Göppingen Branch

Roger P.Minert, “Goppingen Branch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 426–431.

Göppingen Branch, Stuttgart District

The city of Göppingen is located twenty miles east of Stuttgart on the main railway line to Munich. With 28,101 inhabitants in 1939, the city was in many respects representative of towns in the historic south German region of Swabia. [1]

| Göppingen Branch [2] | 1939 |

| Elders | 2 |

| Priests | 0 |

| Teachers | 0 |

| Deacons | 0 |

| Other Adult Males | 4 |

| Adult Females | 14 |

| Male Children | 3 |

| Female Children | 2 |

| Total | 25 |

The branch of the Latter-day Saints that met in rented rooms on the second floor of the building at Poststrasse 15 in Göppingen was one of the smallest in the West German Mission in 1939. Of the twenty-five members, only two (both elders) held the priesthood. The largest component of the membership were women over twelve years of age. The meeting schedule showed Sunday School beginning at 10:00 and sacrament meeting at 7:00 p.m. The Primary organization met on Wednesdays at 3:00 p.m. and the MIA on Wednesdays at 8:00 p.m.

The leader of this small branch throughout the war was Georg Schaaf. The other elder and the only other man listed among the branch leaders in July 1939 was Friedrich Weixler, who served at the time as the first counselor in the branch and as the superintendant of the Sunday School. The lone woman in the branch directory was Dorothea Weixler (the president of the Relief Society). [3]

Brother Schaaf kept detailed minutes of the meetings held in this small branch. Those minutes survived the war and give important insights into the status of the branch during the years 1939 to 1945. For the most part, only the activities of the meetings are given, with rare information about events elsewhere. For example, there is no mention of the departure of the American missionaries in August 1939 nor the outbreak of war a week later. Nothing is written about air raids over Göppingen or of the end of the war when the American army entered the town on Hitler’s birthday, April 20, 1945. [4]

Ruth Schaaf (born 1930), a daughter of the branch president, recalled that there were two rooms used by the branch at Poststrasse 15. She did not recall specific furnishing or decorations but said that there was a pump organ that was moved to her family’s apartment when the branch rooms were confiscated. “Some members from Ulm also came to our branch meetings because they didn’t have a branch anywhere near them.” [5] Werner Weixler (born 1932) recalled that Poststrasse 15 was an office or manufacturing building owned by the Stern family, who were Jewish. There was no sign on the building indicating the presence of the branch there. [6]

Friedrich Weixler (born 1909) was drafted into the German army in 1940. He had been employed as a department head in a leather factory but had attracted negative attention in at least one respect. One day the government suddenly discontinued paying child support to the Weixler family. When Brother Weixler inquired of the local Nazi Party boss, he was told that as long as he paid 10 percent of his income to the Church, he would not receive subsidies for his children. [7] “After my husband left for the service, we had just enough money to pay the rent but hardly any money for food or anything else,” recalled Dorothea Weixler (born 1910).

Like most German schoolchildren, Ruth Schaaf was a member of the Jungvolk. She recalled the experience in these words:

We mostly learned about the country’s leaders, for example, where they were born, etc. I still remember when Hitler was born and where. We also learned how to do crafts. We also wore our uniforms (that was required)—a white blouse and a black skirt combined with a khaki jacket. Later on, we also had a black necktie and a special kind of knot in the front. We went and waved whenever there was a parade. We also stood at attention at a specific location whenever there was a radio broadcast with a speech by the Führer.

