Return to the Sacred Grove

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Donald L. Enders, Larry C. Porter, and Robert F. Parrot

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Donald L. Enders, Robert F. Parrot, Larry C. Porter, "Return to the Sacred Grove," Religious Educator 11, no. 2 (2010): 147–157.

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel (holzapfel@byu.edu) was a professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this was written.

Donald L. Enders (endersdl@ldschurch.org) was senior curator at the Museum of Church History and Art in Salt Lake City when this was written.

Robert F. Parrot was Sacred Grove manager when this was written.

Larry C. Porter (larry_porter@byu.edu) was a professor emeritus of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this was written.

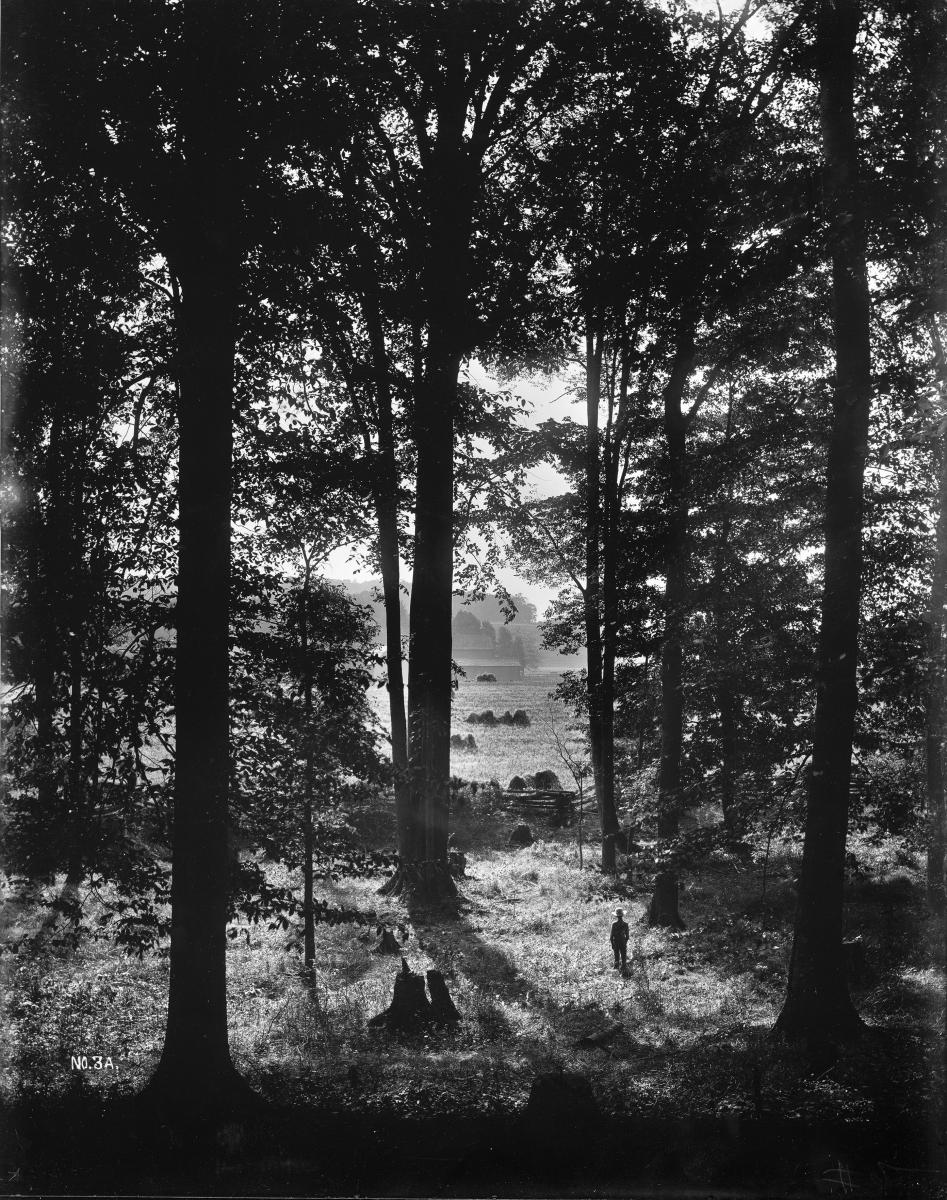

Sacred Grove, Manchester, New York, August 13, 1907, George Edward Anderson Collection, Church History Library.

