The Role of Lawyers in the American Revolution

Christopher A. Cole

Christopher A. Cole, "The Role of Lawyers in the American Revolution," Religious Educator 12, no. 2 (2011): 47–67.

Christopher A. Cole (chris.cole68@gmail.com) was an attorney in Alpine, Utah when this was written.

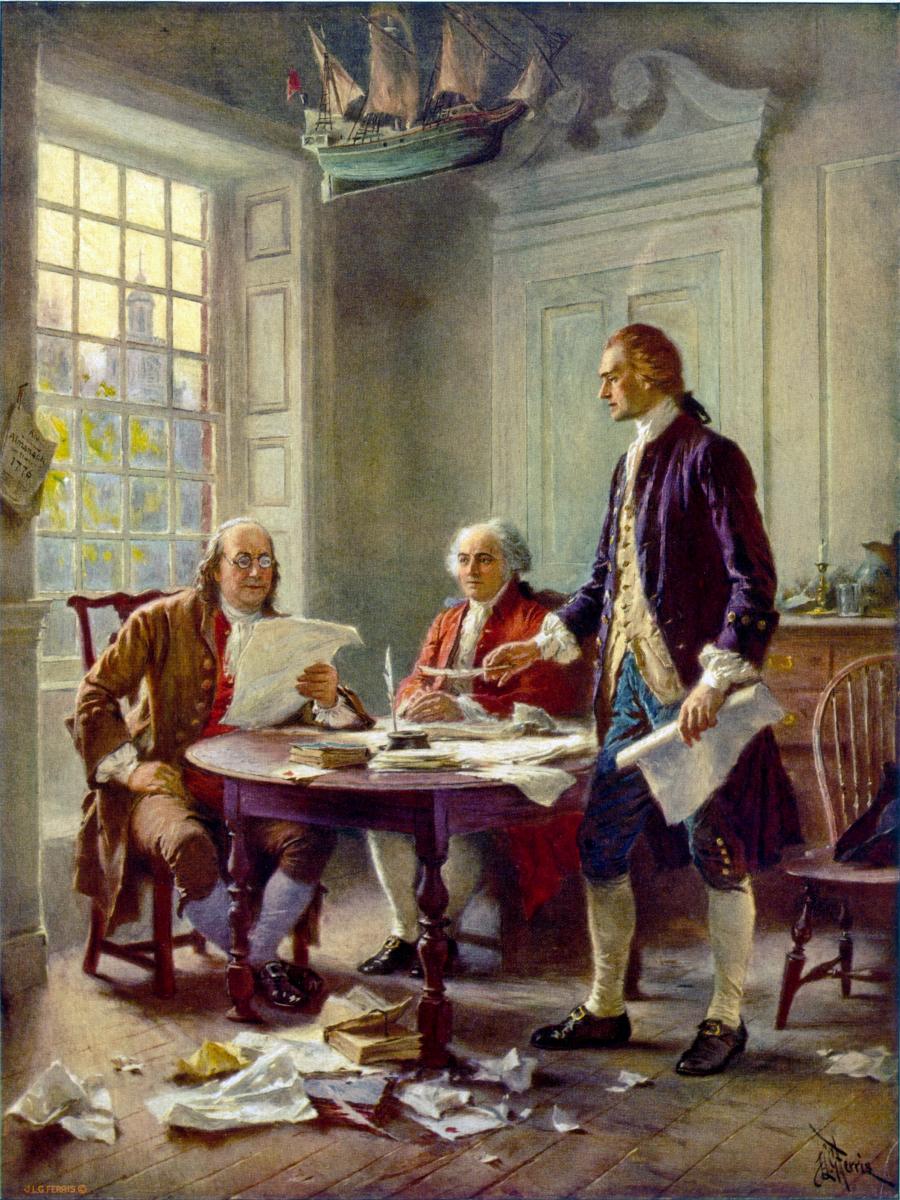

Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin meet to review a draft of the Declaration of Independence. Jeon Leon Gerome Ferris (1863-1930), Writing the Declaration of Independence.

Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin meet to review a draft of the Declaration of Independence. Jeon Leon Gerome Ferris (1863-1930), Writing the Declaration of Independence.

Through the ages, prophets have foreseen and testified of the divine mission of America as the place for the Restoration of the gospel in the latter days. Beginning with the European Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment, piece after piece of the Lord’s plan fell into place, ultimately leading to Joseph Smith’s First Vision in 1820. A review of colonial lawyers’ activities reveals their significant role in laying the groundwork for this long-awaited event.

To the Prophet Joseph Smith, the Lord confirmed both the Revolutionary War and the founding of America as culminating preludes to the Restoration: “And for this purpose have I established the Constitution of this land, by the hands of wise men whom I raised up unto this very purpose, and redeemed the land by the shedding of blood” (D&C 101:80).

President Joseph F. Smith put into perspective the import of this revelation to Joseph Smith. “This great American nation the Almighty raised up by the power of his omnipotent hand, that it might be possible in the latter days for the kingdom of God to be established on earth. If the Lord had not prepared the way by laying the foundations of this glorious nation, it would have been impossible (under the stringent laws and bigotry of the monarchial governments of the world) to have laid the foundations for the coming of his great kingdom.”[1]

From the foregoing prophesies and teachings a premise becomes clear; those Founding Fathers inspired in the cause of America were concurrently engaged in the work of the Restoration. The one was preparatory to the other. And as we will see in the chain of these events, many of these Founding Fathers, through the instrumentality of their legal training and experience, became central characters in preparing this land for the Restoration.[2]

Appropriately, a consideration of the work of the Founding Fathers should begin with a review of who they were. Unfortunately, no generally accepted definition exists of who actually belongs in this group. Some credit Warren G. Harding for having first coined the phrase Founding Fathers as he spoke as an Ohio senator at the 1916 Republican National Convention. However, neither he nor any of the myriad sources on the subject seem to find consensus as to who exactly qualifies for the title. Most would agree that at the very least, elected delegates who debated and voted the issues, and certainly those who signed the key documents, would fall into this company. Perhaps others, simply by virtue of their commanding influence for independence and self-rule, such as the uniquely-influential writer Thomas Paine, should also be numbered among the Founding Fathers.

