Half a Century of Teaching

Susan Easton Black and Richard O. Cowan

Susan Easton Black, Richard O. Cowan, "Half a Century of Teaching," Religious Educator 11, no. 3 (2010): 215–223.

Susan Easton Black (susan_black@byu.edu) and Richard O. Cowan (richard_cowan@byu.edu) were professors of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this article was written. At the time Dr. Cowan was entering his fiftieth year of teaching.

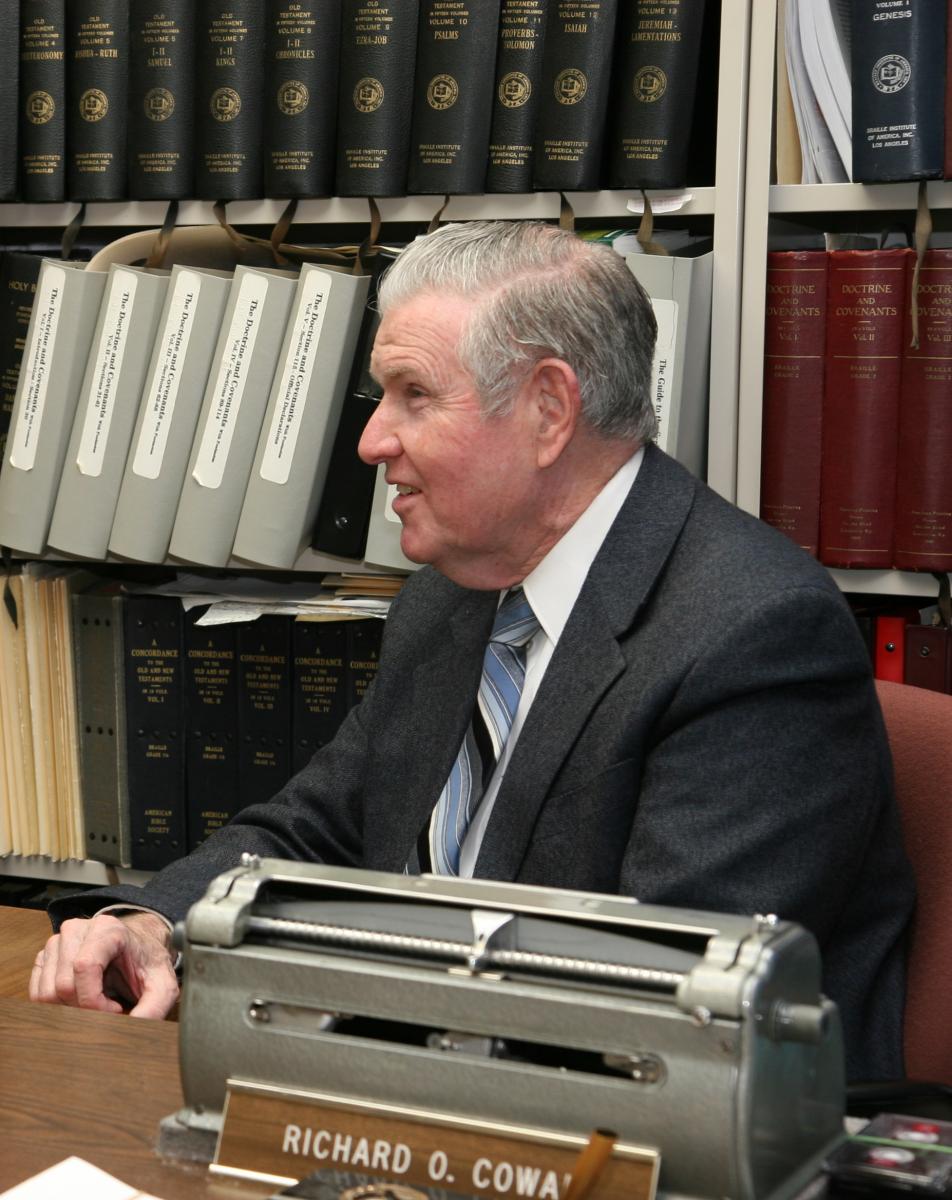

Richard O. Cowan was a professor of Church History and doctrine when this was written. He had just entered his fiftieth year of teaching at BYU. Richard B. Crookston.

Richard O. Cowan was a professor of Church History and doctrine when this was written. He had just entered his fiftieth year of teaching at BYU. Richard B. Crookston.

