Feuerbach Branch

Roger P.Minert, “FeuerbachBranch,” in Under the Gun: West German and Austrian Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011), 420–426.

“The branch meeting rooms were in a Hinterhaus on Elsenheimsstrasse,” recalled Reinhold Rügner (born 1931). “We went through the main building at number 8, then across a courtyard and into the Hinterhaus. We had all of our meetings in one large room. There was room for forty to sixty people. We also used the foyer and the kitchen for classes. We didn’t have restrooms.” [1] Such was the setting of the Feuerbach Branch.

Hermann Mössner (born 1922) added the following details to his cousin’s description:

A family who belonged to the Apostolic Church owned the building. They were very religious people and strong members of their church. They allowed us to use their rooms but we were not allowed to dance or have dance lessons, which the young members of our Church always liked. The rooms were located near a chicken coop and every time we went to meetings, the chickens were very loud. It was not a very inviting atmosphere for Church meetings, but we accepted it. On the inside, the rooms were kept very simple. [2]

Barely three miles north of the center of Stuttgart, Feuerbach was nearly a suburb of the provincial capital. The branch there had sixty-three members and was in good condition in the summer of 1939. Reinhold’s father, Gottlob Rügner, was the branch president and was assisted by counselors Johann Buck and Hans Lang. Other branch leaders at the time were Hermann Mössner (YMMIA), Bretel Buck (YWMIA), and Maria Greiner (Relief Society). The branch president was also the genealogy instructor and Sister Greiner was the Stern magazine representative. There was no Primary organization at the time. [3]

| Feuerbach Branch [4] | 1939 |

| Elders | 7 |

| Priests | 1 |

| Teachers | 4 |

| Deacons | 2 |

| Other Adult Males | 7 |

| Adult Females | 36 |

| Male Children | 4 |

| Female Children | 2 |

| Total | 63 |

The meeting schedule shows several gatherings beginning at 8:00 p.m., such as the Relief Society on Mondays and the MIA on Tuesdays, which must have been slightly inconvenient for the branch members who lived in other towns around Feuerbach. The Sunday School began at 10:00 and was followed by priesthood meeting at 11:30, with sacrament meeting at 7:00 p.m.

Brother Rügner’s family walked about one hour to church from Weilimdorf. With eight children, there was not enough money to pay for a streetcar ride unless the weather was bad. According to Reinhold, “We walked there for Sunday School, then went home and came back later for sacrament meeting.” That would have amounted to four hours of walking each Sunday. He added, “One got used to it.”

Fig. 1. The Jungvolk group to which Reinhard Rügner belonged in about 1942. (R. Rügner)

Fig. 1. The Jungvolk group to which Reinhard Rügner belonged in about 1942. (R. Rügner)

Hermann Mössner recalled the beginnings of war in September 1939:

I was seventeen years old when World War II started, and for me nothing changed that much. But I remember that some members of our branch became members of the National Socialist Party and even brought their flag into the branch rooms. I remember the exact day that the war started in September of 1939. I was in the third year of my work training as a plumber, and we were working on a project when we heard that Adolf Hitler had declared the war at midnight the night before. It was such an uncertain situation for all of us, and we did not understand why there was a second war now [after Germany lost the Great War in 1918].

“I was baptized in either 1939 or 1940 in the Neckar River. It was summer and the water was warm. Karl Mössner baptized me, and he died as a soldier a little bit later [1941],” recalled Reinhold Rügner. By 1943, life in Weilimdorf was becoming difficult as attacks on Stuttgart threatened the towns nearby. Reinhold was evacuated with his class to the town of Kuchen, where the boys were taken in by local families. Reinhold lived with a widow from 1943 to 1944 and described the situation in these words:

During that year, I was never allowed to go home. Kuchen is about forty miles away from our home. My mother was also not able to visit me during that time. We did not have the financial means. My father was assigned to visit the Göppingen branch every month or so. On those Sundays, I took the train from Kuchen to Göppingen so that I could attend the meetings with him. I looked forward to those days because I could see a member of my family.

In 1944, Reinhold was sent to a higher-level school in Nürtingen near the Neckar River: “It was a school that was mostly run by the party. They used it to train their future party members, but it was not official. We stayed in boarding schools. My plan was to finish the degree and then work in the government somewhere later on.”

