Frankenburg Branch

Roger P. Minert, “ Frankenburg Branch, Munich District,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 271–75.

The town of Frankenburg is located deep in the hills of the state of Upper Austria—as the crow flies twelve miles southwest of Haag am Hausruck and thirty miles northeast of Salzburg. With a population of less than a thousand inhabitants when World War II approached, it was an unexpected venue for a branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The mission directory for the branch in Frankenburg shows only a few offices assigned. Mathias Steindl was the branch president when the war began. The only other surnames that appear in the branch directory in 1939 are Altmann and Brückl. The meetings at the time were held in the Steindl apartment in house no. 61. According to branch meeting minutes of the war years, other members of the branch belonged to the Limberger and Schachl families.

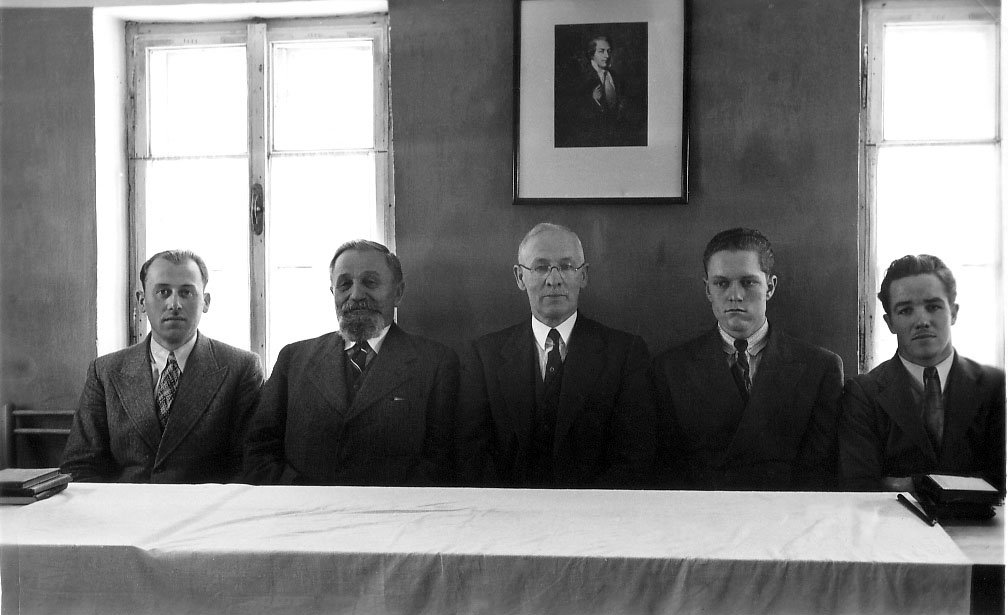

Fig. 1. Church leaders attending the dedication of the branch meeting rooms in 1938. Left to right: Joseph Grob, Georg Schick, Thomas E. McKay, Horace G. Moser, and Rao K. Parker. (G. Koerbler Greenmun)

Fig. 1. Church leaders attending the dedication of the branch meeting rooms in 1938. Left to right: Joseph Grob, Georg Schick, Thomas E. McKay, Horace G. Moser, and Rao K. Parker. (G. Koerbler Greenmun)

The faithful Saints in Frankenburg were physically isolated but by no means forgotten. The branch meeting minutes show a great number of visitors coming and going from 1938 to 1940 when the records end. West German Mission president M. Douglas Wood and his wife were there in 1938, as was Vienna District president Georg Schick. After the branch was transferred to the Munich District, president Hans Thaller came for visits on at least five occasions. Presidents Franz Rosner and Rudolf Niedermair of the Haag and Linz Branches (respectively) also came, as did Georg Mühlbacher, president of the branch in Salzburg. Those visits were not made without sacrifice, however, because public transportation from the major cities to Frankenburg was not at all convenient. One of the last reported visits was by Anton Huck, first counselor to the mission supervisor in Frankfurt. [1]

