Icebergs, Point Guards, Waves, and Softballs: The Power of Good Questions and Discussions

Steven T Linford

Steven T. Linford, "Icebergs, Point Guards, Waves, and Softballs: The Power of Good Questions and Discussions," Religious Educator 12, no.1 (2011): 127–149.

Steven T. Linford (linfordst@ldschurch.org) was a preservice trainer in the Seminary Teacher Training Office at BYU when this was written.

Icebergs, point guards, waves, and softballs are analogies that aid teachers in asking good questions and directing effective discussions to encourage meaningful participation. Matt Reier, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Icebergs, point guards, waves, and softballs are analogies that aid teachers in asking good questions and directing effective discussions to encourage meaningful participation. Matt Reier, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

What do icebergs, point guards, waves, and softballs have to do with asking good questions and directing effective discussions? They are analogies that can help teachers ask better questions and direct more insightful and inspiring discussions. These analogies will be presented along with principles and practices that can help teachers. The Teaching the Gospel handbook states, “Effective teaching is edifying teaching, and people are more likely to be edified when they participate in learning under the influence of the Spirit. . . . Asking good questions and directing effective discussions are primary ways to encourage that participation.”[1]

If asking good questions and directing effective discussions are primary ways to encourage meaningful participation, then what constitutes a good question? Teaching the Gospel suggests that teachers should “ask questions that stimulate thinking and encourage student response. Questions can be asked that lead students to search for information, analyze what they are studying, or help them apply it in their own lives.” Furthermore it suggests, “Teachers should avoid questions that can be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or where the answer is so obvious the students are not motivated to think about it.” It also adds, “Good questions require students to search the scriptures for the answer and to seek the Spirit’s help.” According to this handbook, good questions “ask students to apply what they have learned from the verses,” draw comparisons of “a person or an event in one part of the scriptures to another person or event somewhere else.” In sum, “Good questions are the very heart of good discussions.”[2]

Elder Richard G. Scott stated, “It is imperative that we use our every capacity to stimulate students to think.” He continued, “Ask carefully formulated questions that stimulate thought. Even if the responses are not perfect, they will increase the probability that important lessons will be learned.”[3] As students respond to questions and share what they think, they are much more likely to retain the lessons that are being discussed. Furthermore, as they verbally participate, the lesson is retained longer in the storage of their mind. Most importantly, by sharing what they know and feel, students can have their words driven deep into their hearts by the Holy Ghost.

In addressing the importance of asking good questions, President Henry B. Eyring gave the following counsel:

Now, I suggest one more routine tool that we might use more effectively: to ask and to answer questions is at the heart of all learning and all teaching. . . . Some of those questions require only an answer of fact taken from memory: “Who was the father of Helaman?” or “Unto whom is this land consecrated?”

But some questions invite inspiration. Great teachers ask those. That may take just a small change of words, an inflection in the voice. Here is a question that might not invite inspiration: “How is a true prophet recognized?” That question invites an answer which is a list, drawn from memory of the scriptures and the words of living prophets. Many students could participate in answering. Most could give at least a passable suggestion. And minds would be stimulated.

But we could also ask the question this way, with just a small difference: “When have you felt that you were in the presence of a prophet?” That will invite individuals to search their memories for feelings. After asking, we might wisely wait for a moment before calling on someone to respond. Even those who do not speak will be thinking of spiritual experiences. That will invite the Holy Ghost. Then, even if no one should speak, they will be ready for you to bear quiet testimony of your witness that we are blessed to live when God has called prophets to guide and teach us.[4]

In speaking of the importance of asking good questions, Chad H. Webb, administrator of Seminaries and Institutes, stated, “Another teaching practice that is crucial to inviting the Spirit is to ask good questions. This is especially true with questions that cause our students to think about their experiences with gospel principles or that cause them to reply with testimony. Questions like ‘When have you been blessed by being obedient to that commandment?’ or ‘Why do you believe that principle is true?’ will often cause our students to respond by expressing their gratitude to the Lord and their testimonies of gospel principles. Good questions are simple yet powerful ways to invite the Holy Ghost to witness to our students.”[5]

The following is a list of questions that, when asked, can provide an opportunity for students to “search their memory for feelings” and to “express their gratitude to the Lord and their testimonies of gospel principles”:

- When have you seen, felt, or experienced this principle in your life?

- What difference has this principle made in your life?

- How has living this principle helped you (or someone you know)?

- What evidence have you seen in your life that this principle is true?

- When have you been blessed by being obedient to this commandment?

- How do you know that what we have talked about is true?

- Why is this meaningful to you? Why is this important to you?

- How has knowing this principle helped you in your life?

- Why do you believe this principle is true?

- Would you explain how understanding this principle makes you feel gratitude for the Lord?

Certain types of questions can help students share positive examples of people they know who are living the discussed principle. By having students share examples of those they personally know who live the principle with excellence, students will feel the Spirit and hopefully receive encouragement to more fully live that truth. Most importantly, these questions can help students consider how they can better influence or serve other people, especially family members, as they more fully apply and live gospel principles.[6] Note the following examples of questions that assist students in sharing and applying the positive qualities of people they know:

- Do you know anyone who exemplifies this principle?

- Do you know anyone in your family, among your friends, or at your school who is an excellent example of living this principle?

- What did you learn from the example of (Nephi) that you could apply to your own life?

- Why is this principle important and critical in your life right now?

- How will living this principle help you to strengthen your family?

Students seem to enjoy speaking about those they know who are great examples, especially friends, classmates, leaders, and parents. As students discuss these testimony-fortifying examples, they are often edified, especially as we connect them to the perfect life of the Savior. Furthermore, seeing positive examples of others living the gospel can help students “more easily understand how gospel principles can be applied in their own lives.”[7] As we apply truth, we are prone to make the vital choices in our life in accordance with our Heavenly Father’s will.

