“Serious Reflection” for Religious Educators

Ryan S. Gardner and Michael K. Freeman

Ryan S. Gardner and Michael K. Freeman, "'Serious Reflection' for Religious Educators," Religious Educator 12, no. 3 (2011): 59–81.

Ryan S. Gardner (gardnerrs@ldschurch.org) was an instructional designer/writer in Curriculum Services, Department of Seminaries and Institutes when this was written.

Michael K. Freeman (michael.freeman@usu.edu) was associate dean of Administrative Leadership at Utah State University when this was written.

Religious educators reflect on at least two fundamental questions that can have life-changing answers for themselves and their students: What should I teach? and How should I teach it? Christina Smith, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Religious educators reflect on at least two fundamental questions that can have life-changing answers for themselves and their students: What should I teach? and How should I teach it? Christina Smith, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

As a young man wrestling with religious questions that he knew would have serious ramifications for himself and his family, Joseph Smith reported that his mind was “called up to serious reflection and great uneasiness” (Joseph Smith—History 1:8). Struggling with challenging problems often causes mental, emotional, or even spiritual discomfort. However, the Prophet Joseph Smith learned that only by “serious reflection” could he come to a decision about what course of action he must pursue to find resolutions to the challenges of life (see Joseph Smith—History 1:9–13). Religious educators committed to teaching the restored gospel of Jesus Christ will also benefit from “serious reflection,” even though that reflection may, at times, lead to “great uneasiness.” As religious educators better understand and implement reflective practices and processes in a way that contributes to their sustained professional development, they will develop greater alignment between their ideals and their classroom behaviors. Such alignment will increase the positive impact of their classroom instruction.[1]

Professional Development in Religious Education

As seminary and institute teachers in the Church Educational System, we believe that we are “accountable to God for the effort and progress [we make] in [our] personal development.” This means that we “are responsible to learn [our] duties, act in [our] assignments in all diligence, improve upon [our] talents, and seek to gain other talents (see D&C 107:99; see also D&C 82:18).” This “development results from learning and applying gospel principles, acquiring desired skills, reflecting on current assignments, and trying new ideas.” [2] In addition to our covenant relationship with God to work on our personal development, “CES employees have a contractual obligation with the Church and with the Church Educational System . . . to develop professionally by becoming better teachers and leaders, by striving to meet the objective of religious education and fulfill their commission.”[3] Professional development for religious educators grows out of deep spiritual commitments,[4] personal integrity, and a desire to bless the lives of those they teach.

Educational researchers and scholars who have studied the role of administrators and supervisors in professional development have suggested the following: “The long-term goal of developmental supervision is teacher development toward a point at which teachers, facilitated by supervisors, can assume full responsibility for instructional improvement.”[5] While leaders can assist teachers in their professional development, teachers will be more consistent and effective when they take primary responsibility for their own professional development. Teachers who continue to grow and improve take seriously this commitment to professional development throughout the entire course of their career.[6]

Teacher Reflection in Religious Education

In the context of professional development, reflection may be thought of as “deliberate thinking about action with a view to its improvement.”[7] Though our questions may not be of the same magnitude as those the Prophet asked in the Sacred Grove, religious educators in the Church Educational System reflect on at least two fundamental questions every day that can have life-changing answers for themselves and their students: What should I teach? and How should I teach it? These seemingly simple questions contain several subqueries that make them more complicated than they might at first appear. A seminary teacher approaching a lesson on a specific chapter of scripture might wrestle with some of the following questions: What was the intent of the inspired author who wrote this scripture block? What are the needs and abilities of my students? What principle or doctrine is the Lord inspiring me through his Spirit to teach? This same teacher seeks simultaneous resolution to other questions that pertain to teaching methodology, or how to teach the lesson: How can I help my students be ready to understand and apply what they will learn from the scriptures? Will this approach lift my students spiritually? Will the approach I have chosen offend anyone? Does the method I have chosen match the level of sacredness of the doctrine or principle the students will learn? Do I need to vary my teaching methods to help students with different learning styles?[8]

Beyond these questions, thoughtful teachers may reflect on even more intricate questions concerning a variety of issues, such as classroom discipline[9] (How will I make sure that a student doesn’t disrupt the class, without alienating the student?), student participation (How can I help more students participate meaningfully, without minimizing the contribution of students who regularly participate?), and the impact they, the teachers, hope to have on their students (Are the truths I have chosen to teach and the methods I use to teach them going to strengthen my students’ testimonies of the restored gospel and help them be true disciples of Jesus Christ?). Conscientious seminary and institute teachers may also consider questions about whether or not the lessons they plan accomplish the S&I Objective according to the fundamentals of good teaching as outlined in the Teaching and Learning Emphasis (TLE). And these are just some of the challenges that gospel teachers might reflect on every day, whether or not they deliberately articulate these questions and the solutions they devise.