The Lawyer-Founders

As a general overview, consider the following with respect to three of the most important documents in American history, from whence the appellation of “lawyer-founders” as a subset of the Founding Fathers may be appropriate.

First, of the fifty-six signers of the Declaration of Independence, at least twenty-eight were lawyers.[3] It is well known that the document was authored by the tall and soft-spoken lawyer from Monticello. Perhaps less well known is the fact that the Continental Congress actually appointed a committee of five men for this task, Benjamin Franklin being the only non-lawyer among them. The four lawyers included John Adams, Robert R. Livingston Jr., Roger Sherman, and Thomas Jefferson. In their collective wisdom, they relied on what Adams described as Jefferson’s “happy talent for composition” and “peculiar felicity of expression” in choosing the comparatively youthful Virginian (only thirty-three years of age) as the principle draftsman.[4]

Second, the Articles of Confederation, initiated in 1776 but not fully ratified by all thirteen colonies until 1781, became the governing instrument of the intercolonial alliance until the US Constitution took effect eight years later. Of the forty-eight who signed it, twenty-two were lawyers.[5]

Third, the US Constitution was adopted in 1787 with the signatures of thirty-nine Constitutional Convention delegates, including an astonishing representation of twenty-one lawyers, amounting to more than half of the signers of this world-altering document.[6]

Between these three documents, each of which has so many lawyer-signers, there were surprisingly few duplicated lawyers. For example, neither John Adams nor Thomas Jefferson even attended the Constitutional Convention. In fact, of all the twenty-eight lawyer-signers of the Declaration, only four were also signers of the US Constitution, these being Roger Sherman, James Wilson, George Read, and John Rutledge. Only one lawyer, Roger Sherman, signed all three documents. Accordingly, the influence of lawyers was not confined to one small group of activists.

In his book The Founding Fathers on Leadership, Donald T. Phillips discusses the phenomenon of differing leadership skills coming forward at the right time and place during America’s struggle for independence. He states his theory thus: “At a most crucial moment in time, the great men now renowned as America’s founding fathers rose from the masses to lead the people of their homeland. They acted as a team—preparing for the Revolution, winning the war, and following through after victory was achieved. At appropriate times, when their individual skills, knowledge, and expertise were needed, some assumed the role of team leaders—then stepped back when another phase necessitated the need for others to be out in front.”[7] Consistent with Mr. Phillips’s theory, we see during the decades of the American chronicle a continual sequence of lawyer-founders rising to leadership or influence when their unique competencies became crucial to the cause.

Just after King George III succeeded to the throne in 1760, Parliament began to impose upon the colonies a new breed of taxes and regulations. Unpopular as they all were, it was the Stamp Act of 1765 that really stimulated a congealing of discontent. This act imposed a tax on just about every kind of paper product in the colonies. Understandably, this new levy on all legal and commercial documents stirred a particular umbrage within the legal community. The financial hit was particularly harsh. “By increasing the expense of lawsuits,” wrote John C. Miller, “the Stamp Act threatened to destroy the practice of colonial lawyers. Thus, at the outset of its quarrel with the colonies, the British government aroused the enmity of one of the most influential classes of men in America.”[8]

Before the Continental Congress or any other formal organization among the colonies existed, a Stamp Act Congress convened in opposition to this new tax burden. This event, the brainchild of Massachusetts lawyer James Otis, saw the first meeting of colonial delegates for a common cause in opposition to Britain. Of the twenty-seven colonial delegates in attendance, nearly a third (eight) were lawyers.[9] Those gathered elected another Massachusetts lawyer, Timothy Ruggles, as president of the assembly. John Dickinson, a lawyer delegate from Philadelphia, authored the document adopted by the congress in opposition to the Stamp Act, a “Declaration of Rights and Grievances.” As a result of the colonial outrage following this highly lawyered-up congress, the Stamp Act was repealed the next year.

The Continental Congress first convened in 1774 in response to the Intolerable Acts and continued until 1789, when the US Constitution took effect. During that period, fourteen men served as president of the Continental Congress (two served twice). Half of them were lawyers.[10]

Once the newly created United States government became operative, a surprising number of lawyers held many of the highest offices in the land. Of the first five presidents of the United States of America (1789–1825), all but George Washington were lawyers.[11] During the same period (1789–1825), of the six men who served as vice president, lawyers accounted for five.[12] Through the same years of 1789 through 1825, all eight of the first secretaries of state were lawyers.[13] The treasury secretaries numbered five out of seven.[14]

In addition to the official positions mentioned above, the following are but a few representative examples of notable lawyer contributions of a less formal nature. Samuel Adams co-founded the Sons of Liberty, a group of rogue patriot operatives known for the riotous Boston Tea Party and other clandestine activities that greatly fomented the spirit of revolution. His preponderant influence as an activist, through both tongue and quill, earned him the honorary title “Father of the Revolution.”[15]

In 1763, a brash young Virginia lawyer named Patrick Henry tried one of the first lawsuits to challenge the Crown’s authority in the colony. In a case called the “Parsons’ Cause,” what started out as a dispute over a piece of local legislation turned into a political flashpoint. As the established religion in Virginia, the Anglican Church clergy received their compensation from local taxes, payable in fixed poundage of tobacco. To avoid windfall compensation due to temporarily inflated tobacco prices, Virginia enacted a one-year measure to pay clergymen in currency based on a reduced market rate of the existing tobacco price. When King George vetoed the local law, the Reverend James Maury filed suit against Hanover County for back wages and Henry stood for the defense. Reverend Maury actually won the liability phase of the case, but with only a pyrrhic victory as the jury awarded him a single penny for damages—a classic case of winning a battle but losing the war.

