Stuttgart Branch

Roger P. Minert, “Stuttgart Branch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 437–452.

For centuries, the city of Stuttgart was the capital of Württemberg, the largest state in southwest Germany. In 1806, Napoleon raised Württemberg to the status of kingdom, and Stuttgart became home to royalty. Although relegated to secondary political status when the German Empire was founded in 1871, Württemberg remained a proud component of the new Germany, and Stuttgart was its principal jewel. In 1939, the city had more than 490,000 inhabitants. [1]

The Stuttgart Branch consisted of 197 registered members that year and was therefore the largest unit of the Church for miles around. One in six of those members held the priesthood, and with eighteen elders, the branch was in a position to render support to weaker units of the Stuttgart District.

| Stuttgart Branch [2] | 1939 |

| Elders | 18 |

| Priests | 0 |

| Teachers | 5 |

| Deacons | 10 |

| Other Adult Males | 21 |

| Adult Females | 110 |

| Male Children | 18 |

| Female Children | 14 |

| Total | 197 |

The president of the Stuttgart Branch as World War II approached was Erwin Ruf. His counselors at the time were Karl Lutz and Wilhelm Ballweg. All leadership positions in the branch were filled: Karl Mössner (Sunday School), Friedrich Widmar (YMMIA), Erika Greiner (YWMIA), Julie Heitele (Primary), and Frida Rieger (Relief Society). Several other members were serving at the time in district leadership positions. [3]

Branch meetings were held in rented rooms in a building at Hauptstätterstrasse 96. Sunday School began at 10:00 and sacrament meeting at 7:00 p.m. The Primary organization met on Tuesdays at 5:30 p.m. and the Mutual at 8:00. The Relief Society met on Thursdays at 8:00. The fast and testimony service was held once each month immediately following Sunday School, and a genealogical study group met at 8:00 p.m. on the first and second Tuesdays of the month.

The building at Hauptstätterstrasse 96 was less than one mile from the center of Stuttgart, and the branch had moved into the rooms there on February 14, 1926. [4] Walter Speidel (born 1922) recalled that the church rooms were upstairs above a factory and that the missionaries had lived in back rooms before their evacuation. “I was the Sunday School secretary when the war started, and I remember writing attendance numbers in the 120s often. There might have been seventy to eighty persons in the sacrament meetings.” [5]

The Stuttgart Branch was one of only three in all of Germany that had a baptismal font in the meeting rooms. [6] This one was described by several eyewitnesses as a large tub. The chapel in the rooms at Hauptstätterstrasse 96 had a rostrum, according to Ruth Bodon (born 1927): “And my father donated a piano. The seats were individual chairs rather than benches. There was also a picture of Jesus on the wall, and I think there was a sign [with the name of the Church] out by the street.” [7]

Esther Ruf (born 1929) recalled that there was also a pump organ in the main meeting room: “The piano was to the left at the front of the room and the pump organ to the right.” [8] Dieter Kaiser (born 1939) recalled that when Maria Ruf was playing the piano, “I would run from the back of the room to the front, sit on her lap, and snuggle up to her because she smelled so good.” [9]

Life for Germans in general was quite good in 1938, but this was not true for the Jews who had not yet left the country. Lydia Ruf (born 1923) recalled the event that signaled all-out war against the Jews in Nazi Germany—the Night of Broken Glass:

Early in the morning [of November 10, 1938] I happened to go downtown in Stuttgart and saw the demolished windows of the Jewish shops. They were looted and merchandise strewn around. The news on the radio indicated that it was the rage of the German people against the Jews that caused them to destroy the Jewish shops. However, some of us knew very well that the [SA] troops were responsible and not the German people. [10]

With the departure of the American missionaries in August 1939, Erwin Ruf was called to serve as the president of the Stuttgart District. He in turn called Karl Lutz to lead the Stuttgart Branch. President Ruf then proceeded to write a history of the Stuttgart Branch under the title “Memorandum for the Celebration of Forty Years of History of Our Beloved Stuttgart Branch.” With a date of 1899 for the founding of the branch, Ruf described in detail the challenges faced by the first missionaries and Saints in the city and in Württemberg. His final sentence reads: “I hope that [the Saints] will continue to sustain the new branch president, my former first counselor, and be obedient to him. If you do this, you are assured of the blessings of heaven.” [11]

“I can still hear [in my mind] the radio announcement about the beginning of the war,” recalled Walter Speidel: “‘The Poles have finally attacked us, and as of 5:45 this morning we are shooting back.’ We had thought that the Polish army would invade Germany, and one of my cousins had already been drafted.” A month later, Walter was called to serve in the national labor force, and by January 1941 he was wearing the uniform of the Wehrmacht. Before leaving for basic training with the army, he was asked to speak in sacrament meeting, then was given a blessing by branch president Karl Lutz. In that blessing he was promised that he would return “without harm to body or spirit.”

Maria Ruf (born 1923) recalled hearing the broadcast announcing the attack on Poland. She heard Hitler say that he would be joining his troops at the front. If something happened to him, he would be succeeded by Rudolf Hess, and if something happened to Hess, Hermann Goering would be the next leader. “Everybody was touched,” she recalled, “It made you hope that nothing would happen to them. I came home to find out that my dad was drafted. That’s what I remember from the first day of the war.” [12]

Maria had finished high school and was hired as a secretary in a bank in the summer of 1939. She was still a member of the League of German Girls at the time and recalled that without that membership, she would not have gotten the job. Once employed, however, she wanted out of the league and managed to achieve her goal. At the same time, the office manager insisted that if she were not a member of the league or the National Socialist Party, she would forfeit her job. As it turned out, the league would not take her back. In total honesty, she insisted that even if she joined the party, she would not attend meetings. Before the manager could put more pressure on Maria, he was drafted into the army, and the matter was forgotten.

When she finished public school in 1941, Ruth Bodon was first called upon to serve her Pflichtjahr for the nation. She was assigned to work in a home and assist with domestic duties, as she recalled: “The man was an engineer, and the woman had two children. I went there in the morning and home in the evening. [The program] was Hitler’s idea that you kind of get prepared for marriage and to be a good housewife.” Following her year of service, Ruth began an apprenticeship as a dental assistant, and this training lasted for about a year.

After his selection for the Afrika Corps, Walter Speidel noticed odd reactions from German civilians when they saw his brown desert uniform, something quite foreign to the German army. By early 1942, he was ready for what promised to be a lengthy deployment in North Africa. Before leaving, Walter considered becoming engaged to a sweet young woman of the Stuttgart Branch whom he had known for years and seriously dated for several months. However, her mother objected to the union at that time. Walter described the hometown farewell from his sweetheart in these words:

After MIA, and at the end of our walk home, we spent more time than usual to say good-bye in the dark entrance to the Gablenberg pharmacy. We held on to each other as if this would be the last time we would see each other ever again. She broke down several times and couldn’t stop crying. But in the end, we knew we had to part. So, after a long time, we pulled ourselves together, and finally walked hand in hand to Gaishämmerstrasse. We embraced and kissed one last time, and then she ran into her building. I turned around and walked briskly back to my streetcar stop. [13]

Nephi Moroni Lothar Greiner (born 1929) was in trouble with the Hitler Youth when his father did not permit him to participate in activities on Sundays. He told the youth leaders, “I will raise my own son, and we go to church on Sunday!” The Hitler Youth leaders threatened action, as Lothar recalled, “They put me through a kind of humiliating ceremony; they took the insignia from my uniform—it was sort like being drummed out of camp. I can remember that very clearly.” [14]

The records of the Stuttgart Branch in the Church History Library include two interesting documents issued by the office of the Lutheran Church in Stuttgart. The first bears the date October 22, 1941: “Anna Hilde Rügner née Armbruster, a bookbinder, born August 11, 1920, in Weil im Dorf has left the Lutheran Church. She plans to join the Mormons.” [15]

A few months later, a report was sent from the office of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church to the office of the Evangelical Lutheran Church District of Stuttgart. The report is a reminder that a change of heart (in either direction) can happen to LDS persons as well as persons of any faith:

May 22, 1942: The person named below wishes to be allowed to enter the Lutheran Church again: Mrs. Meta Wagner née Manz, born 12 August 1908 in Stuttgart, residing at Augustenstrasse 131. She joined the Mormon Church in 1926 because she wanted to marry a man who was a member of that church. However, she eventually married a Catholic man. She had the child born to her in 1941 baptized in the Lutheran Church and now wishes to reenter the Lutheran Church. The attached document certifies that she has left the Mormon Church. [16]

The Erwin Ruf family were modest people who did not try to attract attention. Esther found that if she attended Jungvolk meetings on Wednesdays, she could skip them in favor of attending church on Sundays and nobody would report her (“I was kind of shy anyway.”) In school her Old Testament (Jewish) given name could have been a reason for contention in Nazi Germany, but again she was able to avoid trouble. As she described the situation, “It wasn’t too bad being a member of the Church, but as the years went by you said less and less about religion. They classified me as ‘believing in God’ [rather than as Catholic or Protestant].”

