Stade Branch

Roger P. Minert, “ Stade Branch, Hamburg District,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 185–90.

Situated in the flatlands about two miles west of the Elbe River, Stade was a city of 88,548 when World War II approached. [1] Ten miles from the huge port of Hamburg, the city was home to a very small branch of Latter-day Saints, not even twenty people. With so few members of the Church in Stade, the list of branch leaders is far from complete. Prominent family names were Gellersen, Tiedemann, and Peters.

| Stade Branch [2] | 1939 |

| Elders | 4 |

| Priests | 0 |

| Teachers | 1 |

| Deacons | 1 |

| Other Adult Males | 2 |

| Adult Females | 8 |

| Male Children | 2 |

| Female Children | 0 |

| Total | 18 |

Louis Gellersen, the owner of a gas station and bicycle shop, was the branch president and was assisted by Christian Tiedemann and Willy Peters. The branch held its meetings in rented rooms on the main floor of a building at Grosse Schmiedestrasse 4. Sunday School took place at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting at 12:30 p.m. There was no official Primary or Relief Society at the time, but members met for Mutual every third Thursday of the month, and a genealogy class was held every fourth Thursday, both at 8:00 p.m. One rare characteristic of the Stade Branch was that the president could be reached by telephone at Stade 2664. [3]

Fig. 1. Members of the Stade Branch in about 1933. (I. Gellersen Long)

Fig. 1. Members of the Stade Branch in about 1933. (I. Gellersen Long)

Even before it began on September 1, 1939, the war had ill effects on the Stade Branch. We read the following in the branch history:

From August 23 to September 16 [1939] we did not hold any meetings due to the political conditions among Germany, Poland and England. The priesthood holders had responsibilities to the people and the [government], so the meetings had to be cancelled. In addition, no evening meetings could be held because of the blackout regulations. [4]

Young Inge Gellersen (born 1928) recalled her experience with the Jungvolk program and national politics in school:

When I was ten years old, I was inducted into the Jungmädel, but my father didn’t let me go. I think I went twice with a friend, but I didn’t like it. They held the meetings in a school; we sang songs, and even the national anthem. We sang the anthem every morning in school, our hands up [in the Hitler salute]. My father never bought me a uniform for the Jungmädel. . . . If you don’t have a uniform, you don’t want to be in a group when everybody else is wearing one. [5]

Inge recalled the meeting rooms: “The Stade Branch met in one large room and a smaller room. They were separated by a curtain. The children had their own section. . . . There was a sign in the window that said that those were the rooms of the Church. It also stated the meeting schedule and times.” Her memories also reflected the vast difference between the LDS setting and the local Lutheran Church: “My mother invited everybody to Church if they seemed interested. One day, she invited a boyfriend of mine. I thought I would die!” Inge’s elder brother Manfred (born 1922) recalled their mother’s missionary spirit: “She was a kind of district missionary. She went around the whole city twice inviting people to come to church.” [6]

Inge also recalled politics in the branch rooms:

There were pictures on the wall in our room. . . . Next to our Joseph Smith picture was one of Hitler. One day, some [government] officials sat in to listen to testimony meeting. Everybody got up and bore their testimony—even me, as a child. The first person to get up was Brother Tiedemann, and he bore a strong testimony and even said something nice about the Nazis—how well they treated us Mormons. . . . Before they left, they clicked their heels and said, “Heil Hitler!” They told us to be careful what we said and did, but after that meeting they left us alone.

The branch history gives insight into the affairs of this small group of Saints. For example, the clerk noted, “No meetings were held from January 7, 1940, to February 25, 1940, because of the terribly cold temperatures.” On April 28, 1940, meetings were canceled due to illness (the same was the case on three other Sundays from 1939 to June 1941 for various reasons and on Sundays when district conferences were held in Hamburg). By June 1941, the attendance had already dropped to about half. [7] This means that only a handful of members were still gathering to worship together by the time the war was halfway over.

According to Inge Gellersen, Willy Peters had made nice benches for the meeting rooms, but during the war he asked to be released as the second counselor in the branch presidency so that he would be able to attend meetings of the Nazi Party. Sister Peters continued to attend church meetings faithfully.

The Gellersen home at Freiburgerstrasse 54 was located next to and behind the bike shop. At some point during the war, the government took Brother Gellersen’s new bicycles; after that, his only business was the repair of older models. His gas station also closed down.

