Mannheim Branch

Roger P. Minert, “ Mannheim Branch, Karlsruhe District,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 236–49.

The city of Mannheim is situated on the east bank of the Rhine River at the northern extent of the old province of Baden. The Neckar River flows along the city’s northern border into the Rhine. The city was home to 280,365 people in the summer of 1939, only 121 of whom were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In fact, the percentage of Church members among the city’s residents was even smaller because some members of the Mannheim Branch lived across the river in Ludwigshafen, a city half the size of Mannheim. Ludwigshafen had enjoyed its own branch in the 1920s, but emigration had caused its demise. The members living there rode the streetcar across the Rhine to Mannheim to participate in meetings and branch activities.

The status of the leaders of the Mannheim Branch in the summer of 1939 is somewhat unclear. Reed Oldroyd, a missionary from the United States, was serving as the branch president. Despite the fact that the mission statistics show five elders and twelve Aaronic Priesthood holders as members of the branch, none are listed as counselors or secretaries to Elder Oldroyd. [1] Johann Martin Scholl, who had been the branch president for decades beginning in 1902, was still present and serving as the leader of the Sunday School. With the departure of the American missionaries on August 26, 1939, Brother Scholl likely was called to preside over the branch.

| Mannheim Branch [2] | 1939 |

| Elders | 5 |

| Priests | 6 |

| Teachers | 4 |

| Deacons | 2 |

| Other Adult Males | 33 |

| Adult Females | 55 |

| Male Children | 7 |

| Female Children | 9 |

| Total | 121 |

When the war broke out on September 1, 1939, the Mannheim Branch was meeting in rented rooms at D2–5. In the unique numbering system used in Mannhei, this notation means building number 5 on block D2, just a few hundred yards from the city’s center. [3] The branch rented rooms in a Hinterhaus at that location. According to Elfriede Deininger (born 1921), “It was a large room connected to three smaller rooms on the side. There were about sixty members [attending].” [4] The meeting schedule included Sunday School at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting at 4:00 p.m. Mutual was held on Tuesdays at 8:00 p.m., and the Primary and Relief Society meetings were held on Wednesdays at 3:30 and 8:00 p.m. respectively.

Gottfried Leyer (born 1927) recalled making the long trek from his home in a suburb of Mannheim north of the Neckar River downtown to church. “It took about an hour to walk to church and it was too far to go home for lunch and back for sacrament meeting, so we stayed in the church rooms or went with friends to their homes between meetings.” [5]

Fig. 1. Youth of the Mannheim Branch in 1939. (L. Deininger Harrer)

Fig. 1. Youth of the Mannheim Branch in 1939. (L. Deininger Harrer)

Walter E. Scoville of the United States had served in the West German Mission before the war and kept up his correspondence with several families of the Karlsruhe District. He received the following letter from Elfriede Deininger of the Mannheim Branch dated March 6, 1940:

It was such a nice time while you were here [in 1939]. Things have changed since then. It’s really lonely around here. The men are all in the army and we women and children have lots of work. We are still holding meetings, but for how long? And our dear Father Scholl died [29 Feb 1940, age 78]. We held his funeral yesterday. This is a terrible loss for each of us, for the entire branch. The only men left are Brother Dönig, Brother Ziegler, and Andreas Leyer (but he is leaving soon). . . . Helene, Kläre, and I will also be leaving in the fall. We have to serve our “duty year” and this year they are calling up the girls born in 1920–1921 so the three of us have to be ready to leave. We are looking forward to this time when we too can serve Germany. The day before he died, Brother Scholl said to us, “Hitler will lead Germany to a marvelous and lasting peace and victory, even if it takes years. Every German is of this opinion nowadays. Actually, it is not an opinion but a sincere belief. We believe that God is with him, or else he would not have been able to accomplish such great things in the past and the present. And we know that God will be with our Führer in the future as well. The greater the pressure from foreign nations, the tighter the bond between our Führer and the people. No power on earth can break that bond, not even the English. Conditions in the branch are still very good, but we are short on priesthood holders. [6]

Spirits were high in Germany at the time. The Polish campaign had lasted less than a month, and Germany’s enemies had not yet attacked. It appeared indeed as if Germany would be victorious. Although Elfriede’s letter suggests that all of the members of the Mannheim Branch were convinced of Hitler’s good standing with God, this certainly cannot be said about the German Latter-day Saints in general, as is clear from many eyewitness reports. The letter was written two months before the German army invaded France and before air raids on German cities became frequent and deadly.

Elfriede Deininger was a young woman dedicated to the Church. She later wrote of the problems in the branch after the priesthood holders left: “It was a lonely feeling to have no priesthood holders in our midst. But even with our men gone we could still have a prayer.”[7] In her personal life, things were looking up in 1940 when she began dating Horst Prison, a soldier from the Saarbrücken Branch. He wrote her often from the Eastern Front, where he went through very difficult trials for the next three years.

Manfred Zapf (born 1930) was inducted into the Jungvolk through his school when he turned ten years of age:

We had uniforms, and I attended the meetings. In a way, it was just like the Boy Scouts, so we enjoyed it. We played little games, like war games, and for Christmas we made toys for other children. We also marched around and did service projects. But really we were just kids and enjoyed being together. Sometimes my father would write an excuse because I had to help in the garden, but I never got into trouble [for missing meetings]. [8]

“The first bombing of Mannheim was in about September 1941,” recalled Gottfried Leyer. “Mannheim had a big airfield for fighter planes. When the first bomb came down on this one Sunday, all the people living nearby went out to see [where it landed]. I can picture it there, between houses, right in the garden, a big crater. That was probably the first bomb that fell on Mannheim.”

