The First Institute Teacher

Casey Paul Griffiths

Casey Paul Griffiths, "The First Institute Teacher," Religious Educator 11, no. 2 (2010): 175–201.

Casey Paul Griffiths (griffithspc@ldschurch.org) taught at Jordan Seminary when this article was written.

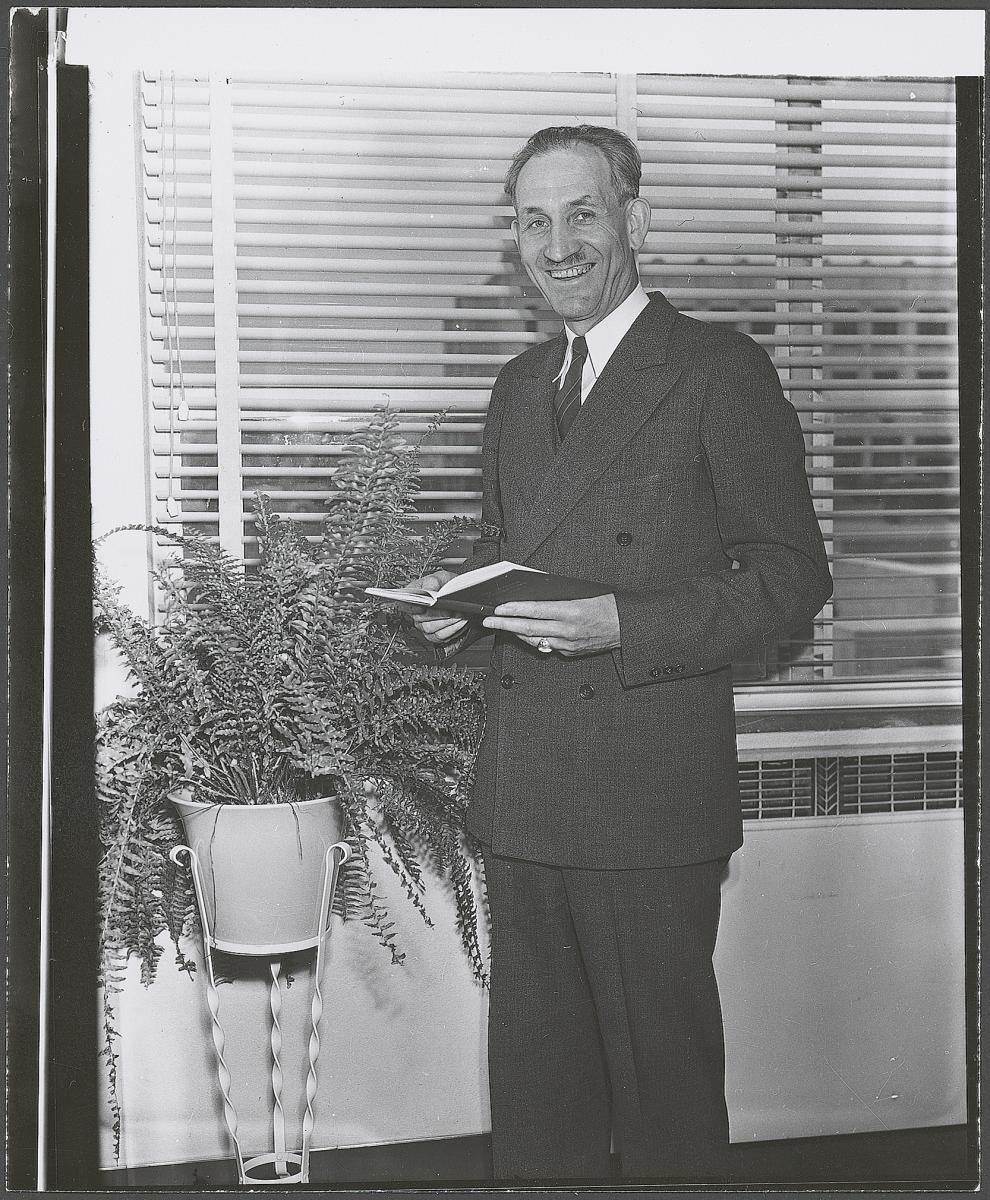

Upon returning from a seven-year mission to South Africa, J. Wyley Sessions (pictured here) was sent to Moscow, Idaho, where he started the first LDS Institute of Religion. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

Upon returning from a seven-year mission to South Africa, J. Wyley Sessions (pictured here) was sent to Moscow, Idaho, where he started the first LDS Institute of Religion. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

When J. Wyley Sessions walked into the office of the First Presidency in October 1926, he was sure that he knew exactly what they were going to say.[1] Returning physically exhausted and nearly destitute after a seven-year mission to South Africa, Sessions expected to find employment in the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company. He and his wife, Magdalene, had promised each other that they would not reenter the field of education. So it came as somewhat of a shock when in midsentence Charles Nibley, Second Counselor in the First Presidency, turned to Church President Heber J. Grant and abruptly announced, “Heber, we’re making a mistake! I’ve never felt good about Brother Sessions in the sugar business. He may not like it. There’s something else for this man.” After a moment of silence, Nibley looked directly at Sessions and said, “Brother Sessions, you’re the man for us to send to the University of Idaho to take care of our boys and girls who are attending the university there, and to study the situation and tell us what the Church should do for Latter-day Saint students attending state universities.” Sessions was not immediately enthusiastic about this new call and responded, “Oh no! I’ve been home just twelve days today, since we arrived from more than seven years in the mission system. Are you calling me on another mission?” President Grant spoke next: “No, no, Brother Sessions, we’re just offering you a wonderful professional opportunity. Go downstairs and talk to the Church superintendent, Brother Bennion, and then come back and see us about three o’clock.” Years later Sessions would recall his conflicted feelings upon leaving the meeting: “I went, crying nearly all the way. I didn’t want to do it. But just a few days later our baggage was checked to Moscow, Idaho, . . . and there [we] started the LDS Institutes of Religion.”[2]

This inauspicious beginning to the institute program typified the career of this unlikeliest of religious educators. Leaving Salt Lake City, Sessions recounted that the only instructions he received from President Grant were, “Brother Sessions, go up there and see what we ought to do for the boys and girls who attend state universities and the Lord bless you.” President Grant’s admonitions on that occasion echoed advice given when Sessions left on his mission to South Africa and, perhaps just as well as anything, capture the educational philosophy of J. Wyley Sessions: “Learn to love the people, nail your banner to mast, and the Lord bless you!”[3]

Answering the Lord’s Call

The call to go to Moscow was not the first surprising request Sessions and his family had received. Sessions’s role in the educational history of the Church was not one that he sought out; rather, it found him. Time and again, though he sought out professional opportunities in other areas, when the Lord’s call came, he sacrificed his own desires to respond. In the course of his lifetime of unintentional Church service he would serve as a mission president in Africa, found the first Latter-day Saint institute program, found two other institute programs, serve as president of the mission home, and end his career in Church education as head of the Division of Religion at Brigham Young University. All this from an individual whose original training was in agronomy! Sessions’s odyssey through the educational development of the Church in the early twentieth century not only richly illustrates the dynamic forces shaping the intellectual development of the Church at the time but also records the hand of the Lord in the life of a simple but obedient servant. Through each step in his journey, Sessions proved the far-reaching nature of the Lord’s vision in setting up the institutes of religion, which would shape the lives and testimonies of thousands of young Latter-day Saints. Each institute around the world owes something to the pioneering efforts of J. Wyley Sessions, the first institute teacher.

