not just to learn from them, but with the thought that he might actually have something he could offer some of them. At that point, his learning increased considerably. I don’t know exactly where this student finished in his class. And in the end, it doesn’t matter. I’m sure, however, that he did better on his exams once he began to focus on helping others rather than just on helping himself. I am even more certain that his eye was a bit more focused on God’s glory, rather than his own, and that he, therefore, came closer to comprehending all things.

Having considered ways in which we can increase our ability to engage in the sacred activity of acquiring knowledge, let me now turn to the second question: how can that enhanced ability help you with some of the decisions you face at this stage of your lives? For many of you the most pressing question in that regard is “What should I do with all this knowledge I have gained?” While the answer to that will vary with each individual, a general principle that may help each of you discover your unique answer is found in another set of familiar verses in section 88. Verses 78 and 79 provide a fairly comprehensive list of things concerning which we are to “be instructed.” I suspect most of you are familiar with the list, which covers just about every major discipline at a university. “Things both in heaven and in the earth, and under the earth; things which have been, things which are, things which must shortly come to pass; things which are at home, things which are abroad; the wars and the perplexities of the nations, . . . and a knowledge also of countries and of kingdoms.” [45]

However, many are less familiar with the succeeding verse, which indicates the purpose for which we should be acquiring all that knowledge: “That ye may be prepared in all things when I shall send you again to magnify the calling whereunto I have called you, and the mission with which I have commissioned you.” [46] It seems clear from the context in which the revelation was given that the Lord was referring in that instance to the more typical proselyting missions to which those who were being addressed had been called. However, I believe that verse 80 describes a principle that has broader application.

Each of you has been given gifts pertaining to learning; if not, you wouldn’t be here. Each of you has also been given the opportunity to spend considerable time and effort being “instructed” in “theory” and “principle” concerning your chosen discipline. I believe each of you has been blessed with those gifts and opportunities in order to do some specific things to advance the kingdom of God. In that sense, each of you has a “calling” which you should magnify.

The question is, of course, how do you know what that calling is? I suggest that one of the most profitable ways of finding that answer is to use the very knowledge-acquisition skills we have been considering—that you work to discover your individual answer to that question by study and also by faith and by keeping your eye single to the glory of God—with faith that there is an answer.

Let me provide an example of how this process can work. When the BYU Law School was announced in 1971, many wondered if it would succeed. It was a new enterprise that many doubted could work. It was clear to almost all that one of the key factors would be the quality of the initial faculty. The two principal employees of the law school at the time were Rex E. Lee, future president of BYU, and Bruce C. Hafen, future General Authority. Rex was the dean; Bruce, the associate dean. The two of them quickly set out in a quest to hire the new faculty. After almost a year on the job, and just a little more than a year before the school was scheduled to open, they had made no headway in that regard. Elder Hafen recalls that when he made his pitch to the handful of active LDS law professors in the country, the first question was always, “Well, who do you have so far?” His standard and somewhat hopeful response was, “If you come, there will be you, me, and Rex.” That apparently wasn’t very persuasive. Thus, Elder Hafen reports, the second question was always, “What is Carl doing?”

Carl was Carl Hawkins, who was a professor at the University of Michigan Law School, one of the best law schools in the county. A BYU undergraduate, he had finished at the top of his class at Northwestern Law School and then became one of the first, if not the first, LDS law graduate to clerk for a US Supreme Court justice, clerking for Chief Justice Fred Vinson in 1952–53. Following a relatively short but very distinguished career in private practice in Washington, DC, Carl joined the faculty at Michigan. By the time 1971 rolled around, he was one of the leading Torts professors in the nation, author of two leading texts on that subject, as well as of a multivolume treatise on Michigan Civil Procedure. He was among the brightest people I have ever met and the best I have ever encountered at using the Socratic method to help a class work its way through deep, difficult problems. In the world of legal education at the time, he was the Jimmer Fredette of his day—known by all as both a world-class scholar and a devout Mormon.

Over time, it became clear to the future President Lee and the future Elder Hafen that the success of their entire endeavor might well depend on convincing Carl Hawkins to come to BYU. However, repeated entreaties, including at least two personal visits to Ann Arbor, were unsuccessful. Carl was a stake president in Ann Arbor at the time, and he felt he could do more for the Church in that calling and in his prominent position at a top-flight law school than he could by coming to Provo to join an new and unproven enterprise.

