Covenants, Sacraments, and Vows: The Active Pathway to Mercy

Peter B. Rawlins

Peter B. Rawlins, "Covenants, Sacraments, and Vows: The Active Pathway to Mercy," Religious Educator 13, no. 3 (2012): 205–219.

Peter B. Rawlins (joannrawlins50@msn.com) is the retired director of proselyting in the Missionary Department and at the Missionary Training Center in Provo, Utah.

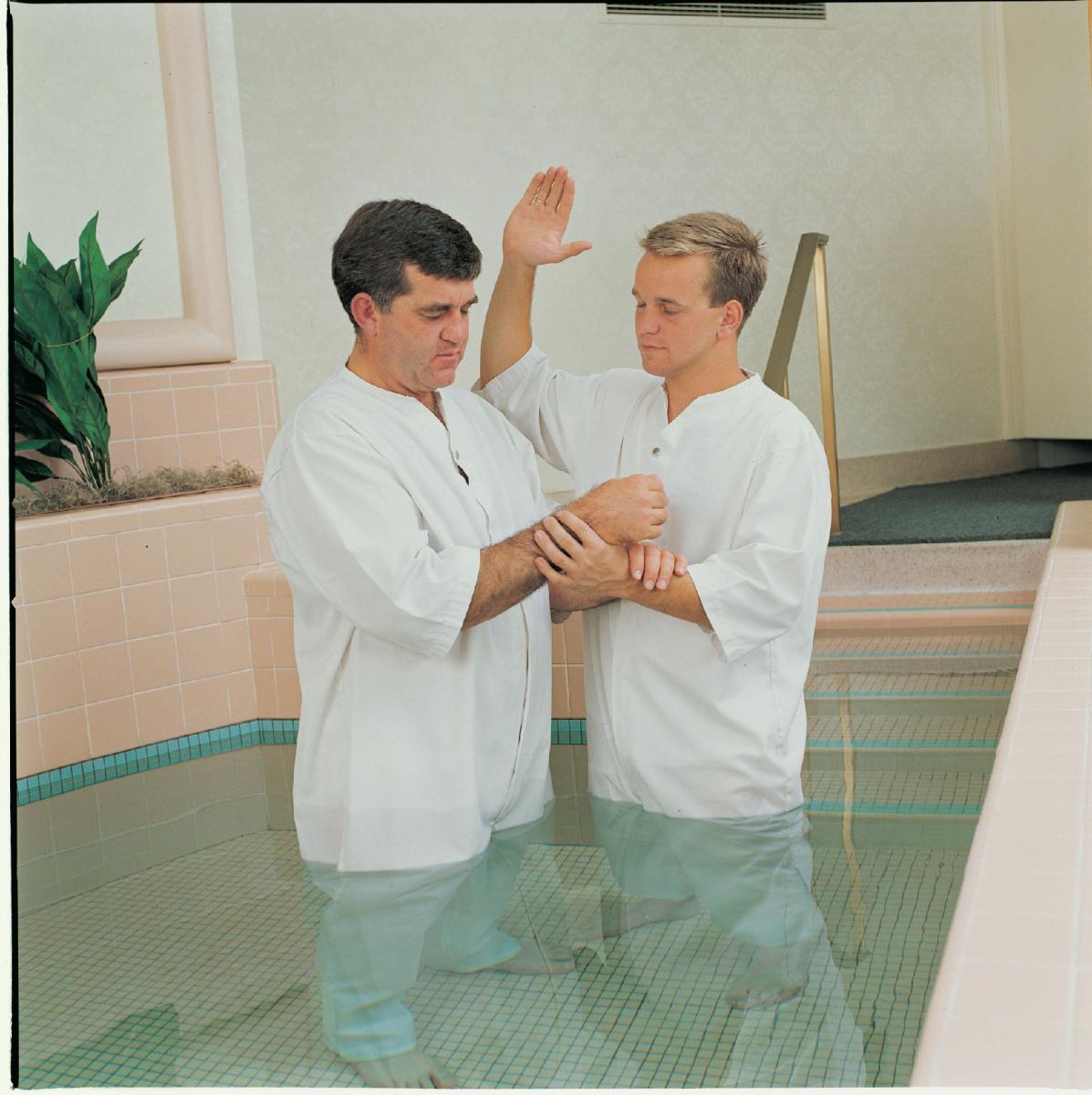

Baptism and confirmation are observable events where we make promises to always remember Christ, to keep his commandments, and to serve him to the end. Michael Schoenfeld, © 1984 Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Baptism and confirmation are observable events where we make promises to always remember Christ, to keep his commandments, and to serve him to the end. Michael Schoenfeld, © 1984 Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Every gospel teacher is delighted when a student actually applies some principle from the teacher’s lesson. These are the paydays. In a doctrinal framework, application represents “faith unto repentance,” which activates the plan of mercy in our lives (Alma 34:15–17; see also 42:22–24). Yet application, change, repentance are not always obvious. Change may happen in the privacy of the soul; it may happen days, weeks, even years after the lesson. Students may, like the Lamanites, be baptized with fire and the Holy Ghost and not know it themselves (see 3 Nephi 9:20). These changes may be the deepest, most important, and longest lasting, and the teacher may never know it. That is because while teachers may “be the means of bringing salvation” to their students (see 3 Nephi 18:32)—and there is much they can do—the conversion process is ultimately in the hands of the Lord, and we participate according to his will. We must have faith in the Lord’s unfolding purposes and timing.

When my wife and I were serving as proselyting missionaries, the zone leaders asked us to teach a less-active couple. The husband’s first marriage was a temple marriage, but it ended in divorce. He had not attended church for over seventeen years. His second wife was converted shortly after their marriage but had never attended church even once. Their response to our first two lessons was lackluster. During our third visit, however, the couple listened intently as we discussed the plan of salvation. At the end of the lesson, the father said simply, “This family needs to make some changes.” He did not tell us what he meant, but he was very determined. Two weeks later, we learned what “changes” meant. They had quit drinking alcohol and smoking. They continued to grow and eventually were endowed and sealed in the temple.