“Appropriate questions,” according to Elder Scott, “lead a student to think about doctrine, appreciate it, and understand how to apply it in his or her personal life.”[8] In addition, the Teaching and Learning Emphasis, which gives direction to seminary and institute teachers and leaders, adds, “Applying gospel principles brings promised blessings, deepens understanding and conversion, and helps us become more like the Savior.”[9] Nephi also shared benefits of applying gospel principles when he said he “did liken all scriptures unto us that it might be for our profit, and learning, . . . that [we] might have hope” (1 Nephi 19:23–24).

The following types of questions, when utilized, provide an opportunity for students to share how they have come to know a principle is true, and to help those who are struggling to understand, accept, or live a principle. As students hear their classmates bearing testimony of what they know is true, as well as how they came to know it, a seed can be planted in the hearts of the listeners, which can “begin to swell,” “enlarge [their] soul,” and “enlighten [their] understanding” (Alma 32:28). Examples of these types of questions are:

- How have you come to know this principle is true?

- What helps you to live this principle?

- What counsel would you give to someone who is struggling to accept or live this principle?

When using questions addressed to those who are struggling, teachers need to be sensitive to those students who do not feel like they have received a witness of truth. Students might feel that the reason they have not received a witness is that something is wrong with them, or that Heavenly Father might not love them as much as others, and so on. It is good to remind students that we all receive the Spirit in different ways[10] and that we can and do receive revelation but do not always recognize it as such.[11] We can also provide the encouragement to continue qualifying for the Spirit through obedience (see John 7:17), the testimony that the Lord loves us and will help us, and the counsel to not give up asking for his guidance and for help to recognize it when it comes.

In constructing questions, it is wise for the teacher to ponder and prepare questions before the class begins. Meaningful questions are often best formulated during a contemplative time of preparation, and the best questions are received by revelation. That is not to say that the Lord will not give us these questions in our mind, “in the very hour, yea, in the very moment” of our need (D&C 100:6). He has and he will, especially after we have done all we can do (see 2 Nephi 25:23) and have followed his command to “treasure up in your minds continually the words of life” (D&C 84:85). In short, as we consistently pay the price in preparation, the Lord will reveal to us those questions that will benefit and bless our students the most.

Icebergs: Follow-up Questions

Sometimes a student shares a thought, but the teacher senses there is more the student could share. The portion of information the student initially shares might be compared to the tip of an iceberg: there is much more beneath the surface. A simple follow-up question will provide an opportunity for the student to descend from “surface-level” answers to the deeper, more meaningful thoughts and feelings. When this appropriately happens, students will disclose magnificent and monumental portions of the iceberg that can lift and edify students in the classroom.

One teacher shared an experience he had in class after he had heard the iceberg analogy. He was discussing with his students times when they had seen a source of true power. One young man, who rarely commented in class, raised his hand and said, “I have learned that priesthood power is power from God.” The teacher said he actually visualized an iceberg and then said, “Danny, it sounds like you know what you are talking about. Would you tell us more?” Danny continued, “When my little sister was born, she was born with many health complications. The doctors said she wouldn’t live for even one hour.” Then he added, “Then she died, and my dad blessed her, and she started to live again.” Concluding, he said, “She is nine years old now.”

After Danny had shared this experience, the teacher stated that a powerful feeling had entered the room. He looked at his students and asked, “Does anyone else know that priesthood power is the true power of God?” Amber raised her hand and said, “I have never had an experience like that, but when Danny was talking, I know I felt the Spirit.” The teacher later commented that, just as Danny looked back to the time his father blessed his sister as a day his testimony of the priesthood was strengthened, Amber would most likely look back to that day in seminary as a day her testimony of the priesthood was also strengthened.

Imagine if the teacher had not asked Danny the follow-up question. A meaningful, faith-fortifying opportunity definitely would have been lost. Contrast the previous experience with another occurrence a friend of mine observed in a seminary classroom a few years ago. During class a young woman raised her hand and made the comment, “I have just learned for myself that Gordon B. Hinckley is a true prophet of God!” The teacher looked at her and said, “That’s great—now back to my story.” An opportunity was lost (hopefully, the teacher asked her the next class period to elaborate). A simple follow-up prompt, such as “Please tell us more,” would have given her an opportunity to disclose the rest of the iceberg—in this case, a life-changing event. She had just learned for herself that we have a prophet of God on the earth!

I am certain that in classes I have taught I have missed many opportunities similar to this one. It is imperative, however, that teachers recognize such golden opportunities when they come and ask the appropriate questions that will lead to responses that inspire, uplift, and encourage those who are listening.

The following are examples of follow-up statements and questions that can be effective in encouraging students to appropriately share additional meaningful thoughts and feelings:

- Please tell us more.

- Teach us.

- Please explain.

- Please give us an example.

- What do you mean by that?

Another type of follow-up question helps students move from sharing experiences and thoughts to testifying about truth. After a student shares a poignant, faith-promoting experience a teacher can ask: “How has this experience strengthened your testimony of Jesus Christ?” or, “How has knowing this strengthened your faith or testimony?” Another question that can lead to fruitful answers is, “What have you learned about Heavenly Father (or Jesus Christ) from this experience?” Such questions frequently lead to responses that are filled with pure testimony. At these times, the outcomes listed in Doctrine and Covenants 50:22, of understanding, edification, and rejoicing are often realized. These questions include:

- How has this experience strengthened your testimony of Jesus Christ?

- How has this experience strengthened your faith?

- What have you learned about Heavenly Father from this experience?

- What have you learned about Jesus Christ from this experience?

- How has studying this increased your testimony of the Atonement?

- How does that make you feel about your Heavenly Father? Jesus Christ?

