Frankfurt Branch

Roger P. Minert, “ Frankfurt Branch, Frankfurt District,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 91–113.

For centuries, the city of Frankfurt am Main in southwestern Germany has played an imortant role in commerce and transportation among the German states. It was also the center of politics in the Holy Roman Empire; dozens of emperors were crowned in the cathedral there (though they ruled elsewhere). As World War II approached, this city of 548,220 was the home of the nation’s largest railroad station and the largest airport and was the point of departure for the first completed stretch of the new autobahn highway system. [1]

The Frankfurt Branch met in the summer of 1939 in rented rooms at Neue Mainzerstrasse 8–10, just a few blocks north of the Main River and very close to the office of the West German Mission at Schaumainkai 41 (on the south side of the river). Among the 261 members of the branch were nineteen elders—a wealth of leadership when compared to other branches in the mission in those days. As was true in most Church units, more than half of the members were females over the age of twelve.

Since its inception in 1894, the branch in Frankfurt had moved time and again in an attempt to find suitable rooms in which to meet and worship. The history of the branch indicates that the rooms at Neue Mainzerstrasse 8–10 were in a Hinterhaus by a photography store. Erna Huck (born 1911) recalled that the meeting rooms were on the second floor and that there were several classrooms for children and teenagers. [2] Photographs of the rooms show a picture of Jesus Christ flanked by pictures of the prophets Joseph Smith and Brigham Young. The branch sang hymns accompanied by a pump organ. Several eyewitnesses recalled a modest sign on the street indicating the presence of the branch at that address.

Maria Schlimm (born 1923) recalled the following about the building at Neue Mainzerstrasse 8–10 and the schedule of the meetings:

It was a large building with many offices. [We rented] a large room and four smaller rooms for other classes. Upon entering the main door, you could see the wardrobe and some benches where we waited until the meeting started. There was a large painting in the [chapel] showing Christ and Joseph Smith in the first vision. The member who painted it worked in an art museum. . . . There was a rostrum at one end of the chapel; it was not large enough for the choir but we used it for theatrical plays on special occasions. [3]

| Frankfurt Branch [4] | 1939 |

| Elders | 19 |

| Priests | 4 |

| Teachers | 4 |

| Deacons | 16 |

| Other Adult Males | 39 |

| Adult Females | 160 |

| Male Children | 11 |

| Female Children | 8 |

| Total | 261 |

“Those were very nice rooms, and they reminded me of an office,” recalled Hannelore Heck (born 1929). Her description continues:

The rooms were a fairly good size, and it was nice for us to have Sunday School and sacrament meeting in different places. I think it was more of an office than an apartment building. We used the building often, holding MIA on Wednesday nights, Relief Society on the first Sunday of the month, genealogy class on the second Sunday, and Primary on Tuesdays at 2 p.m. We walked to church so many times during the week. [5]

According to young Hermann Walker (born 1929), “We had a lot of fun in that building because it had two entrances. One was just the regular entrance upstairs. We had to walk through several classrooms and then enter what we called the chapel. We also had a stage up in the front and behind that stage was another door that led to the stairs again. We used this door for socials and whenever we performed plays. . . . None of the rooms we met in [at various addresses] looked like chapels we use today.” [6]

Carola Walker (born 1922) recalled that perhaps one hundred persons attended church meetings on a typical Sunday. [7] Her parents, Friedrich and Martha Walker, had a little apartment on the outskirts of the city, so it was not easy for them to attend church. Otto Förster (born 1920) recalled an attendance of perhaps fifty to sixty people. His family walked to church from Koblenzerstrasse, about thirty minutes away. According to Otto, “The Church had use of the rooms all week long. We didn’t have to share the rooms with anyone.” [8]

A native of Gotha in Thuringia, Karl Heimburg (born 1924) moved with his family to Frankfurt in 1938. Moving from a small branch in a small city to a very large branch in one of Germany’s largest cities, Karl noticed a distinct difference: “When we came to Frankfurt, there was a big branch; it was a totally different church with a complete Church organization. There was sacrament meeting, Sunday School, priesthood meeting, Relief Society, MIA, Primary—everything. It was like a big family.” [9]

At the age of fourteen, Maria Schlimm joined the League of German Girls. “I always liked it because nothing bad happened there. We did handwork, crafts, gymnastics, and choir. But there was nothing political attached to it. Whenever Hitler came to town, we had to wear our uniforms and stand by the side of the street so that he could see us.”

Annaliese Heck (born 1925) had a very different experience in the Hitler Youth program: “I had resisted the program a lot because they also met on Sundays some times.” Fortunately for her, she was invited to join an orchestra because she played the violin and the viola. “At least we didn’t have to march around.” [10]

When the West German Mission conference was held in 1939, the members of the Frankfurt Branch were called upon to help set up the meeting venues. As was the custom for mission and district conferences all over Germany in those days, members of the local branch also took into their apartments members who were close friends or had traveled from far away and lacked the funds to stay in hotels. On the Monday following the last conference sessions on Sunday, several hundred Saints joined together for a cruise down the Rhine River. [11]

Otto Förster had spent two and a half years in the Hitler Youth but discontinued his involvement when he became an apprentice electrician working in Königstein (about ten miles west of Frankfurt). His work with the Siemens Company was critical to the war effort, so he could not be drafted by the Wehrmacht early in the war. This protected status allowed him to remain at home, attend church, and pursue a relationship with a young lady in the mission office—Ilse Brünger of the Herford Branch in the Ruhr District.

Just before the war, newlyweds Hermann and Erna Huck purchased a small grocery store at Rotlinstrasse 53 and operated it under the name Lebensmittel Huck. Their customers were the residents of the apartment buildings within a few blocks and included several Jewish families. The store featured such expected products as coffee and wine, but when asked about the quality of such products, the Hucks had to admit that they had no idea how such items tasted. The customers knew that the shop’s owners did not drink coffee or alcohol.

As the persecution of the Jews intensified, the Hucks came under pressure from certain neighbors to stop allowing Jews in their store. One woman made it a point to greet the Hucks with a hearty “Heil Hitler!” each time she entered the store, and it was likely that woman who applied the greatest pressure. However, Hermann Huck was not to be intimidated, and he continued to sell to Jews. To avoid endangering both himself and his customers, he met them after hours and provided them whatever he could. This was a difficult undertaking, because he was only allowed to sell items in exchange for ration coupons, and Jews had a very hard time obtaining ration coupons from city authorities.

After the American missionaries departed Germany on August 25, 1939, the only full-time missionaries still in service were in the mission office at Schaumainkai 41. [12] That preparations for war were underway among the populace is clear from a letter written by secretary Ilse Brünger to President M. Douglas Wood on August 28 (just after he arrived in Copenhagen, Denmark, with his evacuated missionaries): Sister Brünger had given the Frankfurt Branch 47.60 Marks to pay for blackout paper to cover the windows of the meeting rooms as required under civil defense laws. [13]

Hans Mussler (born 1934) lived in the spa city of Baden-Baden when the war began. With his mother, Frieda, and his sister, Ursula, Hans first attended church in the Bühl Branch a few miles distant. When his father, Franz Schmitt, was offered a choice for his next assignment, he selected Frankfurt over a small town near Lake Constance. According to daughter Ursula (born 1929), Herr Schmitt wanted to assure little Hans a “proper education.” [14] Hans became not only a member of one of the largest LDS branches in all of Germany but also a member of another important institution—the Musisches Gymnasium. Admission was only via recital, and competition was stiff. According to Hans, there were two such state-run schools—one for boys in the Frankfurt suburb of Niederrad and another for girls in the city of Leipzig. [15] Both schools were exclusive, and the pupils were required to live in the buildings.

After the fall of France in the summer of 1940, Otto Förster was sent by his employer to Dunkirk, where the Germans were repairing harbor facilities damaged by the retreating British and French. As he recalled:

They had blown out the hinges of the two main gates of a lock. When I got there the gates were just hanging in the water. The first gates were operated by hydrometrical motors. So they sent me out there to check out the controls. I was part of a construction unit. When the British left, they also just dumped all they had left (such as vehicles) into the locks. That gave them a little more time. We used cranes to get them out, and it took us about a week. I was there for twelve to fourteen days. Then I went home and found an order to report to the military. I had gone to Dunkirk as a civilian because it was a work assignment.

Otto’s first assignment with the air force was in Thuringia, where he was to be trained for work with antiaircraft guns. However, a call went out for drivers, and he already had a driver’s license (a rare possession in those days; his premonition a few years earlier that he might need one someday paid off). “While others had to practice shooting cannon, I was driving around Thuringia sightseeing, which was much easier.”

Hermann Huck was the son of Anton Huck, then the president of the Frankfurt District and later the supervisor of the entire mission. As typical store owners, the young Huck family lived in rooms just behind their business that fronted the street on the ground level of the building. They enjoyed their lifestyle, but it did not last long. By September 1940, Hermann was drafted into the Wehrmacht, and they had to close down their store. Erna was allowed to stay in the building but lost the kitchen and had to make do with one bedroom in the apartment, where her son was born later that year.

The first tragic loss of life among the Latter-day Saints in Germany and Austria during World War II involved the Frankfurt Branch. Corporal Willy Klappert (born 1914), a deacon in the Aaronic Priesthood, was killed on September 2, 1939—the second day of the war—in the town of Jegiorcive, Poland. He was therefore the first of hundreds of LDS men to lose their lives while wearing the uniform of the German armed forces. By the time the war was finally over and German POWs were released from camps all over the world, several other members of the Frankfurt Branch had perished.