Realizing what a difference it would make to have Carl on board, Dean Lee sought the help of President Marion G. Romney, a counselor in the First Presidency, who was the prime mover behind the establishment of the Law School. As Elder Hafen recalls it: “In an act of desperation, Rex recommended to President Romney that the First Presidency call Carl on a mission to the Law School. President Romney said, ‘We don’t do things that way.’ Ever the creative advocate, Rex said, ‘But President Romney, remember when Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery received the Aaronic Priesthood, and Joseph had to baptize Oliver before Oliver had baptized him? Sometimes when we’re just starting out, we have to do things a little differently.’ But it was no use.” [Elder Hafen recalled.] “We could do nothing but pray.” [47]

The next part of the story is legendary among the early graduates of the BYU Law School—and I hope it continues to be part of the lore of all BYU Law School graduates. As Elder Hafen explained it: “One day Rex and I were in President Oaks’ office with BYU’s academic vice president Robert Thomas. President Oaks’ secretary called to say that Carl Hawkins was on the line. Dallin took the call and talked softly with Carl out of our hearing. When he hung up, he looked out the window of his office at Mount Timpanogos, and I saw tears in his eyes. Then [President Oaks] smiled and said to us, “The Lord must really want this Law School. And He wants it to be a good one. Carl is coming!” We whooped and hollered as if Lancelot were coming to Camelot.” [Elder Hafen explained.] “From then on, the other positive dominoes fell into place. . . . Carl became our . . . expert witness, attesting to all comers that this law school met the highest standards of professional quality.” [48]

As I said, that story is well known among those familiar with the history of the BYU Law School and its subsequent meteoric rise in the world of legal education. What is less well known—in fact probably completely unknown outside the Hawkins family until a few years ago when Elder Hafen spoke on the subject at a Law School gathering—was Carl Hawkins’s side of the story. And it is that part of the story that illustrates the point I wish to make. Again, to quote Elder Hafen:

Some people have attributed Carl Hawkins’ decision [to come to BYU] to the formidable persuasive powers of Dallin Oaks and Rex Lee, and it is true that their presence at BYU was a positive factor for him. But Carl is a very private person who doesn’t say much about his most personal feelings. Only years later did he tell me the real reason why he came. . . .

[Carl] knew his decision was pivotal for other people, but he honestly felt he should stay at Michigan. He “could not [in his own words] imagine a more satisfactory professional position” than the one he held. An unusually rational and orderly thinker, he made a list of the reasons for staying and for leaving. He talked with friends and family. But as the practical deadline drew near, he decided to fast and pray. The day he chose to fast turned out to be an exasperating day at school, leaving him no time for personal reflection. So he went to his evening stake presidency meeting, where he planned to discuss his question with his counselors. But pressing stake business took more than their available time. Finally Carl arrived home after his wife, Nelma, was asleep. He was tired—and frustrated that his desire for prayerful meditation that day had gone unfulfilled. . . .

Nonetheless, as he began praying in his bedroom, he reviewed his list of factors for and against going to BYU. Carl later wrote in his personal history:

“As I reviewed the list, I drifted into a state that I cannot adequately describe, involving something more than cognitive processes or rational evaluation. Each consideration was attended by a composite of feelings that could not be expressed in words but still communicated something more true and more sure than rational thought. Every consideration that I had listed in favor of going to BYU was validated by a calm, overwhelming sense of assurance. Each consideration I had listed for not going to BYU was diminished to the point where it no longer mattered.

“[For example,] I had been deeply concerned whether my valued colleagues at Michigan would be able to understand my reasons for leaving. Now that concern melted away or evaporated into the night mists. . . .If some did not [understand], that would be their problem, and it would not diminish me. I fell asleep, content that I had finally made the right decision.”

Soon afterward Carl made that phone call to President Oaks. [49]

Carl Hawkins had spent most of his adult life being “instructed more perfectly in theory, in principle, in doctrine,” [50] learning of “things which have been, things which are; . . . things which are at home, things which are abroad.” [51] Why? So that he might “be prepared in all things . . . to magnify the calling whereunto [he was called].” [52] But that calling was not a formal invitation to serve from a Church leader. It came directly from God, as Carl Hawkins sought learning by study and by faith, and as he was motivated by concern for others, rather than the by the praise of the world.

I am not suggesting that your highest calling will be to teach at BYU—though for some of you that may be the case. What I am suggesting, though, is that the optimum means of acquiring the knowledge about academic matters also offers the best way of helping you make important decisions about other matters, including the kind many of you are currently facing. Each of you will have unique opportunities in your life—opportunities to do things no one else can do as well as you can. If you seek to understand what those are—by study and by faith—with an eye single to God’s glory—the time will come in which you will be filled with light and you will comprehend what God is calling you to do at that particular time.