The Reflection Dilemma

Chris Argyris and Donald Schön, who have spent several decades studying and writing about reflective theory and practice in many professional contexts including education, have shown that reflection is a more challenging process than just sitting down and thinking about something we have learned or done.[10] They propose that there is usually a difference between a teacher’s “espoused theories,” which define a teacher’s ideals or beliefs, and his or her “theories in use,” which describe what a teacher actually does. They explained: “When someone is asked how he would behave under certain circumstances, the answer he usually gives is his espoused theory of action for that situation. . . . However, the theory that actually governs his actions is his theory-in-use, which may or may not be compatible with his espoused theory; furthermore, the individual may or may not be aware of the incompatibility of the two theories.”[11] They propose that successful reflection helps teachers identify incongruencies between espoused theories and theories in use to develop internal consistency that leads to “hybrid theories of practice.”[12]

However, in their research and training seminars and workshops, Argyris and Schön found that developing effective hybrid theories of practices was often difficult because “we try to compartmentalize—to keep our espoused theory in one place and our theory-in-use in another, never allowing them to meet. One goes on speaking in the language of one theory, acting in the language of another, and maintaining the illusion of congruence through systematic self-deception.”[13] All teachers, to some degree, face this inconsistency in their personal and professional lives. Well-known educator Herbert Kohl commented that his beliefs always “ran ahead” of his personal ability to teach according to them.[14] The Apostle Paul noted that in mortality we see ourselves only “through a glass, darkly,” and only at some future date will we “know even as also [we are] known” (1 Corinthians 13:12). Yet, we should all be striving for “greater consistency between our beliefs and our actions.”[15]

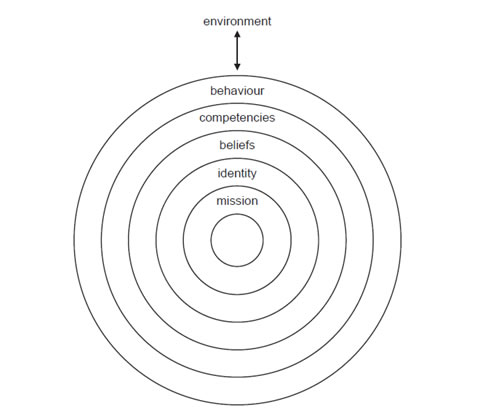

Fred Korthagen noted that while “there is considerable emphasis on promoting reflection in teachers . . . it is not always clear exactly what teachers are supposed to reflect on when wishing to become better teachers. What are important contents of reflection?”[16] Korthagen posited an “onion model” of reflection (see fig. 1) to help teachers better understand reflection as a process of seeking “alignment” between their core beliefs and their actions. As a result of his research and workshops, he proposed that reflection should focus on “how to translate one’s core qualities into concrete behavior in a specific situation” in a quest to attain “complete ‘alignment,’” a condition that admittedly may “take a lifetime to attain, if attained at all.”[17] While this process may lead to “great uneasiness” in some instances, it will also lead to teachers who teach with greater power and have a greater impact in the classroom as their professional development translates their core beliefs into effective classroom behaviors.

The Church-produced Teaching, No Greater Call manual exhorts teachers to “continually reflect on our effectiveness as teachers,”[18] and the CES-produced Administer Appropriately Handbook suggests that leaders who have a habit of “reflecting on related past experiences”[19] will have greater success in their assignments. However, not much research has been done on teacher reflection in religious education, including among S&I faculty. [20] Thus it was determined that a study of reflection among professional seminary teachers in S&I might increase understanding of reflection and promote more effective reflection as a function of professional development.

Fig. 1. Korthagen’s “onion model” of reflection.

Fig. 1. Korthagen’s “onion model” of reflection.

A Model of Teacher Reflection for Religious Educators

From a recent qualitative study on the reflective practices of full-time seminary teachers, a model of teacher reflection has been developed to show how religious educators might approach teacher reflection in a way that will contribute to sustained professional development.[21] This study sought to identify the reflective practices of professional seminary teachers and better understand how teachers perceived these practices as having an impact on their professional development. Forty-seven full-time seminary teachers participated in this study through an online survey, and six of these teachers participated in observations and interviews. These six teachers also contributed documents, such as professional journal writing samples and copies of their Professional Growth Plans, for further analysis.[22]

While Korthagen’s model of reflection provided important background understanding for professional reflection in educational settings, the primary theoretical framework for this study was a model created by Neville Hatton and David Smith, which includes four levels of reflection: technical, descriptive, dialogic, and critical.[23] The survey and interviews for this study were designed to identify reflective practices that corresponded to the four levels of reflection and how teachers engaged in these four levels of reflection. The study also sought to better understand how teachers felt their engagement in these reflective practices contributed to their overall professional development.

This study showed that there are a wide variety of potentially reflective practices among professional seminary teachers in S&I. The following table summarizes some reflective practices that teachers, instructional leaders, and administrators should consider as they focus on incorporating reflection into professional development activities and programs. The institutional practices are those that S&I generally promotes or encourages through policy, training, or other administrative means. The informal practices are those that seem to occur on a more localized basis, or that seem to happen without any open general administrative assertion or encouragement per se.

Table 1. Reflective practices among professional seminary teachers

|

Institutional |

Informal |

|

|

More common |

· Teachers observing other teachers · Supervisors observing teachers · Attending inservice training · Reading professional material (i.e., handbooks) · Seeking higher education · Professional training programs |

· Discussions with colleagues · Collaborative lesson planning · “Lesson correction reflection” · Professional development writing activities · Evaluating performance against personal goals · Learning from mentors |

|

Less common |

· Professional Growth Plans · Writing about observations · Attending professional conferences · Professional learning communities |

· Having lesson plans reviewed · Skill-focused evaluations · Reviewing other teachers’ lesson plans · Reading professional journals |

Comments from a majority of teachers interviewed in this study suggested that teachers do not perceive these various practices as being connected, harmonized, or integrated in any systematic way as part of a comprehensive plan for their professional development.