The minutes of meetings held by the Frankfurt Branch during the years 1939–45 give valuable insights into the life of the branch and its members. In those minutes we read that Ludwig Hofmann assumed the role of branch president when the missionaries left town. The average attendance in Sunday meetings in 1940 was fifty-five members and friends. The clerk indicated that the winter of 1939–40 was long and hard and that the members endured shortages in coal supplies. [16]

According to the branch records, a “severe air raid” over Frankfurt on July 8, 1941, resulted in “great damage” within the city. There is no mention of damage to the meeting rooms at Neue Mainzerstrasse 8–10. However, on March 8, 1942, the meetings had to be cancelled because there was no heat in the rooms. For the year 1942, the average attendance had decreased to forty. On August 2 of that same year, branch president Ludwig Hofmann died; he was buried in the Rödelheim Cemetery in northwest Frankfurt in a ceremony over which district leaders presided. New branch leaders were called on August 16, 1942: Hermann Ruf (a native of Stuttgart) was the president, Hans Förster was the first counselor, and Valentin Schlimm was the second counselor. [17]

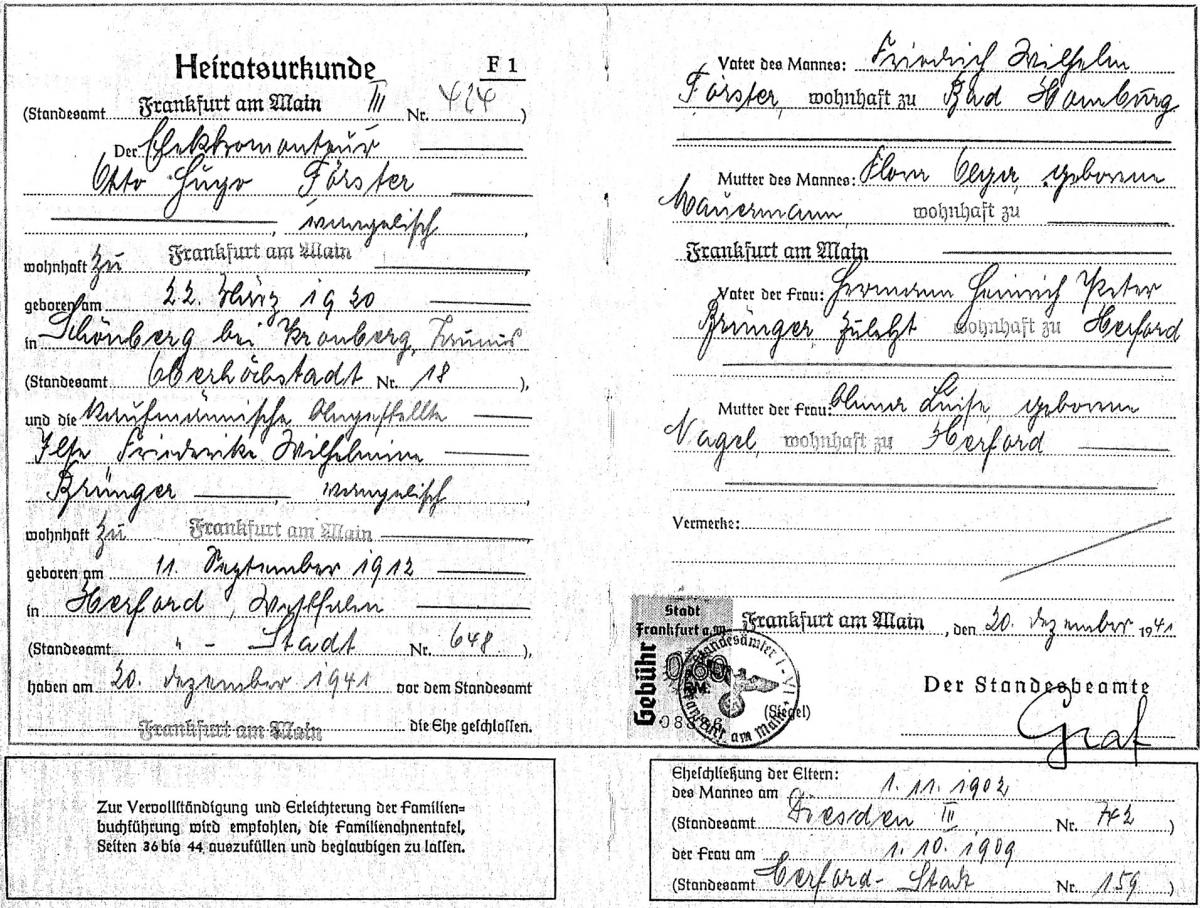

In 1941, Otto Förster was again in France. Due to long hours of stressful driving and poor nutrition, he became seriously ill and spent several months in field hospitals before being sent to a hospital in Brussels, Belgium. Eventually, his condition was considered sufficiently serious to merit him a release from active duty. For the rest of the war, he was classified as “fit for domestic [non-combat] duty only.” He recognized this right away as a great blessing. His next assignment was to a post at Wreschen in Posen. During his year at that location, he received permission to marry Ilse Brünger, who was responsible for financial records in the mission office at Schaumainkai 41. His leave allowed him only one week at home, but the wedding on December 20, 1941, was a fine event that took place in Frankfurt’s family city hall and in the branch meeting hall.

Fig. 1. Marriage record of Otto Förster and Ilse Brünger on December 20, 1941 (O. Förster).

Fig. 1. Marriage record of Otto Förster and Ilse Brünger on December 20, 1941 (O. Förster).

Ilse Brünger was eight years older than Otto and later wrote of her feelings during the courtship: “I liked him too, but since he was younger, I was not too serious at first. I prayed about him and then I felt that God approved of him. . . . Then he was drafted. Only those who went though the same agony of not hearing, not knowing where he was, if he was still alive or not, can understand the fear and terrible thing war brought to nearly every family.” Ilse had many friends in the branch, which was especially because her family was very close to disowning her due to her membership in the Church. [18]

By November 29, 1942, the branch meetings had been moved up the street to rooms at Neue Mainzerstrasse 68; a district conference held at that location featured a full-house contingent of members from the six branches. [19] This address apparently remained unchanged until January 1944.

“I remember vividly that our parents always made sure that we knew that whatever we talked about at home should not leave home,” recalled Hannelore Heck. “Our beliefs were our beliefs, and my father didn’t think it was wise that the Nazi Party would find out about those. From the time I was very small, I realized that the less I said, the better off I was. We knew that they would take our daddy away from us if we said anything and that he would get killed.” At the age of ten, Hannelore was inducted into the Jungvolk with her classmates, but she did not like the activities, which she described as “boring and stupid.” It appears that her particular group was disorganized because nobody came to the Heck home to learn why Hannelore missed so many meetings.

Cooler heads prevailed in Hannelore’s school. She recalled:

I had wonderful teachers—especially my history teacher. She would put up a huge map of the world, and Germany would be marked with a distinct color. But what we learned from that was not how special Germany was but how small it really was compared to the world. She never said a word but only hung up the map at the beginning of class and then again at the end. We didn’t have to be told what she was thinking—we knew it. Her message was that some insane man was trying to fight the entire world.

Fig. 2. The main meeting room of the Frankfurt Branch in 1939. Future mission supervisor Christian Heck is seated front right. (E. Wagner Huck)

Fig. 2. The main meeting room of the Frankfurt Branch in 1939. Future mission supervisor Christian Heck is seated front right. (E. Wagner Huck)

Erna Huck enjoyed her life as a stay-at-home mother in Frankfurt until the air raids over the city became more severe and frequent. With the public air-raid shelters too far away to be convenient, the Hucks joined their neighbors in the basement of their apartment house when the sirens began to wail. She recalled:

There was only one small room about twelve by fifteen feet in size, and there were fourteen of us. It felt like we were in a mousetrap. My little boy was the only child in the group. Usually the raids came late at night when it was totally dark [under blackout conditions], but later they also attacked in broad daylight. Sometimes we went downstairs two or three times in a single night. We always took our important papers along—our marriages certificate, photographs, financial papers, etc.

Johann Walter Uhrhahn had served as a full-time missionary in Germany in the 1930s. After returning to Frankfurt, he married Lola Haug, and they had two children—Wolfgang (born 1936) and Vera (born 1941). By the time Vera was born, Walter was well established in a large construction firm that was nationalized just after the war began. Brother Uhrhahn soon found himself traveling to many locations all over eastern Europe, recalled where his company carried out contracts for road and bridge construction. Wolfgang recalled, “My mother told me later that I had been in thirteen countries including Poland, Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Greece. My father worked with payroll matters and also functioned as the liaison between the company and the local government. He was never in the military but often wore a uniform because he was representing the German government.” [20] As conquerors, German civilians and paramilitary operatives were usually treated poorly by the occupied peoples, but Wolfgang recalled vividly that “people in countries like Romania, Bulgaria, and Ukraine welcomed us with open arms.”