Another less-active couple responded differently to our teaching. Both the husband and wife had been raised in active families but had quit going to church at about age sixteen. They were devoted to their Sunday recreation, and they had other habits that were contrary to the gospel. We followed the principles in Preach My Gospel, inviting them at every lesson to make and keep commitments. We taught doctrine, bore testimony, promised blessings, and followed up. Even though they readily made “commitments,” they never kept a single promise.

These two experiences represent the opposite ends of a spectrum. Some people change; others do not. Some people eagerly keep commitments, and they come to “know of the doctrine” (John 7:17). Some people keep some of their commitments out of a sense of duty or curiosity or experimentation. Sometimes their change of behavior results in testimony, but not always. Some people fulfill their commitments perfunctorily or sporadically; seldom are they blessed with testimony. Other people are simply were too busy, complacent, or distracted to keep their commitments. Sooner or later their progress stops. “Real intent” (see Moroni 10:4; 6:8; 7:6; 2 Nephi 31:13)—the genuine determination to act—is so critical in realizing the Lord’s promises.

Our experience on our mission convinced us that people must obey “from the heart that form of doctrine which was delivered” to them (Romans 6:17). It is true that challenges and invitations can and often do lead to action and even to conversion. But ultimately, behavior must flow from a changed heart. Such changes are an expression of faith, which is a principle of action. Faith, to be faith, must be “unto repentance” (Alma 34:15–17).

Speaking to missionaries in a worldwide satellite broadcast, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland said, “When you teach investigators to keep their commitments, you are teaching them to become covenant-keepers.” [1] Becoming “covenant-keepers” is, as Elder Holland said, “the most fundamental thing we can discuss in the gospel plan, because only covenant-makers and covenant-keepers can claim the ultimate blessings of the celestial kingdom. Yes, when we talk about covenant keeping, we are talking about the heart and soul of our purpose in mortality.” [2]

Indeed, when we receive ordinances “with full purpose of heart, acting no hypocrisy and no deception before God, but with real intent, repenting of [our] sins, witnessing unto the Father that [we] are willing to take upon [us] the name of Christ” (2 Nephi 31:13), we enter an active pathway of change—changed attitudes, desires, and behaviors, and ultimately a change of our very natures. We gradually receive the image of Christ in our countenances (see Alma 5:14).