Sacred Grove, Manchester, New York, August 13, 1907, George Edward Anderson Collection, Church History Library.

The Sacred Grove is part of a four-hundred-year-old forest that covered much of western New York at the time of the Smith family's arrival in the area in 1818 or 1819. Today, there are six trees that we know to be well in excess of 200 years old. There are also six to eight trees scattered throughout the grove that are between 180 and 200 years old. All of these trees are considered "witness trees" because they were likely in the grove at the time of the First Vision.

Holzapfel: Thank you for joining us today in the Sacred Grove. Don [Enders], please tell us briefly about this special place and what you have observed during your work with the Church history sites in New York.

Enders: Over the years, the Sacred Grove has gone through quite a bit of change. It was a dozen years ago that the Church hired Robert Parrot to manage this woodland. During these years we have seen that if we are patient, let Mother Nature do her work, assist her a little, and pray for the blessing of heaven upon this sacred place, it can renew itself. And it has indeed done that to a large extent. It is now healthier than it has been in the last hundred years. It is extremely fitting that the God of nature prepared this place for the time when he would appear with his Son to the boy Joseph Smith and inaugurate the work of the Restoration. The grove stands as a witness to that great event, the First Vision. So we are very pleased to see the grove root itself in more healthy terms, with plants that have long been absent now able to germinate and find place again, along with the return of wildlife, all of which are evidences that the grove is doing better.

Years ago we became aware that the grove needed some help. We arranged in 1998 for Environmental Design and Research, a respected horticultural firm at Syracuse, New York, to do an extensive study of the grove. Their assessment led to the Church hiring Robert Parrot, a specialist in forest management, to care for this sacred woodland. We are extremely pleased with the way the land has become healthy, productive, natural, and safe under his watchful eye. It has been inspiring to quietly watch the grove renew itself these last dozen years.

Holzapfel: Larry [Porter], please give us a brief history of your own experience with the Sacred Grove and what you have observed.

Porter: I first came to the grove in 1968. When I walked out to the grove, it had more the appearance of a park. The forester at that time made sure that if a tree needed to come down, it came down. If a tree had problems, such as rotting on the interior, they would clean it out, put cement into the base, and use that to preserve the trees. It was a different philosophy of management of the grove at that particular time. But I recall very vividly coming out into the grove and being by myself, very appreciative of the things that happened in this locale and not knowing the exact spot but nevertheless offering up my prayers to heaven in regard to Joseph Smith’s vision and the success of our visit in gathering the material.

Enders: I first came here in 1961. I have a recollection of those days. I was a missionary for the Church. We met at pageant time in the grove and had the opportunity to walk about the grove, actually into the grove, off the path. I remember that there was much bare ground, and to a large extent you could see across the woodlands. Of course, I was in no position to know how the grove was being taken care of. I do not think a thought about its maintenance ever entered my mind. I just supposed somebody knew what was going on. Maybe it was left only in the hands of the God of nature. So I certainly had perspective but not much thought about what needed to unfold as a maintenance program. Through the years, as I have worked with the Historical Department, I have become aware that there needed to be a maintenance focus. I remember that until a dozen years ago, when a tree needed to come out someone would come in with equipment, drive right into the woodlands with big heavy trucks, compact the soil, yank those critters out, cut those limbs off, load them up, grind them down, and be out of here. I have come to appreciate in the past dozen years the insights of a person like Charles Canfield, then director of the historic site, who had the sense to say, “We need to consider how we treat the grove.”

