Vienna Branch

Roger P. Minert, “Vienna Branch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 459–475.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was nearly four decades old when a branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was established in the capital city of Vienna just after the turn of the century. [1] The city was the political, cultural, scientific, and industrial capital of the empire and attracted people from many lands speaking many languages. Years later it would be commonly claimed that a genuine native of Vienna must have a Hungarian grandfather and a Bohemian grandmother. Vienna was at the same time the capital of Austria, a predominately Catholic country where German was the only official language.

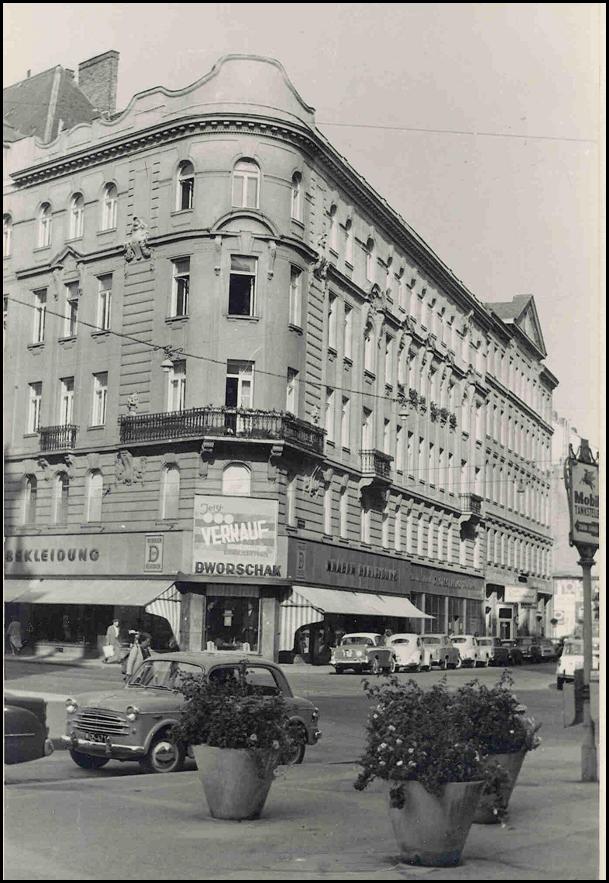

By 1938, the Vienna Branch consisted of perhaps 160 members who lived in many of the twenty-three Bezirke (districts) of the metropolis. The home of the branch was Seidengasse 30 in District VII (Neubau). The rooms were acquired in July 1935 and served their purpose well for five decades. According to branch president Alois Cziep (born 1893), the Church rented all of the rooms on the second floor as well as the rooms on the main floor to the left of the portal. Access to those rooms was a door to the left just inside the portal. [2]

Fig. 1. Seidengasse 30 in Vienna. The Church rooms were to the left of the main entry on the main and second floors. Note the sign in the first window left of the entry. (E. Cziep Collette)

Fig. 1. Seidengasse 30 in Vienna. The Church rooms were to the left of the main entry on the main and second floors. Note the sign in the first window left of the entry. (E. Cziep Collette)

Gertrude Mühlhofer (born 1915) described the rooms rented by the branch at Seidengasse 30:

We walked into the portal and on the left side was a door to our rooms. We then went up some stairs and reached the cloakroom. On the right side, there was the restroom. Then, there was a small room in which the youngest children had their classes. On the right side, there were two smaller rooms also. There was also a large room for sacrament meeting. I cannot remember that there were pictures on the wall. We had single chairs that could be connected and could not be moved easily. There were about sixty people there on a typical Sunday and there were quite a few children. [3]

Gertrude had been out of work for five years when Austria was annexed by Germany. By a stroke of luck, she was offered employment in the parliament, as she later explained:

I received very good training. I earned three hundred Marks a month and that was very good money back then. They also gave me extra money the first month so that I could buy myself something nice to wear. I had gone directly from babysitting to the new job and I looked pretty good. My task was to find all the legionnaires. I had a chauffeur who drove me everywhere to find the veterans jobs and places to live. I did this for five to six months, after which I became the secretary to the leader of the German Arbeitsfront. I stayed in Vienna and worked this job until I had my first baby [in September 1942].

Fig. 2. The main meeting room at Seidengasse 30. (E. Cziep Collette)

Fig. 2. The main meeting room at Seidengasse 30. (E. Cziep Collette)

Young Emma (Emmy) Cziep (born 1928) recalled an interesting feature of the rooms at Seidengasse 30: “One of my favorite rooms was padded—one of those old-fashioned rooms where there was leather padding on the wall with buttons in them. I guess they used to call them smoking rooms. That was the priesthood and Sunday School room.” [4] Emmy also recalled the stark contrast between those meeting rooms and the buildings in which her friends and neighbors worshipped: “We were sitting in this small apartment and down the street was a huge cathedral.”

Emmy’s father, Alois Cziep, had been called to serve as branch president in 1933 and remained in that position until after the war. In September 1938, the Cziep family moved into a nice second-story apartment at Taborstrasse 20 in District II. President Cziep was the manager of a store in the Nordsee Seafood Company chain. Having lost an eye, he was classified as unfit for military duty and thus was able to remain in Vienna all during the war years. [5]

Members of the extended Hirschmann family lived in two five-story apartment buildings constructed by their father around 1900. Karl Hirschmann with his wife Maria Huber inhabited an apartment in the building at Linke Wienzeile 156 in District VI. Their children were Erwin, Walter, Charlotte, and Friedrich. Karl’s building was back-to-back with a similar building that faced Mollardgasse. His brother Konrad lived in an apartment in that building with his wife Aloisia Huber. Their children were Kurt, Irmgard, Wilhelm, and Alfred. The two wives were sisters—daughters of Johann Huber, one of the great pioneers of the LDS Church in Austria. It was Johann’s farm in Rottenbach near Haag am Hausruck where a number of significant events took place from his baptism in 1900 through the end of the war. [6] The Hirschmann children (and cousins) from Vienna were frequent visitors at the Huberhof over the years. [7]

Kurt Hirschmann (born 1921) explained that the family walked about fifteen minutes to church from the apartment houses on Linke Wienzeile and Mollardgasse because the streetcars did not run in the direction of the Seidengasse. [8] The attendance was sixty to seventy persons. Sunday School was held in the morning and sacrament meeting in the evening. MIA took place on Tuesday nights.

As an older teenager, Kurt could not get a job. Thus it happened that he was assigned by the government to work in faraway East Prussia. Very unhappy with the program (“five months of work and no pay”), Kurt learned that the trip home on the train would cost thirty-five marks and he wrote to his grandmother for the money. She sent it and Kurt slipped away from the work camp one day and boarded the train for Vienna.