Since application is the culmination of the Church Educational System teaching paradigm (readiness, participation, application) gospel teachers should teach, advocate, and promote the covenant-keeping process. We realize that various teaching skills and techniques can result in observable behavior, which may or may not be permanent. What really matters are the desires of the heart. There is no better way for lessons to sink deeply and permanently into the heart of a student than through sincere observance of the covenant process. Ultimately, only through faith in this process can students become spiritually independent and self-reliant. This article explores the seamless transition from covenants, to sacraments, to daily vows—a powerful sequence that leads to application, action, experience, and character.

Ordinances and Covenants

We perhaps think of our covenants as events, for they are associated with ordinances, rites, and ceremonies that take place at a specific time and place. The saving ordinances of the gospel have two components. According to Elder Bruce R. McConkie, the first is the “visible, public, and outward sign”—the ordinance itself. We rightfully celebrate these events with invitations, gatherings of family and friends, gifts, and food. We record these events in journals; some are recorded in the permanent records of the Church. These actions and events are observable.

The second part is “the invisible, private, and inward witness—immersion in the Spirit, the baptism of fire and the Holy Ghost.” [3] Covenant keeping can be described as a personal, private interaction between a person and the Spirit. Reception of the Holy Spirit is very personal and intimate. The “Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost” teaches us all things (John 14:26) line upon line, here a little and there a little. The Holy Ghost brings things to our remembrance (including our covenants), reproves us of sin, strengthens us in times of temptation, warns us of spiritual danger, and grants us peace of conscience as we obey and as we repent and are forgiven. As we respond to the Spirit’s nudges, we gradually repent and take upon ourselves the image of Christ.

Covenant keeping is a process that happens over time and in a place poetically called the heart, which is “a symbol of the mind and will of man and the figurative source of all emotions and feelings.” [4] Concerning the covenant that the Lord would make with Israel in the last days, he told Jeremiah, “I will put my law in their inward parts, and write it in their hearts” (Jeremiah 31:33). The covenant is a law “written not with ink, but with the Spirit of the living God; not in tables of stone, but in fleshy tables of the heart” (2 Corinthians 3:3). Covenants are a personal, heartfelt striving for perfection. The covenant-making process supports and enhances our natural impulses for personal improvement. Ordinances are a visible sign, a “witness before [God] that ye have entered into a covenant” (Mosiah 18:10).

Ordinances apply particularly at the critical point when our minds and hearts commit to act out our beliefs. A covenant is a promise, made in the most sacred circumstances, to act as though unseen things are true. The ordinances foster the growth of faith by providing a context in which we covenant to translate assurance into action. We determine to patiently act on gospel principles, knowing that our faith will be tried before we receive the promised reward (see Ether 12:6). Ordinances and the accompanying covenants cause us to allocate our choices about time. As we fulfill our covenants by sacrifice, we then receive the promised spiritual power.

Our covenants should be watershed events in our lives. They are a Great Divide, with the natural man on one side and the man of Christ on the other. Enabling power, or grace, is the blessing promised for keeping covenants. Baptism, the sacrament, and prayer form a succession of spiritual renewals that lead to works, to action, and to mature faith. They facilitate ongoing and sincere repentance.

Baptism

Baptism is “a witness and a testimony before God, and unto the people, that they had repented and received a remission of their sins” (3 Nephi 7:25). Baptism is an affirmation of both our intentions and our accomplishments. This visible sign assures both heavenly and mortal witnesses that we have repented of past misdeeds and that we are determined to sin no more. The full title for the ordinance of baptism is “baptism of repentance for the remission of sins, agreeable to the covenants and commandments” (D&C 107:20; see also Mark 1:4; Luke 3:3; Acts 13:24; 19:4). The baptism “of” repentance is an outward ordinance that signifies our inward intent. It is a baptism that originates with or is derived from a humble, contrite, repentant spirit. A repentant attitude is the cause, motive, or reason for baptism. “The first fruits of repentance is baptism” (Moroni 8:25). Repentance characterizes the kind of baptism we are to receive. We demonstrate before baptism that we have repented and have “received of the Spirit of Christ unto the remission of [our] sins” (D&C 20:37). We “bring forth...fruits meet for repentance” (Matthew 3:8). We bring our change of heart, attitude, and behavior to fulfillment, or fruition. Through baptism we demonstrate that our repentance is complete and permanent. We assure our worthiness for baptism through suitable or proper repentance. “They were not baptized save they brought forth fruit meet that they were worthy of it. Neither did they receive any unto baptism save they came forth with a broken heart and a contrite spirit, and witnessed unto the church that they truly repented of all their sins” (Moroni 6:1–2; see also Alma 13:13; 34:30).

