Hamburg District

Roger P. Minert, “ Hamburg District, West German Mission,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 127–38.

Hamburg had more than 1.7 million inhabitants when World War II began and was thus the largest city in the West German Mission. Three branches existed there at the time—St. Georg, downtown; Barmbek, in the eastern part of the city; and Altona, in the western part. Nearly one thousand Saints belonged to those three branches. No other city in the mission had more than one branch in 1939.

| Hamburg District [1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 71 |

| Priests | 24 |

| Teachers | 24 |

| Deacons | 54 |

| Other Adult Males | 147 |

| Adult Females | 527 |

| Male Children | 55 |

| Female Children | 47 |

| Total | 949 |

Fig. 1. The Hamburg District consisted of three branches in the city of Hamburg and three more close by.

Fig. 1. The Hamburg District consisted of three branches in the city of Hamburg and three more close by.

When the war began, the district president was Alwin Brey (born 1902), a real estate agent dealing with nautical properties. His counselors were Paul Pruess of the St. Georg Branch and Friedrich Sass of the Lübeck Branch. Their church responsibilities included three branches in other cities: Glückstadt (twenty-five miles northwest of Hamburg), Lübeck (thirty miles northeast), and Stade (eighteen miles to the west). Direct connections via railroad made it convenient for Elder Brey and his counselors to visit the outlying branches and for the Saints from those towns to attend district conferences held every six months in the rooms of the St. Georg Branch in Hamburg.

Alwin Brey was drafted into the German navy at the end of 1941. His first counselor, Paul Pruess, was not in good health, so second counselor Otto Berndt (born 1906) temporarily assumed the leadership of the district. Counselor Friedrich Sass had been drafted into the Luftwaffe and was also no longer able to serve. Otto Berndt had done a short stint in the Luftwaffe but had spent so much time in hospitals with minor illnesses that he was classified as unfit for duty and sent home. He admitted that his health was not seriously impaired, but the change in status allowed him not only to avoid military service for the duration of the war but also to travel without restriction—both evidences to him of God’s protecting hand. In any case, it was nice to be home in June 1941, when his wife was expecting their fifth child. President Berndt was able to find employment with a company making metal signs with enamel finishes. (He was able to produce one for the St. Georg Branch and proudly mounted it on the wall by the entrance to the rooms at Besenbinderhof 13a.) [2]

Fig. 2. Alwin Brey, the president of the Hamburg District in 1939, served later in the German navy. (I. Brey Glasgy)

Fig. 2. Alwin Brey, the president of the Hamburg District in 1939, served later in the German navy. (I. Brey Glasgy)

Perhaps the greatest challenge for Otto Berndt as the district president was the philosophical disagreement he had with Arthur Zander, president of the St. Georg Branch. Brother Zander was enthusiastic in his support of the Nazi regime—too enthusiastic, as far as President Berndt was concerned. However, it seemed more important to avoid open conflict that might damage the atmosphere of the St. Georg Branch and perhaps call down the wrath of Nazi Party leaders upon the Church. By 1942, there were problems enough for the Church due to the Helmuth Hübener incident (see below), but Arthur Zander was drafted that year, effectively negating the hostilities between him and Otto Berndt. [3]

