Kiel Branch

Roger P.Minert, “Kiel Branch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 384–393.

The port city of Kiel is located on a fjord of the Baltic Sea near the eastern end of the canal that joins the Baltic to the North Sea. The capital of the province of Schleswig-Holstein for many years, the city had 261,298 inhabitants when World War II began. As a crucial venue for maritime operations, the city’s workforce was primarily occupied in the construction and maintenance of ships of war.

The branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Kiel was relatively strong with 175 members, among whom thirty-six were priesthood holders. Since May 4, 1936, the branch meetings had been held in rented rooms in the old Hotel Kronprinz at Hafenstrasse 13–15. [1] The branch president at the time was Kurt Müller, and it was his honor to greet Elder Joseph Fielding Smith in Kiel for a conference on August 22, 1939. Elder Smith and his wife, Jessie Evans Smith, were traveling with mission president M. Douglas and Evelyn Wood through northern Germany. Saints from other branches in the district were among the 108 persons who attended the event. Little did anyone know that the visitors and American missionaries in Germany would be instructed to leave the country just three days later. [2]

| Kiel Branch [3] | 1939 |

| Elders | 13 |

| Priests | 6 |

| Teachers | 3 |

| Deacons | 14 |

| Other Adult Males | 28 |

| Adult Females | 101 |

| Male Children | 6 |

| Female Children | 4 |

| Total | 175 |

The branch directory for the late summer of 1939 shows leaders in all organizations except for the Primary. Wilhelm Metelmann and Heinz Kuhr were the counselors to Kurt Müller; Felix Schmidt, the superintendent of the Sunday School; and Gustav Girnus, the leader of the YMMIA. Eva Behrendt led the YWMIA, and Fanny Metelmann was the president of the Relief Society. Brother Metelmann was also the genealogy expert, and Der Stern magazine was promoted by Johann Ceglowski. [4]

Fig. 1. Else Mueller and her infant sonLotharin 1940. (L. Mueller)

Fig. 1. Else Mueller and her infant sonLotharin 1940. (L. Mueller)

Ursula Leschke (born 1930) was baptized by the American missionaries on the beach by the Kiel harbor just before the war began. Her father was not a member of the Church, but her mother was dedicated to the gospel and took Ursula along as she made visits to sisters of the Relief Society. The family lived in the suburbs east of the harbor. Ursula recalled making the long walk to the harbor, then taking a ferry across to the city center, then walking about fifteen minutes to the Hafenstrasse address. [5]

The location of the branch rooms was nice (very close to the city center), but Ursula recalled some negative aspects of the facility: “It was an old beer hall and we had to clean it up every week before we could use it. I believe that it was just one large room with a small podium.”

The war that began in September 1939 was not the only challenge Brother Müller had to deal with in those days. According to the branch history, high water from the Kiel Fjord reached the old Hotel Kronprinz on October 29, and church meetings were canceled. [6] The same problem occurred on January 21, 1940, and on November 2, 1941.

Changes happened quickly in the LDS Church in the first months of the war, principally because many of the brethren were drafted into the army and had to be replaced in their callings. So it was that Kurt Müller was called to be the president of the Schleswig-Holstein District on December 10, 1939. His successor as branch president was Wilhelm Metelmann.

Fig. 2. The Kiel Branch met in rooms in the old Hotel Kronprinz at Hafenstrasse 13–15. This photograph was used for a postcard in the 1920s. (K. Goldmund)

Fig. 2. The Kiel Branch met in rooms in the old Hotel Kronprinz at Hafenstrasse 13–15. This photograph was used for a postcard in the 1920s. (K. Goldmund)

Karla Radack (born 1930) was sent away from Kiel three times as part of the Kinderlandverschickung program, each time for about nine months. “I was first in Göhren on the island of Rügen, where we used to go to the beach and pick sea grass. The second time, I went to [the state of] Thuringia. The third time was in Frankenstein in Saxony. Our teacher and our [League of German Girls] leader always came along. I was able to go home between all those trips, but I had no contact with the Church when I was away from home.” [7]

Fig. 3. The Radack home on Langenbergstrasse in Kiel. (K. Radack Siebach)

Fig. 3. The Radack home on Langenbergstrasse in Kiel. (K. Radack Siebach)

On one of those trips, Karla saw something she could hardly have comprehended at her age. “In Thuringia we were transported by train. Another train passed us on the other side, and it was full of Jewish people being transported to concentration camps. A lot of German people had water in their hands, and they walked up and gave it to them. That was one of my first recollections of those happenings.” She had no way of knowing the fate of those Jews under a government determined to rid the country of the race.

At the age of sixteen, Ehrenfried Radack (born 1926) was already an active participant in the war. He was drafted along with his schoolmates to operate an antiaircraft battery at the outskirts of Kiel. He was frightened to shoot at airplanes cruising overhead on their way to attack Kiel. As he recalled, “We had seen them destroy our city piece by piece. . . . We had our classes right there [at] the battery, and we continued our education while we were serving our country.” [8]