Learning to Answer the Call—South African Mission

Sessions’s first important call to Church service came in 1918. Working as a county agricultural agent for the University of Idaho, Sessions was preparing for a trip to vaccinate some cattle when his secretary arrived with a letter from the First Presidency of the Church. Sessions was only thirty-two, and he and the men working with him were somewhat suspicious as to the contents of the envelope. One of the men remarked, “Well, they’ve caught up with him now!” Sessions nervously opened the letter and read, “Dear Brother Sessions, We have decided to call you to preside over the South African Mission. . . . Please tell us how you feel about this appointment. Praying the Lord to bless you, we are sincerely your brethren, Heber J. Grant, Charles W. Penrose, and Charles W. Nibley.” Immediately struck by a sense of his own inadequacy for such a call, Sessions “cried about the first week, and swore the second week, and the third week I decided to go down and tell the Brethren that I just could not go.”[4]

On his way to Salt Lake to speak with the First Presidency, Sessions stopped in Preston, Idaho, where a stake conference was being held. The conference was presided over by Elder Melvin J. Ballard, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve. Wishing to avoid seeing Elder Ballard, Sessions deliberately went to the conference late, finding a seat on a staircase where he could see and hear but wouldn’t be seen by the authorities from the stand. He stayed there safely for the entire morning meeting without being noticed. Arriving late to the afternoon meetings, hoping again to remain incognito, he was shocked to find that someone in the crowd had informed Elder Ballard of his presence. He soon found himself being ushered to the stand.

Sessions later recalled that “when his time came to speak, he would inform the audience bluntly that his call was a mistake, that someone had provided the First Presidency with faulty information, and that those enjoying the ear of the Brethren should be more careful in the advice they offer.” When his time to speak came, as he approached the pulpit, Elder Ballard arose, took him by the arm, and proceeded to escort him the rest of the way. Elder Ballard then announced, “When President Grant nominated Brother Sessions to be President of the South African Mission in our meeting in the temple the other day, I could hardly sit still waiting for President Grant to get through with the nomination, so I could get up and second it! I think the Lord has some work for this man to do down there.” Elder Ballard offered some other kind remarks, and then it was Sessions’s turn to speak. He declared, “Brothers and Sisters, when any man advises a member of the General Authorities of the Church, he’d better be careful of what he says, for when these men speak after their meetings that they hold in the temple and under the inspiration of the Lord, they don’t make mistakes.” His mind racing, Sessions knew the words were inspired and were provided as a witness to the divinity of his call. With tears flowing, he announced to the audience his intention to go to Salt Lake City and accept the call.[5]

When he arrived there, his feelings of inadequacy again resurfaced. As he told President Grant that he wasn’t qualified, the Church President shot back, “You think we don’t know that? Of course you’re not qualified. None of us are. You ought to work for the Lord and depend on the Lord and he’ll qualify you.” Sessions later recalled, “That was all the comfort I got out of President Grant for my not being qualified. I was only thirty-two years of age.”[6]

South Africa, 1919–26

Sessions’s feelings of inadequacy were justifiable. Presiding over the South African Mission presented a number of challenges. His call sent him to the mission most distant from Church headquarters. In later years, he used to joke that any direction he went from South Africa, he would be closer to home![7] Sessions struggled even to gain entrance to Africa, because of the confusion resulting from the end of the First World War and the panic resulting from the worldwide influenza epidemic. After waiting several months for a visa, he was called to labor in California for several months before departing for England, where he again waited several months before finally leaving for South Africa. Having three different missionary farewells in eighteen months, the Sessionses finally found themselves on a ship headed for their destination.[8]

During the course of their journey to South Africa, the Sessions family endured serious trials. Magdalene Sessions was several months pregnant, and the hot, oppressive environment of the ship caused her deep discomfort. When the ship was ten days away from South Africa, she lost her baby and became critically ill herself. At one point she was so ill that several passengers asked Sessions if he was planning to bury his wife at sea, or take the body back to Utah. Deeply concerned, Sessions asked the captain of the ship to post a notice that Sister Sessions was not dead and was not going to die. Asked by the captain how he could be sure given her critical condition, Sessions responded, “I know she isn’t going to die, because the prophets of the Lord have blessed her that she won’t die,” referring to a blessing given to Magdalene earlier by Elder Ballard. Magdalene not only survived the journey but recovered fully almost immediately after their arrival in South Africa.[9]

Even as they disembarked, the Sessions received a taste of the hostility that existed in that country toward the Church. Before he was allowed to leave the boat, Brother Sessions was required to sign a document stating that he would not preach polygamy, take a plural wife, or break any of the laws of the country during his stay there.[10] Missionary work in South Africa was at a low point when the Sessionses arrived. Sessions’s predecessor, Nicholas G. Smith, had served in the area since 1914. During the world war, only four missionaries remained in the country, and in 1919 all Latter-day Saint missionaries were banned from serving in the country. Only President Smith and his family had served in the mission for the last two years before Sessions’s arrival.[11]

When Sessions arrived, he was the only official full-time missionary in South Africa. He later joked that he wrote to President Grant that he was having a terrible time disciplining the missionary force. The situation was discouraging, but Sessions immediately set to work, displaying the qualities that would later serve him as an institute director. Seeking to obtain legal status for the Church in South Africa, Sessions used his old connections in the Department of Agriculture to obtain letters of recommendation from the governors of Utah and Idaho, all four senators from both states, two college presidents, and the U. S. secretary of agriculture.[12] Sessions began networking, joining scientific societies, and even judging Holstein cattle in stock shows around the country. Over the course of his time in the country, he was able to receive official recognition for the Church and gradually increase the number of missionaries from zero to twenty-seven.[13] His warm, genuine nature won over people throughout the country, and letters from friends in South Africa are sprinkled throughout Sessions’s remaining papers.

Success in South Africa did not come without a cost. Writing home to his brother in 1925, Sessions counted the cost of his missionary service: “We are all well and feel contented to remain here as long as we are wanted. I confess it that sometimes when I look about me and realize that I am 40 years old and that I have less than I had when I was married it makes me want to get home and start again. I realize however the importance of this work and other matters sink into insignificance beside it.”[14] In 1926, when their release came, the Sessions family prepared to return home, expecting to pick up the threads of their old life. After seven years and three months in the mission field, a return to the field of agriculture seemed to suit both of them; however, the Lord had different plans.

Another Call to Serve

While the Sessionses continued their missionary labors in South Africa, momentous changes were occurring in Church education. In 1919, Adam S. Bennion was called as the Church superintendent of schools, and he, along with other leaders such as David O. McKay, and John A. Widtsoe, began a radical restructuring of the Church school system. For several decades the Church had maintained a system of loosely associated high schools (called academies) and colleges. Under Bennion’s direction, the Church began withdrawing from secular education in favor of a supplemental system of religious education. Beginning in 1920, the Church began closing the academies or transferring them to state control as quickly as possible.[15] To compensate for the loss of the academies, seminaries, many of which were already in operation, would be built next door to public high schools. In a meeting held in February 1926, Bennion suggested closing or transferring the Church’s junior colleges to state control as well. Some members of the Church Board of Education agreed with Bennion, and some did not. While Bennion saw the virtue of the Church colleges, he felt that the seminary system could be adapted to also serve on the collegiate level. Speaking directly of his own experiences at the University of Utah, Bennion recalled, “In the days when I needed help most that help did not come through any organization, but the two men who helped me the most in the University of Utah were Milton Bennion and James E. Talmage.”[16] Bennion suggested the Church provide mentors who could assist students in navigating the sometimes rough waters of academia while in college. He suggested the value of “a strong man who could draw the students to him and whom they could consult personally and counsel with,” saying that “such a man would be of infinite value.”[17] While no definitive policy emerged from the meeting, the questions raised by Bennion made two things clear. First, the finances of the Church and its continuing expansion simply would not allow the building of the number of colleges needed to serve all the members of the Church. Second, a new system was needed to meet the spiritual needs of the college-aged students.[18]

The idea of a supplementary system of education for college-aged students was not new. The Church had long held concerns that some of its brightest students were losing their faith while in college. An annual report of Church schools for 1912 noted that the University of Utah and several state schools saw a need for weekday religious instruction of their students. In 1915, Church superintendent Horace H. Cummings stressed concerns that students at the University of Utah were in need of religious education. He noted that the president of the university and several faculty members had urged the Church to establish a building near the campus for the purpose of religious education. They even offered college credit for such classes. While the concerns were noted, little action was taken for the next decade.[19] During Bennion’s tenure as superintendent, letters began arriving from Moscow requesting a Church student center near the University of Idaho. At a meeting of the Church General Board in 1925, Bennion proposed the possibility of a seminary and social center to be built in the area.[20] During this time a “Macedonian call for help” came from Moscow branch president, George L. Luke, a professor of physics at the university.[21] The situation was ripe for the initiation of a new system.

