Nuremberg Branch

Roger P.Minert, “Nuremberg Branch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 305–323.

The Nuremberg Branch, the second largest branch in the West German Mission and one of the ten largest in all of Germany in 1939, had 259 members of record. It was a vibrant group of Saints when the war approached. The list of branch leaders compiled in July of that year shows that all Church organizations and programs were functioning, with the exception of the Primary organization (“because there are currently too few children”). [1]

Otto Baer was the president of the branch and was assisted by counselors Georg Strecker and Richard Schöpf. The former also served as the leader of the YMMIA and the latter as the president of the Sunday School. Berta Engel was the president of the Relief Society, Alma Klein the leader of the YWMIA, and Albert Frenzel supervised genealogical research in the branch.

| Nuremberg Branch [2] | 1939 |

| Elders | 23 |

| Priests | 9 |

| Teachers | 11 |

| Deacons | 20 |

| Other Adult Males | 26 |

| Adult Females | 139 |

| Male Children | 13 |

| Female Children | 18 |

| Total | 259 |

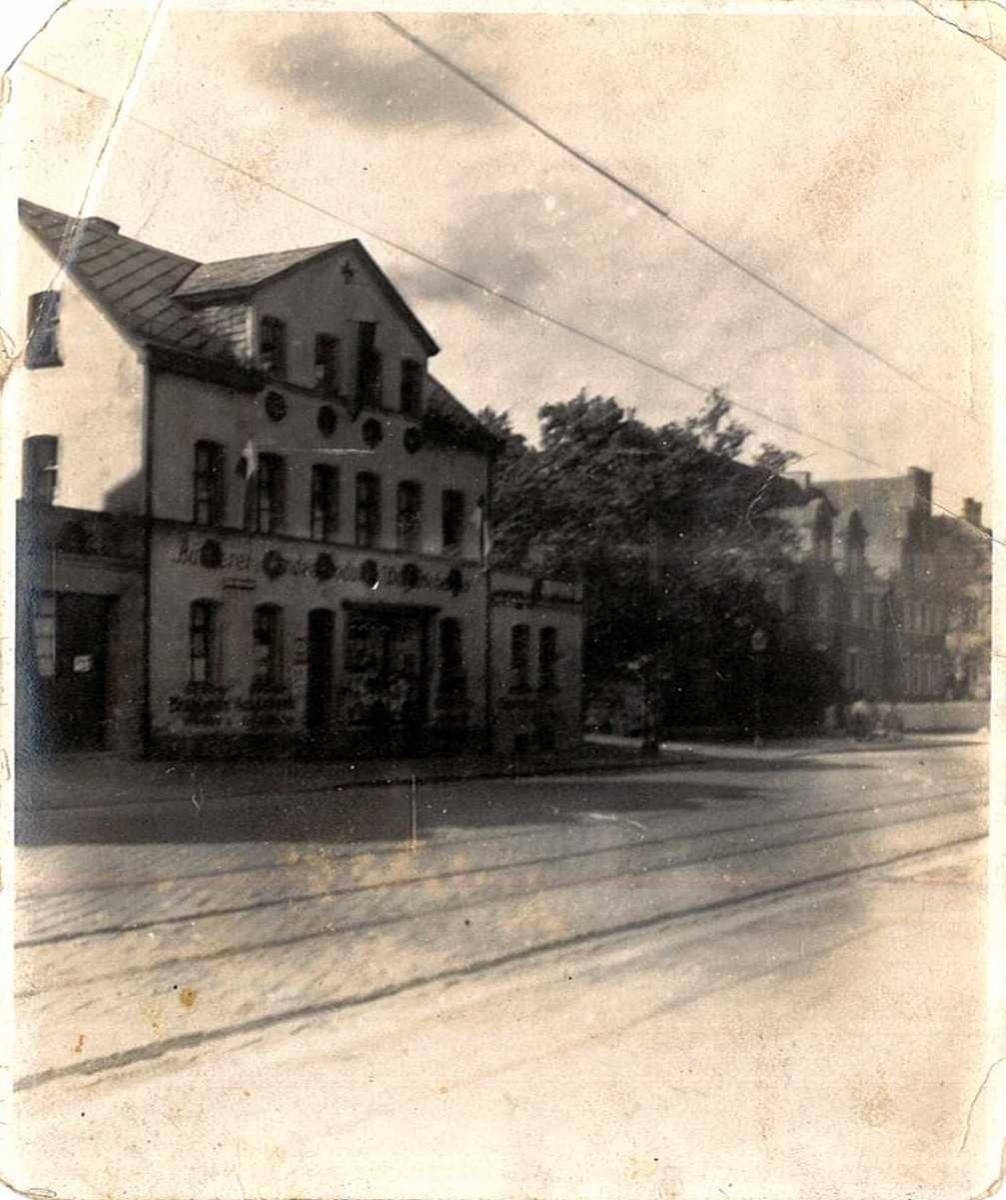

When the war began in September 1939, the Nuremberg Branch was holding meetings at Hirschelgasse 26. That small street is located in the northern part of the downtown, not far from the castle and the historic home of Albrecht Dürer, one of Germany’s most famous artists. Hirschelgasse was part of the core of the city that was still surrounded by a massive city wall when the war began. The neighborhood featured some of the finest structures of the Middle Ages crowded around several squares and along narrow streets. Perhaps one-fourth of the city’s 420,349 residents lived in that part of the city. [3]

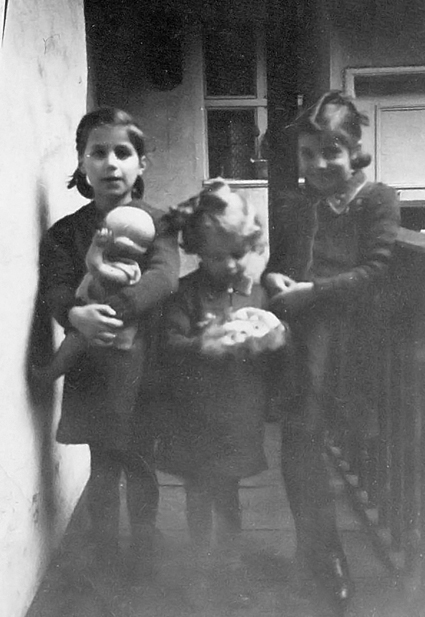

Fig. 1. TheGentnerfamily celebrating Christmas Eve in about 1938. (G.GentnerKammerer)

Fig. 1. TheGentnerfamily celebrating Christmas Eve in about 1938. (G.GentnerKammerer)

The first Sunday meeting was sacrament meeting at 9:00 a.m., and Sunday School followed at 10:50. The genealogical research group met every other Sunday at 7:00 p.m. Relief Society meetings took place on Mondays at 8:00 p.m., and the Mutual met on Wednesday evenings at 8:00.

The records of the West German Mission include no reports submitted by the Nuremberg Branch for the years 1939 to 1945, but this notice from the Church’s German-language magazine, Der Stern, dated October 22, 1939, is of interest:

The Nuremberg Branch moved from its rooms on Hirschelgasse (where they had met for eleven years) to rooms at Untere Talgasse 20. The city ordered the move due to the implementation of a new sanitation program. The dedication of the new rooms was attended by Otto Baer (branch president), Ludwig Weiss (president of the Nuremberg District), Johann Schmidt (president of the Fürth Branch), and Johann Thaller (president of the Munich District). [4]

According to Wilhelm (Willy) Eysser (born 1924), the rooms at Untere Talgasse 20 were better than those at Hirschelgasse. “We met on the third floor, and some branch members lived on the fourth floor. There were about 125 people in attendance at the time.” [5] Two families who were members of the Church lived in the same building—the Gentners and the Geudters, according to Gerda Gentner (born 1934). [6]

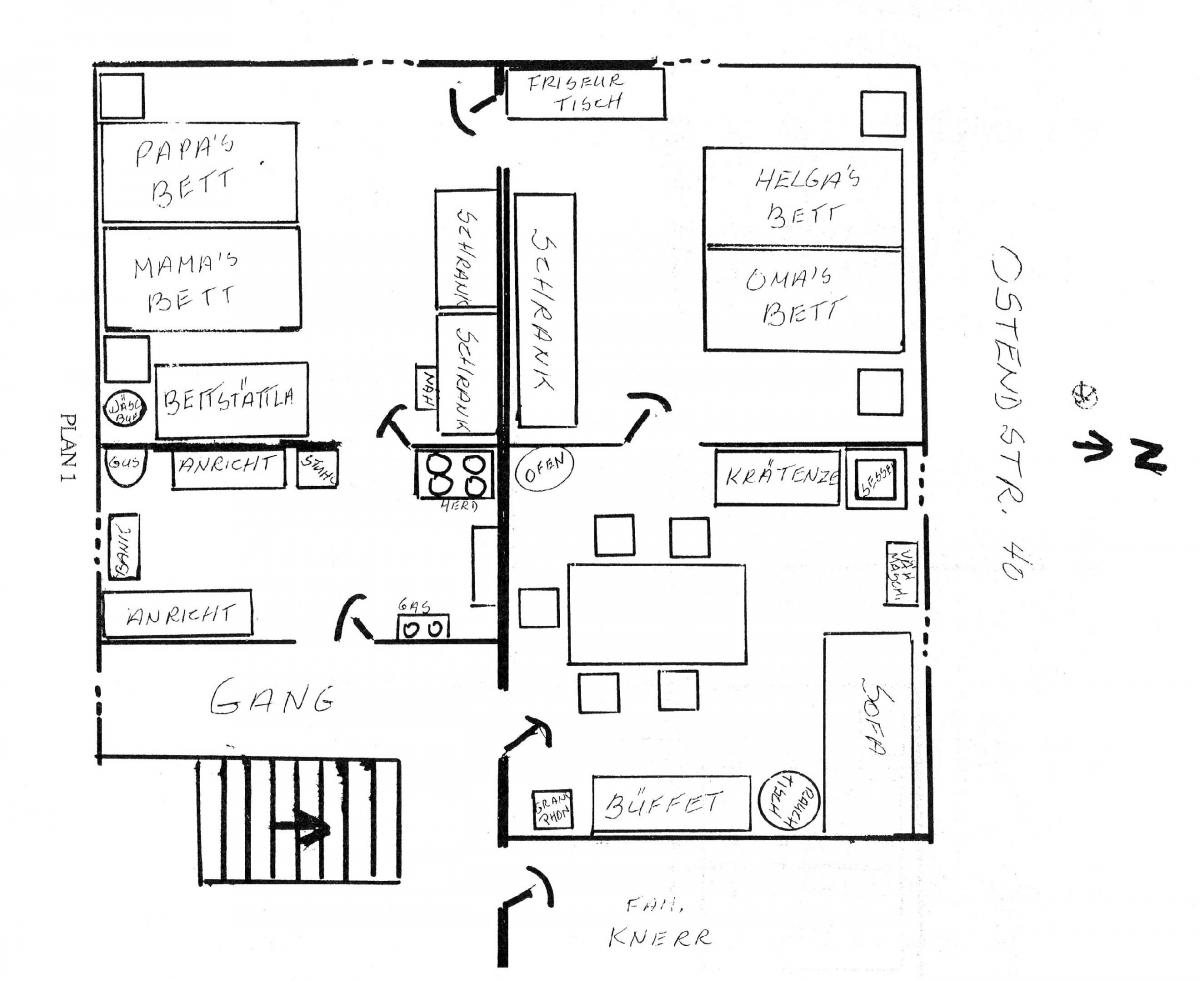

Fig. 4. Gerda Gentner (left) with her sisters Helga and Else in about 1941. (G. Gentner Kammerer)