The Gellersen family walked about half an hour to church downtown. Manfred recalled, “We made the trip there and back twice each Sunday. At times the wind blew so hard that we had to walk backwards against it.” During the week, Sister Gellersen cleaned the church rooms and also provided wood and coal from the family supply to heat the rooms on Sunday. As Inge recalled, “She didn’t want to take the wood and coal there on Sunday because she might get her clothes dirty on the way.” According to Manfred, his mother was once cleaning the rooms when some men came in and offered her a job cleaning other rooms in the building. Her response was, “I’m Frau Gellersen. We run a service station, so I don’t need a job. This is my church, and I’m doing this for free.” Sister Gellersen also put up exhibits in the front window on such themes as the Word of Wisdom, the Book of Mormon, and baptism for the dead. Manfred recalled, “My brother had to paint all of the posters for those exhibits.”

Fig. 2. Baptisms in the Stade Branch were conducted in this small canal just north of town. (I. Gellersen Long)

Fig. 2. Baptisms in the Stade Branch were conducted in this small canal just north of town. (I. Gellersen Long)

A trained automobile mechanic, Manfred Gellersen told his father one day that he was thinking of volunteering for the army. His father’s response left a distinct impression: “You don’t volunteer. You wait until you’re called. I’ve been there! I know!” Louis Gellersen had taken part in Germany’s losing effort in World War I. When Hitler ordered the attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, Brother Gellersen informed his son, “The war is lost!” In September, Manfred’s draft notice arrived. He reported to work the next day in his Sunday suit to announce that he was quitting in order to answer the call to the Wehrmacht, although he had no other option.

Manfred was assigned to a duty that reflected his occupational training. “If you can service automobiles, you can service tanks,” he was told. By April 1942, he was in the Soviet Union. He recalled, “I got tired of fixing tanks at 75 degrees below zero.” (Temperatures actually reached only about 40 below.) Fortunately, his observance of the LDS health standards rescued him from such duties. Of the 150 men in his company, he was the only one who did not drink alcohol, but he ended up mixing huge batches of brew for his comrades with hot water, rum, and sugar. One night, an officer angry with his drunk driver got Manfred out of bed to drive for him because Manfred was the only one not drunk. “I ended up doing that the whole time,” explained Manfred.

In the fall of 1942, Manfred was assigned to Armored Assault Regiment 203, working with the Mark III tank. His unit moved within thirty miles of Moscow before the vehicles froze up in the extreme cold. “We would have won the war [against the Soviet Union] if we’d reached Moscow, but the good Lord interferes with guys like Hitler. We were stuck in the mud, and then it froze, and we had to abandon all of our stuff. (Oil doesn’t freeze, it just gets thick like fat.) Then we moved south, and they gave us all new equipment.” Manfred’s unit was sent toward Stalingrad, where they were to help rescue the encircled German Sixth Army. “But the Romanians and Italians didn’t fight, so we couldn’t help [our German comrades]. We had to move back from Stalingrad, so they shipped my unit back to Germany.” [8]

On one occasion, Manfred narrowly avoided being killed or captured by the Soviets. He and a comrade were sent to pick up a load of ammunition and accidentally drove their small vehicle into the midst of fifteen enemy soldiers at an intersection. Reacting with lightning speed, Manfred made a hard right turn and drove past a house, crashing into a fence. His friend was thrown from the vehicle, and Manfred jumped out and ran for cover while fifteen Soviet soldiers fired their machine guns. They missed, but Manfred encountered one more soldier behind the house. Both instinctively bolted in opposite directions, and Manfred was free to make his way back to the German position, ashamed at having left his comrade behind, along with his commander’s suitcase, maps, and other property. Fortunately, when he arrived at his headquarters, his abandoned comrade was already there, safe and sound.

The people of Stade were very fortunate that the city was not the home to critical war industry. Aside from watching and hearing enemy aircraft fly over on their way to Hamburg and other major cities, the residents of Stade went on with their affairs as best they could. The few Latter-day Saints there were sufficiently well off that they were able to respond quickly when the following appeal arrived from the mission office in Frankfurt:

According to general newsletter no. 2 of the West German Mission dated June 27, 1943, as well as by the request of the Hamburg District Presidency, a request is being made of all members to voluntarily donate anything they can—be it money, clothing or other items—for the relief of the members of the Ruhr District, especially the branches in Barmen and Elberfeld, who have lost their homes in recent air raids. The following items were then collected and prepared for shipment to the district leaders in Hamburg:

Brother Louis Gellermann 200 Marks

Brother Christian Tiedemann 20 Marks

Emma Hagenah 5 Marks (nonmember friend)

225 Marks total

The following items were donated by Sister Helene Gellersen of Stade:

[coats, underwear, sweaters, pants, blankets, jackets, pens, paper, cutlery, soap, cups, etc.]

