Now That You’ve Planned for the Contingencies, Plan for the Inevitable

M. Steven Andersen

M. Steven Andersen, “Now That You’ve Planned for the Contingencies, Plan for the Inevitable,” Religious Educator 10, no. 1 (2009): 113–121.

M. Steven Andersen (msandersen@amhplaw.com) was an attorney with a practice in San Diego, California when this was written.

Death is part of Heavenly Father's plan of happiness. We may actually spend more time, money, and effort preparing for unlikely contingencies than for the certainty of death.

Death is part of Heavenly Father's plan of happiness. We may actually spend more time, money, and effort preparing for unlikely contingencies than for the certainty of death.

Death is part of Heavenly Father’s plan of happiness, for “it was appointed unto man to die” (Alma 42:6). From a Latter-day Saint perspective, however, death is not the end. The scriptures assure us that those who die in the Lord “shall not taste of death, for it shall be sweet unto them” (D&C 42:46). The Lord says of the righteous that “those that die shall rest from all their labors, and their works shall follow them; and they shall receive a crown in the mansions of my Father, which I have prepared for them” (D&C 59:2) So while it is true that when we have lived together in love we appropriately “weep for the loss of them that die” (D&C 42:45), we need not fear death if we live right. One way of diminishing fear of anything, including death, is to prepare for “if ye are prepared ye shall not fear” (D&C 38:30). However, even though death itself is not to be feared, preparing for death—at least in these times—is complicated, much more so than in the days of the pioneers.

It occurs to me that as Latter-day Saints, we may actually spend more time, money, and effort preparing more for unlikely contingencies than for the certainty of death. We buy health insurance because we might get sick. We buy car insurance because we might have an accident. We store a year’s supply of food because we might go hungry. We invest for the future because we might live to be a hundred. None of this is wrong, and indeed all of it has been specifically encouraged from the pulpit. Surely, however, it is just as important, arguably more important, to plan for an event that is not a contingency. Any planning in advance will benefit both you and those you leave behind.

Despite this, there is little evidence that planning for death receives regular and consistent encouragement in our meetings and literature. We are good about preparing our children for baptism, preparing our young men for missions and the Melchizedek Priesthood, and preparing others to attend the temple. Much less attention is given to preparing our affairs in advance of our death. This is unfortunate, because modern society has become increasingly complex, and advanced preparation is not just a matter of procrastination. Often we simply do not know what to do, what papers to keep, where to put them, and so forth.

The reasons for avoiding the topic of preparing for death are not hard to fathom. Notwithstanding the certainty of death, we live in a place and time that clings to youth, considers aging a horror, and avoids contact with the dying.

My father passed away on November 29, 2005. He was eighty-seven, had been ill for ten years, and had been under hospice care for several months. In short, his death was not a surprise, and we felt ready for it, emotionally and spiritually. What was a surprise, at least to me, was how technically unprepared I felt when he was gone, notwithstanding ample warning and plenty of time to put things in order. Suddenly, my siblings and I were scrambling to accomplish things that certainly could—and definitely should—have been attended to long before.

Spurred by the loss of my father and the things we learned in that process, I started putting together a plan so that when my time comes, my loved ones will have a road map to follow and will find that much of the difficult technical aspects of death in the complex modern world have been handled. This article summarizes the results of that effort.

I expect you know some of the things you need to plan before you die, but you have not thought of everything; despite having spent scores of hours on this project, neither have I. But after working on it for a while and sharing ideas with others, I think I have made what I feel is a thorough and adequate preparation for my death. This article tells you what I have prepared.

There are several things this article does not attempt to address. First, I am not a specialist in estate planning or taxation, so I do not address those issues here. Information about guardians or conservators in the event of disability before death will not be found here. End of life issues—such as organ donation or the extent to which heroic measure should or should not be taken in the face of fatal disease or trauma—issues of organ donation, are not discussed. I offer no suggestions for those who may not wish to share all their financial information with all members of their family. I mention but make no attempt to give even a thumbnail description of such instruments as powers of attorney, durable or otherwise. I do not discuss the best way to dispose of heirloom items, though this can be a very delicate and important matter.

Paperwork: Safe, Accessible, and Up-to-Date

Just about everything you need to do to prepare for death will create paperwork. These time-of-death materials need to be managed so as to (1) keep them safe, (2) make them accessible to those who will have to deal with the aftermath of your death, and (3) keep them current.

