Herne Branch

Robert Minert, “Herne,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 364–370.

The Herne Branch was located in a city that lies between Essen and Dortmund. The 129 members of the branch were distributed throughout a city that numbered nearly one hundred thousand inhabitants when World War II broke out. In general, the Herne Latter-day Saint represented in their socioeconomic status the local society, dominated by blue-collar workers in industry and mining.

The branch met in rented rooms at Schäferstrasse 28. Helga Gärtner (born 1929) described the setting:

The Schäferstrasse was a little outside of the city center and we did not have to meet anywhere else during the war. The rooms were in the Hinterhaus. We entered the building in the back door and were then standing in a small room. From that small room, one could enter the large room in which we held our meetings. The bathroom was located upstairs and could be reached by a small staircase. Everything was kept very simple. We held all of our meetings in that large room since we did not have smaller ones to use. . . . It was all so simple but we were so happy. There were about twenty to thirty people in attendance on a good Sunday. . . . We even celebrated Christmas in those rooms. [1]

A missionary in Herne in 1938, George Blake of Vineyard, Utah, described the branch as “one of the strongest branches I worked with in Germany.” He recalled several members who were educated and strengthened the branch. With the departure of the American missionaries in August 1939, Franz Rybak was asked to lead the branch, which he did for the next nine years. According to the branch history, he was initially assisted by counselors Eugen Kalwies and Hermann Heider. [2] Other leaders of the branch in 1939 were Gustav Mellin (genealogy), Alma Domina (Primary), Fritz Gassner (music), and Augusta Ryback (Relief Society). [3]

According to the branch directory, the first meeting on Sunday was a teacher training class at 8:30 a.m. with Sunday School at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting at 7:00 p.m. Tuesday was a busy day in the branch, with the Relief Society meeting at 5:00 p.m. and a Bible study class (apparently replacing Mutual) at 7:00. The genealogy class met every fourth Tuesday at 7:00 p.m. The Primary met on Thursdays at 4:00 p.m., and an entertainment activity was scheduled for each Friday evening at 7:00 p.m.