Before the war, the Vienna Branch had a small orchestra. Erwin Hirschmann (born 1924) recalled that he and his brother Walter both played the violin, as did Hans Vaculik and Heinz Teply. Erwin taught a Sunday School class for youth fourteen to sixteen and also served as the Sunday School president. As he recalled, “It was in this branch that I literally grew up. It was here that I became a deacon, a teacher, a priest and then after the war, an elder.” [9]

The connection with Germany had an immediate impact on young Wilhelm Hirschmann (born 1930), as he explained:

When Austria was annexed to Germany, I was eight years old and was immediately sent to Germany to live with a family. The government said that I would be safer there. My parents took me to the train station and said good-bye. We didn’t know where I would be sent. There were not many children left on the train when it got to Wolfenbüttel. The Kletzer family took me in when I got off there. They were very nice to me. I stayed in Wolfenbüttel for six weeks. I liked the time there. I thought that I could tell the family a little about the Church I attended at home, but they were not interested. [10]

An enlightening report is found in the Church History Library in Salt Lake City detailing the home-teaching efforts of the Vienna Branch on September 17, 1939: nine brethren were assigned to visit a total of sixty-nine families. As of the date of the report, the home teachers had seen an average of seven families each month. This is the only such report filed in the West German Mission. [11]

Shortly after the Anschluss in 1938, the Straumer family arrived in Vienna from the Free City of Danzig. [12] Johannes Friedrich Straumer was a major in the German army and commanded a tank battalion stationed in Vienna. His family was assigned an apartment at Grinzinger Allee 17 in District XIX. His wife, Bertha Lisa, had joined the Church in 1926 and immediately sought contact with the Saints of the LDS branch at Seidengasse 30. Her daughters, Brigitta and Erika, also attended branch meetings and activities on occasion. [13]

Brigitta Straumer (born 1923) recalled that the Germans who arrived in 1938 to direct the transition of Austria into the National Socialist world were not resented by the local residents. In her recollection, “The Germans were the conquerors but I don’t think that the Austrians felt that they had been conquered. Many of them wanted us [Germans] there. They wanted to be part of Germany.” [14]

Her sister Erika (born 1926) agreed that there was no animosity shown them as German citizens. However, she perceived a difference between her family and the local members of the Vienna Branch: “They were mostly poor and I looked down on them a bit because of our [higher] standing.” The Straumers’ neighborhood in District XIX featured higher-class buildings that allowed them a beautiful view north into the Vienna woods. [15]

Brigitta Straumer wanted to learn to dance and showed the necessary aptitude at an early age. By 1940, she had been accepted to the Academy for Music and Dramatic Arts in Vienna, where she studied under the famous Grete Wiesenthal. Johannes Straumer was not a member of the Church and felt that Brigitta should not be baptized until she was an adult, but she had been taught the principles of the gospel by her mother and practiced the LDS lifestyle—at times a challenge in the world of the performing arts. For the time being, it was still “Mutti’s church” to Brigitta. [16]

Erika Straumer became a member of the BDM (League of German Girls) in 1940. She recollected,

We had a big rally once in downtown Vienna and we had to march all the way there [from District XIX]. Eventually, I grew tired of the activities and began to stay away. But in order to receive my grades at the end of each semester, I had to tell [the school authorities] which group I belonged to, so I asked my friends to tell me what they had been doing recently. For a while, the BDM leaders kept track of me.

It appears that at Easter time in 1939, Gertrude Mühlhofer was living a charmed life. Given a comfortable vacation at a ski resort, she met a handsome young soldier, Fritz Klein, a native Berliner who had moved to Vienna. As she recalled, “He was not a member of the Church back then, and I told him there would be no hanky-panky before marriage. He respected that and I give him credit for that to this day.” Thus began a two-year long-distance courtship for Gertrude and Fritz. She returned to her work in Vienna and he was sent to the Soviet Union.

The Mühlhofer-Klein wedding took place under irregular circumstances. Fritz had been severely wounded in Russia and wrote Gertrude in July 1941 that he had lost his left leg. She traveled to his hospital near Frankfurt, and they decided to marry. It was September 17, 1941, and she described the setting in these words: “They decorated a [hospital] room for us and it was really pretty. There were red roses on the walls and nice fabric as decoration. And there were gifts on the table from his comrades.” Fritz was soon transferred to a hospital in Vienna, and the newlyweds went home soon thereafter.

After escaping from the work program in East Prussia, Kurt Hirschmann found a position in a trade school just two blocks from his home. From late 1938 to 1941, he attended school there and worked toward graduation as a machinist. Just a week after graduating, he received his draft notice and was mustered into an artillery unit of the German army on April 4, 1941. Initially, he was sent to Karlsruhe, Germany, for five months of training. While there, he attended meetings with the Karlsruhe Branch whenever possible and recalled singing enthusiastically “with mostly old people.” In the fall of 1941, Kurt had three weeks of furlough and spent the time helping his Grandfather Huber on the farm at Rottenbach near Haag. From there, he was sent to the Soviet Union, where German forces were experiencing great success. As he recalled,

It was [in Russia] that I learned that there is a God. You wonder sometimes how come you’re still alive. One day we had stopped to arrest a man in a small house when dive-bombers swooped down to attack us. We were safe in the house, but bombs hit our car. When the attack was over, the motor was lying in the middle of the road and some tires were hanging in a tree. It all happened in a minute and it was a very faith-promoting experience. . . . When God wants us to live, he finds a way for it to happen.

Walter Hirschmann (born 1921) finished his studies in an engineering school in Vienna in 1939 and found employment with the AEG Company. A year later, he was drafted and sent to Stuttgart, Germany, to be trained as a radio operator. By the fall of 1941, he was with the forces attacking Moscow, Russia. “When we reached that point [the outskirts of the city], we could not seem to go on,” he recalled. Fortunately, he developed an abscess on his arm and was sent back to Austria for treatment. He was still there in January 1942 when his father passed away. [17]

Back in Russia a short time later, Walter stayed only six months. During that time, he fired his weapon only at night and “only as a kind of defensive measure,” as he described it. He was never wounded but there were instances where he thought it was his time to die. Fortunately, he was sent to Berlin to work with the Siemens Company, a huge electronics firm. “I kept my uniform but did not have to wear it. I worked in a department responsible for developing equipment to jam the navigation devices of British and American airplanes heading for German cities. We wanted to distract them from their bombing runs but were never able to carry out the plan.” While in Berlin, Walter attended church meetings and was ordained a priest.

Wilhelm Hirschmann recalled a sign in the window announcing the presence of the Vienna Branch. He explained that the sign had a specific impact in one case:

That sign attracted a family to the Church, and they joined during the war. They had been resettled from somewhere in Ukraine to Vienna because the government believed that they were in danger after the German army went through their area, maybe in 1941 or 1942. The mother of that family went looking for a church and saw our sign in the window. She knew instinctively that this was to be her church. Their name was Ivanitschi.

The family of Johann Friedrich Docekal was assigned a new apartment in 1941. His daughter Martha recalled that in November 1941, a woman who was assigned one of the rooms in their apartment told them, “They’re coming to get them tonight,” to which Maria Docekal responded, “I want to know what they’re doing.” Quietly opening their window, the Docekals watched as Jewish families living in apartments downstairs were taken from the house and put into an open truck. Each person was carrying a bundle. According to young Martha, “We knew that they were Jews, because we had seen them in the hall with the Star of David [on their coats].” Martha had seen Jews in the streetcars around town wearing the Star of David and had asked herself, “What have they done that they have to wear that?” [18]

For all practical purposes, there were three active holders of the Melchizedek Priesthood in the Vienna Branch who stayed at home during World War II—the branch presidency, consisting of Alois Cziep, Johann Ackerl, and Anton Körbler. The rest were serving in the military. Fortunately, several young men held the Aaronic Priesthood and attended meetings regularly, which was a great help to the branch presidency. During the war, two boys and one man were ordained deacons (Wilhelm Hirschmann, Heinz Martin Teply, and Stefan Meszaros), one was ordained a teacher (Josef Cziep), and four were ordained priests (Johann Schramm, Erwin Hirschmann, Roland Paleschka, and Stefan Meszaros). Johann Vaculik was the only man ordained to the office of elder. Attendance at priesthood meetings averaged about eight men during the war. [19]

Just as Alois Cziep worried about and cared for the members of the branch, his wife Hermine Cziep was the president of the Relief Society and had the same concerns. Throughout the war years, she walked countless miles across town to help the sisters with their babies, children, and illnesses when needed. She often expressed gratitude to her longtime counselors, Maria Hirschmann and Maria Docekal. The three were often seen in the branch rooms on Saturdays cleaning up and arranging things for the Sunday meetings.