At the completion of their schooling, German teenagers were often given instruction in formal dance, but Maria Ruf’s parents did not allow her to participate. Fortunately she was able to join with several other Latter-day Saints to learn under the tutelage of Max Knecht of the Stuttgart Branch. They even staged a small prom, with phonograph records rather than a band. However, it turned out that some of the branch members did not approve of dancing in the church and voiced their protests. According to Maria, during the war “life got rather serious. I don’t think I had a normal teenage life because of the war.”

From March 8 to May 25, 1942, Walter Speidel and his comrades were moved from Germany through Italy to Tunisia in northern Africa. They saw many interesting and historic sites on the way and likely wondered what it would be like to fight the British in the desert. Serving under Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, the “desert fox,” Walter was part of the communications team that worked to install and maintain radio systems and telephone lines.

Soon after his arrival, Walter was very close to the action. The German Afrika Corps was retreating slowly before the British from Egypt westward toward Tunisia, and soon the Americans approached their positions from the west. According to Walter, “The Afrika Corps was always desperate for fuel and ammunition because the British destroyed 60 percent of it on its way across the Mediterranean Sea.” [17]

Walter’s description of the combat situation on July 11–12, 1942, reflects what many LDS German soldiers felt at one time or another during the war:

The situation seemed hopeless. . . . For the first time, I thought that I might die. We knew we couldn’t defend ourselves against tanks with our rifles and machine guns. . . . I thought of the blessing I had received before I left Stuttgart. I was promised that I would not have to shed blood, that my life would be protected and be spared in the end. With every breath, I sent up to heaven one Stossgebet [quick, desperate prayer] after the other. . . . There was only one thing I knew I could do: Pray, pray, and pray some more. My life was in His hands. Without His protection, I could not survive. [18]

Maria Ruf recalled the many ways in which civil defense authorities asked the Stuttgart civilians to prepare for air raids: “Each family [in the apartment building] had some kind of job,” she explained:

I was designated as the messenger; it was my job to run to the police station to report if anything happened to our building. We had water in the attic space in case a fire started there, and everybody was supposed to have a small suitcase packed with our best belongings to take to the basement during an alarm. We also had a [hole] from our basement into the next building in case our [exit] was blocked.

Nearly all the Latter-day Saints in Stuttgart lost their homes in the many air raids that plagued the city. Ruth Bodon was living in the home of her uncle when the bombs landed very close. However, Ruth and her cousin had not taken the sirens seriously; while others in the building went to the basement shelter, the two girls went back to sleep. “All of a sudden I woke up and all hell broke loose!” she recalled:

We heard the bombs hitting and the antiaircraft shooting and we ran down to the basement in our nightgowns. My aunt who had so often made fun of us Mormons and Christians was down there praying to God for help. . . . Then the air raid warden came in and told us all to get out because the whole block was burning. . . . We had a container of water in the basement and we put our sheets in it and [put them over our heads and] then went out two at a time. We ran down the street and the houses were burning on both sides. It was just awful. My uncle’s family lost everything.

To Lothar Greiner, the worst thing about the war was that his family was separated. During air raids, he and his father were required to stay in their apartment building to fight fires while his mother and his sister went down the street to a large bunker. After their building was hit and destroyed one night, Lothar went to the bunker: “It was my sad task to tell my mother that we had lost everything. I found her in the bunker, and she exclaimed joyfully, ‘Lothar is here! Now we can go home!’ I told her that we couldn’t because there was nothing left but rubble.” Sister Greiner and her daughter were then evacuated to Waldenburg, a few miles to the east, but Lothar and his father were not allowed to leave Stuttgart. “It became my greatest wish,” he said, “to see my family united again.”

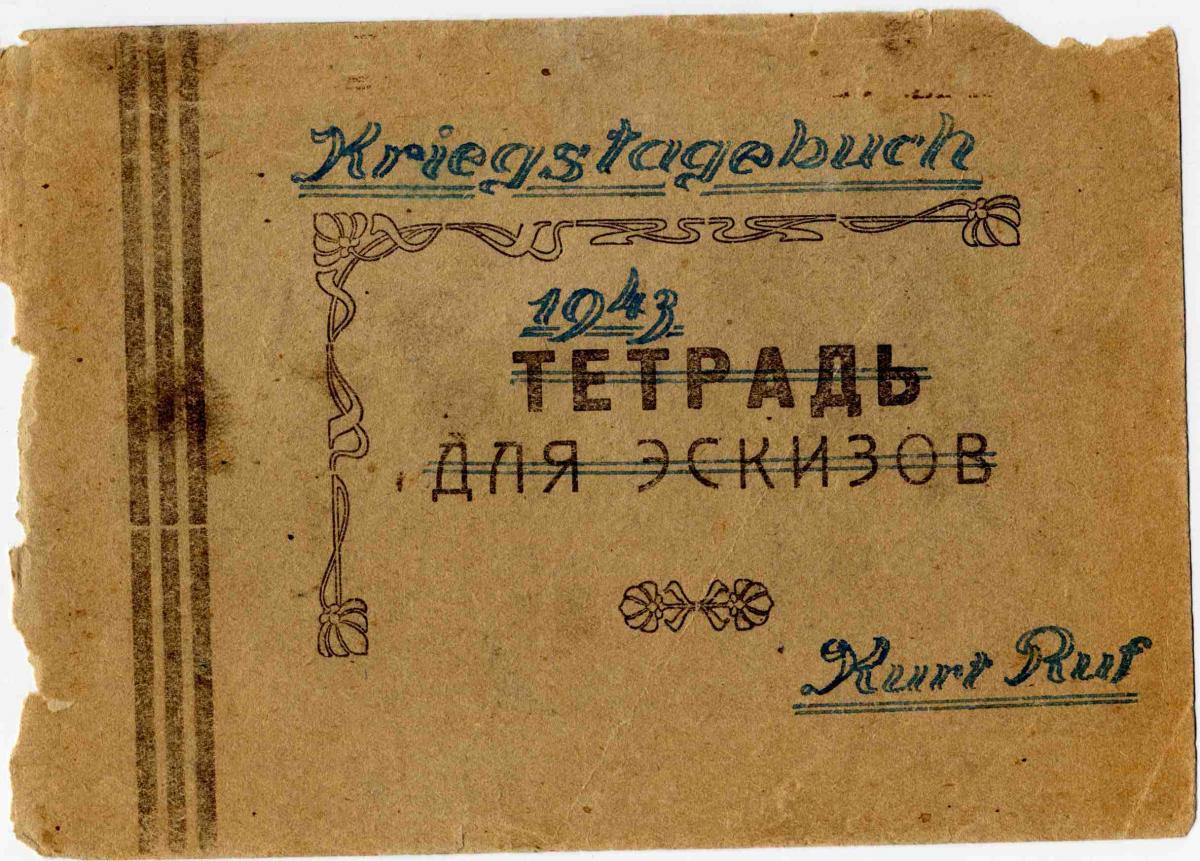

Fig. 1. Kurt Ruf used this Russian booklet for his diary in 1941. Kurt crossed out the book’s title and wrote “war journal, 1943, Kurt Ruf.” (L. Ruf Wright)

Fig. 1. Kurt Ruf used this Russian booklet for his diary in 1941. Kurt crossed out the book’s title and wrote “war journal, 1943, Kurt Ruf.” (L. Ruf Wright)