Regarding the air-raid shelters available to city residents, Manfred Hechtle (born 1928) provided this description:

The basements were made in such a way that they had a large room there where people could gather. And then, since apartment houses have one common firewall between them, it was required that they be broken through in the basement from one to another so that if something happened on one side, people could go through and to the [adjacent] basement. It could go for a whole block that way. But they bricked it back up. The bricks were set sideways, so then a sledgehammer was set next to it so it could easily be broken through.

Ludwig Harrer married Lina Deininger and was drafted soon after the war started. In February 1942, he came home on leave and told his sister-in-law Elfriede that he had disobeyed an order and was being punished; he had captured two black French soldiers and was commanded to execute them rather than to guard them as prisoners of war with the usual rights. He had refused to carry out the order and was punished with a transfer to the Eastern Front. He told Elfriede that he would soon join her deceased mother. Two weeks later he was killed in Russia. [9]

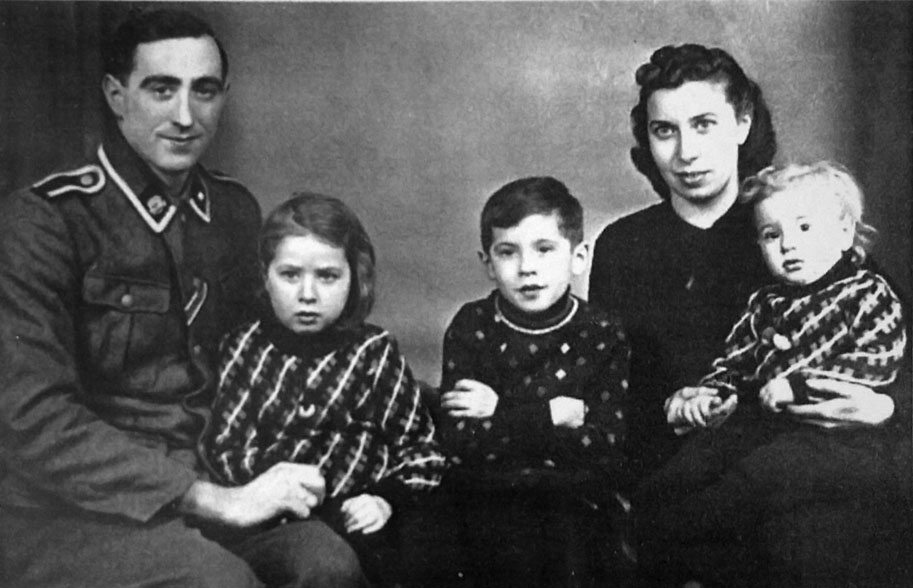

Fig. 2. The family of Ludwig and Lina Harrer in 1941. (L. Deininger Harrer)

Fig. 2. The family of Ludwig and Lina Harrer in 1941. (L. Deininger Harrer)

Manfred Hechtle had been a member of the Jungvolk since the age of ten and advanced to the Hitler Youth when he became fourteen. He recalled that although his participation was required, he was given the choice of various kinds of activities, and he chose the air force training program: “I started out learning how to fly a glider. We practiced with the glider on the ground, learning how to keep it level and land it straight. We did this on a grassy meadow.” [10]

As air raids caused increasing destruction in the city, the situation with schools became more challenging, as Manfred recalled:

The school that I went to was only a block away from where I lived. In those days, of course, half of the school was for girls and half for boys. And they were physically separated in the building. My school was hit one night by [incendiary] bombs; the fourth [top] floor was actually eliminated. It was not in use anymore, but they put a roof over fast enough to continue school, so we were only off or transferred for a few weeks and then went back in.

According to Gottfried Leyer, “They had to combine classes; sometimes we had three classes combined as one. We didn’t learn much.” Manfred Hechtle indicated that younger teachers were replaced by older ones as the war dragged on and the amount of National Socialist propaganda preached by the teachers diminished.

Although air raids were frightful experiences, life went on afterward (as long as one’s home was intact), and children found ways to entertain themselves. Gottfried recounted how he and his friends went out right after the all-clear siren to search for metal fragments lying in the streets. The larger ones were from enemy bombs and the small pieces from local antiaircraft fire. “Once I found one that was still hot because we went outside right away.”

“I was an adventuresome kind of person,” Ralf Hechtle (born 1929) explained:

To me, an air raid was a great adventure where everybody ran to the shelters. I had to stand outside and watch. . . . In fact, once I saw an airplane that was shot down and barely missed hitting a house. It was coming down, and the sad thing was this: as it crossed the Neckar River I guess all the guys tried to jump out, but because the plane was so low they couldn’t use their parachutes and they all ended up dead on the beach on the other side. I didn’t actually see it crash, but I went right over there and saw it right after and saw the dead soldiers laying there. It was a big bomber. [11]

Manfred Hechtle recalled having regular youth activities in and around Mannheim until the middle of the war: “We met with young people from around the mission in the forests once or twice a year. Sometimes we went to a castle nearby. But as the war progressed, it became practically impossible to have any gatherings out of town. People were too nervous.” Much of his free time was spent with his younger brother, Ralph, and his LDS friends, Gottfried Leyer and Manfred Zapf, “until about 1943 when things went topsy-turvy.”