Fig. 4. Gerda Gentner (left) with her sisters Helga and Else in about 1941. (G. Gentner Kammerer)

Waltraud Weiss (born 1930), a daughter of the district president, provided more detail about the new meeting rooms:

The owner of the building had attended Sunday School as a boy (but had not joined the Church) and helped us any way he could. The rooms were tall and had very ornate ceilings. We removed one wall to make the main meeting room larger. We heated the rooms with coal. There was a patio behind the building with a backyard that was open to everybody. [7]

The family of Ludwig Weiss lived in the suburb of Lauf am Holz. From that location, they walked about thirty minutes to reach the streetcar that took them to church. Between Sunday meetings, they usually did not go home again but rather stayed in town with other branch members.

Helmut Schwemmer (born 1933) recalled two significant prewar events with remarkable clarity. The first was the Reichskristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) of November 9, 1938:

Our whole family was awakened by this terrible noise of breaking glass and screaming. My dad told us that it was the Nazi SA men (Hitler’s special bodyguards) on a rampage in the neighborhood. The next morning we found our favorite bakery across the street completely demolished and the owners were nowhere to be found. [8]

He learned years later that this violence meant the end of many of the Jews who had not yet left Germany.

The second prewar event of great significance in the life of young Helmut Schwemmer was the Nuremberg Party Rally. An annual spectacle, the rally brought tens of thousands of soldiers, Nazi Party members, and civilians to the city. Helmut recalled watching workers erect viewing stands along the route from the main station to the party rally grounds at Luitpoldhain, passing within a block of Helmut’s apartment house. He later wrote:

As a six year old I was awed by the never ending columns of soldiers, tanks, cannons, bands and other army equipment. The highlight of the parade was of course when all participants were in the stadium and Hitler and his cronies made their speeches which lasted for hours. . . . This same show was repeated every day for a week. . . . The Hitler Youth choir I belonged to marched in the parade on one of the days during the week dedicated to the Hitler Youth of Germany. Although I could not see much of what was going on, . . . three things transpired which are permanently etched into my memory: (1) the booming voices of the speakers—especially Hitler, . . . (2) the deafening and seemingly endless cheers of Sieg Heil, . . . (3) the lighting of thousand of torches in the evening. [9]

When the American missionaries were evacuated from Germany on August 25, 1939, many of the local Saints were sad and concerned about the future. Those emotions may not have been obvious to young Lorie Baer (born 1933), but she did recall vividly that “the American missionaries knocked on the door in the middle of the night and said, ‘Brother Baer, we are called home!’ They gave my father all the materials they used in their missionary work such as books.” [10]

Walter Schwemmer (born 1931) was baptized in the Pegnitz River in Nuremberg just weeks after the war began. He recalled:

We went there late at night. We didn’t really want anybody who was not a member of the Church to see what was happening. My uncle, Christian Schwemmer, baptized me. We had our pajamas on, and it was cold outside. After the baptism, my dad took us home on his bicycle while we were still wet. After all, it was October. [11]

Elisabetha Baier (born 1906) had married Georg Strecker (born 1906) in 1932, and they had two daughters by the time war broke out in 1939. Georg worked at the Mann munitions factory, and Elisabetha had a sewing job at home. Because Georg was a member of the branch presidency, the police came to the Strecker home twice during the war to search for Church books. According to Elisabetha, “The police felt the Mormon Church was an American church so they were suspicious of us.” [12] Nothing ever came of the investigation.

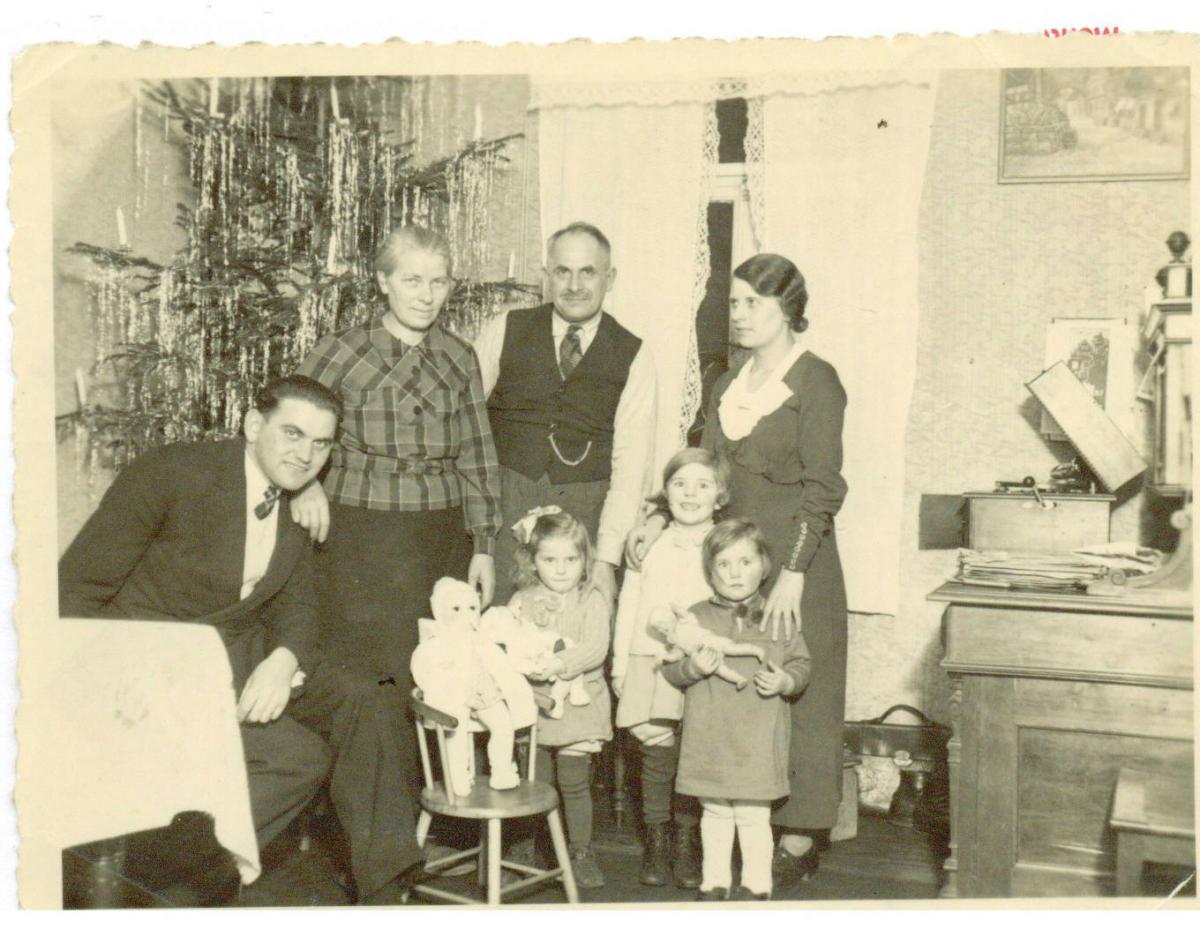

Branch president Otto Baer owned and operated a health food store not far from the main station in Nuremberg. His daughter, Lorie, recalled how the Nazi Party compelled her father to join in order to maintain his business. She claimed that her home was one of the first to be destroyed in Nuremberg when enemy planes targeted the main railway station nearby. It was a most frightening experience for which the family was not at all prepared:

We were in the shelter, and when the attack was over, my mother ran upstairs and grabbed a suitcase. . . . We also grabbed a bottle of mineral water and a handkerchief for everybody and made sure that we held the wet handkerchief over our mouths. The street in which we lived had about sixteen large apartment buildings. Of those, only three were not hit that night. By the time we got out of our basement and grabbed our things, everything on the street was burning. We stood at the end of the street and looked back—everything was gone. We could only take what we had on, and that was it. This was in the middle of the night. My mother looked at me and said that we have to leave. She had a very close friend with whom we could stay. I called her Aunt Käthe because we ended up staying with her for three years. We knocked on her door in the middle of the night, and she let us in and gave us a safe place to stay. The next morning, my mother went back to our home to see if there was still something there, but everything was gone.

Fig. 2. Otto and EllaBaerwith their daughter, Lorie, in the doorway to their health food storeKräuter-HandlungBaerin 1938. (L.BaerBonds)

Fig. 2. Otto and EllaBaerwith their daughter, Lorie, in the doorway to their health food storeKräuter-HandlungBaerin 1938. (L.BaerBonds)

Shortly after the war began, branch president Otto Baer was drafted. He spent most of the next six years away from home in such places as Poland, France, Romania, and Russia. Initially, he was succeeded by Paul Eysser, who in turn was drafted and replaced by Ludwig Weiss, who was still serving as the district president. [13]

Waltraud Weiss was inducted automatically into the Jungvolk program in her school at the age of ten. She recalled, “I had piano lessons on Wednesdays after school and couldn’t participate in the meetings. On Fridays, my mother had a sewing class, so I couldn’t attend on those days either. But I made sure to attend a few times, just to stay out of trouble.”

“When you were a woman [during the war], you had to be in the work force, and your children were left alone throughout the day,” recalled Marie Strecker Mördelmeyer (born 1912). [14] She had married in 1935 and had two daughters, Annemarie and Helga, before the war started. “When the sirens would sound an attack, the children had to flee to the bomb shelter alone, and I never knew in what part of town they were. My husband was a soldier, away from home from the years 1939 to 1945.” The burden on mothers raising their children alone during the war was extremely heavy in many respects.