A most interesting passage occurs in Alma: “Whosoever did not belong to the church who repented of their sins were baptized unto repentance, and were received into the church” (Alma 6:2). Those who repented were “baptized unto repentance” (see also Alma 5:62; 9:27; 49:30; Mosiah 26:22; Helaman 3:24; 5:17, 19; 3 Nephi 7:26; Moroni 8:11, 25). Is this redundant, a tautology, either deliberate or unintentional? Not so, unless repentance itself is redundant. Unto expresses or denotes motion directed toward and reaching a goal; for the purpose of; to result in, bring about, cause, or produce. Thus we not only exercise faith unto repentance before baptism, but we are baptized for the purpose of repentance. Baptism leads to or results in an ongoing change of thoughts, feelings, attitudes, and behaviors—continual striving to reach the high standard of obedience. Repentance forms the supporting pillars on either side of baptism. Without repentance, the covenant would collapse.

We are baptized once in our lifetimes, but the cleansing that comes from continuing obedience is a lifelong quest. “Baptism is a once-in-a-lifetime ordinance. We are baptized on one occasion only—for the remission of our sins, for entrance into the earthly church, and for future admission into the kingdom of heaven.” [5] Baptism and confirmation are observable events, during which we make general and universal promises to always remember Christ, to keep his commandments, and to serve him to the end. But we are mortals, with human failings, weaknesses, and imperfections. In the press of daily cares, we easily lapse into a certain forgetfulness of our promises—vows made long ago, often in childhood. And so we sin, in spite of our best intentions. “After baptism, all men sin. None obey the Lord’s law in perfection; none remain clean and spotless and fit for the association of Gods and angels.” [6] Knowing that we must gradually overcome our fallen natures, the Lord has provided the sacrament for regular renewal of our covenants; weekly renewal keeps them fresh and lively.

Sacrament

President Howard W. Hunter said that the plan of salvation and progression provides “a strong sense of purpose,” “reasons for action,” and “guides for action in the form of real goals and objectives.” The plan of mercy answers the question “why” we should act in harmony with God’s commandments. However, this “long-range—even an eternal—goal . . . must be broken up into short-range, immediate objectives that can be achieved today and tomorrow and the next day. The gospel imperatives constitute an immediate challenge to action in our lives right now, today, as well as a plan for action eternally.” He concludes that “gospel imperatives . . .are the active pathway to personal participation in the laws of the gospel.” [7] This is where the sacrament comes in.

“Partaking of the sacrament is not to be a mere passive experience.” [8] The sacrament continues the covenant-keeping process. The baptismal covenant is general, and it is the same for every person. The sacrament covenant is specific. It is concrete, but the specificity is individual and personal. It will be different for every person. It focuses on what we need to do this week, this day, even this moment to repent. It moves our covenants down the ladder of abstraction so that they take a concrete, definable form. It leads to a change of attitude and behavior. The sacrament is the ordinance of enduring to the end. It is a time for introspection, for self-examination—all in the context of remembering the Savior’s sacrifice and promise of mercy. We “examine” ourselves (1 Corinthians 11:28; 2 Corinthians 13:5). Our baptismal covenant matures through partaking of the sacrament.

Central to this brief period of worship is a review of and recommitment to our covenants. Our purpose in doing so is to repent, which is the necessary condition for achieving our proximate goal of enjoying the gift of the Holy Ghost through the mercy of Christ. “Those of us who have been baptized will review our lives to see what we have done or not done that determines whether the Lord can keep his promise to let the Spirit always be with us. Because we are human still, that reflection usually leads to a desire to repent of things both done and not done.” [9]

The Lord had provided the sacrament for regular renewal of our covenants; weekly renewal keeps them fresh and lively. Marty Mayo, © 1986 Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