Anytime we speak with reverence and gratitude about our Heavenly Father, His Son Jesus Christ, or the Atonement, the outcome is power. In teaching of the importance of testifying of the Savior, President Eyring observed, “One of the offices of the Holy Ghost is to testify of the Savior and his work. There are many true things you can choose to say to your child or to your student. The Spirit testifies of all truth. And yet the surest way I know to have the Spirit come to verify what you say is to testify of the Savior. So, when the person you love and serve feels the Spirit as you testify of the Savior, it strengthens their faith. They then are more likely to choose to testify of their growing faith in him and His works. And when they do, the Spirit will confirm what they say to those who hear them. And it will reinforce their own faith.”[12]

As students respond to the invitation to bear testimony it can have a strengthening effect on them. President Boyd K. Packer said, “Oh, if I could teach you this one principle. A testimony is to be found in the bearing of it!”[13] In adding to this principle, President Packer said on another occasion, “There are two dimensions to testimony. The one, a testimony we bear to them, has power to lift and bless them. The other, infinitely more important, the testimony they bear themselves, has the power to redeem and exalt them. You might say they can get a testimony from what we say. The testimony comes when they themselves bear a witness of the truth and the Holy Ghost confirms it to them.”[14]

Point Guards: Effective Discussions

Teaching the Gospel states, “Good questions are at the very heart of good discussions.”[15] This handbook also clarifies that, “A good discussion can help students learn the value of personal inquiry in their own lives. They need to learn how to ask for help from the Lord and then to search for answers.” Furthermore the handbook reads, “A stimulating discussion is also a way to create learner readiness and help students apply what they learn.”[16] Hence, directing effective discussions allows the students and teacher to learn from each other in a setting where the Holy Ghost is active so that “all will be edified of all” (D&C 88:122). Elder Joseph B. Wirthlin stated the following pertaining to the effectiveness of discussions: “The more class members . . . discuss what the gospel actually means in their lives, the more will be their inspiration, growth, and joy as they try to solve their personal concerns and challenges.”[17]

One way to direct an effective discussion is through redirecting questions to other students in the class. For example, when a student shares a poignant insight, a teacher can then turn to another member of the class and say, “John, what can you add to what we just heard?” or “Sarah, would you tell us what you feel?” The implementation of this teaching practice is like a point guard distributing the ball to members of his team. When the teacher asks a question, it is like he passes the ball to a student who in turn answers the question and then passes the ball back to the teacher. The teacher then looks at another student and distributes the ball to him or her, and this exchange can be repeated for the duration of the discussion. As teachers redirect questions to other students, the effect it has on the team or members of the classroom is significant. There is something good that happens inside the classroom. Participation is broadened and the discussion is deepened. There is also an increased feeling of unity and strength as students get to know each other better and as they listen to and learn from one another.

One day, as I was teaching a class at the Orem Institute, my friend (whom I consider a master teacher) was observing me. He silently sat in the back of my classroom and watched my lesson as I taught a scripture block from the Book of Mormon. Following my class, I asked him for some feedback or suggestions that he thought would improve my teaching. He shared with me one thought that has really helped me as I ask and redirect questions to other students. He said, “I know you have students who won’t always raise their hands to respond but who will have things to share if you will ask them.” He added, “Watch their eyes; you will see it; you will just know it.”

I have since learned how to watch my students’ eyes, and have discovered that what my friend taught me is true—you can see it in their eyes when students have something insightful or inspiring to add. Sometimes the students give it away through nodding their heads affirmatively to what is being shared. As teachers, we can see and know by discernment when the Holy Ghost has shared something with the student that may be appropriate to share with the class. Since that time, as I have watched my students’ eyes and called on them in my institute and BYU religion classes, I will receive an occasional “I don’t know,” but the vast majority of the time the student will share helpful and inspiring thoughts and feelings, which adds power to the class.[18]

The following are examples of questions that redirect or bridge to other students:

- Who would be willing to add to what was just shared?

- How is what was shared the same or different with you?

- Is there anyone else who would like to share?

- John, what do you think about what we just heard?

- John, what would you add to what Amanda just said?

- Sarah, what do you know to be true about this principle or doctrine?

- John, will you also share your feelings about the principle we have just discussed?

- Sarah, would you tell us what you feel?

When redirecting questions to individuals, a teacher must use caution not to bridge to a student who might bring contention into the discussion or make derogatory comments regarding their classmates’ thoughts and feelings. It is one thing for a student to add another witness to the principle being discussed or add their insight or experience into the discussion, but it is quite another to bring a contrary and unedifying spirit into the classroom. A point guard is always careful where and to whom he passes the ball. He never wants to pass the ball to an opponent.

An effective way to provide opportunities for students to meaningfully participate is by redirecting questions that are asked by a student right back to the entire class. For example, a few weeks ago I was observing a class when a junior high seminary student raised her hand and asked, “Did Jesus really suffer for all of us?” It was a great question. Certainly it would have been appropriate for the teacher to bear testimony of the Atonement of Christ, but had the teacher redirected this question back to the class, it definitely could have yielded marvelous, affirming, and living testimonies borne by the students regarding Christ’s suffering for everyone, or, even better, every one. Through the use of follow-up questions and redirecting questions, the experience could have produced tremendous spiritual fruit—in this case, testimonies about the Atonement.

In addressing this topic, President Packer wrote, “How easy it is for a teacher to respond quickly to simple questions, to close a conversation that might have ignited a sparkling and lively class discussion. The wise teacher deftly and pleasantly responds, ‘That’s an interesting question. What does the class think of this?’ Or, ‘Can anyone in the class help with this interesting problem?’ A simple two-way conversation, and you’ve involved the whole class and their minds come alive and are open to teaching.”[19]