Fig. 5. HansEysser(far right) as a new recruit at aWehrmachtpost inAnsbach, Bavaria. An elder in the Nuremberg Branch, Hans was killed in Russia in 1942. (W.Eysser)

Fig. 5. HansEysser(far right) as a new recruit at aWehrmachtpost inAnsbach, Bavaria. An elder in the Nuremberg Branch, Hans was killed in Russia in 1942. (W.Eysser)

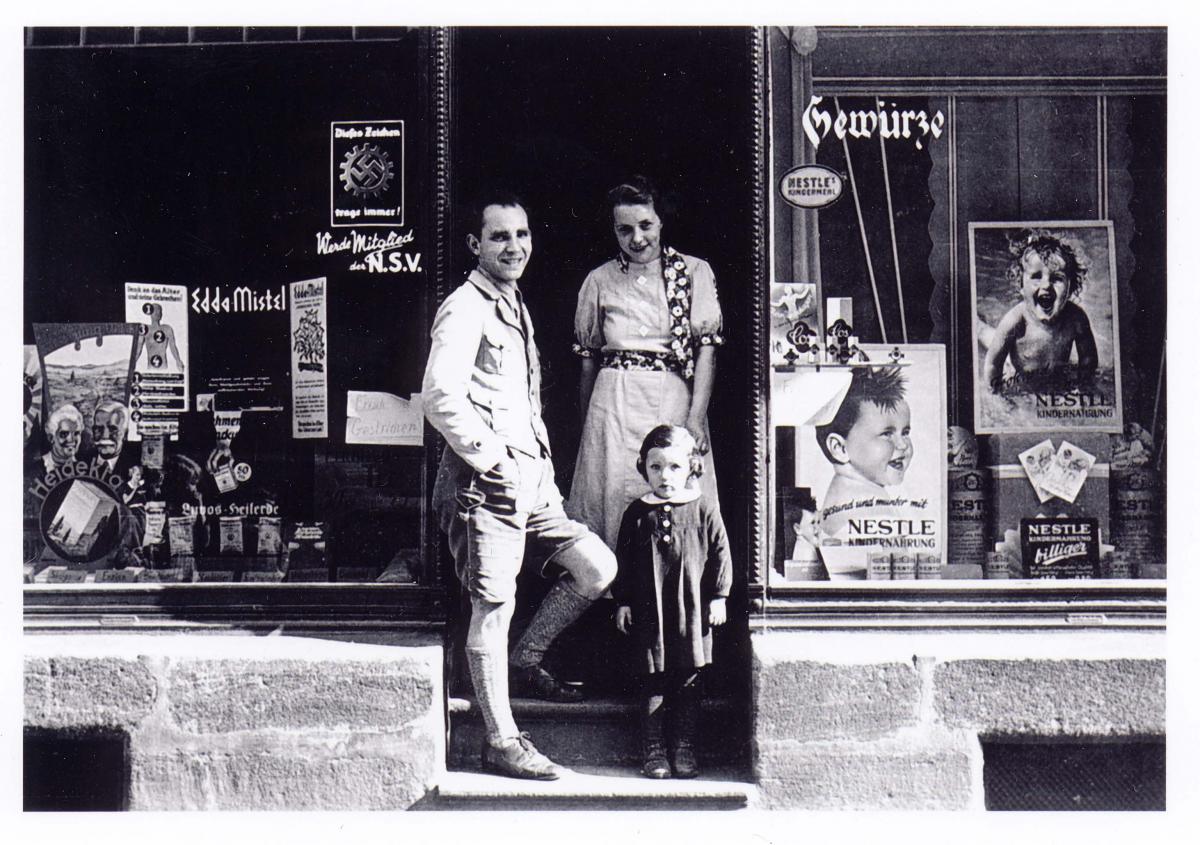

Fig. 3. The floor plan of theMördelmeyerapartment atOstendstrasse40 in Nuremberg. The family lived there from 1935 to 1944.Tisch= table,Bettstättla=bedstand,Schrank= closet, Gang = hall,Anricht= cupboard,Sessel= overstuffed chair,Stuhl= chair. (H.MördelmeyerStrauber)

Fig. 3. The floor plan of theMördelmeyerapartment atOstendstrasse40 in Nuremberg. The family lived there from 1935 to 1944.Tisch= table,Bettstättla=bedstand,Schrank= closet, Gang = hall,Anricht= cupboard,Sessel= overstuffed chair,Stuhl= chair. (H.MördelmeyerStrauber)

“When I was ten years old, I was inducted into the Jungvolk,” recalled Walter Schwemmer. His story continued:

Actually, it was not mandatory, but they put so much pressure on the parents that they eventually decided to send their children to the activities. I was a part of the Hitler Youth later on [age fourteen] too, and I attended the meetings. They never interfered with Church, though. I can’t actually remember what we did exactly, but I know that it had to do with sports. I liked those activities. We also marched.

Lorie Baer was sent to live with her aunt in 1941. Her mother felt that the little girl would be safer in a small town and could attend school without constant interruptions. Lorie lived with her aunt for an entire year, sleeping in a storage room and eating with a different family. It was an unhappy time, as she recalled:

As soon as classes were over on Friday afternoon, I would take a train back home to Nuremberg. I was seven years old at the time, and it was scary. I wanted to spend the weekend with my mother. I even had to change trains in the middle, and I waited for forty-five minutes for the next train to come. Every Sunday afternoon for a year, I cried and cried because I had to leave my mother again. . . . After a year I was so homesick for my mother that I said to her that if she got killed, I wanted to be also, and I stayed home with her.

Back in Nuremberg, Lorie lived with her mother again in the apartment house the government had since rebuilt for them and their neighbors.

Little Helga Mördelmeyer recalled how her father was assigned as a dog handler in the army. During training sessions conducted in a nearby town, he taught his German shepherd to sniff out partisans on the Eastern Front. “He would come home on weekends, but he was not allowed to bring his dog. He later told us that his dog had often saved his life during difficult times. When it was a cold night in Russia, the dog would lie down right next to my father and keep him warm. . . . The dog protected him.” [15]

Schoolteachers in Nazi Germany were state employees and were required to belong to the National Socialist Party. Although not all were believers in the Nazi philosophy, one of Waltraud Weiss’s teachers apparently was. She explained: “When I was in sixth grade, I had a teacher who was politically involved and wanted to teach us those things. The first thing he did every morning was to read aloud from the newspaper the accomplishments of the government. We were actually supposed to learn many other things, but for him, it was more important that we know about current events and politics.”

“You always had to salute and say ‘Heil Hitler!’ when you entered a store,” recalled Oswald Schwemmer (born 1935), “or they would question you.” Oswald’s father, Christian Schwemmer, was a tailor who operated his own business on the main floor of an apartment building on Angerstrasse, just south of the main railroad station in Nuremberg. The Schwemmers joined their neighbors in the basement when the air-raid sirens wailed. During one attack, a bomb fell close by, and the vibration caused the door to the furnace ash removal chamber to fly open. As Oswald recalled, “Everybody looked black as Negroes from the soot.” [16]

Oswald soon learned that air raids were not bad in every regard; there were advantages for little children. Besides having fun collecting pieces of metal from bombs and antiaircraft shells, the children found other treasures to gather: “There was a toy factory nearby. We had the time of our lives going through the rubble [of the factory] finding toys and stuff.”

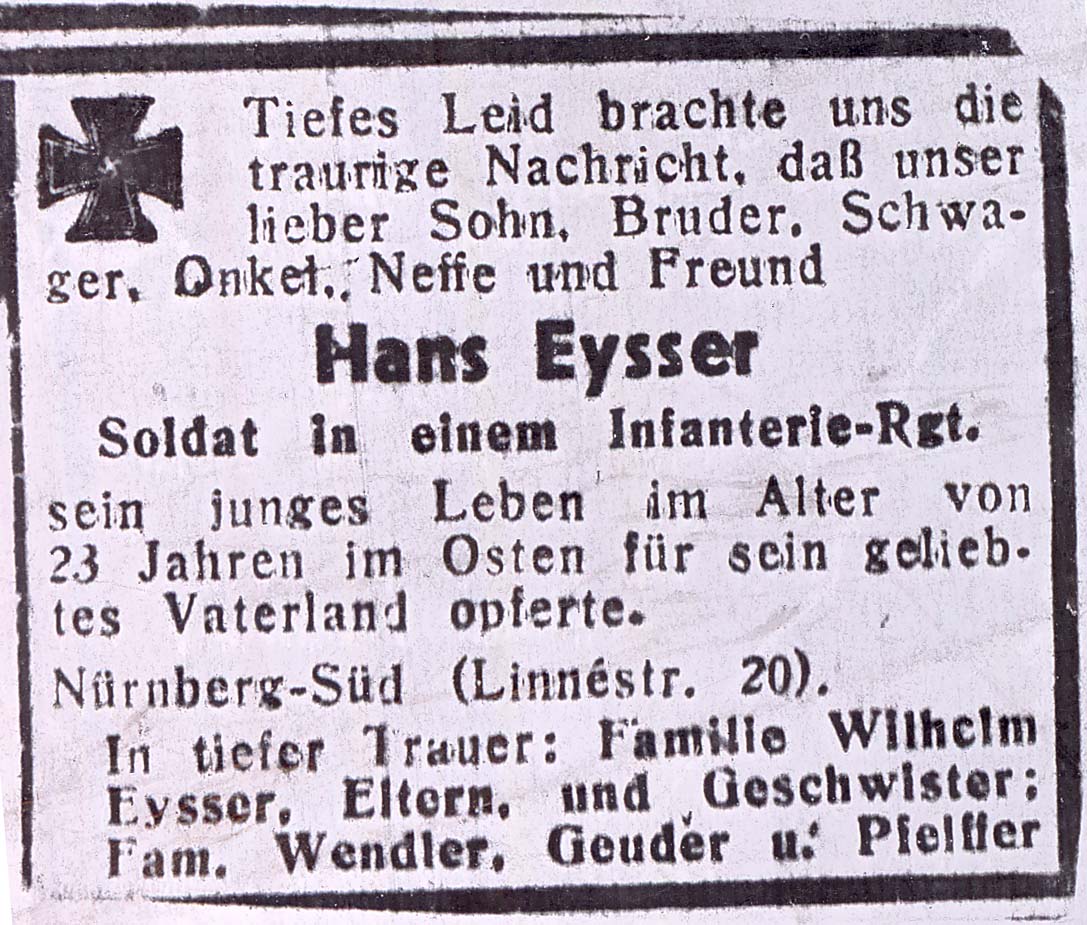

Fig. 6.This notice was printed in a Nuremberg newspaper in April 1942. It reads in part, “It is with deep sadness that we received the news that our dear son, brother, brother-in-law, uncle, nephew and friend, HansEysser, a soldier in an infantry regiment, sacrificed his life on the Eastern Front for his beloved fatherland at the age of twenty-three years.” (W.Eysser)

Fig. 6.This notice was printed in a Nuremberg newspaper in April 1942. It reads in part, “It is with deep sadness that we received the news that our dear son, brother, brother-in-law, uncle, nephew and friend, HansEysser, a soldier in an infantry regiment, sacrificed his life on the Eastern Front for his beloved fatherland at the age of twenty-three years.” (W.Eysser)

Waltraud Weiss described being sent home from school when the first air-raid alarm sounded: “When I rode the train home [to our suburb], it would not stop but would roll slowly through the station, and we had to jump off.” At home, her parents listened to forbidden radio broadcasts from the Allies in order to receive advance warnings about air raids. Waltraud’s account continued: “Hearing the sounds of the planes and seeing the ‘Christmas trees’ [flares dropped by the attackers to mark the bombing targets] made me scared, but at least we knew where the bombs would fall.”