Safe

As you will see below, the information that will be included in the paperwork you are going to generate and gather would allow an identity thief to have a field day. It must be kept secure. I suggest the purchase of a fireproof, waterproof, tamperproof safe, one that can be bolted to the floor of a closet. I also suggest the use of a bank safe deposit box, which will contain a copy of what you will put in the safe at home. This way, you and those who follow will have access to the materials in the safe even if the house burns down.

Accessible

Making the material accessible is equally important. This has two parts. First, and most obviously, if you die and no one knows how to get into your safe and bank safe deposit box, you have not solved anything. Tell your spouse and mature children where the safe is and how to open it. Give someone responsible a copy of the key and combination to both the safe and safe deposit box, and put that person’s name on the approved list at the bank. Second, make sure the materials are user friendly. Below I will make some specific suggestions in this regard, but the big-picture objective is to leave things in such a way your survivors can sit down with the materials you have prepared and be led quickly and efficiently through them. I believe you will soon discover in going through this exercise that you have not only organized things for the benefit of your survivors when you die, but have also made a pretty easy situation for anyone who must care for you if you are disabled. For that matter, you have also made easier the day-to-day management of your own affairs.

Up-to-date

Finally, bear in mind that things change quickly, and arrangements that make sense today may not be satisfactory a year from now. Keep the time-of-death materials current and up-to-date by scheduling an annual review near the date of your birthday.

Preparing for Death and Organizing Time-of-Death Materials

You are going to need to purchase a large capacity, sturdy three-ring notebook and about twenty-five tabbed dividers. The home safe needs to be big enough to hold it, and a copy of its contents will go in the bank safe deposit box. A list of the basic set of tabs might be labeled as follows below, but you will probably want to add others.

Tab 1: “When we die.” This is the first place your survivors will turn when they discover you have died. It will contain a short instructions and an overview of all else that the notebook contains. The instructions and materials behind this tab are the most complicated to assemble and will take the longest to describe in this article. The instructions in my notebook are set forth in numbered paragraphs subtitled as follows:

- Death and burial expenses. Early in the process, I want to head off any panic about what has been arranged and prepaid, and what still needs to be taken care of. In this paragraph, I tell my survivors in general terms what arrangements we have made concerning the payment of a cemetery plot, mortuary services, and a grave marker. I also tell them where in the notebook they can turn to find originals of the cemetery deed, the mortuary services contract (or insurance policy), and the grave marker.

- Handling of the Deceased. Leaving nothing to chance, I want my survivors to know whom to call in the immediate aftermath of my passing. If you have made advance arrangements with a mortuary, provide the name and phone number. We also state here our preferences for who should help dress our bodies. I recommend, where appropriate, the advance preparation of ceremonial temple clothing for burial, and your instructions should indicate where these may be found.

- Death certificates. We were amazed at how many copies of the death certificate are required. Some need to be certified copies, others can be ordinary photocopies. In this paragraph, I explain how many of each to request from the mortuary (five certified copies minimum, ten might be safer, but there is a cost).

- Cemetery arrangements. Here I provide a succinct summary of the location of the burial plots we have purchased, who to call to have the graves opened and how much this is likely to cost, and (again) where to turn in the notebook for the original documents and more detailed instructions.

