Wuppertal Branch

Roger P. Minert, “Wuppertal Branch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 371–376.

A week after the president of the West German Mission departed Frankfurt, he wrote from Copenhagen, Denmark, regarding the status of several small branches. Two of those were the Barmen and Elberfeld Branches of the incorporated city of Wuppertal. President Wood recommended that the two branches be joined into one in order to strengthen the Church’s presence in that city. [1] It is not known precisely whether that happened or when. For purposes of describing the activities of individual Saints from Wuppertal, it will be assumed that the two branches were indeed combined.

The Wupper River runs west through a narrow valley toward the Rhine. On its way it links the historic towns of Barmen on the east and Elberfeld on the west. The city of Wuppertal was formed by combining those towns and several others. Beginning in 1903, the famous Schwebebahn (suspended monorail) allowed easy travel through the city as it glided suspended above the river. By the time World War II began, 405,000 people were living in Wuppertal.

Very little is known about the Wuppertal Branch during the war, and the available eyewitness testimonies do not mention the location of the meeting rooms or leadership of the branch. It is known only that in the summer of 1939, the Elberfeld Saints were meeting in rooms in the Hinterhaus at Uellendahlerstrasse 24, and their Barmen counterparts met at Unterdörnen 105. Neither branch had a functioning Relief Society, MIA, or Primary at the time. [2] One eyewitness identified Paul Schwarz as the branch president in 1943; he had been the president of the Barmen Branch in 1939. [3]

| Wuppertal-Barmen Branch [4] | 1939 |

| Elders | 6 |

| Priests | 1 |

| Teachers | 0 |

| Deacons | 2 |

| Other Adult Males | 4 |

| Adult Females | 20 |

| Male Children | 1 |

| Female Children | 1 |

| Total | 35 |

| Wuppertal- Elberfeld Branch [5] | 1939 |

| Elders | 2 |

| Priests | 2 |

| Teachers | 3 |

| Deacons | 4 |

| Other Adult Males | 5 |

| Adult Females | 22 |

| Male Children | 3 |

| Female Children | 3 |

| Total | 4 |

Rudolf Schwarz (born 1914) was the superintendant of the Sunday School in the Barmen Branch when the war began, but he was soon in uniform (for the third time). He married Charlotte Becker in 1938 and was a father to little Helga. When it came time for his unit to swear the oath of a German soldier, his staff sergeant refused to allow him and two other soldiers to participate, insisting that they were not Catholics or Protestants. (One was of the Baptist faith.) When the commanding officer learned the next day of the mistake, the three were ordered to report to the parade ground in dress uniform, and the ceremony was repeated for their sake. According to Rudolf, “This was a very interesting beginning in the German army.” [source info for Rudolf Schwarz missing]

With his time and grade as a soldier, Rudolf was a top sergeant and adjutant by the end of 1941. By then, the German army had moved hundreds of miles into the Soviet Union and was experiencing the terrible Russian winter. On January 7, 1942, the Red Army broke through the German lines, and chaos threatened. The temperature dropped to thirty to forty degrees below zero, and the Germans were not as well dressed as their enemies. At a time when a determined commander was needed, Rudolf’s captain had a nervous breakdown and was out of commission. Rudolf stated, “I felt it was my job to take over the command.” He organized a scouting mission, learned that the enemy soldiers were only about one hundred feet away, and then positioned his men with their machine guns to repel the attack. They were successful, and Sergeant Schwarz accepted the surrender of about one hundred soldiers. Many were wounded, so he transferred them to a local village and asked the women there to care for the men. All this was done without any involvement of the captain, who afterwards was awarded the Knight’s Cross (although Rudolf claimed that everybody gave him the credit for the victory).

Fig. 1. Wuppertal-Elberfeld Branch in early 1939. (G. Blake)

Fig. 1. Wuppertal-Elberfeld Branch in early 1939. (G. Blake)

A week later, Rudolf was in combat again and assisted in the destruction of Soviet tanks, for which he was awarded the Iron Cross First Class. Soon the enemy was not the Red Army but the terrible cold. Rudolf and his men were crossing a long stretch of ice and learned an important lesson in survival:

We walked about thirteen hours. We found out that the cold makes you mentally and physically very unstable. At some time you would like to lay down and forget all about it. If we saw somebody laying down or sitting down, we kicked them and told them to go on. Two of [the men] died. It was a great march which nobody can imagine how painful it was to walk under that condition. Nothing to eat, nothing to drink. . . . Everybody had problems to walk—like you had arthritis everywhere.