More importantly, in Patrick Henry, the slow-rising schism between colony and Crown had truly found an explosive and passionate voice. In his courtroom description of the king, Henry drew a distinct line in the political sand: “A King, by disallowing Acts of this salutary nature, from being the father of his people, degenerated into a Tyrant and forfeits all right to his subjects’ obedience.”[16] Twelve years later, as Henry stood as a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, he made this memorable pronouncement that spoke to the hearts of his countrymen: “Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God!—I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”[17]

The adoption of Jefferson’s declaration on July 4, 1776, garners much credit as the seminal step toward independence. However, the official act of colonial separation, initiated by a fellow Virginia lawyer, had actually gained congressional approval two days prior to the Declaration of Independence.

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee, who later signed the Declaration of Independence, proposed to the Continental Congress what became known as the Lee Resolution, seconded by fellow lawyer John Adams. It contained the following text, the ratification of which would change the world: “Resolved: That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”[18]

Congress postponed the vote on the Lee Resolution to enable delegates to counsel with their respective colonies. In the interim and with the prospect of an affirmative vote, Congress commissioned the above-referenced committee of five to draft a declaration to King George so that it would be ready in the event the Lee Resolution ultimately passed.

In contemplation of Richard Henry Lee’s resolution, John Adams prophetically foresaw the consequences at stake. “Objects of the most stupendous magnitude, and measures in which the lives of millions yet unborn are intimately interested, are now before us. We are in the midst of a revolution, the most complete, unexpected and remarkable, of any in the history of nations.”[19]

The Continental Congress adopted the Lee Resolution on July 2, 1776. This vote marked the definitive act of dissolving the political ties with Britain. The Declaration of Independence, approved two days later, served as the letter to the king and Parliament pronouncing the separation and stating the offenses that compelled it.

The Federalist Papers were influential, groundbreaking essays about the US Constitution that effectively promoted its unanimous ratification by the colonies. Three lawyer-founders coauthored these momentous papers—Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison. These men also became the first secretary of state, the first chief justice of the US Supreme Court and the fourth president of the United States, respectively. For his superb leadership at the Constitutional Convention and as its principal draftsman, James Madison also earned the symbolic title “Father of the Constitution.” [20]

An interesting insight into the lawyer-founders comes from a historian who knew many of them firsthand. David Ramsay, MD (1749–1815), served both as a field surgeon during the war and as a delegate to the Continental Congress from South Carolina. He also survived the passing of two wives, one the daughter of a signer of the Declaration of Independence (Frances Witherspoon) and the other the daughter of one of the Continental Congress presidents (Martha Laurens). From this unique perspective, he authored his two-volume set The History of the American Revolution, first printed in 1789. His philosophical impressions provide perhaps a glimpse as to why the Lord saw the need to add legal skills to the mix of Founding Father talents: “No order of men has, in all ages, been more favourable to liberty, than lawyers. Where they are not won over to the service of government, they are formidable adversaries to it. Professionally taught the rights of human nature, they keenly and quickly perceive every attack made on them. While others judge of bad principles by the actual grievances they occasion, lawyers discover them at a distance, and trace future mischiefs from gilded innovations.”[21]

Two hundred years after the publication of Dr. Ramsay’s history, Kenneth W. Starr, former solicitor general of the United States, added his personal view on the lawyer-founders and the coming forth of the US Constitution, the crown jewel of the Revolution. In his speech at the convocation of the J. Reuben Clark Law School on April 27, 1990, he said, “They were great men at the convention, and some of the greatest were not lawyers. But when one examines the records of that convention, one quickly discovers that the intellectual leaders—the true shapers of our government—were lawyers. From Madison and Randolph of Virginia, to Wilson of Pennsylvania, Elsworth of Connecticut, and Paterson of New Jersey, these were individuals who had been called to the bar.”[22]

Nothing should be inferred from the foregoing that lawyers carried all or even most of the water in the long quest for independence and self-government. The wisdom and courage that prevailed were certainly not confined to members of the bar. Where a seemingly impressive one-third of a body of delegates happened to be lawyers, clearly, two-thirds were not. Among the Founding Fathers, we see a spectrum of occupations such as farmers, merchants, ministers, bankers, physicians, and tradesmen. Without the business acumen of a John Hancock, the wit and wisdom of a Ben Franklin, or the spirituality of a Reverend Witherspoon, all the lawyers combined would likely not have accomplished alone the whole of what the Lord intended for this land. The miracle of the American story resulted from the diverse talents and thinking of all the Founding Fathers whom the Lord inspired for that purpose.

The diversity of the Founding Fathers notwithstanding, the statistical relevance of the relatively few lawyers in relation to the colonial population as a whole is worthy of note as a historical fact. The non-slave population within the thirteen colonies in 1776 approximated two million. By comparison, the number of colonial lawyers hardly scored a blip on the radar.

Insufficient data prevents a fully accurate count of colonial lawyers at any particular point. In his renowned account of early American law and lawyers, History of the American Bar, first published in 1911, Charles Warren includes a few numbers from which we can glean the clear minority status of colonial lawyers. With respect to the Virginia Bar, he states, “Between the years 1750 and 1775, there was a marked growth in the size and ability of the Virginia Bar.”[23] Without stating that these were the only Virginia lawyers, Mr. Warren mentions just sixteen names. With respect to the Massachusetts bar, Warren says, “By 1768, the order of barristers was so well recognized that it is known that there were then twenty-five.”[24] And for New York he notes, “Valentine, in his History of the City of New York, gives a list of only forty-one lawyers practising in the city between 1695 and 1769.”[25] As for South Carolina he adds, “In 1761, at the time when John Rutledge, the earliest of South Carolina’s lawyers, began to practise, the Bar consisted of probably not more than twenty, and prior to the Revolution no more than fifty-eight had been admitted to practise.”[26]

Considering this scant information from four of the most prominent bars in the colonies, a legitimate inference may be drawn that the relative percentage of lawyers in the colonial population would be very small. In fact, with a population of two million, it would take twenty thousand lawyers to amount to even one percent! Thus, in a tally of who’s who among the Founding Fathers, the lawyer-founders played a comparatively significant role. It should also be noted, however, that within the colonial-lawyer population, not all stood in lockstep agreement with independence. Unlike those patriot-lawyers described above, many of the colonial lawyers remained steadfast in their loyalty to Britain and were not part of this movement to prepare the land for the Restoration.