Black: When did you first discover that you had a visual problem?

Cowan: When I was still very small, my parents asked each other, “Why doesn’t he look at us?” and “Why does he stare at the lights?” To get answers to these and related questions, various specialists examined my eyes. I was diagnosed with atrophy of the optic nerve, with the likelihood of my eyesight becoming progressively worse. Decades later, my condition was identified as retinitis pigmentosa. This disease has steadily reduced my vision, causing it to fade from vague outlines in my youth to near complete loss of sight in recent years. But it should be noted that my blindness has been only an inconvenience, not a debilitating problem. Of course, I would like to see perfectly well and enjoy the beauties of nature and the smiles of loved ones, but I am content.

Black: Do you feel that visual impairment has brought you closer to your Father in Heaven?

Cowan: Growing up with a visual problem, I often wondered what my life’s work would be or even could be. Would I become a helpless beggar standing on street corners asking for alms? Was there an alternative? Involvement in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and my study of the scriptures gave me a more hopeful perspective and outlook toward life. Perhaps out of necessity, I came to rely more and more on the Lord for direction and support. Two favorite passages from scripture that have helped me are Moroni’s explanation that “weakness” can help us grow (see Ether 12:27) and the Lord’s promise to lead us “by the hand” if we are humble and prayerful (D&C 112:10).

Black: Do you have advice for students who experience physical limitations?

Cowan: It’s important to develop skills and tactics to work around the disability. Although independence has its place, be willing to receive help from others. Be sure you really can’t do something before you decide you can’t do it. Make certain that you keep as many doors open as possible. Don’t give up. Pray to the Lord for his guidance and help. Rather than demanding opportunities, I felt that I needed to earn them.

Black: Through the years, you have become well known for your speaking ability. Has speaking to large groups come naturally to you?

Cowan: The Church provided opportunities for me to speak publically. After I gave my first two-and-a-half-minute talk at age seven before the grown-ups in senior Sunday School, the person conducting remarked I was a “future Orson Haynie”—a respected gospel teacher in my ward. This was quite a compliment. So I got off to an early start.

Black: When did you discover you had a talent for writing?

Cowan: In the eighth grade, I won a gold medal from the American Legion for an essay, “America’s Contribution to World Peace.” In junior high, I also had the unusual experience of writing a humor column in Spanish (obviously with my teacher’s help) for our school newspaper. In my later teens, I wrote articles for the California Intermountain News, a small privately published newspaper serving Latter-day Saints in Southern California. My regular beat dealt with elders quorum news. At the time, I had not yet been ordained to that priesthood office.

Black: What do you consider to be the first spiritual turning points in your life?

Cowan: When I was fifteen years old, my mother took me to the home of Orson Haynie, our stake patriarch and the speaker to whom I had been compared years before, so I could receive my patriarchal blessing. I felt spiritual power as he placed his hands on my head. Certain passages of the blessing caught my attention. The promise I would be sealed in the temple to “one of the fair daughters of Zion for time and all eternity” was of particular interest. I wondered at the meaning of his words, “You shall raise your voice and wield your pen in declaring salvation and exaltation to our Father’s children who live upon the earth.” I was grateful for the affirmation that “the Lord loves you and is mindful of your condition in life” and the assurance that “your influence shall not be dimmed nor your usefulness curtailed because of physical handicap or disability.” The blessing gave me courage and hope as I anticipated the next chapters of my life.

The second turning point occurred in 1952 when I was a freshman in college. President David O. McKay, during a visit to Southern California, gave me a blessing in which he said, “The Lord is near you, and he will continue to be at your side and bless you with powers beyond your natural ability to accomplish much good. You will fill a fine mission, a mission of service to your fellowmen, and you will have a life of happiness and joy.” While this blessing was being pronounced, I was very conscious of the presence of a spiritual power.

Black: Did you serve the promised mission?

Cowan: I was called to a Spanish-speaking mission, which at the time covered the states of Texas and New Mexico. It was the only “foreign mission” within the boundaries of the United States. I had many great experiences and some humorous ones as well. For example, on one occasion a minister demanded scriptural citations on a given topic. I inconspicuously slipped my hand into the small binder in my lap, reading Braille notes, and gave him more references than he had anticipated. When he complimented me on my knowledge of the scriptures, I simply replied, “I have them at my fingertips.” I had earlier resented needing to learn Braille but on this occasion concluded that there had been value in doing so. The highlight of my mission was meeting my eternal companion, Dawn, who was also serving as a missionary in Texas.