Fig. 3. The youth of the Mannheim Branch in 1942. (R. Hechtle)

Fig. 3. The youth of the Mannheim Branch in 1942. (R. Hechtle)

The program of evacuating children from high-risk cities was popular in Mannheim, as Manfred Zapf recalled:

We went to the countryside just as everybody else did. My parents had to stay in the city while my brother and I were sent away. We got little cards with our names on them that we hung around our necks [indicating our destination] and we were sent to Kenzingen, near Switzerland. We stayed with a very nice family; the father was the chief surgeon in the Kenzingen hospital. We stayed in the building in which his maids also stayed. It was close to the actual home, though. We did not know that family at all before we got there. [The government] just sent us there. I was very happy there because we had so many wonderful opportunities. I felt like a little king. My brother returned to Mannheim early because he had to attend high school, which was not available in Kenzingen.

Life in Mannheim in 1943 was becoming increasingly challenging for Elfriede Deininger, who described the situation in these words:

I was working all day for a company, assembling small electrical motors, and at the same time I was a firefighter. As soon as we heard the alarm we had to change clothes and be ready to go out. We never knew which direction the air raids would come from. We would hear the sound of the falling bombs, then the building would shake and smoke would fill the air. We found whole housing blocks on fire. Some houses would remain standing, so we had to spray the water on the burning places of those houses. The people in the basements, can you imagine? They died when the scalding water came down on them. As buildings collapsed, people were crushed. . . . The constant bombing frazzled our nerves, our spirits, and left us exhausted. [12]

Ralf Hechtle remembered that the frequency of air-raid alarms without attacks was so great that it became a burden to go downstairs to the shelter. He was simply too tired to get out of bed each time (even though a friend had been killed in the basement of the building just across the street). “I think my mother got gray hair worrying about me during alarms. . . . One time in particular I remember I got to the top of the stairs in the cellar, where you go [down] to the cellar and a bomb hit just in the next block. And it just lifted me up and threw me all the way down the stairs, and I hit a chair at the bottom.”

Fig. 4. Mannheim Latter-day Saints during the war.

Fig. 4. Mannheim Latter-day Saints during the war.

Horst Prison was granted leave in January 1944, and he went to Mannheim to marry Elfriede Deininger. As she explained, “In preparation for our wedding day my sisters Paula and Helen obtained extra food stamps and were able to cook a nice dinner and make a cake. That evening the sirens went off, and we had to go to a bomb shelter.” [13] The next day, they made the trip to Saarbrücken, where mission leader Anton Huck performed a wedding ceremony and ordained Horst an elder. Within days, he returned to duty on the Eastern Front.

As pleased as Elfriede was to be married, her trials soon became much worse. She saw Horst in France a few months later and had the premonition that they would not be together again for a long time. She was pregnant, but after the day in August when she received word that Horst was missing in action, she did not feel the baby moving any more. A woman doctor confirmed her suspicion that the baby had died, and the discussion that followed became intense, as Elfriede recalled:

The doctor was insolent: “There is no hospital open for you, but there is a midwife nearby who has a private clinic, and in an emergency I will come down, but you will have to pay in advance, for I doubt you will pull through.” I was furious. I screamed at her, “If I have to die like an animal, so be it, but you dirty pig, you will not get my money!” [14]

The child was delivered stillborn two days later—a boy weighing six and one-half pounds. “During my recovery it was hard for me to watch the new mothers as they nursed their babies,” Elfriede recalled. A crisis of faith ensued, but a friend from church explained an important principle to the heartbroken mother, who was wondering why God would let her child die: “Elfriede, that little word ‘why’ is the biggest tool in the devil’s workshop. God loves you and will comfort you if you will let him. He knows ‘why’ and all about your heartache, but it is best for you. Someday you will understand.” [15]

Manfred Zapf was still only fourteen years old and a member of the Hitler Youth when he came very close to the war in 1944, as he recalled:

I was sent to France to help out with the military—for example [servicing] tanks. I remember that I stayed there for a little over a year and that we had to sleep on concrete with just a bit of straw underneath and it was the middle of winter. The regular soldiers did not like us and wanted us to leave. We were too young for them and they had to watch us on top of everything else. Some of us were injured and that placed a greater burden on the soldiers. Some of my friends even got killed while we were there. It was a dangerous place to be. We eventually walked home from France—all the way back to Kenzingen. [16] We were able to travel in a vehicle only part of the way home.

The Hechtle family lost their apartment twice. The first one was located at Augartenstrasse 39 (east of the downtown) and the second on block S6. “There we had an underground bunker across the street,” Manfred Hechtle explained. Not every bomb that fell on an apartment house during the war meant destruction. Manfred recalled how the Hitler Youth boys were trained to nullify the effect of an incendiary bomb. “We had to keep a bucket of water and sand in the attic so that we could [smother] the bomb. We actually did that once when we found an incendiary bomb stuck between the attic and the top floor [of the building]. It had just barely ignited. We always had somebody there standing guard.”

Fig. 5. The ruins of the Hechtle apartment in 1943. (R. Hechtle)

Fig. 5. The ruins of the Hechtle apartment in 1943. (R. Hechtle)

On the day when the second Hechtle apartment building was struck by incendiary bombs, Ralf had an unforgettable experience. He had delayed seeking shelter when the attack began, and it nearly cost him his life:

I looked up and saw countless airplanes up in the sky. And so I figured I’d better run to the shelter, because I was closer to the shelter than I was to my house. And so I ran, . . . and I could hear the bombs coming down, whistling like crazy. And [the air pressure] knocked me down and something hit me across the back, and I thought, “I’m gonna die here.” And I looked up and I saw all these buildings collapsing around and fires starting, and I realized that I was hit by a branch of the tree which was lying by me. Through experience, I knew that the firebombs would [be dropped] after the big explosive bombs would come down. Because they’re lighter, they take longer to come down. [The enemy] just dropped them like matchsticks. And I knew I had to get out of there, because they’d just drop everywhere. And people had been hit by those things and burned to death. So I ran to the entrance of the shelter, and of course, they would not open the shelter during an attack. So I was standing there in the front of the door, and I watched all these firebombs drop. And as I looked across the street, I saw our house on fire.