The Eighteenth-Century Evolution of the Colonial Lawyer

Through the first half of the eighteenth century, it would not appear that lawyers would be playing such prominent roles in the coming events. Their status as leaders would of necessity have required a level of social trust and prestige that they did not enjoy in the early 1700s. However, at that critical time when their collective skills and influence came to bear, their community standing had rapidly changed.

Warren explains the social and commercial factors affecting the standing of colonial lawyers at that time:

With the beginning of the Eighteenth Century, however, a new set of factors began to work to produce the American Bar, which soon counteracted the old retarding influences. . . .

Means of education increased. . . .

There was, at the same time, a very rapid extension of commerce, of export trade, of shipbuilding, fisheries and slavetrading. A class of rich merchants began to control in the community. Questions as to business contracts and business paper began to rise. . . . The political liberties guaranteed by the principles of the English Common Law became increasingly more vital to the colonists, as the Royal Governors attempted to enlarge their own powers, and the King and Parliament began to trespass on what the Colonies regarded as their own prerogatives.[27]

He concludes:

And so arose the need for lawyers versed in law as a science…

And it was this superior education and training which befitted the lawyer of the Eighteenth Century to become the spokesman, the writer and the orator of the people when the people were forced to look for champions against the pretensions of the Royal Governors and judges and of the British Parliament. So that when the War of the Revolution broke out, the lawyer, from being an object of contempt . . . had become the leading man in every town in the country, taking rank with the parish clergyman and the family doctor.[28]

This same point had been urged earlier by a Massachusetts lawyer and frequent contributor to the Atlantic Monthly on topics of colonial law and politics. In an article published in 1889, Frank Gaylord Cook wrote, “From the middle of the eighteenth century to the Revolution, politics more and more employed the services of the legal profession; and for this work they were well fitted by their broad experience in affairs and by their simple but vigorous discipline. The standard for admission to the bar had everywhere been raised.”[29]

Symbolic Contributions

Much more could be written of lawyer-founders in the substantive making of America, both nationally as well as within the local colonial governments. Ironically, perhaps the two most important symbols of America also came from lawyers. While American folklore attributes the sewing of the first American flag to Betsy Ross, Francis Hopkinson, a New Jersey lawyer and signer of the Declaration of Independence, takes credit as the actual designer of the first Stars and Stripes. And while a New York lawyer sat captive aboard a British vessel during the War of 1812, he watched the relatively new Congreve rockets flashing through the night sky over Chesapeake Bay with their arcs of red flame. As morning dawned and he saw the flag at Fort McHenry still waving, Francis Scott Key jotted on the back of an envelope the first words that would later become our national anthem.

The Making of a Colonial Lawyer

Christopher C. Langdell, dean of the Harvard Law School from 1870 to 1895, described the objective of a legal education thus: “Law, considered as a science, consists of certain principles or doctrines. To have such a mastery of these as to be able to apply them with constant facility and certainty to the ever-tangled skein of human affairs, is what constitutes a true lawyer; and hence to acquire that mastery should be the business of every earnest student of the law.”[30]

The requirements of becoming a colonial lawyer, they certainly did not rise to the level that contemporary law school students face, but the objectives were the same. And while perhaps less strict than today’s standards, there were some fairly recognizable procedures for regulating the practice of law. By the time of the Revolutionary War, each of the thirteen colonies exercised some level of control over the practice of law, and most had actual bar admission requirements. For example, Massachusetts passed a statute in 1701 providing for the licensing of all lawyers as well as a form of oath to be taken. Virginia passed a similar statute in 1748. In New York the first law licenses were issued by the governor in 1709. Representative of the deeper south, South Carolina’s statute for admission to practice in court was passed in 1721.

The first lawyers on American shores imported their legal educations from England. Since the Middle Ages, legal education in Britain had been the province of the Inns of Court. Not exactly colleges or universities, these were societies where students could take residence and receive their legal training. Several of the lawyer-founders learned their trade at one of the British Inns of Court, just as many of the sons from wealthy colonial families also received their general educations in British schools.

In colonial America there were no Inns of Court. An alternative method of legal education developed, in which a student paid a standing member of the bar for mentoring. This also required the rigorous study of the relatively few law books available in America. In some cases, lawyers became certified to practice with only a thorough personal study on their own. Such was the case with the brilliant orator and trial lawyer Patrick Henry.

Law books were scarce in colonial America and most came from British publishers. By 1776, only a few law books were printed in America, as well as the proceedings of a few significant court cases. Some of the more common books found in colonial-lawyer libraries included Coke on Littleton, Comyn’s Digest, Bacon’s Abridgment, and Hale’s or Hawkins’s Pleas of the Crown.