| Frankenburg Branch [2] | 1939 |

| Elders | 0 |

| Priests | 1 |

| Teachers | 1 |

| Deacons | 0 |

| Other Adult Males | 2 |

| Adult Females | 9 |

| Male Children | 1 |

| Female Children | 1 |

| Total | 15 |

Because the branch was in a rural setting, communications were slightly slower. Thus American missionaries Nephi Henry Duersch and Robert J. Gillespie were probably the last to hear of the evacuation of foreign missionaries from all of Germany and Austria one week before the war began. Returning to their apartment in Frankenburg from a lengthy bicycle tour in Haag and towns along the route, they found the telegram instructing them to leave on August 25. It was already September 2. They immediately left, taking a train first to Germany and then crossing the border south into neutral Switzerland. [3]

“They gave me a bicycle,” recalled Auguste (Gusti) Steindl (born 1928), “It was sad because we were very close to the missionaries. We didn’t have much [money] before the war, but we invited them for dinner. . . . It was a very nice time.” [4] Gusti had the following to say about her father, the branch president: “We read the Bible and the Book of Mormon, and my father was very strict about the Sabbath day. Oh my, I remember one time, my cousins came from the city, and they wanted to take me to a movie [one Sunday]. Oh, no! Those cousins didn’t talk to him for a long time after that.”

When the war broke out in September 1939, the branch in Frankenburg felt its effects immediately. President Steindl was drafted, but for a time was close enough to home to remain the leader of the congregation. In September, President Steindl purchased house no. 62 and moved his family in. Following “tremendous work” by the members, a storage room in the house became the meeting place. Soon thereafter, Brother Steindl was quoted as stating that “the branch has endured [difficulties] since 1937, but that the Lord has helped us to overcome all of those difficulties.” [5] Branch records show a total attendance at meetings during 1939 as 2,624, yielding an average attendance of fifteen persons at the 174 meetings. [6]

During the first month of the war, the sacrament meeting time was changed to 4:00 p.m. to accommodate the blackout regulations. The clerk kept very detailed records in those days, noting the names of speakers and their topics. The minutes of the Sunday School include the term Klassentrennung, meaning that the Saints separated into at least two groups for instruction.

The Frankenburg Branch was increased in size substantially by the arrival of the family of Franz Dittrich from nearby Haag in 1940. Margaretha Dittrich (born 1931) recalled the following about her father’s employment: “When we moved to Frankenburg in 1940, my father started working as a streetworker. He cleaned the streets, and that was difficult for him to do that work because he knew that he could do better. He never found work as a baker again.” [7] She also described the branch meeting rooms in Frankenburg:

We met in house no. 61 near the market square. We only had one room on the first floor. The Steindl family had their apartment in the same building. During the week, we also held Primary. We had benches and a pump organ. There were also pictures that we hung up. One of them was a picture of Jesus Christ on his knees praying in the Garden of Gethsemane. It was quite large. All of our neighbors knew that we were members of the Church and it did not matter to them.

Young Hildegard Dittrich (born 1927) was naturally worried about changing schools and leaving her dear friends in the Haag Branch. [8] She finished her public school experience in 1941 and was soon called upon to serve her Pflichtjahr on a farm in support of the national war effort. This service interfered with her plans to become a secretary.

After communications between the Saints in Europe and Church headquarters in Salt Lake City were interrupted in December 1941, the office of the West German Mission in Frankfurt was hard pressed to supply the branches with instruction manuals for Church programs. Hildegard recalled that her father “had to copy lessons for Sunday School out of very old Church books or Church magazines.” This did not last for long, however, because in the spring of 1942, Franz Dittrich (a veteran of World War I) was drafted into the Wehrmacht and assigned to work as a radio operator in the police office in Linz, forty miles to the east. He would remain there until the end of the war.