| Herne Branch [4] | 1939 |

| Elders | 13 |

| Priests | 2 |

| Teachers | 1 |

| Deacons | 6 |

| Other Adult Males | 21 |

| Adult Females | 63 |

| Male Children | 12 |

| Female Children | 11 |

| Total | 129 |

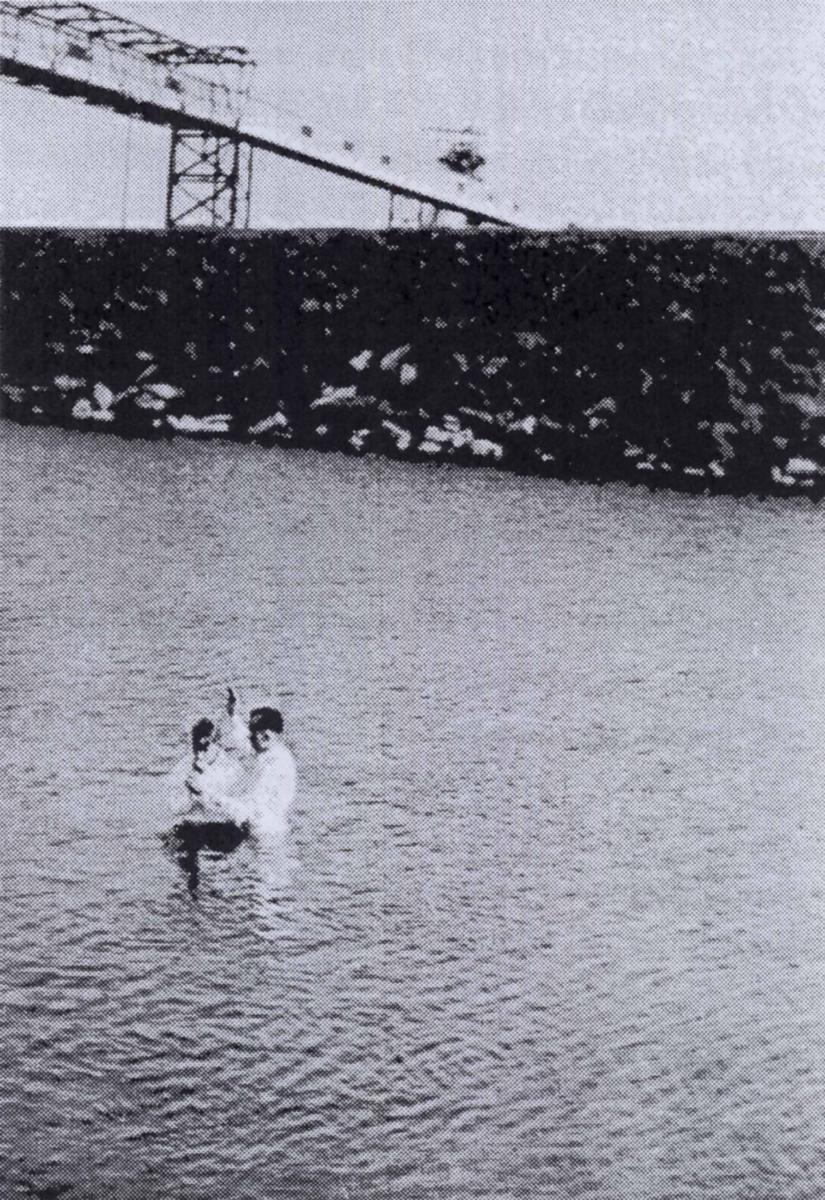

Fig. 1. A baptism in the canal by Herne in 1933. (H. Uhlstein)Edith Kalwies (born 1931)

Fig. 1. A baptism in the canal by Herne in 1933. (H. Uhlstein)Edith Kalwies (born 1931)

recalled being baptized in connection with a district conference in Essen:

Whenever there was a district conference there, people would be baptized because they had a baptismal font. All the children who had birthdays were baptized that day. It was December 17, 1939. My father was away in the service so I was baptized by Brother Ryback. We were confirmed by Brother [Christian] Heck, the [mission supervisor]. [5]

When the war began, Helga Gärtner was a new member of the Jungvolk. She had these recollections of the organization:

For us it was a wonderful program, similar to the Boy and Girl Scout program of today. Once a week, we would go to home evening. We were taught world history, of course with the emphasis on Hitler’s agenda. We were told to read his book, Mein Kampf, but I never did. I found it too boring. All I was interested in was the fun that was offered. . . . Once in a while they would take us to classic films. The best were the Shirley Temple films. She was our idol. The whole troupe would go downtown to a real theater as a group with our leader. After one year, we were given uniforms to wear. I loved going there for the fun and the friendships I made. [6]

In the midst of a crucial mining region, the city of Herne was subjected to constant bombardment from the air. Early in the war, Andreas Gärtner was drafted. Soon thereafter, his wife and their two children lost their apartment. Helga recalled that terrible night:

We had fled to the bunkers again one night. When my mother, my grandmother, my brother and I emerged the next morning, we all turned to look at our mother in shock. The sheer terror of the bombing and the realization that our home had received a direct hit and was gone, had paralyzed the left half of my mother’s face. She never regained any sensation to that half of her face to the end of her life. [7]

With her home in ruins, Emma Gärtner allowed her children to be sent away from Herne. Fortunately, both Helga and Reinhard (born 1933) were placed in homes in the small town of Urloffen, near Kehl in Baden. Helga described the experience in these words:

Reinhard and I were able to see each other during the school hours. My brother was so homesick and I was desperately sad for him. He missed our mother so much. We didn’t have an easy life either. After school we were required to earn our keep and do chores around the farm. In this little farming community, there was a trade school for nurses and we would serve as models of critically injured patients for them to practice on. [8]

Edith Kalwies and her siblings were likewise sent away from Herne. For nine months, they lived with various families in a small town near Weimar in Thuringia. Back home, it was decided that they should again be evacuated. The second time saw them in a hotel commandeered for their use in a town near Berchtesgaden in Bavaria. While there, an unusual event occurred—Adolf Hitler came to town. She recounted:

One day, somebody came running and said that Hitler was in the village. And they wanted all the youth groups there to put on our [Jungvolk] uniforms they had given us. Black skirt, white blouse, and a black kerchief. We were to assemble ourselves and walk down to the village where Hitler supposedly was visiting. I think he was paying a condolence call to a widow whose husband was a military officer who had been killed. There was a staff car and bodyguards, and there were quite a few of us, and we were half-circled around the house, and they told us to chant for him until he finally came out. He shook hands with a few who were right in the front and then waved his hand and said good-bye and took off in his car. I had actually seen Hitler with my own little eyes!