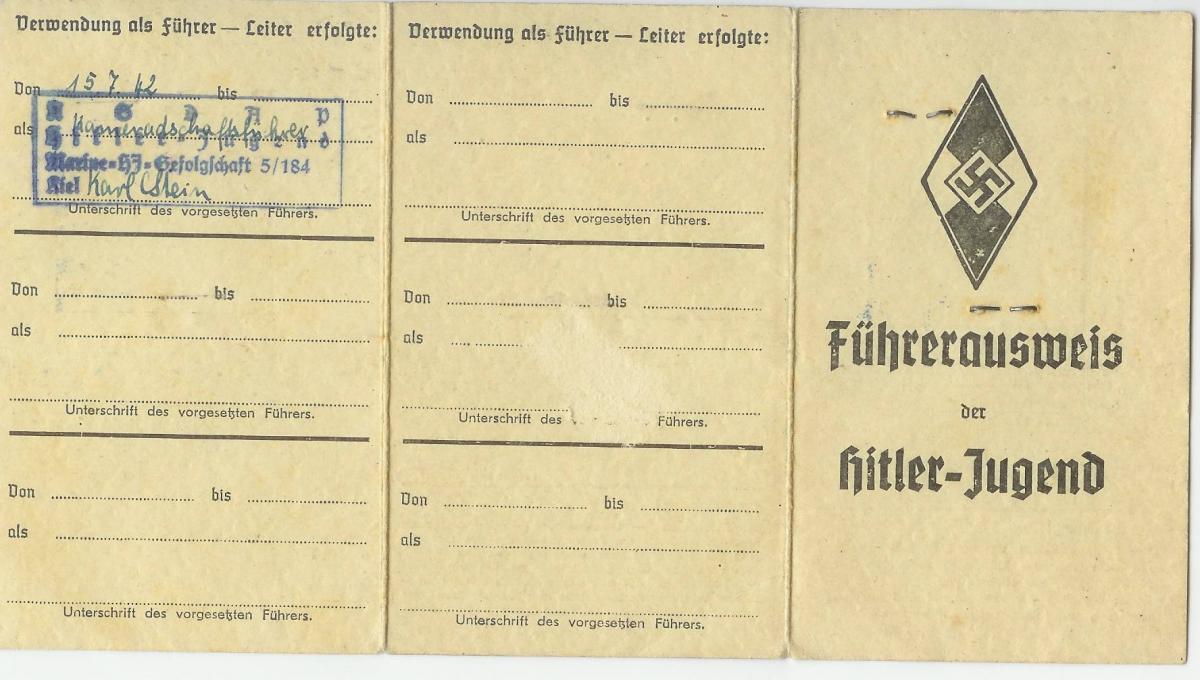

Fig. 4 and 5. Like almost all children in Hitler’s Germany, Ehrenfried Radack was inducted into the Jungvolk at age ten. (R. Radack)

Fig. 4 and 5. Like almost all children in Hitler’s Germany, Ehrenfried Radack was inducted into the Jungvolk at age ten. (R. Radack)

One of the favorite activities of German LDS branches was the baptismal ceremony that happened perhaps once or twice a year. The Kiel Branch history lists only three such occasions during the war years. On two of those occasions, a leader of the West German Mission (Christian Heck or Anton Huck) presided and participated. Baptisms in the Kiel Branch took place on a beach or in a bathhouse.

Ursula Leschke’s father worked as a naval engineer designing submarines. At one point in the war, his office was moved to a place near Hanover, away from the threat of air raids. At home, Ursula’s mother, Ellie, failed to fly the swastika flag from her window at the expected times. One day, she found a note pushed through the mail slot by her door—likely by a patriotic neighbor—reminding her of her duty. Ursula recalled also that her mother did not greet people with the customary “Heil Hitler!” and one day was challenged by a loyal schoolteacher to explain her actions. According to Ursula, her mother offered a brave reply:

My mother said, “I don’t believe in it. I don’t think he is a righteous man or that he’s doing the right things.” Afterwards my mother went home, and she was just scared to death because Fräulein Müller, my teacher, could have easily denounced her to the authorities and my mother would have ended up in a concentration camp. She told me that she went home and she really prayed that Heavenly Father might protect her that she might not be turned in.

All over Germany, LDS men were answering the call to arms, but at least one member of the Church declined to do so. Karla Radack recalled the situation with her uncle:

My uncle Helmut Radack was picked up because he did not want to join the army. One early morning, soon after he had decided against it, he was picked up and put in a concentration camp. He passed away in that camp. They sent the ashes to my grandmother, but my parents later found out that those weren’t his ashes after all. They were probably just scooped up and sent to them in an urn. It was very sad for them.

Fig. 6. Members of the Kiel Branch in 1944 on an outing in a local forest. (M.RadackKramer)

Fig. 6. Members of the Kiel Branch in 1944 on an outing in a local forest. (M.RadackKramer)

It is interesting to note that while building materials were scarce all over Germany during the war, the branch was able to secure what they needed to renovate the rooms at Hafenstrasse 13–15. Perhaps the challenge of finding the needed materials contributed to the long term of renovation that lasted from October 18, 1942, to March 7, 1943. No details regarding the work done are available.

Sometime during the intermediate war years, Ursula Leschke was sent to Bansin on the Baltic Sea island of Usedom as part of the Kinderlandverschickung program. Later, her group was transferred to the city of Bromberg in occupied Poland. In the late summer of 1944, that area was in the path of the invading Red Army, so Ursula and her classmates were sent home to Kiel. Back at home, she learned that her school had been destroyed, so she was required to live in Neumünster (twenty miles to the south), where a school was available. However, Allied airplanes soon attacked that city, and the school there was destroyed too. She returned to Kiel to stay and to experience the end of the war. “By then, the harbor ferry was destroyed and we had to walk all the way around [the south end of] the harbor to attend church meetings.”