In the middle of all these movements, the Sessions family arrived home from South Africa. As mentioned earlier, Sessions fully expected to receive a position in the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company upon his return from South Africa. Before his meeting with the First Presidency and his call to go to Moscow, Idaho, he had already met with a representative from the company. In later reminiscences, Sessions mentioned he felt the issue was already decided because he had the endorsement of Apostle George Albert Smith and Charles W. Nibley of the First Presidency.[22] All of these factors may account for the shock he received when he was asked to go to Moscow.

Given his background, why was Sessions selected to go to start the institute program? After all, he had no training in the field of religious education. Teachers of religion were in no short supply at the time, due to the burgeoning new seminary system. Sessions possessed no schooling beyond a bachelor’s degree in agronomy—his academic credentials were certainly no reason for him to be called to establish a collegiate program. Sessions wrestled with his own lack of qualifications for the position, later noting, “I could do something about farm fertilizer, but I didn’t know anything about the Bible and religious teaching!”[23]

At the time, the call must have seemed an impulsive decision. However, looking deeper, there were unique factors that suggested Sessions might be the right person for the job. He had ties with the University of Idaho, having worked for them extensively before his mission call. His experiences in South Africa had demonstrated his ability for opening doors and making friends for the Church. The sacrifices that Sessions had made to serve confirmed his deep testimony of the gospel and his loyalty to the leadership of the Church.

Laying the Foundations—Moscow, Idaho

In many ways, Sessions’s assignment in Moscow was closer to missionary work than traditional religious education. As a native of the state, Sessions was aware of the cultural issues dividing the parts of the state settled by Latter-day Saints from parts settled by the rest of the population. Moscow was located in the northern part of the state, far from Mormon centers of strength, and the First Presidency had become deeply concerned about the spiritual apathy developing among the students there.[24]

While the members of the Church in the city welcomed Sessions and his family, factions of the community viewed them with suspicion. The imprecise nature of Sessions’s assignment in Moscow raised the level of distrust. The local ministerial association, some members of the university faculty, and several local business people even appointed a committee to keep an eye on Sessions and make sure that he didn’t “Mormonize” the university.[25] Realizing he needed community support in the new venture, Sessions set out to become a part of the town. He joined the local Chamber of Commerce, spoke to and later joined the Kiwanis Club, and both he and Magdalene enrolled at the university seeking master’s degrees.[26] Sessions used his affiliation with these organizations to reach out to people who otherwise wouldn’t have been willing to talk to him. At a series of biweekly dinners held by the Chamber of Commerce, Sessions made every effort possible to sit by Fred Fulton, head of the committee appointed to oppose his work. At one of these dinners, Fulton turned to Sessions and said, “You son-of-a-gun, you’re the darndest fellow. I was appointed on a committee to keep you out of Moscow and every time I see you, you come in here so darn friendly that I like you better all the time.” Sessions replied, “I’m the same way. We just as well be friends.” Sessions later reported that Fulton became one of his best friends during his stay in Moscow.[27]

Not all nonmembers in Moscow opposed Sessions’s arrival. In fact, a few became instrumental in helping to launch the institute. One of them, Jay G. Eldridge, professor of German language and literature,[28] even came up with the name for the new venture. Meeting Sessions as he walked past the construction site of the new building, Eldridge asked him what he planned to name the new structure. In most official correspondence to that point, the new buildings were referred to as “collegiate seminaries.”[29] When Sessions responded that he didn’t quite know what it would be called, Dr. Eldridge replied, “I’ll tell you what the name is. What you see up there is the Latter-day Saint Institute of Religion at the University of Idaho north campus.” He then pointed out that when his church built a similar structure it would be called Methodist Institute of Religion, and so on with other churches.[30] The suggestion was forwarded to Joseph F. Merrill, commissioner of education, who sent back a letter addressed to “the Director of the Latter-day Saint Institute of Religion—Moscow, Idaho.” When other institutes were founded, the name remained.[31]

Another nonmember who played a key role in the creation of the institute was C. W. Chenoweth, head of the department of philosophy. Chenoweth, a tall, pipe-smoking professor, was one of the most popular and respected leaders on campus.[32] Before his time at the university he had been a minister in a local congregation and had served as a chaplain during World War I. He became fascinated with overcoming the problem of teaching religious ideals and morals at state universities. Speaking to Sessions privately, he said, “If you’re coming on to this campus with a religious program, you had better be prepared to meet the competition of the university.” Intensely interested in the developing program, Chenoweth offered his assistance to Sessions. Together they studied the problems associated with launching a religion program adjacent to a university. Sessions wrote a term paper for his master’s program on the subject, later puckishly admitting that Chenoweth had personally dictated to him.[33] Sessions later invited Chenoweth to come and speak with him at Ricks College.[34] When Sessions was asked to leave Moscow to start an institute in Pocatello in 1929, Chenoweth wrote personally to the Church Commissioner of Education, asking for Sessions to stay in Moscow.

Developing the Philosophy of Institute

Winning over the community was only part of Sessions’s challenge. He was asked to create a new kind of religious education almost entirely from scratch. Anxious to receive some guidance in the venture, Sessions wrote to Brigham Young University, Illinois University, and several other universities. Worried over what the curriculum should be, Sessions wrote to Joseph F. Merrill seeking advice: “I have been working on a plan for the organization of our Institute and the courses we should offer in our weekday classes. I confess that the building of a curriculum for such an institution has worried me a lot and it is a job that I feel unqualified for.” Merrill’s reply two days later became a foundational pillar for the institute program. In Merrill’s mind, the objective of institute was to “enable our young people attending the colleges to make the necessary adjustments between the things they have been taught in the Church and the things they are learning in the university, to enable them to become firmly settled in their faith as members of the Church.” Merrill continued, “You know that when our young people go to college and study science and philosophy in all their branches, that they are inclined to become materialistic, to forget God, and to believe that the knowledge of men is all-sufficient. . . . Can the truths of science and philosophy be reconciled with religious truths?” A scientist by profession, Merrill wanted institute to be designed specifically to allow the reconciliation of faith and reason. To this end, he concluded, “Personally, I am convinced that religion is as reasonable as science; that religious truths and scientific truths nowhere are in conflict; that there is one great unifying purpose extending throughout all creation; that we are living in a wonderful, though at the present time deeply mysterious, world; and that there is an all-wise, all-powerful Creator back of it all. Can this same faith be developed in the minds of all our collegiate and university students? Our collegiate institutes are established as means to this end.”[35]

In constructing the institute curriculum, Sessions freely admitted that he “plagiarized” from several universities.[36] Some of his conspirators were university faculty from English, education, and philosophy departments who were just as eager to see how the new program would come into being. They sought out textbooks and outlines, assisting Sessions as he constructed several courses in biblical studies and religious history. Through an arrangement with the university, college credit was granted for each of the courses.[37] This arrangement meant that Sessions’s classes were occasionally visited by officials from the university. Speaking of this, Sessions would later recall, “If you think this fellow who had been teaching agriculture was not frightened, you’re mistaken!”[38] With the curriculum in place and with the support of the university, Sessions began teaching the first classes in the fall of 1927, roughly one year after his arrival. His total enrollment was fifty-seven students.[39]

In devising the institute program, Sessions was not just interested in offering religion classes. College-level religion courses had already been taught experimentally by Andrew Anderson and Gustive Larsen at the College of Southern Utah, beginning in 1925.[40] What distinguished Sessions’s efforts was his intention to launch an entire program designed to meet the spiritual, intellectual, and social needs of his students. To assist him in this endeavor, Sessions enlisted his wife, Magdalene, who devised a varied program of social and cultural activities.[41] Under the Sessionses’ supervision, the institute became an all-out effort to bring the scattered students into their own community at the university.