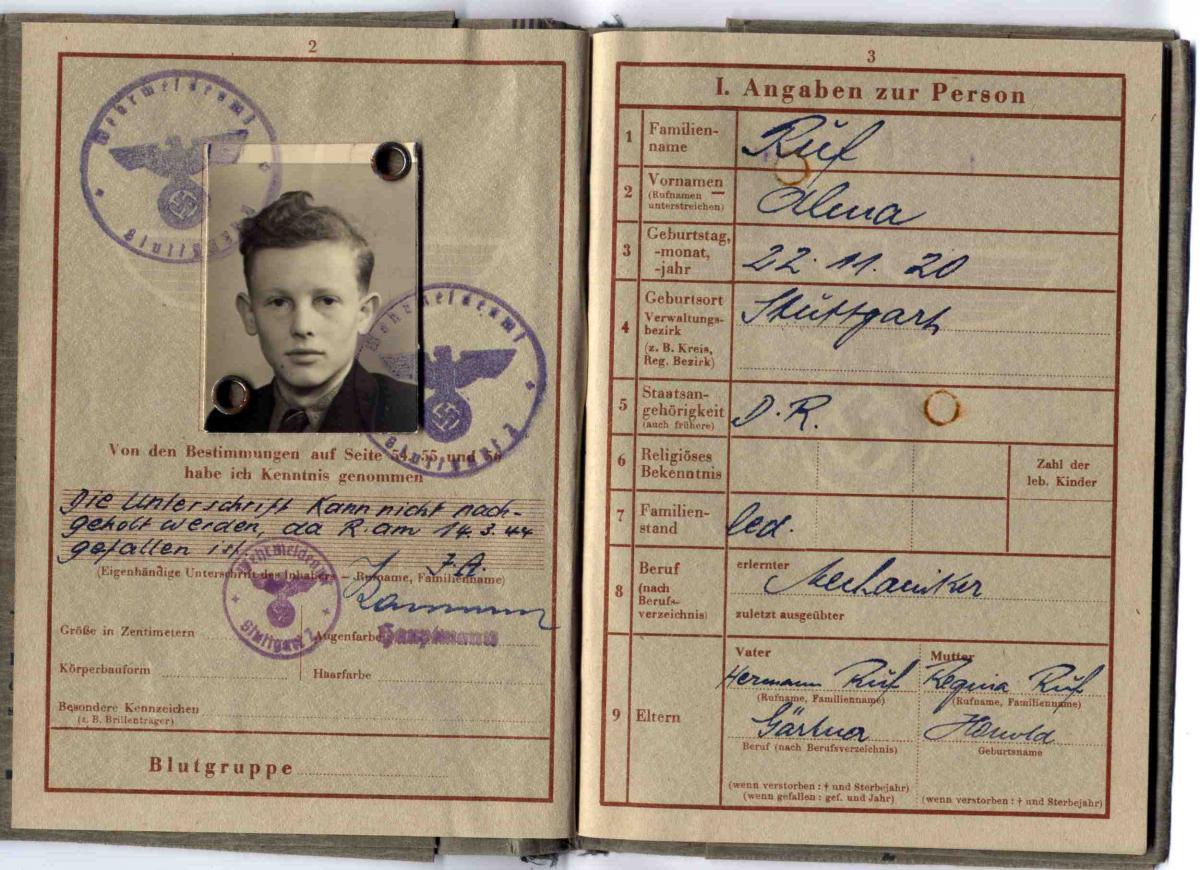

Lydia Ruf had hoped that her brothers, Kurt and Alma, who were both employed by the Robert Bosch Company (an important war industry), would be exempt from military service. Alma had even obtained a patent for a measuring device, but their work did not keep the two out of the war for long. Kurt decided to volunteer in order to choose his unit; he selected the tank corps. Alma was not drafted until 1944, and Lydia remembered his departure:

The last picture I have of him was taken at the [railroad station] in Stuttgart before he was shipped to Russia. There he stood in his uniform, leaning on his rifle—this fair-haired, young boy with the curly hair, who didn’t have a single violent bone in his body, going to war. We knew, as we looked on his face, that he would not return. His expression seemed to say the same. [19]

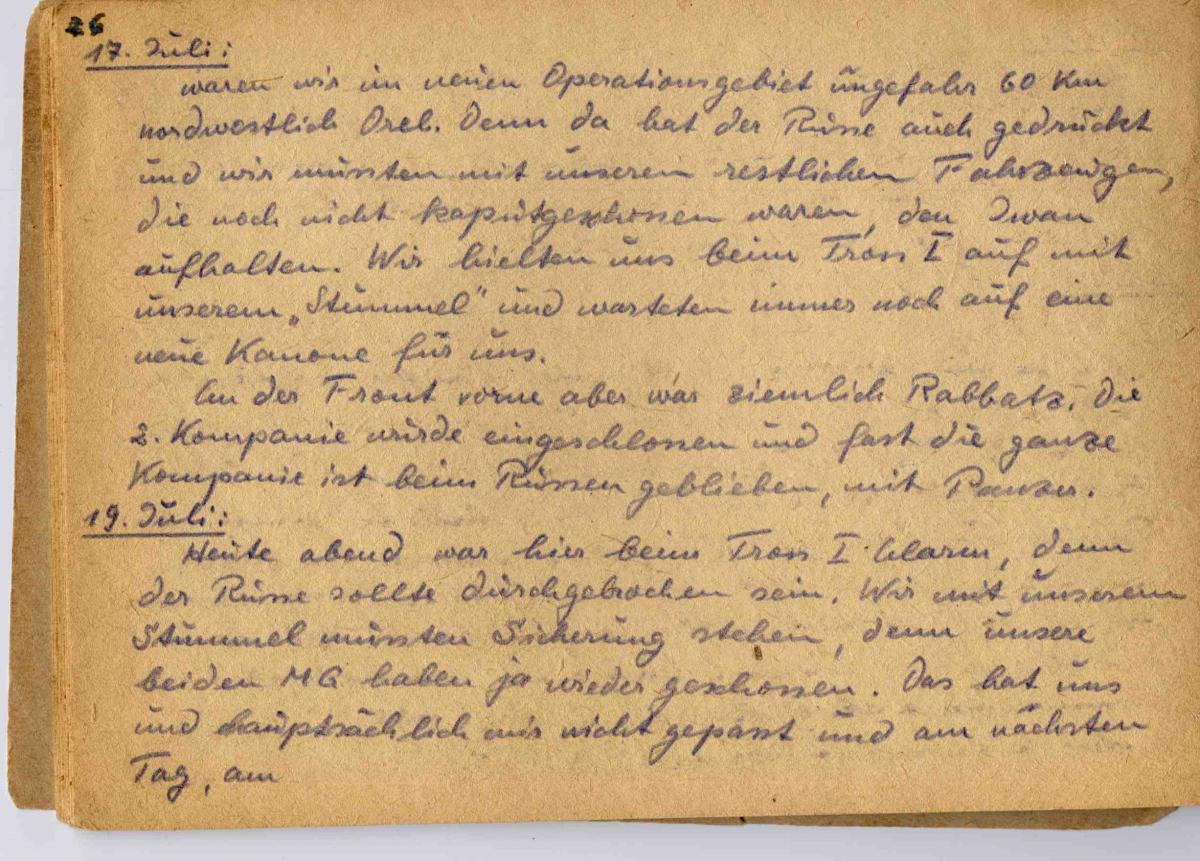

Fig. 2. A page from the highly detailed diary of soldier Kurt Ruf. (L. Ruf Wright)

Fig. 2. A page from the highly detailed diary of soldier Kurt Ruf. (L. Ruf Wright)

During their contacts “nearly every day,” Walter Speidel and field marshal Erwin Rommel learned that they were from the same part of Württemberg and enjoyed speaking their native Swabian dialect with each other. The field marshal also found out that Walter did not smoke or drink alcohol. In fact, on one occasion, the commander saw Walter’s copy of the Book of Mormon, picked it up, thumbed through it for a few moments, and then asked if it was a Bible. Walter’s response was a quick “Yeah, sort of,” and that was the end of the discussion. “My friends all knew that I was a Mormon,” he stated. [20]

District president Erwin Ruf was not allowed to leave Stuttgart, but he often sent his family away from the city to the safety of small communities. Anna Ruf had relatives in Deckenpfronn (twenty miles to the southwest), and she and her daughters spent significant time there. According to Esther, “I often took the train there by myself, even when I was only twelve. I thought I was all grown up. After getting off of the train, I still had to walk for an hour. It was kind of like a vacation for a few days. [But from Deckenpfronn] we could see Stuttgart burning [after air raids].”