The Uhrhahn family rented an apartment on the main floor of a building at Waldschmidtstrasse, a few blocks east of the center of town, but the family was usually far from home. Luise Uhrhahn was determined to travel with her husband in order to spend as much time with him as possible, and because of his civilian status the government did not object. Wolfgang and Vera received their schooling at home, wherever home happened to be. Brother Uhrhahn was so successful in employment that the family often stayed in expensive hotels in large cities. This was not typical of a German family at the time, nor was it common for Germans to have several weeks of vacation each year, as the Uhrhahns did. It became their habit to spend vacations in alpine winter sports locations.

Karl Walker (born 1935) had vivid memories of the radio in his home during the war: “My mother listened to BBC quite a bit although it was forbidden. One time, I was home alone and turned it on. I remember how angry she was when she found out, and I never did it again. She also stopped listening to it—maybe because she was afraid that I would talk to somebody about it outside the home.” Regarding the incessant national broadcasts, Karl recalled, “The radio always aired special reports of victories everywhere. People got more and more excited about the whole thing. The reports were called Sondermeldungen (special announcements), and they always started with [military] music. I also remember hearing Hitler talk on the radio. He always pronounced the word Soldat (soldier) very distinctly. The sentence was always “Wir kämpfen bis zum letzten Soldat! (We’ll fight to the last soldier!).” [21]

After doing an apprenticeship as a mechanic, Karl Heimburg was drafted into the Wehrmacht on October 10, 1942, and assigned to a motorized unit:

We were classified as forward reconnaissance; in other words, we had to move ahead of the tanks quickly. We were kind of like the gypsies, we would escort convoys someplace because they didn’t know the way. We would protect them from surprise attacks; we would open up the ways for the tanks to break out [if they were surrounded]. When the tanks broke through, we pulled out and went elsewhere. We were in the middle of a mess all the time.

By January 1943, Karl was on the Eastern Front. It was the aftermath of the crushing defeat of the German Sixth Army at Stalingrad, but Hitler was determined that his army was not to retreat from the interior of the Soviet Union. Karl was part of several offensive and many defensive campaigns all year long. Beginning in May, he was trained as a driver for the Mark IV tank. “It weighed twenty-eight tons and was a good tank,” he explained. The action on the Eastern Front that year was so frequent and so intense that “our days were thirty-six hours long, not twenty-four, and that was that.”

Fig. 3. Priesthood brethren of the Frankfurt branch. (E. Wagner Huck)

Fig. 3. Priesthood brethren of the Frankfurt branch. (E. Wagner Huck)

Karl was wounded on several occasions. Once he had seven pieces of shrapnel removed from his leg. On another occasion a bullet penetrated his side but did so little damage that he did not notice it during the heat of battle. Once a bullet pierced his right hand. Fearing that he would lose touch with his comrades, he refused to be sent to a hospital. However, a serious infection set in, and he was compelled to go to the hospital after all. Later there was no problem in rejoining his unit.

Everywhere he was stationed while away from home, Karl Heimburg was the only LDS soldier around. He found that most German soldiers had no interest in discussing religion. “It was always a neutral thing. Sometimes a Lutheran pastor presided over the service, sometimes a Catholic priest.” On the matter of prayer, he stated,

You said your prayers whether you wanted to or not. Sometimes they were very short. It was not only me but almost everybody [who prayed]. There were times when you saw people actually sitting down in prayer. You knew they were praying. And sometimes they’d be in the middle of a battle; in fact, in the middle of a mess it was actually easier to pray. To me it was the only thing we could get help from. At the moment, it was all you really needed.

While in the Soviet Union, Karl noticed the devout faith of the older generation. “I didn’t see a single home that didn’t have a prayer altar. There was always a little candle burning and a picture of Jesus and his mother. You could tell that the [older] people still had faith.”

Karl’s belief in the Word of Wisdom came in quite handy when he sold his tobacco and alcohol rations to other soldiers. “I never saw a [German soldier] who didn’t drink and smoke,” he recalled.

After a year of furious action, Karl Heimburg contracted malaria and yellow jaundice in November 1943. While he languished in a hospital in Vienna, Austria, for ten weeks, his weight dropped from 180 pounds to 98. When his mother arrived from Frankfurt to visit him, his comrades hurried to dress him in many layers of clothing in an attempt to hide his emaciated condition from his mother. “She never knew,” he recalled.

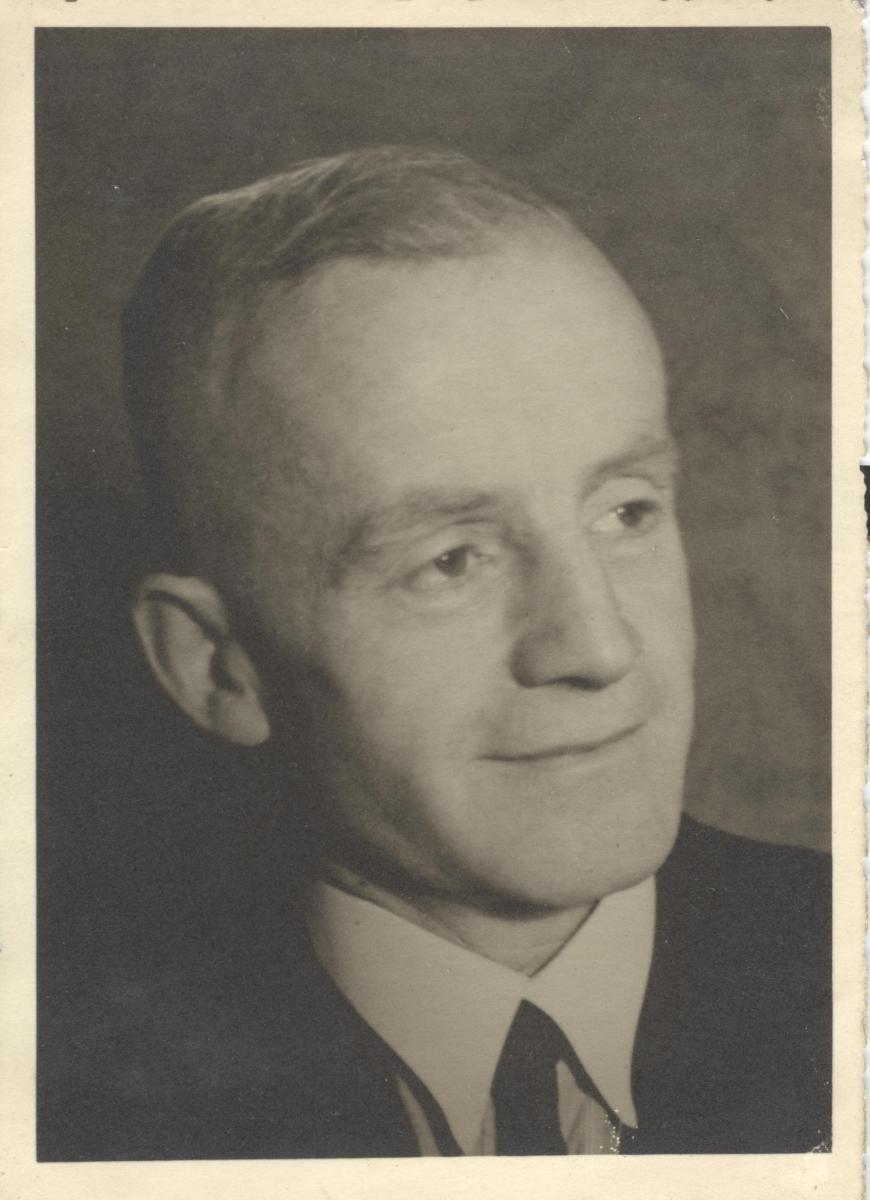

Fig. 4. Hermann Ruf was the president of the Frankfurt Branch for much of the war. (G. Ruf)

Fig. 4. Hermann Ruf was the president of the Frankfurt Branch for much of the war. (G. Ruf)

In January 1943, bombs struck Sister Huck’s neighborhood as she and her three-year-old son huddled with neighbors in the basement shelter underneath her apartment. The building across the street burned to the ground, as did the building behind theirs. For a while, it seemed as if they would not be able to exit the shelter that night, but they were able to crawl through an escape hole into the basement of the adjacent building and eventually made it out into the street. All of the windows in their building were broken, but the building survived. Nevertheless, Sister Huck decided to evacuate Frankfurt with her son. Along with her father, Friedrich Wagner, she took her son to the home of her aunt in the small town of Hirsau near Pforzheim, about one hundred miles south of Frankfurt. She was allowed to store her furniture in one room at her Frankfurt address.

Anneliese Heimburg recalled the precautions taken by city officials to protect residents from disaster in the case of air raids. Each apartment building was to have a barrel of water in the basement along with a supply of blankets. In the case of a fire in the building or the neighborhood, each person was to soak a blanket in the water and put it over his or her head before leaving the shelter. This tactic proved successful in the prevention of suffocation. In addition, a small hole was to be cut into the wall of each adjacent building to allow for additional escape routes. [22] Annaliese recollected that “the government carried out a big rat-extermination program before the war because they figured that if bombings started, there would be corpses and pestilence, and they wanted to prevent that.”