After finishing public school, Ralf began an apprenticeship in a pastry shop. His work had interesting but unsettling aspects to it:

My boss owned the building, and our shop was in the basement. Every time there was an attack, the shingles got destroyed on top of the roof, and he sent me up to reshingle—on top of a six-story building. I was fourteen years old. Well, I couldn’t go up there and look down or I’d fall off. At first it didn’t seem to bother me, but I got kind of disgusted with him after a while, and I said, “I’m here to learn the trade, and I don’t want to be a roofer!”

Fig. 6. Andreas Leyer died of wounds suffered in Lithuania in August 1944. (G. Leyer)

Fig. 6. Andreas Leyer died of wounds suffered in Lithuania in August 1944. (G. Leyer)

In Gottfried Leyer’s neighborhood on the outskirts of town, the situation was different. They lived in a two-family home that did not have indoor plumbing. “We kept four or five buckets of water lined up by the pump.” One night an incendiary bomb struck the house and began to burn. Emerging from their hiding place in the basement, family members were able to extinguish the flames before too much damage was done.

Gottfried was drafted into the Wehrmacht at the age of sixteen. There was no longer time for service in the Reichsarbeitsdienst in those days; the army needed soldiers. Trained to serve at an antiaircraft battery, he was stationed near several cities in Germany and even in France for a few months. He was fortunate never to carry a gun or be involved in combat on the ground. When the Allies invaded Germany, Gottfried was in no real danger.

When Manfred Hechtle was still sixteen, he began training to become a pilot in the Luftwaffe and was sent to a small town northwest of Frankfurt. His training did not include flying, because airplanes were a rarity in Germany in the last year of the war. “We had more pilots than airplanes. They would draw lots to see who would fly. You can imagine what happened. They would go up and shoot down three planes and then be shot down themselves. A lot of them didn’t come back.” Eventually there was no fuel to fly the few airplanes left. Manfred was just barely tall enough to qualify for pilot training, but he never left the ground. Eventually, he was sent home, and the war ended before he could be given another assignment.

The general minutes of the Mannheim Branch illustrate the challenges faced by the members in the last eighteen months of the war: [17]

January 30, 1944: Karl Josef Fetsch [of Bühl, currently working in Ludwigshafen] was sustained as the branch president. Paul Prison [of Saarbrücken] was called as district president.

March 1, 1944: Air raids destroyed the home of the branch president and the branch meeting rooms; all church property and all records were destroyed. A new minutes book was started by Elder Karl Josef Fetsch. All possible records will be restored in this book. Meetings were held in the home of Sister Lina Harrer on Kappelerstrasse. Her home was also destroyed, so no meetings were held for a while. Then meetings began again in the home of Sister Luise Vokt at Ludwig Jolly Strasse 67.

March 12, 1944: Georg Dönig, officially branch president, returned from the war severely wounded and decided to go to his wife’s home in Grossgartach, Württemberg and thus joined the branch in Heilbronn.

April 22–23, 1944: Ten Saints from Mannheim attended the district conference in Karlsruhe.

December 10, 1944: Meetings were cancelled due to air-raid alarms. Two weeks later, meetings were again canceled.

January 6, 1945: Attacks damaged the downtown severely; no members were killed but some have slight property damage.

January 14, 1945: Meetings were canceled again.

January 21, 1945: More attacks, but no major damage among members. Meetings were canceled.

February 18, 1945: The two worst attacks of the war happened today. Again the members suffered little damage and none were killed. Again the Lord has preserved their lives. Average attendance on recent Sundays is twelve.

March 1, 1945: The worst attack of the war hits Mannheim and Ludwigshafen. The entire city is on fire. The Hechtles lose their home for the second time, but a few days later the Lord provides them a nice new place to live in Feudenheim at Talstrasse 67. The rest of the Saints (as far as we know) do not suffer any substantial damage.

March 4, 1945: Meetings are canceled.

March 22–29, 1945: There is fighting in Mannheim; American troops occupied the city. Those members who stayed in the city survived the fighting.

April 15, 1945: Today we were able to hold the first meetings again.

In March 1945, Elfriede Deininger Prison was living with her parents-in-law in a town near Stuttgart. One day, they noticed enemy troops coming toward the house. “They wore gray-green corduroy coats, a hood, and turbans on their heads. . . . We retreated from the windows, too frightened to say anything. We told the children to quietly pray for the Lord’s protection.” The soldiers were either Algerians or Moroccans serving under French command and were feared by German civilians. Elfriede had already heard stories about atrocities committed by those troops in neighboring villages.

Fig. 7. The city of Ludwigshafen was included within the Mannheim Branch. Because of its critical chemical industry (BASF), the city was under attack at least 125 times. Huge bunkers such as these were constructed to protect the citizens, but more than 1,800 people (including several Saints) were killed. [18] (R. Minert, 1971)

Fig. 7. The city of Ludwigshafen was included within the Mannheim Branch. Because of its critical chemical industry (BASF), the city was under attack at least 125 times. Huge bunkers such as these were constructed to protect the citizens, but more than 1,800 people (including several Saints) were killed. [18] (R. Minert, 1971)

The next day, an enemy soldier entered the Prisons’ house, and the situation was instantly tense. Fortunately, he was not searching for victims but rather for somebody to wash his clothes. Without speaking German, he made it clear that the women of that house were to feed his men and wash for them. Soon, he brought them food, and he and his four Moroccan comrades ate their meals with the household. His name was Rachau, and Elfriede’s family was safe with him around. [19]

When American tanks rolled into what was left of Mannheim, they fired a few shots, but little resistance was offered, and it was soon calm. The Hechtles had managed to find an apartment in a suburb of Mannheim called Feudenheim. When American soldiers came looking for housing, the Hechtles and many of their neighbors were evicted and not allowed to take anything with them. They spent the next two days at a lumberyard owned by their landlady. As Ralf recalled, the landlady—a beautiful young woman—was able to “charm” the Americans into letting the Hechtles return to their apartment.

