Strasbourg Branch

Roger P. Minert, “Strasbourg Branch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 403–408.

Strasbourg, the capital city of the historic province of Alsace-Lorraine, had been a cultural center for centuries. When Kurt and Charlotte Schneider moved from Stuttgart, Germany, to Strasbourg, France, in 1940, the city had just been conquered as a result of the war. “My husband worked for a metal products company, Thyssen Rheinstahlwerke. He was the director of the new Strasbourg division of the company. They made pots and pans out of aluminum.” [1] They were married just weeks after the war began and were looking forward to a happy life together.

The move to Strasbourg as the new director may not have taken place had Kurt not suffered a small accident in Stuttgart just after the war began. In the dark of the blackout, a German soldier running down the street hit Kurt and broke his ankle. When informed of the accident, Charlotte expressed delight rather than sorrow. She realized that the accident might well delay or prevent Kurt’s call to the Wehrmacht. Indeed, his promotion to director soon came through, and his war-critical employment exempted him from military service during the entire war. [2]

There had apparently been a small group of Latter-day Saints in the city for several years, and the Schneiders lost no time in seeking them out. Over the next four years, the diary of Charlotte Schneider includes hundreds of entries featuring the branch. The following names are prominent: the Georg Müller family, Sister Feister, the Kaiser family, the Hechleiter family, Sister Staperfend, and Brother Renk. [3] As she recalled, “The Saints spoke German but nearly everybody could speak French also. We met in rented rooms.”

Fig. 1. Members of the Strasbourg Branch gathered for this photograph in 1941. It appears that the branch was renting rooms in a nice downtown neighborhood at the time. Charlotte and Kurt Schneider are at the far left. (C. Bodon Schneider)

Fig. 1. Members of the Strasbourg Branch gathered for this photograph in 1941. It appears that the branch was renting rooms in a nice downtown neighborhood at the time. Charlotte and Kurt Schneider are at the far left. (C. Bodon Schneider)

“We had such a beautiful apartment in Strasbourg,” recalled Charlotte Schneider. Indeed, Kurt’s company put the couple up in a fine apartment near the downtown area. This setting is consistent with his position as director in a large corporation. Charlotte (called “Lotte” by her family and friends) soon fell in love with that beautiful old city, and her diary reflects the attachment: they attended the theater and the cinema and became acquainted with the city’s beautiful parks.

Kurt Schneider apparently became the leader of the Strasbourg Branch soon after his arrival, but the exact date of the call cannot be determined. Nothing is said about this in the mission records, and the branch records did not survive the war. However, Charlotte’s diary includes many references to leadership functions, and the fact that Kurt was allowed to use his company automobile for church activities likely made him the primary traveler among the Saints on the west side of the Rhine.