Stade on July 9, 1943 Louis Gellersen, branch president [9]

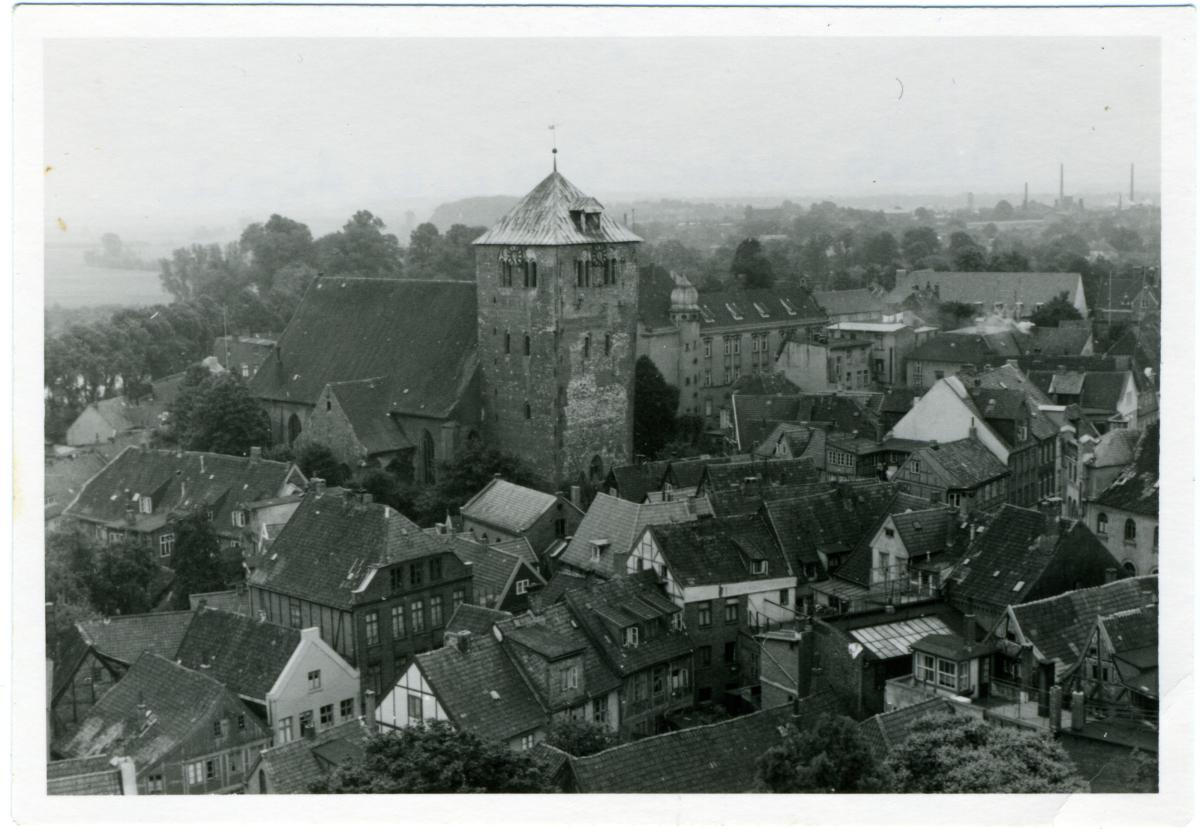

Fig. 3. A very old view of the city of Stade. (I. Gellersen Long)

Fig. 3. A very old view of the city of Stade. (I. Gellersen Long)

Like most teenage girls in the Third Reich, Inge Gellersen was called upon to serve for one year in the Pflichtjahr program. She described the experience in these words:

When I was thirteen years old, I had to serve a Pflichtjahr. I went to a farm in Depenbeck, and when I saw the house for the first time I realized that it must be a huge farm. They had cows and a big and beautiful apple orchard. There were a French POW and a Belgian POW, a Russian forced laborer and a Polish girl named Helena. I got up early every morning before the “madame,” as the French and Belgian soldiers called her. . . . The madame cooked the dinner, but my task was to prepare breakfast for everybody. I worked mostly in the house, but sometimes they would send me outside to help with the hay. The lady was required to give her workers food for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Sometimes it wasn’t very much. She also sent me into town with the ration coupons and told me what to get.

The madame allowed Inge to go home every other Sunday, and she rode her bicycle the ten miles each way. On one occasion, an overzealous policeman stopped her on the road because she was using her headlight after dark. He chastised her for this violation of the blackout laws, insisting that she could be attacked by an enemy airplane. He then fined her 25 Marks, but she earned only 20 Marks every two weeks and did not have that much money with her. The policeman dutifully came to her home to collect the money and recommended that she make her bicycle trips in daylight.

One of the dangers of life in Hitler’s Germany was the possibility of making an innocent statement in the presence of a fanatical party member. Inge recalled how this happened to her mother:

One day a man came to pick up his bike. My mother gave it to him and then looked up to the sky and said, “Oh, we have a blue sky again! Why are we still fighting in this war?”. . . She meant that [the enemy] would come and bomb the city again at night. The man looked at her and said, “I’m a friend of your husband, and I won’t tell anybody what you just said.” But then he showed us that he was from the secret police. He threatened that he could take her away without giving her the opportunity to say good bye to anybody. “But I’m your husband’s friend, and I’ll let you off this time. But you have to promise me to never say anything like that again.” My mother was a changed person after that. She had always listened to the English BBC radio broadcasts, but she stopped listening to it for fear that somebody would come to take her away.