Porter: I think they made a grand choice. When I came here in 1968, the grove was open, as you have indicated. In the late 1960s, there were a number of logs or benches in the grove that seemed to have attracted people and they felt that they had found the exact spot. I recall the bleachers that were set up nearby, and I attended a meeting or two or three or four here in the grove.

Enders: I myself sat there a good number of times.

Porter: With its flooring and wooden deck and the wooden pulpit.

Enders: With the sound system and lights.

Porter: In those days, those working in the grove were busy with their tree operation and snipping. If a tree base developed a problem and there was a space there, they cleaned out the space and filled it with cement. And Bob, I do not know if there are any cement trees left.

Parrot: No, thankfully we have no cement trees in the grove.

Holzapfel: Bob [Parrot], please provide us a brief history of your involvement in the Sacred Grove.

Parrot: Well, just as some background, I too have been walking in the grove since about 1961. As I became professional and began to look at it with a professional eye, I would often wonder, “What in the world are they doing here? Do they realize what they are doing to this forest?” The forest was essentially being manipulated in such an artificial way that it was open and parklike and almost sterile. There was almost a complete absence of indigenous species or wildflowers and plant life; there was no decaying woody material on the ground that would support and shelter chipmunks and wild turkeys and woodpeckers and songbirds and all the creatures that we would like in a forest.

Enders: Yes, even those animals were absent.

Parrot: Of course, I had no contacts with anybody until I was approached to assist in getting the logs out for the log home. In the course of discussions with the site director at the time, and eventually you [Don] and others that were involved, I learned that the Church was seeking to change course and implement a sound management policy for the grove that would restore the ecological balance and the fertility to the soil—also to make the grove look as wild and natural and as much like it may have looked in the 1820s as we could accomplish. Basically, the parties involved in the Church had a concept. Most of the concept was good, but some of it was not totally viable or desirable. For example, the Church envisioned an old grove forest, but we did not want strictly an old grove forest in there because an old grove forest is predominantly large, overmature trees that have a relatively short lifetime. There is an absence of viable regeneration in such forests. My job was to take the Church’s raw concept and to develop it into a workable and sustainable forest management program. That has been my privilege to do for the last twelve years or so.

Enders: What we know is that you have taken the approximate seven acres and helped us as a Church to catch the vision of what the woodland was like in the 1820s. And through regeneration the grove is expanding and will soon reach 150 acres.

Parrot: Well, that was one of the objectives of the Sacred Grove Conservation program, to restore the forest to the original size it was when Joseph went there. The First Presidency thought that it was not just a small patch of trees that Joseph went to for his vision. He went to a specific area perhaps, but it was part of an overall contiguous forest. One of our objectives is to restore the forest to its original size and appearance. This also allows for expansion of the grove trail system as the Church continues to grow. All the Church-owned area surrounding the original grove had been about seven acres. Then the Church acquired Hyrum’s hundred-acre property, and the grove became about thirteen acres of mature forest. That was all we had until about 1998, when additional forested areas were purchased and the grove expanded into them. All the former farmland and fields surrounding the grove are being allowed to regenerate naturally back into forest as well. We have regeneration that is as old as fifty years and areas that are as young as ten years. This area behind us, for example, is about thirty-five years of regeneration.

Enders: And all of this helps ensure that future generations, not only of Latter-day Saints but of all visitors, will have the opportunity to come in and quietly experience this woodland.

Porter: This is a very primeval forest. In that seven acres there are a number of trees, you have told us, that date back to the time of Joseph Smith. Would you like to indicate what is left of that early forest?

Parrot: We have six trees that we know to be well in excess of 200 years old. To be more exact, they are approximately 225 years old. We have one tree, of the six, that is probably between 300 and 350 years old. Because the dating process is not terribly precise, we consider those six trees to be the “witness trees” because we know that they are more than old enough to have been here at the time of the First Vision. But we also have perhaps another six or eight trees scattered throughout the grove that are somewhere between 180 and 200 years old. So, more than likely they were here at the time of the First Vision, although they were just seedlings. All the trees of that age are around the original hundred-acre portion of the farm.