According to Manfred, “[the GIs] liked to make friends and stand around talking, but in the evenings we weren’t allowed to look out the window or we would be shot.” As in all other occupied areas of Germany, curfew regulations were strictly enforced in Mannheim.

Just before the Americans arrived in Mannheim, Manfred Zapf and his mother had decided to go to Epfenbach (about twenty miles to the east and far from large cities).

We had a little cottage in that town from which my father came. While we were on our way, it was just our luck that an air raid would happen. There were no German soldiers around anymore and nothing else to shoot at, so the [pilots] used us as target practice. Two fighter planes were chasing us around a big oak tree, and the tree was so thick that the bullets did not go through it. They were also in each other’s way and had to be really careful not to fly into each other.

Manfred and his mother returned to Mannheim soon after this incident. Despite the fact that their home in the suburb of Käfertal was very close to several large industries, the building had suffered no more damage than a few broken windows during several attacks on those factories.

The end of the war for Ralf Hechtle was certainly enough to satisfy this adventuresome boy. Shortly before the Americans arrived at the end of March, he had been persuaded by a friend to see what items local German antiaircraft crews had left behind when they abandoned their positions.

So we went to the outskirts of town. And we took our wagons and found all kinds of stuff in those antiaircraft batteries—typewriters, phonographs, rifles, hand grenades—and we loaded our wagons. As teenagers we thought that was pretty cool. . . . We put a blanket over the wagon and pulled it home. Just as I got to the corner near where we lived, I saw a tank coming up the street. I didn’t pay that close attention, thinking, “Well, they’re Germans.” And pretty soon some soldiers came up with their ambulance, and they weren’t Germans! I looked a little closer, and there was a [white] star on the tank, and I said, “Uh-oh.” So [a GI] told me to stop, and he wanted to know what I had in my wagon. Well, he threw the blanket off, and there was all this stuff. He started throwing the things into an empty lot next to us. So I thought I’d help him. I picked up a hand grenade, and when he turned around and saw me, I thought he was going to shoot me right then. I was just thinking I’d help him unload the wagon.

Fig. 8. It is hard to imagine that in 1945 Ralf Hechtle looked old enough to be mistaken for a soldier. (R. Hechtle)

Fig. 8. It is hard to imagine that in 1945 Ralf Hechtle looked old enough to be mistaken for a soldier. (R. Hechtle)

The next thing he knew, Ralf was a prisoner of war, pushed onto a truck with German soldiers headed west. For three days, the truck wandered around with no apparent goal, and during that time the men were given nothing to eat. Finally, they were unloaded at what appeared to be a construction site near the city of Kaiserslautern. They had no roof overhead, and it was cold and wet, but at least they were given some K-rations to eat. It was there that Ralf met a boy who was sixteen and also should not have been treated as a POW. The two were young but understood that they might be handed over to the French; that could only be a bad development, so they devised a plan to escape. At one end of the compound was a brick wall separating the camp from another camp that housed civilians. The boys scaled the wall, mingled among the civilians, and then found a way out of the camp. Unfortunately, they were caught that evening—not knowing about the new curfew regulations. This time they were not treated as soldiers but rather as civilians who had violated curfew. Locked up in the police station, Ralf finally had a decent place to sleep—on a bench. The next day he was interrogated, and his future looked a bit brighter, as he recalled:

The American officer asked me if I knew the Boy Scout Oath. I recited it to him, and he said: “I’ll give you a pass that’s good for twenty-four hours. You’ll have to make it home in twenty-four hours.” And he gave me a package of gum and a little candy bar and sent me on my way. I was in my aunt’s riding boots that had high heels. I had twenty miles to walk in twenty-four hours, because there was absolutely no transportation. And he told me, “American vehicles will not pick you up; they’re not permitted to pick up anybody.”

Along the way, Ralf spent a short night in a barn, and then moved on toward the Rhine. French soldiers detained him for a while, suggesting that his papers were not valid, but finally allowed him to pass. When he reached the Rhine, the only way to cross was on a pontoon bridge constructed by the Americans, but they refused to let him do so.

I retreated a little ways and looked across the river. I said to myself, “Well, it’s too cold to swim that river.” (I’d done it before, but it was too cold at this time of year). And so I was praying and praying, and all of a sudden I was moved to walk. And I walked, and then a truck went across the bridge, and I walked behind that truck and nobody saw me—it was like I was invisible. Nobody said anything.

A few minutes later, he reached his home—barely within the time limit. His mother was thrilled to see him, having had no idea of his whereabouts.

When the war ended, Gottfried Leyer avoided becoming a POW. He was only seventeen and looked young for his age. Before the invaders arrived, he found some civilian clothing and volunteered to work for a farmer. The enemy soldiers moving farther into Germany paid him no mind. He remained on the farm for several months and then began working his way back toward Mannheim. “We would stop in at a farm and offer to work for a while, sleep there, and get something to eat. Then we would move on again. That’s how we worked our way home.” He was back in Mannheim toward the end of the summer of 1945.