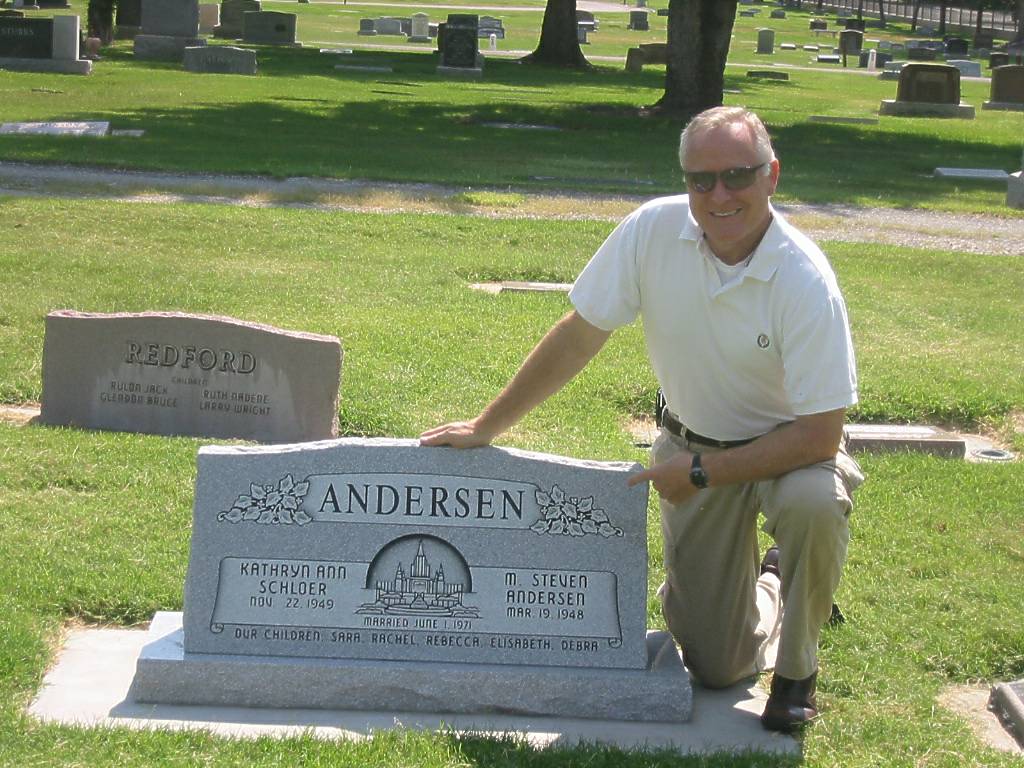

- Grave marker. After your death, your survivors may tend to think that if they do not spend lavishly, people will conclude they did not love you. My wife and I have already purchased our markers and even had them installed on our still empty burial plots. After our deaths, the stonemason will enter the death dates. This allowed us to select the style, cost, and so forth.

- Graveside service. The text here explains what we want done, for example, who should preside, and who we would like to have dedicate our graves, offer a prayer, and lead the singing. In our case, we request that the graveside service and burial precede the memorial service (seems to get the heavy lifting over with first so the memorial service can be a little lighter in spirit).

- Memorial (or funeral) service. I explain here that Kate and I have prepurchased our caskets and that each of us has sketched out the program for our memorial services. We have placed a sample printed program at the back of this first section, along with an electronic copy on a CD in a plastic sleeve so they can easily make any needed modifications, then print a final and go get it copied somewhere. This is an area where you can spare your survivors sales pitches at a time of great vulnerability.

- Obituaries. In this section we have roughed out the basic elements of our own obituaries and even decided where we want them published. Printed copies are in this same section, and are included on the same CD mentioned in paragraph 7.

- Notifications. One of the little surprises following my father’s death was how hard it was to think of all the people that should be notified without leaving anyone out and how time consuming it was to locate phone numbers and addresses. In this paragraph we include our thoughts on the subject, listing by name and phone number people to notify in the categories of official or business (including of the names and contact information for your attorney and accountant), Church, family, and friends. For good measure, we have thrown in copies of our family rosters.

- Birth and marriage certificates. We discovered that for some insurance-related purposes, you have to provide copies of birth and marriage certificates. It took some real time to find what was on hand at home and even more time to order what was not available from county registrars around the country. We have obtained these and put the originals or certified copies in plastic sleeves in the notebook in this first tab.

- Financial and legal matters. This subparagraph gives a very brief overview of our financial and legal affairs (for example, it explains that we have wills and a trust, the basic notion of how the trust is supposed to work, and identifies the basic categories of assets we own). It is merely introductory, and explains that the details are found elsewhere in the notebook.

- Use of the notebook. In this final paragraph, I list each tab that follows this first “When we die” tab and what is contained in it. It is essentially a table of contents to the rest of the notebook. It will be much easier—and shorter—to describe the remaining tabs.

Tab 2: Farewell letter. Given that the first tab has been so businesslike, we hasten to tab 2, a letter addressed to our children and grandchildren in which we express all the things we hope we do not die without being able to say in person.

Tab 3: Health insurance. If I am comatose, I want someone to know how to navigate this important aspect of my planning. Behind this tab is the original of my health insurance policy, a copy of my insurance card, and some basic instructions about how it is supposed to work.

Tab 4: Life insurance. This tab contains the originals of our life insurance policies. Ahead of these is a one page summary of what policies we have and information about how to make a claim (including phone numbers and addresses).

Tab 5: Auto insurance. It is important to let your survivors know who handles your auto insurance. This tab has the original policy. This is also helpful if you are incapacitated and loved ones are driving your car to take you the doctor and pick up prescriptions.

Tab 6: Home insurance. This contains the original home insurance policy.

Tab 7: Disability insurance. This contains the original of my disability policy. When I die, it becomes valueless, but it is essential to anyone struggling to care for me if I am in a state of incapacity.