Some of these teacher reflection practices tended to lead teachers to engage in specific levels of reflection proposed by Hatton and Smith. However, none of the reflective practices identified in this study could be said to lead exclusively to any particular level of reflection. Thus it is important for professional seminary teachers (and those who supervise them) to understand that the many activities, tools, or forms available in S&I will not necessarily lead to given levels of reflection by nature of the inherent design of the form itself. The direction of a teacher’s reflection will be determined by the intents and attitudes of the persons who employ these various forms. Assessment and evaluation are, therefore, essential components in guiding the professional reflection of teachers if that reflection is to have an optimal impact on the professional development of the individual teacher. It should also be noted that forms of reflection can be used to effectively lead to multiple levels of reflection when carefully designed and deliberately employed.

The next four sections will define each level of reflection and then present the findings from this study relative to the practices, processes, and impact of teacher reflection among professional seminary teachers. The fifth section will present a model of teacher reflection based on these findings and a brief case description that will hopefully help teachers and supervisors in S&I more fully understand the process of reflection in a way that will contribute to sustained professional development that results in their having an increasingly greater impact with students in the classroom.

Technical reflection. The first level of reflection posited by Hatton and Smith, called technical reflection, involves “decision-making about immediate behaviours or skills . . . but always interpreted in light of personal worries and previous experiences.”[24] This level of reflection involves an examination of one’s use of teaching skills or general competencies (whether content-based or methodological) in a controlled, small setting, such as the teacher’s own classroom. This usually takes place in a “reporting” fashion, whereby the teacher simply recounts what he or she did without providing reasons or justification for the decision or course of action.

When teachers in this study engaged in technical reflection, they most frequently talked about evaluating student participation in seminary, thinking about the need for classroom discipline, lesson pacing, and “lesson correction reflection.” A teacher in this study generated the phrase “lesson correction reflection” to describe the kind of technical reflection seminary teachers engage in when thinking about how they can improve skills, competencies, and behaviors to make a lesson more effective. One teacher posed the following question as a means for engaging in this kind of reflective experience, “If someone were to evaluate, . . . talking about a baseball pitch, did I get the mechanics right?”

One interesting finding of this study was that when the seminary teachers interviewed in this study engaged in technical reflection, they focused mainly on student participation. When teachers talked about student participation as an end in itself without any explanation as to why the participation was important or evaluating whether or not the participation was necessarily substantive, this represented technical reflection. While focusing on student participation can be valuable, discussion of this issue in the descriptive reflection section will show the potential problems of a teacher focusing strictly on promoting student participation without considering the purposes for doing so.

Teachers need to engage in reflective practices that evaluate their effective use of teaching skills. These practices cannot be viewed as insignificant or of little importance as teachers claim to focus on the larger goals of the S&I Objective or employing the fundamentals of the TLE. Teachers must also be cautious not to overemphasize technical reflection to the point that the pedagogy becomes an end in itself, as seemed to be the case in this study, with the emphasis on student participation in the classroom. Religious educators may have a propensity to do this as they subordinate the higher moral and spiritual purposes of their teaching to pedagogy.

As with all levels of reflection, technical reflection needs to be connected to other levels of reflection in order to be effective in promoting professional development among religious educators. When a teacher is observed, he may then report what happened in his classroom to a colleague or supervisor—this is technical reflection. However, if he then engages in a collegial evaluation and exchange of ideas with a colleague or supervisor—to be discussed in more detail shortly as one form of dialogic reflection—the teacher can weigh differing perspectives with his own and then exchange, modify, or incorporate those competing ideas. However, observers and teachers should be aware that the level of trust in their relationship and the degree to which the teacher being observed feels secure will have a tremendous impact on that teacher’s willingness and capacity to improve through such experiences.

While it may seem reasonable that technical reflection would inevitably lead to descriptive reflection (wherein teachers explain their actions in context of their rationale for those actions), such a transition was not automatic among professional seminary teachers. In fact, it was only rarely the case. According to the data collected from the teachers in this sample, no patterns or trends emerged that showed teachers describing what they did and then independently explaining why they did it.

Korthagen surmised that teachers who are stuck in technical reflection and focus primarily on developing skills, behaviors, and competencies that never lead to other levels of reflection will stagnate in their professional development.[25] Without any inclination to consider the rationale behind their actions, teachers cannot evaluate whether their behaviors are effective or ineffective, good or bad, successful or unsuccessful—or if there is any way they might do things differently or better. Fortunately, none of the teachers interviewed in this study seemed to fit that description.

Descriptive reflection. The next level of reflection in Hatton and Smith’s model is descriptive reflection, which is “not only a description of events but some attempt to provide reason [or] justification for events or actions” while taking into account “multiple factors and perspectives.”[26] When teachers in this study engaged in practices that led to descriptive reflection, they most often talked about such issues as writing as teacher reflection practice, evaluating student participation in seminary, reconsidering emphasis on students over content, and planning for student analysis/

An example of the difference between the technical level and the descriptive level is how teachers talked about evaluating student participation in seminary. Evaluating student participation dominated all other categories of technical reflection—teachers talked about this twice as much as the next highest category of technical reflection. In most interviews, teachers talked about student participation as if its mere presence was an indication of successful teaching, which may lead to the following error. While evaluating a national teacher education program, Thomas Popkewitz claimed that an “educator’s focus rendered the intellectual content (substance) of the lessons inconsequential. Substance was subordinated to pedagogic form and style.”[27] He said that this was most likely to happen “when enjoyment became one of the primary objects of instruction.” If “success was indicated by the degree to which students ‘felt good’ about the lesson, and whether they ‘participated’ actively in the lesson and its attendant discussion,” then pupil involvement would replace student understanding of the substance of the lesson.[28]

