Grim Lessons from a Torrent of Flames in California

Alexander B. Morrison

Elder Alexander B. Morrison, “Grim Lessons from a Torrent of Flames in California,” Religious Educator 10, no. 1 (2009): 149–158.

Elder Alexander B. Morrison is an emeritus Seventy.

God’s modern-day prophets repeatedly have warned us about the perilous and tumultuous times in which we live (see, for example, D&C 1). Those perils and tumults certainly include both so-called “natural” disasters of various sorts and those caused by human error or wickedness. But a new factor—global climate change—recently has emerged as a significant issue. Scientists tell us that our earth is getting warmer, for reasons which are perhaps still not fully explained. As part of that trend, more severe weather phenomena can be expected and, some believe, are in fact already occurring. Severe widespread droughts, floods, wildfires, excessively high ambient temperatures, high levels of devastating tornadic activities, an anticipated busy hurricane season in 2008, and other climate extremes plague us here in America. A recent devastating earthquake in China and a horrendous hurricane in Myanmar remind us that other nations and peoples are also suffering on a grand scale.

The pain, sorrow, and profound sense of loss experienced by so many worldwide serve as somber reminders of the ineluctable fact that mortality is intrinsically unpredictable, with periods of relative tranquility punctuated by spikes of violent disorder. We cannot ensure or even assume our temporal safety but must look elsewhere for the inner peace—that “lovely child of heaven”[1]—sought by all who love the Lord and desire to dwell with Him.

At least some of the pains we suffer and trials we experience come as an inevitable consequence of life itself. We live in a world governed by natural laws, not all of which operate for our short-term benefit. Thus, we have no immunity against a host of diseases and cannot escape the accidents and misfortunes that are inherent in our own biology or are related to the physical world in which we live. If wildfires devastate our neighborhood and our home is set ablaze, we may lose not only property but also life itself. If we live in the low-lying lands of the Ganges Delta, and a devastating hurricane and storm surge overwhelm our dwelling place, personal and community-wide disaster may occur. As we grow older, all of us suffer the natural results of aging. We may delay death from disease or accidents, but ultimately we cannot avoid it. It is all part of the natural order of things and one of the conditions we agreed to when we came to earth.

Some may query why God permits disasters to occur. Why doesn’t He, out of the abundance of His omniscient power, simply stop them and permit us all, in whatever land we live, to wear out our lives in tranquility, peace, and security? Why is there so much suffering, so many tears, so much sorrow?

I do not believe that any of us knows the precise, detailed answers to those and many other important questions relating to human suffering, but we do know the grand outlines of the purposes of life. The Father’s great plan of happiness, known also by other terms including the plan of salvation (see Alma 42:5), teaches us that mankind chose to enter mortality and that we came to earth with full understanding that to do so would inevitably require us to undergo adversity. President Spencer W. Kimball wrote:

We knew before we were born that we were coming to the earth for bodies and experience and that we would have joys and sorrows, ease and pain, comforts and hardships, health and sickness, successes and disappointments. We knew also that after a period of life we would die. We accepted all these eventualities with a glad heart, eager to accept both the favorable and the unfavorable. We eagerly accepted the chance to come earthward even though it might be only for a day or a year. Perhaps we were not so much concerned whether we would die of disease, of accident, or of senility. We were willing to take life as it came and as we might organize and control it, and this without murmur, complaint, or unreasonable demands.[2]

It hardly needs repeating that the adversity found in mortal life is closely related to moral agency. Anything which removed adversity from our lives, with its concomitant suffering, disappointment, and tears, would inevitably render null and void the Father’s great plan of happiness for His children. Moral agency, a vital component thereof, would no longer exist.