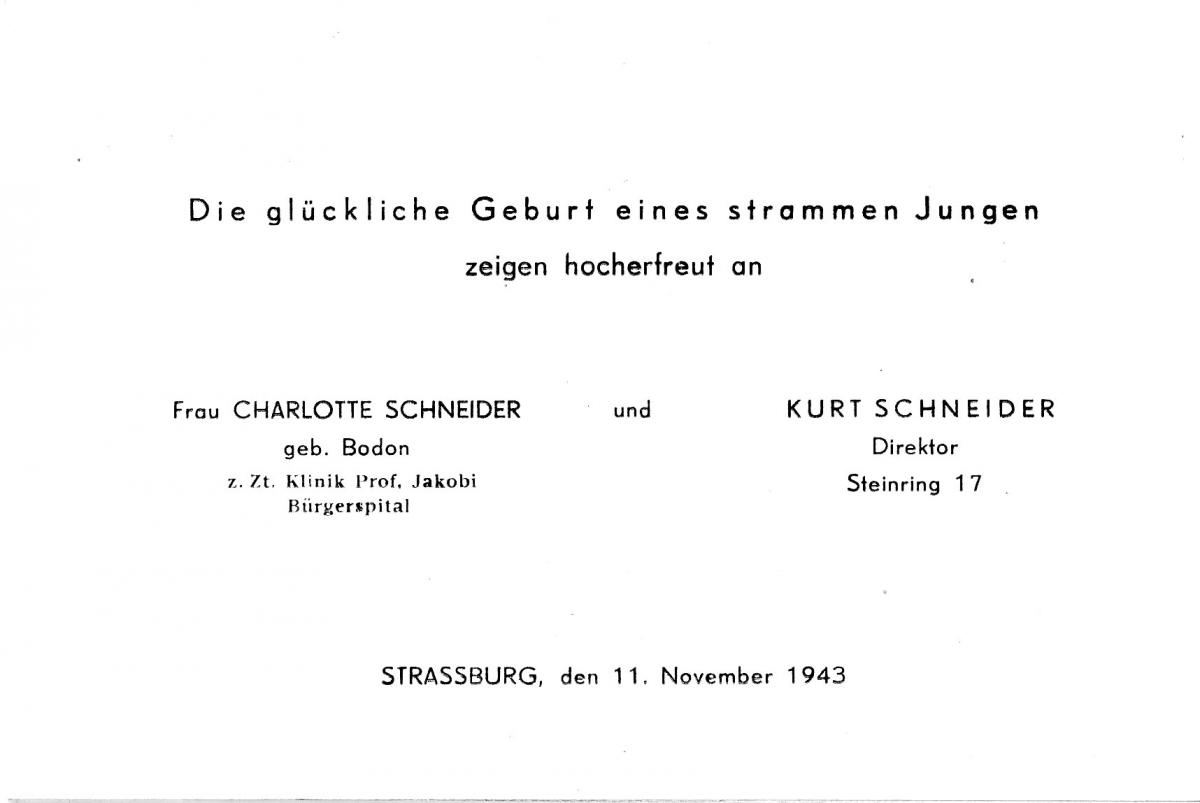

The Schneiders became parents in November 1943 with the birth of their son Werner. As befitted an upper-class family of the era, they sent out a formal announcement beginning with the line, “We are thrilled to announce the birth of a strapping little boy.”

Fig. 2. The Schneiders announced the arrival of their first child with this card. (C. Bodon Schneider)

Fig. 2. The Schneiders announced the arrival of their first child with this card. (C. Bodon Schneider)

That the Strasbourg Branch was still in its infancy in early 1944 is clear from the diary entries of Sister Schneider. The entry dated February 14 reads, “Founded the Relief Society today; the leaders are [Sisters] Abogast, Grob and Kaiser.” [4] Discussions on the founding of that society in the Strasbourg Branch had begun earlier that year. There is no indication of when the meetings were held nor how many sisters attended. From various entries in the diary, we learn that Sunday School was held in the morning and sacrament meeting at 3:00 p.m. Primary meetings were held on Mondays.

Some entries from Charlotte’s diary from 1944 are indicative of the ongoing activities of the branch and the family during a time when it was becoming increasingly clear that Hitler’s armed forces were not sufficient to contend against enemies on several fronts. Her diary comment of June 6 (D-Day) is interesting: “Great excitement! The Allies have succeeded in their invasion.” [5] She shared the excitement of the people of Strasbourg, who were waiting to be liberated after years of life under German occupation.

During the spring and early summer of 1944, little Werner Schneider became seriously ill and was hospitalized for weeks. In those days, parents were not allowed to stay with children in the hospital, and Charlotte’s diary entries reflect her agony at having to leave the boy among strangers. His condition did not improve completely during the next year and was a constant subject in his mother’s diaries. [6]

The branch still had nice rooms to meet in, as is apparent from Charlotte’s diary entry dated Friday, August 11: “The fifteenth [air raid] today. The city center was hit. I took Werner to the doctor. The windows in our branch rooms were broken.” [7]

In August 1944, the American army was approaching Strasbourg, bent on liberating the provinces of Alsace-Lorraine from their status as occupied territory. Kurt Schneider’s company was soon forced to curtail operations in its facilities in and around Strasbourg. The family would have to give up the luxurious apartment in the city they had grown to love during the previous four years. Charlotte Schneider made several diary entries from August 15 to 25 expressing the difficulty of packing up their belongings in preparation for the move (as many other German citizens in Alsace-Lorraine at the time were doing).

Fig.3. The bedroom of the Schneiders’ apartment in Strasbourg. (C. Bodon Schneider)

Fig.3. The bedroom of the Schneiders’ apartment in Strasbourg. (C. Bodon Schneider)

As sad as the Schneiders were to leave Strasbourg, Charlotte’s diary reflects their happiness in Schönwald, a very small town far from the war. However, she was aware that the war was nearing its end and the future was uncertain when she wrote this entry on September 5: “Great weather but a bit stormy. Had my hair done, and then sat out in the sun behind the house this afternoon. I am very worried about the future. We hear that there is already fighting in Saarbrücken.” Her entry the next day was comforting: “I read all day long. We can survive up here [in Schönwald].” Back in Strasbourg, conditions for the remaining Saints were deteriorating. A terrible attack against that city took place on September 25, but a Brother Eyer called the Schneiders to report that the branch members were spared. [8]

Elfriede Recksiek (born 1925) of the Bielefeld Branch had been living with the Schneider family for some time as a domestic servant. She decided to return to her parents in Bielefeld for the Christmas season and departed Strasbourg on December 24. [9] Charlotte wrote the following in her diary: “This morning Elfriede left for Bielefeld. I cooked a pork schnitzel. After our dinner I sat in the sun with Kurt behind the bath house. This evening we celebrated Christmas Eve with the Dold family. Werner saw the Christmas tree. We exchanged small gifts and played games until 11 [p.m.].” [10] Elfriede returned to Schönwald on January 2, 1945, to resume her duties in the Schneider household, but she left for good at the end of the month. She was fortunate to be at home in Bielefeld before the American army arrived there in March.