In 1942, at the age of ten, Hermann Baer (born 1932) was inducted into the Jungvolk. As he recalled:

I didn’t want to go, so they came to my home and told my parents that if they didn’t send me to the Hitler Youth, they would be arrested. So I had to go in order to protect my parents. It was like being in the Boy Scouts, but the indoctrination was different. They trained you to believe what they told you to believe. [17]

Ella Paula Baer traveled to Schweinfurt on one occasion with her daughter, Lorie, to visit relatives. Just as they boarded the train for home, enemy planes attacked the railroad station, and chaos broke out. A bomb hit the car they were in, and Lorie was suddenly surrounded by dead travelers. Her story continued:

My mother had fainted, and I thought she was also dead. I dragged my mother out of the train, being eight years old. The minute I got her out of there, another bomb hit the train. After that, everybody was dead. I think it was only my mother and I and maybe one other person who survived that attack. My mother then went to look for our luggage while I stayed where she left me. While looking for our things, my mother stepped on a mine, and it exploded. All that happened to her was that she lost a heel. That was all. But the people around her got hurt.

Helga Mördelmeyer started school in 1942. Because she was neither Catholic nor Lutheran, she had to sit around and “do nothing for an hour during the religion class. The teachers didn’t make fun of [my sister and me], and the other pupils didn’t care much.” In the fall, Helga contracted pneumonia and was hospitalized. In her recollection, “during air raids they put all of the children in the halls, far away from the windows. When I came home, I saw that two buildings in our neighborhood had been bombed.”

The year 1942 was tragic for the Schwemmer family. In October, Heinrich Schwemmer was killed in Russia. His son Walter recalled that two Nazi Party men in uniform knocked at the family’s door one evening and informed Sister Schwemmer that her husband had given his life for his country. Later, she learned that Heinrich was killed trying to save his lieutenant, who had been wounded by a land mine. The man wanted to shoot himself, but Brother Schwemmer was able to convince him that his pregnant wife needed him back home. The lieutenant surrendered his pistol to Heinrich, who also stepped on a mine and sustained wounds from which he bled to death. The lieutenant made it home to Germany and wrote to Sister Schwemmer to explain the circumstances of Heinrich’s death.

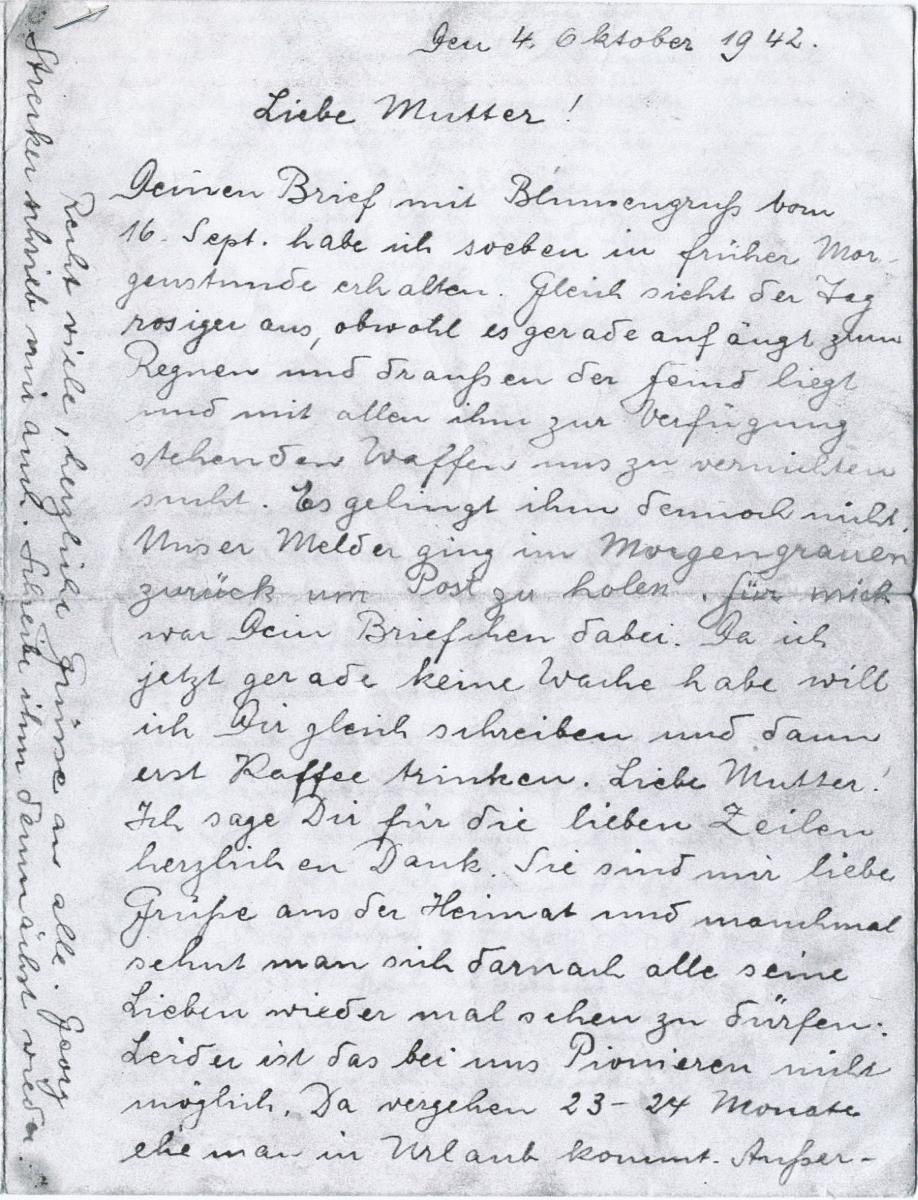

Just eleven days before he was killed, Heinrich Schwemmer had written home to his mother:

Tine has probably told you that I have been wounded three times already. I hope that there will not be another time and that I can come home as I am now [healthy]. The first time was on June 6 (three pieces of shrapnel), the second on August 18 when we were attacked by a dive-bomber (three bomb fragments), and the third on September 5 (two more pieces of shrapnel from heavy artillery while we were clearing land mines). . . . I still have five pieces of metal in me; they can be taken out after the war if they are causing me trouble. . . . My dear mother, you didn’t raise any cowards, but rather seven men who can find their place in the world. . . . I can look death calmly in the eye, if it absolutely must be so. . . . May you be privileged to see your seven soldiers return from the front in good health. [18]

It is not clear whether the letter Heinrich wrote on October 4 arrived in Nuremberg before the news that Heinrich had been killed.

Fig. 7. Letter written by Heinrich Schwemmer to his mother just eleven days before he was killed in Russia. (W. Schwemmer)

Fig. 7. Letter written by Heinrich Schwemmer to his mother just eleven days before he was killed in Russia. (W. Schwemmer)

Later that year, Walter Schwemmer was evacuated to a place near Leitmeritz, Czechoslovakia, along with his entire class of boys and their teacher. He described his new setting in these words:

We lived in the residence of a bishop of the Catholic Church. We had to wear our Hitler Youth uniforms very often and had to take care of them and wash them ourselves. We even ironed them. . . . We stayed there for two and one-half years—totally isolated from the Church. It was difficult being so far away from home. I think I was the only Mormon in that group. We attended the religion class at school, and I chose to attend the Protestant class.

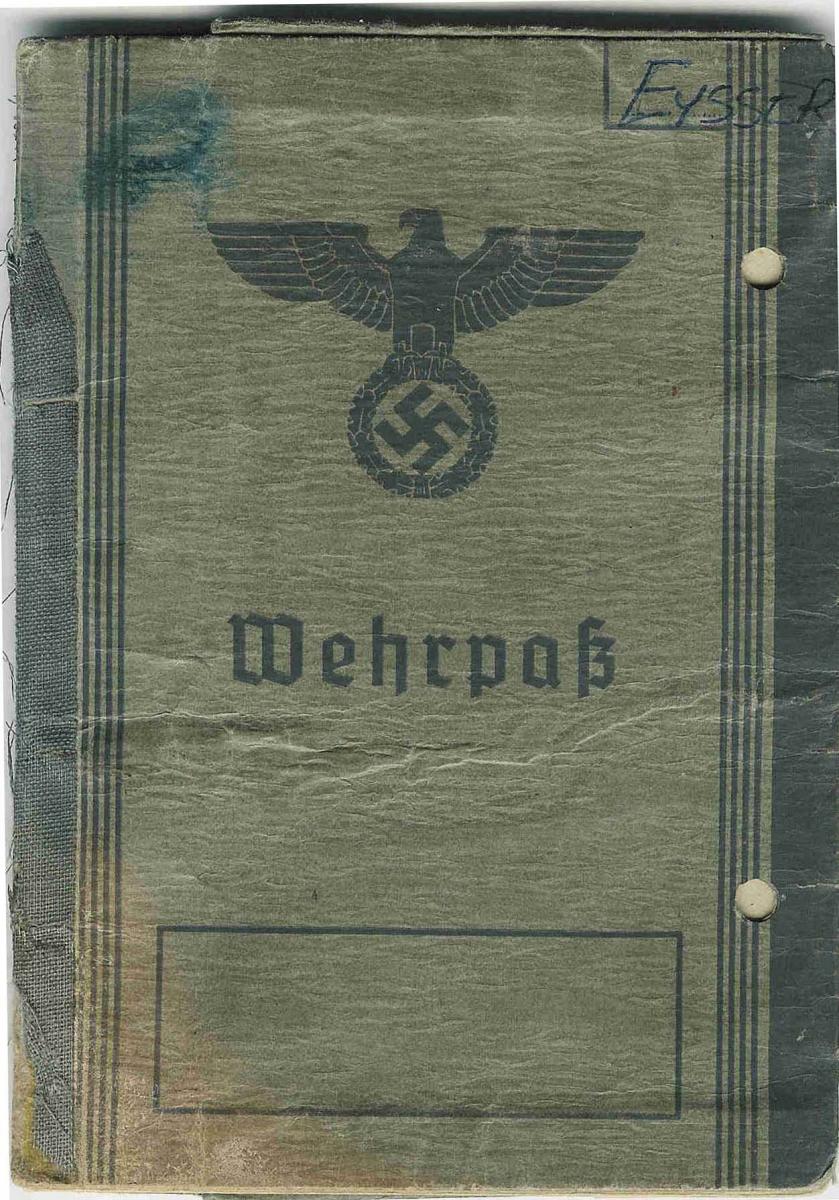

“I was drafted by the Wehrmacht in December 1942, but I didn’t want to go,” recalled Willy Eysser. Of course, there was no other option but prison for refusing to serve in the military, so Willy and his brethren in the Nuremberg Branch reported for duty when called. His religious experience as a soldier over the next few years was typical of German LDS men: “I was a teacher in the Aaronic Priesthood at the time. I never saw another member of the Church who was also a soldier. I couldn’t attend any meetings while I was in the military. . . . I couldn’t partake of the sacrament the entire time, and I also didn’t have my scriptures with me.” Nevertheless, he attended church meetings on the few occasions when he came home on leave.