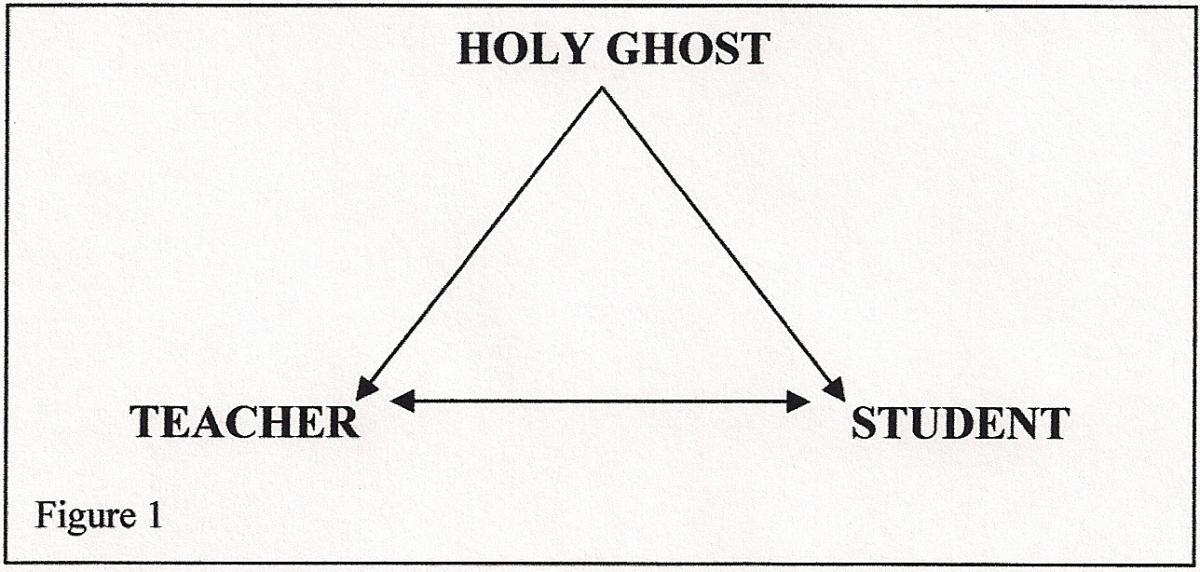

A one-dimensional chart shows the interaction between the Holy Ghost and the teacher and the student (see figure 1). The most significant questions the teacher can ask are those questions that are prompted (asked) by the Lord through the teacher, and the most meaningful responses from the students are those that are “received” or revealed to the student by the Holy Ghost. Through discernment, we might sense when such interactions have occurred between the Holy Ghost and students.

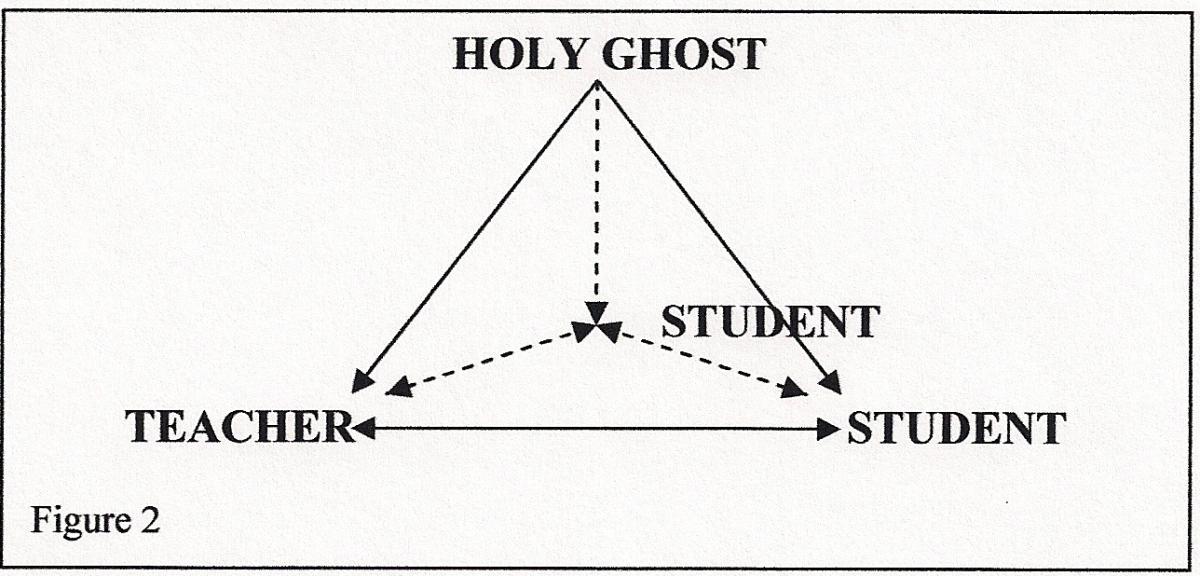

However, by adding another dimension to our chart (see figure 2), we can see that the Holy Ghost interacts not only between the teacher and student, but also between individual students as well. Such interactions between students can be spirit-filled and result in testimonies being strengthened, lives touched, and understandings increased. Likewise, when students meaningfully share their thoughts and feelings about truth, the outcome is often edification. In speaking about edification, Elder Scott said, “To me, the word edified means that the Lord will personalize our understanding of truth to meet our individual needs and as we strive for that guidance.”[20] That personalized understanding comes as we study truth, and as we hear our teacher and classmates speak truth that has been revealed to them. The Lord describes this exchange between the Spirit, teacher, and students in Doctrine and Covenants 88:122: “Appoint among yourselves a teacher, and let not all be a spokesmen at once; but let one speak at a time and let all listen unto his sayings, that when all have spoken that all may be edified of all, and that every man may have an equal privilege.”

On one occasion I observed a lesson where the Spirit was strongly active between the teacher and members of the class. It occurred while the teacher was helping his students apply the New Testament scripture mastery scriptures to their personal challenges. The teacher asked his students to anonymously write down a trial or struggle they were currently experiencing. As the students wrote their responses, the teacher circulated around the class, collected papers, and shuffled them to preserve their anonymity.