Life in the beautiful Black Forest would have been more pleasant for Charlotte during the winter months of January and February 1945, but Kurt was hospitalized, and their son, Werner, then fifteen months old, was constantly ill. Several times, Sister Schneider had to carry the little boy through the snow to the hospital in Triberg for treatments and shots. Amid the health trials, she was also asking herself serious questions about the German leaders. The following diary entries reflect this:

Saturday, February 24: I heard Hitler speak today [on the radio]. He prophesied a German victory this year and said that history will take a turn for the better.

Wednesday, February 28: [propaganda minister Josef] Goebbels spoke on the radio: we have to do more with less. There will be no new weapons.

Tuesday, March 20: I am really unhappy about the current political situation. What the [German] people have to go through now is terrible! [11]

By mid-April 1945, life in little Schönwald was becoming chaotic for the Schneider family. German troops were moving through town, retreating from the approaching French. Russian and Polish POWs were being moved out of the area. French artillery and German antiaircraft fire were making it too dangerous to be outside, and the Schneiders spent much of the time huddled in their basement. Military vehicles were moving through the streets in every direction. On Sunday, April 22, Charlotte wrote, “We got up early. Great excitement. We are surrounded. The traffic has come to a stop on the roads. We heard shooting and Kurt saw two vehicles that looked like tanks.” [12] The French troops had conquered the area around Schönwald and were moving farther north and east.

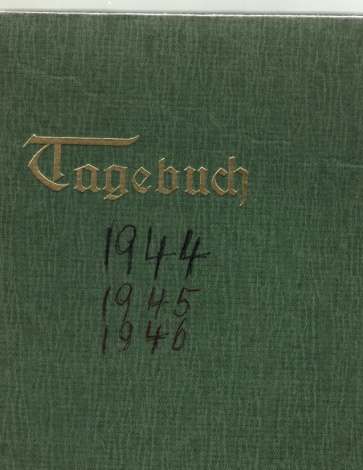

Fig. 4. The cover of Charlotte Bodon Schneider’s second diary. (C. Bodon Schneider)

Fig. 4. The cover of Charlotte Bodon Schneider’s second diary. (C. Bodon Schneider)

With the fighting over and the war only a few days from its official conclusion, Kurt Schneider likely thought that the family’s greatest troubles were behind them. However, this was not to be the case under the French military occupation forces, as the Schneiders learned firsthand. The events of the next sixteen days were recorded in great detail in a new post office savings account book Kurt somehow acquired. With paper almost impossible to come by at the time, Brother Schneider was fortunate to have anything to write on. The following are excerpts from that diary: [13]

Wednesday, May 2: Arrested at 9:30 a.m. in front of my house. I didn’t know that there was a curfew. We stood around in the snow in front of the church until 10:30. We were searched for weapons twice and they checked our papers. Then they took me and four others to the city hall. We were allowed to have somebody bring us something to eat. Searched again for weapons and papers at [4:30 p.m.], then loaded into a truck. The major (a coward!) didn’t do anything to help us. Somebody told Lotte what was happening and she came by just in time. I gave her some money and kept 65 Marks for myself. They drove us through Furtwangen to Villingen. During the trip each of us was given two crackers. The only thing we were allowed to keep were our personal ID and our wedding rings.

Friday, May 4: [Terrible sleeping conditions] Very concerned and sad.

Saturday, May 5: A very pleasant period began in the camp.

Sunday, May 6: They marched us on foot to Rottweil (13 miles). We had hardly anything to eat: 8 pieces of bread, margarine. Three rest stops. In Rottweil the civilians were separated [from the soldiers] and released immediately. They were loaded into trucks. Then they drove us back to Schwenningen and put us into the Gestapo prison. The cells were in the basement. . . . I tried to stay happy by thinking about being released.

Tuesday, May 8: Read a novel by Dora Holderich.

Saturday, May 12: My stomach couldn’t tolerate a piece of bacon. I’m not accustomed to such food any more. . . . There is nobody here to represent us [in getting out]. . . . Spent an hour in the yard this afternoon. Had a conversation with a comrade about the gospel—a long, intense conversation.

Sunday, May 13: Very bad night. Hardly got any sleep. The snoring was intolerable. . . . Very worried about my family. In general very depressed. . . . Studied French this evening. Read a novel.

Monday, May 14: Wrote cards to inform Lotte of my status (to be passed along from person to person).

Wednesday, May 16: Had a very long discussion in our room about the gospel. I bore a powerful testimony. H. Warner had become acquainted with the Church in Zürich [Switzerland]. Hogwash! The usual stupid rumors. I was able to dispel them. About 10–12 persons in attendance.