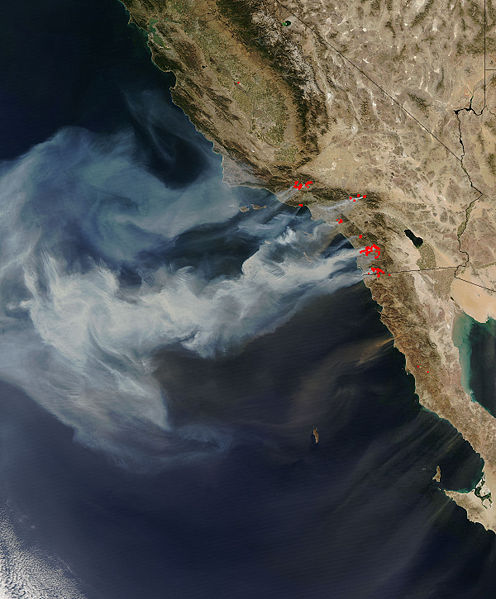

NASA satellites capture remarkable images of the wildfires in Southern California. NASA/

NASA satellites capture remarkable images of the wildfires in Southern California. NASA/

Much of the perceived meaning of adversity depends on our perspective. Some, faced with the grim realities of unpredictable turmoil and violent loss, overwhelmed by pain and tears, grow bitter and give up in despair. In their bitterness, they may rail at God and the seeming injustice of life. Others use the experience, troubling as it is, to learn there must needs be “an opposition in all things” (2 Nephi 2:11). They realize that our adversity and afflictions “shall be but a small moment” in our eternal journey (D&C 121:7). They come to understand, as did the Prophet Joseph Smith, that “all these things shall give thee experience, and shall be for thy good” (D&C 122:7). And they comprehend that no mortal suffering, regardless of how painful, even begins to equate with that of the Savior, who came to earth “to suffer, bleed, and die” for man.[3] He who “hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows” (Isaiah 53:4) endured “temptations, and pain of body, hunger, thirst, and fatigue, even more than man can suffer” (Mosiah 3:7). True disciples are able to see personal trials in a broader perspective, in their true light—as opportunities to grow spiritually and, in the long term at least, as blessings which refine and purify receptive souls.

Trials and tribulations thus are essential for our spiritual growth. Joseph Smith, who certainly endured more than his share of life’s problems, understood that principle. Said he, speaking to the Twelve on one occasion: “You will have all kinds of trials to pass through. And it is quite as necessary for you to be tried as it was for Abraham and other men of God, and God will feel after you, and He will take hold of you and wrench your very heart strings, and if you cannot stand it you will not be fit for an inheritance in the Celestial Kingdom of God.”[4]

“That’s all very well,” you may say, “but the Twelve are stronger and more spiritually strengthened and mature than I am. Surely what applies to them isn’t meant for me.” I don’t agree—all who are or may be called Saints are held to the same standard of conduct. Each of us individually, regardless of our position in the Church or the world, is expected to show our worthiness by our behavior. “He that hath my commandments, and keepeth them, he it is that loveth me,” Jesus said (John 14:21).

True disciples realize that Elder Orson F. Whitney spoke an eloquent truth when he said: “No pain that we suffer, no trial that we experience is wasted. It ministers to our education, to the development of such qualities as patience, faith, fortitude and humility. All that we suffer and all that we endure, especially when we endure it patiently, builds up our characters, purifies our hearts, expands our souls, and makes us more tender and charitable, more worthy to be called the children of God . . . and it is through sorrow and suffering, toil and tribulation, that we gain the education that we come here to acquire.”[5] (Incidentally, Elder Quentin L. Cook, then the newest member of the Quorum of the Twelve, drew upon the essence of Elder Whitney’s remarks in commiserating with members of the Poway California Stake on October 27, 2007.)[6]

Secure in their knowledge that God’s love for them never varies (and indeed cannot vary—His very nature forbids it), the hearts of those who see adversity as a teacher, and not a snare which entangles them, resonate with the Apostle Paul’s glorious declaration: “For I am persuaded, that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, Nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Romans 8:38–39). With that understanding, they soldier on, enduring with faith and patience “all things which the Lord seeth fit to inflict upon [them]” (Mosiah 3:19). They stand steady as an example to others, recognizing that shared burdens somehow are made lighter and that courage is infectious.