One particular air-raid experience remained clear in the memory of Elisabetha Strecker years later:

One August [1943] night the siren warnings went off. . . . Usually when the sirens went off we had ten to fifteen minutes to get to the bunkers before the bombs started falling. But that night there was no [first] warning. As George, myself, and Brigitte left our apartment we walked out on the street and the upper street had already been bombed and was in flames. We ran as fast as we could, and George and I literally had to drag Birgitte to the bomb shelter. . . . I think it was the worst night I ever experienced. [19]

In October, the Strecker apartment was damaged, and the family lived with a woman in the branch named Sister Paulus for the next three months.

Waltraud Weiss recalled the efforts expended by her father to repair their apartment after it was damaged in an air raid in August 1943:

My father tried his best to rebuild everything so that we could at least live in the house again. We received permission to use the materials in the ruins of the neighbor’s house to repair our own. In March 1944, phosphorus bombs landed on our property but were stuck in the wrought iron and didn’t get inside the house. My uncle was close enough to the bomb to have his hair singed.

Fig. 8. Members of the Nuremberg Branch on their way home after Sunday School. (L.BaerBonds)

Fig. 8. Members of the Nuremberg Branch on their way home after Sunday School. (L.BaerBonds)

Marie Mördelmeyer lived with her two daughters in an apartment at Gugelstrasse 102. Like most residents of large cities in Germany, they usually sought shelter in their basement during air raids. One night, a bomb hit the adjacent building. She recalled, “I believe there were 42 persons dead. They burned to death. In that night I took my two kids under my arms and my prayer was, if it should hit us also that our Heavenly Father will make it quick. But our lives were spared. . . . We lost all that night.” Sister Mördelmeyer was able to find a single room for her four-member family in the apartment building in which her parents lived. The family stayed there until November 1945. [20]

Young Annemarie Mördelmeyer (born 1935) explained that going to church meetings was a real challenge. [21] Her family had to be on constant lookout for a shelter to hide in if the air-raid sirens suddenly went off. In her recollection, church meetings were rarely interrupted once they started, but sirens were heard many times on their way home—a walk that took about a half hour. Little children were often left home during the evening meetings because travel was complicated and their sleep patterns needed to be maintained if possible.

“The government wanted to send my sister and me away in the Kinderlandverschickung program,” recalled Annemarie:

My mother would only let us go if she was given permission to come with us and leave her work at the munitions factory. She was told that they wanted to save the lives of the youth, not the lives of the old. My mother then explained that we would all stay together right where we were. They told her that she would have to go to a concentration camp. My grandmother then explained that she would also take care of us. Then we were able to stay home.

Fig. 9. WillyEysser’smilitary service record, like that of millions of German soldiers, airmen, and sailors. It measured 4 inches by 5¾ inches. (W.Eysser)

Fig. 9. WillyEysser’smilitary service record, like that of millions of German soldiers, airmen, and sailors. It measured 4 inches by 5¾ inches. (W.Eysser)

Friedrich Frenzel was an employee of the national postal system but an outspoken opponent of the Nazi Party. His son, Benjamin (born 1936), was aware of his father’s attitude, and that apparently was clear to his schoolteacher. Fortunately, she took steps to prevent any trouble, as Benjamin recalled:

When the Gestapo came [to school], she had the feeling that she should do something to protect me. I sat in the very front row, in front of her desk. The day the Gestapo came to visit, she put me at the very back on the left side of the classroom. As soon as the Gestapo entered, the children would have to raise their arms in order to say “Heil Hitler,” and she was very much aware of the fact that I never did that. . . . The Gestapo did not ask any questions. My teacher was even a member of the Nazi Party but only because the law required her to be. [22]

Fig. 10. TheEysserfamily during the war. (W.Eysser)

Fig. 10. TheEysserfamily during the war. (W.Eysser)

Many Germans took pity on foreign prisoners of war and workers from other countries. Benjamin’s mother, Katharine Frenzel, was one such sympathetic German. Benjamin recalled an odd incident that happened one day when they entered their garden space in a public garden district:

My mother went in, and we were still waiting at the gate. Suddenly she started screaming, turned to us, and told us that we had to leave. The woman in the garden next to us wanted to know why my mother suddenly wanted to leave. My mother lied and said that a rat had run across her feet. Instead, there was a [foreign] prisoner of war hiding among the bushes. The authorities had divided the garden area into two parts and made a prison camp out of one half. Mother gave the man the sandwiches that she had brought for us and left him there, telling nobody that she had seen him. If somebody had found out that she lied, she could have been punished for treason.

The childhood memories of Helmut Schwemmer constitute a collage of life in wartime:

Days and days without having to go to school because of the nightly air raids; sitting in the cellar on Mom’s lap listening to the bombs explode all around and being very scared; the putrid smell of houses on fire and bombed out old buildings; windows covered with black cloth and inspected from the outside every night for the slightest amount of light shining through . . . ; collecting and trading bomb fragments; Hitler Youth boys choir; . . . collecting pencil lead–like “fire sticks” from partially burned firebombs and making firecrackers with them; one of my friends lost half of his face and an arm when a firebomb he was trying to dismantle blew up in his face. [23]

Walter Schwemmer recalled an occasion when he nearly lost his life to a dive-bomber. “We were in our garden house at the time, and I told everybody to duck down when the plane approached. The bullets went right through our house, and I remember one flying right over somebody’s head. We were glad that he didn’t stand up [right then].”

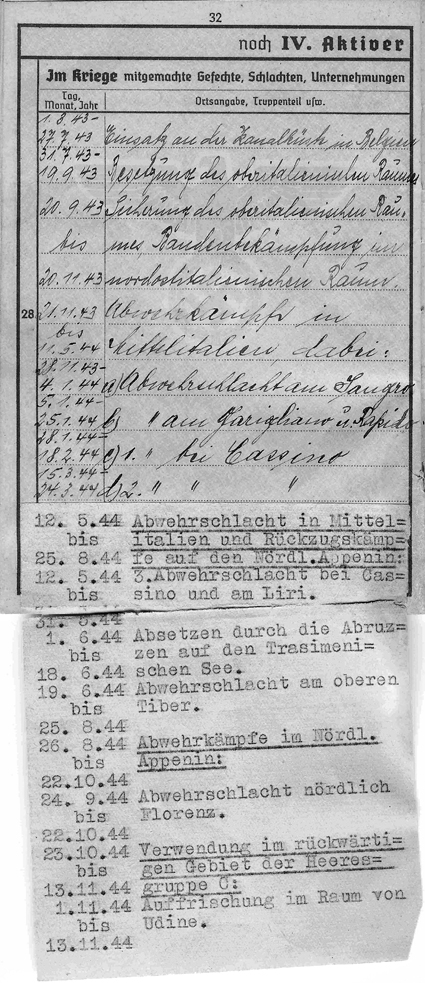

Willy Eysser described one combat experience in Hungary:

On May 7 1944, I was wounded. I was hit in the left leg, and it hit a nerve, so I was not able to move my leg for a while. They took me to a field hospital in the middle of nowhere. They put me in the back of a room and laid me on my stomach, so I wasn’t able to drink or eat anything because I couldn’t keep it down. It was a while before I was able to walk again.”

Following his recuperation, he was allowed to go home for a rare visit.

Fig. 11. Willy Eysser’s military service record did not have enough space to record all of his combat experience, so a sheet was attached. (W. Eysser)

Fig. 11. Willy Eysser’s military service record did not have enough space to record all of his combat experience, so a sheet was attached. (W. Eysser)

While Christian Schwemmer was away at war and his tailor business was discontinued, his wife, Babette, took their children away from the big city to the farming community of Ehlheim, twenty-five miles to the southwest. There they lived in total isolation from the Church, but Babette’s son Oswald recalled how she “taught us the principles [of the gospel] and prayed with us.” She read to her children from the scriptures and taught them through example, but it would be several years before they would attend church meetings in Nuremberg again.

According to Oswald, the town of Ehlheim consisted of about seventeen farmers and their families. To attend school, he had to walk two miles to Dittenheim: “This was OK in the summertime, but in the winter or rain, it was terrible. The road was not asphalt, and it was very muddy when it rained, and in the winter it got very cold, and the snow was very high.” To young Oswald, the distance to school seemed twice as far as it really was.

It was not uncommon in those days for parents to attend sacrament meetings on Sunday evenings while their children stayed at home. Such was the case one Sunday in the George Strecker home. Two daughters, Wanda (born 1935) and Brigitte (born 1938), stayed at home, and for their safety, their parents locked the apartment door from the outside with a large key. During the sacrament meeting, the air-raid sirens sounded, and the little girls could not leave the apartment for the basement shelter. Brigitte explained what happened next:

My sister and I pulled out a chair, and we knelt down and said a prayer. My sister said a beautiful prayer, and she was [nine] at that time. I think I was only [six]. And so, about fifteen or twenty minutes later, my parents came. But you know, we knew what to do as children. We knew that Heavenly Father would watch over us, and he touched us, and we knew that. And when they came we were so happy, of course, to see them, and nothing happened to us, and they came home as quickly as they could. [24]

Young Benjamin Frenzel experienced enough air raid alarms and attacks to recall the alarm sequence vividly: “The first alarm meant that there was a possibility that the enemy would come. The second alarm meant that we had to get ready for sure and head to the shelter. When the third alarm sounded, we knew that the enemy would only need five to seven more minutes to attack.” On one occasion, a Gestapo agent was checking the identification papers of people entering the bomb shelter. “My father did not have his with him. He then went up to the castle, where he found another shelter. My mother and all of my siblings at that time stayed close to our home.” [25]

Friedrich Frenzel attempted to construct a radio that could receive broadcasts from stations beyond the German borders—something the common German radio could not do. The activity was also strictly forbidden. According to his son, Benjamin, local merchants became aware of Brother Frenzel’s designs:

One day, the Gestapo came to our door, and we could hear those boots in the hallway. It just so happened that my father was home. My father put his fingers to his lips to indicate that we needed to be extremely quiet. We obeyed. He waited, and they knocked and knocked again. He did not open the door. We heard them walk away, and we wanted to jump up again to play, but my father put his fingers to his lips again. It seemed like we sat there for twenty minutes doing absolutely nothing. We then heard some more boots in the hallway walking away. My father had known that there were at least five men standing outside the door. Even fifty minutes after the initial knocking, we still heard them walk away. We were then allowed to get up again to play.