“Every night at about 2:00 a.m. the sirens would go off,” recalled Harold Bodon (born 1936), “I was surprised that my dad let me go upstairs to watch the planes drop their bombs. I guess that was part of the curiosity factor.” Harold recalled seeing phosphorus burning and hearing people screaming in the street below. “It was getting very dangerous in Stuttgart, and our [apartment] house was the only one on the street that was not destroyed.” It was 1943, and for the family of Heinrich and Lina Bodon, it was time to leave Stuttgart. Brother Bodon received permission to move his business to his hometown of Waldsee, about one hundred miles southeast of Stuttgart.

Harold’s younger brother, Karl-Heinz (born 1937), also had vivid memories of the air raids and preparing for them:

Before we left [the apartment], we would go through a routine of covering all the windows and putting tape where there could have been some light seeping through. . . . I remember this old fellow who always came down into the basement shelter with some little toys, goodies, cookies, or what have you. It was all very orderly. Nobody seemed to get upset at all. We just all went down [to the basement]. We did it many, many times, and it was almost like a little get-together. [21]

The German Afrika Corps was eventually surrounded by Allied forces in Tunisia and Walter Speidel was taken captive by French Indochinese on May 12, 1943. Turned over first to the British and then to the Americans, he was transported by train through Algeria and Morocco, then to Tangier and Casablanca. A ship took him to New Jersey, and a train from there to Aliceville, Alabama, where he arrived on July 9. [22]

On the very day Walter was captured near the city of Tunis, his friend Kurt Ruf was thousands of miles away in the Soviet Union, writing the first entry in his new diary, entitled “My War Diary for the 1943 Campaign, Part I.” The first entry gives important insights into his attitude at a time when in the minds of many German soldiers it was no longer a certainty that the Soviets would be conquered:

May 12, 1943: I was just released from the field hospital after a week of reserve status. It is again time for me to serve. Today I joined with forty-nine other men for the trip to Russia. I cannot say that I was very happy about this because I really had it up to here with my first experience in Russia in 1942. But you have to obey in the army whether you want to or not. So I won’t mope around and will do the best I can to enjoy life.

Kurt said good-bye to his family in Stuttgart and boarded a train for the long trip to the Eastern Front. His diary is very detailed and provides information about his locations and activities on a daily basis. As the radioman of a tank crew, his fate was connected to the status of his tank. The great majority of his time in the summer of 1943 was spent in radio training and in waiting for repairs to be made on his vehicle. Meals, sleeping quarters, and weather were frequent topics in his entries, but there were of course accounts of combat, adventure, and danger, as is seen in his report of July 6. When Kurt’s crew encountered the Soviets that day, the Germans advanced with 104 tanks and “countless support vehicles.” Of course, the Germans respected the Soviet T34 tanks that opposed them. After two hours of fire, during which Kurt could not determine whether the noise came from the tanks to either side or from the enemy, he received a radio message indicating that his crew was to pull “vehicle no. 441” out of a huge crater close to their position. Initially, the men hesitated to leave the safety of their tank:

I said to myself, I have to go help my comrades. Who knows if some of them are wounded? So I decided to get out, and my heart was not even pounding. I opened my hatch, jumped out, and quickly got behind the tank. My buddies were right behind me—our commander and the other two crew members. Now there were four of us outside ready to help. We got our tow rope ready, but every time we stuck our heads out, the Russian sharpshooters were after us and we felt bullets whizzing by our ears. When we heard an artillery round coming our way, we hit the dirt and waited. Then we went to work again. I took one end of the chain, my buddy took the other, and we made ourselves as thin as possible and headed for the hook on the tank. The rope was too short, so we had to get another one. In the meantime, one of our crew got to the machine gun and kept the Russians busy for a few seconds. Finally we had the two tanks connected, and could start pulling him out. But, wouldn’t you know it? Our tank wouldn’t start. We had taken a hit from an artillery shell that knocked out our starter motor. [23]

Kurt’s detailed report indicates that they eventually got their tank started and hauled their friends out of the bomb crater.

The next combat action came after only a few weeks of waiting while their tank was repaired. All summer long, Kurt’s crew drove hundreds of miles as they maneuvered toward (and at times away from) the enemy. On one occasion, the crew accidentally filled their tank with diesel fuel instead of gasoline, and an officer accused them of treason. It turned out that a fuel depot assistant was the guilty party. It seemed that there was always something going wrong with the tank, and parts were extremely difficult to find.

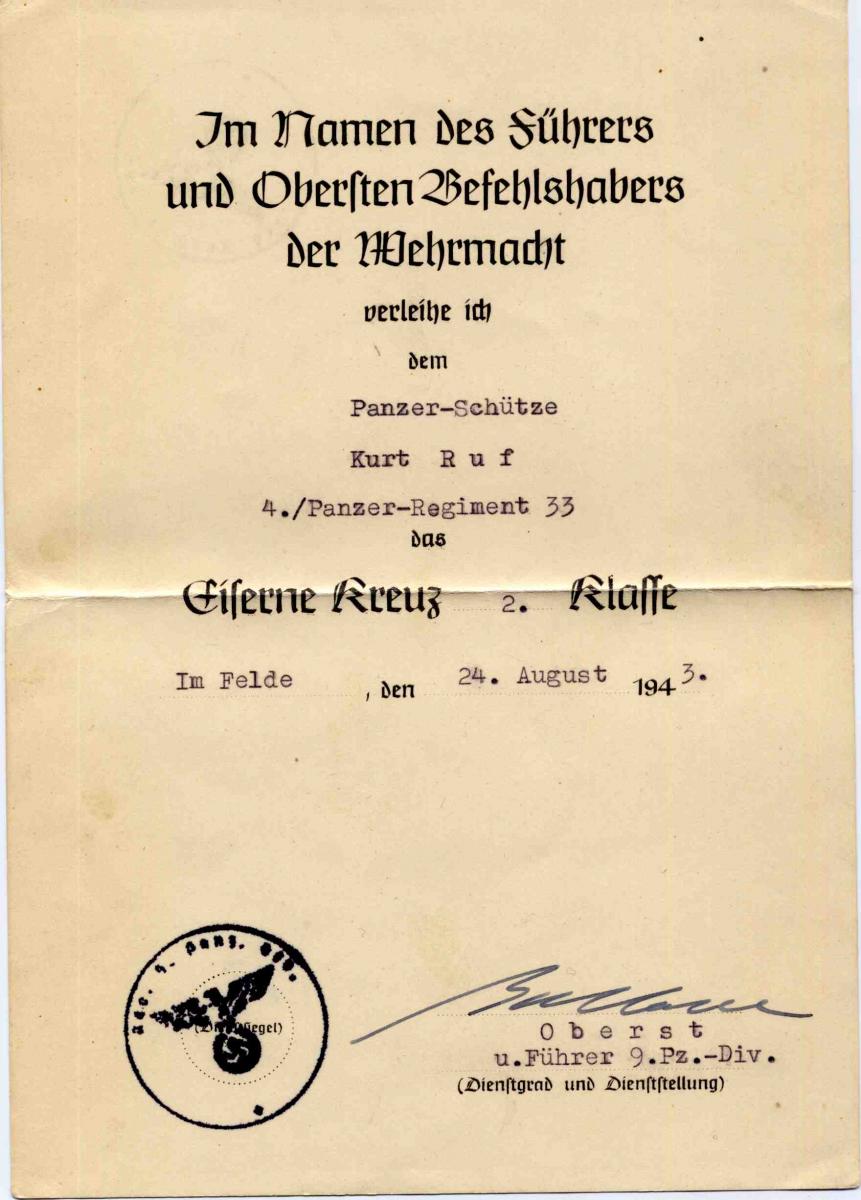

Fig. 3. Kurt Ruf was awarded the Iron Cross Second Class for valor in battle. (L. Ruf Wright)

Fig. 3. Kurt Ruf was awarded the Iron Cross Second Class for valor in battle. (L. Ruf Wright)

On August 1, 1943, Kurt Ruf was promoted to corporal, but things were not going well for his tank division. Three days later he wrote, “Every day we move back and leave more territory to the Russians without a fight. We have been eating all of our chickens, geese, ducks, calves, and pigs. Anything that could not be consumed was destroyed, including gardens and crops.” The Red Army pressed their enemy constantly, and Kurt was in combat on a regular basis. One day a cannon round penetrated his tank’s armor plate and shrapnel flew inches past his head, hitting his comrade. He understood just how close he had come to dying.