For Elfriede Deininger Prison, the war would not truly end until Horst came home, but she returned to Mannheim in the summer of 1945. She described the conditions there in these words:

The city had nearly been destroyed, but I found my sisters alive and well. It took considerable time, but slowly life began to return to normal. Our branch was reorganized, and some of our brethren returned, so we had the priesthood in our midst again. Some of the men had been killed in the war. All those bitter years brought us closer together. [20]

One Sunday, an American soldier knocked on the door of Sister Vokt’s apartment, where the Saints had gathered. He had been a missionary in Mannheim before the war and wanted to determine the condition of the branch members there. The reunion was a joyous one, and a spirit of love and peace prevailed. According to Elfriede, “My anger at the Americans for bombing us disappeared in that meeting.” [21]

The general minutes of the branch read as follows on June 4, 1945:

Elder Eugen Hechtle [again district president] met with Major Warner, the representative of the [American] military government for church and educational affairs, and was treated very correctly. He was given two signs to be posted at the homes of Sister Vokt and the Hechtle family (where meetings are held), reading “Off limits to military personnel by order of the commanding general.” Major Warner promised us all possible assistance and expressed his hope that the church may soon conduct all of its activities again. Because we have no contact with the mission office, he promised to establish contact for us there. He also requested that we report to him every month regarding our activities, our progress and our finances. [22]

Fig. 9. Max Ziegler (shown here as a civilian in 1942) was one of several young men of the Mannheim Branch to die as soldiers.

Fig. 9. Max Ziegler (shown here as a civilian in 1942) was one of several young men of the Mannheim Branch to die as soldiers.

Fig. 10. Surviving Mannheim Branch members in 1945. (R. Hechtle)

Fig. 10. Surviving Mannheim Branch members in 1945. (R. Hechtle)

Former missionary Walter E. Scoville worked hard to establish contact with Latter-day Saints in Germany after the war. He received this response to a letter to Helene Deininger of the Mannheim Branch on January 30, 1947; she offered a summary of the war’s effect on the branch:

In the beginning, it was terrible for us to think about being at war, and we hoped that it would end soon. But we learned little by little to deal with it and to be patient. . . . Before he died in 1941, I used to pick up old Brother Scholl and walk with him to church and back. He had a little lantern and it was too dangerous for him to go alone during blackouts. . . . My own dear mother died a year after him. . . . She had a terrible kidney disease and wished to be relieved of her sufferings through death. . . . But she comforted us and encouraged us to remain faithful to the Church. . . . I would like to tell you about our experiences during the war. I would like to avoid the very sad things, but I really can’t do that, because there were sad events. My sister, [Lina] Harrer, lost her husband and her home. I lived with her at the time. Elfriede [Deininger] married and her husband was missing in action in Russia for two years. Last year we were thrilled when she finally heard from him. They have been writing each other often and she hopes that he will return soon. . . . Paula has been waiting for five years for her fiancé to return. . . . After the first few air raids, we lost our beautiful meeting rooms at D4 [sic]. The sisters in the branch had to leave town with their little children and the brethren had to serve in the military. We could only meet on Sundays. There were only a few of us. We first met in the home of Sister Harrer, but she was bombed out so we met in Sister Vokt’s home. . . . Life was hard but we enjoyed our church meetings. We often had to walk there because the streetcars were not running. . . . It took about 1½ hours each way. We really miss dear Brother Ziegler. We last heard from him just before the war ended. I still believe that he is alive and I always pray for him. Of all of the brethren, he stayed home the longest. After every air raid, he went out looking for the branch members. That was very encouraging for us. . . . Brother Andreas Leyer was killed in battle. He did a lot of work in the branch and was a great man. Brother Dönig died with a strong testimony of the truth. We lost track of him three years ago. Among the few items we could rescue are the holy scriptures you gave us. Shortly after Mother died, I worked in the mission office until I was called to a Pflichtjahr for ten months in 1942. My sister [Lina] and I took those books with us. [23]

Fig. 11. The ruins of downtown Mannheim in 1945. (R. Hechtle)

Fig. 11. The ruins of downtown Mannheim in 1945. (R. Hechtle)

Perhaps the last soldier of the West German Mission to return from a POW camp after World War II was Horst Prison, who arrived in Saarbrücken on December 31, 1949. His wife, Elfriede, had been living with his parents for some time and vividly recalled their reunion:

I was at the market with my mother-in-law one day, and I had heard on the radio that [Horst] was on his way home. Everybody else thought I was crazy because I was still waiting for him to come home. The next morning at 2 a.m., I got a telegram telling me that I should pick him up at the Saarbrücken railroad station the next day. See, I was not crazy! But when I saw him, I realized that he was no longer the man I had married. The war had changed him. For a while, it was very difficult [to be with him]. He only said yes and no—nothing else. He did not want to see anybody. After quite a long time, he got back into our routine. I needed a lot of patience.