The records of the branch for the years 1940–41 include a discouraging note: apparently one of the women accused another of endangering her marriage. The accused demanded a retraction of the charge. The unidentified branch clerk added a note to the effect that he and his wife did not feel the Spirit of the Lord when entering the second sister’s house. The negative feelings were mentioned again on April 24, 1940. Months later, in January 1941, Anton Schindler, a veteran member of the Church from Munich, came with Franz Rosner of Haag “to help resolve differences in the branch . . . but left town without having achieved success in the conflict.” By May 3, 1941, the matter was resolved and a “nice spirit” prevailed. [9]

Following her Pflichtjahr, Hildegard Dittrich was pleased to find employment in the post office in Frankenburg. After work and on weekends, she was very busy with Church callings. Despite her age (she was only sixteen at the time), she served simultaneously as a Primary teacher, chorister or organist (on a pump organ), and Relief Society secretary and treasurer.

Hildegard later wrote that even though her father was away from home, the family had just enough to eat during the war years, but food was by no means easy to come by:

Every day very, very early in the morning, my sister Grete would go to the store and bakery and stand in line for a few hours so she could buy a loaf of bread for us or some sugar or flour or anything edible. Most of the time the bread in the store was already gone before she got to the counter, and so it was with everything else, and that went on for lots of days.

Along with her schoolmates, Margaretha Dittrich was inducted into the Jungvolk in 1941 at age ten. She described the experience in these words:

We had to attend the meetings, if we wanted or not, but we did not believe in it. We had church on Sunday mornings, so I did not go to the Jungvolk meetings. The leaders were angry and asked me at school where I had been. My parents were cautious and did not say anything about it. I had to justify why I missed the meetings. But I was always the black sheep anyway because of my religion, so it did not really matter. Later, I was a member of the League of German Girls. We got a brown jacket and had to know how to tie the knot a certain way. I burnt it after the war was over.

For young Margaretha, the political situation under Hitler’s Third Reich was not particularly impressive: “There were some members of the party in our branch but we did not talk about [politics] in church. And I never heard anybody pray for Hitler, but we prayed for the safety of all the soldiers.”

Although at first it seemed to Hildegard and her family that Germany would win the war, conditions changed, and it was clear that Hitler’s Third Reich was in trouble. In the last years of the war, Allied bombers came within range of Austrian cities, and they were bombed despite Austria’s status as a conquered nation. The Dittrich family covered their windows in response to blackout regulations and wondered if the many airplanes flying overhead would drop their bombs on the village of Frankenburg; fortunately, that never happened. Regarding their survival under the increasingly difficult conditions, Hildegard wrote, “We could do nothing but keep on working and doing our jobs in the branch and at work as good as we could. We prayed every day very hard to our Heavenly Father for His protection. We knew that He will bless us if we keep His commandments.” [10]

Fig. 2. The family of Franz and Margaretha Dittrich was baptized in late 1939. As Margaretha recalled, “It took place in Haag in the public pool. After the meeting on Sunday, we walked to the pool. But we had told the owner of the pool that we would come, so he let us be there alone. I was not the only one being baptized that day.” [11]

Fig. 2. The family of Franz and Margaretha Dittrich was baptized in late 1939. As Margaretha recalled, “It took place in Haag in the public pool. After the meeting on Sunday, we walked to the pool. But we had told the owner of the pool that we would come, so he let us be there alone. I was not the only one being baptized that day.” [11]

In a small town far from the war, life was a bit easier than in more critical locations. According to Gusti Steindl, it was still possible to be a teenager and have fun: “We went to dances sponsored by the Catholic Church. We still had parties, games, dates. Things just sort of went on as before. We were fortunate to be in such a quiet area.”