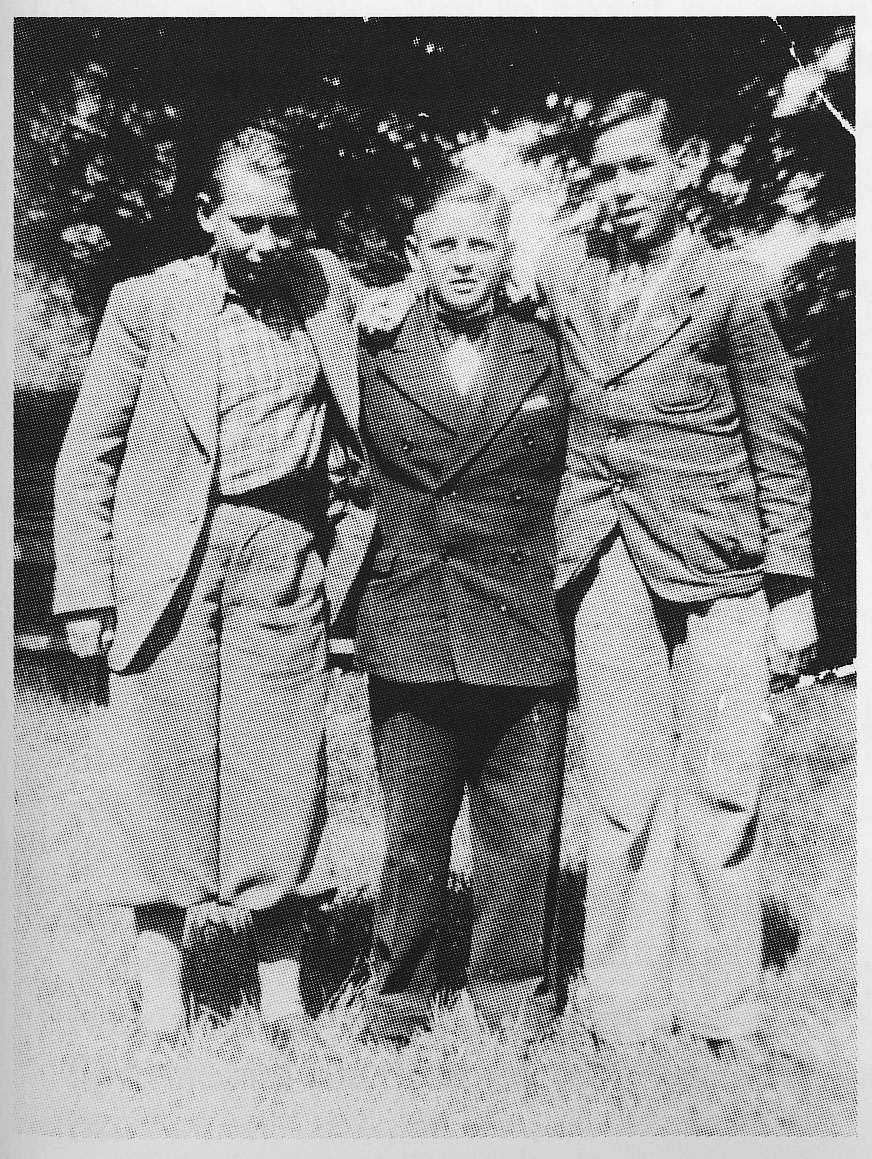

The case of the three teenagers of the St. Georg Branch who were convicted of conspiracy to commit treason is by now quite well known. Helmuth Hübener (born 1925), Karl-Heinz Schnibbe (born 1924), and Rudi Wobbe (born 1926) were arrested, charged with conspiring to commit treason against the state, tried before Germany’s highest court, and punished. Their story has been told in great detail in several books and needs no elaboration here. Nevertheless, a history of the West German Mission during World War II is not complete without at least a short summary of this sad episode. [4]

Fig. 3. From left: Rudi Wobbe, Helmuth Hübener, and Karl-Heinz Schnibbe were all arrested for distributing antigovernment literature. (Blood Tribunal)

Fig. 3. From left: Rudi Wobbe, Helmuth Hübener, and Karl-Heinz Schnibbe were all arrested for distributing antigovernment literature. (Blood Tribunal)

By all accounts, Helmuth Hübener was a bright young man, wise and mature beyond his years. An excellent student bound for a career in government service, he came into possession of a radio in 1941 that enabled him to listen to news reports from the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). He quickly came to the realization that the German radio news reports were not telling the full story—especially regarding German military losses. In about July of 1941, he invited (on separate occasions) his two best friends, Rudi Wobbe and Karl-Heinz Schnibbe, to share his discoveries. Listening to BBC broadcasts was strictly forbidden, and the fact that Helmuth transcribed or summarized broadcasts and then typed them out for distribution around town was nothing short of treason in Hitler’s Germany. Karl-Heinz and Rudi (both of whom were convinced that Helmuth’s political observations were correct) were the runners who placed the handouts in telephone booths, in apartment house hallways, and even on bulletin boards in blue-collar neighborhoods of Hamburg. Copies of some sixty messages were produced and circulated, and the two runners knew from the beginning that they had to be extremely cautious in distributing the literature.

Unfortunately, Helmuth was not as cautious. Convinced of the righteous nature of his cause, he approached another young man at work with the request that he translate the political messages into French. Helmuth hoped that French forced laborers working in Hamburg’s factories could read the messages, many of which openly charged Hitler and the government of lying to the German people about the status of the war. Eventually, Helmuth was reported by suspicious coworkers to the foreman, who collected information for the Gestapo. Helmuth was arrested on February 5, 1942. His best friends were picked up just days later—Karl-Heinz on February 10 and Rudi on February 18. The president of the St. Georg Branch informed the branch members of Helmuth’s arrest and expressed his dismay in the fact that Helmuth had used the branch typewriter to produce his anti-Hitler messages. (Helmuth was the branch secretary, and the machine was kept in his apartment so that he could type letters to branch members away from home in military service.)

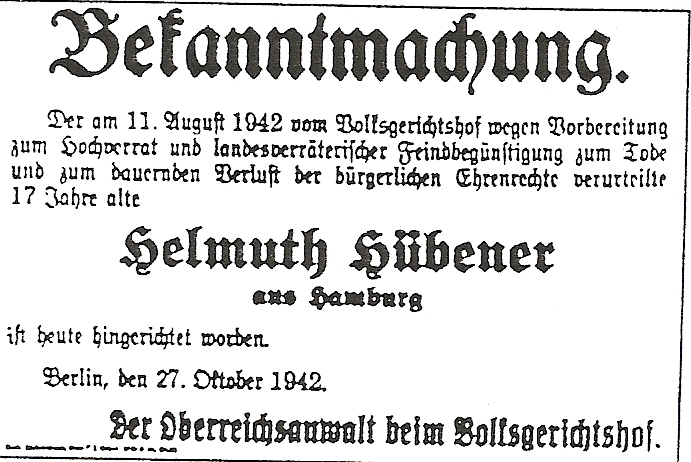

Fig. 4. This notice of Helmuth Hübener’s execution appeared in a Kassel newspaper. (J. Ernst)

Fig. 4. This notice of Helmuth Hübener’s execution appeared in a Kassel newspaper. (J. Ernst)

The three best friends were held in a local prison and interrogated for days in the Gestapo headquarters downtown. They had agreed in advance that if caught, they would do their best to shoulder the guilt individually and thus attempt to avoid burdening each other with guilt. Rudi and Karl-Heinz later wrote of the beatings they received and were both convinced that Helmuth had been formally tortured. In the meantime, the families of the three teenagers were questioned by the Gestapo, as were the presidents Arthur Zander and Otto Berndt. At first, the police could not be convinced that Helmuth could produce such sophisticated literature without the help of adults, but eventually they accepted his claim that he alone had written the messages.