Even in Kiel, one of the prime targets for Allied bombers, it was possible for children to have some fun during the war. Karla Radack had this recollection:

To have fun as kids and teenagers, we went out and looked for shells from bombs. I had a little cigar box that I got from a store. My friends and I liked to collect the outside copper shell cases of antiaircraft ammunition. Those were the best pieces, which we would trade. But we also found toys that blew up when you touched them. [9] We used to go to roller-skate, play ball and games. We also went to the beach quite often.

A traditional thrill for German children (and often their parents as well) was a visit by Adolf Hitler. Karla recalled how they heard that the Führer was supposed to come to the harbor in Kiel one day: “My father and I went down there. He bought a little folding chair because the vendor was yelling, ‘Wer den Führer heut’ will sehen, muss auf einem Klappstuhl stehen’ [If you want to see our leader, you’ll need a folding chair.] I sat on his shoulders and was able to see the Führer.”

Fig. 7. Karla Radack Siebach in a dress made out of her father’s old army coat. (K. Radack Siebach)

Fig. 7. Karla Radack Siebach in a dress made out of her father’s old army coat. (K. Radack Siebach)

After finishing public school, Karla was called upon to serve her Pflichtjahr (duty year). She and a friend were assigned to a family with little children in a town not far from Kiel. Unfortunately, the host family did not treat Karla and her friend very well at all. On one occasion, the girls simply went home to Kiel, but the leaders of the Pflichtjahr program forced them to return. Finally, Karla’s mother went to pick up the girls and rescue them from the ill treatment.

In January 1944, Ehrenfried Radack was drafted and classified as an officer candidate. Following five months of training in Oldenburg, he was sent to Saarlautern, near the French border. While there, he learned of the assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler on July 20. His company commander assembled the men, informed them of the abortive attempt, and instructed them that from that time forward they were to use the Hitler salute (the straight, raised right arm) rather than the traditional military salute. As Ehrenfried recalled, “Our commander did not seem to be happy about [the new salute].” [10]

In Saarlautern, Ehrenfried somehow contracted diphtheria and was hospitalized for six weeks. When he asked to return to his unit, the physician ordered him to remain for several more weeks. By the time he returned to the Western Front, the Allies were making steady advances through France and Belgium toward Germany. Soon, Ehrenfried developed an infection in his foot and was again hospitalized, despite the assertion of his sergeant that he was only trying to avoid combat duty. He later realized that his medical problems were blessings in disguise: “How lucky I was; while I was in the hospital, our unit had to fight around Aachen with heavy losses. As I was told later, only one of our group survived.” When he was subsequently transferred from town to town within Germany, he realized that “everything went like it was foreseen [predestined] for me.” He never saw combat on the Western Front but should have on at least two occasions. [11]

Fig. 8. Members of the Kiel Branch in 1944. (M. Radack Kramer)

Fig. 8. Members of the Kiel Branch in 1944. (M. Radack Kramer)

The city of Kiel and its harbor were bombed many times during the war, but the air raid of July 24, 1944, was especially tragic for the Latter-day Saints. The old Hotel Kronprinz was destroyed, and somewhere in Kiel, Wilhelm Metelmann was killed. One week later, a sad branch welcomed Edwin Küchler as their new leader. Gustav Girnus and Walter Köcher continued to serve as the counselors.

“Brother Metelmann had done a lot of genealogy,” recalled Ursula Leschke. She recalled hearing that the branch president was not killed in an air-raid shelter but had died during the firestorm that followed the bombing.

With the destruction of the branch rooms and the apparent lack of suitable rooms elsewhere in the city, the branch began to hold meetings in the homes of members. The history lists the names of six families who hosted Sunday services from October 1944 to March 1945: Girnus, Starkjohann, Leschke, Metelmann, Heimann, and Radack. It is likely that the attendance by that time had been substantially reduced by calls to military service and the departure of mothers with small children to safer places. The remaining Saints could indeed be accommodated in the largest room of a typical apartment.

Karla Radack was in Kiel for the last year of the war and thus experienced many of the worst air raids against that port city. The shelters constructed for the residents were enormous and solid, but she recalled the lack of sufficient ventilation and the air that was almost too thin to support life. People were sitting almost on top of each other, and anxiety was always high, she explained.

Toward the end of the war, we went to bed with our clothes on and with a suitcase ready. I remember one time, when the sirens went off my father came to help me get dressed. But I didn’t want to wake up and was still half-asleep. I remember that was the only time that he hit me. The people were running in the streets and everything was so crowded. Parents had their babies in little baskets and carried them on each side. A voice from the loudspeaker told us to hurry up because the Allied planes were nearly over Kiel.

Young Marlies Radack (born 1940) could recall little more than air raids during her first five years of life: “That was a nightly thing. We slept in our clothes. There was nothing we could do about it, and it happened every night. You take it day by day. And if you don’t know anything different, it’s pretty normal.” [12] Marlies explained that she and her mother usually sat in the basement of their apartment building during the attacks unless there was time to run to the closest public bunker. “One night, a bomb hit really close to the house. And then there was one that was by our door and it didn’t explode. They had to call somebody to defuse it. The glass in our windows was all broken. If that bomb had gone off, we wouldn’t have [survived].”