When all of the local priesthood holders were absent from Frankenburg, Heinz Jankowsky was assigned to visit the Frankenburg Branch and to administer the sacrament there. There was no cessation of worship services in the small branch during the war. The branch meeting minutes continued without interruption through the end of the war as if nothing out of the ordinary were happening. It is clear that the Saints were doing all that they could to maintain the Church in Frankenburg. The Relief Society records were also duly kept from 1940 to 1945 and state at the end of 1943, “The sisters set a goal to carry out their duties with greater dedication in the coming year.” Sunday School attendance was often less than ten persons, but the Primary reported attendance of from seven to thirteen children during the years 1940–41. [12]

According to Margaretha Dittrich, there was little danger to the residents of Frankenburg during the war: “We had some low flying planes [toward the end] but they didn’t damage anything. A real attack never happened in Frankenburg. But whenever we heard an alarm, we did go into a basement near our home to make sure we were safe.”

For Gusti Steindl, those fighter planes (Tiefflieger in German) represented a real danger: “[My mother] used to go in the morning to the farmers and collect the eggs. And one time when she was coming home, there was some airplanes flying over, and they started shooting at her. But that was the only time. Otherwise, I don’t remember anything really dangerous happening.”

By some quirk of fate, Franz Dittrich was able to negotiate the forty miles from the city offices of Linz to his home in Frankenburg amid the confusion of the last days of the war. The enemy did not take him prisoner. According to Margaretha, “My father was already home when [the invaders] came.”

Fig. 3. Franz Dittrich (left) served as a radio operator in Linz for the last few years of the war.

Fig. 3. Franz Dittrich (left) served as a radio operator in Linz for the last few years of the war.

In April 1945, the American army moved through Upper Austria. The invaders met little or no opposition and found no reason to disturb the residents, but they did use Frankenburg schools for their housing. As in many areas of western Germany and Austria, the residents saw black men for the first time. As Margaretha recalled, “When we saw the black people for the first time, we were scared. . . . But then we were told that they were good people, and then we trusted them. We got chocolate from them.”

“We didn’t hang out a [white] flag; everybody welcomed [the conquerors],” recalled Gusti Steindl. “We even had three or four soldiers in our home and they were very nice. My mother gave up the bedroom and the living room. . . . But some people were beaten by the Americans. I remember there was an old lady in a big restaurant, and they really whipped her. But one [soldier] protected us [from searches and drunkards]. And he brought us food—meat and sugar and stuff like that.”

By the end of the summer, all of Austria had been organized into four military occupation zones under American, British, French, and Soviet forces. During the transition, Hildegard Dittrich lost her job in Frankenburg and was sent to the post office in Salzburg. Afraid of the many soldiers in that big city, she asked to be released from her employment and was allowed to return home, where she found her father safe and sound. He had avoided becoming a POW, returned home safely, and had been assigned to lead the branch.

Among the occupying forces were several members of the LDS Church who soon located the branch meeting rooms and joined the local Saints in their meetings. They also brought food to share with their new friends. With peace restored, the branch in Frankenburg had survived, and the future looked difficult but bright.

No members of the Frankenburg Branch are known to have died during World War II.

Notes

[1] Frankenburg Branch general minutes, CHL LR 11253 11.

[2] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 721, CR 4 12.

[3] Terry Bohle Mantague, Mine Angels Round About, 2nd ed. (Orem, UT: Granite, 2000), 101–02.

[4] Auguste Steindl Rosner, interview by the author, South Jordan, Utah, March 2, 2007.

[5] Frankenburg Branch general minutes, 78.

[6] Ibid., 90.

[7] Margaretha Dittrich Schauperl, interview by the author in German,Frankenburg, Austria, August 7, 2008; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[8] Hildegard Dittrich Cziep, autobiography (unpublished); private collection.

[9] Frankenburg Branch general minutes, 128–29, 139, 158.

[10] Cziep, autobiography.

[11] Margaretha Dittrich Schauperl, interview by the author in German in Frankenburg, Austria, on August 7, 2008; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[12] Frankenburg Branch Primary Association minutes and records.