Black: When did you decide to become a teacher of religion at Brigham Young University?

Cowan: As a missionary, I attended a district conference on March 7, 1954, in Las Cruces, New Mexico. I met Elder Clifford E. Young, an Assistant to the Twelve, who asked me how I felt about my missionary service. I spoke of loving everything about the work and expressed the hope of serving in the Church throughout my life. I then had the opportunity to ask Elder Young a few questions about the gospel. As he answered them, I had the distinct feeling that I wanted a career that would provide this type of contact with General Authorities. The impression I received was, “Teach religion at Brigham Young University.” As a result, this became my goal.

Black: To reach your goal meant much study at the university level. How did you handle all the work involved in furthering your education?

Cowan: With the help of readers who were fellow students in my classes, as well as my mother, I worked to complete my bachelor’s degree at Occidental College in Southern California. My hard work paid off. At the beginning of my senior year, I was elected a member of Phi Beta Kappa, the leading national scholastic fraternity. The election entitled me to wear the coveted gold key, although I have hesitated to do so for fear of appearing boastful.

Black: Did you enter graduate school immediately after completing your undergraduate degree? If so, how did you finance your further education?

Cowan: I was fortunate enough to be awarded a Danforth Fellowship, which covered tuition and all living expenses through the three years it took me to complete my master’s and PhD in American history at Stanford University. I believe one reason that I received this scholarship was because the Danforth Foundation promoted teaching of religion at the college level. They were looking for applicants with a good academic record, interests in religion, and an aptitude for teaching. I also received from Recordings for the Blind of New York City, one of four $500 scholarships given to visually impaired students. The award was presented to me by President Dwight D. Eisenhower at the White House. He greeted each of the four recipients in the famed Oval Office. I recall that he asked each of us what we planned to do following graduation. I replied, “I would like to teach Latter-day Saint Church history at Brigham Young University.” “Very fine,” the president said.

Black: Were you encouraged to pursue teaching religion as a profession by administrators in the Church Educational System?

Cowan: In December 1959, a top CES administrator frankly advised me that my future did not lie in the classroom. He did not think that a visually impaired person could relate effectively to students. I viewed his discouraging comments as a challenge that I needed to meet, so I just moved forward with my endeavors.

Black: Then who encouraged you to join the BYU faculty?

Cowan: Each year the Danforth Fellows held a weeklong conference in Michigan. It was there I met Daniel H. Ludlow, who encouraged me to apply for a position at BYU. He encouraged his colleagues at BYU to give me a chance. David H. Yarn, dean of the College of Religious Instruction, told me that there was a need for a faculty member with my specialty. My most positive assurance came, however, from Elder Harold B. Lee. As he was interviewing me for a faculty position, he explained that building faith was the only reason for Church schools and asked me if I could strengthen the testimony of students. I assured him that this was my desire. Following the interview, on January 25, 1961, one day after my twenty-seventh birthday, I received a formal letter offering me a position as an assistant professor in religion. I promptly wrote a letter of acceptance.