Porter: Without enumerating all the kinds of trees—I know you have a list that I have looked at, and it is substantial—can you tell us what the primary trees were that existed here in the days of the Smiths?

Parrot: The forest environment that we have here now, I believe, is very similar to what was here in the Smiths’ time. From looking at the species that they used in the construction of their buildings, for example, we see that they used the same species of trees that we have now. There were probably a couple of species that were here then that are not here now, such as the American chestnut and the American elm, both of which were killed off by invasive species from overseas. But aside from that, I think that everything that was here then is here now. The dominant species in these forests are sugar maple, beech, basswood, ironwood, and hickory. Those are the dominant species in the forest now, although we have approximately thirty species of trees in and around the Sacred Grove.

Enders: Now tell us just a wee bit about the forest regeneration and the upper canopy, lower canopy, and ground covering.

Parrot: It has been since the implementation of the forest management program, which has basically been in the last decade, that any meaningful progress has been made. There has been a tremendous change in the appearance of the grove. It has become lush and green. There has been a return of indigenous species of wildflowers and plant life. The floor of the forest is mostly covered with green in the summer, whereas in the past it was just bare, brown leaves. There has been a tremendous increase in the regeneration of viable young trees, which is essential to the preservation of the grove. Trees do not last forever, just like humans, and we have to have replacements that grow. We strive for diversity of species in there so that we are not putting all our eggs in one basket; in case another invasive insect or disease comes in and wipes out a specific species, we have got plenty of other species there to take its place. The most rewarding aspect for me is to see the change in appearance. When we first started the program, of course, there was no downed organic material on the floor of the forest; everything was cleaned up and groomed and sanitized. Decaying organic matter from downed logs and that sort of thing is where the trees get their nutrients. That is why the forest was so lacking in natural vegetation and regeneration. When we first started leaving the downed logs, we would have visitors come in and complain that it looked messy—“It looks messy in there! You are not caring for the Sacred Grove!”—when in fact we were just beginning to care for the Sacred Grove. But now we have visitors who have returned after ten or fifteen or twenty years, unaware that we have implemented any change in policy, noticing the change. They often come in and ask and say, “I was here years ago, and now the forest looks so lush and green and healthy. Why is that? What is happened to bring about that change?” The fact that they recognize the change without knowing that we are striving for it shows that they are unbiased in their assessment.

Enders: So, what you are saying is that your work creates an atmosphere so subtle that folks have no idea what happens here. They do not even know that you have been at work.

Parrot: But they enjoy it, they appreciate it, and they like the appearance of the grove as opposed to what they saw before.

Porter: What protective measures have you put in place when the ice comes and the wind blows, or microburst hits—who is first on the job and looking at the grove?

Parrot: Well, one of our prime priorities here, of course, is the safety of the visitors to the site. The forest is inherently a dangerous place. Every tree has dead branches that can fall from the tops of the trees in windstorms and the like. Of course, severe catastrophic storms will bring down whole trees. We are very vigilant about that, and it is my job to monitor the weather conditions and close the grove whenever the winds exceed approximately forty-five miles per hour. I inspect the grove after such storms and take care of any hazards that may have developed. If we have a catastrophic storm, then I am busy in there for some time. Don was here when we had the last ice storm in 2003. The place was just devastated. But most of the material that went down in that storm (and we lost over a hundred trees) has since disappeared and decayed, returning to and enriching the earth. Only the large logs remain, and we want those. That is another one of our objectives, the old grove forest ambience. We are not striving for an old grove forest per se, but we want to incorporate as many of the features as we can, such as downed logs and moss and fungi, which we have an infinite variety of growing in the grove now. They were not here before because there was nothing for them to grow on. And the wildlife was not here before because there was nothing for them to live in and to feed on. The balance is returning to the grove, and the evidence is clear anywhere you look that it is very important that we stay the course. Nature is a long-term project. You cannot keep tinkering with it and veering off in other directions. So we are on track and need to stay on track and hopefully we will.

Standing in the Sacred Grove, discussing its history and caretaking are (left to right) Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Robert Parrot, Donald L. Enders, Larry C. Porter, and Kent P. Jackson. Photo by Brent R. Nordgren.