Fig. 2. The Herne Branch in 1939. (H. Ulstein)

Fig. 2. The Herne Branch in 1939. (H. Ulstein)

Andreas Gärtner was not happy when he learned that his children were separated from their mother. When the term of her Bavarian stay ended, Edith’s classmates all headed west for Herne, while little Edith boarded a train east to the home of relatives. Her journey took her hundreds of miles to East Prussia to a town near the city of Tilsit. It must have been a daunting expedition for such a little girl. “I had my little suitcase and a little sign around my neck with my name and my destination. They told the stationmaster to look out for me and call ahead to the stationmaster where I was supposed to go and let him know that a little girl was coming and to look out for me.” The destination was the farm of Brother Gärtner’s uncle, and Martha Kalwies was welcomed there with her children. On several Sundays, the Kalwieses were able to attend church meetings with the Tilsit Branch. It was a long walk that they sometimes made on Saturday evening in order to be on time the next morning. A single lady in the branch often took them in.

It was about 1942 when the Fritz Gassner family lost their home for the first time. They were living on Schäferstrasse not far from the branch rooms. Daughter Ingrid (born 1932) recalled the sight when she, her mother, and her brother emerged from their basement shelter when the all-clear sounded: “We looked up and the rooms above us were destroyed. We saw a woman who was severely injured by a piece of metal. My mother was able to get us out of there. It was scary.” [9] They found another apartment and were bombed out again. Finally, they returned to the Schäferstrasse and lived in the same building as the church rooms; that building survived the war.

Herbert Uhlstein (born 1934) had about as many exciting experiences as any boy could want—and several that were definitely unwanted. The first may have been the destruction of the apartment building in which his family lived. When a bomb struck the side of the building near the third floor, the inhabitants in the basement shelter could hear the structure begin to collapse. As was required all over Germany, a hole had been opened into the adjacent basement and closed again temporarily. Herbert recalled how it took only seconds to open the hole and move the fourteen persons (including his mother, his baby cousin, and himself) through a series of basements before emerging onto the street. He described what happened next in the commotion:

My mother was trying to hold her hands over my mouth [to keep the dust out] when the building collapsed. Our house and the house next to it were burning. I was carrying my baby cousin, and I ran right into a bomb crater in the street. A bomb had hit there and broken the water pipes, so it was already full of water and I fell into it. Thank goodness there was a gentleman right behind us; he jumped in and got us out. [10]

The aftermath of the air raids was a shared experience in wartime Germany. Herbert recalled being loaded onto trucks with other youth and taken to areas of the city where the youths were required to help rescue people trapped in basements and to recover bodies of the victims. “I found a man just standing there in a bombed-out building. He looked perfectly alive, and I hollered at him to come and get out of there. He fell over, and his whole back was burned from top to bottom. He was already dead.”

Fig. 3. Left to right: Herbert Uhlstein Sr., Herbert Uhlstein Jr., Andreas and Sara Gärtner (parents of Sara Uhlstein), and Sara Gärtner Uhlstein. (H. Uhlstein)

Fig. 3. Left to right: Herbert Uhlstein Sr., Herbert Uhlstein Jr., Andreas and Sara Gärtner (parents of Sara Uhlstein), and Sara Gärtner Uhlstein. (H. Uhlstein)

Herbert learned how to survive in wartime, but he had a hard time understanding certain political concepts, such as the Nazi treatment of the Jews: “My best friend was Jewish. I played with him and grew up with him. One afternoon we were playing together, and the next day they took him away. I couldn’t understand why he hadn’t said good-bye. I asked my mother why and a lot of questions. She tried to explain it to me.”

Heinrich Uhlstein was already in uniform at the time and therefore could not help his wife and son find another place to live. Fortunately the family of Gustav Mellin (also members of the branch) took them in for the next few weeks. About a year later, the government wanted to send Herbert to Hungary as part of the Kinderlandverschickung program, but Sister Uhlstein resisted. The Uhlsteins may have escaped some of the unpleasant aspects of life in Nazi Germany, but another threatened them in 1944: Herbert turned ten and was to be inducted into the Jungvolk program. His parents were distinctly anti-Hitler and would gladly have kept Herbert away from that influence. He recounted the story:

First we got letters and then I had to do a lot of fibbing. I wasn’t going to tell them the truth because my mother would be in trouble. Then two Nazi soldiers came and took me away to be interrogated. They had me in that room for quite a while. I was really scared. I told them that my mother didn’t want me to go [to Jungvolk activities] because I was skinny and frail. After that, we took off and went to Erfurt.