In conclusion, let me share with you my personal conviction that the acquisition of knowledge can be a sacred activity. If pursued by study and by faith, if done with an eye single to God’s glory, it can be holy, and it can make us holy.

Notes

[1] Dallin H. Oaks, “A House of Faith,” in Educating Zion, ed. John W. Welch and Don E. Norton (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 1996), 119.

[2] See Lisa Miller, “Harvard’s Crisis of Faith,” Newsweek, February 11, 2010, available at http://

[3] Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Brigham Young (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1997), 194.

[4] D&C 131:6.

[5] History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1978), 4:588.

[6] Oaks, “A House of Faith,” in Educating Zion, 119.

[7] Steven Pinker, as cited in Miller, “Harvard’s Crisis of Faith.”

[8] “‘My colleagues fear that taking religion seriously would undermine everything a great university stands for,’ the Rev. Peter Gomes, Harvard’s chaplain and a professor of Christian history, told me. I think that’s ungrounded.” Cited in Miller, “Harvard’s Crisis of Faith.”

[9] Dallin H. Oaks, “Fundamental Premises of Our Faith” (address given to the faculty and students of Harvard Law School on February 26, 2010), available at http://

[10] Neal A. Maxwell, “The Inexhaustible Gospel,” Ensign, April 1993, 68.

[11] Maxwell, “The Inexhaustible Gospel,” 68 (quoting 1 Corinthians 2:14–16).

[12] In the same talk at Harvard, Elder Oaks noted that revelation can enhance learning by study. See text at note 16, infra. Similarly, Elder Maxwell once observed, “The Lord sees no conflict between faith and learning in a broad curriculum. . . . The scriptures see faith and learning as mutually facilitating, not separate processes.” Neal A. Maxwell, “The Disciple-Scholar,” in On Being a Disciple-Scholar, ed. Henry B. Eyring (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft,1995) 3, as quoted in John W. Welch, “The Power of Evidence in Nurturing Faith,” http://

[13] D&C 29:34.

[14] See D&C 88:13, 21–26, 34–38.

[15] Lectures on Faith, lecture 1, paragraph 10, accessible at http://

[16] Oaks, “Fundamental Premises of Our Faith.”

[17] Teaching of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2007), 132.

[18] “We believe that we have a right to revelations . . . and light and intelligence, through the gift of the Holy Ghost . . . if it so be that we keep his commandments, so as to render ourselves worthy in his sight.” Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith, 132.

[19] Moroni 10:5.

[20] Spencer W. Kimball, “Second-Century Address,” in Educating Zion, 72.

[21] Oaks, “A House of Faith,” 126.

[22] D&C 9:7–8; emphasis added.

[23] Alma 32:27.

[24] The Oxford English Dictionary defines the scientific method as “a method of procedure . . . consisting in systematic observation, measurement, and experiment, and the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses.”

[25] Alma 32:27.

[26] Alma observed that the hearts of the Zoramites “were lifted up unto great boasting, in their pride” (Alma 31:25).

[27] Alma 31:17.

[28] Alma 32:27.

[29] Alma 32:28.

[30] Alma 32:30.

[31] See Alma 32:33–35.

[32] See D&C 88:15.

[33] David A. Bednar, “Seek Learning by Faith,” Religious Educator 7, no. 3 (2006): 5.

[34] Alma 32:27.

[35] D&C 4:2.

[36] D&C 88:124.

[37] D&C 89:19.

[38] Henry B. Eyring, “Serve with the Spirit,” Ensign, November 2010, 60.

[39] D&C 88:67.

[40] Oaks, “A House of Faith,” 117.

[41] Neal A. Maxwell, quoted in Kimball, “Second-Century Address,” 66.

[42] See Moses 1:39.

[43] Ezra Taft Benson, “Beware of Pride,” Ensign, May 1989, 4.

[44] C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: Macmillan, 1952), 95.

[45] D&C 88:79.

[46] D&C 88:80; emphasis added.

[47] Bruce C. Hafen, “A Walk by Faith,” Clark Memorandum, Spring 2008, 24.

[48] Hafen, “A Walk by Faith,” 24 .

[49] Hafen, “A Walk by Faith,” 24; emphasis added.

[50] D&C 88:78.

[51] D&C 88:79.

[52] D&C 88:80.