In early December 1944, Corporal Ehrenfried Radack left Germany on a train headed for Wiener Neustadt, a city south of Vienna, Austria. He was to complete officer candidate training there. In March he and his comrades were informed that if they completed the final examination, they would be promoted to second lieutenant on April 20, Hitler’s birthday. Ehrenfried was indeed one of those who passed the test, but before he could enjoy his new status, it was learned that the Soviet army had broken through the German lines near the border of Austria and Hungary, just a few miles to the east. There followed a most confusing confrontation with the invaders, and Ehrenfried and his friends were sent with small arms to fight against the feared Soviet T-34 tank.

Fig. 9. Ehrenfried Radack in the uniform of an officer candidate. (R. Radack)

Fig. 9. Ehrenfried Radack in the uniform of an officer candidate. (R. Radack)

In the battle that ensued, Ehrenfried watched as his friends were killed, and he was the only survivor. Captured, he was nearly executed several times within one hour. Fortunately, a Soviet officer recognized his rank and singled him out for better treatment. On their way away from the fighting, an odd incident occurred. Ehrenfried wrote this account:

[The Soviet officer and I] approached a trench dug across the road. At this time, when we got ready to jump over, something made me push the Russian officer into the trench with me following him, when [an artillery round] fired by the German artillery hit and exploded at the very spot where we had been standing. He looked at me realizing what had happened, and while we were still in the trench, he shared with me his ration of food. When we finally got up to proceed a few minutes later, he turned me over to a Russian soldier giving him strict orders to take me safely to the battalion commander. He then went away as suddenly as he had appeared to save my life. [13]

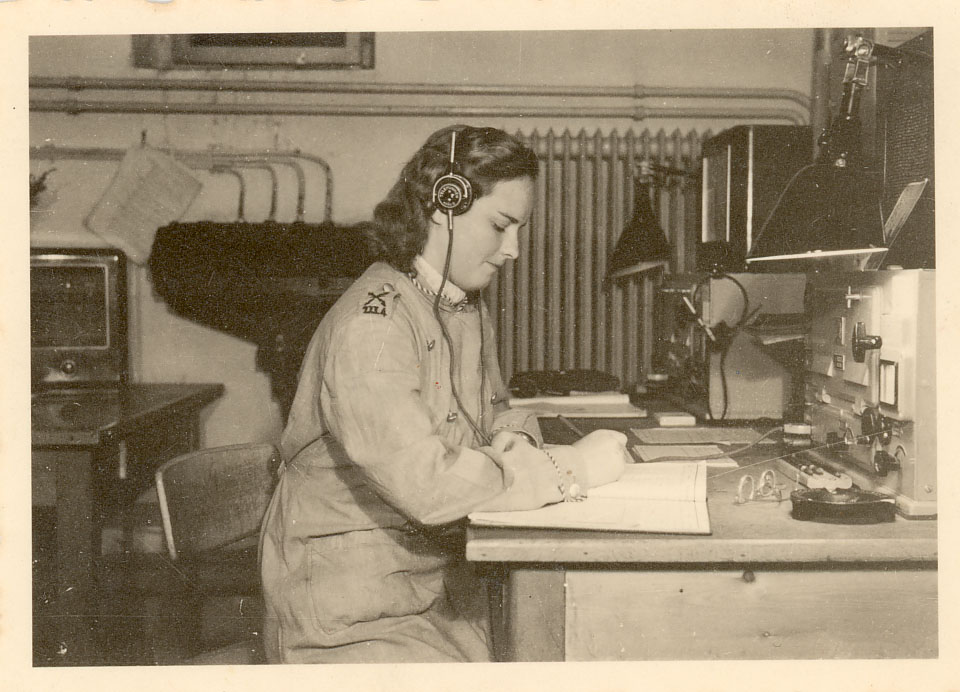

Fig. 10. Edeltraud Radack sending Morse code messages in Husum. (K. Radack Siebach)

Fig. 10. Edeltraud Radack sending Morse code messages in Husum. (K. Radack Siebach)

Lieutenant Radack had survived his first and only combat experience, but he would later describe the adventure that began that day as “the beginning of a long tragedy.” With a thousand other German POWs, he was marched through Austria, Hungary, and other countries on their way to the Black Sea. By the early summer of 1945, he was in the city of Krapotkin, Russia, where his first job was to help rebuild a sunflower factory. [14]

Karla Radack’s last wartime assignment required her to work in a submarine construction facility where she was given drafting projects for four months. That work ended when the facility was bombed out of commission in early 1945.

The branch history does not list any meeting dates between March 11, 1945, and August 19, 1945. It is possible that the events of the last months of the war and the first months of the British military occupation did not facilitate gatherings. On September 12, 1945, Gustav Girnus was installed as the branch president. It would be largely his charge to rebuild the Kiel Branch from the ruins of that large but devastated port city.