After the teacher had collected all of the papers, he took one and read it to the class. It read, "I have a friend who is struggling with addiction." The teacher said to the class, "Let's help this person by sharing with them the scripture mastery scriptures that you think would help their friend." After a short pause, a student raised her hand and said, "i think Matthew 5:14-16 might help." She continued, "I think knowing that we are the light of the world helps. We are examples to others and addictions take away from the light we hold and when we don't have the light we can't share it with others." Continuing, she said, "Also, light makes us feel good, and when we lose it its's no fun." Her concluding comment was, "We need light." The teacher thanked her and then asked, "Who else would like to help?" Another young woman raised her hand and said, "i think the answer is in Luke 24:36-39." The teacher simply said, "Okay, how?" The young woman answered, "I know these verses are about the Resurrection, but when i think of them I also think of the Atonement."[21] She then testified, "I think the thing that helps us overcome addictions the most is the Atonement of Christ." Finally she sincerely added, "The Lord gives us the strength to resist temptations, and he gives us the strength to break addictions." She said, "The key is Christ; we just need to let him help us."

By then a few more hands were lifted in the air, and students continued to share scriptures that would help a class member to in turn help a friend. Then the teacher read the next trial. The cycle was repeated one more time, with students sharing scriptures and providing insightful comments. The teacher was definitely directing an effective discussion. In fact, it was like he was conducting an orchestra with students beautifully sharing their part with richness and quality that made the class a living work of art.

Waves: An Unrushed Atmosphere

Another idea for directing effective discussions is to withstand the temptation to prematurely end a discussion when you and your students are experiencing a marvelous faith-promoting conversation. Oftentimes we feel the weight of the unfulfilled teaching outline, and we move the class away from a spiritually nourishing experience that is fortifying faith, renewing hope and having a profound effect on our students. When we feel those times when the Spirit is rich and deeply edifying, it is wise to continue the discussion, even if we do not get to the end of our outline. I have heard this referred to as "riding the wave." Once you are on a great wave, continue to ride it while it lasts. If it lasts too long, you will feel it and know it is time to move on, but many times we can abandon the wave too early. By riding the wave, we allow the Holy Ghost time to testify of pure truth that is impressed into the minds and hears of the listeners.

Recently I watched a class ride a wonderful wave. The class was speaking about times when they had “wrestled” with God in “mighty prayer” (Enos 1:2, 4). As the students shared their experiences, the Spirit washed over the entire class. One young man told of an experience where he had recently learned the Lord wanted him to focus on preparing for his mission rather than on obtaining an athletic scholarship. He had prayed to the Lord for direction in his life, and he gradually received perspective and peace. This young man concluded his experience by simply sharing pure truth. He said, “We must keep the Lord as our most important priority in our life.” The teacher paused and then asked him to state the truth again. It was one of those spiritual moments, where pure truth was spoken, and the entire class became still. Finally the teacher broke the silence and bore his own testimony. His testimony was like an exclamation point to the lesson. The class had ridden a wonderful wave that was exhilarating and stimulating for the entire class.

In speaking about his topic, Elder Scott said, "Remember, your highest priority is not to get through all the material if that means that it cannot be properly absorbed. Do what you are able to do with understanding. Determine according tot he individual capabilities and needs of your students, what is of highest priority. If a key principle is understood, internalized and made part of the students' guidebooks for life, then the most important objective has been accomplished. The best measure of the effectiveness of what occurs in the classroom is to observe that the truths are being understood and applied in a student's life." [22]

Once you are on a great wave, continue to ride it while it lasts. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Michael Moriatis.

Once you are on a great wave, continue to ride it while it lasts. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Michael Moriatis.

In a Worldwide Leadership Training Meeting, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland spoke on the importance of teaching in an unrushed atmosphere:

In discussing preparation, may I also encourage you to avoid a temptation that faces almost every teacher in the Church; at least it has certainly been my experience. That is the temptation to cover too much material, the temptation to stuff more into the hour—or more into the students—than they can possibly hold! Remember two things in this regard: first of all, we are teaching people, not subject matter per se; and second, every lesson outline that I have ever seen will inevitably have more in it than we can possibly cover in the allotted time.

So stop worrying about that. It’s better to take just a few good ideas and get good discussion—and good learning—than to be frenzied, trying to teach every word in the manual. . . .

An unrushed atmosphere is absolutely essential if you are to have the Spirit of the Lord present in your class. Please don’t ever forget that. Too many of us rush. We rush right past the Spirit of the Lord trying to beat the clock in some absolutely unnecessary footrace.[23]

I have heard an area director share the following counsel with teaches who struggle with rushing too fast and trying to cover too much material. He simply advised, "Slow down; teach less; ask a question." By so doing, he felt students would actually gain more from the experience. He explained that when we slow down, cover less, and engage students by asking a question, they will learn more, feel more, absorb more, and walk away with more than if we try to "hydrate them with a fire hose."

Sometimes it is helpful to remind ourselves that we will not be the last teacher ever to teach the students. They will learn additional principles throughout their life in personal study as well as in future church settings. Since we cannot teach them everything, we must choose to teach them principles that are most meaningful and applicable to their lives right now in a way that will have lasting impact.[24]

Teaching the Gospel suggests that we (a) carefully prepare and plan the discussion, (b) conduct the discussion under the influence of the Holy Ghost, (c) plan a discussion so that students are seeking, asking, and knocking, (d) call on students by name, (e) give students time to think, and (f) listen to students’ answers and acknowledge the response in a positive manner.[25]

Another suggestion is that teachers should not be overly concerned if a student’s comment seems to be taking the discussion in a direction that was not intended. Because we are teaching students and not lesson outlines, through the promptings of the Spirit the discussion will be guided at times away from our plan into a direction that is most fertile for our students. Just as the Liahona guided Lehi and his family into the “most fertile parts of the wilderness,” so too can our discussions be directed to those “fertile parts” that will bless and benefit our students the most (see 1 Nephi 16:14, 16). However, if the teacher feels the discussion is not fruitful, he or she can direct the discussion back on course so that it is more productive.

