Lübeck Branch

Roger P. Minert, “ Lübeck Branch, Hamburg District,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 155–62.

One of only two Baltic Sea port cities in the West German Mission, Lübeck is located forty miles northeast of Hamburg. Famous for its seven church steeples, the city had a population of 154,811 when World War II approached. The branch in that city numbered 109 persons, including five elders and seven men and boys who held the Aaronic Priesthood. Like so many other branches in the mission, this one had a very large number of adult women but few children.

| Lübeck Branch [1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 5 |

| Priests | 1 |

| Teachers | 4 |

| Deacons | 2 |

| Other Adult Males | 22 |

| Adult Females | 66 |

| Male Children | 5 |

| Female Children | 4 |

| Total | 109 |

Leonard J. Bingham, a missionary from the United States, was the branch president in Lübeck on August 25, 1939, when he was instructed to depart the city with his colleague Joseph Loertscher. In his account of leaving the city on Saturday, August 26, he made no mention of designating a successor to lead the branch. However, all indications are that Elder Bingham’s first counselor, Gottlieb Wiborny, assumed the position of branch president. [2]

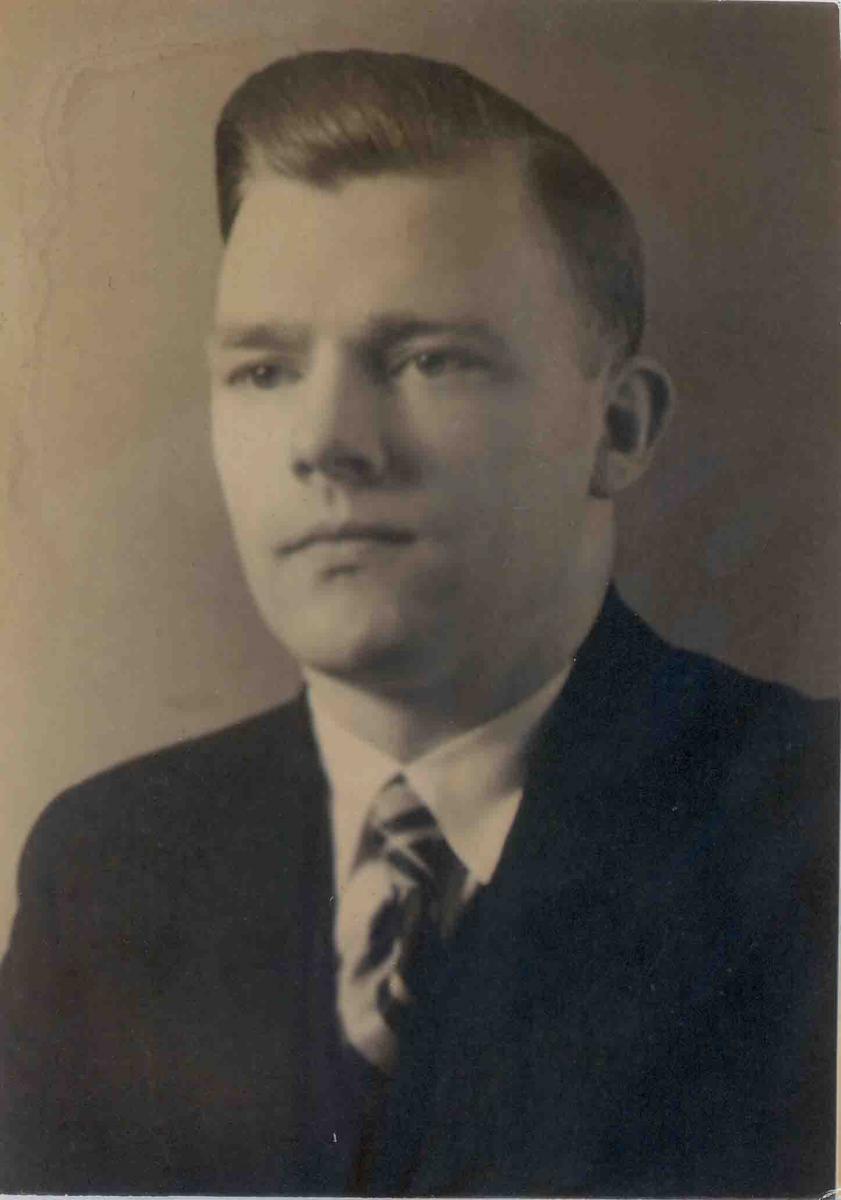

Fig. 1. Friedrich (Friedel) Sass was the second counselor to Hamburg District president Alwin Brey when World War II began. (J. Sass)