Tab 8: Other insurance. We have what we call an “umbrella policy,” and the original is in our notebook. Put the originals of any other policies you might have in your notebook.

Tab 9: Assets and liabilities. This tab contains, first, a summary of our major assets, both investment and noninvestment, down to the level of our cars. Following that are original deeds to real estate (and accompanying title insurance policies), original certificates of title to our cars, and reasonably recent account statements from our bank.

Tab 10: Social Security. The Social Security Administration sends you a statement once in a while about what you are entitled to upon retirement. Put the current one behind this tab in the notebook. It also contains information about death and disability benefits that could come in handy.

Tab 11: Budget. Everyone should have a budget. This is for our current benefit, not for the mop up crew, but the notebook seems like a good place to put it, and it would certainly come in handy if someone had to step in and run things because you have become vegetative.

Tab 12: Pension/

Tab 12: Other investments. If you have investments other than those in tax-qualified accounts, include information about them in this tab and add copies of current account statements if applicable.

Tab 13: Bank account. The assets and liabilities tab already includes a copy of a recent account statement from your bank, but if you’re feeling charitable, put another copy here.

Tab 14: Retirement plan. The term retirement plan means different things to different people. To an estate planning attorney, such a plan may include provisions for the support of your surviving spouse, and perhaps your children and grandchildren. But as used here, it simply means a written plan for how much you can afford to withdraw each year from your investments to pay for retirement. This is helpful if you’re incapacitated. If you are organized enough to have one (and if you don’t have such a plan, you’ll want to get one), this is the place to put it.

Tab 15: Wills and trusts. You don’t need me to tell you that you should have wills and perhaps a trust. Put the originals behind this tab.

Tab 16: Powers of attorney. In addition to wills and trust, there are some other important legal documents you should consider: a general power of attorney, a power of attorney for health care, and a directive to physicians and providers of medical services (“living will”). It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss what these do for you, but their names give you an idea. Put the originals behind this tab.

Tab 17: Wallet contents. Make a photocopy of the front and back of every card you carry in your wallet or purse, including credit cards, driver’s license, health insurance card, ATM debit card, etc. If you ever lose your wallet, or if your survivors can’t find it, here is the place to turn. It will show all the numbers to call to report lost or stolen cards, or to cancel them in the event of death.

Tab 18: Home safe. You will have shared this information orally, but put information about how to access the safe in this tab. Since the notebook will be in the safe, you might wonder why I say this. Answer: if the house has burned down and the crew is resorting to the bank safe deposit box, they will be able to get a copy of the notebook and be reminded of how to access the safe, which will almost certainly contain important and valuable things beyond the notebook.

Tab 19: Safe deposit box. In this tab, remind survivors of the location of, and how to gain access to, the bank safe deposit box. You might have important stuff in there that you will want them to get, whether you are dead or incapacitated. Check with the bank to determine whether local laws place restrictions on postmortem access to safe deposit boxes.

Tab 20: Cemetery. Put the originals of your cemetery deeds behind this tab. It wouldn’t hurt to include a map of how to find the plots within the cemetery (the cemetery will provide one).

Tab 21: Mortuary. This is where you put the originals of your contracts with the mortuary (sometimes in the form of a specialized insurance policy).

Tab 22: Household bills. Someone is going to have to make decisions about the house. Make a list of all the bills you pay, list the account numbers, and tell how you generally pay them (for example, automatic debit to the bank account, automatic charge to the credit card, check, and so on).

Tab 23: Computer user names and passwords. Make a list of all the user names and passwords for online accounts you regularly use. When you are dead, it might be helpful for someone to go into these accounts to give notification, cancel subscriptions, and so forth.

Conclusion

Implementing the suggestions made in this article is not difficult, but it is time-consuming and requires some perseverance. Typically, you will begin with a rush of enthusiasm only to find it hard to stay with it until the notebook is finished. I encourage you to persevere.

At a recent family gathering, Kate and I sat down with all our children (all are adults) and got out the notebook. We explained what it was, what it contained, and turned through the various tabs to show them its contents and how to use it. There was some predictable protest from those who did not want to contemplate our demise, but it was easily overcome. We were able to give them a preview of what to do when we die and how we have made things easier for them to manage from a technical standpoint. I think they appreciated it then, but I know they will appreciate it much more later on. We have tried to teach them that we are not afraid of death, that discussion of it need not be avoided, and that when planned for, it can even be treated with a certain lightness of heart. We want to make our deaths as much a turnkey experience as possible so our children can focus without nervous distraction on the much more joyful aspects of this essential—and universal—part of God’s plan for His children.