Home on leave from Braunschweig, Otto Förster returned just two days before the birth of his daughter, Ilse, on March 9, 1943. Because Otto’s wife, Ilse, was still an employee of the West German Mission and was living in the office building at the time, the baby was born in Ilse’s bedroom. The air raids over the city at the time were so dangerous that Sister Förster chose to take her baby home to her family in Herford, where the child stayed in relative safety until the end of the war. The mother returned to the mission office to continue her tireless service to mission leaders Christian Heck and Anton Huck. [23] Fortunately, she was allowed to quit her job in the military censorship office.

Otto Förster was next transferred to Steyer, Austria, where he supported antiaircraft crews defending automobile factories against American aircraft based in Italy. As he recalled, “I had to go to Linz to get supplies for our group. Whenever I was in Linz, [the enemy] bombed Steyer; and when I was in Steyer, they bombed Linz. The Lord was watching out for me.” [24]

In 1943, Elsa Heinle (born 1920) was working a second job as a streetcar conductor. She had been trained in tailoring, but her country needed her and other young women to take over the civilian jobs of men called into the military. Operating the streetcar under total blackout conditions was challenging. Because Elsa could not see the passengers, she called out to them to ask if anybody else wanted to get on or off. Then she rang a bell to signal the driver that he could start.

Elsa was still living with her parents, Karl and Lena Heinle, in 1943. When the air-raid sirens sounded, they each carried a small suitcase downstairs to join their neighbors in the basement shelter. As the war went on, they found it easier to simply go to bed with their clothes on rather than to get dressed and undressed several times within a few hours. In the basement they had just enough light to see, but Elsa recalled once knitting a little jacket for her friend’s baby. She clearly recalled a momentous air raid just before Christmas in 1943:

I was a streetcar conductor and rode line 16. On December 20, 1943, I worked the late shift until 1:00 a.m. . . . We arrived at the last station when the sirens went off, and it was a blessing that there was a shelter we could go into. [Afterwards] I walked around the corner to see if my house [at Neuer Wall 19] was still standing. All I saw was that it was destroyed. I knew that my parents were in the [public] shelter, but I still started screaming at the top of my lungs. Somebody came up to me and told me that my parents were still alive and that I should stop screaming. In that [basement] shelter, four people died. I was told that the bomb hit the basement and then lifted up the house, which then collapsed. [25]

After air raids, survivors often went around the neighborhood to see if anybody needed help. With this in mind, Elsa once went down the street to look for her friend’s mother. The woman’s body was found in the rubble underneath a huge cabinet. When Elsa told somebody that she had to write to her friend about the death of her mother, she was admonished by police to state that her friend’s mother had “died for Germany.”

From the branch records it appears that the new leaders felt the need to improve attitudes and behavior among the Saints there. On July 11, 1943 (eleven months after they were called to lead the branch), the presidency introduced these “new rules for the branch”:

1. Know that you are in a holy place where the word of God is spoken by His servants.

2. Loud laughter and inappropriate conversations have no place here.

3. There should be no talking at all in the chapel—before or after the meeting.

4. Find a seat in the front rows; pray in silence for divine inspiration that His servants will proclaim the word of the Lord.

5. If you are called upon to pray, then pray concisely and seriously without using many words.

6. In the testimony meeting, keep it short; do not rob your neighbor of his time.

7. In the discussion classes, keep your comments short and to the point; political statements are not allowed.

8. If you are talented, take part in the program and inspire the rest of us.

9. Be dignified when partaking of the sacrament and remember the Lord, our Savior.

10. After the benediction leave the room with gratitude in your heart. Other rooms may be used if conversations are absolutely necessary.

11. Be punctual for all worship services and leadership meetings.

12. Be sure that your name is on the roll for each class so that you will take part in the Kingdom of God.

13. Only priesthood holders are to handle the sacrament trays.

14. Value and support the priesthood holders because they have a weighty responsibility.

15. Only call upon the elders if you are seriously ill.

16. Do your very best to live a life pleasing to God and do your best to apply what you hear here in your daily life, then you will receive a crown of glory. [26]

The clerk noted that “the above principles were accepted by all attendees by the raising of the right hand.”

It would appear that the focus of the new rules was the improvement of worship services. The new branch leadership must have felt that reverence in the meetings needed to improve and that prayers, testimonies, and comments were becoming unnecessarily long. Item 7 suggests that members were making political statements, but no eyewitness accounts substantiate this; perhaps the guideline was made as a preventative measure. At the time, the average attendance in Sunday meetings was holding relatively steady at forty-five.

Being loyal to the Church and to the government at the same time was not an easy task for many Latter-day Saints, and there were discussions about politics within the walls of the church on occasion. Maria Schlimm recalled that in one such discussion, her mother expressed her opinion. Another member, who supported the government and the Nazi Party, remarked that if Sister Schlimm were not a member of the Church, he would have reported her to the authorities. On the other hand, Marie did not recall that the government caused the branch any problems at all.

Sometime in 1943, the Uhrhahn family lost their apartment to an air raid. Fortunately, the family was away from home at the time. Sister Uhrhahn’s father called her at their vacation apartment and informed her that all of their belongings had been lost. When Hans Walter Uhrhahn returned to work following their vacation, his wife took the children to her mother’s ancestral village of Hohenfeld in Bavaria. From there they continued to follow him to work sites in southeastern Europe. It was a nomadic gypsy lifestyle, but they preferred it to that of many of the families in the Frankfurt Branch, who were separated for months or even years at a time.

Hans Mussler’s music school was damaged in an air raid on Christmas in 1943, and he was allowed to leave town until the school could be called into session again. His mother and sister had left the city a few months earlier after their apartment was destroyed and were then living in Mühlacker near Pforzheim, two hours south of Frankfurt. Hans joined them there. In early 1944, the school reopened at a different location—the former convent at Untermarchtal, near Ulm in southern Germany. Hans was then isolated from both his family and his church, but he was enjoying his musical studies nonetheless.

By the end of the year 1943, air raids over Frankfurt were beginning to threaten the branch with increasing frequency. The clerk indicated in December that “the members were spared,” and on January 2, 1944, many expressed their gratitude to God for surviving “heavy raids” in recent attacks. [27] Conditions deteriorated just weeks later, as reflected in the minutes: “January 29, 1944: In one of the worst raids on Frankfurt, the branch rooms at Neue Mainzerstrasse 68 were burned to the ground. It happened on Saturday at 10 a.m. Due to the many raids, many members have moved out of town.” [28] There is no indication in the record just when the Saints began holding meetings at that address, but for the next while, they met in the mission home.

The clerk made the following sad entry in March 1944: “9/

March 24, 1944: Branch President Hermann Ruf was staying in the hotel Deutscher Hof and had left his briefcase with the branch records there. The terrible fire that began downtown at 8 p.m. on March 23 became a fire storm and [eventually] spread to that hotel. The next day at about 10 a.m. Brother Ruf ran into the hotel that was already burning and got to the second floor, where he was able to rescue from the flames the briefcase with the membership records. This was only possible with the help of the Lord. [29]

The year 1944 may have been a very long one for Hermann Ruf, because his fortunes vacillated from sorrow to happiness. In January or February, his family’s apartment was destroyed. On April 4, his wife, Frida, died of a kidney ailment after giving birth to a daughter on March 31. Frida was buried in Frankfurt on April 11 and her newborn daughter, Dorothea Gisela, died two days later. On December 20, President Ruf married Gertrud Glaser, whom he had met while attending meetings as a priesthood visitor in the nearby Bad Homburg Branch. Following the obligatory marriage ceremony in the city hall, mission supervisor Anton Huck presided over a modest church ceremony that was described by the branch clerk in these words: “Despite air-raid alarms that delayed the ceremony, it was a spiritual and uplifting occasion.” At the time of his wedding, Hermann Ruf was in uniform but at home between assignments. Valentin Schlimm had been designated temporary branch president on November 15. [30]

Following a recuperation furlough in Frankfurt, Karl Heimburg was shipped to his unit, which was temporarily stationed in Munich. From there it was back to the Eastern Front, which had since moved from Russia west into Poland. Karl arrived just in time to participate in an intense enemy counterattack that resulted in serious losses to the German side. It was August of 1944. “We had super, super equipment, but the [soldiers] didn’t know how to use it properly. They were all young kids. We had 120 recruits in our company who had never seen live guns fired. I wasn’t afraid of the Russians, but I was afraid for our own guys if the Russians ever attacked us.” The Red Army did attack—on January 17, 1945. Karl was separated from his unit for seven hours. Given a motorcycle and told to catch up with his unit, he headed in what he thought was the right direction, but he never saw his comrades again. “All of a sudden there were all of these people around me, a handful of whom spoke a foreign language. They said ‘Come on!’ and they liked me so much that they kept me for four years and seven months!” Karl joked. He became a Soviet POW, and life changed immediately in many ways.

A great number of German schoolchildren lost school time due to air raids. Finishing the eight years of public school was crucial for boys and girls, so the city government went to great lengths to replace damaged or destroyed schools. In the case of Hermann Walker, this meant sending his entire class to the village of Lollar, forty miles north of Frankfurt. As with so many children in Hitler’s Germany, Hermann was isolated from his family and his LDS friends for about a year. In his case, school attendance was particularly important, because he had developed talents in physics and chemistry and hoped to continue his education.

Fig. 5. This monument near Frankfurt’s city hall reminds pedestrians of the thousands of residents who were killed in air raids over the city and as soldiers at the front (R. Minert, 1979).