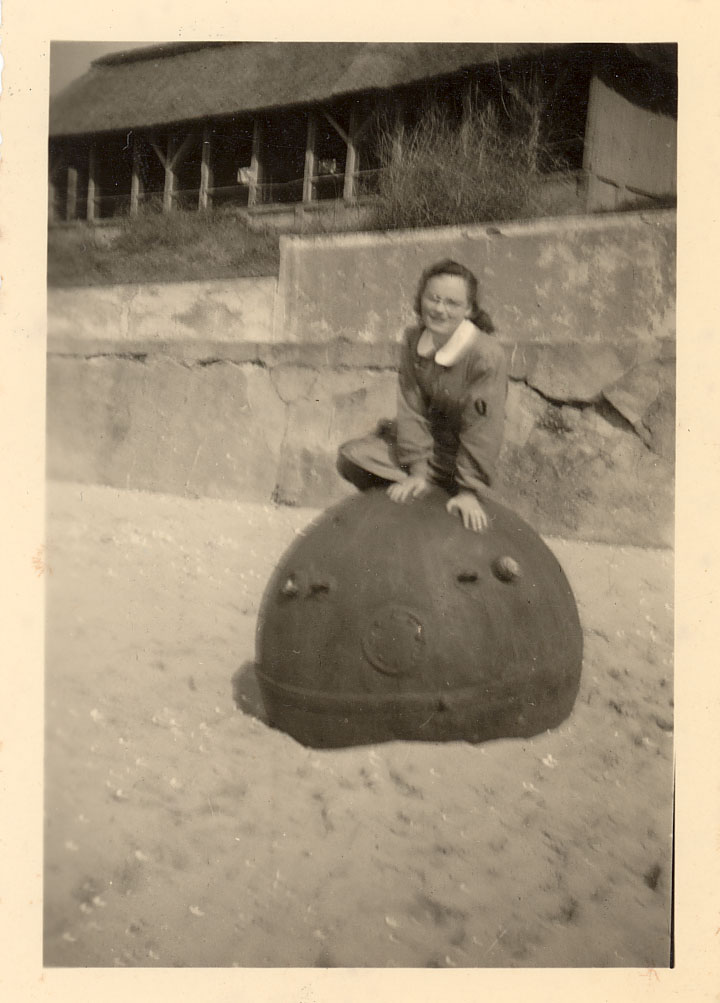

Fig. 11. Edeltraud Radack at the beach sitting on a defused sea mine. (K. Radack Siebach)

Fig. 11. Edeltraud Radack at the beach sitting on a defused sea mine. (K. Radack Siebach)

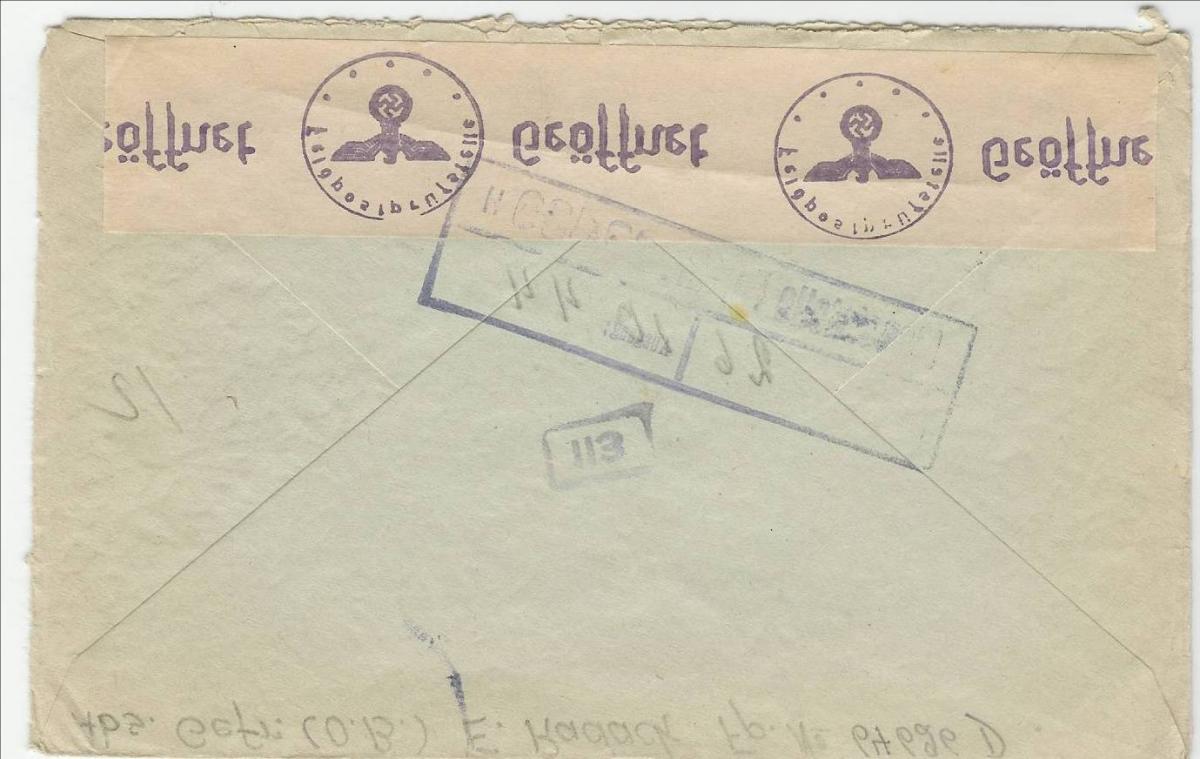

Fig. 12. The envelope carrying Ehrenfried Radack’s letter home to his parents was opened by censors. The stamp (geöffnet, “opened”) attests to the process. (R. Radack)

Fig. 12. The envelope carrying Ehrenfried Radack’s letter home to his parents was opened by censors. The stamp (geöffnet, “opened”) attests to the process. (R. Radack)

The of Ehrenfried Radack’s military service during the war (just sixteen months) was very short compared to his time as a POW in the Soviet Union. Year after year dragged by for the young man as he battled to stay healthy, all the while longing for home. Two letters written to his family in Kiel reflect his thinking in the last months of his incarceration:

February 15, 1949:

My beloved ones, next month it will be four years since my last farewell to you. I remember it so well. Who would have realized then that our reunion would be so far away and still not even know when the time will come. . . . It is difficult to preserve the spiritual and moral strengths, but if I didn’t have any faith and all you have taught me, I would have turned out to be like everybody else. . . . Here I have to live the life how it is in reality but still preserve my own dignity. [15]

June, 1949:

I look forward to be together with you again. Many things will have changed at home in the four years I was gone. . . . I, too, have changed, more matured by the hard and true face of life. It has pulled me away from the dream world of my youth for life into an unmerciful period of time. But this has given me strength and knowledge and faith and the desire to always choose the right. . . . I know our Father in Heaven will hold his protecting arm around me until we meet again. [16]

In August 1949, still in only his twenty-fourth year, he was released from captivity in the Soviet Union and returned to his family in Kiel. He was one of the last Latter-day Saints of the West German Mission to come home after the war, but he had seen enough death in the camps to know that many other German soldiers would never come home.

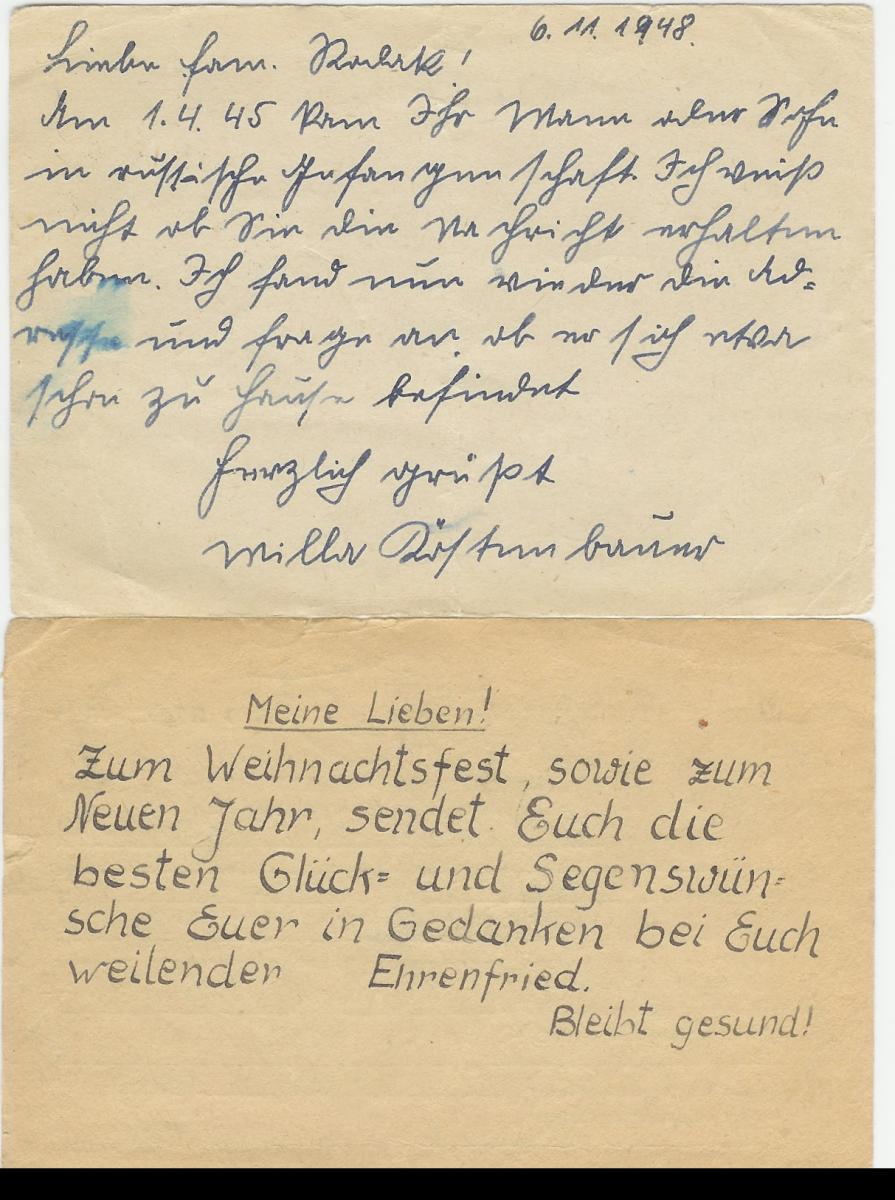

Fig. 13. This card was sent by German POW Milla Köstenbauer to the Radack family in Kiel in 1948: “I don’t know if you have been informed that your son was taken prisoner by the Russians. Or is he already home again?” (R. Radack)

Fig. 13. This card was sent by German POW Milla Köstenbauer to the Radack family in Kiel in 1948: “I don’t know if you have been informed that your son was taken prisoner by the Russians. Or is he already home again?” (R. Radack)