During October 2007 a series of sixteen devastating wildfires swept through Southern California, from north of Los Angeles to southern San Diego County. More than 1,900 homes were destroyed, and many others damaged, as the fires raged over scores of thousands of acres. At least seven deaths resulted. Property damage was in the billions of dollars, and half a million people were evacuated from their homes, some for several weeks.

There are, I believe, important lessons to be learned from the California fires and from other disasters at home and abroad. They are lessons which apply to all of us, both those directly affected, and others like myself who witnessed, wept, and worried from afar. Unless these lessons are learned and applied wisely, the sheer horror of the pain and sorrow felt by so many may blight and destroy lives. But that need not be if we but learn to “trust in the Lord with all [our] heart; and lean not unto [our] own understanding” (Proverbs 3:5). I believe these lessons supplement but do not replace those mentioned previously in relation to the Trolley Square shootings in Salt Lake City earlier in 2007.[7]

In focusing on the California fires, I do not wish in any way to suggest that the suffering and loss felt there was greater than—or perhaps even equal to—those suffered by people elsewhere around the nation and globe. I focus on the fires in California only to illustrate generic lessons to be learned by all of God’s children when faced with the inevitable tears and sorrow which come, in one way or another, to all of humankind.

Disasters Can Enhance the Sense of Community

Survivors of tragedies typically suffer from a profound sense of loss, which may last for a long time. The fundamental assumptions on which survivors’ perceptions of reality are based are overturned, or at least severely shaken, and they experience a major disturbance in their sense of inner peace and tranquility. In physiological terms, their inner homeostasis is disrupted, and they must seek a new equilibrium. In the process of attaining this, they may need to discard some perceptions of what matters in their lives, adjust others, and accept some that are new to them.

That new equilibrium, with its necessary adjustment of values and mores, is made easier to attain as sufferers enhance their sense of fellowship with others. In the fellowship of suffering many find a sense of community never before experienced. The British discovered that fundamental truth during the Blitz of World War II. Of these perilous times, as Britain reeled under German air attacks by night, Winston Churchill wrote: “These were the times when the English, and particularly the Londoners, who had the place of honour, were seen at their best. Grim and gay, dogged and serviceable, with the confidence of an unconquered people in their bones, they adapted themselves to this strange new life, with all its terrors, with all its jolts and jars.”[8] Churchill recalls a particularly difficult night, with heavy bombing in central London, when one Londoner he greeted noted, with grim gaiety, “It’s a grand life, if we don’t weaken.”[9] In that sense of “we’re all in this together” there is great strength, both for the individual and for the community as a whole.

As we discover that we’re all in this together, we are led to a great truth: all men and women everywhere are our brothers and sisters. As we join in the fellowship of suffering, we find that we are tied inextricably to everyone else, and they to us, by the bonds of kinship. When they bleed, we hurt; when they weep, we mourn. Their pains and sorrows become ours. And we come to realize that only to the extent we are willing to “bear one another’s burdens . . . and . . . mourn with those that mourn . . . and comfort those that stand in need of comfort” (Mosiah 18:8–9) can we ever become a Zion people, reconciled to God. To Cain’s cynical and dismissive question, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” (Genesis 4:9) we reply, “No, but I am his brother, and thus I share in his sorrows and must do all I can to alleviate them and bind up his wounds.”

The enhanced sense of community in the face of suffering was experienced by many Latter-day Saints in Southern California, often through selfless service to others. Many were overwhelmed by the kindness of their fellow Church members, friends, and neighbors. Religious, socioeconomic, and ethnic differences were forgotten as all joined to provide service for each other. It was a time when many undoubtedly remembered with renewed understanding Paul’s words to the Athenians: “[God] hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth” (Acts 17:26).