Fig. 5. This monument near Frankfurt’s city hall reminds pedestrians of the thousands of residents who were killed in air raids over the city and as soldiers at the front (R. Minert, 1979).

“My father had lots of inspiration,” recalled Annaliese Heck. Christian Heck had been the mission supervisor since the drafting of Friedrich Biehl by the Wehrmacht in 1940. In about 1943, he was offered employment by the government in occupied territories such as Czechoslovakia, possibly because he knew English and had also studied French and Italian. He apparently recognized this as a dangerous job, because several Nazi Party leaders and military officials had been killed by partisans in that area. He ultimately turned down the offer, then went home and told his wife that the party would get back at him by having him drafted. He was correct in his assumption and was in uniform in early 1943.

Before leaving for military service, Brother Heck decided to rent an apartment for his family in Kelkheim, about twelve miles west of Frankfurt and far from major industries and population centers. The family was able to move some items of great value (such as documents) to that location before their apartment was destroyed on March 18, 1944. By that time, his second daughter, Hannelore, had been moved with her school class to the town of Bensheim, about thirty-five miles south of Frankfurt.

Hannelore Heck recalled seeing bright skies over Frankfurt from Bensheim after major air raids. “The city was burning, and I knew that my family was in jeopardy.” After one terrible raid, she had to wait for an entire week before she learned that they were safe. On the other hand, she happened to be home the night their neighborhood was hit and their apartment destroyed. She recalled their escape from the burning building:

We threw wet blankets over our heads so that we wouldn’t get burned. We ran to the river [a few blocks south] to get some fresh air and to be near the water just in case we were in danger [i.e., if the flames came nearer]. . . . The entire downtown burned—it was not the first air raid on the city, but one of the first big ones. We lost all of our possessions except for what we carried in our suitcases. We had some clothing and some other valuable personal items like genealogical papers.

As was the case with other Wehrmacht soldiers, Christian Heck was granted a furlough of two weeks to help his family resettle after they lost their home. He took them to Bensheim, where Hannelore was, and they began to look for rooms. The housing shortage in Germany at the time was acute and it seemed as if nothing was available to refugees. At one point, Brother Heck stood for a moment deep in thought and then said, “Let’s go ask at that house,” pointing to a building near the railroad station. Sure enough, the owner had rooms to rent. They were assigned one large room and one small room with a bathroom downstairs. Annaliese attributed the discovery to her father’s inspiration.

As a POW of the Soviets, Karl Heimburg had some terrifying experiences. He and his comrades were marched as far as seventy-five miles in a day, and some of them made the trek with no boots. They were robbed of their valuables and any good articles of clothing. For days on end, they consumed nothing but snow. Those prisoners who fell down were simply shot. On one occasion, their captors drove by in American vehicles, dumped gasoline on some of the prisoners and set them on fire. On another occasion, Karl watched as Soviet tanks veered off the road now and then to run over and crush German POWs. During one stint in a camp in Estonia, only seven thousand of eighteen thousand German prisoners survived.

Back in Frankfurt, Karl’s mother was not aware that her son was a prisoner in Russia. In fact, she received an odd letter from Karl’s company commander stating that Karl was missing and asking her to contact the army if she knew the whereabouts of her son. The letter did not suggest that Karl was dead. It would be nearly three more years before Sister Heimburg learned that her son was alive.

Babette Rack (born 1909) was the mother of five little children when the war began. Like so many other mothers, she essentially raised her children alone after her husband was drafted into the army. In 1944, Sister Rack’s situation changed drastically, as she recalled:

I was bombed out on March 18, 1944. All we had left were the clothes on our backs—not even a teaspoon or bedding. For seven hours, we sat in an air-raid shelter on Schwanenstrasse in the Ostend neighborhood, unable to get out; the exit was blocked by debris. By the time we got out, the entire neighborhood along the Zeil [street] was burning. That afternoon, they put us up in the prison on Starkestrasse—not in the cells but in the hallways. We spent two days there. Then they sent us to the Liebfrauen School gymnasium. From there I was evacuated to Birklar in Giessen County. There was no place to attend church nearby and that was my situation for quite a while. [31]

For the Rack family and many other families all over Germany and Austria, one of the worst aspects of the war was their isolation from the Church.

Fig. 6. This public air-raid shelter in northwestern Frankfurt was painted to represent an apartment house that had been attacked and was burning, apparently in an attempt to deceive enemy dive-bombers looking for targets. (R. Minert, 1973)

Fig. 6. This public air-raid shelter in northwestern Frankfurt was painted to represent an apartment house that had been attacked and was burning, apparently in an attempt to deceive enemy dive-bombers looking for targets. (R. Minert, 1973)

Several families in the Frankfurt Branch experienced close calls during air raids. For example, Hermann Walker recalled, “One time, my mother and sister went upstairs again after [the raid] was over and found the bedroom on fire. Our furniture was damaged. The bomb had gotten stuck. They poured two buckets of sand over it and that [put it out].” Fortunately, the family had followed government instructions and prepared to fight fires on their own. Professional firefighters were rarely available under such circumstances.

The air raid of March 22, 1944, was not as merciful to the Walker family or to Hermann personally, as he recounted: “Our house was hit very badly. I lost my friend in that air raid. Three houses totally collapsed. There were two bombs—one fell on the street, and the other one hit the house in which my friend lived. It went all the way down to the basement and exploded there. My friend was not a member of the Church, but he was a very good friend.” [32]

In about 1944, Maria Schlimm was sent to live with her mother’s friends in Sprendlingen, a small town about seven miles south of Frankfurt. She had already spent two years away from home with relatives and was twenty when she arrived in Sprendlingen. Wanting very much to continue attending church meetings, she rode her bike back to the city on several Sundays.

The meeting rooms at Neue Mainzerstrasse 8–10 were destroyed during one of the many air raids after 1939, but the branch had already been asked to leave. The Saints met at several different locations near the center of town, such as in an unknown location on Hochstrasse, in a building on the corner of Neue Mainzerstrasse and Neuhofstrasse, in the Weissfrauen School on Gutleutstrasse, in the Rumpelmeier Kaffeehaus next to the city theater, and finally in the West German Mission office at Schaumainkai 41 on the south bank of the Main River. [33]

Fig. 7. This clock belonged to the Heinle family of the Frankfurt Branch. When their apartment building collapsed, the clock fell two stories into the basement. Upon locating it amid the rubble, the family found that the clock showed only a few scratches from the experience. (R. Minert, 2008)

Fig. 7. This clock belonged to the Heinle family of the Frankfurt Branch. When their apartment building collapsed, the clock fell two stories into the basement. Upon locating it amid the rubble, the family found that the clock showed only a few scratches from the experience. (R. Minert, 2008)

In Hirsau, refugees Erna Huck; her son, Jürgen; and her father, Friedrich Wagner were far from their home branch, but there was a branch of the Church in Pforzheim, twelve miles to the south. There was no direct public transportation to Pforzheim on Sundays, and it was too far for little Jürgen Huck to walk. However, Friedrich Wagner (an elder and former president of the Frankfurt District) was undaunted and made the trip to Pforzheim on foot, walking three hours each way. This connection to the Church ceased when the inner city of Pforzheim was reduced to rubble in a single air raid in April 1945. The Hucks and Friedrich Wagner could not attend another LDS Church meeting until 1947.

Fig. 8. Another piece of furniture rescued from the rubble by the Heinle family. (R. Minert, 2008)Still working in the mission office in 1944, Ilse Brünger Förster was informed by the government that she was required to take on additional employment. She was fortunate to find a job just around the corner, one requiring her to work only three hours per day for a transportation company. “The owner of the company soon found that he could trust me,” recalled Ilse, “so I did all the correspondence on my own and he paid me a good salary. In everything I did, I felt God’s hand.” [34]

Fig. 8. Another piece of furniture rescued from the rubble by the Heinle family. (R. Minert, 2008)Still working in the mission office in 1944, Ilse Brünger Förster was informed by the government that she was required to take on additional employment. She was fortunate to find a job just around the corner, one requiring her to work only three hours per day for a transportation company. “The owner of the company soon found that he could trust me,” recalled Ilse, “so I did all the correspondence on my own and he paid me a good salary. In everything I did, I felt God’s hand.” [34]

Otto Förster’s unit was transferred to the Netherlands in September 1944 to help defend the region near Arnhem against the Allied invasion launched under the code name Market Garden. Arriving after the Germans had crushed the invasion, Otto was moved into Germany. Driving his truck to transport supplies to German defenders during the Battle of the Bulge in December, he was attacked from behind by dive bombers. He saw people at the sides of the road scatter in all directions, but he did not know that they (and his truck) were under attack until his soldier passengers told him about it a few minutes later. [35]

At Christmas time in 1944, Otto found himself close to Herford and stopped in to see his daughter and his relatives. They had been bombed out and moved to another town a dozen miles away, where he was fortunate to find them. His arrival came as a total surprise, which was the case a few days later when Ilse arrived from Frankfurt, also unannounced. They were thrilled to spend a day or two together before he returned to his post west of the Rhine River. [36]

Toward the end of 1944, the Uhrhahn family was together again in Serbia, living well out of town in a small railroad shed. As the German lines began to crumble, partisans in the region became increasingly bold, and one day the entire Uhrhahn family was surrounded by combatants. Several of the men spoke German and it was apparent that they were bent on destroying a railroad tunnel and capturing a large payroll shipment. Wolfgang recalled that day’s events as follows:

The partisans put [Mother, Vera, and me] in our house and made my father and his workers carry dynamite about one-half mile to the tunnel. They put a box of dynamite on the tracks by the tunnel entry and wanted to run over it with a locomotive and blow up the train and the tunnel. My father pushed the dynamite off to the side and the locomotive got through and somehow word went out to the local German army command to come help us. They got there in time to save us. I even kicked a partisan in the shin because he was trying to molest my mother or something like that. The story of my resistance made it all the way up to the German high command, and my mother got a letter about me being such a brave boy.