Sister Uhlstein took Herbert to the home of relatives near Erfurt in central Germany, where they stayed for about ten months. She had already received notice that her husband was missing in action, and she must have felt very lonely and discouraged. In any case, they had escaped the Jungvolk leaders and were safe in a relatively peaceful part of Germany.

Helga and Reinhard Gärtner stayed in Urloffen for three years, and though they were visited only once by their mother, they wrote many letters. Back in Herne, Emma Gärtner and her mother had moved into a small cabin on a garden property at the outskirts of town. In 1944, the children were finally allowed to return home and were taken in at the garden property. Helga viewed the devastation of her home town but was pleasantly surprised by one thing:

The Schäferstrasse was still intact and the meeting rooms were not damaged. It was astonishing, but we still met regularly on Sundays and everything seemed to be just the same. The only change we noticed was that the attendance declined during the war years, but that was something we knew would happen. I am not sure if we always had enough priesthood holders during the war [because I was gone] but I know that some elderly brethren and sisters were still there.

Ingrid Gassner joined the throngs of children being evacuated from Herne in 1944. The destination for her class was near Bratislava in Czechoslovakia. Gone for nearly three years in all, she was also housed in locations near Prague and in Passau, Bavaria. Because Fritz Gassner suffered from a kidney ailment, he was not drafted. He and his wife were even able to visit their daughter on one occasion. The government’s youth programs were in full swing where Ingrid was, as she explained:

The Jungmädel program taught us cleanliness and exercise and good manners. We knew we had to keep our rooms in order. . . . Our leaders taught us the basic way of life. I wasn’t really homesick while I was gone because we had our teacher with us and we knew our classmates. But I was isolated from the Church and never had an opportunity to attend meetings.

Ingrid and her company were moved farther west as the war drew to a close and the Soviet Army approached from the east. By the time the end of the war came, they were in territory conquered by the Americans. Somehow, they found rail transportation and made their way safely home.

When the Red Army invaded East Prussia in the fall of 1944, Martha Kalwies realized that she needed to take her children and head west. She made a small backpack for each child and filled it with clothing, shoes, and a favorite toy. As Edith recalled, “The German troops were retreating column by column, and most of the populace was on the road. We heard that the Russians had already broken through.” Sister Kalwies was most fortunate to rescue her children from that dangerous situation. By the end of the war, they were back in Herne. Andreas Kalwies was reported missing in action, but it was eventually reported that he was a POW of the Americans. The family had lost their apartment and nearly all of their earthly possessions, but when Brother Kalwies returned several years after the war, they were at least all together and healthy.

Like Sister Kalwies, Sara Uhlstein had no desire to be in the path of the invading Soviet soldiers. She took Herbert one day and began the trek west to Herne, nearly two hundred miles away. They walked with thousands of refugees. When it was clear that they did not know which way to go, Sister Uhlstein took her son into the forest, where they knelt and prayed for guidance. Then she announced that she knew which way to go. They soon crossed over railroad tracks, and she told her son that they were to follow the tracks. “When I saw that the tracks were unused and the weeds two feet high, I told her, ‘Mother, no train is coming down this track. It hasn’t been used for a very long time!” Nevertheless, they went where she directed, and eventually a train did come. It was a military transport that had been rerouted due to a damaged main line. The two jumped aboard and rode with the soldiers until enemy planes attacked the train. Later, they found a ride on some trucks, did a lot of walking, and arrived safely in Herne.

Their return was safe, but being in Herne again was fraught with danger. In the last months of the war, Herbert Uhlstein and his mother spent more and more time standing in line to get food from stores with ever-decreasing supplies. On one such day, Herbert was in one line and his mother in a second when a potentially disastrous incident occurred, as he recalled:

It was right before the end of the war when the enemy was shelling the town with artillery. They hit the house across the street from where my mother was in line. The shrapnel came flying and hit her right on the side of her hip where she carried her canister with a gas mask in it. It hit that steel canister and flattened it. Those canisters were really well built. The blow knocked her down, and she was sore for a long time. She had a big bruise, but nothing was broken.