Fig. 1. Friedrich (Friedel) Sass was the second counselor to Hamburg District president Alwin Brey when World War II began. (J. Sass)

When World War II began, the branch was meeting in rented rooms at Mühlenstrasse 68 in Lübeck’s downtown. Reinhold Meyer (born 1923) recalled the location as “an old office building. There were three or four rooms upstairs. One was a double room that we used as a chapel, and there were classrooms for the children. There was a sign outside indicating the presence of the Church there. It was an attractive building, and I was not ashamed to go there.” [3] He recalled an attendance of perhaps fifty to sixty persons on a typical Sunday.

Sunday School was held at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting at 7:00 p.m. The MIA meetings were held on Tuesday evenings at 8:00 p.m., the Primary Organization on Wednesdays at 3:00 p.m., and the Relief Society on Thursday evenings at 8:00 p.m. Reinhold remembered that they took the glass sacrament cups home each week and cleaned them. [4] According to Wilfried Süfke (born 1934), there was a pump organ in the main meeting hall, as well as a small stage. He remembered sitting on individual seats (rather than benches) that could be moved to the sides of the rooms to facilitate social activities. [5]

The Meyer family lived at Burgkoppel 33 in Lübeck, and it took them about forty-five minutes to walk to church. Making the trip twice each Sunday meant that the Meyers spent three hours walking. “We never missed meetings,” explained Reinhold, “and it was dark when we got home to have our dinner.” Sister Meyer had been a widow since 1924 and raised seven children on her own. Fortunately, she was able to remain a housewife during those years and was faithful in taking them to the meetings.

Reinhold Meyer was employed in the aircraft industry in the early years of the war, helping to produce the Heinkel 111 and Dornier 217 airplanes. He knew that the planes were to be used to bomb the enemy and that the enemy might bomb Lübeck in return. During the first three years of the war, there were numerous air-raid alarms, but the local residents did not take them seriously. According to Reinhold, “We made our basement nice with beds down there. Instead of changing our clothes and running down there every time the sirens went off, we just slept there.”

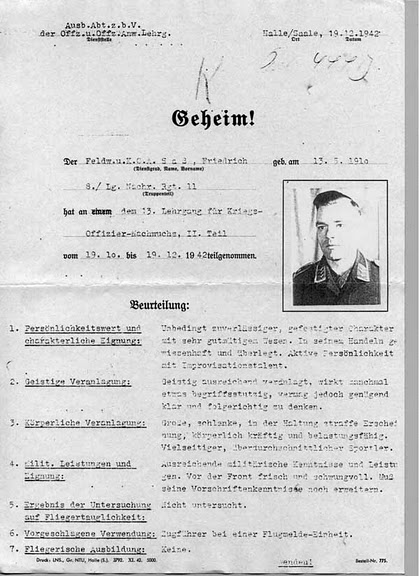

Fig. 2. The officer’s profile for Friedrich Sass was classified as geheim (secret). (J. Sass)

Fig. 2. The officer’s profile for Friedrich Sass was classified as geheim (secret). (J. Sass)

Many residents of the industry-poor city of Lübeck failed to take the air-raid sirens seriously in the early years of the war. Wilfried Süfke recalled the following:

When we heard the alarms, we did not even go into the basement but stayed in our apartment. . . . It was dangerous and careless of us to do that, but back then it seemed reasonable. [Later] we heard of people who were injured or killed, and then we decided to go into the basement quite often. . . . Being only seven years old at the time, I was not afraid of dying.