The Gestapo theory that the boys had been enlisted by conniving adults was pursued aggressively, and district president Otto Berndt was summoned to Gestapo headquarters as part of the investigation. His description of the setting gives a clear picture of Hitler’s police state:

I rang the bell and the door opened automatically. The hallway was dark and there was nobody there. Suddenly, I heard a voice over the loudspeaker: “Come in. Take three steps forward!” which I did. The door closed behind me and I stood in the dark. Then a light went on and I saw a man sitting there; he took my papers. He wrote my name in a book, then handed me a piece of paper with a number on it and told me, “Sit on the chair with this number on it and wait until you are called. If you walk around or try to look into other rooms, you are breaking the law.” I went upstairs to the next floor and sat on the chair with the assigned number. I had not been waiting long when the door next to me opened and I was ordered to enter and take a seat. Until that moment, I had seen nobody but the man at the entry and all doors had opened and closed automatically. The building was like a mausoleum and I couldn’t hear anything. . . . It was creepy and I have to admit that my knees were shaking. I entered the room and it was empty except for two chairs and a table between them—that was the extent of the furnishings. A few files and a telephone were on the table. An official about thirty years old ordered me to sit down. I told him that while sitting in the hall I have been more afraid than at any other time in my life. . . . I felt the presence of evil and knew that I was in a dangerous situation and could not escape. Before entering the room I had said (“screamed” would be a better word for it) a quick prayer to my Heavenly Father. I cried for help from the depths of my soul; no sound escaped my tongue. When I sat down, all fear left me and I was encompassed by total peace. . . . I knew that God had heard my prayer and that I was under His protection. I noticed that a higher power had taken control over my body and this feeling stayed with me for four days—the duration of my interrogation. There is no other way to explain it; there is no other way that I could have answered all of those questions honestly and quickly and to the satisfaction of the Gestapo. [5]

In his recollection, Otto Berndt was questioned about the teachings of the Church, the relationship of the Church and the state, the philosophy of the Church regarding Jews, and several other topics.

In early August 1942, the three friends were transported by train to Berlin where their case was to be tried before the highest court of the land—a court famous for quick rulings and summary judgments against those who opposed the regime. The boys were provided defense attorneys who did their duty in a most perfunctory manner. The trial of all three began on August 11 and finished that very day. From the onset, Karl-Heinz and Rudi were convinced that a verdict of guilty was assured. Their sentences were indeed severe: Helmuth was sentenced to die; Rudi to spend ten years in prison; and Karl-Heinz, five years. Helmuth’s last statement to the judges inspired both Rudi and Karl-Heinz: “You have sentenced me to death for telling the truth. My time is now—but your time will come!” [6] The last two were soon transported back to Hamburg to prison, while Helmuth awaited the results of many appeals made in his behalf for clemency. All appeals were denied, and Helmuth Hübener was executed in Berlin’s Plötzensee Prison on October 27, 1942. [7] In the hours before his death, he wrote three letters to family and friends in Hamburg. Only one letter survives, in the possession of the Sommerfeld family; it includes this text:

I am very thankful to my Heavenly Father that this agonizing life is coming to an end this evening. I could not stand it any longer anyway! My Father in Heaven knows that I have done nothing wrong. . . . I know that God lives and He will be the proper judge of this matter. Until our happy reunion in that better world I remain your friend and brother in the Gospel. Helmuth. [8]

The reactions of fellow members of the St. Georg Branch were mixed. Most felt sorrow for the young men when their arrests and punishments were announced but were disappointed that such apparently foolish and self-destructive acts could be committed by Latter-day Saints who had been taught to obey laws and give allegiance to governments. Branch meetings were observed by government agents for some time after the incident, and the Church equipment used by Helmuth to produce the handbills was confiscated and not returned.