One Church member in California who delivered “sifter boxes” to destroyed homes ran into owners who initially were wary of him being around their properties. As always occurs in every disaster, there were some miscreants in California who took advantage of others’ misfortune to enrich themselves. But when the property owners found the Church member was only there to help, their attitudes softened and our member was able to have comforting conversations with them. One shared the sorrow his family felt over having their dog die in the fire which destroyed their home.[10] Often what people needed most was a loving word of encouragement, a hand of fellowship, a sincere assurance that others cared about them and stood ready to help.

Societies in Developed Countries Are Increasingly Vulnerable to Disasters

At first glance, this statement may seem not to apply to the United States of America, the most powerful country in world history. But the truth is that as our society and those in other developed countries have grown more sophisticated and specialized, our vulnerability to disasters actually has increased. We now have little surge capacity in our health care, food distribution, and communications systems. Our energy sources (principally natural gas, coal, oil, and electricity) may come from hundreds, even thousands of miles away and are not under individual, community, or even state control. In the simpler days of our grandfathers, most of our food and energy sources were produced locally, and people were, in general, much more self-reliant than at present. Our society is characterized by interdependence between components: if one fails, there may be a cascade of interrelated failures.

The interactions between the various components of our increasingly complex societies can have unforeseen effects. Many experts believe, for example, that the California firestorm did not result simply from someone carelessly playing with matches, although at least two of the sixteen fires apparently were caused by arson. But the confluence of Santa Ana winds blowing at high velocity from inland deserts over a drought-stricken land, an overabundance of debris on the forest floor, and the intrinsic problems of protecting suburbs that push deeper into flammable wild lands each year, helps explain the cause of most of the California fires.[11]

Prudent Planning Precedes Proper Performance

If there is one lesson to be learned from the California fires of 2007, it is the need to plan ahead. Admittedly, the perfect storm will defeat the perfect plan every time. We must therefore be flexible and prepared to improvise and adjust as necessary. To do so requires intellectual and judgmental flexibility more than unlimited resources. Furthermore, as every good military person knows, the best plan requires adjustment as soon as the first shot is fired.

That said, however, there simply is no substitute for prudent planning and the practice that goes with it if we are to respond properly to whatever crisis may come our way. A word of caution: though no planning exercise can be considered foolproof, it is both wise and prudent to plan for the worst case, not the best. It is essential to know at the individual and family levels what to take with you if you have to leave your home at short notice. Highest priority must go to getting the people involved safely away, with special attention to vulnerable sub-groups, including the old, the poor, children, and the infirm. But proper consideration must also be given to pets and other domestic animals, cash, valuable documents, vital genealogical information, and so forth.

There simply is no one-size-fits-all plan: each person, family, community, and business organization must prepare differently, taking into account the likely nature of what may have to be faced. One Church member in California emphasized the need for prudent planning. Said she, “We learned something from this—be organized. Know where everything is. Have a checklist.”[12] She and her family were shocked to see flames approaching and had trouble thinking about what they wanted to save in their limited time with limited space.

It goes without saying that individuals and families must not only plan but also practice carrying out the plan they produce. Every time a plan is practiced, flaws, errors, and shortcomings are exposed and illuminated and changes for the better can be made.

The first seventy-two hours after an emergency are likely to be the most critical. Planning, preparation, and practice will pay big dividends during this vital period. The most effective preparations for and response to disasters of any sort are found in the principles of self-reliance at personal and family levels.

When Michael Leavitt, the federal secretary of Health and Human Services, came to Utah in April 2006 to discuss preparations for a possible influenza pandemic, his central message was “do not depend totally on government(s) to bail you out of trouble. We will want to help, of course, but in the short-run at least, local resources will determine the outcome.” [source/ footnote?] Granted, Mr. Leavitt was not talking about catastrophic fires, but his basic message, which calls for self-reliance, rather than total dependence on government, seems applicable in a generic sense.