It we accept that the Lord had a purpose in raising up these many lawyers as leaders in the American cause, then perhaps it follows that Sir William Blackstone himself my have been one of those wise men. Sir William Blackstone, Unknown Artist, National Portrait Gallery, London

It we accept that the Lord had a purpose in raising up these many lawyers as leaders in the American cause, then perhaps it follows that Sir William Blackstone himself my have been one of those wise men. Sir William Blackstone, Unknown Artist, National Portrait Gallery, London

Interestingly, with the increased need for more competent counsel in the mid-1700s, as described by Warren, came the printing of a new set of law books adding to the rapid evolution of the colonial lawyer. This four-volume set, entitled Blackstone’s Commentaries, was published in England between 1765 and 1769. Consider Warren’s reasoning on the impact of this new treatise: “It was the advent of Blackstone which opened the eyes of American scholars to the broader field of learning in the law. He taught them, for the first time, the continuity, the unity, and the reason of the Common Law—and just at a time when the need of a unified system both in law and politics was beginning to be felt in the Colonies.”[31]

Even though rising numbers of would-be lawyers may have been intrigued by the opportunities of a growing colonial economy, at least one prominent historian saw an accompanying altruism in their collective preparations. The late Page Smith, professor emeritus of history, observed in one of his more than twenty books that many colonial lawyers exhibited a sense of a greater purpose in preparing themselves for the exigencies of the day:

It was not simply their reading—law, history, political and moral philosophy—that made the colonial lawyers the most learned men of their age, the most scholarly statesmen in the history of this or any other republic; it was the context in which their reading took place. The generation of revolutionary lawyers read with a special intensity; they searched through all the wisdom of the past to find a formula in the name of which the liberties of all Englishmen might be preserved. . . . Like schoolboys cramming for an examination, they devoured every book they could get their hands on that seemed to speak to their own particular situation. They gained, thereby, a vast access of power; they stepped forward, often quite self-consciously, to take a place in that same history of which they were such assiduous students, and in so doing they shed, almost casually, the limitations and inhibitions of provincials, of haphazardly trained and indifferently schooled colonials, and appeared as men able to hold their own intellectually in any company.[32]

In summary, in the mid-1700s, commercial, intellectual, and social changes were afoot amongst the colonial lawyers and their communities, creating opportunity to put strategically capable people in the right place and at the right time to advance the work of the Revolution in preparation for the Restoration that would follow.

Higher Education in Colonial America

In The Americans: The Colonial Experience, Daniel J. Boorstin, noted American history professor, librarian of Congress, prolific author, and attorney explained that while Britain was limited to only two legally authorized universities, Oxford and Cambridge, higher education had become a much more extensive pursuit in America. Although the thirteen colonies were all subjects of the same British sovereign, they still developed and operated independently one from another. Before the era of the Revolution, there was no sense of nationalism that would foster institutions of higher learning for the benefit of the colonies as a whole. And since the colonial authority to create such educational institutions was at best unclear and at worst illegal, the colonies relied on the old adage that it is easier to obtain forgiveness than permission in developing their own regional institutions of higher learning. These were mostly instituted by the various religions of the day.

By the time of the Revolution, Harvard, Yale, the College of William and Mary, New Jersey College (later Princeton University), Rhode Island College (later Brown University), Rutgers, Dartmouth, King’s College (later Columbia University), and the College of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania) were all in the business of granting degrees, even though most lacked any authorization to do so from the Motherland.

Not only were American colleges more numerous than Britain’s, but they also operated from a different perspective, as Boorstin explained:

The primary aim of the American college was not to increase the continental stock of cultivated men, but rather to supply its particular region with knowledgeable ministers, lawyers, doctors, merchants, and political leaders. . . .

In England, the leading families sent their sons away to the few best “public” schools, and afterwards these young gentlemen were gathered—-if only for hunting and wassailing—at Oxford and Cambridge. . . .

No American who could afford the fee of ten pounds a year for four years could fail to secure, if he wanted it, the hallmark of a “higher” education. American colleges were not just distributing to the many what in England was reserved for the privileged few; they were issuing an inflated intellectual currency. . . .

American colleges, in contrast to England, were more anxious to spread than to deepen higher learning.[33]

In summary, as opposed to Britain, higher education in the colonies was more broadly dispersed and more practical than traditional.

Concurrent with this American notion of extending higher education to the common man, there also arose a widespread interest in gaining a familiarity with the law, meaning the English common law upon which most of colonial jurisprudence was based. Boorstin noted: “If the American lawyer sometimes possessed less legal learning than his English counterpart, the literate American layman possessed more of it. . . . Needless to say, colonial America produced no great legal systems or encyclopaedias. What it did produce were the varied, dispersed, and miscellaneous efforts of hundreds of laymen, semi-lawyers, pseudo-lawyers, and a few men of solid legal learning.”[34]

The English statesman Edmund Burke made this same observation in his famous 1775 speech to the House of Commons in urging reconciliation with the colonies. “In no country perhaps in the world is the law so general a study. The profession itself is numerous and powerful; and in most provinces it takes the lead. The greater number of the deputies sent to the Congress were lawyers. But all who read, and most do read, endeavor to obtain some smattering in that science.”[35]

Blackstone’s Commentaries, the treatise that greatly facilitated the legal education of colonial lawyers, had a similar impact on many curious-minded laymen as well. Boorstin described the influence of Blackstone not only on those who sought to become lawyers but also on those who wished merely to familiarize themselves with the basics of law. “Blackstone was a godsend to the rising American, to the ambitious backwoodsman and the aspiring politician. One of the delightful ironies of American history is that a snobbish Tory barrister, who had polished his periods to suit the tastes of young Oxford gentlemen, became the mentor of Abe Lincoln and thousands like him. By making legal ideas and legal jargon accessible in the backwoods, Blackstone did much to prepare self-made men for leadership in the New World.”[36]

If we accept as true that the Lord had a purpose in raising up these many lawyers as leaders in the American cause, then perhaps it follows that Sir William Blackstone himself, by virtue of his unique and timely contribution to the legal education of both patriot-lawyers and laymen, may have also been one of those “wise men” described by the Lord in Doctrine and Covenants 101:80.