Erwin Hirschmann had wanted to become a farmer (perhaps like his Grandfather Huber), but was a very good student as well. He finished public school with high marks and was enrolled in a state trade school, followed by a term of study at the Technical University of Vienna. Work internships took him for a few summer months to Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance and to Stuttgart, both in Germany. In March 1942, he went to work for Siemens and Halske in Vienna. On December 12, he was drafted into the Wehrmacht. Following boot camp in Braunschweig, Germany, he was sent to Belgium and then to France, where he became seriously ill with pleurisy. He was transfered to Vienna and then to a town close to Salzburg for nearly two months of treatment and recuperation. [20]

Membership in the Nazi Party was also the experience of several members of the Vienna Branch. At least two of the Hirschmann boys were required by their employers to join, but neither took part in Party meetings or activities. The branch president was not a member of the party, but according to his daughter, Emmy, one of his counselors was, and Brother Cziep had to deal with at least one political incident in Church during the war:

Brother —— was a church leader who came to visit us from Germany. I remember his name and I even remember what he looked like. . . and he wore the Nazi Party button on his lapel. He came to our district meeting, and he gave a prayer and prayed for Hitler. My father got up right after him and said, “I’m sorry, Brother —— but in this Church, in this branch, we do not pray for Hitler.” That is the only political statement I remember hearing my father make. I heard this with my own ears, and it impressed me because I was a member of the Hitler Youth at the time. [21]

According to Emmy, her father instructed the Saints in Vienna that they were to pray for their families, the members of the Church, and the safety of the soldiers, “but not for Adolf Hitler!”

Nazi Party politics could not be totally avoided by the branch leaders. Alois Cziep recalled that “some of our best members were also party members or sympathizers and I had to go to great lengths to keep politics away from the Church.” One of his greatest challenges was to ask Sister Weiss and her son, who were Jews, to stay away from the meetings “because we would have lost our meeting place at once” if they were seen entering the building wearing the Star of David, as was required by law beginning in 1941. Brother Cziep visited Sister Weiss in her home until she and her son were deported to Poland, where he believed they were killed. [22]

Fig. 3. The Cziep family lived on the third floor to the right of the corner in this building on Taborstrasse. (E. Cziep Collette)

Fig. 3. The Cziep family lived on the third floor to the right of the corner in this building on Taborstrasse. (E. Cziep Collette)

Like other young people in the Reich, Emmy Cziep was required to be a member of the Jungvolk, but while there were strict duties, there were also privileges. “We could ride the streetcar for free, get out of school for parades, and do all kinds of things. And who doesn’t like a uniform when you’re ten years old? I thought it was beautiful. We had a dynamic leader and she was great. Had it not been for her I probably wouldn’t have liked it as much.” Looking back on the experience, Emmy realized that the girls were asked subtle questions that might have elicited dangerous answers, such as: What’s your parents’ favorite radio program? Who comes to visit and what do they talk about? What do you talk about at home?

Emmy did not recall any problems connected with her membership in the LDS Church, but there was an incident at school relating to religion. The teacher was dictating text to be written by each student and stated that there was no God and that Jesus was a figment of the imagination. Having learned many short quotations on religion from her parents, Emmy blurted out, “The glory of God is intelligence!” The teacher began to mock Emmy by asking her to explain the statement, which she could not do. “I had no way of explaining,” she said, “so I felt like a fool.”

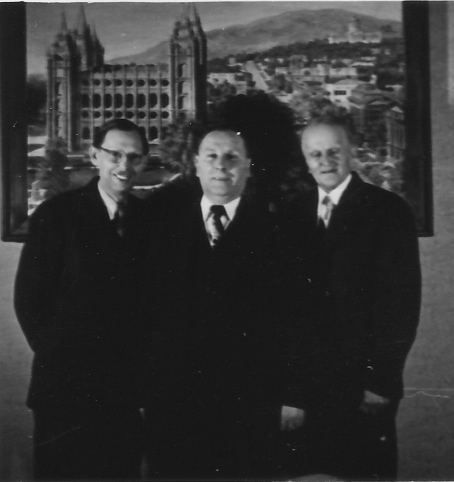

Fig. 4. The presidency of the Vienna Branch. From left: second counselor Johann Ackerl, president Alois Cziep, first counselor Anton Franz Körbler. (G. Koerbler Greenmun)

Fig. 4. The presidency of the Vienna Branch. From left: second counselor Johann Ackerl, president Alois Cziep, first counselor Anton Franz Körbler. (G. Koerbler Greenmun)

As in other LDS Church branches throughout Germany and Austria, this branch also celebrated births, baptisms, and weddings. Five children of record and converts were baptized during the war: Martha Docekal, Anton Alfred Vaculik, Marianna Przybyla, Brigitta Straumer, and Erika Straumer. Three weddings were also celebrated among the members of the branch: Gertrude Mühlhofer and Friedrich Klein (1941), Margarethe Czerney and Hans Wabenhauer (1941), and Johanna Mayer and a Mr. Richter (1942). [23]

Martha Docekal (born 1933) recalled her baptism in the Old Danube (an inactive arm of the Danube left over when the course of the river was regulated): “We were baptized, changed our clothes, and then we were confirmed at the same location.” Anton Vaculik (born 1934) remembered that some friends of the branch owned a small cabin there and allowed the Saints to use it as a dressing room for baptismal ceremonies. [24]

In 1942, Johann Vaculik (born 1902) was drafted into the Wehrmacht and had to close his delicatessen store. At the age of forty, he found basic training to be very strenuous, but was then assigned noncombat duty. Stationed in Vienna, he rode the train as an army policeman (Zugwache) who checked the papers of military travelers while looking for deserters and saboteurs. His travels took him to Germany, France, Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece. Brother Vaculik continued to enjoy duty away from the battlefield, being assigned to a supply company and doing guard duty in Russia and Poland in 1943. [25]

By the summer of 1942, Brigitta Straumer had progressed sufficiently in her dance studies to be sent with a group of dancers to perform for German soldiers in occupied Poland. The girls had to be cautious in the large city of Posen, because the Poles were understandably unhappy under the German occupation. Brigitta had no difficulties on the trip but recalled clearly the occasion when they boarded a streetcar for a ride through the Jewish ghetto and were told by German soldiers to not take any pictures:

I will never forget that ride, what I saw and how I felt. . . . I was indoctrinated by Hitler and had certain feelings about the Jews. From the streetcar we could look and see the city streets and the people on the streets. I saw that many of the men wore long beards and black long coats, such a strange sight. . . . This was a ghetto for Jews. They couldn’t leave the place. They were prisoners there. I did not feel sorry for them, but thought that it was all right to have all the Jews live together in one place. Oh, what had Hitler’s teaching done to me, a nice 19-year-old girl? . . . I did not see the suffering of the people, nor did I want to. [26]

While still in Posen, Brigitta learned of the death of her brother, Second Lieutenant Hans-Joachim Straumer, in Russia. He was killed on August 8, 1942, not far from where his father was serving with a tank brigade. Bertha Straumer was devastated by the news but never faltered in her dedication to the Church and the branch. According to Brigitta, “the death of my brother started a slow change in me. I had been selfish, mostly thinking of myself, dancing and performing.” Watching her mother serve without interruption after Hans-Joachim’s death, Brigitta wondered where her mother received her strength. “Deep down, I knew the answer. It was the Savior, Jesus Christ, His love and atonement.” [27]