Hermann Mössner was old enough to be drafted by 1942, but his work in a munitions factory in Feuerbach allowed him an exemption. During those years, he often attended branch meetings in Stuttgart when he was off duty. In July 1944, he emerged from a shelter where he had spent many hours during what he called “the heaviest attack on Stuttgart” to find that the rooms of the Stuttgart Branch had been totally destroyed. Because his own apartment was also destroyed, he returned home to live with his parents. By September, he was in the uniform of the German Wehrmacht: “I left my wife with tears in my eyes. We were married for only a few weeks.” After an abbreviated training period, he was sent off to the Western Front.

As a forward observer in lines opposing British troops, Hermann’s responsibility was to report the movements of the enemy. He was so close to the action that while he and his comrades were sheltered in the basement of a house, a British tank ran over the building. Hermann was not harmed, but he was found by the enemy later that day and taken prisoner. It was November 18, 1944, near the city of Aachen, Germany. One month later, the fierce Battle of the Bulge would begin very close to that city; Hermann was safer as a POW. From the first camp in Belgium, he was moved to another in Leeds, England.

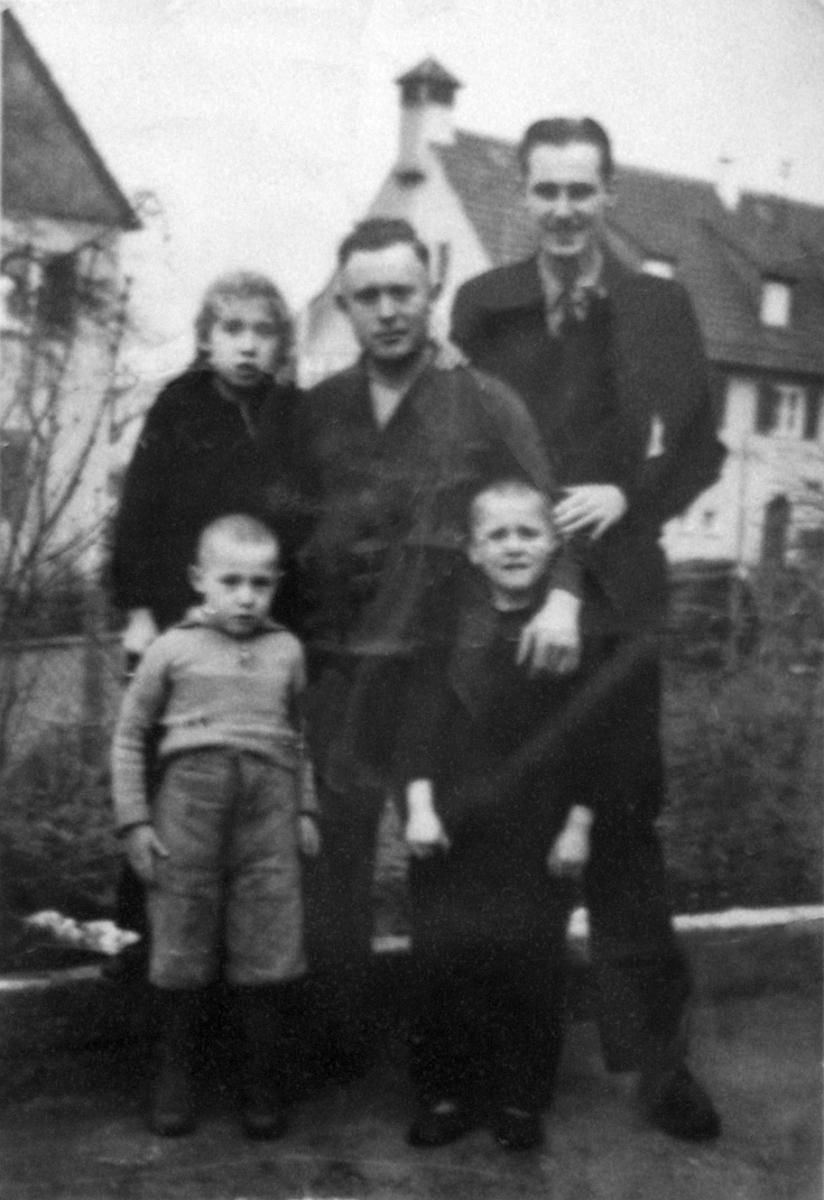

Fig. 2. The Rügner family and other members of the Feuerbach Branch. (R. Rügner)

Fig. 2. The Rügner family and other members of the Feuerbach Branch. (R. Rügner)

The Rügner family apartment was destroyed in an air raid in January 1945, and the family lost most of their property. All that remained were the things they had carried into the shelter and some items that had been stored in the basement. Reinhold was allowed to leave school for a few weeks to assist his father in the cleanup. About that time, the branch meeting rooms were damaged, but the broken windows were covered up, and life went on.