The Lord had provided the sacrament for regular renewal of our covenants; weekly renewal keeps them fresh and lively. Marty Mayo, © 1986 Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Elder M. Russell Ballard said: “A periodic review of the covenants we have made with the Lord will help us with our priorities and with balance in our lives. This review will help us see where we need to repent and change our lives to ensure that we are worthy of the promises that accompany our covenants and sacred ordinances. Working out our own salvation requires good planning and a deliberate, valiant effort.” [10]

Reviewing our covenants, examining ourselves, and assessing our spiritual status necessitate listening to the still, small voice of the Spirit. The whisperings will be subtle but distinct, and we had better respond. President Henry B. Eyring taught:

You will listen best when you feel, “Father, thy will, not mine, be done.” You will have a feeling of “I want what you want.” Then, the still small voice will seem as if it pierces you. It may make your bones to quake. More often it will make your heart burn within you, again softly, but with a burning which will lift and reassure.

You will act after you have listened because when you hear his voice by the Spirit you will always feel that you are impelled to do something. You mustn’t be surprised if the instruction seems accompanied with what you feel as a rebuke.

You might prefer that God simply tell you how well you are doing. But he loves you, wants you to be with him, and knows you must have a mighty change in your heart, through faith on the Lord Jesus Christ, humble repentance, and the making and keeping of sacred covenants. [11]

The Savior cautioned the early Saints to partake of the sacrament “with an eye single to my glory—remembering unto the Father my body which was laid down for you, and my blood which was shed for the remission of your sins” (D&C 27:2). The Lord then promised a grand future event: “Behold, this is wisdom in me; wherefore, marvel not, for the hour cometh that I will drink of the fruit of the vine with you on the earth” (D&C 27:5). This great sacrament meeting will include prophets of the past as well as “all those whom my Father hath given me out of the world” (D&C 27:14).

In this context, the Lord commands, “Wherefore, lift up your hearts and rejoice, and gird up your loins, and take upon you my whole armor, that ye may be able to withstand the evil day, having done all, that ye may be able to stand” (D&C 27:15). Putting on the whole armor of God, as described in the following verses (see D&C 27:16–18 and Ephesians 6:11–17), is intimately associated with partaking of the sacrament. It is another way of saying that we keep ourselves “unspotted from the world” (D&C 59:9).

To keep ourselves “unspotted from the world,” we go to the Lord’s house on the Sabbath and offer up our sacraments, vows, devotions, and oblations (see D&C 59:9–12). A sacrament is a person’s personal, private promise to God to fulfill one’s covenants to keep the commandments. It takes place in that secret chamber, the heart, a sanctuary known only to the person and the Spirit. It is a profound expression of faith in things that are unseen, but are true. A sacrament is “a pledge and promise on man’s part to forsake personal sins, knowing that if he does so he will be blessed by the Lord. When the saints partake of the ordinance of the sacrament, they promise not simply to keep the commandments in general, but also to serve and conform and obey where they as individuals have fallen short in the past. Every man’s sacraments are thus his own; he alone knows his failures and sins, and he alone must overcome the world and the flesh so that he can have fellowship with the saints.” [12]

A vow is a solemn promise made to God to perform some act, or make some gift or sacrifice; to dedicate, consecrate, or devote to some person or service. The first kind of vow was “dedication—some person or thing was given to the Lord.” Thus vows rectify sins of omission, and we promise to give consecrated service in the Lord’s kingdom. We may, for example, promise to participate in fulfilling the mission of the Church—talking to a nonmember neighbor, searching for an ancestor, alleviating physical suffering, or improving our home teaching. The second kind of vow was “abstinence—a promise made to abstain from some . . . act or enjoyment.” [13] Thus a vow corrects sins of commission. We may, for example, promise to be more honest, to control our desires for wealth, or to keep our thoughts pure.

Oblations are “offerings, whether of time, talents, or means, in service of God and fellowman” (D&C 59:12, footnote b). Anciently, oblations were animal sacrifices. Each Israelite was to “offer his oblation for all his vows” (Leviticus 22:18). The oblation was the visible, public surety that the person would keep his vows. These oblations would be “most holy” (Numbers 18:9). Today the offering of time, talents, or means in God’s service is the surety that we are keeping our vows. In a day of righteousness, we “shall do sacrifice and oblation; yea, [we] shall vow a vow unto the Lord, and perform it” (Isaiah 19:21).