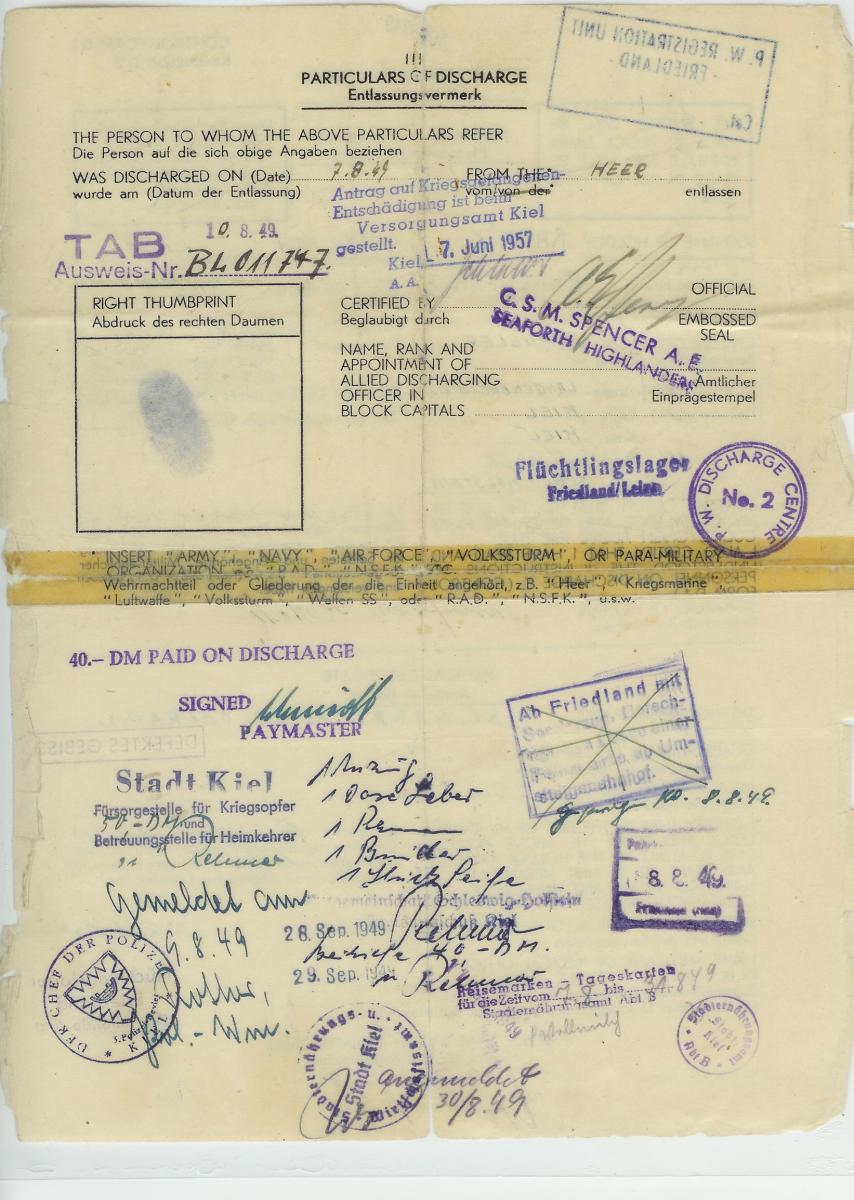

Fig. 14. The release papers for POW Ehrenfried Radack in 1949. (R. Radack)

Fig. 14. The release papers for POW Ehrenfried Radack in 1949. (R. Radack)

In Memoriam

The following members of the Kiel Branch did not survive World War II:

Walter Erich Baron b. Breslau, Schlesien, 15 May 1919; son of Alfred Fritz Baron and Meta Klara Cäcilie Kosalek; bp. 17 Dec 1935; conf. 17 Dec 1935; k. in battle (CHL microfilm 2458, Form 42 FP, pt. 37, all-mission list 1945–46, 170–71; CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 489; IGI)

Paula Johanna Christine Anna Dibbert b. Regensburg, Oberpfalz, Bayern, 4 Jul 1888; dau. of Johannes Peter Detlef Dibbert and Johanna Christine M. Dibbert; bp. 24 Jul 1929; conf. 24 Jul 1929; m. —— Kol; d. nerve condition 17 May 1941 (CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 314; IGI)

Max Wilhelm Friedrich Drews b. Trassenheide, Usedom, Pommern, 6 Sep 1884; son of Johann Karl Friedrich Drews and Marie Wilhelmine Friederike Lewerentz; bp. 23 Dec 1922; conf. 23 Dec 1922; m. Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein 17 Nov 1906, Emma Ottilie Emilie Schmalz; 4 children; d. heart condition Pahlhude, Dittmarschen, Schleswig-Holstein, 29 July 1945 (CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 86; FHL microfilm no. 25757, 1925, 1930, 1935 censuses; IGI; AF)

Rudolph Paul Heinz Otto Haak b. Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein, 15 Mar 1924; son of Konrad Friedrich Heinrich Haak and Marie Louise Niehus; bp. 4 Jun 1932; conf. 5 Jun 1932; ord. deacon 9 Apr 1939; navy lieutenant; k. in battle near Essel, Hannover, 12 Apr 1945; bur. Essel, Germany (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, all-mission list 1938–45, 137–38; CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 118; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Anni Sophie Katharina Hutzfeldt b. Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein, 2 Feb 1913; dau. of Waldemar Ludwig Hutzfeldt and Emma Eliese Dorothea Schlueter; bp. 10 Nov 1923; conf. 11 Nov 1923; m. 9 Mar 1935, Waldemar Claussen; k. air raid Kiel (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, all-mission list, 1945–46, 170–71; CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 132; IGI)

Hermann Gustav Jahn b. Landsberg/

Dorothea Henriette Friedericke Japp b. Altona, Schleswig-Holstein, 29 Jan 1866; dau. of Christian Heinrich Japp and Elisa Anna Marg Grammerstorf; bp. 16 Apr. 1920; conf. 16 Apr 1920; m. 17 Oct 1885, Ludwig Jürgens; d. old age 15 Sep 1943 or 15 Dec 1944 (CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 147; FHL microfilm 271375; 1930 census; IGI; AF; PRF)