Fig. 4. Members of the Herne Branch during World War II. (H. Ulstein)

Fig. 4. Members of the Herne Branch during World War II. (H. Ulstein)

When the British occupied Herne in 1945, Franz Ryback’s apartment was searched and the branch funds were confiscated. Soon after that incident, he appeared in the office of the British commandant in the Herne city hall and informed the officer that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints enjoyed protected status under the Americans and that the confiscation of the branch funds was illegal. The commandant ordered that the funds be returned, and the branch was allowed to develop without restriction. [11]

With the war over, Helga Gärtner and many other Germans had to deal with the fact that Hitler had caused unspeakable things to be done. She recalled being told during the war that the Jews were Germany’s ruin and were simply being deported from Germany; she and other German youth believed those claims. When the truth about the murder of the Jews was uncovered after the war, she said, “We didn’t believe this at first because our leader always spoke of honor, goodness, and kindness and love of our fellowman.” [12]

The incessant bombings by the Allies killed only one member of the Herne Branch but drove many others from the city for years at a time. At least six men died in combat. It would have been easy at the end of the war to give in to despair, but the Latter-day Saints in that battered city did not. Their meetinghouse still stood, and they gathered in increasing numbers as the dust of war settled.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Herne Branch did not survive World War II:

Auguste Bweski b. Pierlafkin, Ostpreußen, 19 May 1885; dau. of Martin Bweski and Gottliebe Librida; bp. 12 May 1909; conf. 12 May 1909; m. Adolf Starbatti; k. air raid 11 Nov 1944 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 114; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 362; FHL microfilm 245273; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Julie Auguste Dobrzinski b. Barloschken-Neidenburg, Ostpreußen, 1 Dec 1885; dau. of Frieda Dobrzinski; bp. 4 Sep 1927; conf. 4 Sep 1927; m. 19 Nov 1905, August Jedamski; d. stomach cancer 2 May 1943 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 166)

Egon Drawe b. Herne, Westfalen, 10 May 1939; son of Wilhelm Gottlieb Drawe and Marie Anna Müller; d. lung sickness or lung operation 6 Mar 1940 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 147; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 840; IGI)

Wilhelm Gottlieb Drawe b. Herne, Westfalen, 11 Aug 1900; son of Heinrich Christoph Christian Drawe and Karoline Justine Kijewski; bp. 14 Nov 1937; conf. 14 Nov 1937; m. Herne 19 Oct 1928, Marie Anna Müller; 7 children; d. stomach surgery Castrop-Rauxel, Westfalen, 15 Jul 1940; bur. Herne 18 Jul 1940 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 32; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 777; FHL microfilm 25757, 1935 census; IGI, PRF)

Elfriede Berta Heider b. Husen-Kurl, Westfalen, 10 Jan 1913; dau. of Hermann Karl Heider and Paulina Anna Schwabe; bp. 12 Jul 1921; conf. 12 Jul 1921; m. 9 Aug 1932, Otto Hellmich; d. stroke 21 Sep 1940 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 61; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 505; FHL microfilm 68803, no. 505; FHL microfilm 162780; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Hermann Karl Heider b. Ober Peilau, Schlesien, 4 Nov 1873; son of Pauline Anna Heider; bp. 28 Jul 1920; conf. 28 Jul 1920; ord. deacon 10 Sep 1922; ord. teacher 1 or 2 Mar 1925; ord. priest 31 Jan 1926; ord. elder 6 Jun 1933; m. 3 Nov 1895, Pauline Anna Schwabe; d. stroke 5 Nov 1941 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 52; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 110; FHL microfilm 162780; 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Gerlinde Waltraut Hoffmann b. Herne, Westfalen, abt 1941; dau. of Emil Hoffmann and Klara Franziska Mixan; d. abt 1941 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 198; IGI)

Eugen Walter Kalwies b. Herne, Westfalen, 24 Feb 1934; son of Eugen Kahlwies and Martha Maria Rasavski; bp. 19 Apr 1942; conf. 19 Apr 1942; d. Argenfelde, Tilsit, Ostpreußen, 20 Sep 1943 (FHL microfilm 68803, no. 677; FHL microfilm 271376; 1930 and 1935 censuses)

Gerhard Günther Klein b. Herne, Westfalen, 17 Nov 1934; son of Karl Jakob Wilhelm Klein and Elfriede Sophie Waschke; d. spinal meningitis 30 March or 5 Apr 1940 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 71; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 769; IGI; AF)

Maria Kruska b. Awayden, Sensburg, Ostpreußen, 30 Mar 1871; dau. of Karl Kruska and Marie Duda; bp. 25 Jan 1925; conf. 25 Jan 1925; m. Aweyden, Sensburg, Ostpreußen, abt 1892 or 22 Feb 1900, Michael Nadolny or Nadolmy; 3 children; d. stroke Awayden 1 Mar 1943 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 99; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 234; IGI)