The air raid that devastated large parts of Stuttgart on October 7–8, 1943, also destroyed the church rooms at Hauptstätterstrasse 96 that had served the Saints so well for seventeen years. After that, it was seldom known much in advance precisely where the meetings would be held. According to Lydia Ruf, meetings were held in the forest in good weather:

Word got around that we should go to, say [streetcar] S-5 and the last station [“Georgsruh,” according to Lothar Greiner]. There we would meet in the woods for sacrament meeting, check to see what happened to everybody, and thus keep track of each other. Church members became very, very close. Everybody helped each other. . . . It was a great time of togetherness. Also, after losing it all, those who had formerly been deemed wealthy were just like all the rest. Now we were all equal. No one had any more than anyone else. War is a great equalizer. [24]

“The new year [1944] is here, and the front is on fire everywhere,” Kurt Ruf wrote. One of Kurt’s battles in early 1944 was against his comrades’ attempts to get him to drink alcohol. He resisted and ended up being the guardian of his drunken friends while his standards protected him. “I don’t need alcohol to make me brave,” he wrote, “I am my own master. I just had to laugh as I watched them break tables and chairs.”

Alma Ruf did not last long as a soldier. On March 14, he was killed in battle in the Soviet Union. Lydia described the reaction of the Stuttgart Branch: “When we heard about his death, there was a memorial service at church. It is customary in Germany to wear black to a service of this kind, but I refused to wear black. Somebody accused me by saying, ‘You’re not even grieving for your brother.’ I said nothing, but to myself I thought, ‘I should wear white because I had known him.’” [25]

Fig. 4. The military ID of Alma Ruf. (L. Ruf Wright)

Fig. 4. The military ID of Alma Ruf. (L. Ruf Wright)

In distant Waldsee, Heinrich Bodon continued to operate his fur business. Young Karl-Heinz recalled the following about the business:

People would bring us their dead foxes, . . . so we got all of those skins. Dad would work together with another firm to prepare the skins so that they could be made into fur coats. My mom and another lady sewed the furs together and made the coats. My dad and his brother took the coats to towns all around southern Germany and had two-day sales. They also sold muffs, caps, and collars.

Harold Bodon recalled that his father was also the town’s civil defense director—possibly a commitment he accepted in order to get permission to move his family out of Stuttgart. Brother Bodon wore the small round Nazi Party lapel pin, but did not maintain any loyalty to the party. The family initially lived in the Hotel zur Sonne in Waldsee, but later moved into a house at Stadtgraben 14. Harold was baptized near there on June 28, 1944, as he recalled: “It was a little creek. I remember that we were all dressed in white, and there were a lot of people standing about two hundred feet away. I think my father and [my brother-in-law] Kurt Schneider did the ceremony.” [26]

Heinrich and Lina Bodon were determined to raise their children in the gospel, despite the fact that Waldsee was a great distance from any branch of the Church. Every Sunday, they conducted a Sunday School in their home. According to young Harold, “My dad told us that if we participated [in Sunday School] he would take us either to a soccer game or to the movies in the afternoon. The soccer team was Schwarz-Weiss-Waldsee, and the movies were always about Hopalong Cassidy. That kept the family together. We learned a lot of good stuff, and eventually we made the right decisions [based on what we learned].” At the same time, the war went on, and Harold recalled that at school he and his classmates were given wooden rifles and taught to march: “We hoisted the swastika flag and goose-stepped and had a great time.”

Toward the end of the war, Dieter Kaiser’s father (not yet baptized) got in trouble with the strict Nazis at his work. He was employed in research and development, and his company employed several forced laborers from occupied countries. He had insisted to his superiors that the laborers needed better food and medical treatment, but his protests fell upon deaf ears. One night, an air raid threatened the prisoners, and Herr Kaiser let them out of their incarceration. In Dieter’s recollection, “My dad came home with holes burned in his white shirt. If he had not let the prisoners out, they would have been killed by the bombs. The next day, I went with my father to the railroad station; he was now a private in the army and was headed to the Eastern Front.” The message to troublemakers was clear: toe the party line or suffer the consequences.

Young Dieter understood the dangers of airplanes above Stuttgart. Barely five years old, he was once knocked off of a table during an air raid and needed stitches to close the gash on his head. While in the hospital, he managed to reopen the wound and needed more stitches. On another occasion, he was out fetching milk for his mother and was attacked by an American fighter plane. “The pilot fired at me with his machine gun, and I dove into a ditch to get out of his line of fire. I hit something hard and spilled the milk. When I got home, I had a bent milk can and my knee was bleeding. My mother [spanked] me because I hadn’t been paying good enough attention.”

The Erwin Ruf family experienced several terrifying nights when the bombs landed in their neighborhood. One bomb actually hit the corner of their building but did not explode. Another raid left their entire street on fire. When Lydia and her mother emerged from their basement shelter, her mother said that they had to leave the area immediately or they would not survive. Only five of the eighteen people in their shelter left in time; the others perished. Lydia described what happened next:

The air was hot and thin. We stumbled over a couple of blackened, naked, hairless mannequins lying on the street. Timbers were falling and sparks threatened to ignite hair and clothing, so we wrapped our heads [with wet towels] and ran to the public shelter built into the mountain close by. Only later . . . did we realize that those were not mannequins but people who were not as lucky as we. When we returned the next morning, there was nothing. Not one stone above another. You could barely tell where the house had been. [27]

After her uncle’s home was destroyed, Ruth Bodon went to live with her sister Charlotte, the wife of Kurt Schneider, president of the Strasbourg District. While in Strasbourg, she attended meetings of the branch with her sister’s family. That French city was occupied by the German military, and the members of the small branch spoke both French and German. “We never talked about politics, Hitler, or the war,” Ruth claimed.

Ruth was drafted into the national labor force, or Reichsarbeitsdienst in the fall of 1944 and assigned to a factory in Kirchheim unter Teck, not far from home. She liked the factory work more than farmwork and enjoyed working at a manual knitting machine, making socks for soldiers. When that assignment ended after six months, Ruth thought she would be allowed to go home, but her term of service was not finished. Her next job was very unpleasant: she tested gas masks, putting them under pressure to determine if there were any leaks. “The gas made me deathly ill, but I only did that for a month. One day, our lead girl came in and told us: ‘The war is coming to an end. Go home, but in groups. Don’t go alone.’” Ruth decided to join her sister Charlotte, whose family had left Strasbourg when the American army approached and moved to a little town in the Black Forest.

Esther Ruf recalled that there were not many opportunities to enjoy life as a young teenager during the war: “I had the feeling that I couldn’t really do the things that others my age did. Maybe that was because we weren’t very well off. I could go swimming because there was a pool nearby. I remember reading two books every weekend. That was fun time for me. Every once in a while I could go to a movie, but we didn’t go out that often.”

In late May 1944, Kurt Ruf arrived in France with his tank division. A few days later, the Allies landed on the beaches of Normandy, but Kurt was as yet far from the action. He wrote to his father, Hermann (then the president of the Frankfurt Branch) on June 8 with very bad news:

You have probably heard from Maria or from somebody else that Alma was killed on March 14 at Nikolajew [Russia]. This is a very painful loss, but who knows what will happen to all of us? He has it really good now. He certainly doesn’t want to come back to this world with all of these evil people. I know that he’s in a better place now, and I wish him all the best in heaven. [28]

Fig. 5. Kurt Ruf was a member of the crew of this tank when he was killed in France in August 1944. (L. Ruf Wright)

Fig. 5. Kurt Ruf was a member of the crew of this tank when he was killed in France in August 1944. (L. Ruf Wright)

Fig. 6. Members of the Stuttgart Branch.

Fig. 6. Members of the Stuttgart Branch.

But the action caught up with Kurt, who wrote again to his father on August 6, 1944: “I am writing you a quick note in haste. All of a sudden, I was in combat against the Americans. I’m very well right now. I hope that you’re at least not any worse than before. I send you my best wishes. Your Kurt. Auf Wiedersehen!” [29] Four days later, Kurt was killed in battle.