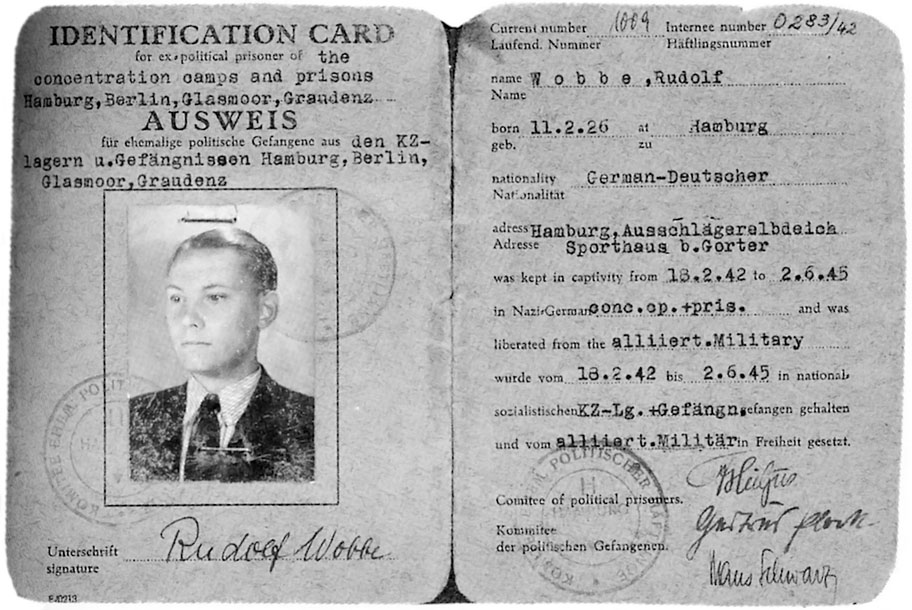

Rudi Wobbe and Karl-Heinz Schnibbe spent the next year in prison not far from Hamburg. The conditions of their incarceration improved a bit with time, but it was no happy existence. In December 1943, they were sent to occupied Poland and assigned to work in an aircraft repair factory. In January 1945, the Red Army streamed into Germany, and Rudi and Karl-Heinz were marched toward the west along with their fellow prisoners. They were back in the familiar surroundings of their Hamburg prison on February 16. Days later, Karl-Heinz was drafted into the German army and assigned to help stop the Soviet invasion in eastern Germany. Rudi was kept in Hamburg because he had a longer prison sentence to serve.

For the next three months, Rudi watched as more and more prisoners left to serve in the German army, but his own status as a political prisoner guaranteed him a longer stay in prison. It was not until late May that he and the last remaining prisoners were freed by French conquerors. The British occupation authority reviewed his story, were convinced of his innocence, and sent him home on June 2, 1945. He viewed with sadness the ruins of his hometown but was thrilled to see his family again after more than three years.

Fig. 5. Ruddi Wobbe’s identification card indicates that he was a political prisoner under the Nazis. (H. Schmidt Wobbe)

Fig. 5. Ruddi Wobbe’s identification card indicates that he was a political prisoner under the Nazis. (H. Schmidt Wobbe)

Karl-Heinz was captured by the Soviets in Czechoslovakia in April 1945 and spent the next four years in work camps in Russia. He suffered terrible illnesses, starvation, subzero temperature, mosquitoes, and the torture of being told repeatedly that “we would be going home soon.” After losing a dangerous amount of weight in April 1949, he was classified as unfit for work and sent back to Germany. Following a recuperative stay in a Göttingen hospital, he was released for good in June 1949 and returned to his family in a Hamburg that was finally beginning to rise from the ruins.

In the first few years of the war, the Allies had learned that a combination of explosive bombs and incendiary bombs could produce a disastrous effect known as “firebombing” in major German cities where wood structures were crowded around narrow streets. To be sure, the German military commanders knew this as well, but as the war dragged on, the German Luftwaffe became less and less able to defend the homeland. In July 1943, the British and American bomber forces in England decided that the city of Hamburg should be subjected to an intense campaign of raids within just a few days. Explosive bombs were to be dropped first to burst roof surfaces, doors, and windows, after which incendiaries would be dropped to start fires in the open structures. Four major attacks were carried out on July 25, 28, and 30, and August 3, and the proposed results were achieved—Hamburg burned for days. The heat was so intense and the fires so widespread that thousands died in air-raid shelters of suffocation without being so much as singed by the flames.

In his detailed study of the results of the air war against Hamburg, Hans Brunswig presented information collected by the Hamburg harbor weather service showing that the firestorm produced by the attacks resulted in flames soaring more than four miles into the sky, fed by winds of more than fifty miles per hour (winds caused by the fires sucking oxygen from ambient air on the ground level). [9] Following the success of these attacks, firebombings were carried out against many other German cities, the prime example being the attack of February 13–14, 1945, on Dresden. [10]

The following figures illustrate the extent of the losses in Hamburg during the entire war (about 80 percent of the damage occurring in July 1943):

Results of the Allied air war against Hamburg, Germany [11]

| Air-raid warnings sounded | 778 |

| Air-raid warnings with enemy airplanes sighted | 702 |

| Attacks | 213 |

| Airplanes involved in those attacks | Approx. 17,000 |

| Explosive bombs dropped | Approx. 101,000 |

| Incendiary bombs dropped | Approx. 1,600,000 |

| Bombs not effective (fell in water, etc.) | Approx. 50% |

| Deaths (male 41.8%, female 58.2%) | 48,572 |

| Deaths elsewhere from injuries in Hamburg | Approx. 3,500 |

| Apartments not damaged | 21% |

| Apartments with slight damage | 19% |

| Apartments with medium damage | 7% |

| Apartments with serious damage | 4% |

| Apartments totally destroyed | 49% |

| Apartments totally destroyed in all of Germany | 22% |

| Residents in Hamburg in 1939 | Approx. 1,700,000 |

| Residents with property loss | Approx. 1,170,000 |

| Residents with total property loss | 902,000 |

| Residents with partial property loss | 265,000 |

Among the residents and structures listed above were 790 Latter-day Saints, their homes, and their meetinghouses. The following accounts were provided by eyewitnesses regarding their experiences during the fire-bombings of July–August 1943.