Fig. 3. The Primary organization of the Feuerbach Branch. (R. Rügner)

Fig. 3. The Primary organization of the Feuerbach Branch. (R. Rügner)

Reinhold recalled losing his brother Werner in the last year of the war: “He told us right before he left that he really did not want to leave [for war] anymore. My brother died in an airplane accident on June 6, 1944, in Czechoslovakia. He had been on leave until June 1 and had just reported back for duty. A telegram with the message of his death was handed to us by a city official.”

Reinhold was sent home from the Nürtingen school in April 1945 and arrived in time to see the French invaders arrive. He told this story:

To be honest, we had great respect for the French. It was a scary time. Many of the French soldiers had dark skin because they came from Morocco. That was the first time that I saw dark-skinned people. I knew that they existed, but it was a good experience to finally meet an African person. Often, they acted very uncivilized and would steal the chickens and rabbits that we raised for food. We also had a curfew and were not allowed to leave the house after four or five p.m.

Life under military occupation was an insecure existence at best. Gottlob Rügner once stood between his daughter and French soldiers with evil intent who threatened to shoot the branch president. He stood his ground, and the soldiers left. On another occasion, Reinhold and a sister climbed out of their window after curfew and ran two blocks to a house where a French officer was quartered to report soldiers threatening their family. The officer returned with them, “raised his gun, and walked into our home. He escorted the soldiers out just in the nick of time.”

Fig. 4. Family members of Reinhold Rügner. (R. Rügner)

Fig. 4. Family members of Reinhold Rügner. (R. Rügner)