In the summer of 1944, Helga Mödelmeyer turned eight and was baptized. “I think that Brother Schwemmer baptized me and my uncle confirmed me. That took place at the indoor swimming pool. We waited until everybody was out of the pool. Two or three others were baptized that night, too. I think Oswald Schwemmer was one of them.”

Ferdinand Schwemmer (born 1934) recalled a frightening experience his mother had on a shopping expedition late in the war:

Our mother went into town once in order to find food for us. She was at the main town square when an air raid started, and she went into the big public bunker. When the attack was over, she had the feeling that she needed to get out of the bunker as soon as possible. The [wardens] didn’t want to let her out yet, but she forced her way out anyway. As she hurried toward our house, the attackers came again. They dropped aerial mines, and one hit the city square where my mother had just barely left the bunker. All the people in the bunker were killed. My mother was so lucky that she left. She explained that she just had this feeling, and she knew she had to follow through with it. [26]

Ferdinand also recalled that his parents had a little house just north of the city prison near the railroad yards. [27] The small home could not have withstood a bomb, so Sister Schwemmer was compelled to take her children to the nearest public shelter, at least fifteen minutes away on Layerstrasse. According to Ferdinand, “We were late getting to the bunker many times, and bombs would be falling before we got there. We hid in a ditch and prayed that we would get out of the situation alive. My mother [crouched] over us to cover us, and we waited until the attack was over. We heard people screaming, and it was really scary.”

The new year 1945 began in a most tragic way for the city of Nuremberg. Allied airplanes flew over on January 2 and dropped more bombs that night than during all previous attacks combined. The core of the city was almost totally destroyed, and countless architectural, historical, and artistic treasures were lost forever. Several thousand residents died in the attack, and tens of thousands were rendered homeless. According to Waltraud Weiss, the branch meeting rooms at Untere Talgasse 20 were destroyed that night.

Annemarie Mördelmeyer recalled clearly the night of January 2:

The night before, all of Nuremberg looked like it had layers of sugar everywhere because it had snowed. It looked beautiful with the full moon. It was so peaceful, and no alarm destroyed that peace. On January 2, we sat on benches in the basement, which was not larger than twenty square meters. My mother always sat in the middle and put her arms around us to make us feel safe. We heard the bombs falling; the noise was unbearable, and we knew exactly what it meant for us. Afterwards, there was no snow anymore—we experienced a [fire-]storm that night, with lots of wind pulling us toward the burning buildings. It was horrible. I would say that every third house was in flames that night. I saw the bodies of the people who used to live in the neighboring house. As children, we wanted to see it because it was something we had never seen before. But our mother didn’t want us to look. The bodies were so much smaller than we would have ever thought. The smell wasn’t pleasant.

Her sister, Helga, also had vivid memories of that night: “There was a young woman in our apartment building who had gotten married on Christmas Day. She died during that horrible air raid. I watched the entire city burn the next day. We didn’t really go to school after that because there weren’t any buildings available or teachers, for that matter.”

Fig. 12. TheMördelmeyerfamily lived in this house onOstendstrassewhen the American army arrived in April 1945. (H.MördelmeyerCampbell)

Fig. 12. TheMördelmeyerfamily lived in this house onOstendstrassewhen the American army arrived in April 1945. (H.MördelmeyerCampbell)

Although not quite five years old at the time, little Zenos Frenzel (born 1940) saw things that night that he could never forget:

When we came out of the shelter, the city was burning brightly. We had to get out of the city somewhere, which was the only solution. And while we were walking, the walls of the houses we passed collapsed next to us, which could have hurt us very badly. It was a weird feeling because the city was so hot although it was in the middle of winter. When we arrived at the outskirts of the city, it was suddenly colder again. There was snow that winter and also that night. We had only the clothes we were wearing, and my mother had her purse. In this one night, we had lost all of our earthly possessions. [28]

The Frenzels found a place to stay in Heroldsberg, where Brother Frenzel’s employer had erected some temporary barracks. According to Zenos, “the temporary structure consisted of two rooms, one about eighteen by eighteen and the other about eighteen by sixteen. We had no light, no water, no gas, no telephone, no toilet (just an outhouse), and no stove.” For the Frenzels, “temporary” became five years, but when so many people had lost their homes, their shack was a veritable blessing. The secret to their survival in the immediate aftermath of the war was the food supply that Hans Albert Frenzel had stored for his family at the home of his brother in Burgthann, some fifteen miles from Heroldsberg. Hans Albert made many trips there to retrieve some of the food for his family of six. They were all glad that Brother Frenzel had heeded the advice of the Church leaders to set aside food for bad times.

Willy Eysser recalled hearing that the Schröpf family (residents of the top floor of the building at Untere Talgasse 20 and members of the branch) were killed in their basement shelter on January 2. Apparently the bombs burst wine bottles and barrels of vinegar stored there, and the occupants of the shelter drowned in the ensuing chaos.

Following the destruction of the branch rooms, there was no building available to the branch until well after the war. Eyewitnesses still in the city in the spring of 1945 recall meeting in a school and in the apartments of surviving members, usually in groups of ten to twenty persons. Waltraud Weiss said that on several occasions, her father traveled across the city from their home in the eastern suburbs to visit the Fürth Branch to the west—a distance of six miles that took about two hours to negotiate.

Hermann Baer recalled seeing the ruins of the church building: “It was all burned out. The only thing left standing were the bare walls. There was nothing saved. After that, we met in a school for a while.” He had recalled seeing pictures of Jesus Christ and President Heber J. Grant on the walls of the meeting rooms before the building was destroyed, but it would be some time before such was the case again in the Nuremberg Branch.

Walter Schwemmer’s evacuated school class included boys who wanted nothing more than to go home in January 1945. The group had been away from Nuremberg for more than two years—first in Czechoslovakia and then in Rothenburg, Bavaria. Soon, several boys simply took off for home and actually made it safely there. Finally, the leaders relented and sent all of the boys home to Nuremberg.

In February 1945, Georg Strecker was drafted into the Wehrmacht. By war’s end, he was a POW, and his wife did not know his whereabouts for two years. He was in Marseilles, France, but Elisabetha’s letters to him through the French government were never delivered (nor were his to her). Finally, he decided to write to a friend in the United States, who wrote to his mother in Nuremberg. She was able to contact Elisabetha Strecker with the news that her husband was alive. She had left Nuremberg when her husband was drafted—following the recommendation of the government that she take her children to a safer location. She stayed on a farm near Hohenstadt until October of that year. [29]

“The war ended with the Americans coming in,” according to Walter Schwemmer:

We saw the tanks coming in and the soldiers walking down the street. They waved at us kids and threw candy. We weren’t afraid. . . . Those were the first Americans we had ever seen. There was no fighting. I remember learning in the Hitler Youth that they were our enemies. . . .We heard that the black soldiers would come and kill us, would cut our heads off or would do other terrible things to us. But in reality, they were the nicest ones to us. They were the ones to throw the candy and to smile and wave.

“As the Americans marched into our city, one can say that they were very humane,” recalled Marie Mördelmeyer. Her husband had returned to Nuremberg in May 1945 and soon found work with the occupation forces. Marie explained that “he worked at the ‘SS’ barracks [now occupied by the US troops] fixing the bathtubs and toilets and all the other things that were ruined during the war and during the takeover of the city. And it continued to get better.” [30] The Mördelmeyer family was indeed fortunate in many respects during the summer of 1945.

The invading Americans stopped long enough in the northern suburbs of Nuremberg to set up artillery near the Baer home. Young Hermann recalled how the GIs took possession of his home. The Baers moved into another apartment for the next two weeks, but Hermann was allowed to return to the house several times in order to retrieve food and other needed items. He was not happy with what he saw, recalling, “They would put their feet up on the dining room table, and I went in there and put a table cloth on it and told them not to put their feet up there. They did a little bit of damage but not that much.” However, what began as a relatively harmless situation nearly took a tragic turn. Some neighborhood boys informed the GIs that there were girls nearby, including Hermann’s sister. As he recalled:

One soldier came at night, and he brought us chocolate and stuff and then he wanted to take my sister up in the bedroom and rape her. He had a pistol. He set it down, and I picked it up and threatened him and said, “You’re not going upstairs.” My sister took off up the stairs, and my older sister stood in front of the door. [The GI] could speak a little German, and I told him, “If you’re going to push my sister around, I’m going to shoot you.” Then my mother went outside and yelled for an MP, and the GI got scared and left. . . . I think I would have shot him if he physically attacked my older sister.

Fig. 13. Survivors of the Nuremberg Branch in 1947. (L.BaerBonds)

Fig. 13. Survivors of the Nuremberg Branch in 1947. (L.BaerBonds)

When the fighting stopped in Czechoslovakia in the spring of 1945, Willy Eysser and his comrades found themselves trapped between the Americans advancing from the west and the Soviets from the east. Their captain instructed the men to load a vehicle with supplies and prepare to move toward the American lines. When a general came by and learned of the plan, he drew his pistol and threatened to shoot the men for desertion. Fortunately, the captain came by in time to convince the general of the wisdom of the plan. The men did indeed surrender to the Americans and became some of the twenty-four thousand German soldiers who became POWs under the Allied invaders at that location.

Fearing that they would be turned over to the Soviets, Willy Eysser was greatly relieved when he and a few thousand other POWs were told by their American captors in July 1945 “to hurry home, but watch out for the curfew restrictions,” as Willy recalled. He wasted no time in making his way home to Nuremberg, where an uncle informed him of the whereabouts of his parents. They had been bombed out of their home and were living on a farm a few miles from the city. Willy was able to find a place to stay amid the ruins of Nuremberg before the summer was out, and he joined perhaps twenty-five persons for church meetings there.