Reflecting on the role his wife played, Sessions later remarked, “If religion is anything, it’s beautiful, which is the philosophy that Magdalene worked with. . . . Nothing is more lovely than the teaching of Jesus, and Magdalene was putting religion to work. If religion is anything, it ought to serve us here and now. It ought to make our lives more beautiful, in more harmony. Now what did she do? She put the life and vitality and the beauty into the basic thing of religious education.”[42] Magdalene would play a key role not only in institute social programs but also in the decor and furnishing of each institute the Sessionses supervised.[43]

This fit in well with Sessions’s own philosophy of religious education. He wrote, “Religion is practical in life and living. It is not theory, but is absolutely necessary to a complete and well-rounded education. There can be no complete education without religious training. It must not, therefore, be crowded out, but a place for it must be left or made in an educational program and it must be kept alive, healthy, and growing.”[44] To Sessions, religion was not something that could be isolated. It needed to be a fully integrated part of everyday existence.

The First Institute Building

Sessions’s philosophy was reflected not only in the educational and social programs of the institute but also in the very design of the building itself. Not just a class building, it also featured a reception room, a chapel, a ballroom, a library, and a serving kitchen. The entire second floor of the building held eleven nicely furnished dormitory rooms, capable of accommodating twenty-two male students. The exterior of the building was done in the Tudor Gothic style of architecture, corresponding with the other buildings at the university.[45]

That Sessions was able to secure the funds to build such a structure was a miracle in and of itself. Locating a site on one of the main student thoroughfares to the campus, Sessions even secured the assistance of the local Chamber of Commerce to help with the cost of purchasing the lot. That Sessions was able to obtain these promises of assistance is a testament to his powers of persuasion, given the difficult economic conditions of the time. The Church elected to pay the full price of the building, but Sessions still had to negotiate with the First Presidency to secure the funds for the kind of building he wanted. Sessions also had to convince Commissioner Merrill, who he later described as “the most economical, conservative General Authority of this dispensation.”[46] Meeting with President Grant, Sessions said, “President Grant, I cannot go back to Moscow and build a little Salvation Army shanty at the University of Idaho.” Grant, cautious, replied, “If we give you $40,000, you will return and ask for $49,000 or $50,000.” Sessions then wryly commented, “President Grant, I promise you right now that I shall never ask you for $45,000 or $50,000, but I will not promise that I will not ask for $55,000 to $60,000.” Grant, smiling, answered, “Of course, the Moscow building must be nice.” A budget of $60,000 was allotted for the construction of the building. When the structure was completed, $5,000 was returned to President Grant, who remarked incredulously, “I did not think it possible or that I should live to see this occur.”[47]

Sessions wanted even the physical appearance of the institute to teach about the Latter-day Saints. He took as his motto, “If it’s the LDS institute, it’s the best thing on campus.”[48] He later reflected on his feelings that he wanted the building to “foster the idea that beauty is a good environment for religious stimulation, association, and general education.”[49] He declared with pride that “the buildings are used daily, almost hourly, by the students who enjoy and respect the privilege. An atmosphere seems to be cultivated which is often mentioned by even a casual visitor.”[50]

The Moscow institute building was dedicated on September 25, 1928, by President Charles W. Nibley.[51] It was fitting that President Nibley dedicate the building, since it was his inspiration that had sent Sessions to Moscow nearly two years earlier. Commissioner Merrill and other Church dignitaries also attended. In just a few short years the institute came to be widely respected on the campus. The program started by the Sessions began a tradition of excellence. During the 1930s, students living at the institute won the campus scholarship cup so often that they were eventually excluded from competition.[52] The institute was visited by others hoping to fashion a similar pattern. Ernest O. Holland, president of Washington State College, visited the building several times and remarked to several gatherings of educators that the institute program came nearer to solving the problem of religious education for college students than any other program he knew of.[53]

In 1929, Sessions was asked to leave to start a new institute in Pocatello, Idaho, while Sidney B. Sperry filled his position in Moscow. The decision appears to have caused a minor uproar in Moscow, prompting Commissioner Merrill to write to George Luke, a university professor and counselor in the branch presidency, to soothe his feelings. “Our request that Brother Sessions go to Pocatello is the highest compliment we can pay him. There is an extremely difficult situation there and we believe he is better qualified to solve it than any other man we have in our system.”[54] Luke wrote back, “I want to say candidly that I am not yet convinced that the move is a wise one.”[55] He wasn’t concerned with Sperry’s coming as much as Sessions’s going. Before the Sessionses left, a community celebration was held in their honor. Several hundred people attended, among them the mayor, all the officials from the university, and scores of local citizens.[56] In four years, Sessions had gone from being viewed as possible community menace to being one of the most beloved residents of Moscow.[57]

The Pocatello Institute

Sessions’s success in Moscow led to an assignment to open a new institute in Pocatello. In keeping with his philosophy of practical gospel application, Sessions quickly established a regimen of classes. In addition to traditional courses in the Old and New Testaments, less conventional courses were offered, like “Problems in Modern Religious Thinking” and “Church Practice and Religious Leadership.” The first of these two courses was open to all students of the university. The course description advertised it as a forum for students “to discuss and, if possible, solve their own religious difficulties.” The second course was described in the institute circular as “a laboratory course with actual experience in church work.” [58] Students were given specific assignments at the institute, local seminaries, and wards in the Pocatello Stake. On a weekly basis they consulted with Sessions about their progress in each area.

While Commissioner Merrill’s letter indicated an “extremely difficult situation”[59] in Pocatello, Sessions recalled the problems he faced there were largely similar to the ones he had tackled in Moscow. For the most part the problems facing the Moscow program would have only been magnified in Pocatello, where there was a larger LDS population and greater fears about the university being “Mormonized.” Once again Sessions opened doors through his affiliations with prominent figures of the community, most of whom were not members of the Church. F. J. Kelly, president of the University of Idaho, became a strong supporter of the institute, similar to Dr. Chenoweth in Moscow, and even gave a series of addresses to Latter-day Saints. As much as Sessions wanted to win respect for the institute, he also felt strongly that the local Saints should know that there were some “awfully good men at the University of Idaho and at Pocatello.”[60] To this end, he went to great lengths to give Latter-day Saints a positive impression of school officials who were of other faiths. At the dedication of the Pocatello building, Kelly, unable to attend, sent a letter to be read during the service. In it he called on “all the great churches” to provide religious education for their university students and called such institutions “an intrinsic part of the educational scheme.”[61]