Elfriede offered this summary of her spiritual status after so many challenging experiences: “My testimony was strengthened through prayer. I found peace because I prayed. I have to say that all these things, although they might have been terrible and difficult to bear, made me a stronger person. There were so many instances in which I felt the help of my Heavenly Father. I knew he protected me—absolutely.” [24]

During the war, the members of the Mannheim Branch had been scattered to the four winds and suffered heavy losses in many respects, but the testimonies of survivors were strong and the future of the branch among the ruins of Hitler’s Third Reich was promising.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Mannheim Branch did not survive World War II:

Susi Maria Bentz b. Mannheim, Baden, 29 Jul 1910; dau. of Theodor Bentz and Eva Pfeiffer; bp. 19 Dec 1926; conf. 19 Dec 1926; m. —— Braun; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 37; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 386)

Johann Billian b. Mannheim, Baden, 25 Jun 1894; son of Johann Billian and Therese Weigert or Weigart; bp. 27 Jun 1908; conf. 25 Jul 1908; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 1; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 345)

Katharina Burkart b. Hagenbach, Pfalz, Bayern, 25 Jan 1872; dau. of Franz Burkart and Katharine Gehrlein; bp. 13 Feb 1927; conf. 13 Feb 1927; m. 18 Jul 1927, —— Mai; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 44; FHL microfilm 245225; IGI)

Elsa Frieda Fink b. Ludwigshafen, Pfalz, Bayern, 2 Nov 1917; dau. of Johann Fink and Frieda Emma Scharpf; bp. 22 Nov 1925; conf. 22 Nov 1925; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 4; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 7; FHL microfilm 25766)

Eugenie Elisa Fink b. Rheinau, Mannheim, Baden, 12 Jun 1912; dau. of Johann Fink and Frieda Emma Scharpf; bp. 24 Sep 1921; conf. 24 Sep 1921; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 3; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 5; FHL microfilm 25766)

Karoline Fresch b. Vellberg, Württemberg, 28 Sep 1879; dau. of Georg Fresch and Margarethe Wolpert; bp. 2 Apr 1920; conf. 4 Apr 1920; m. Otto Bruno Hätscher; missing as of 10 Dec 1944 (FHL microfilm 68797, no. 350; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 350; FHL microfilm 68799, no. 7)

Friedrich Hätscher b. Mannheim, Mannheim, Baden, 14 Feb 1913; son of Otto Bruno Hätscher and Karolina Fresch; bp. 1 Oct 1921; conf. 2 Oct 1921; missing as of 10 Dec 1944 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 9; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 351)

Otto Bruno Hätscher b. Lissa, Posen, Preussen, 20 Mar 1876; son of Otto Hätscher and Ann Schwank; bp. 21 Aug 1920; conf. 22 Aug 1920; missing as of 10 Dec 1944 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 6; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 349)

Ludwig Wilhelm Harrer; b. Mannheim, Mannheim, Baden, 13 Sep 1912; son of Wilhelm Christian Harrer and Elisabeth Eck; m. Mannheim, Mannheim, Baden, 27 Oct 1934, Lina Deininger; Waffen-SS sergeant; k. Kutilicka, near Wassiljewschtschina, Russia, 22 Feb 1942 (Prison; www.volksbund.de, IGI)

Gustav Wilhelm Emil Herzog b. Mannheim, Mannheim, Baden, 23 Jan 1922; son of Jakob Herzog and Maria Eva Schulz; bp. 1 Feb 1931; conf. 1 Feb 1931; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 66; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 456; FHL microfilm 162782, 1930 and 1935 censuses)

Heinrich August Herzog b. Mannheim 6 Dec 1926; son of Jakob Herzog and Maria Eva Schulz; bp. 8 Sep 1935; conf. 8 Sep 1935; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68797, no. 598; FHL microfilm no. 162782, 1930 and 1935 censuses)

Ludwig Daniel Höflich b. Ludwigshafen, Pfalz, Bayern, 4 May or Sep 1909; son of Ludwig Höflich and Philippine Kratz; bp. 24 Sep 1921; conf. 25 Sep 1921; m.; missing 10 Dec 1944 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 11; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 355)

Ludwig Höflich b. Ludwigshafen, Konstanz, Baden, 2 Aug 1881; son of Wilhelm Höflich and Charlotte Hassel; bp. Ludwigshafen, Pfalz, Bayern, 11 Feb 1930; conf. 11 Feb 1930; m. Philippine Kratz; 1 child; k. air raid 1943 (FHL microfilm 68797, no. 402; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 402; IGI)

Wilhelm Martin Rupprecht Höflich b. Mannheim, Mannheim, Baden, 13 Mar 1915; son of Ludwig Höflich and Philippine Kratz; bp. 26 May 1923; k. air raid 10 Dec 1943 or 1944 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 12; FHL microfilm 68797, no. 356; FHL microfilm 162786, 1935 census)

Karl Josef Hoffmann b. Sinsheim, Heidelberg, Baden, 2 Jan 1886; bp. 16 May 1919; conf. 16 May 1919; d. 1943 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 39; IGI)

Andreas Johann Leyer b. Mannheim, Mannheim, Baden, 14 Jul 1920; son of Johann Georg Leyer and Anna Hess; bp. 1 Feb 1931; conf. 1 Feb 1931; ord. deacon 3 Feb 1935; ord. teacher 30 Oct 1938; lance corporal; d. of wounds Akmene, Lithuania, 18 Aug 1944 (G. Leyer; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 460; FHL microfilm 68799, no. 65; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Johann Georg Leyer b. Mannheim, Mannheim, Baden, 3 Jan 1918; son of Johann Georg Leyer and Anna Hess; bp. 1 Feb 1931; conf. 1 Feb 1931; home guard; d. tuberculosis Mannheim (G. Leyer; FHL microfilm 68799, no. 62)

Georg Müller b. Altleiningen, Pfalz, Bayern, 2 Aug 1870; son of Johann Müller and Juliana Alebrand; bp. 8 Aug 1927; conf. 8 Aug 1927; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 47; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 5)

Gertrud Scharf b. Mannheim, Baden, 26 Oct 1914; dau. of Alois Scharf and Martha Wolf; bp. 21 Jun 1931; conf. 21 Jul 1931; m. —— Kohl; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 68; CR 275 8 2441, no. 460)