Cautions

Chad Webb offered the following caution and challenge that applies to asking questions and directing discussions. He stated, “Programs and teaching practices are important, but only to the extent that they accomplish the desired outcome, and that outcome is the conversion of students. Therefore, the challenge and the opportunity that is ours is to identify and implement ways of inviting the Holy Ghost into the learning experience more often and with more power.”[26] In other words, asking good questions and directing effective discussions are simply the means to a greater end, which is to help our students become converted. Elder Scott counseled, “Will you pray for guidance in how to have truth sink deep into the minds and hearts of your students so as to be used throughout life? As you prayerfully seek ways to do that, I know that the Lord will guide you.”[27]

Next, it is important to remember that, with any teaching practice, there is always a danger to overuse it. Students who are met with follow-up questions or redirecting questions after every single comment could become weary if this practice becomes monotonous or tedious. It is far more effective to use any teaching practice wisely and providentially.

Another caution: some questions are too personal to discuss in class. Teachers should not ask questions that probe into the private areas of life. For example, it is unwise to ask specific questions about past sins and worthiness. Qualifying certain questions with statements like “Without disclosing any sins, how do you feel about . . . ?” Or, “If it is not too personal, what do you think regarding . . . ?” There are times when it is wise to remind students of important boundaries of propriety. More personal questions can be asked rhetorically, and are best answered only in the minds of our students.

Finally, in regards to stimulating good discussions, teachers of the gospel have been cautioned not to use adversarial debate, controversy, speculation, or sensationalism as the catalyst of a good discussion. In speaking of avoiding adversarial discussions, Elder Dallin H. Oaks gave the following counsel: “The Lord’s prescribed methods of acquiring sacred knowledge are very different from the methods used by those who acquire learning exclusively by study. For example, a frequent technique of scholarship is debate of adversarial discussion, a method with which I have had considerable personal experience. But the Lord has instructed us in ancient and modern scriptures that we should not contend over the points of doctrine (see 3 Nephi 11:28–30; D&C 10:63). . . . Techniques devised for adversary debate or to search out differences and work out compromises are not effective in acquiring gospel knowledge.”[28] Teaching the Gospel cautions teachers and counsels that they should avoid asking a “controversial question just to stimulate a lively discussion. This may frustrate the students and create contention in the class, which grieves the Spirit.”[29]

Softballs: A Quieter Class

One of the greatest challenges (if not the greatest) that teachers face in asking questions is when a class will not respond to them or will not engage in an effective discussion. In classes that are predominantly comprised of passive, nonparticipative, or shy students, the teacher finds himself or herself carrying the bulk of the load from the beginning to the end of class. These classes seem long and are often boring and tedious for the teacher and the students.

This past summer we spent time in an in-service training meeting discussing ideas that would help us work with reticent students and classes. During this meeting we brainstormed what we can do as teachers to help students open up and verbally participate more.

One of the items we discussed is making sure we give our students adequate time to formulate their answers. In speaking on this point, Elder Neal A. Maxwell said, “Provide moments of deliberate pause. The Spirit will supply its own ‘evidence of things not seen.’ And don’t be afraid of inspired silences.”[30] Often the best responses come after a period of “inspired silence.” One experienced teacher wrote,

Like most people, I am conditioned to interpret silence as a symptom of something gone wrong. . . . Panic catapults me to the conclusion that the point just made or the question just raised has left the students either dumfounded or bored, and I am duty-bound to apply conversational CPR. . . . But suppose my panic has misled me and my quick conclusion is mistaken. Suppose that my students are neither dumbfounded nor dismissive but digging deep; suppose that they are not ignorant or cynical but wise enough to know that this moment calls for thought; suppose that they are not wasting time but doing a more reflective form of learning. I miss all such possibilities when I assume that their silence signifies a problem.[31]

“Be patient!” is the counsel given to teachers in Teaching the Gospel regarding these times of silence when no one responds to the question. Continuing, the handbook reads, “Students often need time to find the answer in the scriptures or to think about the question and what they want to say. The silence should not trouble the teacher if it does not go on too long. On the other hand, sometimes there is no response because the question is not clear. If this is the case, the teacher may need to rephrase the question or ask the students if they understand what was asked.”[32]

We also spoke about the advantage of speaking directly with our students about the importance and spiritual benefit of responding to questions. Teaching the Gospel says, “From time to time, teachers can remind students of what they can do to encourage the Spirit of the Lord to be with them. . . . The discussion could also focus on behaviors that . . . are pleasing to the Spirit,”[33] including “opening our mouths” (D&C 28:16). Elder David A. Bednar stated, “Are the students we serve acting and seeking to learn by faith, or are they waiting to be taught and acted upon? Are you and I encouraging and helping those whom we serve to seek learning by faith? You and I and our students are to be anxiously engaged in asking, seeking, and knocking (see 3 Nephi 14:7).” Elder Bednar added, “Learning by faith requires spiritual, mental, and physical exertion and not just passive reception. It is in the sincerity and consistency of our faith-inspired action that we indicate to our Heavenly Father and His Son, Jesus Christ, our willingness to learn and receive instruction from the Holy Ghost.”[34] In this same regard, Elder Scott succinctly stated, “When you encourage students to . . . respond to a question, they signify to the Holy Ghost their willingness to learn.”[35]

If students understand the importance of responding to questions, not just as “recording devices that play back information for a class discussion . . . with little thought of future use,”[36] then the miracle of edification and the deepening of conversion can take place. One administrator commented that the most meaningful spiritual experiences he has observed in the classroom are when students share their thoughts, feelings, and experiences with the class. Elder Scott summarized this principle by stating, “Assure that there is abundant participation because that use of agency by a student authorizes the Holy Ghost to instruct. It also helps the students retain your message. As students verbalize truths, they are confirmed in their souls and strengthen their personal testimonies.”[37] Elder Carlos E. Asay succinctly stated, “A pure doctrine taught by a pure [young] man or [young] woman with pure motive will result in a pure testimony.”[38]

In our summer in-service we also discussed the importance of creating a safe atmosphere where students feel free to share what is on their mind and in their heart. Criticism, put downs, and other tactics that make students feel dumb after they make comments are not tolerated in such a class. Additionally, teachers can emphasize that there is no such thing as a “dumb question” or a “dumb comment,” and those times when students miss the target in their response, a wise teacher can carefully rescue them by saying, “You know what, I asked the question wrong. Let me reword it and ask it again.”