Sessions’s existing correspondence from the period gives a window into his relationship with his students. To one returned missionary he advised, “You must be big enough now to reach out into the avenues of life and make wholesome contributions in every one of them.”[62] Not only did Sessions continue to advise past students, in some cases he was required to intervene for the well-being of prodigal children who were hundreds of miles away from their families. One case might serve as an illustration. In 1935, Sessions received notice of a BYU student who had been involved in a series of infractions beginning with petty theft and finally leading up to a series of stolen automobiles. While visiting a friend in Pocatello, the student was arrested and put into jail. Alerted by a call from one of the boy’s professors at BYU, Sessions went to visit him, though he had no prior knowledge of the boy or his family.[63] Learning that the boy was the only son of a widowed and ailing mother, he offered to serve as the boy’s parole officer, took him into his own home, and used his connections with the Pocatello Rotary Club to find work for him during the summer months.[64] During this time Sessions and the young man became so close that the boy took to calling him “Dad” in his letters.[65] Sessions’s correspondence from the period reveals a caring, sometimes stern relationship as he guided the student through the peaks and troughs of his recovery.[66] The final two letters in the collection, dated several years later, are from the young man, then serving a mission in the eastern United States.[67]

The Laramie, Wyoming, Institute

In September 1935 Sessions found himself in the office of John A. Widtsoe, who was then serving as Church commissioner of education. In the meeting Widtsoe asked Sessions if he would be willing to go to Laramie, Wyoming, to start another institute. Sessions’s response indicates his growth as a disciple since his call to Moscow, nearly a decade earlier. He replied, “Oh, dear. Oh, I wouldn’t like to go, but if you say I should go, I’ll go. You know my ability better than I do. And if there’s where I can serve best, that’s where I want to go. I don’t care where it is.”[68] Widtsoe then showed him a letter from A. G. Crane, president of the University of Wyoming, personally requesting that Sessions come and establish an institute in Laramie. Sessions had been recommended by President Kelly of the University of Idaho, a close friend of Crane’s.[69]

The arrival of Sessions and the construction of the institute were a major boon to the Saints in Laramie. Prior to the construction of the institute, Church members had been meeting in a local hall that had to be cleared of cigarette remains every week before services. Members were unable to donate much financially, but they contributed many hours of labor to its construction.[70] Supervising construction of an institute for the third time, Sessions directed the effort confidently, emphasizing the need for “utility, beauty, and adaptability” in the building’s design.[71]

The dedication of the Laramie institute featured an impressive array of guests. Present were President Heber J. Grant, the governor of Wyoming, the state commissioner of education, chief justice of the State Supreme Court, President Crane, and host of officials from the university. Dr. Crane held a dinner in honor of President Grant and the other officials who had come. Sessions remembered, “President Grant was so elated over it that he got humorous and told a number of very interesting stories which won the admiration of all the people who attended.”[72] Grant was so moved by the occasion that he mentioned the occasion in his opening address at general conference a week later, stating “there was a spirit of fellowship and good-will existing there the equal of anything I have experienced in my life.”[73]

Developing interfaith relations was one of Sessions’s hallmarks in Laramie, as it had been in Moscow and Pocatello. Referring to the institute, one local nonmember remarked, “Three years ago, very few people in Laramie were aware that Mormons live here, and if they did know they had no idea what the Church really stood for. . . . As one man said to me, ‘I didn’t even know there were any Mormons in Laramie, and suddenly they spring up all over the town.’ He was exaggerating, of course, and yet the importance of the Church had increased one-hundred fold with the building of the institute.”[74] After a chilly initial reception in Moscow and Pocatello, the institute program was welcomed in Laramie with open arms. However, Sessions was only to remain in Laramie for one year. His next call would remove him from the classroom and place him in a different environment altogether.

The Mission Home

At the end of the 1935–36 school year Sessions received notice from Church Commissioner Franklin L. West that he would be relocated again, this time to start another institute in Tucson, Arizona.[75] While in the midst of preparation for the move, a letter arrived from the First Presidency calling him and his wife to serve as the heads of the mission home in Salt Lake City.[76] The call came as a major shock. After ten years of single-minded devotion to the institute program, they would be leaving almost as suddenly as they had come. After writing his acceptance letter, Sessions wrote down a few reflections upon receiving this call. “Our hearts are sore today as we contemplate [the] severing of our connection with this great work. If I would consult my own feelings at this moment, and if I dare say so, I would say that it is a mistake to move us, but I shall follow the teachings of my Father and place myself in the hands of God’s service and say that I am willing to serve wherever and in whatever capacity my feeble efforts can most effectively be used.”[77] While he may have entered reluctantly into the institute program, Sessions was now heartsick at having to leave it. However, his reflections on leaving the system should not denote any hesitance on his part to take on the challenge. On the same paper in which he recorded his feelings of doubt, he also outlined a seven-point plan to improve the function of the mission home.[78]

The mission home in Salt Lake City grew out of efforts to prepare young people leaving to serve as full-time missionaries. The training was meager by today’s standards, with all missionaries staying for roughly ten days, regardless of their call. The rigorous schedule, combined with his frustrations over how the training was conducted, prompted Sessions to call his time in the mission home, “the hardest job we ever had.”[79]

The regimen at the mission home was intensive, with the day starting at 6:00 a. m. and running throughout the day with little free time.[80] Sessions’s initial plans to change the training for the missionaries were surprisingly similar to missionary training today. He wanted missionaries to have “more ability through experiences in logical thinking and discussion, instead of memorized, hackneyed terms, quotations, and passages.”[81] To this end he established a regimen of classes that included “public speaking,” “social demeanor,” and “harmony of science and religion.” In many ways, the curriculum implemented by Sessions was similar to his regimen for the institutes. Sessions’s ambitious agenda proposed lengthening the missionaries’s stay from two weeks to six months, a request that was not granted.

Despite his frustrations, there were many rewarding aspects of the calling. Sessions cherished his affiliations with the young missionaries. Among the hundreds of missionaries who passed through the mission home during Sessions’s time were two future Apostles, Joseph B. Wirthlin and Marvin J. Ashton, arriving within a few weeks of each other in March 1937.[82] Ashton even wrote back to Sessions en route to England, saying that he “learned more, and was influenced by a finer spirit” during his stay at the mission home than during any other time in his life.[83]

The mission home also afforded Sessions a marvelous opportunity to build relationships with the leadership of the Church. Missionaries were usually set apart personally by members of the Quorum of the Twelve. High-ranking Church officials frequently taught at the mission home. Records from the time show that members of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve often taught the missionaries personally.[84] Associating with many of the General Authorities allowed the Sessionses to experience life in the heart of Church headquarters. It would also play a vital role in a future assignment the Sessionses would receive. While their time at the mission home was productive, it was also brief. As had been shown, the Sessionses’ varied talents meant they would never stay in the same place too long.

The Division of Religion

Even during their stay at the mission home, the Sessionses were never completely withdrawn from the institute program. In spite of the rigorous demands of their calling, they still found time to travel to Arizona several times to supervise the construction and decor of several new institutes.[85] They were never officially “out” of the department of education but were merely on leave to the mission home. After two years, the Sessions were released from their call at the mission home and sent to the Logan institute. David O. McKay of the First Presidency explained that their call was originally intended to be for three years, but conditions in the department of education warranted his early release. What exactly these conditions were remain unclear.[86]

Upon his arrival in Logan, Sessions found himself in what was to him a novel situation. For the first time in his career, he was not pioneering a new institute; instead he was serving in the well-established program that had been headed by Thomas Romney for nearly a decade. Instead of serving alone, he was placed with three other capable teachers.[87] The move must have seemed like a vacation after his former labors. However, it would prove to be more of a short sabbatical before Sessions was sent to the final, and perhaps most controversial, phase of his odyssey in Church education.