With her husband serving as a soldier at the Eastern Front, Maria Niemann had recently given birth to a baby girl, and both of them had nearly died in the process. Just months after that trial, Maria’s family experienced the horror of the British attacks on Hamburg. Her son Henry (born 1936) was staying with a grandmother across town when the first bombings took place. As he explained, “They just bombed the living daylights out of this town. For hours we were in the basement and people were crying and carrying on and every once in a while you were . . . kind of lifted up in your seat because of the shock [of the bombs].” [12] Between attacks, Henry and his grandmother made their way through the fires and the rubble toward his home:

There were a lot of streets that we had to bypass because the walls of the apartments and the buildings collapsed into the street and you couldn’t get through . . . the narrow streets. . . . When we came to my street, there wasn’t anybody outside. All the windows were blown out through the shock and the bar tiles were off the roof. . . . I remember that I started crying and then I started running home.

Henry Niemann found his mother in her bed with his sister—both safe and sound. Maria Niemann recalled the following details about the attack that took place the next day:

I had to go with my children to the basement, and it was hard for me with a baby and my boy. . . . And so I had to call my neighbor. . . . She was a real good friend to me, and she helped and took the baby, and I took my son, and we went down to the basement. Then the bombs came down. It took our roof away, and here I was with a baby in a carriage and my son, and we had no roof. All the windows were out, and the curtains were hanging outside, and the water pipes were hit, and so there was gas mixed with water. What should we do? I cannot stay in my home with the baby. [13]

Fig. 6. and 7. The Zwick apartment at Süderstrasse 244 in Hamburg in 1939 and after the bombings of July 1943. Note the destroyed and abandoned streetcar. (F. Zwick)

Emerging from their basement shelter following one of those raids, Maria saw her city burning in every direction and the neighboring houses in ruins: “The sun was shining, but we didn’t see it. It was all black.” The three of them made their way out of town and were eventually fortunate to find lodgings in the town of Hude near the coast of the North Sea, about two hours northwest of Hamburg. According to Henry, they remained there for more than three years.

Gertrud Menssen survived the first few attacks with her two little children and found their home still standing. However, she feared that “the next time would be our turn.” She was right, and their home was totally destroyed during the night of July 27–28. Fortunately, her husband, Walter, just happened to be home on leave. In Gertrud’s recollection:

When we heard the bombers and bombs falling, we grabbed our children only and my purse with important papers—nothing else—and ran this time to the big bomb shelter on the corner under the school yard. I guess we just knew we would get it this time. While we were in the shelter, men would come in and call out the number of the houses that had been hit. And it did not take very long until they called #86 Hasselbrookstr. That was us! . . .When we finally got out of the shelter in the afternoon, the whole city seemed to be burning. It was so dark and smoky and frightening that we put wet hankies over the children’s eyes. Why cry about a household of furniture? . . . We were alive! And we were together! That was all that mattered. [14]

Walter Menssen got his family safely out of Hamburg and saw them onto a train to southern Germany before he was required to report for duty again. It would be more than a year before Gertrud and her (by then three) children would see Hamburg again.

During the worst hours of the raids over Hamburg, Gerd Fricke witnessed terrifying scenes: “I remember that when everything burned, the asphalt on the streets was like liquid, and the women with their children and strollers got stuck and burned to death right there. We saw many horrible things.” The Fricke family lost everything they owned for the second time. [15]

Although Rahlstedt was seven miles from downtown Hamburg, the bombs dropped on the city eventually struck Rahlstedt and the Pruess home there. Lieselotte Pruess (born 1926) recalled the tragedy that struck her family’s home in July 1943 while they were huddled in the basement:

My father had been outside watching things. Then he came into the basement and said, “We all have to get out right now! The house is on fire!” We had felt something hit the house, but in all of the commotion, we didn’t know what it was. So we ran out into the street and saw that our house was on fire. There was no fire department to help. Then my father and some neighbor men went back in to save some stuff. They brought our piano out too. The house burned to the ground, but we had our piano out in the street. I played the piano and then my sister played the song “Freut Euch des Lebens” [“Let’s All Be Happy”]. The neighbors remember that. [16]

The Pruess family evacuated to the town of Thorn in Poland, where they were given housing in some army barracks. Soon thereafter, Rosalie Pruess returned to Rahlstedt with a son, and they managed to make the home livable on a subsistence level.

Harald Fricke (born 1926) wrote the following account of the firebombings:

I was sixteen years old at the time. We (my mother, my sister Carla, my brother Gerhard, my Grandpa and I) were living at the time on Norderstrasse in [the suburb of] Hammerbrook. We survived the first attack in the basement shelter of our home even though the building above us was totally destroyed. Then we were assigned an apartment on Olgastrasse in the suburb of Rothenburgsort. This narrow street was destroyed one or two days later by the fires that spread throughout the city. Nobody could seem to escape the sea of flames anymore. We were fortunate to be in an apartment at the end of the street and were able to run through the hail of bombs and shrapnel across the street to the underground bunker at Brandhofer Schleuse. When we got there, they first didn’t want to let us in because the shelter was full and they were experiencing a lack of oxygen. . . . My darling aunt burned to death in a hospital. . . . Her son Herbert Fricke, a lieutenant in the Hermann Goering Guard Regiment, came home to Hamburg for a few days but he was unable to identify her among the many badly burned corpses. She was buried in a mass grave in Ohlsdorf. [17]