This notion of such a broad understanding of law among the colonial populace raises an interesting point with respect to the phenomenon of so many colonial lawyers being elected to leadership. It may have been more than mere chance or blind ignorance on the part of the voting public. With such a widely dispersed interest in and understanding of the law among the population, colonial voters in general may have intentionally selected so many lawyer-delegates based on at least some awareness of what they were likely getting in such legally trained representatives. In other words, it may have been the result of what lawyers often refer to as informed consent. And perhaps this too was wrought by the hand of the Lord.

A Poetic Historical Ending

In 1826, John Adams, age ninety, and Thomas Jefferson, eight- three, being two of only three remaining signers of the Declaration of Independence, were invited to attend Fourth of July celebrations in Boston and Washington DC, respectively. Each declined due to failing health. During the latter years of their retirement, the baton of leadership having long since passed to younger men, Adams and Jefferson reconciled the deep and personal differences that had separated them during the early years of the new government. Having buried the hatchet, they engaged in a most tender and enduring correspondence for the rest of their lives. On that very July Fourth, being the fiftieth anniversary of their declaration, Adams and Jefferson each passed quietly into history. Adams uttered his final words, “Thomas Jefferson still survives.”[37] He did not have the benefit of phone, fax, or CNN from which to learn that Jefferson had shortly preceded him in death.

The significance of these simultaneous deaths on that date was not lost on a grateful citizenry. The Albany Argus and City Gazette published an obituary just six days later:

No common event has clothed our columns in the habiliments of mourning. Two of the great and gifted of our countrymen, the venerated fathers of our Republic, THOMAS JEFFERSON and JOHN ADAMS, are no more! It is not amongst the least of the events so wisely ordered in the progress of this country, that the Author of the Declaration of its Liberties, and his eminent associate in that duty, should be permitted not only to live, and to witness the prosperous experiment of half a century, but that on that day fifty years on which they signed and issued their Declaration to the world, they should be called, both together, from amongst a people so signally blessed by their labours. They were glorious in their lives, and in their deaths they were not divided. They have enjoyed in their life-time equal and the highest honours within the gift of a grateful country. In their deaths, the measure of their fame is full. Their memories are hallowed.[38]

Some may think it a mere coincidence. Others may call it heaven’s way of putting an exclamation point on the miracle of the Revolution. Either way, surely none would disagree that the death of these two particular signers on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence was an epic event. Both Adams and Jefferson, over their long lifetimes, had undeniably given their lives and their fortunes to their country, and in so doing they consecrated that sacred oath made long before when they were brave young lawyers.

Neither Adams nor Jefferson had likely known that just six years prior to their passing, the heavens had again opened and a fourteen-year-old boy had been called to restore all things within a country they were so instrumental in creating. The only other surviving signer of the Declaration lived another six years—Charles Carroll, a Maryland lawyer and ardent revolutionary who lived two years beyond the restoration of the Church of Jesus Christ in 1830. It seems poetic that these three would tarry long enough as representatives of their noble colleagues, and perhaps even as honored sentinels, to be present on Earth for the ushering in of those crucial events which their selfless service had helped to make possible.

The Faith of the Lawyer-Founders

In 1877, Wilford Woodruff, then serving as president of the St. George Temple, experienced a sacred visitation. He later testified:

I will say here, before closing, that two weeks before I left St. George, the spirits of the dead gathered around me, wanting to know why we did not redeem them. Said they, “You have had the use of the Endowment House for a number of years, and yet nothing has ever been done for us. We laid the foundation of the government you now enjoy, and we never apostatized from it, but we remained true to it and were faithful to God.” These were the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and they waited on me for two days and two nights. . . . I straightway went into the baptismal font and called upon brother McCallister to baptize me for the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and fifty other eminent men, making one hundred in all, including John Wesley, Columbus, and others; I then baptized him for every President of the United States, except three; and when their cause is just, somebody will do the work for them.[39]

One of those deceased participants in this sacred visitation, while yet in life, declared his belief in an eternal doctrine which had not yet been fully revealed in his day, a doctrinal blessing to which he later made claim at the hands of President Woodruff in the St. George Temple. Following the death of his beloved companion, Abigail, in 1818, John Adams expressed his tender feelings in a letter to his old friend, Thomas Jefferson:

I know not how to prove physically, that we shall meet and know each other in a future state; nor does Revelation as I can find, give us any positive assurance of such a felicity. . . . I believe in God and in his wisdom and benevolence; and I cannot conceive that such a being could make such a species as the human, merely to live and die on this earth. If I did not believe in a future state, I should believe in no God. . . . And if there be a future state, why should the Almighty dissolve forever all the tender ties which unite us so delightfully in this world, and forbid us to see each other in the next?[40]

The artist John Trumbull depicts the presentation of the Declaration of Independence to Congress for approval and signing. John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence

The artist John Trumbull depicts the presentation of the Declaration of Independence to Congress for approval and signing. John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence

This temple service performed by President Woodruff and Brother McCallister on behalf of the Founding Fathers and “other eminent men” included many lawyer-founders. There were at least twenty-eight lawyers among the fifty-six Declaration signers. Of the fifteen US presidents who were vicariously baptized, ten were lawyers, noting that John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were both Declaration-signers and US presidents.[41] Any description of President Woodruff’s experience in the St. George Temple should not omit the fact that in conjunction with the vicarious baptisms of these men, Brigham Young’s wife Lucy Bigelow Young stood as proxy for the baptisms of approximately seventy “eminent women,” some of whom were wives of Founding Fathers, including Martha Washington (George), Abigail Adams (John), Dolly Madison (James) and Sarah Jay (John).[42]

Wilford Woodruff spoke reflectively of the character of these Founding Fathers at the April 1898 general conference, saying, “Those men who laid the foundation of this American government and signed the Declaration of Independence were the best spirits the God of heaven could find on the face of the earth. They were choice spirits, not wicked men. General Washington and all the men that labored for the purpose were inspired of the Lord.”[43] In the April 1957 general conference, President J. Reuben Clark Jr. concurred: “There has not been another such group of men in all the . . . years of our history, no group that even challenged the supremacy of this group.”[44]