During a campus visit to Logan in March 1939, John A. Widtsoe called Sessions and asked if he would join him for a drive. While they were in the car, Widtsoe informed him that the Church Board of Education was meeting that day, and while he would be absent, he knew what action they were about to take. The board had chosen to send Sessions to Brigham Young University to head the religion program there.[88] Sessions would later call this position the “top assignment” of his life.[89]

Arriving at BYU, Sessions experienced an entirely different kind of opposition from what he had faced in his prior assignments. Instead of having to win over a community, Sessions would have to win over his colleagues in the new Division of Religion. Most concerns raised were not with Sessions personally, but with his academic credentials and the decision to place him at the head of the division.[90] Most of the men in the division already had doctoral degrees, something that Sessions lacked. He had obtained a master’s degree during his stay in Moscow and had spent several summers at the University of Chicago working toward a PhD, but his intensive work with the institutes and other assignments had simply prevented him from advancing any further. Sidney B. Sperry, one of the professors at BYU, wrote to John A. Widtsoe, expressing his dismay that “another man is to come in as the head of the department of Religious Education who has had little or no real rigorous training as a number of us have. He is a fine fellow and we give him our support despite our personal feelings, but it hurts the morale of the department to have men hoisted over our heads when we have gone through the heat and labor of the day.”[91] Sperry’s feelings may have been injured because he felt that the Brethren were questioning the orthodoxy of the religion department by sending an outside man in. He may also have harbored legitimate concerns about the university’s accreditation with a non-PhD heading a university division.

While Sessions’s academic credentials were not insignificant, the question does beg to be asked, why was he sent to BYU? The answer in part lies with the complex development of the religion department at the school. From the beginning of the school until 1930, religion classes were taught by faculty members from all disciplines, with no specific teachers in the field of religion. While Joseph B. Keeler, George H. Brimhall, and others had borne the title of “professor of theology,” a review of their teaching load and other assignments reveals that they were not full-time religion teachers. The first full-time religion teacher at BYU was Guy C. Wilson, who arrived in 1930, just nine years before Sessions’s assignment. He was joined two years later by Sperry, the first religion teacher with a doctoral degree.[92]

Throughout the history of the school, the problem of how a religion department should operate was particularly nettlesome.[93] While allowing members of the different departments to teach religion demonstrated the integration of gospel principles into everyday life, it also prevented the Church from developing its own experts in the field of religion. Efforts to remedy this began in the 1930s, when Commissioner Merrill sent some seminary and institute teachers to the East for advanced training. Elder Boyd K. Packer offered his assessment on the effect of this training on some of the young men sent. “Some who went never returned. And some of them who returned never came back. They had followed, they supposed, the scriptural injunction: ‘Seek learning, even by study and also by faith’ (D&C 88:188). But somehow the mix had been wrong. For they had sought learning out of the best books, even by study, but with too little faith.”[94] Not all of the returning teachers were affected. Sidney Sperry and T. Edgar Lyon, two of their number, were among the most dedicated educators in the Church. Concerns over orthodoxy among Church educators even prompted President J. Reuben Clark Jr. to give the classic address, “The Charted Course of the Church in Education,” just a year before Sessions was sent to BYU.[95]

These issues were colliding with other concerns among Church leadership that BYU students were graduating with little serious scriptural or doctrinal study.[96] Consideration of these factors gives two possible explanations for Sessions’s sudden assignment to BYU. First, Sessions’s long record of accepting difficult calls, combined with his close affiliation with Church authorities during his tenure at the mission home, would have made him a trusted asset. Second, the questions surrounding how religious education should be conducted at BYU may have prompted Church leadership to consider trying to adapt the model established in the institute program on the campus. Sessions was the most experienced at this, so he was given the call.

Despite these factors in his favor, the transition to BYU was difficult. A sense of inadequacy in his academic credentials had nagged at him throughout his career, and at no time was it felt more intensely than his arrival at BYU. He later recalled, “I didn’t have a doctor’s degree. Most of the men at the head of the Religion Department are up in the upper brackets. . . . They had a difficult time.”[97] There were a few heated discussions about how the new division would be managed. Sperry wrote to a friend of a “terrific battle” a few months after Sessions’s arrival in which “the commissioner and his ally down here [presumably Sessions] took a terrible beating, the likes of which I have never seen in my life.”[98] Still, the battles fought in the department were productive, and a plan was hammered out for how the division would be organized. Sessions was appointed head of the division, with Sperry directing the Bible and modern scripture section, Wesley P. Lloyd heading Church organization and administration, and Russel B. Swensen leading the Church history section. Sessions also led the theology section.[99]

When the Division of Religion was fully organized, its work was much different than that of the current School of Religious Education. The university’s Board of Trustees directed it to be “a general service division to all university departments in the field of religious education.” In addition to this, the department was responsible for “all religious activities on campus,” including devotionals, Sunday School, and the Mutual Improvement Association.[100] During his time there, Sessions’s work at BYU was very similar to what he had carried out in the institute program. He later stated, “My institute experiences in other institutions where I had been had fixed in my mind rather positively at what an institute program should be and I was insisting on that.”[101] Sessions and his wife also organized a chapter of Lambda Delta Sigma, the LDS fraternity, on campus and initiated another series of cultural programs.[102]

Perhaps the most important duty Sessions carried out during his time at BYU was to build a permanent home for religious education. Sessions was initially asked by Commissioner West to design an institute building to serve thirty-five hundred to four thousand students. Sessions, still consulting on the construction of various institute facilities, originally thought the building would serve the University of Utah.[103] Shortly after his arrival in 1939, construction began on the original Joseph Smith Building. Construction of the building was conceived as a massive Church welfare project, with bishops from local ward securing the necessary workmen. When it was completed, the building adhered closely to the pattern established at Sessions previous posts, complete with an auditorium, a ballroom, a banquet hall cafeteria, even a “club room” for members of the faculty.[104]

The design for the building reflected Sessions’s earnest desire to provide a home away from home for students. Sessions would later relate that the source of his greatest anxiety during his time at BYU was “the absence of an ecclesiastical unit to serve students as a religious home.”[105] The Division of Religion found itself in a somewhat awkward position, finding itself in charge of the religious activities of the campus, but with no ecclesiastical structure for the students, who attended local wards. Sessions grew deeply concerned that students without local ties were engaging in almost no religious activity. In a survey conducted at the time, only eleven out of ninety-two students attended the First Ward, and conditions were similar or worse in the other wards.[106] An investigative committee recommended an institute be organized with a full priesthood structure to engage the students. A few years later, student branches were organized on campus, a move applauded by Sessions.[107]

In 1947, Sessions submitted his resignation to Howard S. McDonald, president of BYU.[108] His reasons for doing so were always fairly vague, though he later pointed to his concerns over President McDonald’s efforts to establish a “College of Religion,” something Sessions was opposed to.[109] Defending his opposition, he related, “We don’t have to a have a degree in Mormon theology. Every man ought to have that. . . . Religion needs to be taught everywhere and it needs to have the support of everybody.”[110] When Sessions realized that the program would change to a college set up, he chose to leave the university.[111] Sessions was replaced by Hugh B. Brown, who took over as head of the Division of Religion. In 1949, the position was discontinued when the new student branches took over the social programs of the division. Sessions’s recollections of leaving BYU were bittersweet, but he always retained warm feelings for the school. Nearly fifteen years after his resignation, he reflected, “It was evident that it needed something more than I could possibly give it, and it got it, and it’s going on.”[112]

“A Church Home away from Home”

Sessions spent the remainder of his life working in private enterprises. Though he no longer taught professionally, he retained a close affiliation with BYU, even participating in the search for a new president for the university after McDonald departed.[113] He found some measure of financial security, working mostly in real estate. In 1965, nearly eighteen years after his resignation from BYU, he made the decision to retire in Southern California. Before he departed, Richard O. Cowan, a member of his Provo ward and a religion professor at BYU, asked him to sit down and record his story.