The branch general minutes show that the leaders and members put forth a serious effort to maintain the programs of the Church during the war. For example, branch conferences were held the first week of December in 1941, in 1942 (with mission supervisor Christian Heck), and in 1943 (“an excellent success”). The Mutual classes for young women and young men were combined in October 1942, and a study of the book Teachings of the Gospel by Joseph Fielding Smith was initiated. This was a great benefit to the youth, because the MIA classes in most branches of the West German Mission had been discontinued by that time. The Sunday School also held periodic conferences and even organized a membership drive in November 1943. [28]

President Cziep wrote of the progress of the war in these words:

At first it seemed that Germany was going to win. It didn’t take long and no one could hide the hard facts! Food and necessities became scarcer and the black market was in full bloom. [Hitler was] always asking for more men and at last it was young boys and old men that were asked to bear arms. More and more wives and mothers heard the message that their husbands and sons were not going to return. As long as the bombing attacks were confined to the German cities, we viewed those people as heroes. But then when the hail of fire and iron fell over the cities of Austria, hopelessness, chaos and destruction became our reality. No one could dream of living a normal life! [29]

In December 1942, Kurt Hirschmann came home to Austria on leave and married his sweetheart, Johanna Dietrich of the Frankenburg, Austria, Branch. He had met her before the war when her family lived in Haag am Hausruck and attended church there. It would be nearly two years before he could see her again. In the meantime, his constant prayer had been answered: “I prayed that I would not be taken prisoner by the Russians. Maybe God could help me be wounded just badly enough that I would be sent away from Russia,” he recalled. “On August 26, 1944, my prayer was answered when I was hit in the head by shrapnel.” Loaded onto an ambulance wagon at the last second, he was saved from the advancing Red Army and was eventually sent to a hospital near Hanover in northern Germany.

Kurt’s head wound was not serious and he assumed that he would be sent back to the fighting soon. Fortunately, an army doctor kept him in the hospital for a month and then transferred him to a second hospital for another month. “I didn’t need to stay that long after he removed the piece of metal—two weeks at most. [While I was there,] my wife came from Austria to see me. When she walked in she looked like an angel.”

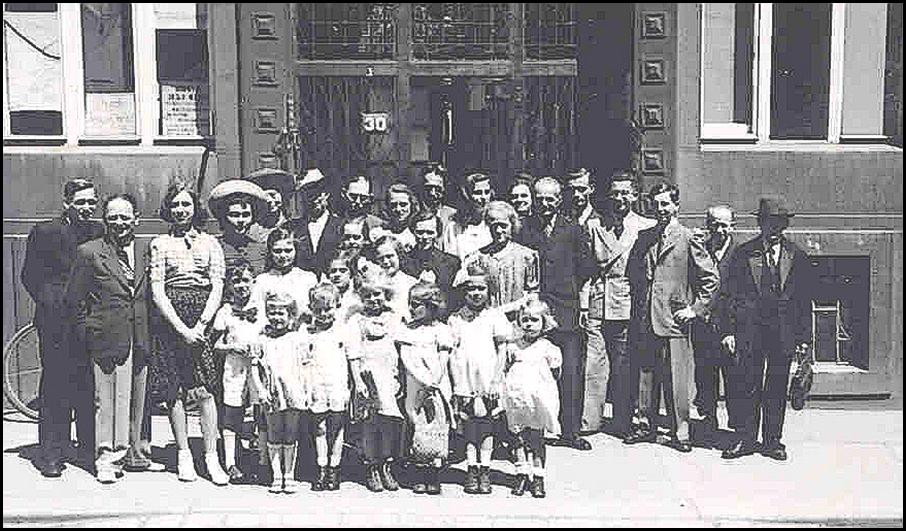

Fig. 5. Members of the Vienna Branch at the summer home of Maria Hirschmann in Purkersdorf in 1943. (E. Cziep Collette).

Fig. 5. Members of the Vienna Branch at the summer home of Maria Hirschmann in Purkersdorf in 1943. (E. Cziep Collette).

By the spring of 1943, Erwin Hirschmann had recovered from his bout with pleurisy and was assigned to a unit in Braunschweig again. He requested and was granted a transfer to Hanover and made the move just one day before his unit in Braunschweig was sent to a combat zone in Russia. He wrote, “I readily admit that this transfer to my reserve unit as opposed to my combat unit most likely saved my life. . . . In Hanover, our specialty was in the area of microwave communications . . . using magnetrons and klystrons for wireless transmissions.” From Hanover, the group moved to Flensburg near the German-Danish border and from there to nearby Plön. [30]

From the summer of 1943 to the spring of 1944, Brigitta Straumer became increasingly interested in religion and her mother’s church and attended LDS meetings more often than before. It took the Straumers forty-five minutes via streetcar to go to Church, and Sister Straumer often made extra trips. On one occasion, Brigitta was washing the big windows in the main meeting room and asked her mother, “Why do we have to do all this [cleaning]?” The humble answer was, “Tomorrow is conference and the spirit of the Savior cannot dwell in an unclean building.” Bertha Straumer always dressed in her finest for Church and often took flowers to spruce up the rooms. [31]

On a cool day in May 1944, Brigitte Straumer was baptized in the Old Danube. It was raining, and she had prayed for a clear day. Her prayer was answered by the time she joined branch president Alois Cziep in the chilly water; the clouds parted and the rain stopped for a moment. After changing clothes, she sat on a chair under an umbrella while Anton Körbler confirmed her a member of the Church. “I had a wonderful feeling being so clean, all my sins were forgiven. I wanted to stay that way the rest of my life.” Soon after her baptism, Brigitta was in the Netherlands on another dance tour and had the opportunity to successfully demonstrate her dedication to the word of wisdom while attending parties where alcohol was abundant. [32]

In early 1944 the officials of the Vienna city government anticipated frequent air raids and encouraged parents to take their children out of town to safer areas. Martha Docekal was taken by her mother to a small town about forty-five minutes from Frankenburg where there was an LDS branch. Martha was quite unhappy in the local school, where the teachers were not good as compared with her teachers in Vienna. To make matters worse, she was soon accused of skipping Jungvolk meetings, which could cause serious difficulties with local police. Her mother then gave her money for soup so that she could stay in town for the meetings. The long walk home in the dark of winter was hard for Martha, but she was soon pleased to learn that girls who lived more than a mile or two from Frankenburg were exempted from attending Jungvolk meetings.

Anton Vaculik turned ten in 1944 and was inducted into the Jungvolk. One major responsibility given the youngsters was to solicit funds for the Winterhilfswerk (winter relief fund). Anton recalled taking his little sister along when he attempted to fill his tin can with coins: “When the people saw this little girl, they were very generous in giving. I took her all around the Gürtel (one of the major streets around the city center), and we stood in front of every store. Pretty soon we had our can full of coins.”

In general, Anton enjoyed the Jungvolk experience. The boys were encouraged to participate in sports, and he became very good at the long jump. This may have been a reason for Anton’s candidacy for attendance at the famous Ordensschule in Sonthofen, Germany, where the next generation of Nazi leaders was to be trained. As he recalled, “One day, three men in uniform came to our school. They took [three of] us to the music room and told us to take our clothes off. It was cold in there, and we stood there stark naked in front of these three guys [for inspection].” [33] Anton was later informed that all three had been selected to attend the Ordensschule, but his mother strenuously objected and he remained in Vienna.

As the war dragged on, the number of attendees at Sunday meetings of the Vienna Branch decreased significantly. The branch general minutes show an average attendance at sacrament meeting of thirty for 1943 and twenty for the first few months of 1945. Many Saints who called Austria’s capital city their home were at war all over Europe or had left the city in search of safer conditions. Others could no longer safely make the trip across town when public transportation was increasingly unreliable and the threat of attack ever-present.