Standing in the Sacred Grove, discussing its history and caretaking are (left to right) Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Robert Parrot, Donald L. Enders, Larry C. Porter, and Kent P. Jackson. Photo by Brent R. Nordgren.

Holzapfel: Tell us briefly about the insects and animals that have returned. What have you observed?

Parrot: Well, there are a lot of insects that we do not even notice and we would consider unimportant, but the Lord put them here for a purpose, even if it is something as mundane as just breaking down a decaying log. All of that speeds the process. They bore through the log, making passageways where the water comes down and soaks through those passageways, and that speeds up the process of decay. In the meantime, there are wild turkeys, woodpeckers, and other birds that are more than happy to feed on these very insects that are breaking down or are living in the decaying organic matter. As the birds chop at the log or chew it apart to get at the insects, they also speed up the decay process. It is amazing that those things have returned so quickly because they were not here before. I knew what would happen over time when we initiated this program, but I never expected it to happen so quickly. Ten years is just a blink of an eye in nature’s time frame.

"We do everything we can to preserve the witness trees . . .because we cannot grow new trees." Pictured here next to a witness tree are (left to right) Larry Porter, Kent Jackson, Richard Holzapfel, and Don Enders. Photo by Brent R. Nordgren.

"We do everything we can to preserve the witness trees . . .because we cannot grow new trees." Pictured here next to a witness tree are (left to right) Larry Porter, Kent Jackson, Richard Holzapfel, and Don Enders. Photo by Brent R. Nordgren.

There has been a very noticeable and significant change in ten years. I feel that it is, in part, due to what we are doing, the good things that we are doing, and to the fact that we stopped doing the wrong things. I think it is, in part, a sign from the Lord saying, “There. You are on the right track. You see how nicely that works? Stay the course.” He guides us just as we would guide children who are doing something, perhaps attempting to drive a nail or use a handsaw or any number of things: if their technique is flawed, we direct them a little bit, show them how to do it, praise their efforts, and point out how much better the new way works. That is my feeling for what is taking place here.

Holzapfel: One of the themes developing in our conversation today is “return.” Bob, in addition to the return of the natural growth of the woodland and the insects, what else has changed?

Parrot: Well, for example, during the period prior to the program there was an infestation of garlic mustard, which is an invasive species of plant. I do not personally think that it does a great deal of harm, but it was something of concern to many in the Church, whether it was a problem or not. In the ten years since then, indigenous species like jewel weed have returned and have crowded out the garlic mustard. It is just nature restoring the balance as long as we get out of the way and do the right thing. Jewel weed is a wildflower that is very popular with hummingbirds, so we have hummingbirds now in the grove. There are jack-in-the-pulpits, trillium, evening primrose, mayapples, spring beauties, toothworts, and bellworts, and a whole spectrum of wildflowers has returned. All these things come about in sequence in the spring. Each flower has its brief period in the sun, perhaps a couple of weeks and then another flower gets its turn. So we have wildflowers of all varieties, and right now we have the late summer and early fall flowers. We get another indication about the health of the forest from the indigenous species we see and the environment we know that they grow in. Many of those species require moist fertile soil to live, so the fact that they are in there and have returned is an indicator that we now have moist fertile soil in the grove, and that is what we need.

Enders: Bob, please tell us your perspective about the early spring of 1820 and how that may relate to the First Vision. Tell us about the variableness of the season. What is the situation of most of the trees and the ground coverage at that time?

Parrot: Well, it is usually depicted in artists’ depictions as being lush green forest as Joseph kneeled and prayed. But if he went as early as we think he probably went, the forest was at best just beginning to green up. There may have been apples beginning to poke through, there were leeks (wild leeks are one of the first things to come up), and some of the trees may have been just starting to leaf out. But it is a very pretty time of year in the early spring before the leaves come out. The bugs have not arrived yet. The sun is very strong. It highlights and shines on the trunks of the trees and silhouettes the canopies of the trees against the blue sky. We have many beautiful sunny days with blue sky.