The birth of a child in wartime Germany was an extraordinary challenge for many women—including Ute Auktor’s mother. Ute was born in a Stuttgart hospital on September 28, 1944, but there was nothing typical about the process. Her mother explained the situation, and Ute related the events as follows:

My mother was taken to the hospital for my birth. (My father was not there; he was out of town with the army.) Just as I was born, the doctor heard the air-raid sirens, which were going off all the time. I was 9½ pounds or something, a good-sized baby. And my mother was just a short lady, 4 foot 11, if she was that tall. They bundled me up, put me into her arms, and told her to go to the nearest air-raid shelter, which was down the street from the hospital, so she had to walk outside. She told me that one of the bombs landed not too far away from the building, and the force of it knocked her to the ground while she was still clutching me. A gentleman came up to her and offered to help. She was holding me so tightly that the poor man thought she was going to suffocate me. He had to finally just lift her up and get her to the air-raid shelter. And that was just about twenty or thirty minutes after I was born. It was kind of a rough entrance into the world. [30]

As a German POW in Alabama during the war, Walter Speidel had a rare treat—a visit from his sister. Elisabeth Speidel had married an American and immigrated to Utah before the war. When the Red Cross informed her of Walter’s presence in Alabama, she requested and received permission to visit him there. According to strict regulations, an officer was assigned to be with the siblings and listen to all that was said. As Walter recalled:

It was a little awkward at first, but Elisabeth handled the situation cleverly, putting the lieutenant at ease. . . .We talked and talked. First, about our parents and [my girlfriend], and Elisabeth’s acquaintances in Stuttgart. . . . The few hours were gone too fast. We met the next one or two days. Towards the end, Elisabeth asked me what I would like her to send me. I told her that we actually had everything we needed. Perhaps, some personal things, church literature, etc. It was very difficult to say good-bye. Afterwards, everything appeared so unreal to me, like a “mirage” that now had all of a sudden disappeared. [31]

Erika Greiner Metzner (born 1919) was expecting her second child in July 1944 when her husband, Heinz, came home one evening with the announcement that she and their son, Rolf Rüdiger (born 1942), needed to leave Stuttgart at once. He helped her pack for the long trip of six hundred miles east to Silesia, where his relatives were surprised to see her but pleased to take them in. As much as she wished to stay with her husband (he was not allowed to leave), she knew that the chances for survival were much greater in the town of Frankenstein. Once there, she found life so peaceful and comfortable that she had “a bit of a guilty conscience.”

Following the destruction of the branch meeting rooms on Hauptstätterstrasse, branch leaders spent a good deal of time seeking a suitable meeting place for this branch, which in the last two years of the war still enjoyed a large local population. An important document found among the papers of the Stuttgart Branch is remarkable:

October 11, 1944 no. A.5303

From the Lutheran Church Council in Grossheppach, Waiblingen County, to the office of the Lutheran Church District of Stuttgart: According to a report from your office, the representative of the Church of Jesus Christ (previously called Mormons) since their meeting hall in Stuttgart was destroyed and they cannot find a place to meet, has petitioned for the use of the hall in the Gaisburg Church each Sunday afternoon beginning at 3:00 p.m. until such time that they can find another place to meet. Although it has always been our practice to support churches that have lost their meeting places, the Lutheran Church District Office should consider declining this request, because allowing churches that are not solidly based on Christianity to meet in our buildings would send the wrong message to members of our church. Because this religious group is so small, it should be possible for them to find another location for their meetings. [32]

This is an important reminder that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was generally not looked upon as a church (Kirche) anywhere in Germany at the time but rather as a sect (Sekte), a word that in the German language did not have a positive connotation.

Millions of German women gave birth during the war to children whose fathers were far from home in the service of their country. Erika Metzner was one of those women, but giving birth in a home or a hospital under planned conditions was one thing—going through the same process while trying to flee the invading Soviet army was quite another, as she recalled:

It took us nearly an entire day to go the first twenty-five miles to Bad Landeck. I was helping to get our baggage off of the train when my water broke. . . . My sister-in-law turned pale when I told her. She ran off to find some assistance, and they found a car to take me to the [women’s hospital]. I was very scared, because I didn’t know what would become of my relatives and my little boy. That very night—February 15, 1945—I gave birth to a healthy little boy [Heinz Peter]. [33]

Sister Metzner stayed in the hospital for ten days and was then sent to a mothers’ home. This might normally have been a very pleasant experience, with mother and baby under the care of a nurse for a few weeks after birth, but it became a tragedy. As that terribly cold winter came to an end, there was no fuel left to heat the building. “Every day they carried out dead babies. They just weren’t used to the cold,” she explained. Her son was only three weeks old when he too passed away on March 10, 1945. A few weeks later, Erika Metzner and two-year-old Rolf Rüdiger boarded a train for home. The Soviet army was approaching, and it seemed that every German civilian in Silesia was determined to flee to the west rather than wait and see what the conquerors would do.

Traveling with Erika Metzner and her son were a sister-in-law and three children. It seemed like a miracle when they found passage together on a train to Vienna, where the tumult at the main station was daunting; again it seemed that everyone was headed west. From Vienna, another train took the six west to Fürstenfeldbrück, a town just outside of Munich. Seemingly stuck there as the war neared a conclusion, Sister Metzner had no way to proceed, but managed to write a letter to her husband back in Stuttgart. After about one week in Fürstenfeldbrück (“where we had a bed and water!” she rejoiced), Erika answered a knock at the door and opened it to see her brother Lothar Greiner. Only sixteen, he had left Stuttgart with the sole purpose of finding his sister and his nephew and taking them home. In Stuttgart, Erika found that her home was still standing. She described her feelings at the time: “I was so pleased to be home again with my dear family. But best of all, my husband showed up just a few weeks later. We were reunited, and what a blessing that was! And I was so happy to attend church again with my branch.”

One day in April 1945, Lydia Ruf heard shooting and looked out the attic window. Seeing tanks rolling across fields in the distance, she hurried downstairs to tell her mother that the Americans were coming; it appeared that they would be in town soon. Regina Ruf quickly issued an order: “Let’s kill the chickens!” The landlady was gone but had given instructions that the chickens in her coop should not fall victim to the invaders. According to Lydia:

Mother went out to kill the chickens, brought them in, and we cooked them, put them in mason jars, and buried them in the garden. The next day the tanks rolled in. There was a little shooting in the streets, so mother and I hung out a white sheet, while our neighbor still displayed his flag with the swastika on it. . . . That same day . . . soldiers were coming through all the backyards looking for things like rabbits, chickens, or food of any kind. We felt so smug, since ours were already buried! I think the inspiration that my mother in many instances had, came from living the gospel. [34]

During his stay in three different POW camps in Alabama and North Carolina from 1943 to 1945, Walter Speidel was kept busy at many simple tasks, but there was also time for entertainment and academic pursuits. Walter busied himself studying the English language and became fairly proficient. At one point, he was given a physical examination, and the German physician determined that he was suffering from what was called Schlatter’s disease. This meant that Walter could be classified as unfit for work, and soon he was put on a ship for transport across the Atlantic Ocean to France. He was fortunate to have the unfit classification because many of the POWs who landed in the French port of LeHavre with him were taken by the French and put to work again; their “release” had been a deception. [35] Walter, on the other hand, proceeded to Marburg, Germany, where American military occupation officials gave him the necessary release papers and paid him $92.75 for the work he had done as a POW. [36]

When the end of the war approached, Ruth Bodon was the guest of the Schneider family in Schönwald, a ski resort town in the Black Forest. She liked the setting, but the entry of French troops in April 1945 was more excitement than she had bargained for. As it turned out, the troops entering the town under the French flag were anything but French. Ruth described the terrifying situation:

I had never seen a Moroccan before. They were on horses and had turbans and big beards. They were awful-looking men, and we saw them through our window. All of a sudden, they came to a stop in the street right in front of our house. Apparently their officers were looking for quarters, and they stayed there for about a half hour. My sister was twenty-four, and I was eighteen. My sister said to her husband, “If they come in here, don’t try to protect me. I don’t want to be a widow, too.” My brother-in-law prayed nonstop while they were outside in the street. He never stopped praying. And then they left. In the next town they raped every woman from thirteen to eighty. That would have been our experience if my brother-in-law had not prayed so hard for us to be safe.