In their own words, many lawyer-founders publicly pronounced their faith in God as the moral compass of their lives. And some had specific feelings about the divine origin of what they created. These are a few representative examples:

Thomas Jefferson: “The God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time.”[45]

Samuel Adams: “Revelation assures us that ‘Righteousness exalteth a Nation’—Communities are dealt with in this World by the wise and just Ruler of the Universe. He rewards or punishes them according to their general character.”[46]

John Jay: “We should always remember, that the many remarkable and unexpected means and events by which our wants have been supplied, and our enemies repelled or restrained, are such strong and striking proofs of the interposition of Heaven, that our having been delivered from the threatened bondage of Britain, ought, like the emancipation of the Jews from Egyptian servitude, be forever ascribed to its true cause, and instead of swelling our breasts with arrogant ideas of our power and importance, kindle in them a flame of gratitude and piety, which may consume all remains of vice and irreligion. Blessed be God.”[47]

Alexander Hamilton: “For my own part, I sincerely esteem it a system, which, without the finger of God, never could have been suggested and agreed upon by such a diversity of interests.”[48]

Charles Pinckney: “When the great work was done and published, I was . . . struck with amazement. Nothing less than that superintending hand of Providence, that so miraculously carried us through the war . . . , could have brought it about so complete, upon the whole.”[49]

Patrick Henry: “There is a just God who presides over the destinies of nations and who will raise up friends to fight our battles for us.”[50]

James Madison: “It is impossible for the man of pious reflection not to perceive in it a finger of that Almighty hand which has been so frequently and signally extended to our relief in the critical stages of the revolution.”[51]

Conclusion

These lawyer-founders, like their fellow Founding Fathers and other similarly inspired individuals, willingly performed the unique roles for which they were prepared and moved to accomplish. When the time ripened for a religious awakening, the Lord inspired the likes of John Calvin, a trained lawyer turned theologian. To reveal the Americas to the world, the Holy Ghost touched the heart of a courageous explorer. And at that moment in history when the Lord’s timetable called for their particular talents, there stood ready and willing a group of colonial lawyers with minds trained in law and politics, rooted in judgment and wisdom, which surely numbered them among the inspired Founding Fathers.

Notes

[1] Andrew C. Skinner, “Forerunners and Foundation Stones of the Restoration,” in Prelude to the Restoration: From Apostasy to the Restored Church (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2004), 14.

[2] Historians disagree as to who were actually colonial lawyers in a technical sense. Due in part to the less ceremonial manner in which most acquired their legal education, identifying them is not an exact science, as some subjectivity may be involved. For example, of the number of lawyer-signers of the Declaration of Independence, Matthew Spaulding of the Heritage Foundation states that they were twenty-two, while Richard B. Morris, former Columbia history professor and president of the American Historical Association, states that at least thirty had legal training. President Ezra Taft Benson takes a middle road and says there were twenty-three lawyer-signers. See note 20. While these authors do not name names, they apparently each provided numbers based on whatever information they deemed reliable, as has this author in determining who to include as colonial lawyers.

Perhaps the most notable of these lawyer-founders whose credentials may be questioned is Samuel Adams, who is not universally referred to as a lawyer. Several historians record that following his master’s degree from Harvard, Adams pursued legal studies at the urging of his father and that at some unknown point in the process, his mother dissuaded him from that profession. Most of these omit mentioning how much of a legal education he pursued. Noted historian of colonial law and lawyers Charles Warren provides the clearest evidence by affirmatively stating that Samuel Adams had become a member of the Massachusetts Bar. See 82 n. 23. At least one other source, John C. Fredriksen’s Revolutionary War Almanac (New York: Facts on File, 2006), refers to law as one of Sam Adams’s failed businesses.

Those referred to herein have each been confirmed as a lawyer, as defined above, through at least two published sources, with the exception of a handful for whom only one noted publication has been relied upon. As referred to herein, the descriptions of “lawyer” and “member of the bar” are used interchangeably.

[3] Lawyer-signers of the Declaration of Independence (alphabetically): John Adams (MA), Samuel Adams (MA), Charles Carroll (MD), Samuel Chase (MD), William Ellery (RI), Thomas Heyward Jr. (SC), William Hooper (NC), Francis Hopkinson (NJ), Samuel Huntington (CT), Thomas Jefferson (VA), Richard Henry Lee (VA), Thomas Lynch Jr. (SC), Thomas McKean (DE), Arthur Middleton (SC), William Paca (MD), Robert Treat Paine (MA), John Penn (NC), George Read (DE), George Ross (PA), Edward Rutledge (SC), Roger Sherman (CT), James Smith (PA), Richard Stockton (NJ), Thomas Stone (MD), George Walton (GA), James Wilson (PA), Oliver Wolcott Sr. (CT), and George Wythe (VA).

[4] David C. Whitney and others, Founders of Freedom in America (Chicago: J. G. Ferguson, 1973), 20.

[5] Lawyer-signers of the Articles of Confederation (alphabetically): Andrew Adams (CT), Samuel Adams (MA), John Banister (VA), Francis Dana (MA), John Dickinson (DE), William H. Drayton (SC), James Duane (NY), William Ellery (RI), John Harvie (VA), Thomas Heyward Jr. (SC), Titus Hosmer (CT), Samuel Huntington (CT), Richard Hutson (SC), Henry Marchant (RI), John Mathews (SC), Thomas McKean (DE), Gouverneur Morris (NY), John Penn (NC), Joseph Reed (PA), Roger Sherman (CT), Nicholas Van Dyke (DE), and John Wentworth Jr. (NH).