Perhaps the most trying challenge during the terrible air raids of July 1943 in Hamburg was to mothers with small children when the father was away in military service. So it was with Anna Marie Frank (born 1919) of the St. Georg Branch. She sought shelter in the basement of their apartment in the evening of July 27 with her daughter, Marianne (two years old), and her infant son, Rainer. As she anxiously awaited the all-clear signal a few hours later, Sister Frank and the others in the shelter knew that destruction was all around them. When the air-raid wardens opened the doors to the shelter and instructed them to hurry outside, everybody reached for blankets, soaked them in water, and threw them over their heads to prevent suffocation from smoke. Anna Marie Frank could not do this and simultaneously get her two children into the street and to safety, so her neighbors offered to take little Marianne with them. Tragically, when they emerged into the street, the chaos was such that Sister Frank lost sight of the neighbors. Amid the fires, the smoke, and the collapsing buildings, the neighbors and little Marianne disappeared and were never seen again. Anna Marie searched for months in city offices in vain for any trace of her daughter. [18]

District president Alwin Brey just happened to be home on leave from the navy when the firebombings struck his neighborhood. His daughter Irma (born 1926) recalled clearly what happened one night:

When the alarm sounded that [the British] were coming, we took our stuff that we had packed already and went down to the basement. When we came out, our building was almost completely flat. Our apartment was on the second floor and the inside was full of flames and it burned everything—our furniture and everything, but not just for us, but for everybody who lived in the building. So my dad took us out of the basement. Oh, there were so many dead people lying in the street, and they came with big trucks and picked them all up with forklifts. We were very lucky that my dad got us out. He got a car because he was an officer of the navy, and he got us in those bunkers. They couldn’t hurt them. We stayed there, I think, two or three days, and then a little further down off the bunker in the same street my uncle, my mother’s brother and his family lived there and they were all killed. Almost everybody on our street was killed, but we made it out alive. [19]

Alwin Brey was able to get his family out of town. They took a train south all the way across the country to the city of Bamberg, in Bavaria. After he found them a small room to live in, he returned to his station in France.

Young Inge Laabs (born 1928) recalled how people referred to Hamburg in July 1943 as “Gomorrah.” In her memory she could still picture many buildings burning for days because of the coal supplies in the basement. Her story illustrates the plight of tens of thousands of homeless people in that huge city in July 1943:

After we lost our home, we lived in an air-raid shelter for a while. When that was no longer possible anymore, we lived in damaged homes. We did not have much to eat and drink at all and could not brush our teeth. We had lost everything and wandered around trying to find a place to stay. Later on, we went to Pomerania (eastern Germany) where my grandparents lived. We could not stay very long because my mother had to return to her work and I to my work training. . . . The time we had to sleep in a railroad car in Friedrichsruh by Hamburg was the hardest. Sometimes, we couldn’t even get food with ration coupons. [20]

Arthur Sommerfeld had just returned from working in the Arbeitsdienst program when the firebombings began. He had received a severe head injury when hit by a falling tree and had not recovered entirely, but came to the rescue when the Sommerfeld apartment began to burn. His mother, Marie Friebel Sommerfeld, begged him to return to the apartment to retrieve their valued genealogical documents. While he was still in the rooms, a phosphorus bomb exploded, and he received burns on over 80 percent of his body. The documents were saved, but he was grievously injured. Fortunately, he survived. Sister Sommerfeld then received permission to evacuate her family to her hometown in the German-language region of Czechoslovakia. [21]

The Guertler family was on vacation in nearby Lübeck-Travemünde when the city of Hamburg was reduced to ashes in July 1943. Daughter Theresa recalled hearing her father describe what he found while on leave from the military after the bombing:

When he came to our street, he saw the house was totally destroyed. All that was standing was the chimney from the ground floor to the top floor, and on every level, there was a little kitchen corner attached to the chimney where the kitchen stove was still standing. That’s how he described it. So when he found out that the house was destroyed, he was hoping that we were in Travemünde, and we were, and then he told us that our house was destroyed. [22]

Figs. 6 and 7. The Zwick apartment at Süderstrasse 244 in Hamburg in 1939 and after the bombings of July 1943. Note the destroyed and abandoned streetcar. (F. Zwick)

Figs. 6 and 7. The Zwick apartment at Süderstrasse 244 in Hamburg in 1939 and after the bombings of July 1943. Note the destroyed and abandoned streetcar. (F. Zwick)

Fred Zwick (born 1933) was ten years old when the firebombings took place. He recalled clearly the night his home was destroyed:

We went to the bunker in the early evening and the air raids started, and I heard a lot of explosions. A lot of smoke was coming in through the vents. The reason was that there was a coal yard right next to it, and they had the coal stored right next to the walls of the bunker, and apparently it was set on fire. There was some water available, and the mothers and the adults, they tried to protect their children with wet blankets so we could breathe because the smoke was just very thick. Smoke from whatever. . . . We got out the next day about two o’clock. . . . Our apartment house was totally destroyed. A neighbor lady went to the basement to get the engagement ring of her daughter. She had suffocated but was still sitting at a table there. She was able to retrieve the ring, but as soon as she touched the hand it fell apart. [23]