Enders: Truly the colors and textures of the tree trunks, branches, and canopies and the different species stand out very noticeably.

Parrot: It is no less beautiful than later in the year when everything is lush and green. It is a transition period, and it is alive and birds are singing, and it would have been a beautiful time to go into the forest.

Enders: What might the temperature range have been?

Parrot: It could have been as warm as the mid-seventies on occasion, but probably more likely in the fifties at that time of year—maybe low sixties. I also had a thought to follow up on your question, Larry. It is interesting because we tend to think of the grove, at least in the earlier years of the Church owning the property, as being just the part that was on the hundred-acre farm. We think, “Well, that must have been where Joseph went.” But, as I said, he went to a large forest. Perhaps it was to a specific spot, but it was part of a large forest, and as we have expanded the grove and expanded the trail system, and as you walk around through all the portions of the grove, the Spirit does not leave you. You do not suddenly cross a line and say, “Whoops, I am off of the sacred part.” The whole forest is sacred. Again, the objective of the Church was to restore the original size of the forest because the whole forest is where Joseph went and where the experience took place.

Holzapfel: Obviously, this is a special place for Latter-day Saints. However, does the restoration of these particular woodlands matter to anyone else? Bob, what do you think?

Parrot: It is a wonderful opportunity as a forest manager. My basic fundamental purpose is to grow forests and to keep them healthy. Of course, I have worked for many private clients, and you can do everything right for a private client, but then they die or sell the property and the new client calls in the loggers and in two weeks they have undone everything you did in fifteen or twenty years. But the Sacred Grove is always going to be the Sacred Grove. So here we have an opportunity for a really long-term forest management project, especially with these regeneration areas. We are starting totally from scratch here. We will be able to see forests start from their infancy all the way to maturity. When I take the young sister missionaries through on tours I tell them that, because in their lifetime they are going to see that transition. They are going to come back with their grandkids someday, and where it was weeds when they went through, it is going to be forest. So it is an amazing opportunity and an amazing thing to see.

Enders: What are your thoughts about how this program is progressing? Are we succeeding?

Parrot: Well, if we stay on course, we are going to succeed pretty well. But the forest is going to be a little different because of the environmental challenges. Fortunately, we still have witness trees, and we have trees that are in excess of two hundred years old. But I do not think we are going to see trees like that again. Trees will not live that long. Our best hope in preserving the Grove and maintaining some continuity of appearance is to keep it as healthy as possible, so it is better able to combat the environmental stresses that it is likely to encounter, and also we hope to encourage as much diversity as possible so that we are not putting all our eggs in one basket. We do everything we can to preserve the witness trees. As you know, I have fought, as have you, many a battle to safeguard them because we cannot grow new witness trees. We have the ones that were there, and that is all we have. But we will be able to grow large trees for future generations that give them the effect of the types of trees that were present in the Smiths’ time. We have trees now here that are not witness trees but are very large, and they still give the effect of the sorts of trees that the Smiths and other settlers would have encountered and would have had to deal with.

Holzapfel: Let me say in conclusion, thousands and thousands of people walk through this woodland and will never meet you, Bob. They will most likely never know your name. For many, it may never even cross their minds that somebody has been working here in the Sacred Grove.

I remember coming here for the first time in 1972 when I was driving from my home in southern Maine to the West Coast just before I left on a mission. Since that time I have returned on numerous occasions as a researcher, tour guide, and private visitor on a personal pilgrimage. At first I did not notice the transformation that was occurring, but soon it was apparent. I am amazed at the change that has occurred under your careful supervision. I can only thank you from the bottom of my heart for making this return to the Sacred Grove more meaningful. The Sacred Grove is not only a religious site but beautiful woodland. Your efforts have allowed me, my family, and countless others not only to reconnect with our sacred past but also to reconnect to nature—to the woodlands. You have performed a remarkable and hopefully lasting service to us all. The return to the Sacred Grove is an extraordinary story. Thank you for sharing it with us.