One of those families split apart by the war was that of Anton Körbler, a counselor to Alois Cziep in the branch presidency. Anton was a government employee and was thus required to remain in Vienna, but his wife, Stephanie, took their children, Gerliede and Peter, to the small town of Neuhaus on the German side of the Inn River. It was the fall of 1943 and while life was becoming increasingly challenging in Vienna, the war was still far away from Neuhaus, where the Körblers lived at the Fischer Inn. A year later, they moved across the river to house no. 248 in the Austrian town of Schärding. Totally isolated from the Church, Sister Körbler taught her children Bible stories and sang hymns with them. Gerliede (born 1936) recalled that there were many things to do in Schärding. She even saw Adolf Hitler there in the fall of 1944 when he made one of his last public appearances. [34] Sister Körbler only returned to Vienna on one short occasion before the war ended: Gerliede was baptized there by her father in the Old Danube in the fall of 1944.

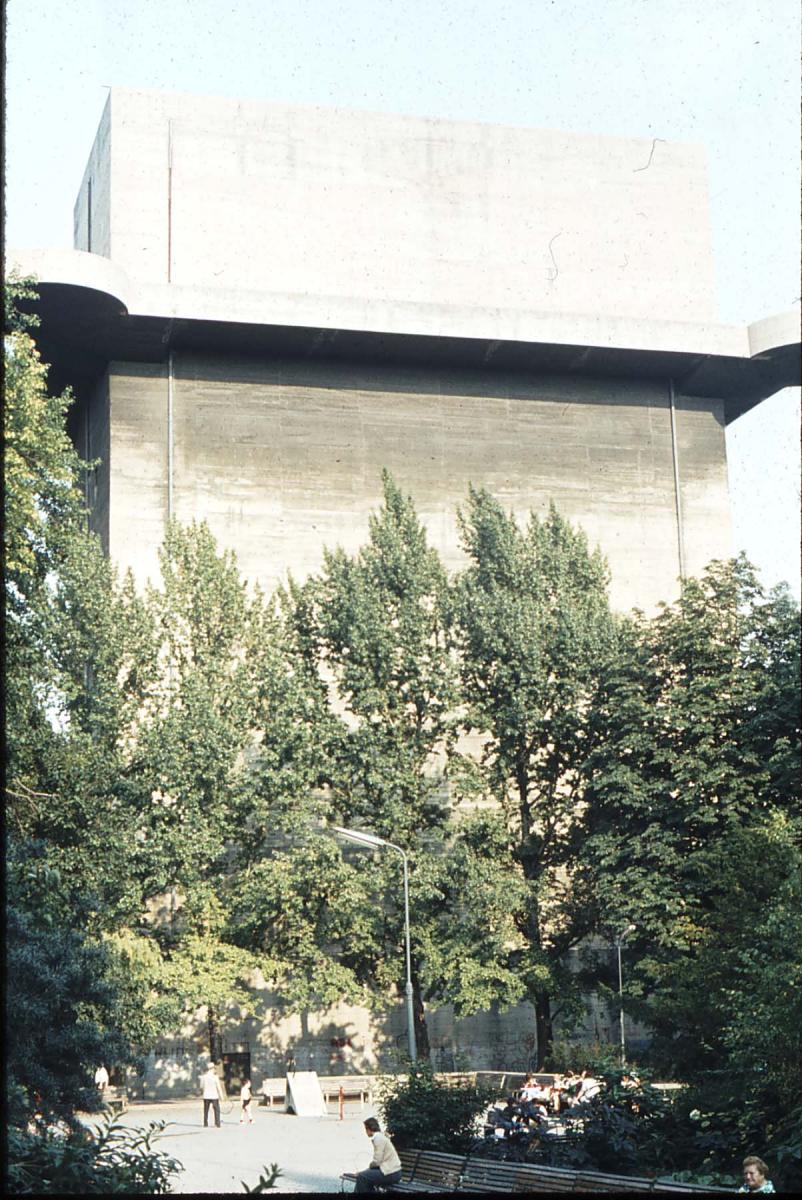

Fig. 6. This eight-story air-raid shelter/

Fig. 6. This eight-story air-raid shelter/

When Vienna came under attack from the air, Alois Cziep was assigned as the air-raid warden for his building. It was his job to see that all twenty-eight residents went down into the basement each time an alarm sounded. When they left their apartment, they carried their most important papers along in case they had to find shelter away from home. At church, the sacrament meeting that had been held traditionally in the evening was moved to a time just after Sunday School so that branch members only had to make the walk to Church once each Sunday. Brother Cziep later wrote, “Many times we would have air raids in the middle of one of our meetings and I would lead the members to the shelter for safety.” [35] The branch history lists alarms on February 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, and 18, 1945, and actual attacks on February 19–23. [36]

President Cziep kept a small metal box next to the door of the apartment and instructed his family to make sure that the box was taken by whomever was home into the basement shelter when an alarm sounded. The box contained membership records, tithing funds, and bank records. The branch president was determined to preserve order in the Church in Austria no matter what happened to him or his apartment. [37]

Fig. 7. Alois Cziep kept Church records and money in this box in his apartment. (CHL)

Fig. 7. Alois Cziep kept Church records and money in this box in his apartment. (CHL)

By the time the air raids over Vienna were beginning to lay waste to large parts of the city, Anton Vaculik was ten years old. “After the first attack, I nearly had a nervous breakdown. I stared out the window all day long. In the evening I just broke down. . . . Our apartment house was damaged and the building next door was totally destroyed. Seven dead people were pulled from the rubble there and I watched [the rescuers] do it. Then my mother got angry because I was watching.”

Anton specifically recalled Sunday, September 10, 1944:

We never went to the shelter on Sunday because nothing ever happened. Suddenly the bombs hit, and I went down to the cellar with two big suitcases. I was right next to the cellar door when the bombs hit, and the pressure threw me into the cellar. So we were sitting in the cellar praying, and I said, “I’ll be good, Father in Heaven. Don’t let me die!”

According to Brigitta Straumer, the war came to Vienna “for real” in 1944. Sitting in air-raid shelters while bombs burst outside was frightening, and she wondered if her family members elsewhere in the city would survive and if their house would be standing after the attack. On at least one occasion, Brigitta and her mother made their way past burning buildings and saw people emerge from shelters in panic. The young convert recalled that church meetings were at times were interrupted by sirens. When bombs landed in the yard of her home one day, it seemed as if she and her mother (who had delayed their trip to the shelter in the basement) would surely die. [38]

Wilhelm Hirschmann’s school in Vienna was closed in 1944, and he was sent to Haag am Hausruck to live with the family of branch president Franz Rosner. From there he could take the bus to a school in nearby Ried. By February 1945, he was back at home and found that during his absence, two bombs had struck and partially damaged the adjacent buildings in which he and his cousins lived. He recalled how the families of those two buildings gathered in the basement with his Aunt Maria in Linke Wienzeile 156: “[During air raids] my aunt had us singing and praying when we sat in the basement. The other residents of the house were Catholic, but my aunt was our spiritual leader during those hours and they respected her.”

Fig. 8. This hole is the wall at Linke Wienzeile 156 led into the neighbors' basement, as required by civil defence regulations. (R. Minert, 2008)

Fig. 8. This hole is the wall at Linke Wienzeile 156 led into the neighbors' basement, as required by civil defence regulations. (R. Minert, 2008)

Walter Hirschmann never met another LDS soldier while at the front. His comrades knew that he did not drink alcohol or smoke, as did his colleagues at the Siemens Company “and they respected that,” he recalled, “Sometimes there were discussions about that topic, but they never made fun of me.” By early 1945, Walter was back in Austria, near the city of Linz on the Danube River.