Fig. 8. Otto Berndt in about 1937. (K. Ronna)

Fig. 8. Otto Berndt in about 1937. (K. Ronna)

Perhaps the most detailed and chilling account of the firebombing was written in 1963 by district president Otto Berndt. [24] With painstaking detail, he recounted the events of the night of July 27–28. As the air-raid warden of his apartment building, he was allowed to stay outside when the sirens wailed and during the subsequent bombing (which he was pleased to do, having a terrible fear of air-raid shelters). With the exception of his eldest daughter, who lived across town, his family was safe in a small village north of Berlin. Soon the apartment building was struck and started burning, but he was able to evacuate all of the occupants unharmed and send them on their way to safer locations. Then he attempted to help others. At one juncture, he ran into a shelter to help get the people out, thinking all the while of the many ways he could be killed in doing so. He was urged on by the thought that his own family might be in such a situation some day and that he would want others to rescue them. In the shelter, he found just one boy of about twelve years of age and quickly carried him outside, only to be told by first-aid personnel that the boy was already dead.

Returning to his neighborhood to determine the status of his home, he entered his apartment while the flames raged on the upper floors. He gathered critical personal items using sheets as bags and carried them down into the street. After about the fourth trip, he found that the bags in the street had caught fire. He then gave up any attempt to salvage more property and ran down the street as the fires spread from building to building. “All of a sudden, I felt an intense anger toward the pilots of the planes that had dropped the bombs,” he admitted.

An hour later, President Berndt came to a city canal and heard people on the other side screaming for help as the flames approached their position. There was no boat available to transport them to his side of the canal, so he found a rope. His idea was to swim across to their side and tie the rope around one person. Helpers on the safe side could then pull the person across while he swam alongside to assure that they did not drown. This he did stark naked, leaving his clothes on the safe side (hoping that sparks flying through air would not ignite them). He managed to help a number of women and old men across the canal for about an hour, then dressed and ran off in the direction of a safer neighborhood. “Not one of them thanked me,” he observed. As he ran between burning apartment houses, he saw in the street countless bodies of fire victims, most of which had shrunk to half their size when the heat removed the fluids from their bodies. When he accidentally touched several of them, “they disintegrated and returned to the earth as dust to dust,” he recalled.

At about six o’clock the next morning, when the sun should have been on the rise for the new day, Otto Berndt noticed that the clouds of smoke prevented any sunlight from illuminating the city. He had seen no firefighting personnel because the fires were everywhere and the streets were blocked with burned-out vehicles and furniture rescued from the apartments. Survivors were either fleeing for their lives or trying desperately to help others. At one point, he lay down and slept for an hour or two (time had seemed to be totally irrelevant that night) as chaos reigned round about. Sometime before noon, he found himself on a small boat being carried across the Elbe River to safety south of the harbor. His memories of the moment were clear years later:

As I sat on deck of the boat, I felt my apartment key in my pocket. I thought about the fact that I had once owned a beautiful apartment. Thirteen years of sweat and frugal living—all destroyed in a single night. The only thing I had left was this little key. Then I made a symbolic gesture by tossing the key into the Elbe, thereby separating myself totally from the past and entering into the present and the future. With no burdens, I stood at the threshold of a new life. Only God could know what it would bring.

President Berndt was united with his family in the village of Nitzow, and his daughter Gertrude joined them there. Exempt from military service, he could have stayed there in safety but felt that he must return to Hamburg to direct the Church there. Before he left Nitzow, he visited the East German Mission office in nearby Berlin and was able to purchase many Church books to replace the ones lost by the Hamburg Saints when they were bombed out. Back in Hamburg, the only place he could find to live was in a room in the building in which the Altona Branch held its meetings. He was still living there when the war ended.

An excellent but sad report was written by Hugo Witt, a member of the defunct St. Georg Branch, who made his way from his home in the Hamburg suburb of Wilhelmsburg to church in Altona on the Sunday after the worst of the air raids. This report was submitted to the mission office in Frankfurt on August 15, 1943:

Following a terrible war catastrophe, namely air raids by British and American planes over Hamburg-Altona, we were able after a short interruption to resume holding meetings in Altona, thanks to the mercy of the Lord, who preserved our meeting rooms. . . . I will try to describe a little of what I personally witnessed or heard about the catastrophe in Hamburg and how it has influenced the life of the Church in Hamburg:

In the night of Saturday–Sunday 24–25 July, Altona was attacked by a large number of airplanes dropping phosphorus, incendiary, and TNT bombs. I did not experience the worst of the attack because I lived out in Wilhelmsburg. When I made my way to Altona to Sunday School with my family, there were no streetcars in operation. The sun was darkened by the clouds of ashes from burning buildings in Hamburg. Then I made my way by bicycle toward the branch rooms in the Klein Western Strasse [37]. When I tried to cross the Elbe Bridge from Veddel toward Rothenburgsort, I found the way blocked. This compelled me to proceed via the road to Freihafen and over the new railroad bridge over the Elbe. All of the sheds were burning in Freihafen, and the path became increasingly difficult. My eyes started to burn from the smoke and the ashes. I was fortunate to make my way to the Messberg in relatively good time. Then my progress was slower and slower toward the downtown where many buildings were on fire. . . . It was almost impossible to ride my bicycle because so many people were fleeing. I then passed the harbor piers and made my way toward Altona. Here I had to climb over the rubble from the facades of buildings that had fallen onto the street. Along the way I had to carefully step around the bodies of the victims. At one point I counted 17 people, mostly women and girls. I finally reached the branch rooms, but of course there was nobody there. Then I went to visit the Thymian family, who lived across the street. Everything was chaos there because they had taken in refugees. There was a family with a two-week-old baby, and they were worried about the baby because there was so much smoke in the air. I stayed there for about 45 minutes. Before I left, Hyrum asked me to say a prayer, which I was pleased to do. Then I left.