“When the war was over, we received a letter stating that my father had served as a fine soldier but that he was missing in action,” recalled Lorie Baer. “My mother nearly fainted and knew that if they wrote that, he was [most likely] dead somewhere. As soon as we got over the news, I remembered that my father had said that he was not going to go back to his unit, and I told my mother that.” As it turned out, Otto Baer had gone into hiding in Austria rather than to his unit on the Eastern Front. On his way home after the war ended, he was confronted by GIs who demanded to see his papers. He showed them his little book with the names and addresses of Americans with whom he had served as a missionary in the early 1930s. The GIs were impressed and sent him on toward Nuremberg, rather than take him prisoner.

“When the war was over, we could see practically from one end of Nuremberg to the other,” claimed Ferdinand Schwemmer. “That’s how bad the destruction in the city was.” Indeed, contemporary photographs show very few structures still standing within the old city walls.

Elisabeth Gentner had been living in Bamberg with her children since 1943. She had lost her husband in Russia in 1944 and was hoping for a calmer life by leaving Nuremberg. She and her children were told to stay in the basement when the American army approached Bamberg in April 1945. She had this recollection of her first encounter with the invaders:

We woke up the next morning not expecting anything, opened up the trap door [from the basement], and walked into our living room. American soldiers were sitting everywhere, and it was the first time for me that I saw a black person. We were not scared. [Some of] the first soldiers who entered our home were Mormons. They were very nice to us, and they started talking to us. We asked them where they were from, and when they answered that they were from Utah, we said that we had relatives living there. Then we found out that we were all members of the Church. We could all speak a little bit of each other’s languages.

The Gentners therefore had several reasons to be relieved that the war was over. Their conquerors were good people, and the violence of the past few years had finally ceased.

Brunhilde Baer, daughter of Ferdinand Abier and niece of Otto Baer, was born one week before the war began—just in time to experience the worst years of the twentieth century in Germany. “I remember wearing the same clothes every single day. They were washed on Fridays, and then we would wear them again for the rest of the week.” [31] Her family was bombed out and found a place to stay in the small town of Markt Erlbach, fifteen miles west of Nuremberg.

At first, it must have seemed nice to have a room in a farmhouse far from the ruins of her hometown, but Brunhilde recalled that the invading American soldiers moved into that room and relegated the Baers to the cellar:

The cellar was filled with potatoes and other food, and it was cold and wet. We lived down there for an entire year. It was so cold in the cellar, and there was no way to heat it—no stove or oven. We had lanterns down there because we didn’t have electricity. The Americans lived upstairs. They didn’t steal or take any of our property. But they didn’t respect our home either—they were pretty rough.

Brunhilde also recalled begging for food from local farmers. Her story is typical of the times:

One time, we didn’t have anything to eat, and I remember that we cried ourselves to sleep that night. Our stomachs hurt so much. We knelt down and said a prayer. Another member of the Church was also living in our town, and the next morning we found a basket with potatoes and mushrooms in front of our door. That was the moment in which I gained my testimony of prayer.

Fig. 14. Friedrich and MariaMördelmeyerwith their daughters Helga andAnnemarie. (H.MördelmeyerCampbell)

Fig. 14. Friedrich and MariaMördelmeyerwith their daughters Helga andAnnemarie. (H.MördelmeyerCampbell)

On April 17, 1948, Georg Strecker came home from his POW experience in France. Arriving in Nuremberg, he first hugged and kissed his sister-in-law, thinking that she was the wife he had not seen for three years. [32] His daughter Brigitte, by then ten years old, did not know at first what to call her father, “because he was gone so long. Everybody was an uncle to me. I called them uncle this and uncle that, even though they were strangers. So I said, ‘Should I call him “uncle” or “dad” or what?’ and they said, ‘Well, he’s your papa, so you call him “Papa.”’ I said, ‘Okay.’” [33] In all likelihood, a higher percentage of members of the Nuremberg Branch lost their homes and were forced to leave town than any other branch in Germany. They had been scattered all over the continent, and it would take literally years before the survivors could return. Neverthess, the few who were still in the city when World War II ended never ceased to hold meetings whenever or wherever possible. Their losses were great, but they did not attribute those losses to God. On the contrary, they believed that it was God who had preserved the survivors and the branch.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Nuremberg Branch did not survive World War II:

Ferdinand Johannes Bär b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 21 Oct 1908; son of Johannes Bär and Luise Pauline Weigand; bp. 18 Jun 1921; m. 1 Dec 1937; 4 children; k. in battle Russia 11 Aug 1943 or 1944 (Eysser Weiss-Burger; IGI)

Hildegard Ottilie Bär b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 7 Jul 1938; dau. of Ferdinand Johannes Bär and Ottilie Grill; d. diphtheria 31 Jul 1941 (CHL CR 375 8 2458; IGI)

Michael Baumgärtner b. Erlingshofen, Eichstädt, Mittelfranken, Bayern, 12 Sep 1873; son of Johannes Baumgärtner and Johanna Schwäbel; bp. 22 Jul 1907; conf. 22 Jul 1907; ord. teacher 31 Jul 1921; m. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 25 Oct 1897, Nanette Anna Barbara Specht; 1 child; 2m. Nürnberg 4 Aug 1924, Margarete König; d. stomach cancer Nürnberg 4 Oct 1942; bur. 7 Oct 1942 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 64; CHL CR 375 8 2458; IGI)

Johann Beierlein b. Rosenbach, Oberfranken, Bayern, 20 May 1870; son of Heinrich Beierlein and Anna Katharina Reusch; bp. 1 Jan 1909; conf. 3 Jan 1909; ord. teacher 1 Oct 1922; ord. priest 29 Jul 1928; ord. elder 10 Apr 1932; m. 8 Aug 1900, Marie Kathrina Glaser; 2 children; d. old age 21 Nov 1944 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 65; CHL CR 375 8 2458; FHL microfilm 25721, 1925 and 1930 censuses; IGI)

August Blum b. Ruppichteroth, Rheinland, 18 Mar 1860; son of Karl and Wilhelmine Blum; bp. 18 Jun 1921; conf. 18 Jun 1921; ord. deacon 7 May 1922; ord. teacher 30 Nov 1924; ord. priest 2 Jun 1929; ord. elder 24 Oct 1937; m. Friedrika-Karolina Gerner; d. old age 29 Oct or Nov 1940 (FHL Microfilm 68802, no. 76; CHL CR 375 8 2458; FHL microfilm 25725, 1925 and 1930 censuses; IGI)

Babette Senft or Brohmann b. Herbolzheim, Mittelfranken, Bayern, 10 Apr 1885; dau. of Anton Brohmann and Barbara Senft; bp. 8 Apr 1913; conf. 8 Apr 1913; m. 6 Jan 1906, Johann Weiss; d. diabetes 4 Jul 1944 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 171; CHL CR 375 8 2458; IGI)

Max Denerlein b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 27 Dec 1886; son of Johann Matthias Denerlein and Anna Babette Eder; bp. 26 Apr 1942; conf. 26 Apr 1942; ord. deacon 28 Feb 1943; m. 18 Sep 1920, Katherina Stengel; d. uraemia 25 Sep 1943 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 569; CHL CR 375 8 2458; IGI)

Johann Eysser b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 1 Jan 1919; son of Johann Wilhelm Eysser and Anna Kathrine Pfeiffer; bp. 3 Jun 1928; conf. 3 Jun 1928; ord. deacon 25 Mar 1934; ord. teacher 5 Apr 1937; ord. priest 10 Mar 1940; ord. elder 10 Nov 1941; infantry; k. in battle Fomino (possibly near Zwetowka), Russia, 12 Apr 1942 (Eysser; www.volksbund.de; IGI; FHL microfilm 68802, no. 277; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 10–12; FHL microfilm no. 25763, 1930 and 1935 censuses; www.volksbund.de)

Fig. 15. Hans Eysser. (W. Eysser)

Fig. 15. Hans Eysser. (W. Eysser)

Maria Fetzer b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 11 Nov 1881; dau. of Johann Jobst Fetzer and Margarete Brehm or Mauser; bp. 30 Dec 1923; conf. 30 Dec 1923; d. suicide 28 Mar or 20 Apr 1943 (CHL CR 375 8 2458; FHL microfilm 68802, no. 211; IGI)

Josua Helaman Albert Frenzel b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 12 Aug 1938; son of Hans Albert Frenzel and Frieda Babette Burkhardt; d. of diarrhea and sickness 17 Dec 1939 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 527; FHL microfilm 25769, 1935 census)

Georg Friedrich Gentner b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 24 Jan 1909; son of Hermann Guck and Frieda or Friederika Gentner; ord. deacon; m. Elisabeth Charlotte Schöpf; 3 children; noncommisioned officer; d. in Russia 1944 (Gentner; FHL microfilm 25773, 1935 census)

Friederika Gentner b. Regensburg, Oberpfalz, Bayern, 16 Jan 1891; dau. of Johann Gentner and Eva Hermann; bp. 30 Dec 1923; conf. 30 Dec 1923; m. Hermann Guck; 2 children; d. heart disease 8 Feb 1945 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 215; FHL microfilm 25779, 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Margarete Gentner b. Regensburg, Mittelfranken, Bayern, 18 Oct 1892; dau. of Johann Georg Gentner and Eva Herrmann; bp. 30 Dec 1923; conf. 30 Dec 1923; m. 25 May 1929, Andreas Mehringer; missing (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 216; FHL microfilm 245231, 1930 census; IGI)

Otto Gentner b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 3 Jun 1910; son of Hermann Guck and Friederika Gentner; bp. 30 Dec 1923; conf. 30 Dec 1923; m. 19 Nov 1935; sergeant; k. in air raid Paris, France, 29 Mar 1944; bur. Champigny-St. Andre, France (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 10–11; FHL microfilm 68802, no. 214; FHL microfilm 25773, 1930 census; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Hermann Hermann b. Weinau, Ebersdorf, Bautzen, Sachsen 10 Oct 1870; son of Joseph Hermann and Agnes Köhler; bp. 19 Sep 1905; conf. 19 Sep 1905; ord. priest 28 Feb 1915; ord. elder 30 Mar 1931; d. cardiac insufficiency 24 Jan 1940 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 101; FHL microfilm 162782, 1930 and 35 censuses; IGI)

Elisabeth Höhne b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 14 Oct 1866; dau. of Rudolf Höhne and Katharina Pabst; bp. 15 Sep 1901; m. —— Hirner; d. old age 10 Jul 1940 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 97)

Konrad Hofmann b. Birkenreuth, Oberfranken, Bayern, 8 Feb 1869; son of Johann Hofmann and Anna Modschiedler; bp. 10 Jun 1894; conf. 10 Jun 1894; ord. priest 3 May 1903; ord. elder 2 Apr 1933; d. old age 13 Mar 1944 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 98; CHL CR 375 8 2458; IGI)