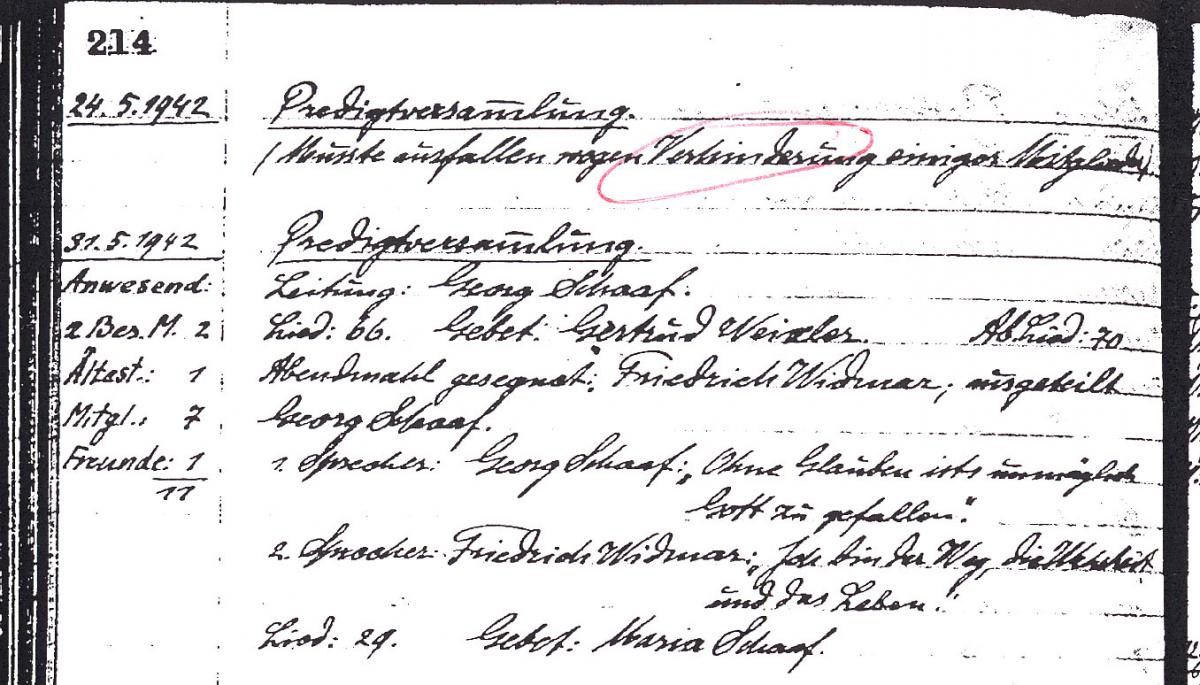

Fig. 1. An example ofGöppingenbranch minutes. (CHL)

Fig. 1. An example ofGöppingenbranch minutes. (CHL)

The branch minutes feature prominently the names of three families: Schaaf, Weixler, and Ceol. These families clearly constituted the majority of the attendees at sacrament and fast meetings for at least the years 1939 through 1942. The average attendance in those days was twelve persons (very precisely counted). An example of a typical sacrament meeting record is as follows:

May 31, 1942: Sacrament meeting

Presiding: Georg Schaaf; hymn 66; invocation: Gertrud Weixler; sacrament hymn 70; sacrament blessed by Friedrich Widmar and passed by Georg Schaaf. First speaker: Georg Schaaf “Without faith it is impossible to please God;” second speaker: Friedrich Widmar “I am the way, the truth and the life;” hymn 29; benediction: Maria Schaaf. Attendance: two members from the district, one elder, seven members, one friend. [8]

The average attendance at meetings of the Göppingen Branch actually increased during the war thanks to an influx of visitors from the district and other branches. From twelve persons in 1942, the number rose to seventeen in 1943 and eighteen during the final year and a half of the war. On occasion, there were as many as twenty-three persons present, but there were likewise days when only nine persons came to church. On a regular basis, district president Erwin Ruf inspected the records and added his signature of approval.

As the president of the Relief Society in Göppingen, Dorothea Weixler once arranged to have a celebration in the banquet room of a local restaurant, as she recalled: “But when we got there, we were not alone. Somebody from the government came to see what we were doing. We had a good party—and he liked it too. He stayed with us the entire time.”

Werner Weixler recalled the influence of the Nazi Party in his school. On political holidays, his teachers wore SA uniforms. He described some of his teachers:

I clearly remember two of them. I was still friendly with one of them after the war; he was just misled. But the other one was a real fanatic: Herr Beck. He was our history teacher and he always brought the Bible with him. He really knew the Bible, but not because he was a good Christian—just the opposite. He loved to show us everything bad about the Jewish people and their literature.

Magdalena Ceol (born 1931) was the daughter of an Italian (Guiseppe Francisco Ceol) and a German (Renate Marie Maier). The Ceol family regularly attended branch meetings (where Brother Ceol’s name was recorded as “Georg Franz”), but Magdalena recalled that social and political pressures were applied to her father because of his Italian heritage: “My whole family hated the German government because of this.” In response, Brother Ceol decided to take his family to Italy in 1943. They lived in relative peace there, although two of the Ceol sons were drafted into the Italian army. [9]

Heinz Weixler turned ten in 1943 and was automatically inducted into the Jungvolk program. He gave the following description of the group’s activities:

For me, it was a lot of fun. Every Wednesday and Saturday, we had to appear at the meetings. On Wednesdays, we put on our uniforms. We had one for the summer and one for the winter. Our leaders were only two or three years older than we were. The oldest boy in the entire unit could have been eighteen or nineteen. We even had our own rooms to meet in. They taught us how the war was going and we played war games. We went to the forest and had little colored strings around our arms. Red meant that that you belonged to one group, and blue the other group. They encouraged fighting and wrestling. It was a lot of fun for most of us but not for everybody. It depended on whether you were athletically inclined or not. But if there was a boy that was not physically fit, he was made fun of.