Thursday, May 17: It is so sad to see how the people stand around waiting for a bite to eat. Like a zoo. It is shameful that when some food is brought around, they won’t share with others. . . . Another interrogation: occupation, party affiliation, family status, what I plan to do now [for work]. Still very intense and exact. It’s hard to remain positive. Finally I was released. . . . I preached the gospel to two comrades.

One day, Kurt and several other prisoners were loaded onto a train to be sent to France. He knew that such a move might mean that he would never return. Agonizing about how to escape despite the many guards surrounding the prisoners, he suddenly recalled two verses from the Bible: Joshua 1:9 and John 14:27. He knew what to do and recalled the situation in these words:

The spirit commanded me to jump from the car. It was as if I were pushed by a higher power. Soldiers with machine guns came running from all directions. I stood straight and unafraid. Then I pushed them away. They lowered their guns, which had been pointed at me. My actions stupefied those grim-looking soldiers. The looks on their faces indicated fear and respect. I spoke English to them, I don’t know where it came from: “I am in the service of America. I am on an important mission.” One of the officers understood my English and called the station commander. I told him my story in a more forceful manner, with strong body language. He released me! Then I was escorted into the town where the French captain in charge was stationed. I related my story to him and I was set free immediately. [14]

The rest of the adventure is told in his diary:

Friday, May 18: [On the way home] I wasn’t used to walking so far anymore and my body was weakened. The sight of us caused quite a stir in the village. Mrs. Dold was in her garden and nearly stared herself blind when she saw us. . . . Lotte and Ruth were beside themselves with joy. Sometimes I can’t believe it myself—that I’m free and my trials are over.

During Kurt’s absence, Charlotte Schneider had been in perhaps a worse situation. With French soldiers on the prowl for loot and female victims, she had to hide herself while caring for two little boys. Even such simple tasks as hauling water from a local well could be very dangerous to her at the time. Watching her husband be arrested and taken away for no apparent reason was painful to this young wife. She made the following entries in her diary during his absence: [15]

Wednesday, May 2: Very unlucky day. Kurt went to the tailor. While he was gone an order was issued regarding curfew. On the way home he was caught by three French soldiers and hauled away. They first put him in the church and then in the city hall. Then they put him on a truck with three other men to be taken away. Where to? I saw him as they drove away and he was very discouraged.

Thursday, May 3: Kurt is still gone. I think he is in Villingen. I fasted for him this evening.

Friday, May 4: Kurt is still gone. I went to the city hall to ask where he is.

Sunday, May 6: We heard today that there is a cease-fire [the war is over].

Sunday, May 7: I asked Mr. Scherzinger if he would walk to Villingen with me [to search for Kurt] but he said no.

Tuesday, May 8: Mr. Brucker came back from Villingen and said that Kurt is not there.

Tuesday, May 15: I spoke with the [French] commandant and gave him a letter for Villingen. He will try to forward it.

Friday, May 18: Kurt came back from his imprisonment at 7 p.m. He is in very good spirits and even took a bath. He talked about [his experiences] until midnight.

It can hardly come as a surprise that Sister Schneider was unable to find somebody who could penetrate the French POW system to rescue her husband. In the confusion that reigned during the last days of the war and the ensuing fragile peace, soldiers and civilians alike were incarcerated and interrogated by the invaders. Kurt Schneider was not a soldier, but as a member of the National Socialist Party he was automatically suspected of contributing to the misdeeds of the fatherland.

On July 23, 1945, Charlotte Schneider was walking to Triberg. Instead of taking the main road, she chose to walk a small path by some waterfalls. It was there that she was attacked by a Moroccan soldier. “I had seen dark-skinned people before, so I was not particularly scared. . . . [but this time] I was attacked by a Moroccan. I was scared to death and screamed for help.” Fortunately, somebody came by in time to intervene on her behalf.

The Strasbourg Branch had never been particularly strong during the war, but in May 1945 the branch president was miles away in Germany, and the prospects of a return to Strasbourg (since returned to France) were bleak. As of this writing, there is no information regarding the members of this branch in the early postwar years.

No members of the Strasbourg (France) Branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are known to have lost their lives in World War II.

Notes

[1] Charlotte Bodon Schneider, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, June 25, 2009.

[2] Kurt Schneider, Imagining Success (Salt Lake City: Schneider, 1977), 130.

[3] Charlotte Bodon Schneider, diary (unpublished); used with permission.

[4] Charlotte Bodon Schneider, diary.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Elfriede Recksiek Doermann, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, May 4, 2009.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Kurt Schneider, diary (unpublished); used with the kind permission of Charlotte Bodon Schneider.

[14] Schneider, Imagining Success, 140.

[15] Charlotte Bodon Schneider, diary.