Devotions involve the action of setting apart to a sacred use or purpose; solemn dedication, consecration. Offering up our devotions includes centering our attention or activities on the Lord; dedicating, consecrating, or hallowing our time and resources, setting them apart for a particular and higher use or end. The setting apart involves sacred space and time, separated from that which is profane and common.

These terms share a connected thread of thought: translating our beliefs into action; converting doctrine to duty; transforming teachings to tasks. By doing so, we chart a course to eternal life—one action at a time. To thus “speedily repent” (see D&C 109:21; 63:15; 136:35) is the essence of spiritual progression. With such frequent, continual, and conscientious repentance, we can see that “the sacrament of the Lord’s supper is an ordinance of salvation in which all the faithful must participate if they are to live and reign with him.” [14]

Active participation means far more than just partaking of bread and water. It means that we actually and in reality conform to the commandments. In doing so, “we receive a remission of our sins through baptism and through the sacrament. The Spirit will not dwell in an unclean tabernacle, and when men receive the Spirit, they become clean and pure and spotless.” [15]

A sacrament is a person's personal, private promise to God to fulfill one's covenants to keep the commandments. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

A sacrament is a person's personal, private promise to God to fulfill one's covenants to keep the commandments. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

One vital way that the Spirit helps us keep our covenants is by bringing “all things to [our] remembrance” (John 14:26), including our devotions, sacraments, and our vows. “By having the Holy Spirit as one’s prompter in the moments of temptation,...this law of the Gospel, so contrary to the natural disposition, may be complied with.” [16]

The sacrament is a pivotal moment. It points to the past—the covenants we made at baptism. And it points to the future—our specific plans for improvement during the days until we again partake of the table of the Lord’s supper.

Of course, if our participating in this or any ordinance is just an empty shell of outward conformity, the seed of faith will be barren. President David O. McKay warned that “the form of worship is frequently an outward compliance without the true soul acknowledgment of its deep spiritual significance.” He added, “In the partaking of the sacrament, there is danger of people’s permitting formality to supersede spirituality.” [17] We must act upon our vows. “The more often [one] feels without acting, the less [one] will be able ever to act, and, in the long run, the less [he or she] will be able to feel.” [18]

Prayer—Daily Vows

C. S. Lewis’s senior devil, Screwtape, laments when Wormwood’s (his understudy) patient is “making none of those confident resolutions which marked his original conversion. No more lavish promises of perpetual virtue...not even the expectation of an endowment of ‘grace’ for life, but only a hope for the daily and hourly pittance to meet the daily and hourly temptation!” [19] This is an astounding insight into human nature as well as the challenge of a religious conversion.

Wormwood’s patient, however, is lacking a huge asset—the covenant relationship with Christ established by the authority and power of the restored priesthood. This covenant relationship includes general, lifetime covenants to keep all of the commandments, to remember Christ always, and to serve him until the end. But this covenant, though general and long-term, should not be characterized as “lavish promises of perpetual virtue,” for it is intimately connected with the practicality of daily vows. And a person who is confirmed does indeed have the “expectation of an endowment of ‘grace’ for life”—the gift of the Holy Ghost and the enabling power of the Atonement.

With all of these covenant advantages, still we all need to have “a hope for the daily and hourly pittance to meet the daily and hourly temptation!” That is the nature of life. And the Lord in his wisdom has made provision. Flowing from the once-in-a-lifetime covenant of baptism is the weekly covenant of the sacrament. Flowing from the weekly covenant of the sacrament is prayer, the daily and hourly petition for strength to overcome temptation.

In the midst of introducing the sacrament among the Nephites, the Savior said, “Verily, verily, I say unto you, ye must watch and pray always, lest ye be tempted by the devil, and ye be led away captive by him” (3 Nephi 18:15).