The beautiful old city of Lübeck was destroyed to a great extent in a single attack on March 29, 1942. The towers of five of the seven prominent churches were gone, and much of the city’s core was reduced to rubble. Fortunately, the Meyers lived far enough from that area to escape harm. The Mühlenstrasse meetinghouse was not destroyed but was soon confiscated by the city government to be used as a place for homeless residents. More than three hundred people lost their lives in the attack. The official report showed that 7 percent of the city’s structures were totally destroyed, 10 percent severely damaged, and 41 percent slightly damaged. [6]

Fig. 4 and 5. The family of Friedrich (Friedel) and Hedwig (Heidi) Sass in about 1942. (J. Sass)

Fig. 4 and 5. The family of Friedrich (Friedel) and Hedwig (Heidi) Sass in about 1942. (J. Sass)

Fig. 3. Members of the Lübeck Branch on an outing in a local forest. (J. Sass)

Jürgen Sass (born 1933) recalled with great clarity the night his hometown was so badly damaged:

The alarm had sounded; we were in the front room dressing when a tremendous explosion rattled doors and windows. As we peeked through the blinds, the sky was lit up by four illuminating devices which had been dropped to serve as target guides for British bomber squadrons. We fled immediately to our shelter, where we were soon joined by our grandmother. . . . Again and again, muffled explosions could be heard through the din of anti-aircraft fire. . . . Suddenly we were startled by a loud whine, followed by an earsplitting explosion which shattered windows and knocked tiles off the roof. A bomb had landed and exploded in a garden plot across the street. That was a close call!! [7]

When Jürgen Sass was eight years old, his mother, Hedwig, took him to the rooms of the St. Georg Branch in Hamburg, where there was a baptismal font (one of only three in the Church in all of Germany). [8] Jürgen’s father, Friedrich (Friedel) Sass, had been stationed there in the air force for several years already and was fortunate to perform his son’s baptism on May 23, 1942. Shortly after that event, Brother Sass was transferred to a combat zone. [9]

Fig. 6. Friedel Sass received the first-place medal for his age-group in the army 10-kilometer run in 1942. He ran the distance in 42:08.5. (J. Sass)

Fig. 6. Friedel Sass received the first-place medal for his age-group in the army 10-kilometer run in 1942. He ran the distance in 42:08.5. (J. Sass)

According to the branch history, “Brother Wiborny guided the branch through the trying and fateful years of the war.” [10] No reports regarding him or his family could be found as of this writing. The branch history offers only one paragraph about the status of the Latter-day Saints in Lübeck during the war:

The members gathered for meetings in the former civil registry office on Mühlenstrasse. Following the bombing of Lübeck in 1942 that destroyed 60% of the city, the meeting rooms were confiscated and the members were again compelled to hold meetings in their homes. At times during the war, meetings were also held in Reinfeld [seven miles east of Lübeck]. [11] A book of meeting minutes was kept from January 3, 1943 to April 21, 1946. Walter Meyer usually conducted the meetings, but the names Hans Kufahl and Reinhold Meyer occur in this capacity as well. The average attendance was 10–17 persons, most of whom were members of the extended Meyer family. [12]

According to Reinhold Meyer, the first meetings after the disastrous attack of 1942 were held in a Catholic church (“but only once”), then in the apartment of his elder brother, Walter Meyer. Wilfried Süfke recalled sitting on the floor under such circumstances, but there was enough room. “We didn’t have accompaniment on the pump organ any more, but we could still sing the hymns.”

Late in 1942, Reinhold was drafted into the Luftwaffe and was stationed first in Reims, France. Initially, he was classified among the “flight personnel,” but by then the number of German airplanes had decreased to the point that he was reassigned. “I never did have to fly, and I’m glad for that. [The Allies] had so many planes. I counted them later on—a thousand planes and I couldn’t see any more.” Following a short and intense illness, he was assigned to office duty. In 1943, he was transferred to Belgium and trained to drive motorcycles, automobiles, and trucks. Once while he was home on leave, his comrades were all sent to the Soviet Union—a move that cost many of them their lives. Friedrich was spared, at least for a while.