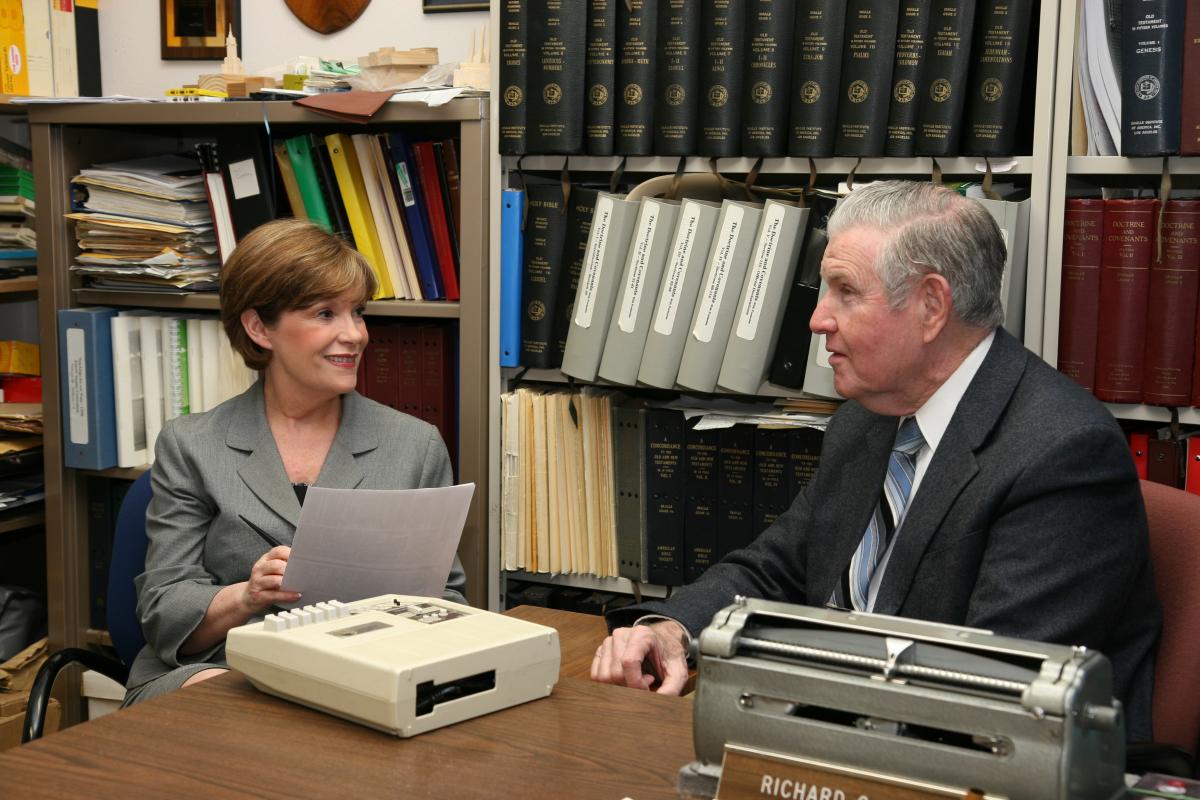

Susan Easton Black interviews Richard O. Cowan. Richard B. Crookston.

Susan Easton Black interviews Richard O. Cowan. Richard B. Crookston.

Black: What do you believe is the appropriate role of a faculty member in Religious Education at BYU?

Cowan: Any university professor needs to be a scholar, researching and publishing. In Religious Education, they should also be excellent teachers; this doesn’t mean just academic excellence, but the ability to build faith and encourage students to strengthen their own testimonies.

Black: Is it important to convey your testimony of the restored gospel to students in a classroom setting?

Cowan: I have two teaching objectives in the classroom—spiritual and academic. Spiritually, I try to reflect Elder Harold B. Lee’s emphasis to build testimony. Academically, I try to help my students master the subject. I think it is important for students to know that there is no conflict between being a respected scholar and being an active member of the Church who has faith in the gospel.

Black: Have you enjoyed your associations with other faculty members in Religious Education?

Cowan: As a junior faculty member, I looked up to scholars like Hugh Nibley and Sidney B. Sperry. Now as a senior faculty member, I enjoy the association of younger colleagues. Each one has talents that bless the lives of students.

Black: Have you seen a change in students through the years?

Cowan: I believe they are better prepared than ever before; seminary has become increasingly effective in teaching students to use the scriptures. Although there are always a few exceptions, students seem to be more motivated than ever.

Black: How have you been recognized for your outstanding teaching?

Cowan: Near the end of my fourth year at BYU, on May 13, 1965 during an assembly in the Smith Field House, I was surprised to hear that I had been voted the professor of the year. In 1979 I received the Karl G. Maeser Excellence in Teaching Award and in 1983 Continuing Education’s Outstanding Teacher Award. In 2001, I was recognized for helping make the campus a friendly place for those with disabilities, and two years later was chosen to give the annual Phi Kappa Phi lecture. In 2008 my colleagues in Religious Education gave me the Robert J. Mathews Teaching Award.

Black: What led you to focus on twentieth-century Church history?

Cowan: Dean David Yarn encouraged me to become an expert in some specific area of research. After talking about my graduate study and interests, we concluded together that I should focus on twentieth-century Church history. This decision has proved to be a blessing to me. Some may wrongly suppose that such a study would undermine my faith. Just the opposite: my faith is stronger because of it. As I discovered that Church leaders were human and had all the limitations of our mortal condition, it has caused me to marvel all the more when I consider their inspiring leadership, insightful teachings and remarkable accomplishments. This has given me a certain knowledge that the gospel is true and that our Heavenly Father and Lord Jesus Christ are directing this Church.

Black: What led to your particular interest in temples?