Having finished public school at age fourteen, Emmy Cziep was assigned service under the government’s Pflichtjahr program. Fortunately, she found herself in the home of an LDS family with several children, where her presence enabled the mother to be employed. She lived with the family for a year and took the children to church on Sundays. “I was fortunate to have this assignment,” she recalled. Her diary indicates that the Pflichtjahr lasted from July 17, 1943, to July 17, 1944.

The military experience of young Josef Cziep (born 1926), son of the branch president, began at age sixteen. He decided to enlist because this allowed him to choose the Luftwaffe (air force) where he was assigned as a truck driver. While serving on the Western Front, he wrote to his family in Vienna. Four of those letters reflect his state of mind in October 1944. From Detmold, Germany, on October 6, he informed them that he had been transferred to the Waffen-SS: “I at once went to the Lord and asked him to help me so I won’t have to go to the SS. I also know that this prayer will be answered if it is the will of the Lord. . . . I have only one wish—to escape this chaos of war safe and sound and to be able to perfect myself in different areas.” [39] Still agonizing about his involuntary move to the Waffen-SS, Josef wrote on October 12 from Freistadt, Germany: “A song from the Church keeps coming to my mind: ‘If the way be full of trial, worry not, if it’s one of sore denial, worry not.’ I have nothing else but to trust the Lord in His help.” Four days later, he wrote again: “I have been close to despair were it not for the support of the Church. The circumstances under which we live here are so very primitive. No water, no toilet, no beds, just straw spread out.” [40]

Four days later, Josef Cziep had already been moved to Poland and wrote to his younger sister, Emmy. His spiritual orientation was still strong, as is clear from his instructions to her: “As you leave Vienna in January and are going to be only surrounded by your school friends you will have many occasions when you will be tempted and when prayer will be your support. That’s when you will prove to yourself how strong you are in keeping the commandments. . . . Let the Lord help you in all things and be willing to acknowledge his help.” [41]

The letter written by Josef on December 17, 1944, again reflects his peaceful inclinations. He had just been assigned to a sniper unit: “I hope never to be in this position, but should it occur I just don’t know how I should act. I could never shoot a person. . . . I have [been inspired] to use all free minutes I might have in reading church books. . . . That we will soon be at the end [of the war] is clear to me.” [42]

Fig. 9. Young Emmy Cziep sold such items as these (actual size) on the streetcars of Vienna to raise money for government programs. “Anybody who didn’t buy one from me risked looking unpatriotic.” The machine-stitched medallions show native Austrian costumes from various regions on the country. The booklet, The Führer and the Winter Relief Program, has thirty-two pages. (E. Cziep Collette)

Fig. 9. Young Emmy Cziep sold such items as these (actual size) on the streetcars of Vienna to raise money for government programs. “Anybody who didn’t buy one from me risked looking unpatriotic.” The machine-stitched medallions show native Austrian costumes from various regions on the country. The booklet, The Führer and the Winter Relief Program, has thirty-two pages. (E. Cziep Collette)

Johann Vaculik was allowed a furlough at Christmas 1944 and was thus at home when his daughter, Marianne Christine, was born on December 23. His unit was then transferred to the Western Front to face the Americans in their steady advance toward the Rhine River. Just before the Americans captured the last bridge over the Rhine at Remagen on March 7, Brother Vaculik became a prisoner of war. He and his Austrian comrades were separated from the German POWs and sent to camps in Stenay and LeHavre, France. In a rare instance, he met another Austrian LDS soldier, Heinz Teply from Vienna. Their experience as POWs included the typical poor housing conditions and food, but having lost the war, they did not expect anything better. [43]

Fig. 10. The Cziep family: Hermine, Emmy, Mimi, Alois, and Josef. (E. Cziep Collette)

Fig. 10. The Cziep family: Hermine, Emmy, Mimi, Alois, and Josef. (E. Cziep Collette)

With Brother Vaculik gone most of the time, his wife depended heavily on her son, Anton. She even sent him to the office of the civil registrar to report the birth of her newest son. The name of the baby boy was supposed to be Johannes Bartel, but the registrar objected to the name. Thinking of the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Anton selected the name Johannes Wolfgang for his infant brother.

In late 1944, Kurt Hirschmann was released from the hospital and rejoined his artillery unit near the city of Hamburg. There he attended meetings in the Altona Branch. A teacher in the Aaronic Priesthood, he had been away from Church meetings for nearly two years, and his only connection to religion had been personal prayer and a Bible he protected carefully. While in Hamburg, Kurt experienced the air raids that had terrorized the city’s residents for years. He recalled the first such instance: “I had never seen anything like it. The basement walls shook just like a ship in a storm. I wondered how long it would last and if the whole building would collapse on top of us. This was a war against [women and] children.”

Erika Straumer had enjoyed her life as a teenager in Vienna. She had advanced into a secondary school and had time to go to movies with friends. By the time she joined the Church in September 1944, she had also experienced a marked improvement in her attitude toward the gospel. During a vacation among relatives in Germany, she and Brigitta had become lost in a forest at night and prayed for direction. The answer reminded Erika that she too was dependent upon God, who answers prayers. However, in the fall of 1944, her life took on a more serious character when she was drafted into the national labor force and taken out of school. She was assigned to a camp at Buch near Innsbruck, Austria, where she and her comrades assembled small parts for aircraft. All her connections to the Church were suddenly lost.

Erika was given a new assignment in the Reichsarbeitsdienst in January 1945 and transferred to Rankweil, Austria, near the Swiss border. Three weeks later, word was received that the French army was approaching from the west and that the enemy soldiers had a very poor reputation for their treatment of conquered civilians. With the Soviets approaching Vienna from the east, Erika dared not go home but took a train to Innsbruck instead. Upon arrival, she called the home of a friend from her camp and asked to be taken in. They kindly agreed, but Erika had to leave when the American army arrived and quartered soldiers in the home. Her next refuge was a mountain home where she was required to work for her board, but at least she was safe. From there, she wrote to Franz Rosner of the Haag am Hausruck Branch for news about Vienna members; he knew nothing about her mother or sister in Vienna, but he informed her that her father was safe and living with the family of district president Johann Thaller in Munich.

The Klein household had been blessed with a son, Friedrich Heinz, on September 28, 1942. However, the fortunes of life apparently turned against Gertrude and Fritz when their son contracted tuberculosis. Expecting her second child in days, Gertrude demanded to take her sick son home from the hospital and succeeded despite the objections of the medical personnel. Gertrude felt that her son could pass away under better conditions at home than away and proceeded to push his baby carriage through the snow uphill to their apartment. “I talked to my son constantly, telling him to not fall asleep,” she recalled, but he did on April 6, 1945. A few days later, her second child was born.

In January 1945, Emmy Cziep was in Gloggnitz, about fifty miles south of Vienna. She had been sent there with about one hundred school girls (of whom she was one of the oldest) after their Vienna school had been destroyed. In Gloggnitz they heard loud noises in the distance and were initially told that it was the sound of German army maneuvers. Later, their leaders admitted that it was actually the Red Army approaching. The girls were then instructed to leave immediately in whatever direction they pleased and Emmy headed straight for home. “When I got back [to Vienna], the Russians were very close behind us. It was announced that they were at the outskirts of the city. I told my parents that we had to leave town, but my father said that as branch president he had to take care of the members and that we could not leave. He said that Father in Heaven would take care of us.”