Wilhelm August Heinrich Scharrer b. Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Baden, 31 Aug 1900; son of August Scharrer and Emilie Wolf; bp. 21 Jun 1916; conf. 21 Jun 1916; ord. priest 22 Jan 1918; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 330; FHL microfilm 245258, 1930 and 1935 censuses)

Johann Martin Scholl b. Fränkisch Crumbach, Hessen, 12 Jan 1862; son of Johann Jakob Scholl and Margaretha Elisabeth Klinger; bp. 18 Feb 1899; conf. 19 Feb 1899; ord. elder 17 Sep 1916; m. Mannheim, Mannheim, Baden, 7 Jul 1888, Elisabeth Ültzhöfer; 4 children; d. cancer or heart ailment Mannheim, Baden, 29 Feb 1940; bur. Mannheim 4 Mar 1940 (Prison; Stern 1940, nos. 5–6, pg. 95; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 361; IGI, AF)

Karl Friedrich Scholl b. Mannheim, Mannheim, Baden, 25 Mar 1895; son of Johann Martin Scholl and Elisabeth Ülzhöfer; bp. 25 Nov 1906; conf. 25 Nov 1906; m. 4 Dec 1921 or 1927, Maria Berta Littic; d. insanity 30 or 31 Jan 1943 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 15; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 362; IGI)

Emil Hermann Schulz b. Frankenthal, Pfalz, Bayern, 1 Jan 1911; son of Emil Friedrich Herm Schulz and Anna Maria Maltry; bp. 4 Dec 1921; conf. 4 Dec 1921; k. in battle 1942 or MIA 10 Dec 1944 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 19; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 367; IGI)

Peter Schulz b. Mannheim, Mannheim, Baden, 24 Dec 1912; son of Emil Friedrich Hermann Schulz and Maria Maltry; bp. 4 Dec 1921; conf. 4 Dec 1921; ord. priest 10 Feb 1935; missing as of 20 Nov 1945 (CR 375 8 2451, no. 683; FHL microfilm no. 245260, 1925 and 1935 censuses)

Wilhelm Peter Schulz b. Frankenthal, Pfalz, Bayern, 7 Jan 1905; son of Emil Friedrich Hermann Schulz and Anna Maria Maltry; bp. 25 Oct 1922; conf. 25 Oct 1922; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 18)

Friedrich Süss b. Ludwigshafen, Pfalz, Bayern, 21 Dec 1876; son of Johann Süss and Anna Maria Sophia Moritz; bp. 7 Aug 1891; conf. 7 Aug 1891; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 13)

Minna Wagner b. Neuenburg, Württemberg, 22 Aug 1880; dau. of Karl Wagner and Karolin Rörk; bp. 13 Feb 1927; conf. 13 Feb 1927; m. —— Hofbauer; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 43)

Franziska Viktoria Weber b. Raschlovke or Raschlovko, Preussen, 15 Dec 1873; dau. of Christian Weber and Olga Goschalandschie; bp. 30 Aug 1925; conf. 30 Aug 1925; m. —— Max Vogelmann; missing as of 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 31; CHL CR 275 8 2441, no. 10)

Else Wessa b. Ludwigshafen, Pfalz, Bayern, 10 Nov 1907; dau. of Georg Wessa and Anna Klara Bissantz; missing 20 Mar 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 48)

Anton Ziegler b. Mannheim, Mannheim, Baden, 19 Mar 1905; son of Markus Ziegler and Anna Müller; bp. 17 Nov 1929; m. 17 Aug 1929; d. as a soldier crossing a river in Russia 1943 or 15 Feb 1945 or MIA Ostpreussen 1 Jan 1945 (Prison; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Notes

[1] West German Mission branch directory 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[2] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CR 4 12.

[3] The map of the city’s interior shows approximately 150 blocks within a huge half circle. The house numbers on each block run consecutively around the block in a clockwise direction. Before the war, there were essentially no street names in that part of the city. The landlord to whom the branch paid rent was Albert Speer, at that time Hitler’s personal architect and a rising star in Nazi Germany. He later became the minister of war production and was sentenced to twenty years in prison at the trial of the major war criminals in Nuremberg in 1945–46. His address on Schloss Wolfsbrunnenweg in Heidelberg in 1939 was the same location where the author interviewed Speer in October 1975.

[4] Horst Peter Prison and Elfriede Deininger Prison, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, October 24, 2008; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[5] Gottfried Leyer, interview by the author, Hyrum, Utah, July 29, 2008.

[6] Walter E. Scoville, papers, CHL MS 18613; translated by the author. Scoville’s ambitious correspondence with German friends was interrupted when the United States entered the war on December 8, 1941.

[7] Paul H. Kelly and Lin H. Johnson, Courage in a Season of War (2002), 264.

[8] Manfred Zapf, telephone interview with the author in German, April 7, 2009.

[9] Kelly and Johnson, Courage in a Season of War, 268–69.

[10] Manfred Hechtle, interview by the author, Hyrum, Utah, July 29, 2008.

[11] Ralph Hechtle, interview by the author, Brigham City, Utah, October 21, 2006.

[12] Kelly and Johnson, Courage in a Season of War, 266.

[13] Ibid., 266–67.

[14] Ibid., 268.

[15] Ibid., 268

[16] He had been living in Kenzingen (south of Karlsruhe) for some time after being evacuated from Mannheim.

[17] Mannheim Branch general minutes, CHL LR 5344 21.

[18] Ludwigshafen city archive.

[19] Kelly and Johnson, Courage in a Season of War, 270–71.

[20] Ibid., 271–72.

[21] Ibid., 272.

[22] Mannheim Branch general minutes.

[23] Walter E. Scoville, papers.

[24] Kelly and Johnson, Courage in a Season of War, 272.