I stayed with my family in Wilhelmsburg until Wednesday evening. Then we packed our things and followed the masses leaving Hamburg. They had been passing our house day and night with what little property they could rescue. We went to Göddingen and Bleckede on the Elbe and later with other members we went to Pörndorf near Landshut in Bavaria. Several weeks later I traveled back to Wilhelmsburg to continue my work in the factory. A week later I brought my family home. [25]

President Berndt had plenty of concerns to deal with in the spring of 1945. He had just succeeded in gathering his family members, who had been spread out over the map, and was living with several other refugee families in the rooms of the Altona Branch. The members of the three branches in the city of Hamburg were all meeting in the damaged rooms of the Altona Branch, but most of the Saints were no longer in Hamburg at all. Nevertheless, President Berndt held a district conference in April 1945, and at the conclusion of the conference, he did something quite different. According to his son Otto (born 1929):

My father said, Brothers and sisters, I feel that we should all hold hands throughout the congregation. Which we did, and we sang the hymn, “Gott sei mit euch bis aufs Wiedersehen” (“God Be With You Till We Meet Again”). I asked my father why we were holding hands. I didn’t understand the importance of it. He said to me, “I have the feeling that many of the brothers and sisters that we saw tonight in the meeting, we will never see in this life again.” He was right. . . . There were a lot of people there (they came from miles around)—despite the big hole in the ceiling. This is something that will be with me always. [26]

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[2] Otto Berndt, autobiography (in German, trans. the author) (unpublished, 1963), CHL MS 8316.

[3] Twenty years later, Otto Berndt made several distinctly critical statements about Arthur Zander, as he did about several other leaders of the West German Mission and the districts. It appears from his story that Otto Berndt expected that Church leaders should avoid any allegiance to Hitler’s government while they represented the Church. In other words, they should join him in condemning but not opposing the government.

[4] Two excellent versions in English were written by the principals of the story: Karl-Heinz Schnibbe with Alan F. Keele and Douglas F. Tobler, The Price (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1984) and Rudi Wobbe and Jerry Borrowman, Before the Blood Tribunal (Utah: Covenant, 1992). The best German account of the affair was written by Karl-Heinz Schnibbe, Jugendliche Gegen Hitler (Berg am See, Germany: Verlagsgemeinschaft Berg, 1991).

[5] Otto Berndt, autobiography.

[6] Both Rudi and Karl-Heinz recalled the quotation in very similar words. Both believed that Helmuth had been particularly bold in court in an attempt to absorb the majority of the guilt and thus draw attention away from his best friends.

[7] Helmuth was executed on the guillotine. The room (now empty) in which he died is a national monument to victims of National Socialist terror, and the three young men are listed among the many Germans who offered bona fide resistance to the government.

[8] Schnibbe, The Price, 58.

[9] Hans Brunswig, Feuersturm über Hamburg, 6th ed. (Stuttgart, Germany: Motorbuch Verlag, 1983).

[10] See the chapters on the Dresden branches in Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009).

[11] Brunswig, Feuersturm über Hamburg, 380–81, 383, 385, 401, 405.

[12] Henry Niemann, interview by Michael Corley, South Jordan, Utah, October 31, 2008.

[13] Maria Kreutner Niemann, “An Evening with Maria” (unpublished speech, 1988), transcribed by JoAnn P. Knowles, private collection.

[14] Gertrud Frank Menssen, autobiography (unpublished), private collection.

[15] Gerd Fricke, interview by the author in German, Hamburg, Germany, August 15, 2006; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[16] Liesellotte Pruess Schmidt, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, December 1, 2006.

[17] Harald Fricke, autobiography (unpublished, 2003), private collection.

[18] Anna Marie Haase Frank, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, October 27, 2006.

[19] Irma Brey Glas, interview by Michael Corley, Taylorsville, Utah, October 10, 2008.

[20] Inge Laabs Vieregge, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in Germany, October 2008.

[21] Werner Sommerfeld, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, January 19, 2007.

[22] Resa (Theresa) Guertler Frey, interview by Michael Corley, Salt Lake City, March 14, 2008.

[23] Fred Zwick, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, June 29, 2007.

[24] Otto Berndt, autobiography.

[25] Altona Branch general minutes, 93–96, CHL LR 10603 11. From Brother Witt’s apartment in Wilhelmsburg to Altona (approximately six miles as the crow flies), Brother Witt’s route on that occasion was certainly not direct.

[26] Otto Albert Berndt, “The Life and Times of Otto Albert Berndt” (unpublished autobiography), private collection.