Some contemporary researchers have argued that this has taken place in religious education in America, leading to a shallow understanding of basic beliefs and religious practices among teenagers in America.[29] Rymarz warned about this danger specifically in religious education settings when he argued that “one important reason behind the lack of religious content knowledge [among students] is the reluctance of teachers to move beyond the experiential world of students.”[30] The guiding principles of teaching in S&I, as outlined in the Objective and the TLE, propose that effective religious education occurs when teachers maintain an appropriate balance between teaching content and engaging students in the learning process.

By engaging in descriptive reflection, teachers may be more likely to ensure that student participation in seminary is accomplishing the purposes of S&I—for example, giving students opportunities to practice articulating their beliefs so they can share them with others. Unfortunately, teachers discussed this topic in descriptively reflective terms less than half as often as they did when talking about student participation in technically reflective terms. Thus teachers are more likely to talk about student participation as an inherently desirable or positive outcome of their teaching than they are to talk about why they want it or what they hope to accomplish with it. Or in other words, teachers may be prone to talk about student participation as the end goal rather than as a means to other objectives.

Descriptive reflection is critical for S&I teachers because it requires them to explain the rationale behind their decisions in the classroom—to engage in “deliberate thinking about action with a view to its improvement.” A few of the teachers in this study did engage in descriptive reflection via reflective writing about their own teaching or through evaluating their teaching performance against personal teaching goals; however, they reported feeling that they had little time to engage in these practices regularly. And when they did engage in these practices, they did not include the S&I Objective or TLE as an explicit part of their rationale.

Through analysis and interpretation of the data in this study, descriptive reflection emerges as a key to a teacher’s ability to integrate the four levels of reflection and attain the benefits for doing so. The more teachers engage in “reflection-on-action,” the more likely they are to develop the ability to engage in “reflection-in-action.”[31] Descriptive reflection can lead S&I teachers to align their classroom behaviors more closely with both their mission and values as religious educators and to the mission and objectives of S&I. While teachers are often implicitly striving to accomplish the aims of the S&I Objective and TLE, practicing more consistent descriptive reflection could lead to greater unity between administration, supervisors, and teachers so that efforts at professional development in S&I are designed and perceived as being part of a cohesive approach to improving teaching. Teachers who articulate an explicit rationale for their classroom behaviors through descriptive reflection could also more effectively bridge the gap between “espoused theories” and “theories in use” so that their “hybrid theories of practice” become more consistent and easier to evaluate and improve.

Teachers who do not become skilled in descriptive reflection risk two potential problems. On one hand, teachers arrested in the supposedly more practical realm of technical reflection may risk being continually baffled by the fact that a particular method or activity works in one class but not in another, as they continue to blindly employ the same pedagogical practices or activities despite classroom dynamics, the needs of individual students, and subject matter differences. On the other hand, teachers arrested in the supposedly more philosophical realm of critical reflection (to be discussed later) risk ethereal discussions and ponderings over ideas and concepts pertaining to identity, mission, and values without giving sufficient consideration to how effective pedagogical practice impacts students.

Dialogic reflection. The third level of teacher reflection proposed by Hatton and Smith is dialogic reflection. When teachers engage in dialogic reflection, they are “weighing competing claims and viewpoints, and then exploring alternative solutions.”[32] Teachers in this study reported that the most common ways they experienced dialogic reflection were working with the principal; seeking and receiving feedback, as well as giving feedback to others; and being empowered by education. This last way has to do with how teachers feel their educational background prepared them for teaching and how it informs their teaching practice. Another ways that teachers engaged in dialogic reflection was by reading professional religious education material, such as the Religious Educator or talks from Church and S&I leaders posted on the S&I website.

The analysis and interpretation of the data indicate that the professional seminary teachers in this study felt that their principal was the key figure in their dialogic reflective practices. As the primary instructional leader in every seminary building, the principal is in the best position to influence the improvement of teaching among seminary faculty. He potentially has more direct instructional leadership interface time with seminary teachers than any other individual has with S&I teachers. Teachers in the study had fairly strong opinions about the difference that a principal made, or could make, in their professional development.[33] Working with the principal obviously overlaps with the practice of seminary teachers seeking, receiving, and giving feedback, all of which also contributed significantly to their professional development as dialogically reflective practices. Seeking, giving, and receiving feedback also overlaps with other dialogically reflective practices, such as collaborating with faculty to prepare lessons and consulting with colleagues to solve problems. The seminary teachers in this study recognized that dialogic reflection with an instructional leader and with immediate colleagues or faculty could have a positive impact on their professional development.

Teachers are more likely to consider student participation as the end goal rather than as the means to other objectives. Matt Reier, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Teachers are more likely to consider student participation as the end goal rather than as the means to other objectives. Matt Reier, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Dialogic reflection may not be seen as having a clear connection to other levels of reflection. However, this apparent disassociation may be a result of the current S&I culture, in which dialogic reflection is so heavily emphasized that its connection is almost invisible because of its obviousness, like a fish who doesn’t realize he is swimming in water. Four of the six teachers interviewed in this study had been teaching for more than ten years. These teachers all reported feeling a significant shift within the last decade of S&I’s approach to professional development, whereby teachers were more strongly encouraged to actively seek, give, and receive feedback. Although several teachers in the study reported feeling that the modes of operation for this practice were not as well defined or sufficiently implemented (by teachers and principals alike) as they should have been, there has been a deliberate effort on the part of S&I administration and supervisors to encourage more dialogic reflection. The qualitative data from interviews, observations, and documents in this study support this trend by showing dialogic reflection as the second most common form of reflection among professional S&I seminary teachers in this study.