District conferences held in Stuttgart were evidently important occasions for the Göppingen Saints who could make the trip in less than one hour by train. The branch minutes indicate that substantial numbers traveled to the capital city twice each year to participate. On October 18, 1943, sixteen members and five friends from Göppingen attended the conference and were informed that the Stuttgart Branch rooms had been damaged so severely in an air raid on October 7–8 that they could no longer be used. [10]

A close study of the branch minutes allows the inference that President Georg Schaaf was in poor health for much of the war. At least once a month, meetings were cancelled due to his illness or simply the fact that he was unable to attend. On occasion, a visiting elder presided over the meetings. By mid-1944, Gottlob Rügner, an elder from the Feuerbach Branch, had been asked to assist the branch in Göppingen.

A sad development was recorded in the minutes in August 1944: “On August 9, we were required to make our meeting rooms available for use by people bombed out of their homes. Until further notice, the meetings will take place in the branch president’s apartment. The following items were left in the rooms: a stove, a table, two chairs, a lamp, and the blackout curtains.” [11]

Ruth Schaaf recalled that her family lived in a very poor neighborhood. Her father had suffered a serious injury to his hand as a young man, which prevented him from becoming a craftsman. This impediment relegated the family to a low socioeconomic status. Werner Weixler recalled being a bit embarrassed at entering the Schaafs’ neighborhood to attend branch meetings in the branch president’s home: “It wasn’t a great neighborhood, and I was embarrassed that when we were singing, the neighbors could hear us.”

Werner recalled another situation at school. He was an excellent pupil and was tested for candidacy for an elite Nazi Party school in Rottweil. It was a great honor in Germany at the time, but Friedrich Weixler would not sign the admission papers for his son. As a social democrat before the war, Brother Weixler was still very much opposed to Hitler’s party and the government. [12] Werner recalled being somewhat disappointed when one of the other boys chosen for that school came home on vacation: “I was jealous of him because he always had a sharp uniform. I could have been one of them.”

“I never met another Mormon soldier while I was away from home,” recalled Friedrich Weixler, “but I carried a Book of Mormon with me. I served in Russia, Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Albania, and France.” Back in Göppingen, Sister Weixler firmly believed that her husband would come home some day: “I never thought anything else,” she said. He came home on leave only two or three times during his five years of service and never wrote to say that he would be coming home soon.

By August 1944, Renate Ceol had returned from Italy to Göppingen with her daughter Magdalena, and the two experienced the air raids of the last few months of the war. During one of those attacks, the Ceols’ apartment building was hit by incendiary bombs. Magdalena recalled that when she and her mother emerged from the basement shelter as the all-clear signal sounded, the upper floors of the building were already on fire.

In 1944, Ruth Schaaf was called upon to serve her Pflichtjahr, an experience that she described as follows:

I served my duty year in the home of another family. I was allowed to choose between helping on a farm or living with a family who had many children. I helped a Mrs. Wendling, who had four little children. They also lived in Göppingen. At first, I still lived with my parents, but after a while I had to move in with the family. After I was done with my duty year [in February 1945], I worked for a wood company in Göppingen-Holzheim.

During one of the attacks on Göppingen, the Schaafs’ apartment house was damaged. Ruth recalled, “I was on my way down to the basement when I stopped and wondered where my little sister Elfriede was. I turned around, went back up to the apartment and found her underneath all the shattered glass from the window. I grabbed her and carried her downstairs.”

Elfriede Schaaf was only four years old when Göppingen was targeted by the Americans for bombings, but she clearly recalled being showered by glass that day. She explained that her parents usually took the children to a concrete bunker not far from their home but that they also took shelter in their own basement on occasion. “If I close my eyes the film starts: I can still see the bombs falling and my sister running out of the room. . . . I was only a child, but I already knew what war was about.” [13]

On the other hand, war had its elements of adventure for little boys. Werner Weixler recalled looking out the attic window to see the American bombers going by. On one such occasion, however, the thrill of the spectacle nearly turned to tragedy: “They were almost right overhead. Suddenly we saw the bomb bays open and the bombs dropping. We were so shocked that we had barely crossed the room when the first bombs struck the ground just a little ways down the street. [Afterward] we went out and saw huge holes in the street and houses burning.” One day, Werner went to school to find out that his closest friend was not there; he had been killed in an air raid.

With the events of the war intensifying in the spring of 1945, meetings of the Göppingen Branch were frequently canceled. Such was the case on four consecutive Sundays beginning on March 18. The entry on April 15 includes two important and rare events in the branch: infant Siegfried Schaaf was blessed, and Magdalena Ceol was confirmed a member of the Church. Both ordinances were performed by visiting elder Meinrad Greiner during the Sunday School hour “for fear of an impending air raid alarm.” [14] Just five days later, the American army arrived; the war was over for the people of Göppingen.