Kurt Walter Müller b. Kappel, Chemnitz, Sachsen, 12 Sep 1900; son of Robert Wendelin Müller and Anna Maria Boeckel; bp. 28 Jul 1926; conf. 28 Jul 1926; m. 3 Jun 1922 or 19 Oct 1928, Marianne Hildegard Uhlig; d. stomach cysts or tumors 14 Jul 1941 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 174; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 230; FHL microfilm 68803, no. 230; IGI)

Egon Anton Rutrecht b. Börnig, Herne, Westfalen, 24 Nov 1920; son of Anton Rutrecht and Martha Marie Lau; bp. 1 Jun 1929; conf. 1 Jun 1929; ord. deacon 6 Jun 1933; stormtrooper; k. in battle Mischkino, south of Leningrad, Russia, 13 Feb 1943 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 106; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 499; FHL microfilm 271408; 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Karl Heinz Rybak b. Recklinghausen, Herne, Westfalen, 9 Nov 1919; son of Franz Rybak and Auguste Konetzka; bp. 23 Jul 1928; conf. 23 Jul 1928; ord. deacon 6 Jun 1933; k. in battle 20 Dec 1941 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 110; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 438; FHL microfilm 271408; 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Fritz Gustav Semrau b. Herne, Westfalen; or Nekla, Posen, 26 May 1920; son of Hermann Emil Semrau and Marie Martha Hildebrandt; bp. 14 Jun 1928; canoneer; d. field hospital 239 by Stadniza, 10 km south of Semljansk, Voronezh Woronesh, Russia, 24 Aug 1942 (Semmrau; FHL microfilm 245261; 1925, 1930, and 1935 censuses; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Karl Theodor Spittank b. Sodingen, Herne, Westfalen, 6 Nov 1910; son of John Otto Spittank and Ida Wilke; bp. 27 Jun 1931; conf. 27 Jun 1931; m. 12 Feb 1934, Franziska Skrycak; corporal; k. in battle Babiza 27 Jan 1944; bur. Glubokoje, Belarus (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 181; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Heinrich Herbert Uhlstein b. Herne, Westfalen, 15 Apr 1909; son of Christian Max Uhlstein and Johanna Karolina Weis; bp. 2 Nov 1924; m. Herne 24 Dec 1931, Sara Gärtner; d. Witebsk, Russia, 30 Jun 1944 (IGI; FHL microfilm 245289; 1935 census)

Karl Heinz Friedrich Vahrson b. Herne, Westfalen, 13 May 1916; son of Karl Heinrich Otto Vahrson and Anna Martha Maria Meier; bp. 8 Aug 1926; conf. 8 Aug 1926; k. in battle or d. Herne 12 Mar 1945 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 126; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, all-mission list 1943–46, 186–87 and district list, 202–3; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 387; FHL microfilm 245289; 1925, 1930, and 1935 census; IGI)

Auguste Elfriede Liesette Wilke b. Langendreer, Westfalen, 15 May 1870; dau. of Andreas Wilke and Wilhelmine Menthof; bp. 19 May 1930; conf. 19 May 1930; m. 19 Sep 1903, Wilhelm Haarhaus; d. heart failure 15 Jun 1942 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 157; CHL microfilm 2447 pt. 26 no. 550; IGI)

Julia Zỳwitz b. Schönwiese, Saalau; or Heilsberg, Ostpreußen, 15 Mar 1866; dau. of Johann Zỳwitz and Julia Schimitzki; bp. 18 Aug 1914; conf. 18 Aug 1914; m. 10 Mar 1917, Wilhelm Chmielewski; d. pyelitis 1 May 1944 (FHL microfilm 68796, no. 27; CHL microfilm 2447, pt. 26, no. 53; FHL microfilm 25739; 1925 and 1930 censuses; IGI)

Notes

[1] Helga Gärtner Recksiek, interview by Michael Corley in German, Salt Lake City, December 12, 2008; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[2] Hundert Jahre Gemeinde Herne (Herne Ward, 2001).

[3] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[4] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[5] Edith Kalwies Crandall, telephone interview with Judith Sartowski, May 6, 2008.

[6] Helga Gärtner Recksiek, “My Book of Remembrance” (unpublished autobiography); private collection.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ingrid Gassner Schwiermann, telephone interview with the author, November 30, 2009.

[10] Herbert Uhlstein, interview by the author, Bountiful, Utah, June 20, 2006.

[11] Hundert Jahre Gemeinde Herne.

[12] Helga Gärtner Recksiek, “Book of Remembrance.”