Most of the potentially reflective practices identified among professional seminary teachers in S&I inherently promote or support dialogic reflection. These practices include teachers observing other teachers and supervisors observing teachers, and the following activities: holding inservice meetings, seeking higher education, reading S&I handbooks and materials, using the Professional Growth Plan (probably the least effectively implemented method identified in this study), attending professional conferences, engaging in professional learning communities (i.e., apprentice seminars and “cluster groups”), discussing teaching practices with colleagues, planning lessons collaboratively, learning from mentors, reviewing lesson plans, and reading from professional journals. In all these potentially reflective practices, teachers are—or can be—encouraged to weigh competing claims and viewpoints as they explore possible solutions to the problems and challenges they face in their teaching and their professional development. Teachers who engage regularly in dialogically reflective practices avoid the insular dangers of a form of “intellectual inbreeding,” wherein teachers avoid broadening horizons or seeking improvement out of convenience, fear, or insecurity in one form or another.

Dialogic reflection can cross all levels of reflection in an effort to consistently engage the teacher in dialogue with others, as part of the quest for sustained professional development. “The typical milieu of the school [or seminary] makes it difficult for teachers to see themselves as learners, to reflect on practice, and to create a collaborative, intellectual environment that sustains them as a community of learners.”[34] Teachers in individual classrooms and offices can become somewhat isolated without any form of dialogic reflection. A skilled and trusted dialogic partner can provide a helpful objective “mirror” for a teacher stuck in technical reflection. In dialogic reflection, teachers can compare what they think happened in class with what other teachers or supervisors observed. Skilled dialogic partners can ask teachers searching questions, or offer suggestions, that help them articulate the rationale behind their behavior as teachers. Skilled dialogic partners can also help teachers ask questions or put forth ideas of a critically reflective nature that help teachers consider their alignment with institutional objectives and their impact on the students, the rest of the faculty, and the larger community.

Critical reflection. Hatton and Smith wrote that there are three primary aspects of critical reflection in which professional educators might engage: (a) “seeing as problematic, according to ethical criteria, the goals and practices of one’s profession,” (b) “thinking about the effects upon others of one’s actions,” and (c) “taking account of social, political and/

Critical reflection was perhaps the most interesting level of reflection to investigate and analyze throughout this study. On the survey and in interviews, professional seminary teachers in S&I did not generally consider elements of critical reflection pertaining to race, gender, social justice, as found in most professional religious education journals,[37] and even the Religious Educator.[38] In fact, they seemed quite reticent to discuss such issues when invited to do so during interviews. The data collected from one survey respondent indicated that he had a tendency to engage more regularly in critical reflection. However, even though he mentioned issues pertaining to gender and community during his interview, he did not engage predominantly in the kind of critical reflection that might be found in other religious education journals and books.

While there was some minor evidence of all three aspects of critical reflection in this study, the seminary teachers in this study seemed focused on “thinking about the effects upon others of one’s actions.” The largest amount of data among all levels of reflection—technical, descriptive, dialogic, or critical—pertained to the critical reflective category that dealt with “promoting the spiritual growth and development of students.” While the S&I Objective and TLE were generally not mentioned specifically in connection with critical reflection, teachers in this study were in harmony, in principle at least, with these institutional aims.

However, even though teachers seem to readily engage in critical reflection, more so than any other level of reflection, none of the reflective practices identified among the professional S&I seminary teachers seemed to effectively transmit a teacher’s critical reflection into action in the classroom. While two of the more experienced teachers tended to move from technical reflection to critical reflection in the interviews more than other teachers, there did not appear to be any particular practice that encouraged teachers to regularly evaluate or explain how particular classroom behaviors or pedagogical decisions related to “promoting the spiritual growth and development of students.” With only a few minor exceptions, teachers generally said that they “hoped” what happened in the classroom would lead to this outcome, but they generally didn’t seek to explain specifically “how” they thought what they did in the classroom would lead to that outcome. This is not to say that the teachers in this study couldn’t do that—because they showed effectively in the interviews that they could—but this is just to say that they didn’t report that there was any particular reflective practice—either formal or informal, personal or institutional—that encouraged them to make this connection on a regular basis.