Latter-day Saints have been advised by the living prophets for more than seventy years to store food, water, clothing, and other essentials for a day of need. Sadly, I think that too few of us have listened and acted as we know we should. I recognize that the California wildfires were capricious, sparing one house while destroying others around it. But the wisdom of listening to and acting on the advice of the prophets cannot be questioned. We have, after all, the sure and certain promise that the Lord is bound if we do what He says, but if we do not do what He tells us to do, we have no promise (see D&C 82:10).

“If Ye Are Prepared Ye Shall Not Fear”

Doctrine and Covenants 38:30 sums it all up. We are to prepare, as best we can, for whatever eventualities lie in the future, be they good or bad. Then, and only then, after we have done our best, are we promised freedom from fear. I testify that faith will trump fear every time, as hopelessness and despair give way to gratitude for blessings received and promised, and growing confidence in God’s love for us. Now, of course, the Lord sends the rain on the just and on the unjust (see Matthew 5:45), so we have no promise of a life free of adversity. Far from it: the scriptures remind us that “whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth” (Hebrews 12:6). But what is really important to remember in any discussion of adversity has already been pointed out. Adversity’s presence in our lives is essential if we are to grow spiritually. If life is the anvil, adversity is the hammer that shapes and molds us into something better, more suitable for the Lord’s purposes, than we otherwise would be.

Preparation involves both temporal and spiritual elements. When Jesus said “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect” (Matthew 5:48), He meant what He said. To do so will, of course, take the eternities to accomplish. It is not a task to be completed in mortality. The Prophet Joseph Smith, who understood that principle, summarized it as follows: “When you climb up a ladder, you must begin at the bottom, and ascend step-by-step, until you arrive at the top; and so it is with the principles of the gospel—you must begin with the first, and go on until you learn all the principles of exaltation. But it will be a great while after you have passed through the veil before you will have learned them. It is not all to be comprehended in this world.”[13]

In summary, the terrible wildfires which swept as a torrent of flame over much of Southern California in October 2007 resulted in widespread destruction and untold suffering and sorrow. But their effects and those of other disasters, both natural and man-made, can also provide valuable lessons for the future as we adopt an eternal perspective on life and accept the vital role of adversity in helping us to grow spiritually. Essential parts of the necessary healing process include enhancement of our sense of community, a recognition that our sophisticated and complex society is increasingly vulnerable to disasters, and the need for prudent planning to mitigate (though it can never totally eliminate) the effects of disaster on our lives. Above all else, we must recognize that faith trumps fear: “If ye are prepared ye shall not fear.”

Notes

[1] Joseph Smith, in an appeal for peace and goodwill, addressed to the people of Missouri, Nauvoo, March 8, 1844, as quoted in Larry E. Dahl and Donald Q. Cannon, eds., Encyclopedia of Joseph Smith’s Teachings (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1997), 468.

[2] Spencer W. Kimball, Tragedy or Destiny? (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1977), 12.

[3] “How Great the Wisdom and the Love,” Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 195.

[4] Encyclopedia of Joseph Smith’s Teachings, 681, address by John Taylor, Salt Lake City, June 1883.

[5] Orson F. Whitney, as cited in Spencer W. Kimball, Faith Precedes the Miracle (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1972), 98.

[6] Church News, November 3, 2007, 7.

[7] Alexander B. Morrison, Religious Educator 8, no. 3 (2007): 31.

[8] Winston S. Churchill, Their Finest Hour (New York: Bantam Books, 1962), 307.

[9] Churchill, Their Finest Hour, 308.

[10] Church News, November 3, 2007, 10.

[11] Newsweek, November 5, 2007, 30.

[12] Church News, November 3, 2007, 10.

[13] Encyclopedia of Joseph Smith’s Teachings, 519, King Follett Discourse, Nauvoo, April 7, 1844.