Lola Uhrhahn and her children were then sent off to Hohenfeld, Bavaria, and her husband’s working conditions continued to deteriorate. In a hectic surprise attack, Hans Walter Uhrhahn and all of his office staff were captured by the enemy. His last letter was somehow smuggled out of the area and reached his wife, and then all communications were cut off. One of the secretaries later escaped and eventually told the story to Luise; apparently there was a break-out and Walter and his comrades scattered in all directions. The secretary saw Walter running toward a forest and he may have escaped, but nothing was ever heard from him again. Despite the desperate hopes and prayers of a loyal wife and adoring children, no word of Walter’s condition ever reached the family.

In the last year of the war, some Latter-day Saints in Frankfurt held meetings in their homes on Sundays. Carola Walker recalled doing so in their apartment on the outskirts of town. “Later on, we met in the mission home.”

After losing their apartment, Martha Walker and her children stayed with relatives in Frielingen, about eighty miles northeast of Frankfurt. According to her son Hermann, it had taken fully three days in March 1944 to make the relatively short trip to Frielingen after their house was destroyed. “We packed everything we could carry and left [Frankfurt]. The trains moved only at night; they didn’t want to be seen by enemy airplanes.” Although she saw no fighting on the ground, Carola Walker watched American airplanes over Frielingen: “Whatever wasn’t destroyed yet got destroyed then,” she explained. [37]

Fig. 9. Hermann Huck as a Wehrmacht soldier. (E. Wagner Huck)

Fig. 9. Hermann Huck as a Wehrmacht soldier. (E. Wagner Huck)

Younger brother Karl Walker did not feel at home in Frielingen: “[Our relatives] were like strangers to me. Even their dialect was different and they made fun of how I talked.” The small-town schoolteacher was an ardent supporter of the Nazi Party and required the children to greet her with “Heil Hitler” every morning. “We also had to pray that the Führer might be safe and well and that Germany would gain the final victory,” Karl explained. That teacher died and was replaced by one who had to ride the train every morning. “Sometimes she would fall asleep and miss her stop. By the time she got to the classroom, we were usually gone.”

The foreign soldiers held as POWs in homes and barns near Frielingen apparently represented a particular fascination for Karl. “We were very curious about the American soldiers, because they indicated that they were hungry and wanted food. They traded things for food. I remember that once when we gave them food, we got a football in return. For us kids, a ball was a ball, so we played soccer with it, but it didn’t work too well.” Karl explained that there were also French and Russian POWs in the area, but the children did not talk with them. “We were scared of them. The Americans were friendlier.”

Louise Hofmann Heck was as dedicated to the Church as her husband, Christian. In Bensheim she was miles from the nearest branch and did her best to keep the faith alive in their little apartment. Then she learned that the Marquardt family of the Darmstadt Branch lived just seven miles away, but those were uphill miles into the Odenwald Forest to the town of Gadernheim. According to Annaliese, “Brother Marquardt was an old man. We knew him because he had a beard and he gave a prayer at every conference. There were no buses operating on Sundays, so we walked to his home. It took about three hours each way. Even though my youngest sister, Christa, was only about four years old, she walked all the way. She didn’t have to be carried.”

As a soldier, Christian Heck became seriously ill in Russia and was sent to a hospital in Germany. By the time he had recovered, it was early 1945 and he was sent to a unit in southwestern Germany, where they faced the invading American army. In April, he was shot in the stomach and was carried by a comrade to a Catholic hospital, where he was given excellent care. Although he survived major surgery, he died of heart failure on April 19, 1945. That same comrade eventually made his way to Bensheim, where he informed Louise Heck of the death of her husband. Hannelore recalled one of her father’s last comments at home: “He said something to me once that stuck with me. ‘I’m not going to kill anybody—but somebody will have to kill me.’”

The minutes of the Frankfurt Branch meetings include the following statement on February 7, 1945: “A bomb landed in the yard behind the mission home; there was no real damage.” [38] Indeed, the mission home survived the war with only a few broken windows. By the spring of 1945, several families of the Frankfurt Branch had moved into the mission home after losing their own homes. The building was quite large, and there was plenty of room for refugees. The branch clerk added the following statement to the record as the war drew to a close: “March 8 to April 14, 1945: The mission home was occupied by American soldiers. Foreigners got into the basement and stole many valuable items. Later we determined that some important records were missing, leaving significant gaps.” [39]

Otto Förster seemed to be leading a charmed life. When his truck broke down in late February 1945, he had to leave it in a repair shop in Bonn. He recalled:

They told me they would need at least a week to fix it. For a week, with nothing to eat, I decided to go home. I went home to Frankfurt and carried all my papers with me. I went to the main train station, where the military checkpoint was located, and reported there because I wanted to make sure they knew that I wasn’t running away.

While he spent the next few weeks in the mission office with his wife, he learned that the invaders had crossed the Rhine and his return to Bonn was impossible. Changing to civilian clothing, he stayed with his wife and awaited the arrival of the Americans. [40]

Maria Schlimm recalled that in the last months of the war, families whose homes were destroyed or damaged often suffered from shortages or outages of utilities: “Large trucks came to bring water and people waited in long lines. During the night, the water was running at a trickle, and we used the opportunity to fill pots and pans. By the end of the war there was no electricity, and sometimes it was turned on for just an hour.”

When the American army approached Frankfurt in March 1945, Maria went with her family east to Hanau to the farm of a branch member’s brother. There they hid until they saw black GIs searching the homes for German soldiers. “I had never seen dark skin in my life before but I knew that it existed. I was not scared of them.”

Lola Uhrhahn and her two children spent the last months of the war near Hohenfeld. Life in the small town was very quiet in the spring of 1945, but Wolfgang recalled two events of significance. On one occasion, an enemy fighter plane zoomed down toward him while he was playing with friends. In his words, “We were kids, so we thought he wouldn’t shoot at us, but we were wrong. I suppose fighter planes can’t tell whether you are kids or adults.”

Once, a railroad train plunged off of a damaged bridge, and Wolfgang and his friends went out a few days later to see what treasures they might find in it. Wolfgang pulled on the handle of a door, and the entire door came off the hinges. “The door fell on my back. They had to carry me back to our raft and float me back across the river because I couldn’t walk.” Fortunately he was not badly injured.

Hohenfeld was so quiet that the invading American army caught the local residents totally by surprise. Sister Uhrhahn and Wolfgang were inside the small Gasthaus, where they had been given a room, and four-year-old Vera was playing outside. An enemy tank came around a corner and headed downhill toward the Gasthaus, where the road curved. When the tank’s treads began to slide on the wet road, the tank missed the turn and slid off the road straight ahead toward the Gasthaus. The tank’s long cannon barrel pierced the wall of the Gasthaus, and the vehicle came to a halt when the treads hit the building’s outside wall—with little Vera standing precisely between the treads against the wall, safe and sound.

The war ended in Hirsau with the arrival of French and Moroccan troops in the spring of 1945, but the hardships for refugee Erna Huck did not end. For weeks, the locals were subjected to abuse at the hands of the conquerors. According to Sister Huck,

The Moroccans raped every female from teenagers to eighty-year-olds. My cousin and I were spared because there was a French woman working in my aunt’s home. She went out and offered the home to the French officers [as a place to live] so the common soldiers couldn’t come in. The soldiers took our bicycles, cameras, jewelry, etc. (they had watches all up and down their arms) but they didn’t harm us. I worked in the house as a cook and served meals [to the French] until they got too “touchy,” and then I quit.

When American soldiers inspected the building in which the mission office was housed, they liked both its location next to a major Main River bridge and its condition (being one of the few intact structures in the neighborhood). They commanded the inhabitants to leave within thirty minutes. Otto Förster and his wife found a place to live with several other families in a one-room apartment down the street. Nearly two months later, they were allowed to return to their rooms at Schaumainkai 41. In the interim, Ilse had been hired by the American army to work as a translator because she spoke English and French. With a secure place to live and employment (soon for Otto as well), the Försters retrieved their daughter from Herford and began a new life together in the mission home. [41]

With the war over, Hans Mussler’s music school was closed and the pupils simply dismissed. Amid the confusion of the end of the Third Reich and the military occupation, each boy was expected to find his own way home. Although only ten years of age, Hans was ready for adventure and boarded a train headed west toward Ulm. At one point on the journey, he rode atop the train with his little suitcase. “That was very dangerous. There were power lines up there, and you had to keep your head down,” he explained. The train did not take him to Pforzheim, so he got off at Heidelberg and went looking for his aunt. Walking past the main cemetery, he saw a sight that could not easily be forgotten: the body of a German soldier hanging upside down from a tree. “It was shocking to see that.” Hans did not know at the time that summary executions of suspected traitors were happening all over Germany at the whims of fanatics.