On leave at home in 1944, Manfred Gellersen was ordained an elder by his father. After returning to the Eastern Front, he was involved in several serious engagements and was awarded the Iron Cross (both First and Second Classes). He was also wounded twice but recovered fully each time. In early 1945, he was stationed in East Prussia near the Baltic Sea coast. The Red Army pushed the German troops against the coast but did not complete the campaign because the Soviets were in a hurry to reach Berlin and end the war. Near the small port of Pillau, Manfred and several others put out to sea in a small craft and were fished out of the water by German sailors who transported them west to the harbor at Swinemünde. Working his way west toward home across northern Germany, he narrowly avoided capture by the advancing British army.

The branch history does not include any irregular statements during the last two years of the war. The Saints in that north German city were truly fortunate in that only one of their number died in the war, and nobody was homeless when the war came to an end. By then, the attendance at meetings had decreased to ten persons, but there is no explanation for this phenomenon. [10] The final entry in wartime follows: “On May 6 our branch meeting rooms were confiscated by the [British] occupation authorities. From now on we will have to hold our meetings in homes.”

Manfred Gellersen actually made it all the way home to Stade without spending a day in a POW camp. Moving across the flatlands of the Elbe River basin was difficult, but he stayed in ditches and out of sight until he was able to sneak into his own home like a burglar around three in the morning to surprise his family. However, once at home he could not show himself without the proper release papers. He soon reported to the local British military office, where he was instructed to go to a local POW camp to receive his release papers. As a civilian, he then visited his 1941 employer to ask for his job back, but the employer refused to hire him. Fortunately, there were plenty of jobs for a good mechanic, and Manfred began a new life with his family.

Looking back on his military experiences and his many medals, Manfred explained that he was not a hero. “The heroes are all dead,” he declared. “I never had to shoot my weapon at anybody, but they shot at me plenty often!” He never attended a Church meeting away from home, because there simply were none close to his duty locations. Conversations about religion were extremely rare, he explained, “because there was no religion in the German army I knew. And there were no Nazis either. Just soldiers. We just thought about winning the war.” Regarding the challenge of remaining a worthy priesthood holder at the front, he stated, “I had plenty of opportunities to fool around [and do sinful things], but I had a good foundation from home.”

The British had taken Stade without firing a shot, relieving the residents of the danger of any last-minute deaths trying to save Nazi Germany. Inge recalled her first interaction with the invaders: “They would stand next to their trucks and yell things like, ‘Hi, Blondie!’ I only spoke a little school English, and we had never learned about the word ‘Hi!’ so I wasn’t sure what they wanted to say. One time, they yelled, ‘Hi, Blondie! The war is over! We’re going home!’ All I could answer was, ‘Yes, go home!’”

The Stade Branch was still without an official home at the end of the summer of 1945 as the members continued to collect themselves again from the long conflict. “There were only a few of us left by then,” recalled Inge, “my parents and I and the Tiedemanns.” Their numbers grew over the coming months and included LDS refugees from the eastern provinces of Germany that had been ceded to Poland.

In Memoriam

Only one known member of the Stade Branch did not survive World War II:

Ernst August Tiedemann b. Schölisch, Stade, Hannover, 29 Sep 1911; son of Christian Ferdinand Friedrich Tiedemann and Margarethe Adele Catharine Marie Bröcker; bp. 18 Jul 1929; conf. 18 Jul 1929; m. 20 Jun 1933, Sophia Richter; k. in battle Eastern Front 21 Apr 1944. (FHL microfilm 68805 no. 7; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 829; IGI)

Notes

[1] Stade city archive.

[2] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[3] West German Mission manuscript history, CHL MS 1004 2.

[4] Stade Branch history, 236, CHL LR 5093 21.

[5] Inge Gellersen Long, interview by the author, Bountiful, Utah, April 10, 2009.

[6] Manfred Gellersen, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, November 3, 2006.

[7] Stade Branch History, 241, 243, CHL LF 5093 21.

[8] The attack on Stalingrad in the late fall of 1942 was to be supported by many divisions of soldiers from Germany’s allies, but when those divisions failed to move forward, the German Sixth Army was isolated and surrounded from the west by the Red Army. By the time the survivors surrendered in early February 1943, as many as 295,000 men were lost. Many Germans came to believe that the disaster of Stalingrad heralded the end of the Third Reich.

[9] Stade Branch History, book 2, 10, CHL LR 5093 21.

[10] Ibid., 17.