Along with this point, teachers can also foster a spirit of inquiry in class. As students feel comfortable in asking, seeking, and knocking, they can receive answers to their questions. It is wonderful to observe classes where students freely raise their hands to ask questions that they are pondering and to watch the teacher and the other students assist by sharing with the inquisitive student what they know. It is good to see several hands up in the air, each with either a question or a thought about the principle that is being discussed. In these types of settings students feel secure to earnestly ask, seek, and knock, and as a result their questions are answered. When the spirit of inquiry exists in a class, students spontaneously ask those questions that are relevant to their own understanding, lending to an active classroom experience.

Another way we discussed that can help students verbally participate more is by asking some students easier questions at first to break the ice. As students respond to simpler questions first, it will often prime the pump so that they will feel the desire to continue in the discussion. This idea of first asking a simpler question is like lobbing a softball to students. As we “lob softballs,” it can help some students build confidence as well as increase their desire to continue participating.

Many of us have either taught or witnessed an inexperienced batter learn to hit a ball (typically using a plastic ball and an oversized plastic bat). Usually, the pitcher draws near to the hitter, and then asks him or her to “check swing” the bat. Then the pitcher tries with precision to pitch the ball in the exact location where the bat was just swung. Once the inexperienced batter (usually a small child) hits the ball, the pitcher (usually a parent) is verbally supportive, validating, and congratulatory. Likewise, when a teacher lobs a softball—an easier question—at a student, the teacher is providing the student with a simple, easy-to-answer question. Once the student makes contact and answers the question appropriately, the teacher can then positively reinforce the student. This positive, genuine reinforcement has an encouraging effect on students. It can help students to try again and participate more. Teaching the Gospel states, “Those students who know they are loved, respected, and trusted by their teacher are most likely to come to class ready to learn.”[39] Furthermore, as our students know their thoughts and feelings are valued, they will often feel more comfortable and participate in sharing their testimonies, experiences, questions, and ideas.

Lobbing a softball can also include asking students to respond to the question first on paper. This allows students time to process the question and better formulate their thoughts. This time can also be used for students to ponder and seek for inspired responses. After they have written their thoughts, the teacher calls on them to either read their written comments or to summarize them verbally. Students can do this first in smaller groups, which can be less intimidating, followed by speaking to the class at large. In sum, lobbing softballs can help certain students become more engaged in classroom discussions.

It is important to remember that although some students or classes need softballs to help them begin to engage in discussions, other students need other, more skillful pitches to help pull them into the game. Some students might find playing softball with a plastic ball and oversized bat not as fulfilling. The principle is to pitch to the needs and abilities of our students.

In our summer in-service meeting, we discussed several other ideas to help reluctant students to share more. The discussion included (a) increasing class unity so students are comfortable in sharing with each other, (b) preparing lessons that are scripture-based and spiritually nourishing so students feel the power and inspiration to share, (c) consistently preparing lessons that are interesting, relevant, and enjoyable, so that healthy learner readiness is maintained[40] (when learner readiness is low, students often do not feel the desire to respond to even good questions), (e) formulating questions for students that require more than the superficial answers of “pray,” “go to church,” and “read the scriptures” and most importantly, (f) receiving inspired questions from the Lord.

Chad Webb addressed this topic and said, “Please don’t get discouraged if your students don’t respond immediately to the opportunity to participate more. There are wonderful blessings that will come as we patiently help them to become good learners. It doesn’t always happen with our first attempt. It will take some time and some effort.”[41]

Finally, Elder Scott stated, “Don’t let Satan lead you to underestimate your worth. As a mission president, it was easy to distinguish the difference between a young man or woman who had consistently attended seminary or institute from those who had missed those enriching experiences. You may be discouraged when parents who are able to help their children don’t do it. You may be less than enthusiastic when a student comes to class and doesn’t appear to be concentrating. Accept the challenge to get him or her actively engaged. Don’t let Satan lead you to underestimate your worth and the impact for good you have in the lives of students. It can be immense.”[42]

Conclusion

When Jesus appeared to the Nephites, he taught the people for three days. The record informs us that “he did teach and minister unto the children of the multitude of whom hath been spoken, and he did loose their tongues, and they did speak unto their fathers great and marvelous things, even greater than he had revealed unto the people; and he loosed their tongues that they could utter” (3 Nephi 26:14).

Like Jesus to the Nephites, a modern prophet of God shared his observation about the youth of our day. President Eyring said, “In recent months I have heard deacons, teachers, and priests give talks which are clearly as inspired and powerful as you will hear in this general conference. As I have felt the power being given to young holders of the priesthood, I have thought that the rising generation is rising around us, as if on an incoming tide. My prayer is that those of us in the generations which have come before will rise on the tide with them.”[43]

In this paper, I have shared analogies (icebergs, point guards, waves, and softballs) that can help teachers to improve their use of questions and discussions in order to increase understanding and edification. Such questions and discussions provide opportunities for our students to express thoughts and feelings that are inspired by the Spirit. And just as he did in ancient days, the Lord can also loose the tongues of our students so they too can share great and marvelous things. Similarly, as President Eyring said, we too can hear our students respond in ways that are inspired and powerful.

In sum, Teaching the Gospel succinctly states, “Effective teaching is edifying teaching, and people are more likely to be edified when they participate in learning under the influence of the Spirit. . . . Asking good questions and directing effective discussions are primary ways to encourage that participation.”[44]

Notes

[1] Teaching the Gospel: A Handbook for CES Teachers and Leaders (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1994), 37.

[2] Teaching the Gospel, 37–38.

[3] Richard G. Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth,” address to CES religious educators, February 4, 2005, 3.

[4] Henry B. Eyring, “The Lord Will Multiply the Harvest,” An Evening with Elder Henry B. Eyring, February 6, 1998, 6.