While living in Heidelberg with his aunt, Hans came into contact with several LDS soldiers from the United States, and one of them baptized Hans in the summer of 1945. He was united soon thereafter with his mother, his sister, and his adoptive father, Franz Schmitt, who was eventually released from a POW camp in Great Britain.

Karl Heinle was inducted into the home guard at the end of the war, though he was over sixty at the time. His wife suggested that he leave his nice pocket watch at home because she felt that he would not need it. However, he took it along, and it served a crucial purpose: near Bad Mergentheim he was struck by shrapnel, a piece of which hit the watch and then ricocheted into his stomach. Fortunately he was not badly wounded, but the watch was ruined nonetheless.

When Elsa Heinle learned that her father was in a hospital in Bad Mergentheim, she tried to get there on the train. When this proved to be impossible, she got on her bike and rode there, a distance of nearly eighty miles. American army officials allowed her to visit her father in the hospital, and both were overjoyed at the reunion. When Brother Heinle was released, his wife’s relatives in the town took him in until he could safely travel back to Frankfurt.

When the American invaders approached Bensheim, some dangerous things happened. Dive bombers searched for local targets, and on one occasion a pilot shot at Annaliese Heck. She was hurrying to find a place to hide as the sirens wailed but was still in the open when the airplane’s guns opened fire. Huge 50-caliber rounds drilled a line of holes in a wall just above her head. “I was the only one near that spot, so I know that he was shooting specifically at me. I have no idea how he could have missed me when I [later] saw all of the holes in the wall.”

The Hecks were told by neighbors to flee to the Odenwald Forest. Fearing that looters would take what little property they had left, the Hecks chose to stay in their Bensheim apartment and were fortunate to learn that the conquerors were not bent on destruction. They had previously dropped flyers encouraging the people of Bensheim to surrender without a fight, and the Hecks were determined to do so. However, if they hung out a white flag, they could be accused of treason and shot by local fanatics. Annaliese had the clever idea of washing their white sheets and hanging them out to dry at precisely the right time. “It wasn’t my idea,” claimed Annalies Heck. “You know where that idea came from.”

Hannelore also clearly remembered the arrival of the Americans:

I was not scared to see the Americans. We knew that they were approaching. The shooting finally stopped and we were wondering why we could not hear them anymore. But then they [suddenly] came in—and we knew why [we didn’t hear them]. They were wearing rubber soles, which made it impossible for us to hear them walking. But there was no fighting. . . . When they came in, we were in the house and waiting to see what would happen, but we were not afraid. Fortunately, I spoke English, which I had started learning when I was ten years old. Some of the soldiers came into our home, and they were quite startled to find English-speaking German girls like my sister and me.

Regarding the war experience in general, Hannelore Heck made this comment: “You pulled yourself together for the sake of others. We tried to be strong for each other so that the other person, and especially our parents, would not feel bad. . . . I didn’t want my mother to suffer more than she already had to because of the war and my father being gone.”

As in most branches of the West German Mission, the Saints in Frankfurt did their best to continue holding meetings when the war ended. On May 27, the meetings were visited by two American soldiers named Cannon and Taylor. At the time, only about fifteen persons were gathering on Sundays. On July 1, Hermann Ruf was again called to serve as the branch president. The search for a new meeting place also began. [42]

Looking back on the war years, Elsa Heinle recalled that her family often could not get to the meetings until the last months of the war. “There were always priesthood leaders on hand to preside over meetings and to administer the sacrament, but the number of members present declined steadily. We took care of each other and visited each other to see what we could do to help. . . . I had a strong testimony of the gospel and the war did nothing to change that.”

Carola Walker, who had been baptized at the age of eight, recalled, “I was always active in the Church. I did whatever I could to help in the branch. That helped me to keep going through the difficult conditions.”

At one point during his Soviet captivity, Karl Heimburg heard a call for mechanics. He volunteered and was assigned to drive a truck. This activity took him all over the region as he hauled lumber, coal, cement, “and you name it!” Because he was always good at learning new languages, he picked up Russian quickly and got along quite well in the camps. He even earned a bit of money during his last year as a prisoner. “I fed a lot of people with that money,” he said.

Toward the end of June 1949, Karl was released from prison and transported to Frankfurt an der Oder—in eastern Germany, just across the river from Poland. He recalled, “They gave us each ten East German Marks, a pound of sugar, and a telegram to send home.” He immediately sent the telegram and then made his way back to his mother and siblings in Frankfurt am Main. Soon after his return, he saw his friend Annaliese Heck for the first time in more than seven years. According to her, “I had never asked his mother whether he was alive because I was afraid that it might open old wounds.” Karl and Annaliese married soon after this reunion.

Hermann Huck had been taken prisoner by the Americans just before the war ended and was later turned over to the French. For quite a while, he could not contact his wife to tell her that he was still alive. He finally learned of his family’s whereabouts and joined them in Hirsau. In 1947, they returned to Frankfurt and attempted to claim their previous apartment. They were refused, but then were given twenty-four hours to move their remaining furniture to a different location in the city. They made the move successfully and began a new life in their hometown.

A German court declared Hans Walter Uhrhahn officially dead in the early 1950s. The date established for his death was September 30, 1944. No place of death was specified.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Frankfurt Branch did not survive World War II:

Alfred Ausserbauer b. Buer, Buer, Westfalen, 1 Mar 1924; son of Georg Ausserbauer and Katharina Bach; bp. 14 May 1932; conf. 14 May 1932; k. in battle Normandy, France, 22 Jun 1944 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 6; CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, pp. 289–99; branch membership record book 2)

Sophie Ausserbauer b. Merlenbach, Forbach, Elsaß-Lothringen, 27 Apr 1914; dau. of Georg Ausserbauer and Katharina Bach; bp. 17 Jul 1922; conf. 17 Jul 1922; m. 20 Mar 1937, Ernst Wilhelm Clemens; d. meningitis 4 Aug 1943 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 350; book 1)

Olga Amalia Bachmieder b. Weissenhorn, Memmingen, Bayern, 29 Jan 1874; dau. of Joseph Bachmieder and Rosina Viedmann; bp. 16 Sep or Oct 1920; conf. 16 Sep or Oct 1920; m. —— Yoos or Fost; d. stomach cancer 5 May 1940 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 162; branch membership record book 1; FHL microfilm 68791, no. 279; IGI)

Herbert Brandelhuber k. in battle (E. Wagner)

Wilhelm Breitwieser b. Dieburg, Hessen, 29 Jun 1867; son of Konrad Breitwieser and Katharina Heil; bp. 14 Jul 1914; conf. 14 Jul 1914; d. senility Oberkochstadt, 30 Dec 1944 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 21; branch membership record book 1; IGI)

Eugen Dommer b. Offenbach, Hessen, 14 Dec 1910; son of Alfred Dommer and Barbara Klesius; bp. 16 Jun 1929; conf. 16 Jun 1929; m. 30 Apr 1935, Erna Maria Becht; k. in battle Hermsdorf, Apr 1945; bur. Halbe, Teltow, Brandenburg (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 284–85; FHL microfilm 68791, no. 293; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Christine Karoline Graf b. Jagsthausen, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 29 Feb 1856; dau. of Johann Georg Graf and Magdalene Henriette Platscher; bp. 15 Jun 1903; conf. 15 Jun 1903; m. —— Waibel; d. senility 3 Feb 1943 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 160; branch membership record book 1; IGI)

Maria Grebe b. Caldern, Marburg, Hessen-Nassau, 7 Jul 1874; dau. of Johann Peter Grebe and Katharina Junk; bp. 12 Jul 1923; conf. 12 Jul 1923; m. Braunschweig 1 May 1893, Johann Heinrich Jung; d. 29 Mar 1942 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 85; branch membership record book 1; see Frankfurt District book 1; LR 2986 11, 153; FHL microfilm no. 271375, 1925 and 1935 censuses)

Frida Maria Haagen b. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 29 Jan 1907; dau. of Friedrich Otto Edward Haagen and Anna Margarete ——; m. Frankfurt/

Karl Hermann Haug b. Frankfurt/

Christian Karl Henry Heck b. Frankfurt/

Josef Heck b. Mainz, Rheinhessen, Hessen, 16 Jul 1871; son of Karl Josef Heck and Margarete Knaf; bp. 13 Mar 1898; conf. 13 Mar 1898; ord. elder 26 Feb 1905; m. Frankfurt/

Georg Heil b. Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 1 Oct 1918; son of Johann Wilhelm Heil and Friederika Luise Hohlweger; bp. 29 Mar 1935; corporal; k. in battle Ljadno, Tschudowo, Russia, 3 Apr 1942 (CHL microfilm 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 1949 list, 2:44–45; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Ludwig Hofmann b. Bürgstadt, Aschaffenburg, Bayern, 3 Oct 1892 or 1894; son of Adalbert Hofmann and Marie Rosine Eckert; bp. 25 May 1925; conf. 25 May 1925; ord. deacon 11 Apr 1926; ord. teacher 24 Apr 1927; ord. priest 7 Oct 1928; ord. elder 22 May 1932; m. 20 Mar 1915, Emilie Katharina Auguste Wolf; two children; d. stomach cancer Rödelheim, Frankfurt am Main, Hessen-Nassau, 2 Aug 1942; bur. Rödelheim, Frankfurt am Main (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 65; LR 2986 11, 155; branch membership record book 1)