On April 5, 1945, a bomb struck the building in which the Cziep family lived. Fortunately, only the upper floors were damaged and the Czieps were not rendered homeless. Members of the branch spent a great deal of time in shelters praying for deliverance while the sirens wailed and bombs were heard landing all over town. [44] With the arrival of the Red Army in April 1945, street battles were the order of the day for an entire week. When the fighting subsided, one source of terror was simply replaced by another—the conquerors’ search for booty and evil amusement.

Like thousands of other parents in Vienna, Alois and Hermine Cziep agonized about the safety of their daughters. Mimi and Emmy were twenty-one and seventeen respectively when the war ended and as such were prime targets of marauding soldiers. Fortunately, their hiding places were never discovered and they managed to escape every threatening situation in a Vienna that seemed to have no rule of law for several weeks after it was conquered. [45] “We went up to the [attic] time and again and hid behind the chimney because the Russians were raping everybody they could get their hands on. It was horrible. We had two sisters [in the branch] who were raped several times.”

Just weeks before the war ended, the commander of Erwin Hirschmann’s communications unit near Plön in northwestern Germany informed his men that the war was lost and issued them (illegal) release papers. They buried their weapons and equipment, found civilian clothing, and began to make their way to their various homes. Erwin’s path led him south through areas conquered by the British and the Americans, while he carefully avoided any contact with the approaching Red Army. In the meantime, he and a comrade also had to keep a close watch for SS soldiers who were fanatically pressing German men and boys into a hopeless defensive effort and were quick to execute anybody who disobeyed. By July, Erwin had reached the German-Austrian border, where he was detained by American soldiers. Fortunately, he was able to convince them to call his uncle, Franz Rosner (the LDS branch president in Haag), who convinced the guards that Erwin was a native of Austria. The young former soldier then rode his bicycle to the Huber farm in Rottenbach, where he helped with the harvest of 1945. Erwin had never seen combat and had therefore never fired his rifle at an enemy. [46]

The war ended in a very peaceful fashion for little Gerliede Körbler in Schärding, Upper Austria. “It was kind of strange. We were not even home when the Americans came into town. We were out picking raspberries. When we came home, we found two bundles of our things in front of the house.” When American soldiers moved into the building, Stephanie Körbler and her children were suddenly homeless. Competing with many other refugees in the area, she found several temporary quarters in succession while she also worked hard to gather enough food for the three of them. She was displaced a second time by American soldiers and on another occasion she had to break into her own garden (locked up by the conquerors) to get food for her children. All the while, the Körblers had no contact with other Saints and did not see Anton until the late summer of 1945. He had lost his job with the government in Vienna. From Schärding he sought contact with the members of the Frankenburg, Haag am Hausruck, and Linz Branches in an attempt to help restore order there.

Fig. 11. Vienna Branch at the end of World War II. (E. Cziep Collette)

Fig. 11. Vienna Branch at the end of World War II. (E. Cziep Collette)

With the war over and a kind of disquieting peace settling over Vienna, the leaders of the branch were determined to gather their flock together again. President Cziep recalled that they had to go in search of the members on foot, assured that anybody riding a bicycle would lose it in minutes to Soviet soldiers. Local men were also being arrested and sent east as forced laborers. So it was that the brethren made their way through rubble-laden streets to the apartments of the Saints. “Imagine our joy when we would find a brother or sister and realize that almost none of the members had suffered seriously. How the Lord had his protecting hand over us.” [47]

Anton Vaculik recalled how the Red Army soldiers searched the family apartment: “After only a few days, they came into our apartment with an Austrian interpreter. There were three Russians. We hurried out of the basement because the fighting was over, and we were told we could get out. The Russians came in with a long probe. They would open up the wardrobes and stick it in to find things we had hidden. My mother was really upset.”

Walter Hirschmann was fortunate to avoid the fate of a prisoner of war. When hostilities ceased in May 1945, he was still an employee of the Siemens Company and as such was not treated as a soldier by the invading Americans. Rather than leaving at once for Vienna (where the Soviet forces were in control), Walter stayed in the American occupation zone with his relatives in Rottenbach (Haag am Hausruck Branch). He did not see Vienna again for several years.

Somehow Josef Cziep had survived the end of the war on the Eastern Front and was back in Vienna by May 1945. However, his trials were not over, and his sister, Emmy, described what happened to him next: “May 8, 1945 Josef was abducted in Vienna by the Russians. Some holding areas were in open parks surrounded by barbed wire. We [Emmy and sister Mimi] looked for him in these prison yards but couldn’t find him. Many young men like him were sent on trains to Siberia. We went from one camp to another trying to find him. We didn’t know if he was still alive or not.”

In an attempt to convince the Soviets that Josef had been forced against his will into the Waffen-SS, the Cziep sisters shoed the Russians some of his letters (quoted above). The Soviets apparently assumed incorrectly that the Waffen-SS combat troops were similar to the SS police who had orchestrated the murder of millions of people in Eastern Europe. Fortunately, Josef eventually came home, as Emmy recalled: “Josef was released May 20, 1945 according to my diary. Josef couldn’t tell us what happened. He was told if he did, they would come and kill him. All we knew was that he was hung from his feet upside down and beaten within an inch of his life.” [48]

Bertha Straumer said many prayers for the safety of her daughters Brigitta and Erika when the Soviets arrived in Vienna. While Erika was still away from home, Sister Straumer devised hiding places for Brigitta in their apartment building. When soldiers searched for victims, Bertha Straumer was an equally enticing subject, but the safety of her daughter was her prime concern. On one occasion, soldiers beat her with the butts of their rifles and she suffered broken ribs. Another time, a soldier left his rifle in the family’s apartment and Sister Straumer had to smuggle it out of the building so that she would not be suspected of killing a Russian or stealing Russian property.

Life during the first few weeks after the war meant constant terror for Brigitta. She was accosted several times by soldiers bent on taking such things as watches and bicycles. Once, soldiers who seemed to be drunk searched the family apartment. Brigitta and a girlfriend were hiding in the bathroom when a soldier entered. He looked straight at the girls but apparently did not see them. Brigitta was holding a Book of Mormon close and praying all the while for protection and was grateful to see her prayer answered so dramatically. One day, she went to a well for water when enemy soldiers came by. A neighbor who understood Russian heard the men speak of their plans to follow Brigitta home. The neighbor warned her to take a different route, which she did by means of many delays and detours. Fortunately, the soldiers were called away before they could discover where Brigitta lived. “When they were out of sight, I hurried home, shaking all over,” she recalled. [49]

During the summer of 1945, Erika Straumer was able to travel to Salzburg, where she joined the LDS branch. A member of the branch took her in and soon she was united with her father. Johannes Straumer had survived the war and contacted his wife in Vienna in August 1945. Unfortunately, he was imprisoned by the Americans for sneaking across the border from Germany into Austria. When Sister Straumer heard about this stroke of bad luck, she was convinced that he would become converted to the gospel while in prison. She told Brigitta, “This will be the way your father will be humbled, and then he will be ready to accept the Gospel of Jesus Christ.” He did soon thereafter. [50]

Erika was finally able to join her family in Vienna in December 1945. She had traveled without legal papers from Linz in the American occupation zone to Vienna in the Soviet occupation zone, risking serious punishment if she were caught. “The people sitting next to me on the train had given me their permit so that I could get through. The Lord works in mysterious ways.”