By March 1942, Rudolf Schwarz was a platoon commander and was soon on his way home on leave. He first visited his parents and attended church with the Wuppertal Branch, then headed south to Bavaria, where his wife and daughter were staying in the town of Unterelsbach (Upper Franconia). From there it was back to the Eastern Front, where Rudolf stepped on a land mine on July 7, 1942: “A terrible noise, and I was thrown up into the air and I turned around in the air and fell on the ground.” His men carried him back to a field hospital, and he spent the next year in various hospitals. Surgery and orthopedic devices eventually allowed him to walk again, but he was released from active duty in 1943. While in the hospital in Deutsch Krone, Pomerania, he was visited by Lotte and Helga. His condition was worsened several times by infections and appendicitis, but he eventually recovered and was downgraded to reserve status.

Gerda Rode (born 1921) was surprised in 1942 when she received a letter from an LDS soldier of the Bad Homburg Branch, near Frankfurt. Hans Gerecht had been a missionary in Wuppertal in 1937–38 and recalled her as a “very blond girl.” It was several months before she responded to his letters. He was already a Wehrmacht soldier and as such was not free to visit her. In April 1943, he was given leave to go home to Bad Homburg and asked her to join him there. Just after they parted, she received a telegram with the text: “Do you want to be my wife? Please let me know immediately. Hans.” Her reply was one word in the affirmative.

In June 1943, Hans Gerecht was allowed to visit his fiancée in Wuppertal. He was there just in time to experience a horrific attack on the city. As they were huddled in a cellar, the building was hit; one man close to them was killed, and they ended up digging their way out of the rubble. After moving Gerda and her mother to a safe location, Hans returned to help rescue their neighbors. They soon learned of a comical situation involving a Brother Fischer from the branch. He was suffering from diarrhea and was sitting on the toilet when a bomb hit his apartment building. When the house collapsed he dropped a full story—still seated on the toilet—, but was not seriously injured.

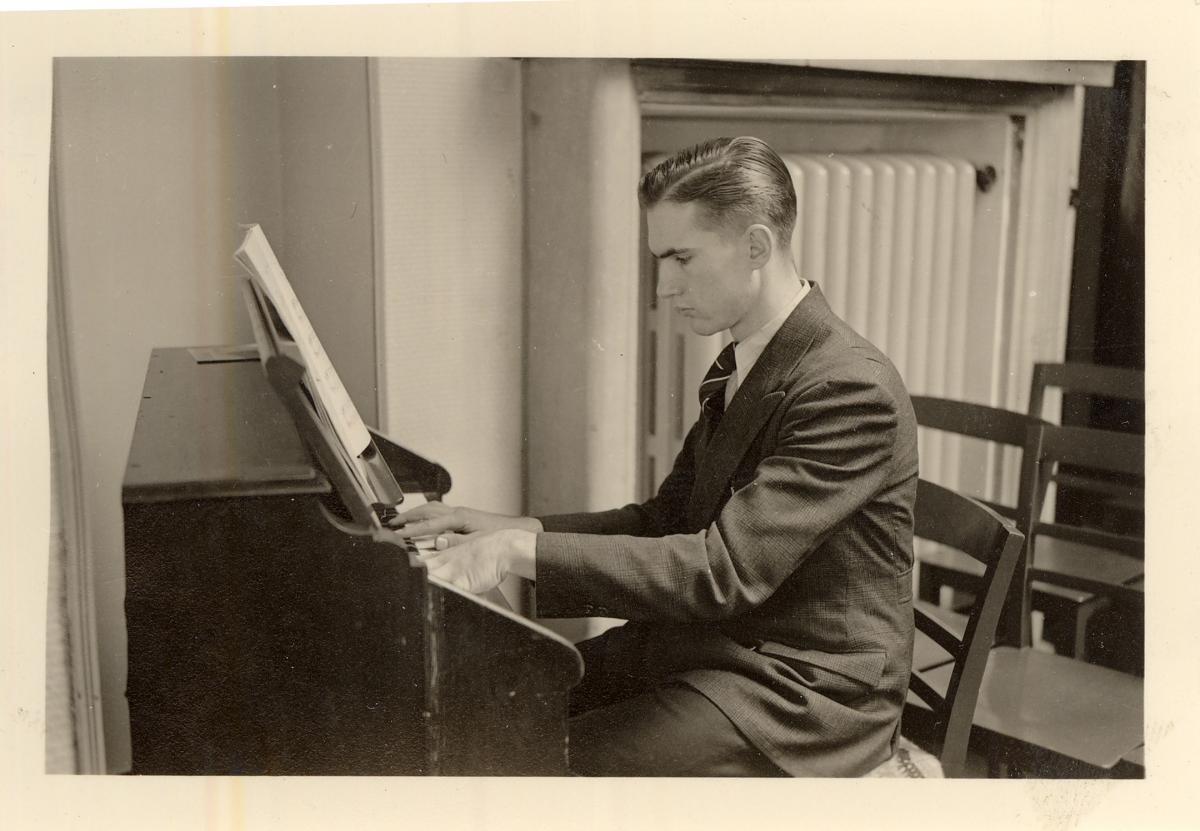

Fig. 2. Missionary George Blake at the pump organ in Wuppertal. This model of organ could be seen in meeting rooms all over Germany during the war. (G. Blake)