Emma Höll b. Achern, Baden, 22 Aug 1879; dau. of Ludwig Höll and Viktoria Oberle; bp. 22 Jun 1912; conf. 22 Jun 1912; m. Frankfurt/

Frank Heinrich Thomas Humbert b. Frankfurt/

Waldemar Herbert Kalt b. Seckenheim, Mannheim, Baden, 6 Aug 1911; son of Adam Kalt and Wilhelmine Amalie Luise Frank; bp. 22 Oct 1921; conf. 22 Oct 1921; d. work accident 28 Nov 1939 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 88; branch membership record book 1; IGI)

Willy Klappert b. Ferndorf, Siegen, Westfalen 25 Jul 1914; son of August Heinrich Gustav Klappert and Auguste Dickel; bp. 1 Sep 1929; conf. 1 Sep 1929; ord. deacon 1 Nov 1938; corporal; k. in battle Jegiorcive 2 Sep 1939; bur. Mlawka, Poland (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 298; www.volksbund.de; branch membership record book 1; IGI, AF)

Elisabeth Leng or Läng b. Hochstein 25 Jan 1868; m. Georg F.a. G.H.P.D.M. Kretzer; d. 10 Feb 1941; bur. Frankfurt/

Camilla Meta Lorenz b. Pirna, Dresden, Sachsen, 13 or 15 May 1893; dau. of Gustav Adolf Lorenz and Klara Walther; bp. 31 Jul 1937; conf. 31 Jul 1937; m. Georg Böhm; k. in air raid Frankfurt/

Marie Therese Mellinger b. Bockenheim, Frankfurt/

Paula Merle b. Frankfurt/

Anna Barbara Müller b. Hütten, Neustettin, Pommern, 28 Apr 1870; dau. of Niklaus Müller and Elisabeth Knauf; bp. 30 Sep 1927; m. —— Makko; k. air raid Frankfurt/

Walter Münkel b. Frankfurt/

Maria Katherina Rosina Naumann b. Hanau, Hanau, Hessen-Nassau, 8 Aug 1868; dau. of Stephan Naumann and Eva Rosenberger; bp. 16 Oct 1928; m. Johann Glock; d. 31 Oct 1940 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 330; book 1, IGI)

A. Margarethe Noll b. Simmern, Koblenz, Rheinprovinz, 30 Jan 1861; dau. of Karl Noll and Anna Sahl or Sabl; bp. 26 Jun 1912; conf. 26 Jun 1912; m. Josef Elter; d. senility 26 Jun 1940 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 39; book 1; IGI)

Heinrich Ludwig Persch b. Kassel, Hessen, 1 May 1879; son of Johann Georg Persch and Theodora Helm; bp. 4 Aug 1932; conf. 4 Aug 1932; d. 12 Oct 1944 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 388; Frankfurt District book 2)

Margarethe Katharina Emma Repp b. Fischborn, Unterreichenbach, Hessen-Nassau, 15 Mar 1890; dau. of Heinrich Repp and Maria Schärpf; bp. 1 Feb 1926; conf. 1 Feb 1926; m. —— Krieg; d. pulmonary tuberculosis 19 Apr 1942 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 107; book 1; FHL microfilm 271381, 1925 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Dorothea Gisela Ruf b. Frankfurt/

Wilhelm Heinrich Melchior Scheel b. Frankfurt/

Ludwig Schiffler b. Uchtelfangen-Kaisen, Ottweiler, Rheinprovinz, 20 May 1867; son of Johann Valentin Schiffler and Katharina Henriette Ulrich; bp. 15 Mar 1910; conf. 15 Mar 1910; ord. elder 29 Nov 1931; d. senility 15 Feb 1941; bur. Frankfurt/

Elisabeth Schönhals b. Friedberg, Gießen, Hessen 16 Dec 1865; dau. of Johannes Schönhals and Marie Kimball; bp. 7 Nov 1924; conf. 7 Nov 1924; m. —— Bilz; d. senility Köppern, Wiesbaden, Hessen-Nassau, 14 Feb 1943 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 16;branch membership record book 1; IGI)

Ernst Albert Schubert b. Treuenvolkland(?), Frankfurt/

Elisabeth Seng b. Hochstein, Rockenhausen, Pfalz, Bayern, 25 Jan 1868; dau. of Heinrich Seng and Magdalena Sauer; bp. 25 May 1925; conf. 25 May 1925; m. —— Kretzer; d. heart failure 10 Feb 1941 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 106; book 1)

Wilhelm Friedrich Steingrand b. Würzburg, Bayern, 27 Mar 1914; son of Katharina Wagner; bp. 1 Feb 1926; conf. 1 Feb 1926; k. in battle 4 Jan 1941 (FHL microfilm 68791, no. 205; LR 2986 11, 151; book 1)

Wilhelmina Elisabeth Stuber b. Laufenselden, Untertaunuskreis, Hessen-Nassau, 9 Aug 1863; dau. of Johann Philipp Stuber and Catharina Louise Kalteyer; bp. 22 Mar 1903; conf. 22 Mar 1903; m. 27 Sep 1881, Peter Hermann Schuessler; two children; 2m. Frankfurt/

Hans Johann Uhrhahn b. Essen, Essen, Rheinprovinz, 22 Jul 1904; son of Heinrich Uhrhahn and Wilhelmine Kunz; bp. 5 Apr 1919; conf. 5 Apr 1919; m. Frankfurt/

Alfons Wahl b. Rulfingen, Sigmaringen, Hohenzollern, 5 Apr 1890; son of Joseph Wahl and Josephine Oft; bp. 12 May 1920; conf. 12 May 1920; k. air raid Frankfurt/

Augusta Wicki b. Westerhof, Osterrode/

Notes

[1] Frankfurt city archive. The autobahn route ran from Frankfurt eighteen miles directly south to Darmstadt. Finished in 1937, it was hailed far and wide as the finest highway in Europe. The autobahn construction was begun between Munich and Salzburg, but this stretch was not finished until 1938.

[2] Erna Wagner Huck, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, July 6, 2006.

[3] Maria Schlimm Schmidt, interview by the author in German, Frankfurt, Germany, August 18, 2008; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[4] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[5] Hannelore Heck Showalter, telephone interview with the author in German, March 9, 2009.

[6] Hermann Friedrich Walker, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, March 6, 2009.

[7] Carola Walker Schindler, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, March 6, 2009.

[8] Otto Förster, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, Utah, November 28, 2009.

[9] Karl Heinz Heimburg, interview by the author, Sacramento, California, October 24, 2006.

[10] Annaliese Heck Heimburg, interview by the author, Sacramento, California, October 24, 2006.

[11] See the photograph by Erma Rosenhan in the Offenbach Branch chapter.

[12] See the West German Mission chapter.

[13] Ilse Brünger to M. Douglas Wood, August 28, 1939, M. Douglas Wood, papers, 1927–40, CHL MS 10817.

[14] Ursula Mussler Schmitt, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, March 31, 2009.

[15] Hans Mussler, interview by the author, Preston, Idaho, November 22, 2008. See the Bühl Branch chapter for more on Hans’s experience in the Church.

[16] Frankfurt Branch general minutes, 144, 151, 155–56, LR 2986 11.

[17] Frankfurt Branch general minutes.

[18] Ilse Wilhelmine Friedrike Brünger Förster, autobiography (unpublished, about 1981); private collection.

[19] Offenbach Branch general minutes, CHL LR 6389 11.

[20] Wolfgang Uhrhahn, interview by the author, Cottonwood Heights, Utah, February 6, 2009.

[21] Karl Walker, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, March 13, 2009.

[22] See the introduction for more details about such precautions that were carried out all over Germany and Austria.

[23] See the West German Mission chapter for more details about Ilse Brünger Förster’s work at Schaumainkai 41.

[24] Otto Hugo Förster, autobiography (unpublished, 1998); private collection.

[25] Elsa Heinle Foltele, interview by the author in German, Frankfurt, Germany, August 19, 2008.

[26] Frankfurt Branch general minutes, 167.

[27] Ibid., 173.

[28] Ibid., 173.

[29] Ibid., 174.

[30] Ibid., 174–76.

[31] Babette Rack, 110 Jahre (1894–2004) Gemeinde Frankfurt, 112–13, CHL.

[32] This was a common occurrence with explosive bombs. In older homes, the roofs and floors on the various levels were often not solid enough to activate the fuse, so the bomb went off only when it hit the concrete floor of the basement; then the entire structure collapsed.

[33] Rock, 110 Jahre Gemeinde Frankfurt, 9.

[34] Ilse Brünger Förster, autobiography.

[35] Otto Förster, interview.

[36] Otto Förster, autobiography.

[37] Hermann’s sentiments about church attendance were similar to those expressed by many eyewitnesses in this study: “Whoever really wanted to attend church meetings found a way to do it.”

[38] See the West German Mission chapter for details about that specific air raid. Eyewitness Otto Förster recalled much more damage: all exterior and some interior windows were broken, and two bombs bounced off of the exterior walls without exploding. An artillery shell entered the corner office, tore through the floor into the basement, and exploded.

[39] Frankfurt Branch general minutes, 177–78.

[40] Otto Förster, interview.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Frankfurt Branch general minutes, 178–79.