Friedel Sass was transferred to the Eastern Front in 1943 for a very short time, but long enough to have a painfully personal experience. He confided the story to his mother, who often related it to his sons:

It may have been while he was delivering a message, when he suddenly found himself face-to-face with a Russian soldier. It was a matter of who was going to pull the trigger first, and it was [your] father that did. He said it’s something to see somebody a block or so away shooting at you and you shoot back, that’s one thing, but to be face-to-face with a living being, that is something else. He must have stayed with that man for a bit [before he died], because he learned that he had three children, just as [your] father did. He left a wife, just as [your] father did. He said it was a very, very traumatic experience. [13]

Specific memories of life in Lübeck during the war remain clear in Jürgen Sass’s mind, such as this one:

I was probably at the most, ten years old, while on the way to my elementary school . . . and there was a field where some construction was going on. [The workers were] forced laborers—probably Poles or Russians—and there was a guard with a gun. Whoever they were, there was a fistfight. . . . [They were] really fighting hard over a strangled cabbage on which all the leaves were already gone. That affected me. . . . I figured, gee, those guys must be starving. [14]

Jürgen Sass saw his father only on rare occasions during the war. Friedel Sass had been drafted in 1939, so his children grew up essentially without him. Jürgen recalled two poignant letters written by his father to Friedel’s mother (Jürgen’s grandmother). Brother Sass wrote one such letter on his wedding anniversary (September 30) and told of an American artillery barrage that could have killed him. “Please, Lord, if I have to die, not today!” he had thought during the barrage. [15]

Jürgen avoided the Hitler Youth experience for the first year, then volunteered after all: “I felt the need to belong to an organization of other young boys.” One occasion must have been quite exciting, namely when the boys were camping and engaging in war games: “American planes flew overhead, and surrounding anti-aircraft batteries began to fire. Our group leader, who was probably not much older than 14, had us stand under trees, while [shrapnel] fragments rained around us. . . . Fortunately, none of us got hit.” [16]

Wilfried Süfke was fortunate to have both parents home during the entire war. His father, Walter, was a salesman of agricultural seeds. His mother, Minna, owned and operated a small grocery store on the main floor of the apartment building in which the family lived. According to Wilfried, “Even when the British came in [as conquerors], we were able to keep the store running.” Another major advantage in the life of young Wilfried was that he was never sent away from Lübeck as part of the children’s evacuation program (Kinderlandverschickung), unlike hundreds of thousands of children all over Germany.

Friedel Sass was a very talented man. A dedicated member of the Church, he was serving as second counselor to Alwin Brey, the president of the Hamburg District, when the war began. From the beginning of his army service, he was selected as an officer candidate and moved steadily up the ranks. The excellent collection of documents preserved by his family attest to the stellar reputation he enjoyed among both superiors and subordinates. He appeared to be a faithful soldier who enjoyed serving his country. The many photos taken of him under both military and civilian circumstances show a man who seemed very happy with his life.

Holger Sass (born 1938) was a child when Allied airplanes coursed over Lübeck in the last years of the war. To him, it was all quite exciting, and he was totally unaware of the danger. “One time, when the sirens sounded to let us know that everything was okay, we could [go outside and] look at the fires. If you’re a kid at that young age, it’s kind of special.”

During the summer of 1944, Reinhold Meyer was involved in a most precarious undertaking. A German -1 unmanned rocket had plummeted into the French countryside and needed to be disarmed. Reinhold drove an expert he called “Old Gus” to the site and was required to hand him tools during the delicate operation. Just a few seconds after Old Gus removed the firing pin, it popped. “If the device had triggered just a few seconds earlier, I wouldn’t be here telling this story,” he claimed. However, the device injured Old Gus’s hand, and Reinhard helped stop the bleeding. Then the two attached a few pounds of dynamite, retreated to a safe distance, and set off the charge to totally destroy the rocket’s lethal payload.

When the Allied landings took place on the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944, Reinhold’s unit was about a hundred miles inland. They were assigned to construct barriers to hinder the Allied advance, but there were simply no supplies with which to do so. “We just kept moving back, away from them,” he recalled. When the Allies entered Paris in August, Reinhold was actually staying in a hotel there and came very close to being captured. His unit quickly moved northeast toward Germany’s Eifel forest.