The branch meeting rooms at Seidengasse 30 survived the war intact and the members of the Vienna Branch met for a testimony meeting on May 6, with twenty-three in attendance. They looked forward to a time when they could hold their worship services in peace. The first report of a major event in the branch tells of a spring conference held on July 1, 1945. The mission history has this comment: “Spring conference under the direction of Branch President Elder Alois Cziep. Theme: ‘Repent, for the kingdom of Heaven is nigh at hand!’ The pronounced influence of the Holy Ghost was felt by all present.” [51]

Kurt Hirschmann was taken captive by the British near Lüneburg, Germany, in May 1945 and shipped to Belgium as a POW. He was not fed very well but knew instinctively that POWs in the Soviet Union were much worse off and was again grateful for the wound that had rescued him from duty at the front. His greatest trial as a prisoner was a lack of activity, so he sought opportunities to volunteer for work details. On March 14, 1946, he was released and sent by train back to Austria. There he saw for only the second time his two-year-old daughter, whom he hardly knew, and also visited his Grandmother Huber at the farm in Rottenbach. They had enjoyed a very close relationship, and he was pleased to see her just before she died.

Johann Vaculik was relieved to be put on a train bound from France to Austria in the fall of 1945. However, a cruel trick was played on him when the train stopped at the German-Austrian border by Salzburg and the POWs were transported back to Stenay, France. In February 1946, he was again heading east and made it all the way to Vienna. In Wegscheid, he was “fed by the Americans and brought up to a less-than-normal weight. They were embarrassed to show us off as skeletons when we came home to our families.” Entering his neighborhood in Vienna, he found that his family’s apartment had been damaged in the bombing and the windows were covered by cardboard. He later wrote, “When I arrived it was quite a surprise for Maria and the children. The kids were quite underweight but had been helped by the LDS servicemen . . . with some of their own rations, coal, money, and lots of candy at Christmas.” In church he had a “wonderful homecoming with my brothers and sisters in the gospel.” With little delay, Brother Vaculik opened up his store again and began a new phase in his life. [52]

Anton Körbler brought his wife and two children back to Vienna in 1946. Their apartment was still there, but the windows had been shattered by the air pressure produced by bombs landing nearby. After three years of isolation, Sister Körbler and her children were very happy to be associated with the members of the Vienna Branch once more.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Vienna Branch did not survive World War II:

Karl Friedrich Hirschmann b. Vienna, Austria, or Rottenbach, Oberösterreich, Austria, 18 Oct 1892; son of Konrad Hirschmann and Anna Maria Zeh; m. 31 May 1920, Maria Huber; d. tumor Vienna 3 Jan 1942 (K. Hirschmann; AF, PRF)

Friedrich Heinz Klein b. 28 Dec 1942 Wien, Austria; d. tuberculosis 6 Apr 1945 Klosterneuburg, Niederösterreich, Austria (M. Mühlhofer Klein)

Florentine Sartori b. Wien, Austria, 4 Oct 1878; dau. of Edward Sartori and Barbara Kiessl; bp. 17 Oct 1928; conf. 17 Oct 1928; missing as of 20 Mar 1944 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 782; FHL microfilm no. 245257; IGI)

-—Sztraszeny b. ca. 1915; m. ca. 1936–37; 2 children; k. in battle (E. Cziep Collette, M. Docekal Vaculik; M. Mühlhofer Klein)

Marianne Christine Vaculik b. Wien, Austria, 22 Dec 1944; d. Bad Hall, Austria, 23 May 1945 (Vazulik)

Notes

[1] Anton Körbler, “Geschichte der Kirche Jesu Christi der Heiligen der letzten Tage in Österreich,” (unpublished history, 1955). Used with the kind permission of Gerlinde Koerbler Greenmun.

[2] Alois Cziep, autobiography (unpublished), 84.

[3] Gertrude Mühlhofer Klein, interview by the author in German, Kiesling, Austria, August 9, 2008; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[4] Emmy Cziep Collette, interview by the author, Idaho Falls, Idaho, June 10, 2006.

[5] Cziep, autobiography, 74, 87.

[6] See the Haag am Hausruck Branch chapter for more about Johann Huber.

[7] Eric Hirschmann provided the genealogical details presented in this paragraph.

[8] Kurt Hirschmann, interview by the author, Ogden, Utah, March 2007.

[9] Erwin Hirschmann, “A Full Life Well Lived” (unpublished autobiography); private collection.

[10] Wilhelm Hirschmann, interview by the author in German, Vienna, Austria August 9, 2008;

[11] Vienna Branch general minutes, CHL LR 9781 11.

[12] For a description of the Anschluss (the annexation of Austria by Germany), see the Vienna District chapter.

[13] Brigitta Straumer Clyde, “Biography of Brigitta Emmy Maria Straumer Clyde” (unpublished autobiography, 1996), 30.

[14] Brigitta Straumer Clyde, interview by the author, Logan, Utah, July 29, 2008.

[15] Erika Straumer Anderson, telephone interview with Roger P. Minert, March 31, 2009.

[16] “Biography of Brigitta Emmy Maria Straumer Clyde,” 27.

[17] Walter Hirschmann, interview by the author in German, Munich, Germany, August 6, 2008.

[18] Martha Docekal Vazulik, interview by the author, Draper, Utah, March 7, 2007.

[19] Vienna Branch general minutes.

[20] Hirschmann, “A Full Life Well Lived.”

[21] The name of the man was given in the interview but is withheld here by the author.

[22] Cziep, autobiography, 81. Several eyewitnesses recalled the Weiss’s family, several members of which attended meetings of the Vienna Branch. Sometime during the war, the Weiss’ disappeared. Nothing is known about their origins or their fate.

[23] Vienna Branch general minutes.

[24] Anton Vazulik, interview by the author, Draper, Utah, March 7, 2007. The surname was spelled “Vaculik” in Austria.

[25] Johann (John) Vazulik, “World War II Memories of John Vazulik” (unpublished history); private collection. Used with permission of Anton Vazulik.

[26] Clyde, “Biography of Brigitta Emmy Maria Straumer Clyde,” 40–41.

[27] Ibid., 41.

[28] Vienna Branch general minutes.

[29] Cziep, autobiography, 87.

[30] Hirschmann, “A Full Life Well Lived.”

[31] Clyde, Biography of Brigitta Emmy Maria Straumer Clyde, 45.

[32] Ibid., 43.

[33] Anton later learned that the men were likely determining that none of the boys had been circumcised—something very rarely done among Christians at the time.

[34] Gerliede Körbler Greenmun, telephone interview with the author, January 12, 2009. Hitler returned to Berlin in January 1945 and never again left his headquarters in the city’s center for another large public event.

[35] Cziep, autobiography, 88.

[36] Vienna Branch general minutes.

[37] Emmy Cziep Collette donated that valuable heirloom to the LDS Church History Museum.

[38] Clyde, “Biography of Brigitta Emmy Maria Straumer Clyde,” 45

[39] Josef (“Joschi”) Cziep, letter to his parents October 6, 1944, cited in Emma Esther Cziep Collette, Glen and Emmy Collette Family History (Brigham Young University Press, 2007), 226.

[40] Josef Cziep to his parents, October 12 and 16, 1944.

[41] Josef Cziep to Emma Cziep, October 1944.

[42] Josef Cziep to Alois Cziep, December 17, 1944.

[43] Johann (John) Vazulik “World War II Memories”

[44] Cziep, autobiography, 89.

[45] Cziep, autobiography, 92–93.

[46] Hirschmann, “A Full Life Well Lived.”

[47] Cziep, autobiography, 97.

[48] Emma Esther Cziep Collette, Glen and Emmy Collette Family History, 226.

[49] “Biography of Brigitta Emmy Maria Straumer Clyde,” 48.

[50] Ibid., 49.

[51] Vienna Branch general minutes.

[52] Johann (John) Vazulik, “World War II Memories.”