In the midst of a revelation on Sabbath observance, the Lord said, “Nevertheless thy vows shall be offered up in righteousness on all days and at all times” (D&C 59:11). Commenting on this passage, Elder McConkie wrote, “True worship goes on seven days a week. Sacraments and vows and covenants of renewal ascend to heaven daily in personal prayer.” [20]

The Lord conveyed a sense of urgency to the Nephites because, he said, “Satan desireth to have you, that he may sift you as wheat” (3 Nephi 18:18; see also verses 14–19). The command to pray always for the purpose of overcoming temptation is repeated often in scripture (see Alma 34:17–19, 27; 37:36–37). If we do not offer up daily vows through sincere prayer, we may be “tempted above that which [we] can bear” (Alma 13:28). One reason for the apostasy of the Zoramites was their refusal to “observe the performances of the church, to continue in prayer and supplication to God daily, that they might not enter into temptation” (Alma 31:10).

James taught that “every man is tempted, when he is drawn away of his own lust, and enticed. Then when lust hath conceived, it bringeth forth sin: and sin, when it is finished, bringeth forth death” (James 1:14–15). Our temptations are our own; no one can force us to yield. We choose to do so. Likewise, when we deliberately choose to pray, to offer up our vows daily, we are protected from temptation on natural principles. When our hearts are “full, drawn out in prayer unto him continually for [our] welfare, and also for the welfare of those who are around [us]” (Alma 34:27), we will scarcely have room for temptation. Prayer will drive temptation from our hearts, replacing evil actors on the stage of our minds with noble and worthy actors. We will be able to “withstand every temptation of the devil, with [our] faith on the Lord Jesus Christ” (Alma 37:33).

Our daily vows are inseparably connected with searching and feasting on the scriptures. The scriptures contain the “fine print” of the covenant contract. The impressions of the Spirit that come as we ponder holy writ provide the substance of our vows on a very specific, personal basis. Thus the very common admonition in the congregations of the Church to study and pray daily. While “common” in the sense of frequent, this counsel is not “common” in the sense that it lacks special qualities.

This brings us to the conclusion, the completion, the end of our part of the covenant. We offer up our vows, sacraments, oaths, devotions, and oblations on all days and at all times. Otherwise, Satan may sift us as wheat. We may succumb to temptation. Satan may lead us with a flaxen cord until we become entangled in his strong cords forever (see 2 Nephi 26:22).

Our prayers, like our sacramental vows, should lead to action, repentance, and obedience. Prophets have taught this principle:

“Please notice the requirement to ask in faith, which I understand to mean the necessity to not only express but to do, the dual obligation to both plead and to perform, the requirement to communicate and to act....Meaningful prayer requires both holy communication and consecrated work....Prayer, as ‘a form of work,...is an appointed means for obtaining the highest of all blessings’ (Bible Dictionary, ‘Prayer,’ 753). We press forward and persevere in the consecrated work of prayer, after we say ‘amen,’ by acting upon the things we have expressed to Heavenly Father.” [21]

“Our deeds, in large measure, are children of our prayers. Having prayed, we act; our proper petitions have the effect of charting a righteous course of conduct for us.” [22]

“Sincere praying implies that when we ask for any blessing or virtue, we should work for the blessing and cultivate the virtue.” [23]

A very effective way of offering up our vows on all days and at all times is to express our intentions and plans for the day in our morning prayers. During the day, we continue to pray in our hearts for the ability to fulfill our plans. Then, in the evening, we report to the Lord what we have done. We hold ourselves accountable for our actions before the Lord—a foreshadowing and acknowledgment of that last great Judgment Day when we will stand before God to be judged according to our works and our desires. “Morning and evening prayers—and all of the prayers in between—are not unrelated, discrete events; rather, they are linked together each day and across days, weeks, months, and even years. This is in part how we fulfill the scriptural admonition to ‘pray always’ (Luke 21:36; 3 Nephi 18:15, 18; D&C 31:12).” [24]

When we are inspired to act, we must not delay nor forget. The Prophet Joseph Smith cautioned the Saints to keep notes of their important discussions and decisions: “For neglecting to write these things when God had revealed them, not esteeming them of sufficient worth, the Spirit may withdraw and God may be angry; and there is, or was, a vast knowledge, of infinite importance, which is now lost.” [25] This principle applies as well to our personal spiritual prods. We have been further counseled:

“Write down the tasks you would like to accomplish each day. Keep foremost in mind the sacred covenants you have made with the Lord as you write down your daily schedules.” [26]

“How many specific things go undone because forgetfulness covers what a pencil and paper could have made into a prickly reminder?” [27]