This lack of connection between the “espoused theories” of S&I professional seminary teachers (i.e., the S&I Objective and the TLE, even when not articulated as such by specific terminology) could be overcome through the effective evaluation of “theories in use” (i.e., technical practices and reflection) via descriptive and dialogical reflective means to generate effective “hybrid theories of practice,” as mentioned earlier by Argyris & Schön. It is important for seminary teachers to make explicit connections between the aims of their critical reflection and their technical reflection via descriptive and dialogic reflection. This helps them avoid the “directionless change” that comes from “competence without purpose” as well as the “inefficiency and frustration” that comes from “purpose without competence.”[39]

An integrated model and case description of teacher reflection as a function of sustained professional development. Each level of reflection serves a useful purpose in the professional development of religious educators. However, professional development will be greatly enhanced if teachers will learn to integrate the various levels of reflection as a function of their professional development. This integration of the levels of reflection can accomplish four related purposes that have been referred to previously in this study. First, teachers who can effectively integrate the four levels of “reflection-on-action” will move closer to “reflection-in-action.” Hatton and Smith described “reflection-in-action” as “the ability to apply, singly or in combination, qualitatively distinctive kinds of reflection (namely technical, descriptive, dialogic, or critical) to a given situation as it is unfolding. In other words, the professional practitioner is able consciously to think about an action as it is taking place, making sense of what is happening and shaping successive practical steps using multiple viewpoints as appropriate.”[40]

One teacher, in an interview for this study, shared the following basketball analogy to illustrate “reflection-in-action:” “When Kobe [Bryant] is driving the ball down the court, he sees a certain opening. Kobe doesn’t call timeout, go over, get into his files, and say, ‘Oh yeah, this move has worked on that situation.’ He doesn’t even think about it; he just does it. I’d like to become the kind of teacher that has . . .a thousand tools at my disposal that I use often enough that at any moment I can grab that tool.” Just like a professional athlete, professional teachers are not likely to develop this kind of reflective automaticity without an understanding of and practice with the various types of reflection through activities that engage them in actual reflection.

The second objective that can be accomplished with the successful integration of the various levels of reflection is the “alignment” between a teacher’s core sense of identity, beliefs, and mission with his or her competencies, skills, and behaviors in the classroom. Teachers who develop this alignment—or, who are at least progressing toward it, since Korthagen admitted that complete alignment may “take a lifetime to attain, if attained at all”—increase their effectiveness in the classroom by having a clarified understanding of their purpose and a clear direction for how to accomplish it. This will likely also increase a teacher’s “professional trustworthiness”[41] that one religious education professor argued will enhance the student-teacher relationship, which is so vital in religious education. Without this alignment, teachers constantly risk disruptions by “gestalts”; these are the default behaviors that teachers employ independent of, and often contrary to, professional training or espoused theories[42] as they face inevitable dynamic challenges in their efforts to teach students. Teachers who cease striving for this professional alignment also face personal stagnation in their professional development as they potentially fixate on only one level of reflection.

Third, religious educators who integrate the various levels of teacher reflection enable themselves to see more clearly their “espoused theories,” identify incongruencies between their “espoused theories” and their “theories-in-use,” and develop working and ever-improving “hybrid theories of practice.” As teachers evaluate their actions, endeavor to make implicit assumptions explicit, and formulate new lenses for viewing and evaluating their practice—this includes persevering in “serious reflection” despite potential “great uneasiness”—they become more effective and more satisfied in their work.

Fourth, as teachers overcome the discomfort of their “cognitive dissonance”[43] and integrate the four levels of reflection addressed in this study, they move toward Glickman’s ideal of teachers who “assume full responsibility for instructional improvement.”[44] Of course, this does not refer to teachers who engage in isolated professional development (this would completely ignore the dialogic level of reflection) but to teachers who successfully integrate the four levels of reflection and take primary responsibility for their own sustained professional development.

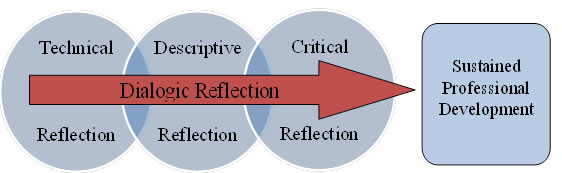

The following model (fig. 2) illustrates how the four levels of reflection operate within the reflective practices and processes of the professional seminary teachers in this study. In this model, descriptive reflection is shown as a critical link between technical reflection and critical reflection. The arrow shows how dialogic reflection crosses through the other three levels of reflection and integrates all levels of reflection in a process that leads to sustained professional development. This also reflects the emphasis on dialogic reflection found among the S&I teachers in this study and how the various dialogically reflective practices in S&I support and promote teacher engagement in other levels of reflection.

Fig. 2. Integrated model of reflection.

Fig. 2. Integrated model of reflection.

Perhaps a brief case description will illustrate how a professional seminary teacher, with the help of an informed and attentive instructional leader, can use this model to enhance his professional development efforts. While this illustrative example is hypothetical and includes more elements of reflection than might reasonably be pursued by a single teacher, it does represent actual practices and processes employed by teachers in this study.

Brother Anderson arranges several exploratory classroom observations with his principal. Each observation, with its preobservation and postobservation visits, focuses on a different aspect of Brother Anderson’s teaching.[45] For example, one observation focuses on Brother Anderson’s use of questions in class. Another observation focuses on student participation. Another focuses on how Brother Anderson’s choice of content and methods help him focus on the Objective of S&I with his students. After each observation, Brother Anderson writes a brief summary of what he did in class, why he chose to do it, and how his decisions relate to the S&I Objective and the TLE. After reviewing his notes and pondering the feedback from his principal, Brother Anderson uses the Professional Growth Plan to formulate a goal to work on student participation. He includes in his goal statement specific objectives he would like to accomplish, why he thinks student participation is important, and how participation will accomplish the S&I Objective. He shares this goal with his principal.