Sophie Katherina Hofmann b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 28 Mar 1917; dau. of Karl Bernhardt Joseph Hofmann and Katherina Schmidt; d. bone disease 3 Mar 1942 (CHL CR 375 8 2458; IGI)

Kunigunde Horn b. Bayreuth, Oberfranken, Bayern, 23 Jan 1886; dau. of Wolfgang Horn and Katharina Hoffmann; bp. 25 May 1924; conf. 25 May 1924; m. Plauen, Zwickau, Sachsen, 18 May 1907, Richard Schöpf; 5 children; k. in air raid Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 2 Jan 1945 (Gentner; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 10–11; FHL microfilm 68802, no. 241; IGI)

Kurt Peter Josef Kormann b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 22 Feb 1925; son of Ernst Baptist Kormann and Maria Magdalena Baier; bp. 22 Jul 1933; conf. 22 Jul 1933; d. blood disease Nürnberg 10 Sep 1939 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 377; FHL microfilm 271381, 1935 census; IGI; PRF)

Anna Marie Lang b. Marktbergel, Unterfranken, Bayern, 3 Aug 1868, dau. of Leonhard Christoph Lang and Regina Barbara Reichert; bp. 31 Jul 1923; conf. 31 Jul 1923; m. 23 Feb 1891, Lorenz Gottlieb Hofmann; 5 children; d. stomach cancer Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 27 May 1942 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 196; CHL CR 375 8 2458; IGI, AF, PRF)

Karl Morgenroth b. Bamberg, Oberfranken, Bayern, 3 Apr 1923; son of Ludwig or Joseph Morgenroth and Marie Loerber or Lorber; bp. 20 Sep 1943; conf. 20 Sep 1943; m. Bamberg, Bayern, 15 or 19 Apr 1944, Barbara Melber; k. in battle Latvia 30 Oct 1944 (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 10–11; FHL microfilm 68802, no. 579; IGI)

Georg Alfred Popp b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 19 Dec 1924; son of Georg Popp and Anna Elisabeth Ulmer; bp. 4 Jan 1936; conf. 5 Jan 1936; ord. deacon 2 Apr 1939; corporal; d. of wounds Dnjepropetrowsk, Russia, 16 Sep 1943 (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 10–11; FHL microfilm 68802, no. 496; FHL microfilm 245255, 1935 census; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Babette Popp b. Fürth, Nürnberg, Bayern, 12 Oct 1879; dau. of Michael Popp and Margaretha Eder; bp. 29 Oct 1889; conf. 29 Oct 1889; m. 24 Dec 1900, Alexander Köstel; d. chronic rheumatism Bürnberg, Bayern, 20 Feb or 10 Jun 1945 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 239; FHL microfilm 271381, 1935 census; IGI)

Ellen Elsa Precht b. Bamberg, Oberfranken, Bayern, 15 Jul 1913; dau. of Johann Barnabas Sieghärtner and Gertraud Precht; bp. 15 Jul 1928; conf. 15 Jul 1928; m. Nürnberg, Mittelfranken, Bayern, 3 Nov 1936, Andreas Bundle; d. accident or endocarditis Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 1942 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 282; CHL CR 375 8 2458; IGI)

Joseph Rothmeyer b. Fürth, Nürnberg, Bayern, 8 Sep 1911; son of Anton Rothmeier and Franziska Bierl; d. of wounds Russia 20 Dec 1943 (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 10–11)

Margarete Sandhofer b. Neustadt, Mittelfranken, Bayern, 24 Jun 1861; dau. of —— Witt and Margarete Sandhofer; bp. 19 or 20 Sep 1905; m. Franz Sandhofer; 1 child; d. old age 5 Dec 1941 (CHL CR 375 8 2458; FHL microfilm 245257, 1935 census; IGI)

Johann Georg Schmidt b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 13 Sep 1888; son of Johann Schmidt and Anna Nannette Barbara Specht; bp. 27 Nov 1905; conf. 27 Nov 1905; ord. elder 17 Jul 1920; m. 10 Jun 1916, Frieda Katharina Sauer; 1 child; d. lung ailment Nürnberg 23 Jan 1942 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 131; CHL CR 375 8 2458; IGI; AF)

Kuno Schönstein b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 15 Oct 1912; son of Johann Schönstein and Margarete Amalie Mahr; bp. 30 Dec 1923; conf. 30 Dec 1923; ord. deacon 6 Jan 1929; m. Nürnberg 9 Apr 1936, Anna Katharina Reher; private; k. in battle Lyk, Ostpreußen, 19 Apr 1943; bur. Bartosze, Poland (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 10–11; FHL microfilm 68802, no. 220; FHL microfilm 245258, 1925 census; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Richard Schöpf b. Hirschberg/

Fig. 16. Kunigunde and Richard Schöpf with their grandchildren in about 1939. The Schöpfs were killed on January 2, 1945, in the air raid that destroyed the church rooms at Untere Talstrasse 20 and most of the downtown Nuremberg. (G. Gentner Kammerer)

Fig. 16. Kunigunde and Richard Schöpf with their grandchildren in about 1939. The Schöpfs were killed on January 2, 1945, in the air raid that destroyed the church rooms at Untere Talstrasse 20 and most of the downtown Nuremberg. (G. Gentner Kammerer)

Heinrich Schwemmer b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 29 Mar 1908; son of Johann Konrad Schwemmer and Elisabeth Scheitler; bp. 18 Nov 1918; conf. 18 Nov 1918; ord. deacon 10 Apr 1932; ord. teacher 25 Mar 1934; ord. priest 25 Dec 1938; m. 4 Apr 1930; 4 children; corporal; k. in battle H. V. Pl. Gaiduk (probably near Noworossijsk, Russia) 15 Oct 1942 (Eysser; www.volksbund.de; IGI; FHL microfilm 68802, no. 409; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 10–11)

Konrad Schwemmer b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 10 Apr 1917; son of Johann Konrad Schwemmer and Elisabeth Scheitler; bp. 24 Apr 1925; ord. deacon 11 Oct 1931; ord. teacher 4 Apr 1937; m. Olga Maria Weigand; private; d. in POW camp near Daugawpils, Latvia, 16 Jun 1945; bur. Daugavpils, Latvia (Eysser; CHL CR 275 8 2458, p. 446; FHL microfilm 68802, no. 152; FHL microfilm 245259, 1935 census; www.volksbund.de)

Elisabeth Walter b. Gottmannsdorf, Heilsbronn, Mittelfranken, Bayern, 21 Jun 1912; dau. of Georg Leonhard Walter and Anna Elise Dürsch; bp. 3 Oct 1922; conf. 3 Oct 1922; m. 6 Jul 1935, Wilhelm Nicklas; d. lung disease 4 Oct 1940 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 181; FHL microfilm 245293, 1930 and 1935 censuses)

Pauline Weigand b. Nordheim, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 17 Jun 1869; dau. of Otto Weigand and Luise Stoll; bp. 5 Jul 1902; conf. 5 Jul 1902; m. —— Bär; 3 children; d. old age 30 May 1943 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 61; CHL CR 375 8 2458; FHL microfilm 25715; IGI)

Anna Wendler b. Lauf, Entmersberg, Mittelfranken, Bayern, 25 Mar 1854; dau. of Andreas Wendler and Katherina Wittmann; bp. 31 Jul 1919; conf. 31 Jul 1919; d. old age 3 Mar 1945 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 162; FHL microfilm 245296, 1930 and 1935 census; IGI)

Karoline Betty Willeitner b. Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Bayern, 18 Feb 1928; dau. of Ludwig Willeitner and Agnes Barbara Lindner; bp. 23 May 1936; conf. 23 May 1936; d. heart ailment 5 Oct 1944 (FHL microfilm 68802, no. 274; CHL CR 375 8 2458; IGI)

Notes

[1] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[2] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CR 4 12.

[3] Nuremberg city archive.

[4] Der Stern, 1939, 386.

[5] Wilhelm Eysser, interview by the author in German, Salt Lake City, March 10, 2006; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[6] Gerda Gentner Kammerer, interview by the author in German, Bamberg, Germany, August 13, 2006.

[7] Waltraud Weiss Burger, interview by the author in German, Erlangen, Germany, May 27, 2007.

[8] Helmut Schwemmer, “Memories and Reminiscences, vol. I” (unpublished manuscript, 1998), 7.

[9] Schwemmer, “Memories,” 7.

[10] Lorie Baer Bonds, interview by Michael Corley, Provo, UT, March 6, 2008.

[11] Walter Schwemmer, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, August 21, 2009.

[12] Elisabetha Eva Baier Strecker, autobiography (unpublished, 1992), 6.

[13] For more about Paul Eysser, see the story of the Worms Branch in the Karlsruhe District.

[14] Marie Strecker Mördelmeyer, “My Life Story” (unpublished autobiography, 1978), 3.

[15] Helga Mördelmeyer Campbell, interview by the author, Provo, UT, May 28, 2009.

[16] Oswald Schwemmer, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, July 10, 2009.

[17] Hermann Baer, telephone interview with the author, August 6, 2009.

[18] Heinrich Schwemmer to Elisabeth Scheitler Schwemmer, October 4, 1942. Used with the kind permission of Walter Schwemmer. Heinrich’s younger brother, Konrad, died as a POW in June 1945.

[19] Baier Strecker, autobiography, 6.

[20] Strecker Mördelmeyer, autobiography, 5.

[21] Annamarie Mördelmeyer Stauber, telephone interview with the author in German, August 6, 2009.

[22] Benjamin Frenzel, telephone interview with the author, April 6, 2009.

[23] Schwemmer, “Memories,” 2.

[24] Brigitte Strecker Burns, interview by the author, Park City, UT, June 25, 2009.

[25] During the final years of the war, air-raid wardens in some cities refused to allow Jews and foreign workers (and other “undesirables”) to take refuge in public shelters. Experts estimate that only about 20 percent of the residents of cities could be accommodated in concrete bunkers. In rural communities, such shelters were unknown.

[26] Ferdinand Schwemmer, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, August 21, 2009.

[27] The city prison is located on Fürtherstrasse and served as the venue for the Trial of German Major War Criminals, or the Nuremberg Trials, in 1945–46.

[28] Zenos Frenzel, interview by the author in German, Bountiful, Utah, June 25, 2009.

[29] Baier Strecker, autobiography, 7.

[30] Strecker Mördelmeyer, autobiography, 3.

[31] Brunhilde Baer Schwemmer, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, August 21, 2009.

[32] Baier Strecker, 7.

[33] The term Onkel is still used in German today (mostly by little children) to denote not only an actual uncle but also any adult male who is a good friend of the family. Brigitte’s confusion on that occasion was predictable.