After the arrival of the American army in Stuttgart, Lothar Greiner set off to find and rescue his mother and his sisters Edith and Ruth in the town of Waldenburg. Part of the journey was accomplished with the aid of an old bicycle, and part of it in the company of Polish laborers heading home (“I hoped they wouldn’t speak to me.”). He made it to Waldenburg and was united with his mother and sisters, then successfully escorted them home to Stuttgart. “It was wonderful to be together again,” he explained.

Fig. 7. Little Dieter Kaiser with American soldiers in postwar Stuttgart. The second GI from the left is Alan Fry, who later married Maria Ruf, a daughter of the Stuttgart District president. (D. Kaiser)

Fig. 7. Little Dieter Kaiser with American soldiers in postwar Stuttgart. The second GI from the left is Alan Fry, who later married Maria Ruf, a daughter of the Stuttgart District president. (D. Kaiser)

Some of the first enemy troops to enter Stuttgart were French, as Dieter Kaiser recalled: “They were French colonial troops, Moroccans. We used to bang on the lids of pots to cause distractions when those guys came around.” Dieter was only six years old at the time and could not have known what molestations the soldiers were committing, but he apparently understood that their presence represented a great danger.

Esther Ruf explained that her family was never in danger when the enemy invaded Stuttgart. “We still lived in our home at the end of the war and my father was still employed. [The soldiers] never came into our home to steal our belongings or anything like that. Our home and our neighborhood had not been bombed; we just had some windows broken.” Regarding her reaction to the news that Hitler was dead, she recalled: “I think that I was happy when I heard the news. Everything we had been told about him was a lie. I was glad to be a free person and not to live under a system of lies.”

For the Bodon family in the town of Waldsee, the war ended with the arrival of the French army. Brother Bodon wanted to spare the town any damage from senseless defensive action, so he went out at night to remove antitank barriers. To do so during the day could have meant execution as a traitor and a defeatist. At the same time, other local residents believed in resisting the enemy. Harold Bodon recalled that several Hitler Youth boys were ordered to go to the nearby forest and prepare to fight against the invaders. “Of course the French didn’t know that they were boys, so they started mowing down that forest and killed a lot of the kids.”

Just before the French arrived, Brother Bodon loaded a small Bollerwagen with supplies and walked with his family to a farm just outside town, according to Karl-Heinz: “In our family prayers we had always asked to have the Americans occupy our area, so we were disappointed when the French came first. My dad didn’t know if the enemy would come into Waldsee with guns ablazing or not. We hung out a huge white flag, and nothing happened where we were. But back in Waldsee there was a little damage done.”

When the French army marched into Waldsee, the spectacle was frightening, according to Harold:

The Africans came in on camels. They were the first blacks I’d ever seen [and they wore] turbans. The black men were very scary. They kept holding one hand on the little knives that they had on their belts. They would be walking down the street looking straight ahead, then they would suddenly turn and look at us and pull their knives out. I came close to fainting every time that happened.

With the French conquerors in town, Heinrich Bodon was most concerned for the safety of his wife and his daughter, Rosie. He quickly made a deal with the invaders that the family would cook and wash for them if the family were allowed to stay in their home. When it was all over, the worst losses they suffered were their radio, a camera, and a bicycle (all local families had to surrender such items to the French occupation forces). The Bodons lived in relative peace in Waldsee for seven more years.

Fig. 8. Erna Lang Kaiser (left) of the Stuttgart Branch lost twenty-six close relatives (several of them LDS) during the war. Two of her relatives are shown here: Christian Lang (president of the Darmstadt Branch) and his wife, Anna Loeb Lang. Christian and Anna died in the firebombing of Darmstadt on September 11–12, 1944. (D. Kaiser)

Fig. 8. Erna Lang Kaiser (left) of the Stuttgart Branch lost twenty-six close relatives (several of them LDS) during the war. Two of her relatives are shown here: Christian Lang (president of the Darmstadt Branch) and his wife, Anna Loeb Lang. Christian and Anna died in the firebombing of Darmstadt on September 11–12, 1944. (D. Kaiser)

Dieter Kaiser’s mother did an excellent job in keeping her son fed, clothed, and sheltered while her husband was gone as a soldier. When the war ended, his whereabouts were not known, but eventually she learned that he was in a POW camp in Pennsylvania. She and Dieter were living in what was left of the family’s apartment house. According to young Dieter, “a huge bomb destroyed one-half of the home. We could heat only one room after that, but we stayed in the home.” Sister Kaiser’s losses were much greater than property. No fewer than twenty-six close relatives had been killed in the war, including her parents. Her father, Christian Lang, was the branch president in Darmstadt and perished in his basement in the firebombing of that city on September 11–12, 1944, along with his wife and several other family members.

When Walter Speidel finally arrived home in Stuttgart after an absence of four years, he was surprised at the condition of the city, as he wrote:

The whole area around the Hauptbahnhof all the way up to Wilhelmsbau, actually all of downtown Stuttgart, the whole inner city, was in ruins, just rubble, only some walls still standing here and there. Streetcars didn’t have any glass, except up front, of course. What had been glass before was now boarded up with wood panels. [Arriving at my parents’ apartment house] I woke up [everybody in the building] when I stomped up the stairs with my heavy American boots and my oversized duffle bag. Now, finally I was home. Was I, really? Or did I just dream?

Asked to speak in church on June 8, 1946, Walter mentioned the blessing in which he was promised he would return “without harm to body or spirit.” Those remarks engendered some poor feelings among branch members in attendance. Several wondered why he had been given a special blessing promising his survival when a number of men and boys of the branch had perished in the war. “They were asking, ‘Why didn’t our sons receive that blessing?’ I realized soon that I shouldn’t have mentioned the blessing.” [37]

The Latter-day Saints of the Stuttgart Branch had suffered substantial losses in life and property. Nearly all had lost their homes and were compelled to leave the city for at least a short time. It would be months and even years before some of them could return and join with their friends and family for worship services again.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Stuttgart Branch did not survive World War II:

Georg Andreas Konrad Bibinger b. Frankenthal or Gönkental, Pfalz, Bayern, 18 Apr 1884; son of Georg Bibinger and Anna Elisabeth Neufahrt; bp. 4 Jun 1921; conf. 4 Jun 1921; ord. deacon 29 Oct 1922; ord. teacher 23 Nov 1924; ord. priest 14 Oct 1928; ord. elder 2 Oct 1932; m. 28 Oct 1922, Rosine Fauser (div.); 2m. Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 27 Jul 1931, Maria Luis Klink; d. heart attack Stuttgart, 10 Oct 1943 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 200; FHL microfilm 25723; 1930 census; IGI)

Frida Luise Brosi b. Hohenhaslach, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 24 May 1886; dau. of Gottlieb Brosi and Christina Frank; bp. 20 Jun 1918; conf. 20 Jun 1918; m. 2 Apr 1908, Gottlob Rieger; d. blood and liver poisoning 15 Sep 1939 (Der Stern no. 20, 15 Oct 1939, 323; FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 637; FHL microfilm no. 271403; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Emil Claude b. Donaueschingen, Villingen, Baden, 2 Feb 1871; son of Maria Claude; bp. 9 Aug 1924; conf. 9 Aug 1924; d. cerebral apoplexy 25 Oct 1939 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 46; FHL microfilm 25741; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Dieter Werner Fauser b. Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 9 Sep 1935; son of Wilhelm Werner Fauser and Maria Barbara Katharina Soravia; d. diphtheria 15 May 1942 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 633; FHL microfilm 25765; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Maria Theresia Gommel b. Mengen, Donaukreis, Württemberg, 26 Sep 1875; dau. of Johannes Gommel and Pauline Schuhmacher; bp. 25 Jun 1911; conf. 25 Jun 1911; widow; d. dropsy 20 Dec 1944 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 305; FHL microfilm 25775; IGI)