Cowan: It has been a lifelong interest. My love of temples goes back to my youth, when our stake in California sponsored excursions to the St. George and Mesa temples. These were choice experiences I shared with other youth who had the same ideals and interests. Then I attended the dedication of the Los Angeles Temple by President McKay. This occurred only days after returning from my mission. As a new BYU faculty member, I enjoyed meetings in the Manti Temple in which Hugh Nibley talked with the faculty about temples and temple worship. About a decade after coming to BYU, I enjoyed attending the Provo Temple dedication and have enjoyed many others since that time.

Black: As a prolific writer of Church history, what has been your main objective?

Cowan: An important objective in my writing has been to build faith. To this end, I have sought to include faith-promoting stories where relevant. Over the years, I have learned the importance of checking these accounts thoroughly to be sure that the facts are accurate. I don’t want questionable facts to become an excuse for doubting a story that was intended to bolster one’s faith.

Black: Have you had opportunities to share your writing talents in Church publications?

Cowan: I have had many opportunities to write articles for Church magazines. The privilege has expanded beyond that, however. Beginning in 1965, I was called as a writer for Church manuals. I was invited to write a history of the Lamanite program for Elder Spencer W. Kimball, a review of priesthood programs for the Correlation Committee, and a two-volume history of the Missionary Training Center. For over a decade I was chairman of the Gospel Doctrine writing committee. I believe that these Church callings were partial fulfillment of my patriarchal blessing, which promised that I would “wield [my] pen in declaring salvation and exaltation to our Father’s children.”

Black: Which of your personal writings do you view as the most significant?

Cowan: I have now written or coauthored sixteen books. In retrospect, I believe Temples to Dot the Earth may have had the broadest impact. The Latter-day Saint Century and several books on the Doctrine and Covenants have also found a large audience.

Black: You have had many opportunities to personally interact with the leaders of the Church. Is there one experience that stands out above the others you’ve had in recent years?

Cowan: While working on our book The California Saints, I arranged to be present at the dedication of the San Diego temple. President Thomas S. Monson, who was conducting the session, without any prior notice announced, “We would now like to hear from someone who sees things a little differently than most of us, Brother Richard O. Cowan.” “Oh wow!” I thought in total shock. In my remarks I explained how we leave the world behind as we enter the temple. I then noted that the unusual height of the San Diego temple’s celestial room ceiling “reminds us of ascending or being lifted up into the presence of God.”

Black: Have you held any administrative assignments at BYU?

Cowan: From 1994 to 1997, I served as chair of the Department of Church History and Doctrine. I enjoyed working with my colleagues and supporting their teaching and scholarship. Being a member of the Administrative Council gave me the feeling of being a part of and a contributor to decisions affecting Religious Education.

Black: What other experiences have been significant to you at BYU?

Cowan: In 1989 I taught at the Jerusalem Center. I found it spiritually exciting to walk where Jesus walked. Then on April 3, 2007, I had the great privilege of speaking at the campus devotional in the Marriott Center. That same month, I began teaching spring term at BYU–Hawaii. I gained a new appreciation for how BYU–Hawaii is building bridges with countries in East Asia, including mainland China.

Black: How have you changed over the years?

Cowan: I believe I am less dogmatic about things that don’t matter. At least when I look at exams written years ago, I realize that I am not as sure about certain facts or interpretations as I once was. I find it much easier now to be humble yet certain about truths I do know.

Black: You are beyond the traditional age of retirement. What has kept you at the university?

Cowan: I had assumed that I would retire when I turned sixty-five. About ten years before that time, however, I learned that the university had adopted a new policy that did away with the mandatory retirement age. I have thoroughly enjoyed the privilege of continuing my service at BYU.

Black: Are you happy with the contributions you have made to religious scholarship?

Cowan: Probably most of us feel that we haven’t accomplished all we would like and wish we could do more. Still, I am grateful for the many opportunities afforded me as a faculty member at BYU, and I hope I have made some contributions. Yet I am more excited about the opportunities that are ahead.

Black: What does the future hold?

Cowan: I look forward to finishing my first half century of teaching. I have a wonderful family that cares about me. My wife, Dawn, our six children, twenty-two grandchildren, and a new great-grandson bring me much joy. Another joy began on January 19, 2008, when I was called to be a stake patriarch. Realizing the impact my own patriarchal blessing has had on my life, it is now my great opportunity and awesome responsibility to give such blessings to others.