By early 1945, Reinhold Meyer had crossed the Rhine River into the heart of Germany and had moved steadily north and east ahead of the advancing British army. In April 1945, he and his comrades buried their weapons and surrendered to the British. They were moved to Lüneburg and then to Hitzaker on the Elbe River. For several nights, they had no shelter and simply slept in the sand. Once, Reinhold was ordered to latrine duty, which he of course did not like. Because nobody was really paying attention to him, he simply walked away from the distasteful task.

Just days before he was killed in Remiremont, France, Friedel Sass wrote a letter to his mother including the following lines:

For the second time I have lost all my belongings. . . . Mostly I regret the loss of my briefcase with the addresses of my comrades from the Eastern Front, as well as my camera. Yesterday I bought for Jürgen’s birthday a wristwatch, Swiss brand, with fifteen jewels. Now I have to see how I can get it home in time for his birthday. Unfortunately, I have not been able to get anything for my other two boys. [17]

Jürgen likely never received that watch because his father was killed a few days later, on October 12, 1944. The family received the sad news one day before Jürgen’s eleventh birthday.

Figs. 7 and 8. Friedel Sass was killed in France on October 12, 1944. He lies buried in a German military cemetery. (J. Sass)

Figs. 7 and 8. Friedel Sass was killed in France on October 12, 1944. He lies buried in a German military cemetery. (J. Sass)

During the last days of the war, Holger Sass witnessed what to him was a most confusing incident. Standing near an army warehouse, he noticed that there were small fires inside even before a German officer ordered several of his men to go inside. “We never knew what was in there, but I think they were trying to destroy the stuff so that the [enemy] would not get it,” he surmised. “They started a fire in the building, and then some soldiers went back in. They must have known that they would not get out because it was already burning. I think that seeing that [event] would affect anybody.”

The British army entered the city of Lübeck on May 2, 1945, six days before the war officially ended. [18] No attempt was made to defend the city. According to young Jürgen Sass, “The subsequent occupation by British troops proved to be rather tolerable. There seemed to be little animosity on either side. . . . Church services . . . were restored, at first in a member’s home, later on in schools.”

The branch history offers a single sentence regarding the Latter-day Saints in Lübeck in the months following the end of the war: “Many refugees from Selbongen, Königsberg, Stettin and Pomerania (in the East German Mission) made their way to Lübeck and the towns nearby, bringing perhaps as many as 400 members to Lübeck.” [19]

As a German soldier, Reinhold Meyer was a priest in the Aaronic Priesthood. While away from home, he could never attend a Church meeting and had no scriptures to read. Only once did he come into contact with another German LDS soldier—a young man from Hamburg’s St. Georg Branch—but the experience was not a positive one. “He acted like he didn’t know me, but I had stayed in his home once during a district conference in Hamburg. I don’t know why he didn’t want anything to do with me.”

In August 1945, Reinhard was put on a truck and driven to Lübeck. His family had never been told his whereabouts. “My mother had been praying for me. Several times bombs had fallen close to me and could have killed me, but I was protected. And I never fired my gun at the enemy. I never killed anybody.”

In Memoriam

The following members of the Lübeck Branch did not survive World War II:

Herbert Emil Derr b. Chemnitz, Sachsen, 22 Nov 1909; son of Emil Derr and Hulda Spindler; bp. 11 May 1918; conf. 11 May 1918; ord. deacon 17 Sep 1928; ord. teacher 16 Jan 1932; naval officer; k. Clisson, Nantes, 13 Aug 1944; bur. Pornichet, France (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 13; www.volksbund.de; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 813)

Henriette Maria Helene Dürrkop b. Lübeck 6 Sep 1870; dau. of Jürgen J. H. Dürrkop and Dorothea Horstman; bp. 28 Sep 1923; conf. 28 Sep 1923; m. 11 Nov 1894, Johann Heinrich Friedrich Klinkrad; d. 30 Jul 1944 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 35)