Fig. 2. Missionary George Blake at the pump organ in Wuppertal. This model of organ could be seen in meeting rooms all over Germany during the war. (G. Blake)

Returning to their apartment house, Gerda, her mother, and Hans gazed upward into the open apartment; the building’s façade had been blown away. They were able to go upstairs and rescue a very expensive mattress, after which they went to the Bühlers, another LDS family, and were given a place to sleep. Homeless, the three took the train to Bad Homburg. Hans was soon given another leave, and he and Gerda were married in Frankfurt on July 24, 1943. She recalled one important aspect of the event: “I had nothing to wear. A sister in Frankfurt gave me her long black dress and a white veil. This sister was so kind, she gave this dress to all the brides, and it fit them all. We were all undernourished and slim.” After a few days together as man and wife, Hans was on his way back to the Eastern Front.

The news of the terrible attack on Wuppertal was communicated throughout the West German Mission, and a relief campaign was instituted. The following report was filed in Frankfurt regarding that campaign: [6]

9 Jul 1943:

According to general newsletter no. 2 of the West German Mission dated June 27, 1943, as well as by the request of the Hamburg District Presidency, a request is being made of all members to voluntarily donate anything they can—be it money, clothing, or other items—for the relief of the members of the Ruhr District, especially the branches in Barmen and Elberfeld, who have lost their homes in recent air raids. The following items were then collected and prepared for shipment to the district leaders in Hamburg:

Brother Louis Gellermann 200 Marks

Brother Christian Tiedemann 20 Marks

Emma Hagenah 5 Marks (non-member friend)

225 Marks total

The following items were donated by Sister Helene Gellersen of Stade:

[coats, underwear, sweaters, pants, blankets, jackets, pens, paper, cutlery, soap, cups, etc.]

Stade on July 9, 1943 Louis Gellersen, branch president

Fig. 3. Sisters of the Wuppertal Branch. (G. Blake)

Fig. 3. Sisters of the Wuppertal Branch. (G. Blake)

In March 1944, Gerda Rode Gerecht’s mother passed away. Three months later, her brother Ernst was killed in the first fighting against the invading Allies near Normandy, France. Just prior to her brother’s death, she welcomed Hans home for a furlough. When it came time for him to report for duty again, he convinced her to ride the train to Vienna, Austria, with him so that they could spend more time together. He smuggled her onto a troop train; after they said good-

bye in Vienna in May 1944, she returned to Bad Homburg.

During the last year of the war, Rudolf Schwarz was sent to a technical school in Nuremberg, not far from where his family was living in Unterelsbach. His course was not yet completed when Nuremberg was devastated in the attack of January 2, 1945, but he was at least prepared to work as a draftsman. Rudolf returned to Unterelsbach and found work in the nearby town of Bad Neustadt. With the American army approaching the area in March 1945, the local Nazi Party leader approached Rudolf and informed him that he was to lead the local Volkssturm (home guard); he was the best man for the job, based on his combat experience.

My job was to get about 100 old men ready to fight in that very last war. It was a joke, but I couldn’t get out right away, so I started training and organizing in regulated time with these men which I hardly knew. . . . After a while the situation got real critical, as the front line came closer to our area. One day we could hear the artillery from the American army. I had to make a decision one way or the other what to do with that Volkssturm. . . . I [received] orders from the Party that I was in charge of the whole area. . . . Needless to say we didn’t have any weapons. So I dissolved the Volkssturm as an organization. I told the men to go home and take care of their families.

Rudolf knew that he could be shot as a traitor, but the Americans were in town within hours, and he explained to them that no defense would be offered by the local men.

One day in April 1945, Gerda went to the home of Hans’s parents. She recalled what happened there:

I had a key. I waited for them and lay on the sofa. “Gerda,” [Hans] called with a voice full of love and sadness. “Gerda,” I heard my name the second time. I looked around; I didn’t see him but felt his presence. Later I heard that this must have been the time that he was shot in the face. . . . He died at that very time. This was confirmed when I was notified . . . that he had given his life for the fatherland in heavy fighting.

One last tragedy awaited the young widow: Gerda’s father, Heinrich Jakob Rode, was shot with several other men by the Gestapo in April. She made inquiries after the war and was told that seventy-two men were rounded up as traitors—apparently having refused to fight as Volkssturm—and executed by the Gestapo. She claimed to have found the mass grave in 1948 near Immigrath, about twenty miles south of Wuppertal. During her visit, she located a neighbor who confirmed that the atrocity had indeed occurred there. A monument marked the spot, but no names were engraved thereon.