Subsequent classroom observations with the principal focus on evaluating student participation methods and whether Brother Anderson and the principal feel that the purposes for the participation are being accomplished. During each preobservation visit, Brother Anderson gives a copy of his lesson plan to the principal and together they discuss how the student participation in that lesson will help Brother Anderson accomplish his goals. The postobservation visits focus on these same objectives. Brother Anderson also asks his students occasionally to share with him how they feel about their participation in class. Sometimes Brother Anderson and the principal plan a lesson together to see how they could incorporate effective participation techniques in a way that will help the doctrines and principles of the lesson be meaningful for students.

The principal also encourages Brother Anderson to search the “Talks for Teachers” web site and the Religious Educator for material that might help him and the seminary faculty to improve student participation in their classrooms. He then asks Brother Anderson to give a faculty inservice meeting on the subject to share what he has learned and lead a discussion with other teachers. Brother Anderson and his principal use the Regular Results Discussion form monthly to discuss how Brother Anderson’s efforts to improve student participation are helping him to promote the spiritual growth of his students. When they feel that sufficient progress has been made and that Brother Anderson is ready to focus on another goal, they might employ similar reflective procedures to help Brother Anderson continue this pattern of sustained professional development.

Conclusion

Most teachers, including religious educators, engage in some sort of reflection whether they articulate it as such or not. The teachers interviewed in this study demonstrated and expressed both the eagerness and ability to engage more deliberately in reflection that would help them improve their practice as religious educators. More research on the subject of reflection would be beneficial for our understanding of this aspect of professional development, including studies that explore other models of teacher reflection and more detailed investigation of the role of instructional supervisors in the reflective process. It is hoped that this study and the model of reflection generated by it will give religious educators a foundational framework for pursuing, discussing, and improving their reflective practices as we strive to fulfill both our contractual and covenantal obligations to the Church and to the Lord. We will then have a greater impact on the youth and young adults of the Church as we help them understand and rely on the teachings and Atonement of Jesus Christ, qualify for the blessings of the temple, and prepare themselves, their families, and others for eternal life with our Heavenly Father.

Notes

[1] Elder W. Rolfe Kerr first challenged seminary and institute faculty to “increase our impact” in a talk titled “On the Lord’s Errand,” CES Satellite Training Broadcast, August 2005 (Salt Lake City: Church Educational System, 2005), 7–8. He again addressed the charge to “increase our impact” with students in “Clarity of Focus and Consistency of Effort,” Address to CES Religious Educators, February 3, 2006 (Salt Lake City: Church Educational System, 2006). Garry K. Moore, CES Administrator—Religious Education and Elementary and Secondary Education, reinforced this emphasis in “Vital Principles for Religious Educators,” CES Satellite Broadcast, August 7, 2007 (Salt Lake City: Church Educational System, 2007).

[2] Church Educational System, Administering Appropriately: A Handbook for CES Leaders and Teachers (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2003), 15.

[3] Administering Appropriately, 16.

[4] For more on “spiritual reflection” as a necessary aspect of professional development, see Clifford Mayes, “Cultivating Spiritual Reflectivity in Teachers,” Teacher Education Quarterly 28, no. 2 (2001): 5–22; Clifford Mayes, “Deepening our reflectivity,” The Teacher Educator 36, no. 4 (2001): 248–64; and Clifford Mayes, “A transpersonal model for teacher reflectivity,” Journal of Curriculum Studies 33, no. 4 (2001): 477–93.

[5] Carl D. Glickman, Stephen P. Gordon, and Jovita M. Ross-Gordon, SuperVision and Instructional Leadership: A Developmental Approach, 6th ed. (Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, 2004), 208.

[6] Grant C. Anderson, former assistant administrator in S&I, encouraged S&I faculty to strive for consistent improvement in personal and professional development in “Living a Life in Crescendo,” CES Satellite Training Broadcast, August 4, 2004 (Salt Lake City: Church Educational System, 2004).

[7] Neville Hatton and David Smith, “Reflection in Teacher Education: Towards Definition and Implementation,” Teaching and Teacher Education 11 (January 1995), 40; see also Jo Blase and Joseph Blase, Handbook of Instructional Leadership: How Successful Principals Promote Teaching and Learning, 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2004), 88.

[8] See Church Educational System, Teaching the Gospel Handbook (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2001), 19–24.

[9] See Eric Marlowe, “Positive Classroom Discipline,” Religious Educator 11, no. 2 (2010): 121–37.

[10] For more on the work of Chris Argyris and Donald Schön, see the following: Chris Argyris and Donald A. Schön, Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1974); Donald A. Schön, The Reflective Practitioner (New York: Basic, 1983); Donald A. Schön, Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1987); and Donald A. Schön, ed., The Reflective Turn: Case Studies in and on Educational Practice (New York: Teachers College Press, 1991).

[11] Argyris and Schön, Theory in Practice, 6–7.

[12] Argyris and Schön, Theory in Practice, 195.

[13] Argyris and Schön, Theory in Practice, 32–33. Elder David R. Stone of the Seventy also warned, “People in every culture move within a cocoon of self-satisfied self-deception, fully convinced that the way they see things is the way things really are” (“Zion in the Midst of Babylon,” Ensign, May 2006, 91). For more on the subtle and systematic ways that people engage in self-deception, see Arbinger Institute, Leadership and Self-Deception: Getting Out of the Box. (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2002). For a similar treatment of how individuals and institutions can fall victim to a form of self-deception that Lee G. Bolman and Terrence E. Deal simply call “cluelessness,” see Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice, and Leadership, 3rd ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003).