In his interview with Cowan, Sessions’s warm teaching personality shines through. At age eighty he still retained a sharp memory of events. On the recording, his voice was still strong, modulating pitch and tone as he shifted from one moment relating a humorous anecdote to sharing a family tragedy. One can imagine what a student would have experienced in his early institute classes, with the witty aphorisms mixed in with deep spiritual insights. Sessions’s voice almost always sounded as if he were on the edge of laughter except when he bore testimony. Throughout the recording he can hardly be kept from transitioning naturally into his witness of the gospel and its power in his life. After two decades outside of the classroom, he was still passionate about the subject. “All that we teach—if we don’t get off on ritualism, and emotionalism, and extreme dogmatism, and make Latter-day Saint theology phony and thin and ludicrous—if we stay with the basic things, and teach the great principles of the Gospel, that will sustain the student when he goes out into this rapidly changing world.”[114]

Today over 150,000 institute students are taught at over five-hundred different locations.[115] The mixture of spirituality, social interaction, and service pioneered by Sessions is still present. Institute was a key factor in the outward expansion of the Church, allowing Latter-day Saints the peace of mind of knowing that wherever their children chose to receive their higher education, it would be supplemented by spiritual learning. Sessions brought the right blend of teacher, missionary, and community organizer that the institute program needed to find success. His legacy today is found in the thousands of institutes providing exactly what he set out to give in Moscow in 1926, “a church home away from home.”[116] These homes are perhaps the greatest tribute to one who frequently gave up the security and comforts of his own homes to answer the Lord’s call.

Notes

[1] Sources for this study came primarily from the J. Wyley Sessions Collection (Papers, 1911–1978, UA 156) at L. Tom Perry Special Collections Library in the Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, and sources at the Church History Library in Salt Lake City. Sessions documented his story in several oral histories, which can be found at BYU and in Church Archives. In addition to this, I am deeply indebted to Dr. Richard O. Cowan of the Religion Department at BYU for graciously allowing the use of an audio interview he recorded with J. Wyley and Magdalene Sessions in June 1965 to write this study.

[2] James Wyley and Magdalene Sessions Interview, interviewed by Richard O. Cowan, June 29, 1965, transcript and audio recording in author’s possession, hereafter designated as Sessions 1965 oral history; James Wyley Sessions interview, interviewed by Marc Sessions, August 12, 1972, MS 15866, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, hereafter designated as Sessions 1972 oral history. See also Leonard Arrington, “The Founding of the L.D.S. Institutes of Religion,” Dialogue 2, 2 (Summer 1967): 140; Ward H. Magleby, “1926— Another Beginning, Moscow, Idaho,” Impact (Winter 1968): 22.

[3] Sessions 1965 oral history, 9.

[4] South Africa Mission History Sketch, Sessions Collection, UA 156, Box 2, Folder 4, BYU Special Collections; spelling and punctuation modernized.

[5] South African Mission History Sketch, BYU Special Collections.

[6] South African Mission History Sketch, BYU Special Collections.

[7] Sessions 1965 oral history, 3.

[8] In his 1965 oral history, Sessions reports waiting eight or nine months for a visa before going to California, then staying in England for ten weeks before beginning his journey to South Africa. While the dates may not be exact, the Deseret Evening News reports Sessions receiving his initial call in late July 1919 and his call to California in April 1920. His departure for Africa is mentioned in the Improvement Era in March 1921. If these sources are accurate, it would mean that Sessions’ wait to arrive at his field of labors was even greater than the nine months he recalled between his call and his departure to California, and eleven more months before his departure for South Africa. “Elder J. Wiley Sessions Going South Africa,” Deseret Evening News, July 30, 1919; “Can’t Get Passport, So Missionary Will Labor in California,” Deseret Evening News, April 30, 1920; “South Africa and President Sessions,” Improvement Era, March 1921.

[9] South Africa Mission History Sketch, Sessions Collection, UA 156, Box 2, Folder 4, BYU Special Collections.

[10] South Africa Mission History Sketch, Sessions Collection, UA 156, Box 2, Folder 4, BYU Special Collections.

[11] South Africa Mission History, MS 16647, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, 1971, 2.

[12] South Africa Mission History Sketch, J. Wyley Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 4, BYU Special Collections.

[13] Sessions 1965 oral history, 3.

[14] J. Wyley Sessions to Elden Sessions, Johannesburg, South Africa, June 5, 1925, in Papers 1911–1978, Sessions Collection, Box 1, Folder 1, BYU Special Collections.

[15] Kenneth G. Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion: Superintendent of LDS Education, 1919–1928” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1969): 55.

[16] Church Board of Education Minutes, March 18, 1926, cited in Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion,” 89–90.

[17] Church Board of Education Minutes, March 18, 1926, cited in Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion,” 89–90.

[18] During the February 1926 meeting, President Heber J. Grant perhaps best summarized the situation driving these changes. He said, “I am free to confess that nothing has worried me more since I became president than the expansion of the appropriation of the Church School system.” See Bell, 91.

[19] William E. Berrett, A Miracle in Weekday Religious Education (Salt Lake City: Salt Lake Printing Center, 1986), 47–48.

[20] Berrett, A Miracle in Weekday Religious Education, 48–49.

[21] Leonard J. Arrington, “The Founding of the LDS Institutes of Religion,” Dialogue 2, No. 2, (Summer 1967): 140.

[22] Sessions 1965 oral history, 8.

[23] Sessions 1965 oral history, 10.

[24] Sessions 1965 oral history, 9.

[25] Sessions 1972 oral history, 5.

[26] Magleby, “1926—Another Beginning,” 23. Sessions 1965 oral history, 13.

[27] Sessions 1972 oral history, 5, 1965 oral history, 13.

[28] Moscow Institute of Religion (Idaho), Sixty Years of Institute: 1926–1986 (1986) Church Archives, CR 102 205, 4.

[29] Bell, “Adam Samuel Bennion,” 93.

[30] Sessions 1965 oral history, 12.

[31] Magleby, “1926—Another Beginning,” 27.

[32] Rafe Gibbs, Beacon for Mountain and Plain: The Story of the University of Idaho (Moscow: University of Idaho, 1962), 143.

[33] Sessions 1965 oral history, 11.

[34] Sessions 1972 oral history, 7–8.

[35] Magleby, “1926—Another Beginning,” 31–32. As one of the first native Utahns to obtain a PhD, Merrill was intimately familiar with the struggles he describes in his letter. He experienced them himself as a young man as he attended John Hopkins University. See Casey P. Griffiths, “Joseph F. Merrill: Latter-day Saint Commissioner of Education, 1928–1933” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2007), 24–30, and Joseph F. Merrill, “The Lord Overrules,” Improvement Era, July 1934: 413, 447.

[36] Sessions 1965 Oral History, 12.

[37] The arrangements in full may be found in J. Wyley Sessions, “The Latter-day Saint Institutes,” Improvement Era, July 1935: 412–13. Among the arrangements was a provision that “No instruction either sectarian in religion or partisan in politics” be taught in the courses. With similar arrangements made for other early institutes, this may help explain why such prominent LDS subjects as the Book of Mormon were not taught in the early days of the institute program. Noel B. Reynolds, “The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon in the Twentieth Century,” BYU Studies, 38, no. 2 [1999]: 28–29.

[38] Sessions 1965 oral history, 12.

[39] Sixty Years of Institute, 5.

[40] A. Gary Anderson, “A Historical Survey of the Full-Time Institutes of Religion of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1926–1966,” (PhD diss., Brigham Young University, 1968), 44.

[41] Sixty Years of Institute, 5.

[42] Sessions 1965 oral history, 16.

[43] Sessions 1965 oral history, 14.

[44] Sessions, “The Latter-day Saint Institutes,” 412.

[45] Sessions, “The Latter-day Saint Institutes,” 414.

[46] J. Wyley Sessions to Ward H. Magleby, Jan. 6, 1968, Laguna Hills, CA, Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 5, BYU Special Collections.

[47] J. Wyley Sessions to Ward H. Magleby, Jan. 6, 1968.