Our actions flow from consecrated prayer, which flows from self-examination during the sacrament, which in turn flows from our baptismal covenants. President Hunter said, “Whenever we tackle a gospel imperative, immediate goals will help us master it. . . .We should set up long-range and eternal goals, to be sure—they will be the guides and inspiration of a lifetime.” Baptismal covenants fit this description. They parallel what the world calls “values,” or high-level principles that govern our lives. President Hunter continued, “But we should not forget the countless little immediate objectives to be won tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow. To win and pass these objectives marks our progress toward the greater goals and ensures happiness and the feelings of success along the way.” [28] The sacrament parallels what the world calls “goals,” or medium-level actions. And offering up our vows in our daily prayers parallel what the world accomplishes through specific plans.

We are cautioned to “arise up and be more careful henceforth in observing your vows, which you have made and do make,” with the promise that we “shall be blessed with exceeding great blessings” (D&C 108:3). Students who link their classroom studies to this covenant process are more likely to change, to apply, to act, to repent and progress spiritually. Wise is the teacher who facilitates this connection. For salvation comes only “through the merits, and mercy, and grace of the Holy Messiah” (2 Nephi 2:8), and “the extension of mercy will not be automatic. It will be through covenant with Him. It will be on His terms, His generous terms.” [29]

This covenant-keeping process is a simple idea, much like teaching a child to keep his promises. Yet it is as difficult as we make it. The “simpleness of the way, or the easiness of it” (1 Nephi 17:41) is obvious. All that it demands is that we yield “to the enticings of the Holy Spirit,” put off “the natural man,” and become “as a child, submissive, meek, humble, patient, full of love” (Mosiah 3:19). But the simplicity of the way is also the difficulty of the way, for the natural man mightily resists its demise. The covenant-keeping process is a powerful antidote for the natural man. Resolve, determination, persistence, humility, patience, faith, and sacrifice are required to observe our covenants. “But blessed are they who have kept the covenant and observed the commandment, for they shall obtain mercy” (D&C 54:6).

Notes

[1] Jeffrey R. Holland, “Making and Keeping Covenants,” missionary satellite broadcast, April 25, 1997, 4.

[2] Holland, “Making and Keeping Covenants,” 1.

[3] Bruce R. McConkie, A New Witness for the Articles of Faith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1985), 241–42.

[4] Guide to the Scriptures, “Heart.”

[5] McConkie, New Witness, 293.

[6] McConkie, New Witness, 293.

[7] Howard W. Hunter, “Gospel Imperatives,” Improvement Era, June 1967, 101–3.

[8] Marion G. Romney, in Conference Report, April 1946, 39–40.

[9] Henry B. Eyring, “Making Covenants with God,” fireside address, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, September 8, 1996.

[10] M. Russell Ballard, “Keeping Life’s Demands in Balance,” Ensign, May 1987, 14.

[11] Henry B. Eyring, “To Draw Closer to God,” Ensign, May 1991, 67.

[12] McConkie, New Witness, 301–2.

[13] Bible Dictionary, “Vows,” 787.

[14] Bruce R. McConkie, The Promised Messiah (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1978), 384.

[15] McConkie, New Witness, 299.

[16] B. H. Roberts, The Gospel: An Exposition of Its First Principles and Man’s Relationship to Deity (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1966), 191–92.

[17] David O. McKay, Gospel Ideals (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1953), 71.

[18] C. S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters (New York: Macmillan, 1966), 61.

[19] Lewis, Screwtape Letters, 62.

[20] McConkie, New Witness, 302.

[21] David A. Bednar, “Ask in Faith,” Ensign, May 2008, 94–95.

[22] Bruce R. McConkie, “Why the Lord Ordained Prayer,” Ensign, January 1976, 12.

[23] David O. McKay, Secrets of a Happy Life, 114–15.

[24] David A. Bednar, “Pray Always,” Ensign, November 2008, 42.

[25] Joseph Smith, History of the Church, 2:199.

[26] Ballard, Life’s Demands, 14.

[27] Neal A. Maxwell, Deposition of a Disciple (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 33.

[28] Hunter, “Gospel Imperatives,” 103.

[29] Boyd K. Packer, “The Mediator,” Ensign, May 1977, 56.