[14] See Herbert R. Kohl, “Ten Minutes a Day,” in S.O.U.R.C.E.S.: Notable Selections in Education, ed. Fred Schultz, 3rd ed. (Guilford, CT: McGraw-Hill/

[15] President James E. Faust, “‘We Seek After These Things,’” Ensign, May 1998, 43.

[16] Fred A. J. Korthagen, “In Search of the Essence of a Good Teacher: Towards a More Holistic Approach in Teacher Education,” Teaching and Teacher Education 20 (2004): 78.

[17] Korthagen, “Essence of a Good Teacher,” 91, 87.

[18] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Teaching, No Greater Call: A Resource Guide for Gospel Teaching (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1999), 236.

[19] Administering Appropriately, 23.

[20] For a review of CES-related research over the last several decades, see Eric P. Rogers, (2009). Bibliography of CES-related research. Retrieved from http://

[21] For the entire study, see Ryan S. Gardner, “Teacher Reflection among Professional Seminary Faculty in the Seminaries and Institutes Department of the Church Educational System” (PhD diss., Utah State University, 2011).

[22] This qualitative study employed four purposeful sampling strategies to select participants: homogeneous sampling, maximal variation sampling, extreme case sampling, and theory or concept sampling; see John W. Creswell, Educational research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 2nd ed. (Columbus, OH: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005), 204–6.

[23] See Hatton and Smith, “Reflection in Teacher Education.” Qualitative researchers recommend using multiple theoretical lenses when doing qualitative research in order to better understand the multiple facets of the phenomenon being studied. See Harry Wolcott, Writing Up Qualitative Research (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2001); and Kathy Charmaz, “Grounded Theory as an Emergent Method,” in Handbook of Emergent Methods, eds. Sharlene N. Hesse-Biber and Patricia Leavy (Guilford, CT: Guilford, 2008), 155–70.

[24] Hatton and Smith, “Reflection in Teacher Education,” 45.

[25] Korthagen, “Essence of a Good Teacher,” 90–93.

[26] Hatton and Smith, “Reflection in Teacher Education,” 48.

[27] Thomas S. Popkewitz, Struggling for the Soul: The Politics of Schooling and the Construction of the Teacher (New York: Teachers College Press, 1998), 85.

[28] Popkewitz, Struggling for the Soul, 90.

[29] See Kenda C. Dean, Almost Christian: What the Faith of Our Teenagers Is Telling the American Church (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010); and Christian Smith, Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005). However, Dean and Smith have both pointed out that LDS youth seem to fare better than typical American youth in both understanding and articulating their beliefs. This has been corroborated in part by research by Bruce A. Chadwick, Brent L. Top, and Richard J. McClendon, Shield of Faith: The Power of Religion in the Lives of LDS Youth and Young Adults (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City, Deseret Book, 2010).

[30] Richard M. Rymarz, “Who Is This Person Grace? A Reflection on Content Knowledge in Religious Education,” Religious Education 102, no. 1 (2007): 62.

[31] Hatton and Smith, “Reflection in Teacher Education,” 45.

[32] Hatton and Smith, “Reflection in Teacher Education,” 45.

[33] Aside from the books by Blase and Blase and Glickman, Gordon, and Ross-Gordon already cited, a significant amount of research confirms the important role of the principal as an instructional leader in any educational institution. For analysis and summary of this research, see also Carl D. Glickman, Leadership for Learning: How to Help Teachers Succeed (Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2002) and Robert J. Marzano, Timothy Waters and Brian McNulty, School Leadership That Works: From Research to Results (Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2005).

[34] Blase & Blase, Handbook of Instructional Leadership, 93–94.

[35] Hatton and Smith, “Reflection in Teacher Education,” 45.

[36] Hatton and Smith, “Reflection in Teacher Education,” 49.

[37] See journals such as Religion & Education, Religious Education, or the journal published by the American Academy of Religion.

[38] See Ryan Jenkins, “‘Peaceable Followers of Christ’ in Days of War and Contention,” Religious Educator 10, no. 3 (2009): 87–102; Nick Eastmond, “Beneath the Surface of Multicultural Issues,” Religious Educator 9, no. 3 (2008): 91–99; and Royden Olsen, “Transcultural Considerations in Teaching the Gospel,” Religious Educator 7, no. 3 (2006): 87–96.

[39] Glickman, Gordon, and Ross-Gordon, SuperVision and Instructional Leadership, 476.

[40] Hatton and Smith, “Reflection in Teacher Education,” 46.

[41] Matthew L. Skinner, “‘How Can Students Learn to Trust Us As We Challenge Who They Are?’ Building Trust and Trustworthiness in a Biblical Studies Classroom,” in Teaching Reflectively in Theological Contexts: Promises and Contradictions, ed. Mary E. Hess and Stephen D. Brookfield (Malabar, FL: Krieger, 2008), 99–100.

[42] Korthagen, “Essence of a Good Teacher,” 81.

[43] Glickman, Gordon, and Ross-Gordon, SuperVision and Instructional Leadership, 137–39.

[44] Glickman, Gordon, and Ross-Gordon, SuperVision and Instructional Leadership, 208.

[45] Both Elliot Eisner (“The Perceptive Eye: Toward the Reformation of Educational Evaluation,” Occasional Papers of the Stanford Evaluation Consortium, Stanford University, 1975) and Harry Wolcott (see Transforming Qualitative Data: Description, Analysis, and Interpretation [Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1996]) have pointed out the importance of focused evaluations and observations as a means to increasing understanding of any event or phenomenon.