Johannes Albert Heil b. Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 6 Sep 1912; son of Johann Wilhelm Heil and Friedrike L. Hohlweg or Hohlweger; bp. 17 May 1924; conf. 17 May 1924; k. in battle Italy 17 Sep 1943; bur. Cassino, Italy (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 544–45; FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 974; FHL microfilm 162780; 1935 census; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Otto Friedrich Hertfelder b. Feuerbach, Württemberg, 8 Aug 1900; son of Ludwig Hertfelder and Berta Löffler; bp. 30 Apr 1921; conf. 30 Apr 1921; missing as of 20 Nov 1945 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 314; FHL microfilm 162782; 1935 census)

Elise Anna Keller b. Buch, Frauenfeld, Thurgau, Switzerland, 28 Dec 1861; dau. of Johannes Keller and Barbara Leumann; bp. 21 May 1914; conf. 21 May 1914; m. Ossweil, Ludwigsburg, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 26 Oct 1884, Johann Friedrich Kahl; 6 children; d. senility Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 23 Mar 1940 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 280; FHL microfilm 271376; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Regine Karoline Klink b. Alfdorf, Welzheim, Jagstkreis, Württemberg, 17 Dec 1873; dau. of Matthaeus Klink and Katharina Mueller; bp. 15 Apr 1922; conf. 15 Apr 1922; m. —— Loos; d. lung ailment 13 Dec 1944 (CR 375 8 2451, no. 379; FHL microfilm 271388; 1935 census; IGI)

Max Franz Knecht b. Schwäbisch Gmünd, Württemberg, 19 Feb 1910; son of Gottlieb Knecht and Christina Joos; ord. priest 1935; k. in battle. (M. Ruf Fry; FHL microfilm 271380; 1925 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Christine Kurz b. Gniebel, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 24 May 1865; dau. of Christian Kurz and Rosine Barbara Schäfer; bp. 4 Dec 1918; conf. 8 Dec 1918; m. Gniebel, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 28 Nov 1895, Jakob Scholl; d. cerebral apoplexy Stuttgart, Württemberg, 27 Aug 1941 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 541; FHL microfilm 245258, 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI; AF)

Karoline Friedrike Lombacher b. Marbach or Steinheim, Neckarkreis, Württemberg 20 Dec 1864; dau. of Thomas Lombacher and Friederike Märtzirer or Märtyrer; bp. 9 Aug 1924; conf. 9 Aug 1924; m. 28 Sep 1889, Johann Friedrich Osswald; d. old age 24 Mar 1945 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 42; IGI)

Horst Walter Lutz b. Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 10 May 1924; son of Karl Wilhelm Lutz and Elisabeth Lutz; bp. 29 Mar 1935; conf. 29 Mar 1935; k. in battle Neustadt/

Pauline Auguste Neugebauer b. Schweidnitz, Schlesien, 27 Apr 1866; dau. of Pauline Neugebauer; bp. 18 Sep 1926; conf. 18 Sep 1926; m. —— Reicheneker; d. old age 29 Sep 1942 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 201; FHL microfilm 271400; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Hildegard Rieger b. Fellbach, Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg 6 Sep 1908; dau. of Gottlob Rieger and Luise Frida Brosi; bp. 24 May 1932; conf. 24 May 1932; m. Stuttgart, 18 Jun 1932, Willy Fritz; d. meningitis Stuttgart, 21 May 1943 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 539; FHL microfilm 25770; IGI)

Alma Helmuth Erwin Ruf b. Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 22 Nov 1920; son of Hermann Otto Ruf and Regina Honold; bp. Stuttgart 30 Jun 1929; conf. 20 Jun 1929; ord. deacon 4 Oct 1934; ord. teacher 3 Dec 1939; ord. priest 29 Dec. 1940; radioman; k. in battle by Oktabriske sixty km east of Nikolajew, Russia, 14 Mar 1944 (L. Ruf-Wright; CHL CR 375 8 2451, no. 642; FHL microfilm 271407; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Fig. 9. Brothers Kurt and Alma Ruf were both killed in battle in 1944. (L. Ruf Wright)

Fig. 9. Brothers Kurt and Alma Ruf were both killed in battle in 1944. (L. Ruf Wright)

Kurt Walter Ruf b. Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 10 May 1923; son of Hermann Otto Ruf and Regina Honold; bp. 30 May 1931 Stuttgart; conf. 30 May 1931; ord. deacon 22 May 1938; Waffen-SS lance corporal; tank crew; Iron Cross Second Class; k. in battle Noans or Alenson, France, 12 Aug 1944 (L. Ruf-Wright; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, district list 218–19, district list 1947, 544–45; FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 818; FHL microfilm 271407; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI; AF)

Werner Hermann Widmar b. Stuttgart-Untertürkheim, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 3 May 1921; son of Friedrich Widmar and Luise Frieda Rüdle; bp. 19 Jul 1930; conf. 19 Jul 1930; ord. deacon 4 Aug 1935; rifleman; k. in battle Naljiwajka (near present-day Trojanka Naljiwjka, Uman, Ukraine) 6 Aug 1941 (L. Ruf-Wright; www.volksbund.de; CHL CR 375 8 2451, no. 451; FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 451; IGI)

Notes

[1] Stuttgart city archive.

[2] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CR 4 12.

[3] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[4] Erwin Ruf, “Denkschrift zur Feier des 40 jährigen Bestehens unsrer lieben Stuttgarter Gemeinde” (unpublished); private collection; trans. the author.

[5] Walter Speidel, interview by the author, Provo, UT, February 23, 2007.

[6] The other two branches were Hamburg-St. Georg and Essen.

[7] Ruth Bodon Andersen, telephone interview with the author, August 13, 2009.

[8] Esther Ruf Robinson, telephone interview with the author, April 13, 2009.

[9] Dieter Kaiser, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, March 5, 2006.

[10] Lydia Ruf Wright, “There Will Always Be Lilacs in August” (unpublished, 1992), 10; private collection.

[11] Ruf, “Denkschrift.”

[12] Maria Ruf Fry, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann, December 8, 2008.

[13] Walter Speidel, “Lebendig Gewordenes Gedächtnis” (unpublished), 123; private collection. The name of the young woman is withheld by request.

[14] Lothar Greiner, interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, Markgröningen, Germany, August 17, 2006, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[15] Stuttgart District records, 175, CHL MS 13360; trans. the author.

[16] Ibid., 177.

[17] Walter told a humorous story involving his father after the reunion in 1946: “My father told me he had seen a newsreel in the theater showing that it was so hot in Africa that German soldiers could cook an egg on the armor of a tank. I told my dad that the scene was only a trick, that there was actually a soldier underneath the tank with a blow torch to heat up the metal. My dad insisted that it was true because he had seen it on an official government newsreel. I had a hard time convincing him that it was all a ruse, a joke.”

[18] Speidel, “Lebendig,” 153.

[19] Wright, “Lilacs,” 10.

[20] Speidel, interview.

[21] Karl-Heinz Bodon, telephone interview with the author, July 22, 2009.

[22] Speidel, “Lebendig,” 184–88.

[23] Kurt Ruf, diary, July 6, 1943; used with permission of Lydia Ruf Wright.

[24] Wright, “Lilacs,” 11.

[25] Wright, “Lilacs,” 10.

[26] Kurt Schneider (the husband of Harold’s half-sister Charlotte) was the district president in Strasbourg, France, at the time. He enjoyed the use of a company car and traveled extensively in southwest Germany for church purposes.

[27] Wright, “Lilacs,” 11–12.

[28] Kurt Ruf to Hermann Otto Ruf, June 8, 1944; used with permission of Lydia Ruf Wright.

[29] Kurt Ruf to Hermann Otto Ruf, August 6, 1944; used with permission of Lydia Ruf Wright.

[30] Ursula Auktor Augat, interview with the author, Salt Lake City, December 1, 2006.

[31] Speidel, “Lebendig,” 191. Walter’s copy of the Book of Mormon had been taken by French guards when he was captured.

[32] Stuttgart District records, 176.

[33] Erika Metzner, “A Report of My Flight in the War Year of 1945 from Silesia to Stuttgart,” (unpublished, 1981); used with permission of Rolf Rüdiger Metzner.

[34] Wright, “Lilacs,” 12–13.

[35] Many thousands of German POWs (including several LDS men) were released by the Americans and British under the ruse of being sent home, only to be transferred to other POW camps in Belgium and France, where they stayed another year or more.

[36] Speidel, “Lebendig,” 199.

[37] Speidel, interview.