[6] Lawyer-signers of the US Constitution (alphabetically): Abraham Baldwin (GA), Richard Bassett (DE), Gunning Bedford Jr. (DE), John Blair (VA), David Brearley (NJ), Jonathan Dayton (NJ), John Dickinson (DE), William Few (GA), Alexander Hamilton (NY), Jared Ingersoll (PA), William S. Johnson (CT), Rufus King (MA), William Livingston (NJ), James Madison (VA), Gouverneur Morris (PA), William Paterson (NJ), Charles C. Pinckney (SC), George Read (DE), John Rutledge (SC), Roger Sherman (CT), and James Wilson (PA).

[7] Donald T. Phillips, The Founding Fathers on Leadership (New York: Warner Books, 1997), 12.

[8] John C. Miller, Sam Adams: Pioneer in Propaganda (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1936), 55.

[9] Lawyer-delegates to the Stamp Act Congress of 1765 (alphabetically): John Dickinson (PA), Eliphalet Dyer (CT), William S. Johnson (CT), Robert R. Livingston Sr. (NY), Thomas McKean (DE), James Otis (MA), Timothy Ruggles (MA), and John Rutledge (SC).

[10] Lawyer-presidents of the Continental Congress (in order of service): Peyton Randolph, John Jay, Samuel Huntington, Thomas McKean, Elias Boudinot, Richard Henry Lee, and Cyrus Griffin.

[11] The first four lawyer-presidents of the United States of America (in order of service): John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe.

[12] The first five lawyer–vice presidents of the United States of America (in order of service): John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Aaron Burr, George Clinton and Daniel D. Tompkins.

[13] The first eight lawyer–secretaries of state (in order of service): Thomas Jefferson, Edmund Randolph, Timothy Pickering, John Marshall, James Madison, Robert Smith, James Monroe, and John Quincy Adams.

[14] The first five lawyer–secretaries of treasury (in order of service): Alexander Hamilton, Oliver Wolcott Jr., Samuel Dexter, Alexander J. Dallas, and William H. Crawford.

[15] Mark D. Puls, Samuel Adams: Father of the American Revolution (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

[16] David A. McCants, Patrick Henry, the Orator (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1990), 118.

[17] McCants, Patrick Henry, 125.

[18] Whitney, Founders of Freedom, 19.

[19] Whitney, Founders of Freedom, 19.

[20] Ezra Taft Benson, This Nation Shall Endure (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1979), 18.

[21] David Ramsay, The History of the American Revolution, ed. Lester H. Cohen (Philadelphia: R. Aitken, 1789; Indianapolis: Liberty Classics, 1990), 1:29.

[22] Kenneth W. Starr, “Acquired by Character Not by Money,” Clark Memorandum, fall 1990, 9.

[23] Charles Warren, A History of the American Bar (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1911; Washington DC: Beard Books, 1999), 46.

[24] Warren, History of the American Bar, 87.

[25] Warren, History of the American Bar, 96.

[26] Warren, History of the American Bar, 121.

[27] Warren, History of the American Bar, 16–17.

[28] Warren, History of the American Bar, 17–18.

[29] Frank Gaylord Cook, “Some Colonial Lawyers and Their Work,” Atlantic Monthly, March 1889, 374.

[30] Quoted in Steve Sheppard, ed., The History of Legal Education in the United States, vol. 1, Commentaries and Primary Sources (Pasadena, CA: Salem Press, 1999), 27.

[31] Warren, History of the American Bar, 177.

[32] Page Smith, A People’s History of the American Revolution: A New Age Now Begins, (New York: McGraw Hill, 1976), 1: 256.

[33] Daniel J. Boorstin, The Americans: The Colonial Experience (London: Phoenix Press, 1958), 181–184.

[34] Boorstin, The Americans, 201.

[35] Edmund Burke, Speech on Conciliation with America, March 22, 1775; http://

[36] Boorstin, The Americans, 37.

[37] Whitney, Founders of Freedom in America, 44.

[38] The Albany (NY)Argus & City Gazette, July 10, 1826.

[39] Wilford Woodruff, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-Day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 19:229.

[40] Alf J. Mapp Jr., The Faith of Our Fathers (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 63.

[41] The fifteen U.S. presidents for whom D. T. McCallister was vicariously baptized (in order of service): George Washington, lawyer John Adams, lawyer Thomas Jefferson, lawyer James Madison, lawyer James Monroe, lawyer John Quincy Adams, lawyer Andrew Jackson, William Henry Harrison, lawyer John Tyler, lawyer James K. Polk, Zachery Taylor, lawyer Millard Fillmore, lawyer Franklin Pierce, lawyer Abraham Lincoln, and Andrew Johnson.

[42] Vicki Jo Anderson, The Other Eminent Men of Wilford Woodruff (Malta, ID: Nelson Book, 1994), 419–420. Although Anderson quotes Elder Woodruff’s journal that the work for seventy women was performed, she lists the names of only sixty-eight. See 411–418.

[43] Wilford Woodruff, in Conference Report, April 1898, 89–90.

[44] J. Reuben Clark Jr., in Conference Report, April 1957, 47.

[45] Thomas Jefferson, “A Summary View of the Rights of British America” (1774), quoted in Benson, This Nation Shall Endure, 130.

[46] The Writings of Samuel Adams, vol. 3, 1773–1777, ed. Harry Alonzo Cushing, (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1907), 286.

[47] William Jay, The Life of John Jay, with Selections from His Correspondence and Miscellaneous Papers (New York: J. & J. Harper, 1833), 1:81; emphasis in original.

[48] E. H. Scott, ed., The Federalist and Other Contemporary Papers on the Constitution of the United States, (Chicago: Scott, Foresman, 1894), 646.

[49] P. L. Ford, ed., Essays on the Constitution (1892), 412, quoted in Benson, This Nation Shall Endure, 18.

[50] Patrick Henry, address to the Convention of Delegates of Virginia, March 23, 1775, quoted in Benson, This Nation Shall Endure, 85.

[51] James Madison, Federalist, no. 37, quoted in Benson, This Nation Shall Endure, 18–19.