Heinrich Gottfried Christoff Kock b. Mölln, Lauenburg, Schleswig-Holstein, 24 Apr 1874; son of Heinrich Adolf Kock and Dorothea K. Wilhelmine Dau; bp. 27 Feb 1912; conf. 27 Feb 1912; m. Lütau, Lauenburg, Schleswig-Holstein, 23 Apr 1899, Johanna Marie Sophie Berlin; 10 children; d. heart ailment Lübeck 13 Apr 1944 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 27; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 970; FHC microfilm 271380, 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Heinz Hugo Helmuth Kock b. Lübeck 29 Dec 1923; son of Heinrich Gottfried Christoff Kock and Johanna Marie Sophie Berlin; bp. 11 May 1934; conf. 4 Jun 1931; d. pneumonia POW camp Russia 17 Nov 1945 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 116; FHC microfilm 271380, 1930 and 1935 censuses)

Helmut Ludwig Friedrich Heinrich Kock b. Lübeck 18 Feb 1916; son of Heinrich Gottfried Christoff Kock and Johanna Marie Sophie Berlin; bp. 27 Sep 1924; conf. 28 Sep 1924; rifleman; k. in battle Zambrow, Poland, 11 Sep 1939; bur. Mławka, Poland (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 30; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 44; www.volksbund.de; FHC microfilm 271380, 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Marianne Josepha Sophie Lenz b. Lübeck 3 Jan 1908; dau. of Thomas Lenz and Martha Frieda Georgine Krüger; bp. 17 Jun 1929; conf. 17 Jun 1929; m. 2 Mar or May 1936, Walter Spiegel; d. heart failure 23 Nov 1942 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 42; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 817)

Anna Maria Elisabeth Lübcke b. Lehmrade, Lauenburg, Schleswig-Holstein, 31 Aug 1868; dau. of Johann H. Joachim Lübcke and Margaretha M. M. Hardekaper; bp. 1 Jun 1900; conf. 1 Jun 1900; m. 8 Jan 1892, Johann J. H. Burmeister; d. 28 Aug 1943 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 11; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 553; FHL microfilm 25733, 1930 and 1935 LDS censuses)

Dorothea Maria Elisa Agnes Franziska Mecker b. Lübeck 30 Mar 1863; dau. of Johann Joachim Heinrich Mecker and Johanna Regina Henriette Rosenhagen; bp. 8 Jul 1920; conf. 11 Jul 1920; m. Lübeck 5 Oct 1883, Johann Heinrich Friedrich Naevecke; eight children; d. cardiac asthma, angina, and old age 31 Dec 1944 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 61; IGI)

Edwin Ewald Meyer b. Lübeck 26 Sep 1941; son of Ewald Johann Wilhelm Meyer and Martha H. O. Luth; d. heart attack 27 Nov 1941 or 1944 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 151; IGI)

Gudrun Adelgund Genovefa Meyer b. Lübeck 9 Dec 1939; dau. of Walter Hans Bernhard Meyer and Cäcilie Sophie Frieda Kost; d. pneumonia Lübeck 5 May 1944 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 148; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 422)

Hermann Johann Karl Meyer b. Eggerstorf, Grevesmühlen, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, 16 Mar 1876; son of Anna S. D. Meyer; bp. 12 Jul 1924; conf. 12 Jul 1924; ord. deacon 3 Sep 1925; ord. teacher 4 Nov 1934; ord. priest 17 May 1936; m. Grevesmühlen, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, 13 Oct 1899, Anna Marie Caroline Johanna Mathilde Tack; three children; 2m. 1 Nov 1919, Friede D. D. Busekist-Best; d. heart attack Lübeck 27 Apr 1941 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 59; IGI)

Walter Hermann Julius Meyer b. Lübeck 16 Jan 1919; son of Hermann Johann Karl Meyer and Frieda Dorisa Dorothea Best; bp. 3 Jul 1931; conf. 3 Jul 1931; k. in battle Italy 3 Nov 1944 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 102; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 74–75; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 59; IGI)