[5] Chad H. Webb, “Deepening Conversion,” CES satellite broadcast, August 7, 2007, 4; emphasis added.

[6] In his book Teach Ye Diligently, President Packer teaches, “If we learn in order to serve, to give to others, and to ‘feed’ others, we will find the acquisition of subject matter much easier. . . . Then there will come to us the full meaning of this scripture; ‘He that findeth his life shall lose it: and he that loseth his life for my sake shall find it’” ([Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1975], 191).

[7] Teaching the Gospel, 15.

[8] Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth,” 6.

[9] Seminaries and Institutes of Religion, The Teaching and Learning Emphasis: Training Document.

[10] Elder S. Dilworth Young taught, “I can testify to you that there will be none of you [who will] have any adventure greater, more thrilling, and more joyful than finding out how to interpret the Spirit which comes into you bearing testimony of the truth. Young folks have to learn how, so do we older folks. We have to find out the technique by which the Spirit whispers in our hearts. We have to learn to hear it and to understand it and to know when we have it, and that sometimes takes a long time” (in Conference Report, April 1959, 59). Similarly, President Thomas S. Monson stated, “As we pursue the journeys of life, let us learn the language of the Spirit” (“The Spirit Giveth Life,” Ensign, June 1997, 5).

[11] An example of this principle is found in Doctrine and Covenants 6:14–15. The Lord taught Joseph Smith Jr. and Oliver Cowdery that “as often as thou hast inquired thou hast received instruction of my Spirit. If it had not been so, thou wouldst not have come to the place where thou art at this time.” The Lord continues in the next verse, “Behold, thou knowest that thou hast inquired of me and I did enlighten thy mind; and now I tell thee these things that thou mayest know that thou hast been enlightened by the Spirit of truth.”

[12] Henry B. Eyring, “Raising Expectations,” CES satellite training broadcast, August 4, 2004, 3–4.

[13] Boyd K. Packer, “The Candle of the Lord,” Ensign, January 1983, 54; emphasis in original.

[14] Boyd K. Packer, Let Not Your Heart Be Troubled (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1991), 15; emphasis in original.

[15] Teaching the Gospel, 38.

[16] Teaching the Gospel, 37.

[17] “Teaching by the Spirit: A Conversation with Elder Joseph B. Wirthlin and Elder Gene R. Cook,” Ensign, January 1989, 5.

[18] President Howard W. Hunter stated, “Do not fall into the trap that some of us fall into by calling on the ones who are always so bright and eager and ready with the right answer. Look and probe for those who are hanging back, who are shy and retiring and perhaps troubled in spirit” (Eternal Investments, An Evening with President Howard W. Hunter, February 10, 1989, 4). In working with an overzealous student, see Packer, Teach Ye Diligently, 172–73.

[19] Packer, Teach Ye Diligently, 68.

[20] Richard G. Scott, “Helping Others to be Spiritually Led,” address to religious educators at a symposium on the Doctrine and Covenants and Church history, Brigham Young University, August 11, 1998, 11.

[21] A common misconception is that the Resurrection is not part of the Atonement. Preach My Gospel states, “The Atonement included His suffering in the Garden of Gethsemane and His suffering and death on the cross, and it ended with His Resurrection” (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004), 52.

[22] Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth,” 2–3.

[23] Jeffrey R. Holland, worldwide leadership training meeting, February 10, 2007, in “Teaching and Learning in the Church,” Ensign, June 2007, 91.

[24] “Teachers should be careful not to end a good discussion prematurely in an attempt to cover all the material they have prepared. What matters most is not the amount of material covered but that class members feel the influence of the Spirit, increase their understanding of the gospel, learn to apply gospel principles in their lives, and strengthen their commitment to live the gospel” (“Gospel Teaching and Leadership,” Church Handbook of Instructions, Book 2, 304).

[25] Teaching the Gospel, 38.

[26] Webb, “Deepening Conversion,” 1.

[27] Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth,” 2.

[28] Dallin H. Oaks, “Alternate Voices,” Ensign, May 1989, 29.

[29] Teaching the Gospel, 38.

[30] Neal A. Maxwell, “Teaching by the Spirit—The Language of Inspiration,” in Old Testament Symposium Speeches, 191, 1–6, also found in Church Educational System, Teaching Seminary: Preservice Readings (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004), 38.

[31] Parker J. Palmer, The Courage to Teach (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1998), 82.

[32] Teaching the Gospel, 38.

[33] Teaching the Gospel, 25.

[34] David A. Bednar, “Seek Learning by Faith,” address to CES religious educators, February 3, 2006, 3; emphasis added.

[35] Scott, “Helping Others to be Spiritually Led,” 3.

[36] Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth,” 3.

[37] Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth,” 3. There are other ways students can demonstrate to the Lord they are willing to be taught by the Spirit. The Church News reported, “By way of tradition, BYU—Idaho students hold their scriptures in the air at the weekly devotional assemblies to show they are ready to be taught the word of God. Elder Bednar explained the reason behind the outward symbol of inward preparation that he began seven years ago upon his arrival as the fourteenth president of the university. Elder Bednar stated, “I choked with emotion as I watched you hold up your scriptures today. You may wonder, ‘Why does Elder Bednar always have us raise our scriptures?’ The answer is simple. Our study and use of the scriptures is an invitation to receive revelation and be tutored by the Holy Ghost” (“New Apostle Addresses BYU—Idaho Students,” Church News, November 20, 2004, 3).

[38] Carlos E. Asay, quoted in Steven T. Linford, “Instruct, But More Importantly Inspire,” Religious Educator, 6, no. 3 (2005): 49.

[39] Teaching the Gospel, 13–14.

[40] Teaching the Gospel, 14.

[41] Webb, Deepening Conversion, 3.

[42] Scott, “To Understand and Live Truth,” 6; emphasis added.

[43] Henry B. Eyring, “Be Ready,” Ensign, November 2009, 60; emphasis added.

[44] Teaching the Gospel, 37.