The city of Wuppertal suffered substantial losses inflicted by 126 air raids. At least 8,363 people were killed, and 38 percent of the city was destroyed (including 64 percent of the dwellings). The American army entered the city on April 16, 1945. [7]

In the summer of 1945, Rudolf Schwarz was determined to take his family (which now included a son named Roman) back to Wuppertal. His wife had acquired some nice furniture during her four years in Unterelsbach, and they wanted very much to take it back with them. Rudolf was successful in arranging with a railroad agent for the shipment of the furniture in a box car to a point close to Wuppertal. After arriving there, local friends were enlisted to transport the valuable cargo to Wuppertal, where the Schwarz family prepared for life in a new Germany.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Wuppertal Barmen and Elberfeld Branches did not survive World War II:

Catharina Emilie Callies b. Elberfeld, Wupperthal, Rheinprovinz, 7 Feb 1869; dau. of Johann Ferdinand Callies and Katharina Rau; bp. 20 Sep 1942; conf. 20 Sep 1942; m. 1 Oct 1890, Ernst Ewald Steffens; d. stroke 12 Nov 1944 (FHL microfilm 68808, no. 55; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 879; FHL microfilm 68803, no. 879; IGI)

Karl Adolf Harzen b. Elberfeld, Wuppertal, Rheinprovinz, 23 Nov 1890; son of Alexander Harzen and Auguste Druseberg; bp. 13 Nov 1932; conf. 13 Nov 1932; ord. teacher 26 Nov 1933; d. pleurisy 30 Jan 1941 (CHL CR 375 8 2430, no. 976; FHL microfilm 162777; 1935 census; IGI)

Richard Kühhirt b. Mühlhausen, Sachsen (province), 22 May 1896; son of Julius Kindhoff or Windhoff and Christine Kuhirt; bp. 27 Mar 1905; conf. 27 Mar 1905; m. 2 Jun 1915, Luise Emma Seyfarth; d. influenza and heart attack 25 Feb 1941 (FHL microfilm 68786, no. 35; FHL microfilm 271381; 1935 census; IGI)

Alwine Morenz b. Elberfeld, Wuppertal, Rheinprovinz, 17 Sep 1885; dau. of Gustav Theodor Moranz and Anna Maria Catharina Alwine Klein; bp. 15 Apr 1923; conf. 15 Apr 1923; m. Elberfeld 30 Mar 1912 to Heinrich Jakob Rode; 2 children; d. cardiac asthma, Bad Homburg, Hessen-Nassau, 24 Mar 1944. [Source(s) missing]

Mathilde L. Oswald b. Mühlhausen 27 May 1872; dau. of Ludwig Oswald and Regine ——; bp. 29 Oct 1903; conf. 29 Oct 1903; m. Fritsch; d. old age 5 Jul 1943 (FHL microfilm 68803, no. 922; FHL microfilm 25770; 1930 and 1935 censuses)

Ernst Rode b. Elberfeld, Rheinprovinz 22 Jun 1909; son of Heinrich Jakob Rode and Alwine Morenz; bp. 15 Apr 1923; conf. 15 Apr 1923; m. 14 or 16 Dec 1934, Hilde Metzer or Melzer; private first class; k. in battle France 12 Aug 1944; bur. La Cambe, France (SLCGW; FHL microfilm 68808, no. 51; FHL microfilm 68786, no. 568; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Emilie J. E. Schrick b. Vohwinkel, Rheinprovinz 18 Jan 1870; dau. of Wilhelm Schrick and Julie Hollhaus; bp. 6 Apr 1930; conf. 6 Apr 1930; m. 10 Feb 1890, Karl Amhäuser; d. asthma and old age 10 Feb 1941 (CHL CR 375 8 2430, no. 904; FHL microfilm no. 25710; 1930 census; IGI)

Heinrich Wagner b. Elberfeld, Rheinprovinz 21 Nov 1856; son of Heinrich Wagner and Wilhelmine Meissner; bp. 28 Oct 1910; conf. 28 Oct 1910; ord. deacon 6 Jul 1913; ord. priest 21 Mar 1915; d. 25 Jun 1943; bur. Elberfeld, Wuppertal (FHL Microfilm 68786, no. 580; www.volksbund.de; FHL microfilm no. 245291; 1925 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Notes

[1] M. Douglas Wood, papers, CHL MS 10817.

[2] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[3] Gerda Roda Gerecht, “My Marriage to Hans Gerecht,” CHL MS 19186.

[4] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Lübeck Branch history, 10, CHL LR 5093 21.

[7] Wuppertal city archive.