Little Elfriede Schaaf remembered interacting with the conquerors:

American soldiers were very good to us children. They shared their food with us. We each picked one soldier and called him my soldier. One time, while I was waiting for my soldier to come, I was trying to follow my siblings and friends when they climbed up onto something. But it was too high for me. A black soldier lifted me up and gave me a kiss on the cheek. I ran home that day thinking that I would turn black if I didn’t wash my face. So I washed. I told my mother the story because she was already wondering why I was in such a panic. She laughed when she heard what had happened.

“When the Americans entered Göppingen, we were hiding in the basement. We heard the trucks and tanks driving by,” recalled Heinz Weixler. “I was not scared when the Americans came to Göppingen,” his mother explained, “but I had a funny feeling. It was so strange to see the enemy in our town.” Like millions of Germans, they realized that they had lost the war and simply hoped for decent treatment at the hands of the victors.

Looking back on her youth during the war years, Ruth Schaaf offered this observation: “Even though it was a war situation, I was not afraid of getting hurt or dying. When the war was over, I was fifteen years old. So in a sense, playtime for me was already over anyway. But we found ways to entertain ourselves even despite the realization that there was a war being fought around us.”

Friedrich Weixler served as a communications specialist, his principal duty being to lay telephone wires. Looking back on his time as a soldier, he explained: “I was a good Mormon. I did not smoke or drink alcohol. I was a good soldier and did not shoot people. It was important for me to not be guilty of that. The Lord protected me in every way.” On one occasion, Friedrich was commanded to execute four civilians but was fortunate because even though he declined to shoot innocent civilians, he escaped punishment for refusing to obey an order. In May 1945, he was captured by the Americans in southern Germany. However, in the confusion of the immediate aftermath of the war, he managed to slip away and make his way home to Göppingen. He thus avoided what could have been years of imprisonment.

The city of Göppingen suffered four major air raids that cost at least 325 people their lives, and approximately two thousand of the town’s men had died for their country. [15] On May 6, 1945, Georg Schaaf made his first peacetime entry in the branch minutes, allowing the presumption that the Göppingen Latter-day Saints were determined to maintain the life of their branch in a ruined but renewed Germany. They had weathered a terrible war and remained faithful in their callings.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Göppingen Branch did not survive World War II:

Erich Arthur Ceol b. Göppingen, Württemberg, 22 Apr 1919; son of Joseph Franz Ceol and Maria Renata Maier; bp. 10 Oct 1929; conf. 10 Oct 1929; missing as of 20 Mar 1944 (CHL CR 375 8 2445, no. 783; FHL microfilm no. 25738; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI; AF; PRF)

Wilhelm Rube b. Unterurbach, Jagstkreis, Württemberg, 25 Nov 1878; son of Johann Georg Rube and Sabine Zehnter or Zehender; bp. 13 Sep 1929; conf. 13 Sep 1929; m. 28 May 1910, Margarethe Katherina Stettner; 2 children; d. suicide, Göppingen, Donaukreis, Württemberg, 29 Jun 1946 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 399; FHL microfilm no. 271407; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Paulina Wittlinger b. Holzheim, Donaukreis, Württemberg, 6 Sep 1871; dau. of Johannes Wittlinger and Katharine Hörmann or Hermann; bp. 14 Jul 1929; conf. 14 Jul 1929; m. —— Lang; d. old age 7 Nov 1946 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 381; FHL microfilm no. 271383; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI; PRF)

Notes

[1] Göppingen city archive.

[2] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CR 4 12.

[3] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[4] Göppingen Branch general minutes, vol. 15, CHL LR 3235 11.

[5] Ruth Schaaf Baur, telephone interview with the author in German, April 13, 2009; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski. The city of Ulm was thirty miles southwest of Göppingen.

[6] Werner Weixler, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, March 23, 2007.

[7] Friedrich, Dorothea Gertrud, and Heinz Weixler, interview by the author in German, Salt Lake City, March 16, 2007.

[8] Göppingen Branch general minutes, 214.

[9] Magdalena Ceol, telephone interview with the author in German, April 28, 2009.

[10] Göppingen Branch general minutes, 226.

[11] Ibid., 235.

[12] Friedrich Weixler was one of many Germans who listened to BBC radio broadcasts, which was strictly illegal. Werner recalled how his mother scolded her husband for endangering himself and the family.

[13] Elfriede Schaaf, telephone interview with the author in German, April 13, 2009.

[14] Göppingen Branch general minutes, 240. Magdalena told of being baptized in an indoor pool in Stuttgart.

[15] Göppingen city archive.