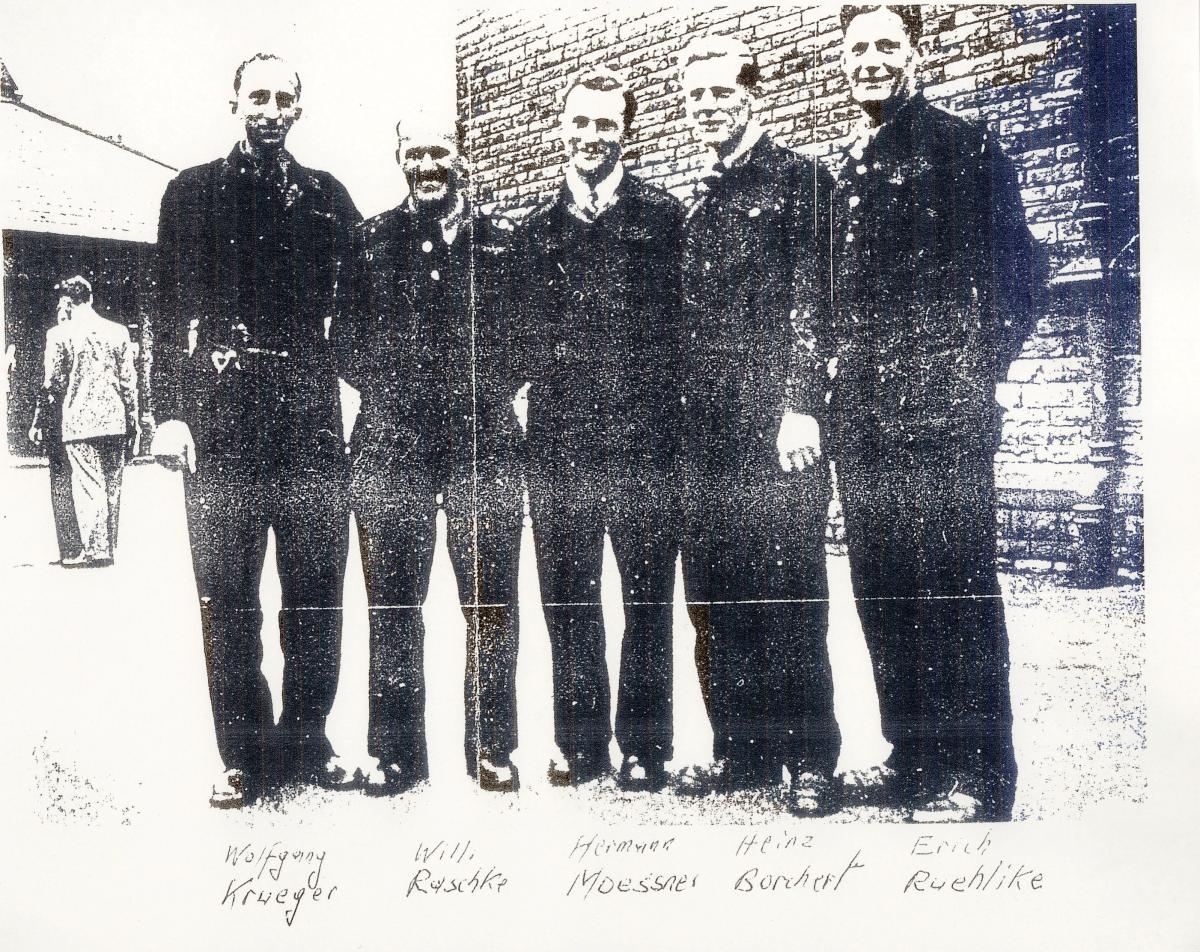

As a POW in England, Hermann Mössner was a very successful missionary for the Church. He told this story:

I was the only Latter-day Saint [among the German POWs]. I taught the other soldiers who shared a room with me and they were ready to get baptized when it was time for us to go home. The baptism took place while we were still prisoners. The British Latter-day Saints came and picked us up and the entire camp noticed it. The Catholic priest, who was also a German, started to complain to the commandant of the camp. I was then invited to the office of the British major, and next to him stood a representative of the Church of England. He was the only one who spoke to me and it was not in a nice tone of voice. He asked me, “By what authority to do baptize your fellow prisoners?” He screamed that question. I, in contrast, answered him with a calm voice that we did it with the authority of the priesthood (I had been ordained an elder in 1943). He then yelled at me to get out of the room. By the end of the time in the camp, there were five of us members of the Church. They went home and even converted their families. I also carried my scriptures with me—even in the most dangerous situations at the front. I was so blessed through that. I lost my scriptures, which were given to me by my grandfather, when I was at the front one day. But when I was in England, I wrote a letter to the mission office in London, and they sent me Church literature to read.

Brother Mössner was allowed to conduct the baptisms of his friends in the Bradford/

The officers in the camp did not allow us to hold meetings in the chapel that was available. But I wrote to Salt Lake City and complained that we wanted a place to meet. Just a short time later, I was again asked to go into the commandant’s office. He then allowed us to hold meetings in the chapel. Gordon B. Hinckley was the one who received my postcard and wrote a letter to the camp in which we were held. We conducted our meetings but we did not have the sacrament during that time. We also had some investigators who attended our meetings. We were also allowed to leave the camp on Sundays, so six or more German prisoners of war walked to Leeds City to find a branch to attend. People spit at us and laughed. The branch in Leeds was so welcoming, and they were happy to have us. [6]

Fig. 5. Hermann Mössner, a German elder and the men he introduced to the gospel (from left): Wolfgang Krüger, Willi Raschke, Hermann Mössner, Heinz Borchert, Erich Rühlike. (H. Mössner)

Fig. 5. Hermann Mössner, a German elder and the men he introduced to the gospel (from left): Wolfgang Krüger, Willi Raschke, Hermann Mössner, Heinz Borchert, Erich Rühlike. (H. Mössner)

During his incarceration, Hermann was called to the camp office one day and introduced to Hugh B. Brown, then the president of the British Mission. President Brown had been conducting a district conference nearby and had heard of this young German Latter-day Saint. Hermann was moved by the compassion of that great leader. [7]

Hermann Mössner’s remarkable story of religious dedication among German POWs had a happy ending:

I was sent home in May 1948. My son was already three years old, and it was the first time that I was able to see him. Coming home was the most wonderful day of my life. The train stopped in the station, and the authorities told us that we had to wait until we were released the next day. We thought that because the train was already at its final destination, we would be able to walk those few miles home. That is what we did. The next morning, I walked back to the train and we were released. Everybody was so surprised to see me again. [8]

The Feuerbach Branch had suffered significant losses in families, homes, and property, but the survivors continued to hold meetings and regrouped in the summer of 1945. In retrospect, Hermann observed:

The accounts of distress of individual families whose fathers and sons had fallen at the war front, and the losses among the members due to air raids were painful; yet it was the faith in our God and the firm hope of eternal life that gave us the strength to carry on and continue. [9]

In Memoriam

The following members of the Feuerbach Branch did not survive World War II:

Emil Buck b. Stuttgart, Feuerbach, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 13 Jul 1912; son of Johannes Buck and Sophie Löffler; bp. 11 Apr 1924; conf. 11 Apr 1924; corporal; d. H.V. Pl. Melnitschny/

Frieda Patzsch Lehmann b. Triberg, Villingen, Baden, 16 Dec 1891; dau. of Lukas Lehmann and Kandide Schweer; bp. 30 May 1931; conf. 30 May 1931; m. Hermann Louis Patzsch; m. 18 Dec 1938, Gottfried Horrlacher; d. sickness 20 Sep or Oct 1939 (FHL microfilm 68790, no. 39; CHL CR 375 8, 2451, no. 499; IGI)

Hildegard Mössner b. Feuerbach, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 13 Jan 1918; dau. of Karl Mössner and Rosine Wilhelmine Schönhardt; bp. 22 May 1927; conf. 22 May 1927; d. hemoptysis and tuberculosis 10 Feb 1940 (FHL microfilm 68790, no. 15; IGI; FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 402; CHL CR 375 8, 2451, no. 402; FHL microfilm 245238; 1930 and 1935 censuses)

Karl Mössner, Jr. b. Feuerbach, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 11 Dec 1912; son of Karl Mössnerk Sr. and Rosine Wilhelmine Schönhardt; bp. 10 Feb 1924; conf. 10 Feb 1924; ord. deacon 15 Apr 1928; ord. teacher 23 Aug 1931; ord. priest 9 Feb 1938; ord. elder 25 Apr 1937, Swiss-German Mission; m. 15 Feb 1936, Else Kübler (div.); m. 29 Oct 1938, Olga Poers or Evers; rifleman; k. in battle near Karoli, Belarus, 18 Jul 1941 (FHL microfilm 68790, no. 13; www.volksbund.de; FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 860; CHL CR 375 8, 2451, no. 860; IGI; AF)

Esther Rügner b. Feuerbach, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 20 Apr 1919; dau. of Gottlob Rügner and Lina Dorothea Schonhardt; bp. 6 Jun 1928; conf. 6 Jun 1928; m. Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 5 Feb 1938, Herbert Helmrich; d. Typhoid, Bad Diersdorf, Eulengeb., Sil., Preußen, 9 or 10 September 1935 (FamilySearch; Reinhold Rügner)

Werner Friedrich Rügner b. Stuttgart, Neckarkreis, Württemberg, 12 Jan 1923; son of Gottlob Rügner and Lina Dorothea Schönhardt; bp. 25 Jan 1931; conf. 25 Jan 1931; ord. deacon 20 Jun 1937; ord. teacher 2 Mar 1941; ord. priest 30 Mar or May 1944; lance corporal; k. airplane accident Wobora, 6 Jun 1944; bur. Plzen, Czechoslovakia (FHL microfilm 68790, no. 24; FHL microfilm 68807, book 1, no. 434; FHL microfilm no. 271407; 1930 and 1935 censuses; www.volksbund.de; IGI; AF)

Fig. 6. Werner Rügner as a Hitler Youth and as a soldier of the Luftwaffe. (R. Rügner)

Fig. 6. Werner Rügner as a Hitler Youth and as a soldier of the Luftwaffe. (R. Rügner)

Karoline Friederike Bauer b. Neuenhaus, Nürtingen, Schwarzwaldkreis, Württemberg, 1 Nov 1887; dau. of Ernst Ludwig Bauer and Marie Katharine Schlecht; bp. 27 Sep 1928; conf. 27 Sep 1928; m. Ludwigsburg, Ludwigsburg, Württemberg, 14 Jan 1912 or 1913, Adolf Peukert; d. peritonitis, 11 Nov 1940 (FHL microfilm 68807, book 2, no. 325; FHL microfilm 245254; 1930 and 1935 censuses; IGI)

Notes

[1] Reinhold Rügner, interview by Michael Corley, Salt Lake City, December 5, 2008.

[2] Hermann Mössner, interview by Jennifer Heckmann in German, Stuttgart, Germany, August 23, 2007; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[3] West German Mission branch directory, 1939, CHL LR 10045 11.

[4] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” 257, CHL CR 4 12.

[5] Hermann Mössner, “Mormon Pioneers in Southern Germany” (unpublished manuscript).

[6] Mössner, interview.

[7] Mössner, “Mormon Pioneers.”

[8] Mössner, interview.

[9] Mössner, “Mormon Pioneers.”