[48] Sessions 1965 oral history, 11.

[49] Sessions, “The Latter-day Saint Institutes,” 415.

[50] Sessions, “The Latter-day Saint Institutes,” 415.

[51] Magleby, “1926—Another Beginning,” 32.

[52] “Sharing the Light: History of the University of Idaho LDS Institute of Religion, 1926–1976,” 3. Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 6, BYU Special Collections.

[53] Arrington, “The Founding of the L.D.S. Institutes,” 143.

[54] Joseph F. Merrill to G. L. Luke, Salt Lake City, May 22, 1929, Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 5, BYU Special Collections.

[55] G. L. Luke to Joseph F. Merrill, June 3, 1929, Moscow, Idaho, Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 5, BYU Special Collections.

[56] Sessions 1972 oral history, 9.

[57] According to Thomas G. Alexander, Sperry did experience some difficulty in establishing himself at the institute and left in 1931 (Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890–1930 [Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1986] 169).

[58] Pocatello Institute Circular, Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 7, BYU Special Collections.

[59] Merrill to Luke, May 22, 1929, Sessions Collection.

[60] Sessions 1972 oral history, 9.

[61] Anderson, “Historical Survey,” 65.

[62] J. Wyley Sessions to Lorin D. Daniels, Pocatello, Idaho, December 12, 1931, Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 7, BYU Special Collections.

[63] William Anderson to J. Wyley Sessions, April 25, 1935, Pocatello, Idaho, Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 7, BYU Special Collections.

[64] J. Wyley Sessions to John A. Widtsoe, May 17, 1935, Pocatello, Idaho, Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 7, BYU Special Collections.

[65] William Anderson to J. Wyley Sessions, May 9, 1935, Boise, Idaho, Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 7, BYU Special Collections.

[66] Nearly the entire folder of Sessions papers from the Pocatello Institute consist of Sessions’ letters to William Anderson and his legal dealing on the young man’s behalf. See Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 7, BYU Special Collections.

[67] William Anderson to J. Wyley Sessions, Oct. 19, 1939, Maysville, KY; William Anderson to J. Wyley Sessions, January 6, 1940, Martinsville, Virginia; J. Wyley Sessions to William Anderson, January 15, 1940, Provo, Utah, Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 7, BYU Special Collections.

[68] Sessions 1972 oral history, 9.

[69] Sessions 1972 oral history, 9–10; “Institute Directors Named,” Deseret News, Sept. 11, 1935.

[70] Anderson, “Historical Survey,” 79–80.

[71] J. Wyley Sessions to Frank L. West, April 17, 1936, Laramie, Wyoming, Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 8, BYU Special Collections.

[72] Sessions 1972 oral history, 10.

[73] Conference Report, April 4–6, 1936, 11.

[74] Lorene Pearson, “The Institute at the University of Wyoming,” Relief Society Magazine, cited in Anderson, “Historical Survey,” 81.

[75] J. Wyley Sessions to Franklin L. West, April 17, 1936, Laramie, Wyoming, Sessions Papers, UA 156, Box 2, Folder 8, BYU Special Collections.

[76] First Presidency to J. Wyley Sessions, May 9, 1936, Salt Lake City, Sessions Papers, UA 156, Box 3, Folder 2, BYU Special Collections.

[77] This letter is attached to Sessions’s copy of his reply to the First Presidency. Apparently it was not sent and it addressed no one except Sessions himself (Sessions Collection, UA 156, Box 2, Folder 2).

[78] This letter is attached to Sessions’s copy of his reply to the First Presidency. Apparently it was not sent and it addressed no one except Sessions himself (Sessions Collection, UA 156, Box 2, Folder 2).

[79] Sessions 1965 oral history, 14.

[80] Missionary Preparation Training Course, Sessions Collection, Box 3, Folder 6, BYU Special Collections.

[81] Sessions letter, UA 156, Box 2, Folder 2.

[82] Mission Home Register, March 1, 1937 to March 18, 1937 (Wirthlin) and March 29, 1937, to April 15, 1937 (Ashton), Sessions Collection, Box 3, Folder 4, BYU Special Collections.

[83] Marvin J. Ashton to J. Wyley Sessions, April 26, 1937, London, England, Sessions Collection, Box 3, Folder 3, BYU Special Collections.

[84] Mission Home Agenda, Sessions Collection, Box 3, Folder 6, BYU Special Collections.

[85] Sessions 1965 oral history, 14.

[86] “Mission Home Head Released,” Deseret News, July 16, 1938.

[87] Logan Institute Circular, 1938–39, Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 9, BYU Special Collections.

[88] Sessions 1972 oral history, 11.

[89] Sessions 1965 oral history, 17.

[90] Sidney B. Sperry to Joseph F. Merrill, May 2, 1939, Provo, Utah, Sidney B. Sperry Collection, UA 618, Box 1, Folder 4, BYU Special Collections.

[91] Sidney B. Sperry to John A. Widtsoe, Sept. 2, 1939, Provo, Utah, Sperry Collection, Box 1, Folder 4.

[92] Richard O. Cowan, Teaching the Word: Religious Education at Brigham Young University (Religious Education: Provo, UT, 1998), 5–7.

[93] Boyd K. Packer offers a prophetic perspective on the struggles to develop a successful model for the Religion Department in his address, “Seek Learning, Even by Study and Also by Faith,” “That All May Be Edified” (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1982).

[94] Boyd K. Packer, “That All May Be Edified,” 43–44.

[95] See Scott C. Esplin, “Charting the Course: President Clark’s Charge to Religious Educators,” Religious Educator no. 1 (2006): 103–119.

[96] Brigham Young University: The First Hundred Years, ed. Ernest L. Wilkinson (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), 2:290–91.

[97] Sessions 1972 oral history, 11.

[98] Sidney B. Sperry to Daryl Chase, December 6, 1939, Provo, Utah, Sperry Collection, Box 1, Folder 4, BYU Special Collections.

[99] Brigham Young University: The First Hundred Years, 2:294.

[100] Cowan, Teaching the Word, 7.

[101] Sessions 1972 oral history, 11.

[102] Sessions 1965 oral history, 16.

[103] Sessions 1965 oral history, 15.

[104] Cowan, Teaching the Word, 11.

[105] “Questions and Answers on Harris’ Administration,” J. Wyley Sessions to James R. Clark, February 15, 1974, North Hollywood, California, Sessions Collection, UA 156, Box 3, Folder 3, BYU Special Collections.

[106] “Suggestions for Providing Spiritual and Religious Activities for Out-of-Town Students of the Brigham Young University,” Sessions Collection, UA 156, Box 3, Folder 7, BYU Special Collections.

[107] Cowan, Teaching the Word, 12; “Questions and Answers on Harris’ Administration,” Sessions Papers, UA 156, Box 3, Folder 3 BYU Special Collections.

[108] J. Wyley Sessions to Howard S. McDonald, July 3, 1947, Provo, Utah, Sessions Collection, Box 3, Folder 7, BYU Special Collections; J. Wyley Sessions to James R. Clark, February 15, 1974, Sessions Papers, UA 156, Box 3, Folder 7, BYU Special Collections.

[109] “Questions and Answers on Harris’ Administration” Sessions Collection, UA156, Box 3, Folder 3, BYU Special Collections.

[110] Sessions 1965 oral history, 17.

[111] Sessions 1972 oral history, 12.

[112] Sessions 1965 oral history, 18.

[113] Joseph F. Merrill to J. Wyley Sessions, Nov. 29, 1949, Salt Lake City, Sessions Collection, Box 3, Folder 7, BYU Special Collections.

[114] Sessions 1965 interview, 18.

[115] Information accessed from http://

[116] J. Wyley Sessions to Ward H. Magleby, December 29, 1967, Laguna Hills, California, Sessions Collection, Box 2, Folder 5, BYU Special Collections.