Frieda Maria Berta Ollrogge b. Lübeck 12 Sep 1899; dau. of Heinrich Ollrogge and Dora Rickmann; bp. 3 Jul 1931; conf. 3 Jul 1931; m. 17 Mar 1922, Carl Friedrich Emil Schiemann; d. cramps 6 Sep 1939 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 105; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 14)

Anna Luise L. Plückhalm b. Dambeck, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, 17 May 1914; dau. of Gustav Plückhalm and Martha Bähls; bp. 9 Apr 1928; conf. 9 Apr 1928; missing as of 1 Feb 1946 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 150; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 436)

Heinrich Christian Ernst Rönpage b. Moisling, Lübeck, 28 Aug 1864; son of Hans Heinrich Ernst Rönpage and Sophie M. Maass; bp. 20 May 1910; conf. 20 May 1910; m. Lübeck 25 Jul 1891, Johanna Marie Sophia Faasch; eleven children; d. old age 19 Sep 1940 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 66; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 636; IGI)

Margarethe Helene Wilhelmine Rönpage b. Lübeck 14 Jan 1893; dau. of Heinrich Christian Ernst Rönpage and Johanna Maria Sophia Faasch; bp. 30 Jun 1910; conf. 30 Jun 1910; m. 10 Jun 1915, Ludwig A. J. Wegner; d. 4 Oct 1945 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 88; IGI)

Friedrich Adolf August Sass b. Lübeck 13 May 1910; son of August Wilhelm Hermann Sass and Frieda Sophie Dorothea Stephan; bp. 3 Jul 1931; conf. 3 Jul 1931; ord. deacon 11 Jan 1932; ord. teacher 7 May 1933; ord. priest 21 Jun 1933; ord. elder 16 Apr 1935; m. Lübeck 23 Sep 1932, Hedwig Wilma Minna Johanna Ront; three children; lieutenant; k. in battle Remiremont, Vosges, France, 12 Oct 1944; bur. Andilly, France (J. Sass; www.volksbund.de; CHL CR 275 8, no. 2443, no. 103; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 17; photo, IGI)

Carl Friedrich Emil Schiemann b. Grevesmühlen, Mecklenburg-Schwerin, 30 Aug 1890; son of August Schiemann and Dora Burmeister; bp. 3 Jul 1931; conf. 3 Jul 1931; m. 17 Mar 1922, Frieda Maria Berta Ollrogge; d. stomach surgery 19 Dec 1944 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 104; CHL CR 275 8 2458, 496; CHL CR 275 8 2438, no. 13)

Emil Friederich Vollrath Steinfeldt b. Lübeck 11 Sep 1908; son of Johannes Heinrich Joachim Steinfeldt and Hedwig Wilhelmine Charlotte Bohnsack; bp. 24 Sep 1921; conf. 24 Sep 1921; m. Grete Hansen (div.); k. in battle Russia 27 Oct 1942 (FHL microfilm 68799, no. 77; CHL CR 275 8, no. 519)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[2] Leonard J. Bingham, autobiography, 125, CHL MS 18074. See also West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[3] Reinhold Meyer, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, November 3, 2006.

[4] West German Mission branch directory, 1939.

[5] Wilfried Süfke, telephone interview with the author in German, February 16, 2009; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[6] Lübeck city archive.

[7] Jürgen Sass, autobiography (unpublished, about 1985).

[8] The other baptismal font was in the rooms of the Essen Branch of the Ruhr District, also in the West German Mission.

[9] Sass, autobiography.

[10] Fred Warncke et al., Geschichte der Gemeinde Luebeck, 1880–1997 (typescript, 1997), 2, CHL LR 5093 21.

[11] There is no explanation for meetings being held at this location. None of the branch leaders listed in 1939 lived in Reinfeld.

[12] Lübeck Branch history, 3.

[13] The family believes that Brother Sass was awarded the Iron Cross for successfully delivering the message under hazardous conditions.

[14] Jürgen Sass, interview by the author, May 25, 2006, Ogden, Utah.

[15] Sass, interview.

[16] Sass, autobiography.

[17] As cited in Sass, autobiography.

[18] Lübeck city archive.

[19] Lübeck Branch history, 5.