Hans Krämer b. 3 March 1909; k. Russia July 1942 (Marlies Radack Krämer)

Wilhelmine Kroll b. Schmoditten, Pr. Eylau, Ostpreußen, 14 May 1864; dau. of Wilhelmine Kroll; bp. 13 Sep 1927; conf. 13 Sep 1927; m. August Simon; d. old age 28 Jul 1941 (CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 281; FHL microfilm 245265; 1935 census)

Herbert Fritz Karl Kuhr b. Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein, 16 Mar 1914; son of Heinrich Wilhelm Kuhr and Betty Emilie Jansen; bp. 5 Jun 1923; conf. 5 Jun 1923; ord. deacon 1 Jun 1930; lance corporal; k. in battle by Wesel, Rheinland, 26 Mar 1945; bur. Mönchengladbach-Haardt, Germany (CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 154; FHL microfilm 271381; 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses; www.volksbund.de; IGI, AF, PRF)

Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Metelmann b. Diepholz, Hannover, 22 Sep 1874; son of Johann Heinrich Hans Asmus Metelmann and Sophie Marie Elisabeth Dohse or Fahse; bp. 7 Jun 1930; conf. 8 Jun 1930; ord. deacon 19 Oct 1931; ord. teacher 2 Oct 1932; ord. priest 2 Dec 1934; ord. elder 17 May 1936; m. 17 Oct 1899, Fanny Wilhelmine Butenschön; k. air raid 24 Jul 1944 (CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 334; FHL microfilm 245232; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Helmut Evan Reinhold Radack b. Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein, 28 Apr 1912; son of Friedrich Wilhelm Gustav Ernst Radack and Rosa Christine Larsen Winter; bp. 21 Dec 1924; conf. 21 Dec 1924; d. 15 May 1941 (CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 216; FHL microfilm 271398; 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Wilhelm Rosenkranz b. Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein, 24 Oct 1915; son of Johannes Heinrich Rosenkranz and Ema Sophia Antoinette Schaar; bp. Kiel 8 Oct 1932; conf. 8 Oct 1932; ord. deacon 1 Oct 1933; ord. teacher 10 Nov 1935; corporal; k. in battle near Wichotwice or Leczyca, Poland, 9 Sep 1939; bur. prob. Siemianowice, Poland (Der Stern, Oct 1939, 372; www.volksbund.de; CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 418; IGI)

Therese Auguste Mathilde Sakolowski b. Elisabethsthal, Bütow, Köslin, Pommern, 14 Feb 1876; dau. of Wilhelm Erdmann Sakolowski and Karoline Wilhelmine Albrecht; bp. 10 Nov 1923; conf. 10 Nov 1923; m. 4 Nov 1899, Julius Kretschmann, div.; 2m. Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein, 2 Mar 1918, Wilhelm Heinrich Martin Geist; 3 children; d. lung and heart problems Kiel 12 Jan 1943 (CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 105; FHL microfilm 25773; 1925, 1930, 1935 censuses; IGI, AF)

Marie Dorothea Sievers b. Jevenstedt, Rendsburg, Schleswig-Holstein, 2 Jul or Sep 1865; dau. of Claus Sievers and Magdalena Nickels; bp. 25 Jun 1927; conf. 25 Jun 1927; m. —— Clausen; d. old age 5 Apr 1942 (CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 34; IGI)

Johann August Weiss b. Dirschau, Westpreußen, 15 Aug 1894; son of Henrietta Jantczel; bp. 20 Sep 1924; conf. 20 Sep 1924; m. Anna Wischnewski; d. stroke 29 Apr 1941 (CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 269; FHL microfilm no. 245296; 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses)

Rosa Christine Larsen Winter b. Haderslev, Haderslev, Denmark, 9 May 1865; dau. of Jens Larson Winter and Petruline Lund; bp. 8 or 9 May 1898; conf. 9 May 1898; m. Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein, 2 or 21 Aug 1893, Friedrich Wilhelm Gustav Ernst Radack; seven children; d. old age Kiel 8 Dec 1939 (CHL microfilm 2448, pt. 27, no. 215; FHL microfilm 271398; 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Notes

[1] Karl-Heinz Goldmund to the author, May 3, 2009. Goldmund located the date in a history of the Kiel Branch as well as on a postcard.

[2] For details of the evacuation, see the West German Mission chapter.

[3] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[4] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[5] Ursula Leschke, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann, October 24, 2008.

[6] Kiel Branch History; copy courtesy of Karl-Heinz Goldmund.

[7] Karla Radack Siebach, interview by Russell H. Michael and Judith Sartowski in German, Alpine, UT, February 20, 2010, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[8] Ehrenfried Radack, sacrament meeting talk, 4–5; private collection.

[9] Karla is one of several Church members who remembered enemy bombers dropping toys that were actually booby traps and that severely injured children who picked them up.

[10] Ehrenfried Radack, “My Autobiography” (unpublished); private collection.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Marlies Radack Kramer, interview by Michael Corley, Sandy, UT, March 21, 2008.

[13] Radack, “My Autobiography.”

[14] Radack, sacrament meeting talk, 9.

[15] Ehrenfried Radack to Karl and Martha Radack, February 15, 1949; private collection.

[16] Ehrenfried Radack to Karl and Martha Radack, June 1949; private collection.